Abstract

Background

Because of uncertainty regarding the reliability of perioperative blood pressures and traditional notions downplaying the role of anesthesiologists in longitudinal patient care, there is no consensus for anesthesiologists to recommend postoperative primary care blood pressure follow-up for patients presenting for surgery with an elevated blood pressure. The decision of whom to refer should ideally be based on a predictive model that balances performance with ease-of-use. If an acceptable decision-rule were developed, a new practice paradigm integrating the surgical encounter into broader public health efforts could be tested, with the goal of reducing long-term morbidity from hypertension among surgical patients.

Methods

Using national data from United States veterans receiving surgical care, we determined the prevalence of poorly controlled outpatient clinic blood pressures ≥ 140/90mmHg, based on the mean of up to four readings in the year after surgery. Four increasingly complex logistic regression models were assessed to predict this outcome. The first included the mean of two preoperative blood pressure readings; other models progressively added a broad array of demographic and clinical data. After internal validation, the C-statistics and the Net Reclassification Index between the simplest and most complex models were assessed. The performance characteristics of several simple blood pressure referral thresholds were then calculated.

Results

Among 215,621 patients, poorly controlled outpatient clinic blood pressure was present postoperatively in 25.7% (95%CI 25.5%-25.9%) including 14.2% (95%CI 13.9%-14.6%) of patients lacking a prior hypertension history. The most complex prediction model demonstrated statistically significant, but clinically marginal, improvement in discrimination over a model based on preoperative blood pressure alone (C-statistic 0.736 (95% CI 0.734-0.739) vs 0.721 (95% CI 0.718-0.723); p for difference <0.0001). The Net Reclassification Index was 0.088 (95%CI 0.082-0.093), p < 0.0001. A preoperative blood pressure threshold ≥ 150/95mmHg, calculated as the mean of two readings, identified patients more likely than not to demonstrate outpatient clinic blood pressures in the hypertensive range. Four of five patients not meeting this criterion were indeed found to be normotensive during outpatient clinic follow-up (Positive Predictive Value 51.5%, 95% CI 51.0-52.0; Negative Predictive Value 79.6%, 95% CI 79.4-79.7).

Conclusions

In a national cohort of surgical patients, poorly controlled postoperative clinic blood pressure was present in more than 1 of 4 patients (95%CI 25.5%-25.9%). Predictive modeling based on the mean of two preoperative blood pressure measurements performed nearly as well as more complicated models and may provide acceptable predictive performance to guide postoperative referral decisions. Future studies of the feasibility and efficacy of such referrals are needed to assess possible beneficial effects on long-term cardiovascular morbidity.

Introduction

Uncontrolled blood pressure confers an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality in both men and women and across a broad range of ages and ethnicities.1-6 The longitudinal use of medications to lower blood pressure reduces the risk of cardiovascular morbidity7-9 and is associated with a reduction in the lifetime risk of incident cardiovascular disease.10 Despite such well-established evidence for the long-term benefits of lowering blood pressure, 22% of United States adults are unaware of having elevated blood pressure and 32% of those prescribed blood pressure lowering medication are not taking them as prescribed.11 Among patients with uncontrolled blood pressure in the United States, 89.4% report that they have a usual source of health care.12 Thus, factors other than access to care must in part contribute to the problem of chronically elevated blood pressure.

The American Heart Association has advocated that the perioperative period provides an important opportunity to screen for poorly controlled blood pressure and/or undiagnosed hypertension.13 Yet, while widely accepted guidelines are available to primary care providers for the identification and management of elevated blood pressure,14,15 no such guidelines are available to inform anesthesia providers regarding blood pressure thresholds that should trigger postoperative referral of surgical patients for primary care blood pressure management. Numerous factors may acutely affect blood pressure preoperatively,16 leading to doubt among anesthesiologists about which patients are truly in need of referral. Among the factors that are commonly invoked against the diagnostic value of preoperative blood pressures for determining the need for referral are 1) perioperative dehydration from fasting or bowel regimens,17 2) psychological stress,18,19 and 3) short-term preoperative medication changes or medication non-adherence.20-23 These sources of uncertainty, as well as doubts about the proper role of anesthesiologists in longitudinal outpatient care, may cause anesthesiologists to miss a valuable opportunity to promote better postoperative blood pressure management, and thereby improve public health. In our prior work, we used records from a single institution to identify blood pressure thresholds that achieved 95% specificity for the outcome of postoperative elevated blood pressure in patients presenting for surgery from home, but these findings were limited by the use of a single center, the exclusion of hospital inpatients, and the reliance on a single postoperative blood pressure reading to determine the outcome of elevated clinic blood pressure.16 Moreover, although we and other investigators18,20,23 have studied changes in blood pressure between surgical and other medical settings, none, to our knowledge, has specifically attempted to compare increasingly complex perioperative prediction models with the goal to balance model complexity and ease-of-use in identifying patients with elevated postoperative clinic blood pressures.

Accordingly, the purpose of the present study was to contribute to the evidentiary foundations for anesthesiologist-led blood pressure referral by, a) describing the prevalence of poorly controlled clinic blood pressure among a large national cohort of surgical patients and, b) evaluating and comparing increasingly complex models that use perioperative blood pressure along with a broad array of other clinical and demographic data to identify surgical patients who are likely to have elevated clinic blood pressures in the year after surgery. To the extent that such a model can demonstrate a balance of adequate predictive performance and clinical usability, it may be a useful tool to help providers decide which patients ought to be referred to a primary care provider for postsurgical blood pressure management.24 In pursuit of these aims, we analyzed electronic health record (EHR) data of veterans who received surgical care from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VHA), the largest single healthcare system in the United States, with over 8.3 million enrollees as of 2010.25

Methods

With IRB approval including a waiver of the requirement for informed consent, we created an EHR-based historical cohort of patients age ≥ 21 years who received surgical care at any VHA healthcare facility between Sept 1, 2006 and Aug 31, 2011, inclusively. The VHA Corporate Data Warehouse national surgeries extract was used for cohort identification. Patients were identified by their unique Patient Integration Control Number (PatientICN) assigned by the VHA Master Veteran Index. For PatientICNs associated with more than one surgical encounter during the study period, one encounter per patient was selected at random. In accordance with Anesthesia & Analgesia's policy on disclosing multiple publications derived from a single database, the above cohort is being used within several research projects examining the relationships between perioperative care and longitudinal medical follow-up.

