On-demand manipulation of protein release to alter cellular phenotypes in real time is of great interest to the fields of drug delivery, tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.[1-3] For such therapeutic and research ventures, hydrogels, due to their high water content and mechanical stability, have emerged as suitable polymeric materials not only to localize proteins but also to control their release rate on-site.[4, 5] Protein release from hydrogels is typically achieved either through diffusion or by stimuli. Diffusion controlled mechanisms rely upon control of the hydrogel mesh size, which needs to be preprogrammed during synthesis; as a result, limited regulation of release is only possible afterward. To complement this strategy, stimuli (e.g., temperature, pH, light and proteins)[6, 7] sensitive materials have evolved and become attractive protein delivery systems, as they offer opportunities to regulate molecular release using a specific stimulus. Stimuli controlled mechanisms applied to hydrogels are typically based on the degradation/swelling of hydrogel networks, in which non-covalently sequestered proteins are released in response to increased pore size/decrosslinking of networks. Such noncovalent approaches do not require chemical modification of proteins and have the potential to precisely control the release of single protein molecules. However, applying such approaches to control the release of multiple proteins is quite complex and often requires either multiple gels or microspheres for encapsulation.[8-12] Thus, a number of studies aimed at directing cellular processes or disease regulation would benefit from the delivery of more than one protein and often necessitates their delivery in varied doses at different time points [8-11]. Herein, we present an approach that allows precise control over the release of multiple proteins from a single hydrogel depot using an external light.

Light triggered molecular cleavage has received widespread interest among researchers in recent years, for activation of caged biomolecular entities,[13-15] alteration of material properties,[16, 17] and to control therapeutic release in real-time.[18, 19] Furthermore, user-defined time and spatial location of photocleavage reactions offer unique opportunities to control material properties more precisely than other classical stimuli.[14] However, many of these approaches rely on a single photocleavable unit, and thus, provide limited opportunities to control different material properties independently. To date, specific examples of wavelength selective molecular activation by orthogonally functional units were introduced into the literature by Bochet,[20] and are now emerging as powerful strategies in controlling different properties in a sequential manner. Towards this, del Campo et al. first demonstrated utility of such wavelength selective photocleavable concepts by the spatial immobilization of multiple particles/fluorophores;[21] where they initially utilized 3,5-dimethoxy benzoin esters and nitrobenzyl derivatives,[21] a combination of functionalities coined by Bochet as orthogonal units. Later nitrobenzyl and coumarin derivatives have been subsequently explored as a new combination of orthogonal units,[22] which have been widely exploited for sequential uncaging of bioactive units for orderly regulation of biological actions.[23-27] More recently, sequential photoactivation of biomolecular ligands for spatio-temporal patterning of multiple proteins in a 3D gel matrix has also been reported.[28-30] In this contribution, we present two distinctive photocleavable units, based on: (i) nitrobenzyl ether (NB) and (ii) coumarin methylester (CM), that can be selectively cleaved at different wavelengths of light and then harness their wavelength dependent photodegradable characteristics to regulate the release of multiple proteins at different time points. Specifically, proteins were covalently conjugated to hydrogel networks via photodegradable units[31-34] and the control over their release was achieved by simply varying the wavelength of light, intensity and time of light exposure.

