Abstract

Longer lives and fertility far below the replacement level of 2.1 births per woman are leading to rapid population aging in many countries. Many observers are concerned that aging will adversely affect public finances and standards of living. Analysis of newly available National Transfer Accounts data for 40 countries shows that fertility well above replacement would typically be most beneficial for government budgets. However, fertility near replacement would be most beneficial for standards of living when the analysis includes the effects of age structure on families as well as governments. And fertility below replacement would maximize per capita consumption when the cost of providing capital for a growing labor force is taken into account. While low fertility will indeed challenge government programs and very low fertility undermines living standards, we find that moderately low fertility and population decline favor the broader material standard of living

Economic behavior, abilities, and needs vary strongly over the human life cycle. During childhood and old age, we consume more than we produce through our labor. The gap is made up in part by relying on accumulated assets. It is also made up through intergenerational transfers, both public and private, that shift of resources from some generations to others with no expectation of direct repayment. Private transfers occur when parents rear their children and when older people assist their adult children or alternatively receive assistance from them. Public transfers include public education, publicly funded health care, public pensions, and the taxes to pay for these programs. Because of these economic interdependencies across age, fertility rates that are falling or already low will drive rapid population aging in economies around the world. Forty-eight percent of the world’s people live in countries where the total fertility rate (TFR) was below replacement, about 2.1 births per woman, in 2005–10. The TFR is 1.5 births per woman in Europe and 1.4 births per woman in Japan (1). With fertility this low, population growth will give way to population decline and population aging will be rapid. The median age of the Southern European population, for example, is projected to reach 50 years of age by 2040 as compared to 41 in 2010 and 27 in 1950 (1). In 2013, governments in 102 countries reported that population aging was a “major concern” and 54 countries had enacted policies intended to raise fertility (2).

This is a remarkable reversal from decades of concern about the economic and environmental consequences of high fertility and rapid population growth (3). Should we now be alarmed about low fertility, population decline, and population aging? Should governments encourage their citizens to bear more children to balance the dramatic future increase in the number and proportion of elderly?

Identifying an optimal population policy is likely to be impossible for several reasons. First, children yield direct satisfaction and impose costs on parents that are difficult or impossible to measure. Second, the environmental consequences of continuing population growth are exceedingly complex and difficult to value or weigh against other costs and benefits of low fertility. Third, assessing the welfare consequences of differences in fertility requires comparing the welfare of those not yet born to those who will never be born.

Here our goal is more modest: to examine how low fertility and population aging will influence the material standard of living. The analysis shows, first, that relatively high fertility and young populations are favorable to public finances in rich countries because they have comprehensive systems of support for the elderly. A broader analysis that incorporates private intergenerational transfers and the capital costs of equipping each new generation shows that low fertility, older populations, and gradual population decline favor the material standard of living.

The implications of low fertility and population aging depend on the age patterns of labor income, consumption, and intergenerational transfers (4–8). Estimates of economic life cycles and intergenerational transfers have not previously been available, however. The results presented here are based on estimates constructed by research teams in 40 countries following a common methodology, National Transfer Accounts (NTA) (9–11). NTA uses existing surveys, administrative data, and the United Nations System of National Accounts (SNA) to estimate the values of goods and services produced and consumed at each age and the intergenerational flows across ages through public and private transfers and assets. NTA incorporates the age dimension into SNA, thereby facilitating analysis of the macroeconomic implications of population change.

Estimated labor income by age includes wages, salaries and fringe benefits as well as an estimate of the value of labor of those who are self-employed or unpaid family workers, all averaged across the entire population at each age. Consumption includes private expenditures and goods and services produced by governments (e.g., education and health care) imputed to different ages and averaged across all individuals at a given age.