Data used for model formation and validation

For each encounter recorded in the EHR, detailed information was extracted, including demographics (age, gender, self-identified race and ethnicity), the type of surgery, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status score (ASA score), and presurgical vital signs (blood pressures, height, and weight). For blood pressure data, healthcare encounter-level information from the period 30 days prior to, through 365 days after the index surgical procedure (including clinic type, systolic and diastolic blood pressure values, and date and time) were extracted from the EHR. Ambulatory clinic blood pressure readings included in the postoperative queries were based on clinic stop codes queried from the VHA National Patient Care Database Medical SAS Outpatient Datasets, as has been described elsewhere,26 including visits to the following non-surgical outpatient clinics: primary care clinic, cardiology clinic, pulmonology clinic, endocrinology clinic, diabetes clinic, hypertension clinic, women's clinic, infectious disease clinic, and geriatric primary care clinic. These outpatient clinics were based on the NEXUS clinic group, as defined by the VHA External Peer Review Program, a group that tracks which veterans are receiving primary care across the VHA system. In addition to the NEXUS clinic group, we added infectious disease clinics due to their frequent role as the primary care source for veterans with HIV. Blood pressure readings considered to be clinical outliers (SBP >240mmHg or <70mmHg, DBP >140mmHg or <30mmHg) were filtered during data acquisition and excluded from consideration. Structured fields that contained more than one valid blood pressure measurement with the same time-stamp of data entry were averaged. The height and weight most proximate to the beginning of surgery were extracted and converted into body mass index (BMI) calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. EHR entries of extreme heights and weights considered to be clinical outliers (i.e. heights < 58 inches or > 80 inches and weights < 80 pounds or > 499 pounds) were assumed to be invalid, and such data were excluded from models incorporating BMI (99.02% of height measurements and 99.46% of weight measurements extracted from the EHR were within these boundaries).

Preoperative comorbidity was determined from ICD9-CM codes dating from the year 2000 to the index surgery date. Veterans Aging Cohort Study comorbidity groupings were used.27 To increase the validity of ICD-9 diagnostic codes, at least two outpatient codes or one inpatient code for each comorbid grouping was required in order to qualify as positive, as previously described.28,29 The comorbid conditions used in predictive modeling were: alcoholism, anemia, anxiety disorder, atrial fibrillation, bipolar disorder, cerebrovascular disease, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), liver disease, lung disease, depression, peripheral vascular disease, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychosis, renal disease, and substance abuse. In addition to specific disease coding, we calculated the Charlson Comorbidity Index30 for each individual, using preoperative inpatient data beginning from the year 2000 through the index surgery date. Descriptive summaries of these variables are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (N = 215621)

| Variable | N (%) or Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.6 (11.7) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 204481 (94.8) |

| Body-Mass Index (kg/m2) | |

| Unknown (Missing) | 1 (<0.1) |

| Unknown (Outside Valid Range) | 92 (<0.1) |

| BMI kg/m2 | 29.1 (6.3) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | |

| Unknown | 109522 (50.8) |

| Yes | 7927 (3.7) |

| No | 98172 (45.5) |

| Race | |

| Unknown | 7381 (4.4) |

| White | 125566 (75.2) |

| Black or African-American | 30288 (18.2) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 2040 (1.2) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1596 (1.0) |

| Blood Pressure (mmHg) | |

| Preoperative and Day of Surgery Mean Systolic | 133.4 (16.5) |

| Preoperative and Day of Surgery Mean Diastolic | 76.3 (10.3) |

| Postoperative Clinic Mean Systolic | 130.0(15.3) |

| Postoperative Clinic Mean Diastolic | 74.7(10.1) |

| ASA Physical Status Score | |

| Missing | 17234 (8.0) |

| 1 | 1633 (0.8) |

| 2 | 37577 (17.4) |

| 3 | 131630 (61.0) |

| 4 | 27492 (12.8) |

| 5 | 55 (<0.1) |

| Surgical Service | |

| Cardiac Surgery | 13665 (6.3) |

| Ear, Nose, and Throat | 9645 (4.5) |

| General Surgery | 51268 (23.8) |

| Gynecology | 2065 (1.0) |

| Neurosurgery / Spine | 13266 (6.1) |

| Ophthalmology | 7524 (3.5) |

| Oral Surgery | 1167 (0.5) |

| Orthopedics | 39452 (18.3) |

| Plastic Surgery | 4151 (1.9) |

| Podiatry | 4869 (2.3) |

| Thoracic Surgery | 9996 (4.6) |

| Urology | 28049 (13.0) |

| Vascular Surgery | 24142 (11.2) |

| Other | 6362 (2.9) |

| Comorbidities (by ICD9-CM) | |

| Alcoholism | 42282 (19.6) |

| Anemia | 58320 (27.1) |

| Anxiety disorder | 31350 (14.5) |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 25722 (11.9) |

| Bipolar Disorder | 13981 (6.5) |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 17675 (8.2) |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 26906 (12.5) |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 77213 (35.8) |

| Diabetes | 77510 (35.9) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 146762 (68.1) |

| Hypertension | 168085(77.9) |

| Human Immunodeficiency Virus | 1889 (0.9) |

| Liver Disease | 19478 (9.0) |

| Pulmonary Disease | 76350 (35.4) |

| Depression | 74161(34.4) |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 46072(21.4) |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | 33555(15.6) |

| Psychosis | 24537 (11.4) |

| Renal Disease | 44823 (20.8) |

| Substance Abuse | 22034(10.2) |

| Charlson Comorbitidy Index | 1.9 (2.3) |

| Cardiovascular Medications (by VA Drug Class Code) | |

| Digoxin | 2451 (1.14) |

| Beta Blocker | 46046 (21.36) |

| Alpha Blocker | 21043 (9.76) |

| Calcium Channel Blocker | 24095 (11.17) |

| Antianginal | 14224 (6.6) |

| Antiarrythmic | 1496 (0.69) |

| Antilipemic | 52132 (24.18) |

| Thiazide type diuretic | 16976 (7.87) |

| Loop diuretic | 14542 (6.74) |

| Potassium sparing/Combination diuretic | 4628(2.15) |

| Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor | 310 (0.14) |

| Other Diuretic | 29 (0.01) |

| ACE Inhibitor | 35618 (16.52) |

| Angiotensin Receptor Blocker | 6232(2.89) |

| Direct Renin Inhibitor | 5 (0) |

| Antihypertensive combination | 4777 (2.22) |

| Other Antihypertensive | 5425 (2.52) |

| Other Cardiovascular Medication | 1536 (0.71) |

Preoperative VHA pharmacy prescription records for cardiovascular medications were extracted for the 90 days before the date of surgery. Medications were classified into relevant national VHA drug class codes, as has been previously described,31 and those used in the present analysis are listed in Table 1.