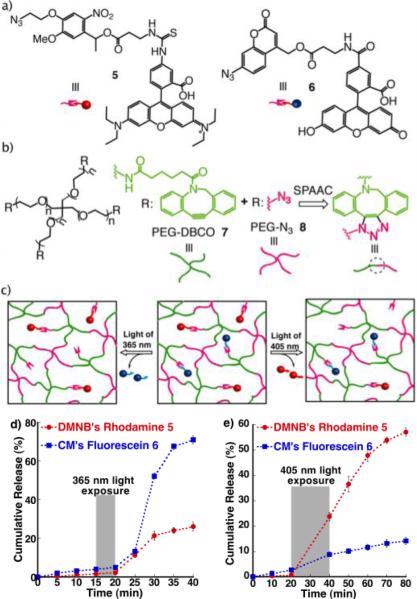

The molecular structures of NB, 1 and CM, 2 (See SI for syntheses of 1 and 2) utilized in this work are shown in Figure 1a. Note that both 1 and 2 possess an azide functionality for subsequent functionalization of these molecules using click chemistry, and furthermore, the azide functionality of the coumarin molecule 2 utilized in this study is conjugated to the core ring structure. Under irradiation with UV/Visible light, nitrobenzyl derivatives, such as 1 cleave to produce nitrosoacetophenone 3 as a byproduct,[16] while the coumarin methylester yields the corresponding coumarin methanol 4.[35, 36] Prior to utilizing these molecules for protein release, we first studied the photodegradation kinetics of 1 and 2 (2.5 mM) by separately exposing them to both 365 nm (10mW/cm2) and 405 nm (10mW/cm2), and analyzing the exposed solutions of 1 and 2 by reverse-phase HPLC. Before exposing to light, both 1 and 2 exhibited single peaks in the chromatogram, but exposure to 365 and 405 nm light resulted in the formation of distinguishable new peaks corresponding to the degraded products 3 and 4 (See SI for HPLC chromatograms). The relative photodegradation of 1 and 2 at different times of exposure to 365 nm light is shown in Figure 1b, in which CM 2 exhibited a very high degradation rate as compared to its nitrobenzyl counter part 1. The kinetic constant of degradation (k), determined from the slope of semi-logarithmic plot of Figure 1b (Table 1) (See SI for calculation details and corresponding semi-logarithmic plots), showed that k of 2 was four times higher than that of 1 at 365 nm. Conversely, to our surprise, when exposed to 405 nm (Figure 1c), the degradation trend reversed, where 1 exhibited efficient degradation and its k was found to be an order of magnitude higher than that of 2 (Table 1). The results clearly suggested that 1 and 2 undergo wavelength selective cleavage, i.e., at 365 nm light, 2 degrades faster than 1 and vice versa at 405 nm. To better understand these differences, we calculated the molar extinction coefficient at the degrading wavelength (ε) of 1 and 2 and their quantum yield of degradation (φ) (Table 1 and Figure 1d), as these parameters directly correlate with k [17]. Even though the molar extinction coefficient of 1 at 365 nm is twice as high as 2, we expect that the enhanced degradation of 2 at 365 nm is likely due to its higher quantum yield of degradation (φ). At the same time, almost an order of magnitude lower ε of 2 over 1 at longer wavelengths (i.e., at 405 nm) drastically decreases its degradation kinetics and ascribed the relative higher degradation kinetics of 1 over 2 at 405 nm. In summary, it appears that both quantum yield of degradation and molar extinction coefficient play critical roles in the degradation behaviours of 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Wavelength dependent orthogonal photodegradation: a) Photocleavage of nitrobenzyl (NB) and coumarin methylester (CM) molecular systems: 1 and 2 and their corresponding photocleaved products 3 and 4; Comparative photodegradation of 1 and 2 at (b) 365 nm and (c) 405 nm for different times of light exposure. d) Absorbance spectra of 1 (0.4 mM) and 2 (0.4 mM) dissolved in acetonitrile/PBS mixture (8:2).

Table 1.

Degradation kinetic constant (k), molar extinction coefficient (ε) and quantum yield of degradation (φ). (for error limits see SI)

| Units | k365 × 10−3/s | k405 × 10−3/s | ε365 cm−1M−1 | ε405 cm−1M−1 | φ 365 | φ 405 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NB 1 | 4 | 2 | 4437 | 935 | 0.16 | 0.11 |