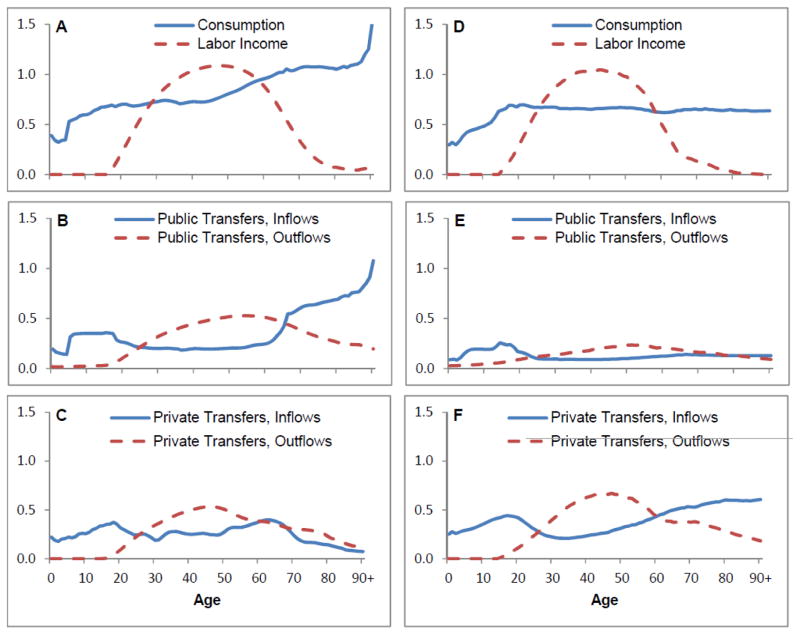

NTA age profiles for the US and Thailand illustrate the data used in the analysis (Figure 1). In the US, elderly consume far more than young adults and labor income falls off rapidly at older ages (A). Public transfer inflows to the elderly are generous, funded largely through public transfer outflows from the working ages (B). Familial transfers are important to some elderly, but on average the elderly give more than they receive at almost every age (C). In Thailand, elderly and young adults consume at similar levels. The elderly have somewhat higher labor income than in the US (D). The public system for the elderly is very modest with public transfer outflows from the elderly as great as public transfer inflows (E). Familial support is very important for the elderly with private transfer inflows higher than private transfer outflows (F).

Fig. 1.

Per capita age profiles of consumption, labor income, and public and private transfers for the US (2009) (A, B, C) and Thailand (2004) (D, E, F). Profiles are expressed relative to the mean labor income of persons 30–49 in each country.

The striking differences in shapes of labor income and consumption by age, and in public and private transfers made and received, lead to differences in the impacts population age distributions in the forty countries studied here. These differences are incorporated into two summary measures, the fiscal support ratio (FSR) and the support ratio (SR). Definitions are given below, but heuristically, the FSR is the ratio of tax payers to beneficiaries and the SR is the ratio of earners to consumers. Age profiles, FSR, and SR for all countries and complete definitions of variables are provided in the supplementary materials (9) (Box 1).

Box 1.

Key aging variables, definition, method of calculation, summary statistics, and sources (WPP is World Population Prospects 2012 Revision; NTA is National Transfer Accounts (www.ntaccounts.org, accessed July 10, 2013.) The range and mean values, except those for the TFR, are the stable values that would result if current age-specific fertility and mortality rates persist. See supplementary materials for detailed method of calculation.

| Variable | Definition and sources | Range (mean) |

|---|---|---|

| Fiscal support ratio (FSR) | Number of effective taxpayers per effective beneficiary determined by the population age distribution (WPP) and the age profiles of per capita taxes paid and benefits received for all in-kind and cash transfer programs, including education, health care, and pensions (NTA). All values expressed relative to the FSR for 2010. | 0.70 to 1.09 (0.88) |

| Mean age of consumption (AC) | Average age at which goods and services are being consumed. This is determined by the age distribution of the population (WPP) and the age profile of per capita consumption (NTA). | 28.0 to 56.9 (44.5) |

| Mean age of earning (Ayl) | Average age at which goods and services are being produced by workers. This is determined by the age distribution of the population (WPP) and the age profile of per capita labor income (NTA). | 35.2 to 47.4 (42.8) |

| Support ratio (SR) | Number of effective producers per effective consumer determined by the population age distribution (WPP) and the age profiles of per capita consumption and labor income (NTA). | 0.36 to 0.67 (0.49) |

| Total fertility rate (TFR) | Number of births per woman over the reproductive span, given current age-specific birth rates (WPP). | 1.1 to 5.6 (2.2) |