The validity of information contained within the VHA EHR is an important consideration for the present study.32 Regarding blood pressures contained in structured fields within the VHA EHR, it has been shown that they compare favorably to manually extracted clinical data, with measures of agreement for blood pressure falling in the “excellent” range (kappa=0.94, 95% sensitivity, and >99% specificity) for poorly controlled blood pressure.33

Outcome specification and data analysis

Blood pressure values were collected from the EHR for: 1) the proximate ambulatory clinic visit during the 30 days before surgery, 2) the first blood pressure recorded on the day of surgery, before the beginning of surgery, and 3) the blood pressure recorded during the four most proximate ambulatory care clinic appointments in the 12 months after surgery. The inherent variability of individual blood pressure measurements has been well established in the literature.34 Thus, for the present analyses, patients were excluded from the predictive models if they did not have blood pressures recorded as above from two timepoints before the beginning of surgery. Similarly, the postsurgical blood pressure was defined where possible as the mean SBP and DBP from four ambulatory clinic appointments in the 12-months following surgery. For patients who did not attend at least four postoperative clinic visits as described, the mean postoperative clinic blood pressure was calculated from as many visits as occurred.

Data were analyzed to determine the prevalence of poorly controlled outpatient clinic blood pressure among the national cohort, which was defined in this study according to JNC-7 guidelines14 as a mean postoperative ambulatory clinic blood pressure ≥ 140mmHg SBP, and/or 90 mmHg DBP.a

In addition to examining the prevalence of poorly controlled outpatient clinic blood pressure after surgery, four increasingly complex prediction models were developed using multivariable logistic regression to predict this outcome and were compared for their performance in guiding perioperative clinicians to make appropriate outpatient primary care referrals. The discriminative power of each model was calculated using the C-statistic, and each model was graphically represented in an ROC curve. Model 1 included only the mean of the two preoperative SBP and DBP readings; Model 2 added day of surgery demographics, surgical service (classified in Table 1 according to the subspecialty of the proceduralist as inferred from the procedure description), and ASA score; Model 3 additionally added preoperative cardiovascular prescriptions by VHA drug classes; Model 4 additionally added ICD9-CM-based comorbidity groupings and the Charlson Comorbidity Index.30 The assumption of linearity of the logit with mean preoperative SBP and DBP was visually checked in Model 1, and we determined that transformations of these variables would be unnecessary.

The possible optimism of the models was assessed via a resampling bootstrap technique to internally validate the prediction models and derive a true estimate of predictive accuracy.35 Comparative model performance, clinical utility, and ease-of-use were then considered in accordance with the general principles used in the development of other widely used clinical risk assessment models.36 The increased predictive value of the most complex model compared to the simplest model was also assessed with the use of the Net Reclassification Index (NRI) statistic,37,38 with the 95% confidence interval calculated in accordance with the method of Pencina, et al.39 For simple blood pressure thresholds, point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value were computed by the exact test of the proportion.40 All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Power and Sample Size Considerations

A priori power analysis assumed that approximately 130 VHA hospitals would provide surgical services during the period of study,41 with total surgical volume exceeding 60,000 cases per year. Thus over 5 years, approximately 300,000 surgical cases were assumed to be available, from which we estimated that 210,000 would provide valid data to inform analyses. For comparison of the crude and more saturated models, assuming a C-statistic of 0.70 in the crude model, and using a two-sided z-statistic at a significance level of 0.05, we demonstrated that the sample would have >99% power to detect an increase of 0.01 in the c-statistic of the more saturated models. This also provided sufficient data to maintain at least 10 events per predictor variable in the multivariable logistic regression models.42

Results

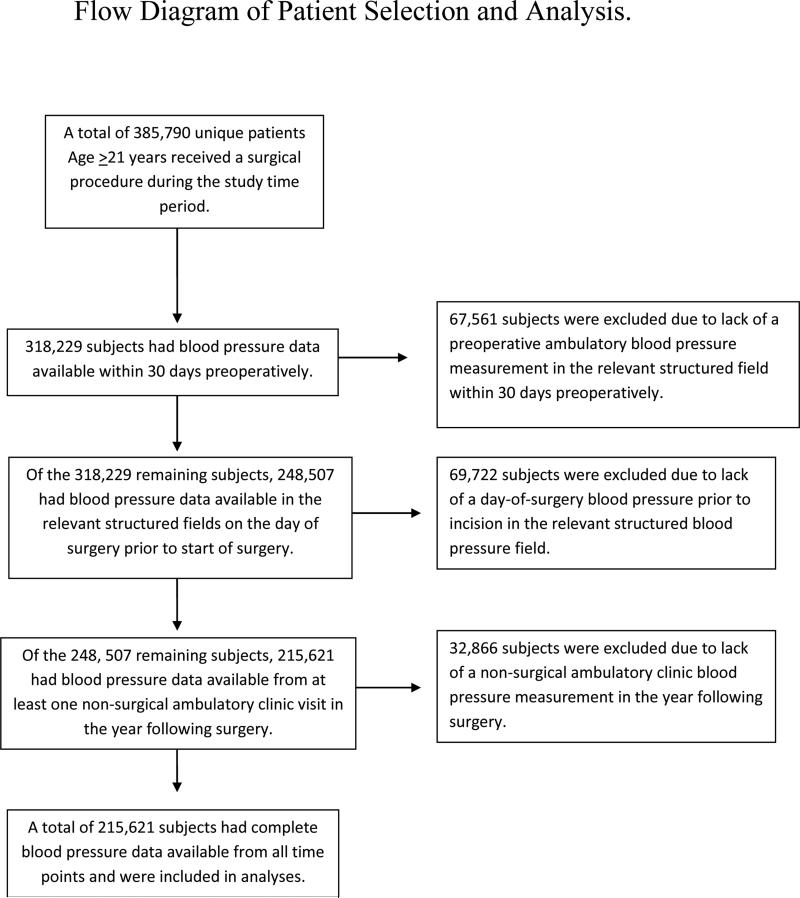

A total of 385,790 unique patients were identified for potential inclusion in analyses. Of these, 215,621 had available blood pressure data from all time points in the relevant structured fields and comprised the cohort for predictive modeling. (Consort diagram; Figure 1). The mean (±SD) age of the cohort was 63.6 years (±11.7 years); 94.8% were male; 18.2% self-identified as Black or African-American. A descriptive summary of the entire cohort is provided in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient selection and analysis.