| CM 2 | 13 | 0.7 | 2183 | 150 | 0.57 | 0.15 |

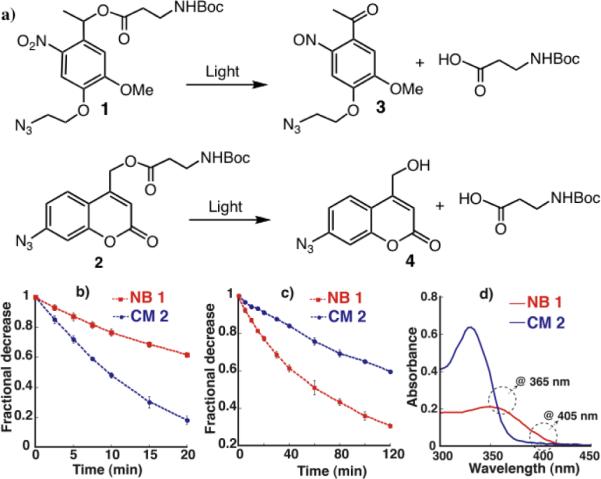

We next explored the utility of photodegradable units 1 and 2 for selective, light controlled release of model compounds; for which we first utilized small molecular weight dyes. Rhodamine B isothiocyanate and fluorescein N-hydroxysuccinimidyl ester were conjugated to nitrobenzyl azide 1 and coumarin azide 2, respectively, to afford the corresponding rhodamine tethered nitrobenzyl azide 5 and fluorescein tethered coumarin azide 6 (Figure 2a). The dye conjugated photodegradable azides 5 and 6 were then covalently bound into poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels via copper-free, strain-promoted azidealkyne click (SPAAC);[37] this hydrogel formulation was selected as it does not require any additional reagents or initiators that might lessen bioactivity of proteins during encapsulation. 4-armed PEG tetradibenzocyclooctyne (PEG-DBCO) 7 and 4-armed PEG tetraazide (PEG-N3) 8 were used as precursors to form the hydrogel (Figure 2b). In this case, a slight molar excess of PEG-DBCO 7 over PEG-N3 8 was used in order to allow subsequent covalent tethering of azides 5 and 6.

Figure 2.

(a) Chemical structures of rhodamine B tethered nitrobenzyl azide 5 and fluorescein tethered coumarin azide 6; (b) PEG polymeric precursors that produce SPACC hydrogel networks: 4-arm PEG-tetra DBCO 7 and 4-arm PEG-tetraazide 8; (c) Schematic representation of light-wavelength regulated selective release of dye molecules from hydrogel networks; Dye release studies upon exposure to light sources of (d) 365 nm (10 mW/cm2) for 5 mins and (e) 405 nm (10 mW/cm2) for 20 mins. Gray bars indicate the light exposure.

We first tested the light triggered release capabilities of 5 and 6 by separately incorporating them into different hydrogels and exposing to 365 nm light (10 mW/cm2) for 10 minutes. A sudden increase in fluorescence observed within 10 minutes in both cases clearly indicated the release of covalently tethered dye molecules into solution. Then, to investigate orthogonal release, both 5 and 6 were together introduced at equal concentrations into a single hydrogel depot and exposed to both 365 and 405 nm light sources separately (Figure 2c). After 5 minutes of irradiation with 10 mW/cm2 of 365 nm light (Figure 2d), almost 70% of coumarin's fluorescein was observed to be released from the gel in a period of just 20 minutes after exposure, while the release of nitrobenzyl's rhodamine was only about 26%, presumably due to the enhanced cleavage rate of coumarin methyl esters over nitrobenzyl ethers. However, under the same conditions, when gels were exposed to 10 mW/cm2 of 405 nm for 20 minutes (Figure 2e), the release of rhodamine (60%) was significantly higher than that of fluorescein (10%), indicating not only an inversion in the cleavage trend, but also the higher photocleavage rate of nitrobenzyl over coumarin at 405 nm. Two points are noteworthy here: (i) The dye release trend is in agreement with the cleavage data quantified in solution, photocleavage studies of 1 and 2 (Figure 1) (ii) Conversion of the conjugated azide of coumarin 2 into its corresponding triazole did not result in significant change in its degradation behaviour. Overall, these results demonstrated the feasibility for the photocleavable units 1 and 2 as orthogonal units to independently control the release of dual therapeutic agents post gel formation.