The fiscal support ratio (FSR) summarizes the influence of population age distribution on government budgets. The FSR is defined as the number of effective taxpayers, calculated by weighting the population in each age group by the average taxes paid by that age group in the base year, divided by the number of effective beneficiaries, calculated by weighting the population in each age group by per capita benefits received. A higher FSR is favorable for public finances allowing higher benefits at each age or lower taxes at each age or a smaller budget deficit or some combination of the three. A population concentrated in high tax-paying ages leads to a high FSR. A population with many children, who pay little in taxes and receive education benefits, leads to a low FSR. Likewise, a population at older ages has a low FSR in rich countries, because they emphasize pensions and health care spending on the elderly.

The support ratio (SR) summarizes the effect of the population age distribution on income and outlays per person combining both the public and the private sectors. The SR is defined as the number of effective workers, the population weighted by per capita labor income at each age, divided by the number of effective consumers, the population weighted by per capita consumption at each age. A higher SR indicates proportionally higher resources available per person allowing for higher consumption, higher saving and investment, or some combination of the two. A population concentrated at ages where labor income is high and consumption is low leads to a high SR. A population concentrated at ages where labor income is low and consumption is high leads to a low SR.

The FSR and the SR provide distinctive perspectives because intergenerational transfers through the public and private sectors are very different. Especially in rich countries, public transfers are predominantly to the elderly, while private transfers go mostly to children. As a consequence, the age structure that favors public finances is much younger than the age structure that favors the combined finances of the public and private sectors. Both a young, high fertility, rapidly growing population and an old, low fertility, rapidly declining population reduce the FSR and the SR. The central issue addressed here is what demographic conditions would be most favorable to public finances and standards of living in the long run.

The age structure of a population in the long run is determined by fertility, mortality, and migration. Our analysis emphasizes fertility because it is an important determinant of age structure and because so many governments are encouraging higher fertility due to their concerns about population aging. Mortality decline also leads to older populations but the effects are gradual and no government has ever proposed slowing mortality decline to avoid population aging. Immigration is often suggested to help reduce the population aging that results from low fertility. Immigration does lead to a younger population in the short-term, but it has a muted effect in the long-term. Immigrants are relatively young on average when they arrive, but over time their age distribution tends to become similar to or older than the age distribution of the receiving population. This occurs because the immigrant populations age and because immigrant fertility rates typically converge towards the fertility rates of the receiving population (12–14). A summary of the literature concludes “a steady stream of migrants almost always makes a population younger in the short-term but older in the long-term” (13). Net immigration also raises the population growth rate which imposes capital costs, discussed below, that must be balanced against possible benefits from age structure.

Thus, we consider the effect of fertility given the level of mortality in a population closed to migration. Given mortality and in the absence of migration, the population growth rate is determined by fertility. What level of fertility and population growth rate would maximize the FSR and SR in the long run?

Given the NTA age profiles we can easily find this level of fertility or growth rate by systematic numerical search. To gain analytic insight we can also differentiate the log of the support ratio (ln SR) with respect to the population growth rate (n), finding that ∂ ln SR/∂n = Ac − Ayl. (See supplemental materials.) Here Ac is the average age of consuming in the population and Ayl is the average age of earning. The differentiation is across long run age distributions with differing growth rates (steady state age distributions or stable population age distributions). When Ac > Ayl then earning occurs at a younger age than consumption, on average, so a younger population, achieved through higher fertility and more rapid population growth, would raise effective workers more than effective consumers, thereby raising the SR, and conversely. At the maximum long run SR these average ages are equal and the derivative equals zero (5).

The support ratio is an intuitive and widely used indicator, but it has a serious limitation. Although higher fertility might push the support ratio higher this could come at a cost – the increased saving and investment that would be required to provide capital for the growing labor force (5–8, 15–17). This “capital cost” of higher fertility and additional population growth depends on the behavioral responses of households and firms and on public policies that influence saving and investment, e.g., the extent of unfunded public pensions and health care. To deal with the uncertainty about future public policy, we consider two scenarios that in our view encompass the possible responses.