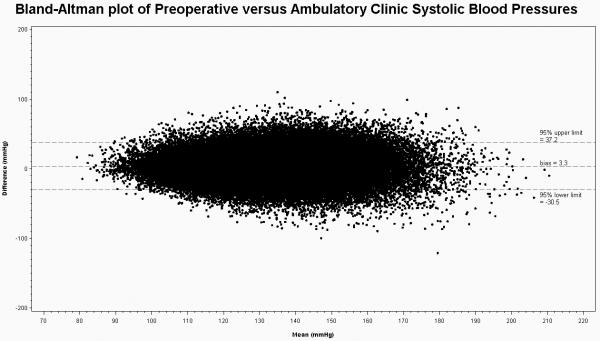

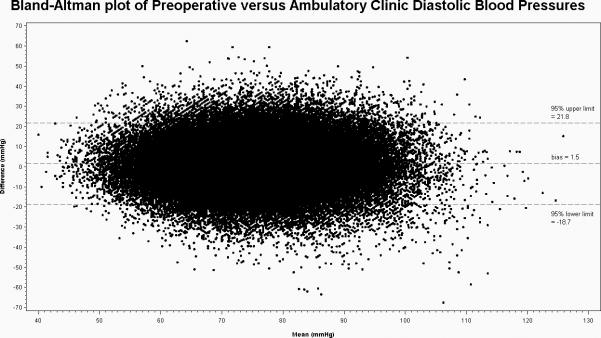

The mean preoperative SBP/DBP was 133.4mmHg (±16.5)/76.3mmHg (±10.3). The mean postoperative clinic ambulatory SBP/DBP was 130.0 mmHg (±15.3)/74.7 mmHg (±10.1). The bias between preoperative and postoperative ambulatory clinic SBP measurements was +3.4 mmHg (95% limits of agreement ±32.4) greater in the preoperative period and for DBP was +1.6 mmHg (95% limits of agreement ±19.4) greater in the preoperative period (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Bland-Altman Plot of Preoperative versus Ambulatory Clinic Systolic Blood Pressure including mean bias and crude 95% limits of agreement.

Figure 3.

Bland-Altman Plot of Preoperative versus Ambulatory Clinic Diastolic Blood Pressure including mean bias and crude 95% limits of agreement.

Prevalence of poorly controlled outpatient clinic blood pressure

The outcome of mean ambulatory clinic blood pressure ≥ 140/90mmHg in the year following surgery was observed in 55,348 patients for an overall prevalence of 25.7% (95% CI 25.5%-25.9%). Among patients without a preoperative diagnosis of hypertension or hypertension treatment the prevalence in the year after surgery was 14.2% (95% CI 13.9%-14.6%), compared to 28.3% (95% CI 28.0%-28.5%) among patients with a known preoperative hypertension history or hypertension treatment.

Predictive modeling

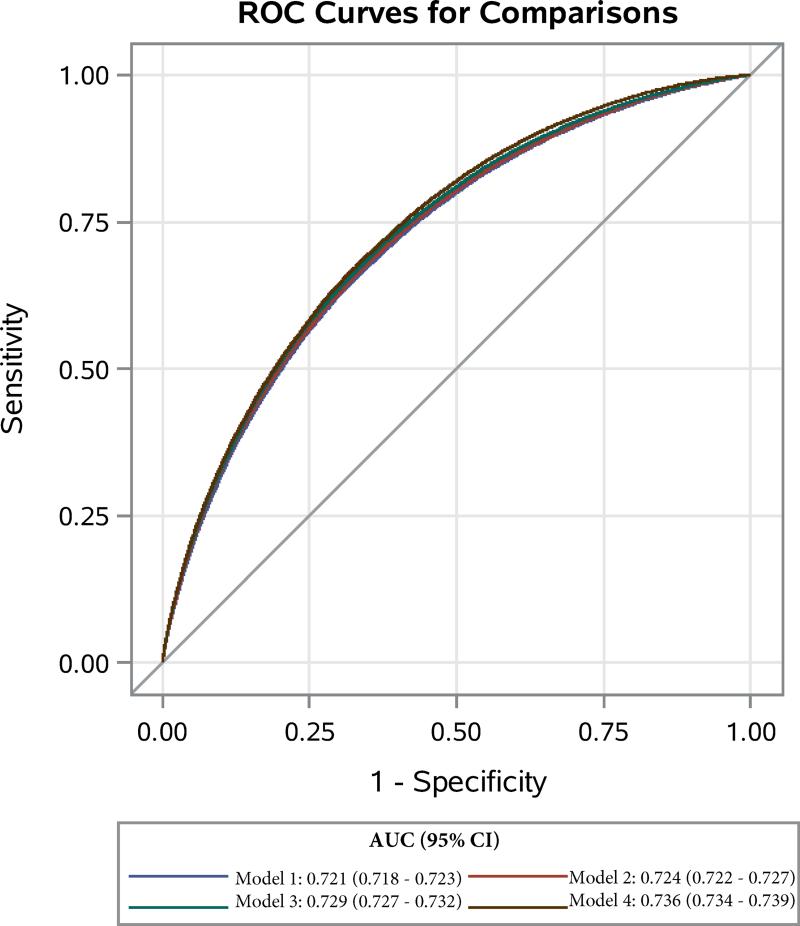

Discriminative power as measured by the C-statistic demonstrated incremental increases across the four described prediction models as follows: Model 1: 0.721 (95% CI 0.718-0.723), Model 2: 0.724 (95% CI 0.722-0.727), Model 3: 0.729 (95% CI 0.727-0.732), and Model 4: 0.736 (95% CI 0.734-0.739). P-value for difference between each model was <.0001. ROC curves of the four models demonstrating the marginal improvement in discriminative power are displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

ROC Curves and Corresponding C-Statistics with 95% confidence intervals of Four Increasingly Complex Logistic Regression Models Using Preoperative Data to Predict Postoperative Ambulatory Clinic Blood Pressure Elevation (≥140/90mmHg).

Internally validated C-statistics were calculated for Model 1 and Model 4 using resampling with replacement for 1000 iterations to assess for possible optimism of the original models. Using this method, the discriminative power for both models 1 and 4 fell within the original 95% confidence intervals of the full dataset: Model 1 C-statistic: 0.719 (95% CI 0.718-0.720) and Model 4 c-statistic: 0.736 (95% CI 0.735 – 0.737). These results provide evidence that overfitting of the original models was not present, as would be expected, given the large N in relation to the numbers of predictors.