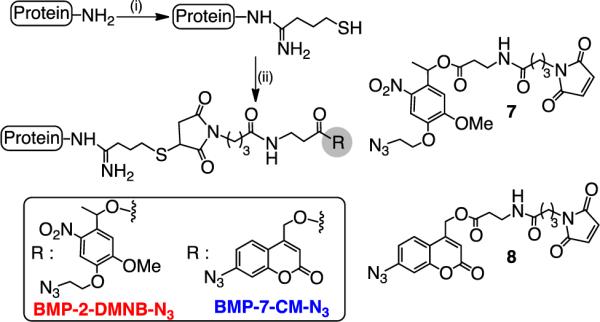

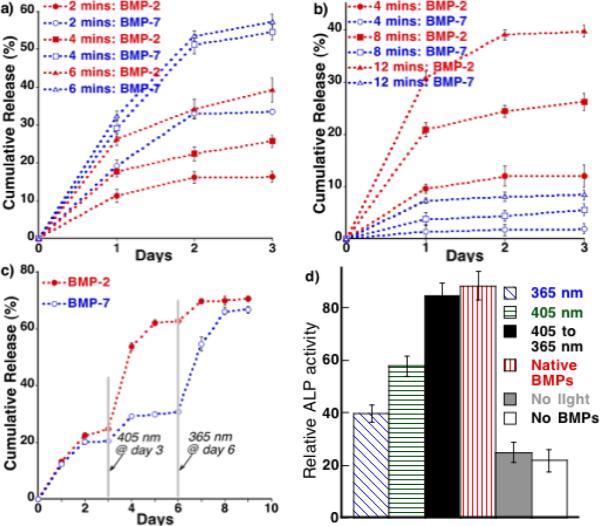

The orthogonal dye release results then prompted us to further investigate the effectiveness of 1 and 2 in regulating the release of two different proteins of biological relevance. For this purpose, we selected isoforms of the bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs): BMP-2 and BMP-7, which are key regulatory proteins closely involved in the cascade of events occur during bone regeneration. Further, recent studies have shown that delivering BMP-2 and -7 in combination or in a sequential manner results in improved osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs).[10, 38] Here, BMPs were covalently modified with photocleavable azides to enable their attachment to SPACC hydrogels and later to trigger their release upon exposure to light of pre-selected wavelengths. BMP modification was achieved upon treating the amine functionality of the proteins with Traut's reagent to produce an extended free thiol and then exposing the resultant thiol to maleimide containing photocleavable azides 7 and 8 (Scheme 1). The resulting modified proteins BMP-2-NB-N3 (5 ng) and BMP-7-CM-N3 (5 ng) were then altogether introduced into the hydrogel via SPAAC (Figure 3a). After leaching out untethered protein molecules for 3 days, the hydrogels were separately exposed to light of 365 (5 mW/cm2) and 405 nm (5 mW/cm2) at day 4, and analyzed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to monitor the BMP release kinetics. In hydrogels exposed to 365 nm light for either 2, 4 or 6 minutes independently (Figure 3a), we observed significantly increased release of BMP-7, i.e., tethered via coumarin, over nitrobenzyl tethered BMP-2. As expected, the amount of protein release increased steadily with increasing light exposure, but in case of BMP-7, the trend continued only up to 4 minutes. No significant increase in cumulative release was observed upon further light exposure, suggesting that optimal light exposures can be tailored to achieve maximum release of BMP-7 while minimizing BMP-2 release. At the same time, release data obtained for hydrogels exposed to 405 nm light for various times (Figure 3b) led to the expected opposite trend with increased BMP-2 release compared to BMP-7 (as observed with the model compound release studies, Figure 2d and e).

Scheme 1.

Incorporation of photocleavable azides onto BMP-2 and BMP-7 proteins respectively: (i) Traut's reagent, pH: 7.0, Phosphate buffer (PBS), rt; (ii) 7 (for BMP-2) or 8 (for BMP-7), PBS, pH: 7.0, rt.

Figure 3.

Daily release of BMP-2 and BMP-7 upon exposure to light of (a) 365 nm (5 mW/cm2) and (b) 405 nm (5 mW/cm2) for varied times; (c) Sequential release of BMP-2 and BMP-7 upon exposing to both 405 and 365 nm light but at different time points; d) Relative ALP activity for hMSCs seeded on hydrogels that covalently contained both BMP-2 and BMP-7 in equal amounts (10ng/ml) and exposed to 365 nm (for 6 mins) and 405 nm (for 12 mins) separately and also to both but sequentially, i.e., 405 first for 12 mins and then 365 for 6 mins (405 to 365 nm, 5mW/cm2); native BMPS: cells seeded on PEG hydrogels and exposed to BMP-2 and BMP-7 (10ng/ml) but at day 1 and day 4 respectively; no light: not exposed to any light but gel covalently contained both BMPs; no BMPs: cells seeded on hydrogel that did not contain any proteins.