In one approach, the low capital cost case, we assume that the ratio of capital to output is constant and unaffected by changing demography. In the face of fertility decline, policies are implemented as needed to reduce saving rates to achieve this outcome. This case would be optimal for one variant of a well-known economic growth model (9, 18–19). Between 1980 and 2004, the capital-output ratio was very stable for many OECD countries including the US, with about three dollars of capital for each dollar of output produced (20). We use the average value of 3.0 to represent the low capital cost case.

For the second case, the high capital cost case, we rely on the most widely used model of economic growth, the neo-classical model. We will use an important, special case of this model in which policies are used to achieve the saving rate that leads to the economic growth path with the highest possible consumption per capita, called “golden rule” growth by economists. Under these conditions, capital per worker rises when fertility falls as has been true in Japan, many OECD countries, and recently many other high income countries (21). Under the high capital cost scenario, the capital-output ratio rises to higher levels than currently found in any country. The increase in capital due to low fertility is consistent with the view recently advanced by Piketty (22).

Again, the fertility rate that maximizes per capita consumption incorporating capital costs can be found by numerical search. For either of the cases, we can also differentiate across steady states, finding that the first order condition for maximum consumption is: d[ln (lifetime consumption)]/dn = Ac − Ayl − K/C where K is capital and C is consumption. The support ratio effect is captured by Ac − Ayl while −K/C captures the capital costs of higher fertility or more rapid population growth (9).

Table 1 reports the key results for 40 countries comparing each country’s current fertility (column B) with the fertility rate that maximizes the FSR (column C), the SR (column D), and per capita consumption for the low and high capital cost scenarios (columns E and F). Very low fertility does not adversely affect public finances in lower income countries because public programs for the elderly are quite limited and the elderly do pay taxes. For every high and upper-middle income country except South Africa and Thailand, current fertility is below the fertility level that maximizes the FSR – 3.0 and 2.9 births per woman, respectively, for upper-middle and high income countries. We expect that public transfer programs will become more generous in countries that have not yet embraced them, so that higher TFRs will maximize their FSRs in the future. At the same time future pension and health care reform in rich industrial nations and many Latin American countries may well reduce the TFRs that maximize their FSRs.

Table 1.

Current total fertility rates (TFR) and TFRs that maximize alternative objectives.

| Country/Income group | Total fertility rate 2005–10 (B) | TFR that maximizes each outcome

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal support ratio (C) | Support ratio (D) | Consumption, low capital cost scenario (E) | Consumption, high capital cost scenario (F) | ||