Clinical relevance of model improvement and the Net Reclassification Improvement

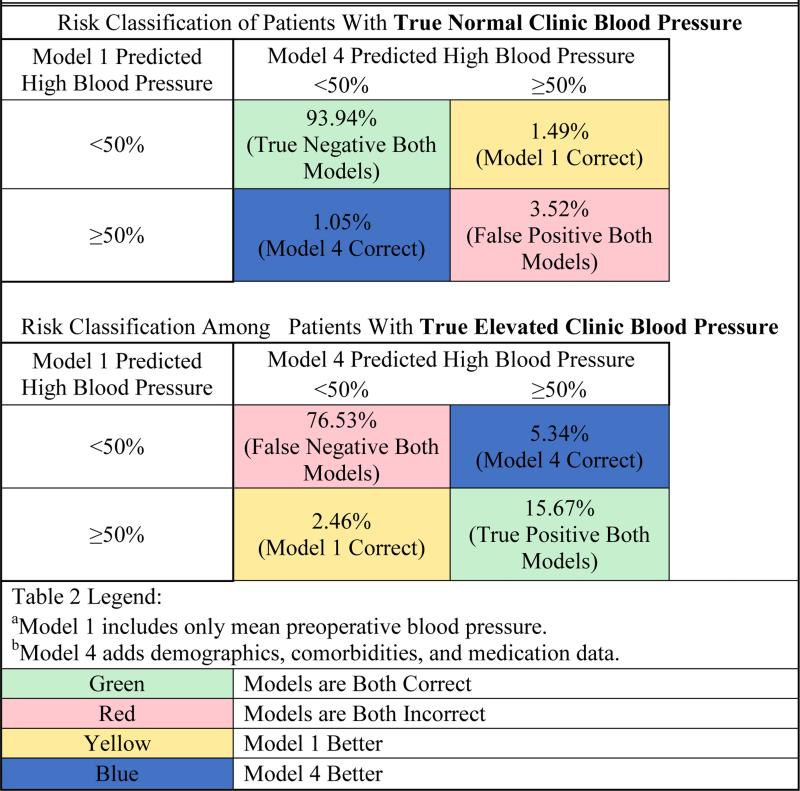

Prior investigators have demonstrated that changes in the C-statistic may poorly represent the extent to which a new model will improve care decisions.39,43 Therefore, to assess the clinical relevance of prediction improvement between the simplest and most complex model, we examined the NRI statistic.37-39 For the NRI analysis, we used risk category thresholds for postoperative ambulatory clinic hypertension of 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5. Comparing models 1 and 4, the overall NRI was 0.088 (95%CI 0.082-0.093). Given that blood pressure referral is a dichotomous intervention (i.e. a patient is either referred or not) and that unnecessary referrals for patients without elevated blood pressure would cause additional inconvenience and expense, we then examined how well the models performed within the reclassification tables in defining the group of patients who were more likely than not to have poorly controlled postoperative ambulatory clinic blood pressures. That is, among the group of patients that the models identified as having a 50% or greater likelihood of elevated postoperative clinic blood pressures, we examined how the most and least parsimonious models compared within the NRI analysis above as follows (Table 2):

Table 2.

Reclassification Improvement from Model 1a to Model 4b in Predicting Patients More Likely Than Not to Have High Blood Pressure

|

Of the patients with a true positive outcome of elevated postoperative clinic blood pressure, 5.34% were assigned a risk less than 50% in model 1 and were reclassified to the highest risk category (≥50%) in the most complex model, but 2.46% of true positive patients who had been assigned the highest risk in model 1 were reclassified to a lower risk in the more complex model. For patients with a true negative outcome (i.e. non-elevated clinic blood pressure in the 12-months postoperatively), the more complex model correctly reclassified 1.05% to a lower risk category who had been deemed high risk in the simple model but also incorrectly reclassified 1.49% of the true negative patients into the high risk category who had been more accurately assigned a lower risk category in the simple model. In sum, if 100 hypertensive and 100 normotensive patients were put into model 4 versus model 1 and referred for follow-up based on a predicted 50% or higher likelihood of post-operative hypertension, it is estimated that an additional 2.88 of the 100 patients who were truly positive for postoperative elevated blood pressure in the 12 months after surgery would have been correctly referred, but this would have come at the cost of an additional 0.44 of the 100 patients without an elevated blood pressure being referred. The absolute net improvement in correct referral decisions of this hypothetical cohort using model 4 instead of model 1 would have been an improvement of 2.44 of 200, or 1.2% of referral decisions.

Actionable thresholds based on blood pressures alone

Given our desire to develop an easy-to-use clinical prediction tool and the apparently marginal improvement of the most complex model as compared to a simple model using preoperative blood pressure to guide referral decisions, we next sought to measure the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of several easy-to-remember referral thresholds based on mean preoperative SBP and DBP of 140/90mmHg, 150/95mmHg, and 160/100mmHg (Table 3). A mean preoperative blood pressure referral threshold of ≥ 150/95mmHg demonstrated 33.7% sensitivity (95% CI 33.3-34.1), 89.1% specificity (95% CI 88.9-89.2), 51.5% PPV (95% CI 51.0-52.0), and 79.6% NPV (95% CI 79.4-79.7). This threshold would have resulted in a decision rule leading to 16.8% (95% CI 16.6-16.9) of the cohort being referred. Such a decision rule would have achieved the results of 1) referring a group of patients who were more likely than not to in fact demonstrate poorly controlled outpatient clinic blood pressure, and 2) not referring a group in which four of five were indeed normotensive during follow-up appointments.

Table 3.

Characterization of Actionable Preoperative Blood Pressure Referral Thresholds in Predicting Elevated Ambulatory Blood Pressure in the Year Following Surgery

| Mean Preoperative Blood Pressure Threshold | Percent Referred | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Positive Predictive Value (95% CI) | Negative Predictive Value (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 140mmHg Systolic and/or 90mmHg Diastolic | 35.1% (34.9-35.3) | 58.9% (58.4-59.3) | 73.1% (72.9-73.3) | 43.1% (42.7-43.4) | 83.7% (83.5-83.9) |

| 150mmHg Systolic and/or 95mmHg Diastolic | 16.8% (16.6-16.9) | 33.7% (33.3-34.1) | 89.1% (88.9-89.2) | 51.5% (51.0-52.0) | 79.6% (79.4-79.7) |

| 160mmHg Systolic and/or 100mmHg Diastolic | 6.9% (6.8-7.0) | 15.7% (15.4-16.1) | 96.1% (96.0-96.2) | 58.4% (57.7-59.2) | 76.8% (76.6-77.0) |