We then sought to investigate the possibility of releasing both proteins from a single gel, but in a manner that allowed their sequential and independent release. To achieve this, hydrogels were first exposed to 405 nm for 12 min at day 3, which resulted in a substantial and predominant release of BMP-2, and then exposed to 365 nm for 6 min at day 6 to trigger the release of the still tethered BMP-7. Figure 3c shows the entire daily release of both the proteins starting from before and after exposing to light of 405 and 365 nm to trigger their cleavage and release from the gel. This result clearly illustrates that the second exposure to 365 nm light results in extensive release of BMP-7 (~ 40%), suggesting the requisite of higher energy light for cleavage of coumarin molecules and the resulting release of tethered BMP-7. Given that the majority of the BMP-2 (~62%) was released during the first exposure to 405 nm light, the second exposure at 365 nm resulted in just 10% release of additional BMP-2. Taken together, the amount of recovered BMP-2 and BMP-7 was in the range of ~68-72%. Overall, the release results clearly demonstrated the sequential release of BMP-2 and BMP-7 by an orderly exposure to light of different wavelengths.

Next, we tested the bioactivity of released BMPs by evaluating their influence on osteogenic differentiation of human MSCs (hMSCs), as measured by their alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity at day 8. First, we observed that (i) neither light exposure nor covalent modification of the BMPs significantly affected their bioactivity, ii) hMSCs exposed to photoreleased BMP-2 and BMP-7 led to elevated levels of ALP compared to control cells that were not exposed to either BMPs, and iii) BMP-2 appeared to influence ALP activity more as compared to BMP-7 (SI). Then, to test the activity of sequential release of BMPs, BMP-2 and BMP-7 were first separately conjugated into different hydrogel formulations, and hMSCs were seeded on top of the gel. After allowing the cells to adhere to the gel surface, the gels were exposed to 365nm light (5mW/cm2) for 10 minutes. When analyzed at day 8 (see Figure S4 in SI), hMSC ALP activity was increased for photoreleased gels, as compared to controls (i.e., not exposed to light), but it was also comparable to the cellular responses obtained for native BMPs delivered in a soluble form. These results suggest that BMPs released by light indeed retain a bioactive nature that can locally influence cellular function.

Finally, to test the ability to sequentially deliver proteins, the impact of sequential release of BMP-2 and BMP-7 was tested by first seeding hMSCs on gel that covalently contained both growth factors. The cell-laden gels were first exposed to 405 nm light for 12 minutes at day 1, and after allowing the hMSCs to interact with the first protein, BMP-2, for three days, we again exposed the gel to 365 nm light for 6 minutes at day 4 to trigger the release of the second protein, BMP-7. These cellular responses were analysed at day 8 (Figure 3d) and show that: (i) ALP activity in hMSCs exposed to both 405 and 365 nm, but in a sequential manner, was greater than that of cells exposed to only 405 nm, which largely releases BMP-2 or 365 nm light, which mostly trigger the release of BMP-7; (ii) the cellular activity observed during sequential exposure was comparable to that exposed to native BMP-2 and BMP-7 at day 1 and day 4, respectively. Collectively, these results clearly suggested that differentiation of hMSCs can be manipulated by sequential release of BMP-2 then BMP-7 by user defined exposure to 405 and 365 nm light.

In summary, we have synthesized and studied a new combination of selectively photocleavable nitrobenzyl and coumarin based molecular entities using light of different wavelengths. Our study has shown that the coumarin azides 2 cleave better than nitrobenzyls 1 with 365 nm light, but the cleavage of nitrobenzyl 1 is more efficient than coumarin 2 at 405 nm. We demonstrated the potential utility of the wavelength dependent photocleavable characteristics of these molecular units to selectively release dye/protein (BMP-2 and -7) molecules of any choice from a single hydrogel depot post-gel formation. Selective protein release was further leveraged to stimulate sequential signalling of hMSCs at different time points by systematically switching the light from one wavelength to another. Such orthogonally programmed multiple protein release should allow researchers to tune the release kinetics of multiple proteins at any point of time from pre-loaded protein depots. We expect that this work should provide basic insight for strategies to synthesize and engineer new materials for controlled delivery of more than one protein with various release patterns and profiles and ultimately have implications in approaches to design materials for applications in the delivery of protein therapeutics as related to tissue regeneration, wound healing, and disease treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the National Science Foundation (DM 1006711) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute for funding. We would also like to thank Dr. Daniel Alge for discussion.