| All Countries | 2.44 | 2.56 | 2.05 | 1.54 | 1.24 |

| Lower income | 4.03 | 1.08 | 1.75 | 1.21 | 0.91 |

| Cambodia | 3.08 | na | 3.66 | 2.67 | 2.19 |

| Ethiopia | 5.26 | na | 1.40 | 0.91 | 0.62 |

| Ghana | 4.22 | na | 1.01 | 0.67 | 0.46 |

| India | 2.66 | 1.80 | 1.93 | 1.40 | 1.06 |

| Indonesia | 2.50 | 0.88 | 1.28 | 0.84 | 0.53 |

| Kenya | 4.80 | 1.12 | 2.07 | 1.54 | 1.26 |

| Mozambique | 5.57 | 1.30 | 1.61 | 1.12 | 0.89 |

| Nigeria | 6.00 | na | 0.96 | 0.54 | 0.29 |

| Philippines | 3.27 | 1.13 | 1.43 | 1.00 | 0.73 |

| Senegal | 5.11 | 0.25 | 1.32 | 0.67 | 0.28 |

| Vietnam | 1.89 | na | 2.60 | 1.99 | 1.67 |

| Upper-middle income | 2.09 | 2.96 | 2.01 | 1.51 | 1.20 |

| Argentina | 2.25 | 3.25 | 2.00 | 1.54 | 1.26 |

| Brazil | 1.90 | 5.45 | 2.29 | 1.82 | 1.50 |

| China | 1.63 | 2.64 | 2.17 | 1.65 | 1.34 |

| Colombia | 2.45 | 3.77 | 2.04 | 1.49 | 1.13 |

| Costa Rica | 1.92 | 3.85 | 2.31 | 1.77 | 1.42 |

| Hungary | 1.33 | 2.58 | 1.89 | 1.47 | 1.21 |

| Jamaica | 2.40 | na | 2.19 | 1.63 | 1.30 |

| Mexico | 2.37 | 2.83 | 1.98 | 1.47 | 1.14 |

| Peru | 2.60 | 3.45 | 2.17 | 1.61 | 1.26 |

| South Africa | 2.55 | 0.97 | 1.40 | 1.02 | 0.82 |

| Thailand | 1.49 | 0.79 | 2.00 | 1.55 | 1.28 |

| Turkey | 2.16 | na | 1.63 | 1.08 | 0.71 |

| High income | 1.65 | 2.94 | 2.27 | 1.78 | 1.48 |

| Australia | 1.89 | na | 2.70 | 2.06 | 1.70 |

| Austria | 1.40 | 3.74 | 2.44 | 1.90 | 1.58 |

| Canada | 1.63 | na | 1.96 | 1.55 | 1.26 |

| Chile | 1.90 | 3.63 | 2.20 | 1.69 | 1.36 |

| Finland | 1.84 | 2.92 | 2.30 | 1.83 | 1.54 |

| France | 1.97 | na | 2.41 | 1.92 | 1.61 |

| Germany | 1.36 | 3.33 | 2.55 | 2.00 | 1.65 |

| Italy | 1.38 | na | 2.11 | 1.65 | 1.34 |

| Japan | 1.34 | 2.70 | 2.33 | 1.88 | 1.57 |

| Slovenia | 1.44 | 3.25 | 2.21 | 1.78 | 1.52 |

| South Korea | 1.23 | 2.07 | 2.04 | 1.55 | 1.25 |

| Spain | 1.41 | 3.29 | 2.20 | 1.73 | 1.43 |

| Sweden | 1.89 | 3.07 | 2.15 | 1.76 | 1.49 |

| Taiwan | 1.26 | 1.85 | 2.15 | 1.70 | 1.43 |

| United Kingdom | 1.88 | 3.00 | 2.63 | 2.03 | 1.68 |

| United States | 2.06 | 2.16 | 2.33 | 1.84 | 1.50 |

| Uruguay | 2.12 | 3.22 | 1.90 | 1.47 | 1.19 |

Sources. Current TFR are most recent estimates from the United Nations Population Division (1) and refer to the period of 2005–2010. All other values calculated by authors using methods described in detail in the supplemental material. Income group based on World Bank classification for 2014 (http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups)3; lower income includes low-income and lower middle-income countries.

Notes: Results are calculated using the age-profiles of economic flows estimated for each country, a depreciation rate of 5 percent per year, and exogenous labor-augmenting technological growth of 2 percent per year.

The TFR that would maximize the support ratio (column D) is 1.8 births per woman in lower income countries, 2.0 in upper-middle income countries, and 2.3 in high income countries. These values are lower than the FSR-maximizing values because families bear most of the costs of childrearing while governments, except in lower income countries, are typically burdened more by the elderly. Still, one-third of the upper-middle income countries and all high income countries except Uruguay currently have fertility below the level that maximizes the support ratio. For high income countries, 2.3 births per woman would be “best”, on average, as compared with a current value of 1.6 births per woman. Judged in this limited way, high income countries would benefit from higher fertility.

The fertility rates that would maximize consumption, taking capital cost into account, are reported in columns E (low capital cost scenario) and F (high capital cost scenario). Using either of these measures, current fertility is higher than the consumption maximizing level in every lower income country except Vietnam and every upper-middle income country except China, Hungary, and Thailand. In all of these countries, fertility is too low using the low capital cost scenario, and too high using the high capital cost scenario. However, we emphatically are not suggesting that these lower income countries should be aiming for fertility as low as shown in Table 1. Development will likely lead to consumption and public support age profiles similar to those of richer countries.