Discussion

In a large national cohort of surgical patients treated in VHA hospitals, poorly controlled outpatient clinic blood pressure in the year after surgery occurred in 25.7% of all patients, including 14.2% of patients with no known preoperative history of hypertension or antihypertensive treatment. Regarding the tradeoff between model performance and ease-ofuse in identifying which patients are likely to demonstrate elevated postoperative clinic blood pressures, our predictive modeling demonstrated marginal, and likely clinically trivial, improvements in predictive modeling when broad ranges of clinical and administrative data were added to a model that used preoperative blood pressures alone. A simple decision-rule using a blood pressure referral threshold ≥150/95mmHg from two preoperative readings was able to identify a subset of between 16.6-16.9% of the national cohort who, as a group, were more likely than not to demonstrate elevated outpatient clinic blood pressures (PPV lower 95% confidence limit: 51.0%) in the year following surgery. Importantly, almost four of five patients not meeting this screening criterion indeed demonstrated normal ambulatory clinic blood pressures (NPV lower 95% confidence limit: 79.4%). These findings are consistent with the notions that 1) even in the preoperative context, blood pressure does in fact perform reasonably well to predict blood pressure, and 2) despite adding large amounts of clinical and administrative data, models to predict elevated postoperative clinic blood pressures demonstrate only marginal improvement in guiding referral decisions with the disadvantage of creating a much less user-friendly decision-support tool.

Despite a health care landscape that advocates for incentivizing prevention science44 and associated campaigns such as the Millions Hearts Initiative,45 the surgical literature has, until recently, remained largely focused on outcomes directly attributable to the surgical encounter, thereby unintentionally separating the perioperative health care experience from broader national efforts to improve public health through the provision of high quality preventive medical care. Our finding that more than one in four patients demonstrated elevated ambulatory clinic blood pressures in the year after surgery provides evidence to support the notion that the public health opportunity for anesthesiologists to reduce long-term morbidity by assuring timely follow-up care for poorly controlled blood pressure is significant.

Our work adds to the growing body of literature defining the emerging concept of the Perioperative Surgical Home. This concept has motivated several groups of researchers to examine ways in which care coordination around the time of surgery may enable safer and more efficient care of patients in need of surgical interventions.46-49 Our findings also reinforce research from other investigators who have found that consistently elevated blood pressures, even within a high-stress healthcare environment such as the emergency department, are likely to reflect true blood pressure elevation, rather than merely a transient effect of being in a stressful environment.50 Prospective studies of counseling and referral efforts to improve the long-term preventive medical care of surgical populations are clearly warranted.

Several limitations of the present study deserve to be noted. First, it is not known to what extent the performance of a blood pressure referral threshold developed among United States veterans would generalize to other settings.51,52 United States veterans demonstrate a bimodal distribution in age, following historical variations in the numbers of active-duty United States military personnel. They are also more likely to be male and are more likely than the general United States population to carry a diagnosis of substance-use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and other psychiatric comorbidities. However, even in the unlikely event that our findings were entirely limited to United States veterans, our data would still apply to a growing population of several million people who together comprise the patient population of the largest single healthcare system in the United States. In addition to its large patient population, the VHA also provides the advantage of being one of the few healthcare systems that is national in scope and that follows patients longitudinally across inpatient and outpatient settings within a single, integrated EHR. Second, our models may perform differently in populations who lack timely postoperative follow-up, as the present observational study was perforce limited to patients who did have follow-up blood pressures available for analysis. Also, while blood pressures from structured fields in the VHA EHR compare quite well to manually extracted blood pressures,33 the variability in cuff sizes, patient positioning, and provider technique were unavoidable in this retrospective study. As would be expected, our analysis identified significant bidirectional variability in the relationship between preoperative and ambulatory clinic blood pressure measurements which, though similar to what has been previously reported,16 may be reduced in future prospective studies using standardized blood pressure collection methods. Among such methods, home blood pressure monitoring and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring53 performed outside of the medical clinic are increasingly used as part of primary care treatment decisions regarding hypertension, and are likely to be useful adjuncts in the present population as well. In addition, other clinical and administrative data in the VHA EHR are also prone to varying levels of inaccuracy, and the associated misclassification of comorbidities and other clinical and administrative data is a factor that has been shown to introduce bias into results from large-scale EHR data research.32 Finally, it is not known what type of blood pressure counseling or referral intervention would find acceptance from physicians and patients already encumbered with arguably more acute concerns of the perioperative period. This final limitation is an additional vital avenue of inquiry to be pursued in further prospective clinical trials.

Despite these limitations, our findings provide evidence that by identifying patients with elevated blood pressure in the perioperative period, the surgical care episode may be harnessed toward promoting long-term preventive medicine efforts. Similar work has already been pursued among anesthesiologists to promote long-term risk-factor reduction in the case of smoking cessation.54-58 Specifically, regarding elevated blood pressure, several multidisciplinary cooperative efforts among nurses, pharmacists and other physician specialists, including surgeons, have demonstrated the potential feasibility of this idea for addressing the urgent and persistent public health need of improving the longitudinal control of elevated outpatient blood pressure.59-62

In summary, we found that among surgical patients, poorly controlled postoperative ambulatory clinic blood pressure is common and may present an opportunity for anesthesiologists to improve public health through care coordination efforts focused on improving follow-up care for undertreated blood pressure elevation. Among Veterans presenting for surgery, the use of a simple approach to referral for blood pressure control based on a mean preoperative blood pressure ≥ 150/95mmHg provides a level of predictive performance that may find acceptance among clinicians and patients. Care coordination efforts by anesthesiologists, if they should succeed in improving blood pressure control in surgical patients, would be highly likely to markedly reduce long-term morbidity and mortality for this population.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number K23HL116641. This work was also supported by the Veterans Health Administration and by CTSA Grant UL1 RR024139 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the NIH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the policy or views of the NIH, the Veterans Health Administration, or the United States Government.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Although JNC-8 guidelines have since argued for a higher systolic blood pressure goal among patients over 60 years of age,15 they were published after the institution of the present protocol and have not been endorsed by the American Heart Association or the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute.

DISCLOSURES:

Name: Robert B. Schonberger, MD, MA

Contribution: This author was responsible for study design, conduct of the study, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Attestation: Robert B. Schonberger approved the final manuscript. This author attests to the integrity of the original data and the analysis reported in this manuscript. Robert B. Schonberger is the archival author.

Name: Feng Dai, PhD

Contribution: This author was responsible for study design, conduct of the study, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Attestation: Feng Dai approved the final manuscript. This author attests to the integrity of the original data and the analysis reported in this manuscript.

Name: Cynthia A. Brandt, MD, MPH

Contribution: This author was responsible for study design, conduct of the study, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Attestation: Cynthia A. Brandt approved the final manuscript. This author attests to the integrity of the original data and the analysis reported in this manuscript.