References

- 1.Peppas NA, Langer R. Science. 1994;263:1715. doi: 10.1126/science.8134835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Putney SD, Burke PA. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998;16:153. doi: 10.1038/nbt0298-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee KY, Peters MC, Anderson KW, Mooney DJ. Nature. 2000;408:998. doi: 10.1038/35050141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin SP, Saltzman WM. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 1998;33:71. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(98)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Censi R, Di Martino P, Vermonden T, Hennink WE. J. Controlled Release. 2012;161:680. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murthy N, Xu MC, Schuck S, Kunisawa J, Shastri N, Frechet JMJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:4995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0930644100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azagarsamy MA, Sokkalingam P, Thayumanavan S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:14184. doi: 10.1021/ja906162u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richardson TP, Peters MC, Ennett AB, Mooney DJ. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:1029. doi: 10.1038/nbt1101-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sohier J, Vlugt TJH, Cabrol N, Van Blitterswijk C, de Groot K, Bezemer JM. J. Controlled Release. 2006;111:95. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basmanav FB, Kose GT, Hasirci V. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4195. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen FM, Zhang M, Wu ZF. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6279. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffin DR, Kasko AM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:13103. doi: 10.1021/ja305280w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen S, Alonso JM, Specht A, Duodu P, Goeldner M, del Campo A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:3192. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brieke C, Rohrbach F, Gottschalk A, Mayer G, Heckel A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:8446. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui JX, San Miguel V, del Campo A. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2013;34:310. doi: 10.1002/marc.201200634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kloxin AM, Kasko AM, Salinas CN, Anseth KS. Science. 2009;324:59. doi: 10.1126/science.1169494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeForest CA, Anseth KS. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:925. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HI, Wu W, Oh JK, Mueller L, Sherwood G, Peteanu L, Kowalewski T, Matyjaszewski K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:2453. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan B, Boyer JC, Habault D, Branda NR, Zhao Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:16558. doi: 10.1021/ja308876j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bochet CG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:2071. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2071::AID-ANIE2071>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.del Campo A, Boos D, Spiess HW, Jonas U. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:4707. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stegmaier P, Alonso JM, del Campo A. Langmuir. 2008;24:11872. doi: 10.1021/la802052u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotzur N, Briand B, Beyermann M, Hagen V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:16927. doi: 10.1021/ja907287n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kantevari S, Matsuzaki M, Kanemoto Y, Kasai H, Ellis-Davies GCR. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:123. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.San Miguel V, Bochet CG, del Campo A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:5380. doi: 10.1021/ja110572j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goguen BN, Aemissegger A, Imperiali B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:11038. doi: 10.1021/ja2028074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fomina N, McFearin CL, Sermsakdi M, Morachis JM, Almutairi A. Macromolecules. 2011;44:8590. doi: 10.1021/ma201850q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gatterdam V, Stoess T, Menge C, Heckel A, Tampe R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:3960. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laboria N, Wieneke R, Tampe R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:848. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grunwald C, Schulze K, Reichel A, Weiss VU, Blaas D, Piehler J, Wiesmuller KH, Tampe R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:6146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912617107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakayama K, Tachikawa T, Majima T. Langmuir. 2008;24:6425. doi: 10.1021/la801028m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alonso JM, Reichel A, Piehler J, del Campo A. Langmuir. 2008;24:448. doi: 10.1021/la702696b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wirkner M, Alonso JM, Maus V, Salierno M, Lee TT, Garcia AJ, del Campo A. Adv. Mater. 2011;23:3907. doi: 10.1002/adma.201100925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvarez M, Alonso JM, Filevich O, Bhagawati M, Etchenique R, Piehler J, del Campo A. Langmuir. 2011;27:2789. doi: 10.1021/la104511x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao YR, Zheng Q, Dakin K, Xu K, Martinez ML, Li WH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:4653. doi: 10.1021/ja036958m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Babin J, Pelletier M, Lepage M, Allard JF, Morris D, Zhao Y. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:3329. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeForest CA, Polizzotti BD, Anseth KS. Nat. Mater. 2009;8:659. doi: 10.1038/nmat2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu HW, Chen CH, Tsai CL, Lin IH, Hsiue GH. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:1113. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.