The picture is mixed for the higher income countries. Consider the nine countries with TFRs above 1.6 births per woman in 2005–10 (Australia, Canada, Chile, Finland, France, Sweden, UK, US, and Uruguay). In these countries, the TFR exceeds or is very close to the consumption-maximizing fertility level. Under any plausible assumption about the capital costs of higher fertility, these nine countries did not have fertility rates that were too low. For seven countries with TFRs ranging from 1.2 to 1.5 for 2005–10 (Austria, Germany, Japan, Slovenia, South Korea, Spain, and Taiwan), higher fertility rates would result in higher consumption under any plausible scenario. For only one high-income country, Italy, is a definitive conclusion not possible.

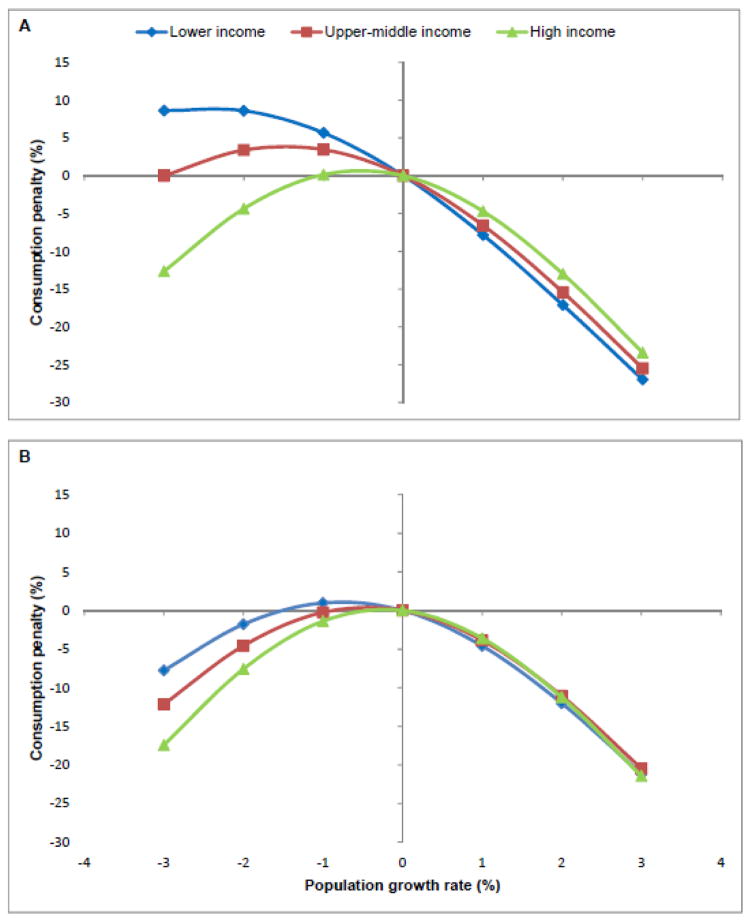

Very low fertility results in lower living standards. Given current mortality rates, no immigration, and age profiles of high income countries, a population growth rate (n) of −2% per year (TFR ≃ 1.1) would reduce per capita consumption by 4 percent relative to consumption for n=0 and TFR at replacement. Low fertility produces a smaller decline in consumption in lower and upper-middle income countries because elder consumption is not as high and because these countries have higher mortality rates (Figure 2, A). Given Japanese mortality rates, lost consumption would be greater for all income groups but especially for high-income countries – a 7.6% decline compared with consumption at replacement fertility (Figure 2, B). These costs of low fertility would be smaller for the high capital cost scenario.

Fig 2.

Effect of population growth on consumption per equivalent adult as a percentage of consumption level for zero population growth. Based on the low capital cost case assuming that the saving rate adjusts to keep the capital-output ratio constant at 3.0 given own-country mortality rates (A) and 2009 Japanese mortality rates (B). Values are simple averages for countries in three groups: lower income, upper-middle income, and high income countries. See Table 1 for countries in each group. Sources: National Transfer Accounts (ntaccounts.org) for consumption and labor income profiles; UN (2013) World Population Prospects 2012 for age specific mortality rates except for age-specific survival rates for Japan in 2009 taken from the Human Mortality Database http://www.mortality.org/ accessed October 16, 2013.