Name: Matthew M. Burg, PhD

Contribution: This author was responsible for study design, conduct of the study, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation.

Attestation: Matthew M. Burg approved the final manuscript. This author attests to the integrity of the original data and the analysis reported in this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Robert B. Schonberger, Department of Anesthesiology; Yale School of Medicine; New Haven, CT.

Feng Dai, Yale Center for Analytical Sciences; Yale School of Public Health; New Haven, CT.

Cynthia A. Brandt, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven, CT. Departments of Emergency Medicine and Anesthesiology; Yale School of Medicine; New Haven, CT.

Matthew M. Burg, Section of Cardiovascular Medicine; Department of Internal Medicine; Yale School of Medicine; New Havent, CT. VA Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven, CT.

References

- 1.Grimm RH, Jr., Cohen JD, Smith WM, Falvo-Gerard L, Neaton JD. Hypertension management in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT). Six-year intervention results for men in special intervention and usual care groups. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1191–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keil JE, Sutherland SE, Knapp RG, Lackland DT, Gazes PC, Tyroler HA. Mortality rates and risk factors for coronary disease in black as compared with white men and women. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:73–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307083290201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, Collins R, Sorlie P, Neaton J, Abbott R, Godwin J, Dyer A, Stamler J. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, Prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet. 1990;335:765–74. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90878-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miura K, Daviglus ML, Dyer AR, Liu K, Garside DB, Stamler J, Greenland P. Relationship of blood pressure to 25-year mortality due to coronary heart disease, cardiovascular diseases, and all causes in young adult men: the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1501–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stamler J, Stamler R, Neaton JD. Blood pressure, systolic and diastolic, and cardiovascular risks. US population data. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:598–615. doi: 10.1001/archinte.153.5.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terry DF, Pencina MJ, Vasan RS, Murabito JM, Wolf PA, Hayes MK, Levy D, D'Agostino RB, Benjamin EJ. Cardiovascular risk factors predictive for survival and morbidity-free survival in the oldest-old Framingham Heart Study participants. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1944–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gueyffier F, Boutitie F, Boissel JP, Pocock S, Coope J, Cutler J, Ekbom T, Fagard R, Friedman L, Perry M, Prineas R, Schron E. Effect of antihypertensive drug treatment on cardiovascular outcomes in women and men. A meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomized, controlled trials. The INDANA Investigators. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:761–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-10-199705150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neal B, MacMahon S, Chapman N, Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists C Effects of ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and other blood-pressure-lowering drugs: results of prospectively designed overviews of randomised trials. Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration. Lancet. 2000;356:1955–64. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Psaty BM, Smith NL, Siscovick DS, Koepsell TD, Weiss NS, Heckbert SR, Lemaitre RN, Wagner EH, Furberg CD. Health outcomes associated with antihypertensive therapies used as first-line agents. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 1997;277:739–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen N, Berry JD, Ning H, VAn Horn L, Dyer A, Lloyd-Jones D. Impact of Blood Pressure and Blood Pressure Change During Middle Age on the Remaining Lifetime Risk for Cardiovascular Disease: The Cardiovascular Lifetime Risk Pooling Project. Circulation. 2012;125:37–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.002774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ostchega Y, Yoon S, Hughes J, Louis T. Hypertension Awareness, Treatment, and Control - Continued Disparities in Adults: United States 2005-2006; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vital Signs: Awareness and Treatment of Uncontrolled Hypertension Among Adults - United States, 2003-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012:703–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, Calkins H, Chaikof EL, Fleischmann KE, Freeman WK, Froehlich JB, Kasper EK, Kersten JR, Riegel B, Robb JF. 2009 ACCF/AHA focused update on perioperative beta blockade incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: a report of the American college of cardiology foundation/American heart association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2009;120:e169–276. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report.[Erratum appears in JAMA. 2003 Jul 9;290(2):197]. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, Lackland DT, LeFevre ML, MackKenzie TD, Oqedeqbe O, Smith SC, Jr, Svetkey LP, Taler SJ, Townsend RR, Wright JT, Jr, Narva AS, Ortiz E. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the eighth joint national committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schonberger RB, Burg MM, Holt NF, Lukens CL, Dai F, Brandt C. The relationship between day-of-surgery and primary care blood pressure among Veterans presenting from home for surgery. Is there evidence for anesthesiologist-initiated blood pressure referral? Anesth Analg. 2012;114:205–14. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318239c4c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Junghans T, Neuss H, Strohauer M, Raue W, Haase O, Schink T, Schwenk W. Hypovolemia after traditional preoperative care in patients undergoing colonic surgery is underrepresented in conventional hemodynamic monitoring. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:693–7. doi: 10.1007/s00384-005-0065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drummond JC, Blake JL, Patel PM, Clopton P, Schulteis G. An Observational Study of the Infuence of “White-coat Hypertension” on Day-of-Surgery Blood Pressure Determinations. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2013;25:154–61. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e31827a0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kain ZN, Sevarino F, Pincus S, Alexander GM, Wang SM, Ayoub C, Kosarussavadi B. Attenuation of the preoperative stress response with midazolam: effects on postoperative outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:141–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200007000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schonberger RB. Ideal Blood Pressure Management and our Specialty: RE: Drummond, et al. “An Observational Study of the Influence of “White-coat Hypertension” on Day-of-Surgery Blood Pressure Determinations. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2014;26:270–1. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schonberger RB, Burg M, Feinleib J, Dai F, Holt NF, Brandt C. Atenolol Is Associated with Lower Day of Surgery Heart Rate as Compared to Long and Short-acting Metoprolol. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2012;27:298–304. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schonberger RB, Feinleib J, Lukens CL, Turkoglu OD, Haspel K, Burg M. Beta-blocker withdrawal among patients presenting for surgery from home. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2012;26:1029–33. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Twersky RS, Goel V, Narayan P, Weedon JL. The Risk of Hypertension after Preoperative Discontinuation of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors or Angiotensin Receptor Antagonists in Ambulatory and Same-Day Admission Patients. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:938–44. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wasson JH, Sox HC, Neff RK, Goldman L. Clinical prediction rules. Applications and methodological standards. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:793–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198509263131306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selected Veterans Health Administration Characteristics FY 2003 to FY 2009. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics; United States Department of Veterans Affairs; [June 12, 2013]. http://www.va.gov/vetdata/Utilization.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 26.VIRec Research User Guide: FY2002 VHA Medical SAS Outpatient Datasets. Edward J. Hines, Jr VA Hospital, Veterans Affairs Information Resource Center; Hines, IL: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Justice AC, Dombrowski E, Conigliaro J, et al. Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS): Overview and description. Med Care. 2006;44:S13–24. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223741.02074.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akgun KM, Gordon K, Pisani M, Fried T, McGinnis KA, Tate JP, Butt AA, Gibert CL, Huang L, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Rimland D, Justice AC, Crothers K. Risk factors for hospitalization and medical intensive care unit (MICU) admission among HIV-infected Veterans. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62:52–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318278f3fa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Justice AC, Lasky E, McGinnis KA, Skanderson M, Conigliaro J, Fultz SL, Crothers K, Rabeneck L, Rodriguez-Barradas M, Weissman SB, Bryant K. Medical disease and alcohol use among veterans with human immunodeficiency infection: A comparison of disease measurement strategies. Med Care. 2006;44:S52–60. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228003.08925.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.London MJ, Hur K, Schwartz GG, Henderson WG. Association of perioperative beta-blockade with mortality and cardiovascular morbidity following major noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 2013;309:1704–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schonberger R, Gilbertsen T, Dai F. The Problem of Controlling for Imperfectly Measured Confounders on Dissimilar Populations: A Database Simulation Study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;28:247–54. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goulet JL, Erdos J, Kancir S, Levin FL, Wright SM, Daniels SM, Nilan L, Justice AC. Measuring performance directly using the veterans health administration electronic medical record: a comparison with external peer review. Med Care. 2007;45:73–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000244510.09001.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Powers BJ, Olsen MK, Smith VA, Woolson RF, Bosworth HB, Oddone EZ. Measuring Blood Pressure for Decision Making and Quality Reporting: Where and How Many Measures? Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:781–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-12-201106210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steyerberg E. A Practical Approach to Development, Validation, and Updating. Springer; New York: 2009. Clinical Prediction Models. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sullivan LM, Massaro JM, D'Agostino RB., Sr Presentation of multivariate data for clinical use: The Framingham Study risk score functions. Stat Med. 2004;23:1631–60. doi: 10.1002/sim.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cook NR, Buring JE, Ridker PM. The effect of including C-reactive protein in cardiovascular risk prediction models for women. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:21–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cook NR, Ridker PM. Advances in measuring the effect of individual predictors of cardiovascular risk: the role of reclassification measures. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:795–802. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-11-200906020-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr., D'Agostino RB, Jr., Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27:157–72. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. discussion 207-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. [January 10, 2015]; SAS support website; http://support.sas.com/kb/24/170.html,