The effects of having low fertility in 2005–10 unfold gradually as the lower stable SR is reached. Among the high income countries with TFRs of 1.6 or higher, the stable SRs are about 10% less than the 2010 SRs. For high income countries with TFRs below 1.6, the stable SR is 80% of its 2010 level. For these, South Korea excluded, between 50 and 75% of the decline toward the stable SR would occur by 2030 (9)

Based on Japan, with the oldest population in the world, the effects of low fertility highlighted in this study are already beginning to emerge (9). Due to low fertility and long life the population is aging rapidly and the support ratio fell at .6% annually during the last decade while the fiscal support ratio fell even faster at .9%. However, slower and now negative labor force growth has led to reduced capital costs of equipping the new workers. Even with lower saving rates 2000–2007 (the start of the global recession) the capital output ratio has risen and, remarkably, consumption per capita also rose at more than 2% annually. It seems possible through developments in robotics that capital will be able to substitute for labor in elder care. It remains true, however, that a TFR of 1.34 (the average for 2005–2010) will impose considerable strain on public finances. Public debt is very high in Japan, making higher taxes and lower benefits a near certainty. But Japan is not experiencing economic decline and standards of living continue to increase at favorable rates for an advanced economy – faster than long-term productivity growth.

Many factors will influence the economic effects of low fertility that are not part of the formal model used in the analysis. These additional considerations, however, reinforce the basic conclusion that low fertility is not a serious economic challenge. The effect of low fertility on the number of workers and taxpayers has been offset by greater human capital investment, enhancing the productivity of workers (23). Targeted immigration policy might be helpful, although we are somewhat skeptical on this point (9). International capital flows, trade, and technological innovation may mitigate some adverse effects of population aging. Behavioral responses are likely: changes in patterns of work and consumption are already occurring. Governments are scaling back systems that are not sustainable given any likely demographic scenario.

Fiscal pressures on public programs due to population aging are real and important. If the sub-replacement fertility levels found in many countries persist, larger adjustments in public programs and retirement age will be required. The US is exceptional with a TFR close to the level best for public finances. In a number of countries, particularly those with very low fertility, standards of living would be moderately higher if fertility increased. Fertility as low as 1.6 births per woman and possibly even lower should not in itself be a matter of concern. Fertility below replacement and modest population decline favor higher material standards of living.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Lee’s research for this paper was funded by the National Institutes of Health, NIA R37 AG025247 and Lee and Mason’s research was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through a grant provided to Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Construction of NTA for many developing countries was possible due to the support of the International Development Research Centre (Canada). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors. We are grateful to Diana Stojanovic for her able research assistance. The data are available at http://ntaccounts.org/web/nta/show/Science.

Members of the NTA network designated as coauthors

Eugenia Amporfu,5 Chong-Bum An,6 Luis Rosero Bixby,7 Jorge Bravo,8 Marisa Bucheli,9 Qiulin Chen,10 Pablo Comelatto,11 Deidra Coy,12 Hippolyte d'Albis,13 Gretchen Donehower,14 Latif Dramani,15 Alexia Fürnkranz-Prskawetz,16 Robert I. Gal,17 Mauricio Holz,18 Nguyen Thi Lan Huong,19 Fanny Kluge,20 Laishram Ladusingh,21 Sang-Hyop Lee,22 Thomas Lindh,23 Li Ling,24 Giang Thanh Long,25 Maliki,26 Rikiya Matsukura,27 David McCarthy,28 Iván Mejía-Guevara,29 Teferi Mergo,30 Tim Miller,31 Germano Mwabu,32 M.R. Narayana,33 Vanndy Nor,34 Gilberto Mariano Norte,35 Naohiro Ogawa,36 Olanrewaju Ademola Olaniyan,37 Javier Olivera,38 Morne Oosthuizen,39 Mathana Phananiramai,40 Bernardo Lanza Queiroz,41 Rachel H. Racelis,42 Elisenda Rentería,43 James Mahmud Rice,44 Joze Sambt,45 Aylin Seçkin,46 James Sefton,47 Adedoyin Soyibo,48 Jorge A. Tovar,49 An-Chi Tung,50 Cassio M. Turra,51 B. Piedad Urdinola,52 Risto Vaittinen,53 Reijo Vanne,54 Marina Zannella,55 Qi Zhang,56.