- 41.Neily J, Mills PD, Young-Xu Y, Carney BT, West P, Berger DH, Mazzia LM, Paull DE, Bagian JP. Association between implementation of a medical team training program and surgical mortality. JAMA. 2010;304:1693–700. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1373–9. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kerr KF, Wang Z, Janes H, McClelland RL, Psaty BM, Pepe MS. Net reclassification indices for evaluating risk prediction instruments: a critical review. Epidemiology. 2014;25:114–21. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yach D, Calitz C. New opportunities in the changing landscape of prevention. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8900. (Published Online: July 17, 2014. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.8900) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frieden TR, Berwick DM. The “Million Hearts” initiative--preventing heart attacks and strokes. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:e27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1110421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dexter F, Wachtel RE. Strategies for net cost reductions with the expanded role and expertise of anesthesiologists in the perioperative surgical home. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:1062–71. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garson L, Schwarzkopf R, Vakharia S, Alexander B, Stead S, Cannesson M, Kain Z. Implementation of a total joint replacement-focused perioperative surgical home: a management case report. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:1081–9. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kain ZN, Vakharia S, Garson L, Engwall S, Schwarzkopf R, Gupta R, Cannesson M. The perioperative surgical home as a future perioperative practice model. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:1126–30. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vetter TR, Boudreaux AM, Jones KA, Hunter JM, Jr., Pittet JF. The perioperative surgical home: how anesthesiology can collaboratively achieve and leverage the triple aim in health care. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:1131–6. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanabe P, Persell SD, Adams JG, McCormick JC, Martinovich Z, Baker DW. Increased blood pressure in the emergency department: pain, anxiety, or undiagnosed hypertension? Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:221–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Justice AC, Covinsky K, Berlin J. Assessing the Generalizability of Prognostic Information. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:515–24. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morgan RO, Teal CR, Reddy SG, Ford ME, Ashton CM. Measurement in Veterans Affairs Health Services Research: veterans as a special population. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:1573–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Appel LJ, Stason WB. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and blood pressure self-measurement in the diagnosis and management of hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:867–82. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-11-199306010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thomsen T, Tonnesen H, Okholm M, Kroman N, Maibom A, Sauerberg ML, Moller AM. Brief smoking cessation intervention in relation to breast cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Tob Res. 2010;12:1118–24. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Warner DO, American Society of Anesthesiologists Smoking Cessation Initiative Task F Feasibility of tobacco interventions in anesthesiology practices: a pilot study. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1223–8. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181a5d03e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Warner DO, Klesges RC, Dale LC, Offord KP, Schroeder DR, Shi Y, Vickers KS, Danielson DR. Clinician-delivered Intervention to Facilitate Tobacco Quitline Use by Surgical Patients. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:847–55. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31820d868d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Warner DO, Klesges RC, Dale LC, Offord KP, Schroeder DR, Vickers KS, Hathaway JC. Telephone quitlines to help surgical patients quit smoking patient and provider attitudes. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:S486–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wong J, Abrishami A, Yang Y, Zaki A, Friedman Z, Selby P, Chapman KR, Chung F. A Perioperative Smoking Cessation Intervention with Varenicline: A Double-blind, Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trial. Anesthesiology. 2012:117. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182698b42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clark CE, Smith LFP, Taylor RS, Campbell JL. Nurse led interventions to improve control of blood pressure in people with hypertension: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3995. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kinikini D, Sarfati MR, Mueller MT, Kraiss LW. Meeting AHA/ACC secondary prevention goals in a vascular surgery practice: an opportunity we cannot afford to miss. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:781–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Svarstad BL, Kotchen JM, Shireman TI, Crawford SY, Palmer PA, Vivian EM, Brown RL. The Team Education and Adherence Monitoring (TEAM) trial: pharmacy interventions to improve hypertension control in blacks. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:264–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.849992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weber CA, Ernst ME, Sezate GS, Zheng S, Carter BL. Pharmacist-physician comanagement of hypertension and reduction in 24-hour ambulatory blood pressures. Arch Intern Med. 2011;170:1634–9. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]