Footnotes

This manuscript has been accepted for publication in Science. This version has not undergone final editing. Please refer to the complete version of record at http://www.sciencemag.org/. The manuscript may not be reproduced or used in any manner that does not fall within the fair use provisions of the Copyright Act without the prior, written permission of AAAS.

Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

Department of Economics, Sungkyunkwan University, Republic of Korea

Costa Rica

United Nations DESA-Population Division, New York, The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations

Department of Economics, Universidad de la República, Montevideo, Uruguay

Institute of Population and Labor Economics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

Centro de Estudios de Población-CENEP, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Planning Institute of Jamaica, Kingston, Jamaica

Paris School of Economics, University of Paris

Demography Department, University of California, Berkeley

Universite de Thiès/CREFAT, Senegal

Vienna University of Technology

Demographic Research Institute and TARKI Social Research Institute, Budapest

UNESCO, Regional Bureau for Education in Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago, Chile

Institute of Labour Science and Social Affairs (ILSSA), Ministry of Labour, Invalids, and Social Affairs (MoLISA), Vietnam

Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock, Germany

International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India

Center for Korean Studies, University of Hawaii at Manoa

(deceased)

National School of Development, Peking University

Institute of Public Policy and Management, National Economics University, Vietnam

BAPENAS, Jakarta, Indonesia

Nihon University Population Research Institute (NUPRI), Tokyo

National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR), UK

Center for Population and Development Studies, Harvard School of Public Health, Cambridge Massachusetts

University of California, Berkeley

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago, Chile

University of Nairobi, Kenya

Institute for Social & Economic Change, Bangalore, India

National Institute of Statistics, Cambodia

UNFPA Mozambique

Nihon University Population Research Institute (NUPRI), Tokyo

Department of Economics, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

Institute for Research on Socio-Economic Inequality, University of Luxembourg

School of Economics, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Thailand Development Research Institute

CEDEPLAR - Department of Demography, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte MG, Brazil

School of Urban and Regional Planning, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines

International Agency for Research on Cancer and Universitat de Barcelona

Australian Demographic and Social Research Institute, Australian National University

Faculty of Economics, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia

İstanbul Bilgi University

Imperial College Business School, UK

Department of Economics, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

Department of Economics, Universidad de los Andes-Bogotá

Institute of Economics, Academia Sinica Taiwan

Department of Demography, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte MG, Brazil

Department of Statistics, Universidad Nacional de Colombia-Bogotá

Finland Centre for Pensions, Helsinki, Finland

Finnish Pension Alliance TELA, Helsinki, Finland

Institute of Mathematical Methods in Economics, Vienna University of Technology

Department of Economics, University of Ottawa, Canada

Contributor Information

Ronald Lee, Email: rlee@demog.berkeley.edu.

Andrew Mason, Email: amason@hawaii.edu.

References and Notes

- 1.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Population Division. World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision. United Nations; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Population Division. World Population Policies Database 2013. United Nations; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloom DE, Canning D, Sevilla J. The Demographic Dividend: A New Perspective on the Economic Consequences of Population Change. RAND; Santa Monica, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arthur WB, McNicoll G. Samuelson, population and intergenerational transfers. Int Ec Rev. 1978;19:241–246. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willis RJ. Life cycles, institutions and population growth: A theory of the equilibrium interest rate in an overlapping-generations model. In: Lee RD, Arthur WB, Rodgers G, editors. Economics of Changing Age Distributions in Developed Countries. Oxford Univ. Press; New York: 1988. pp. 106–138. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee RD. The Formal demography of population aging, transfers, and the economic life cycle. In: Martin LG, Preston SH, editors. Demography of Aging. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C: 1994. pp. 8–49. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee RD. Population, age structure, intergenerational transfers, and wealth: A New approach, with applications to the USThe Family and Intergenerational Relations. Gertler P, editor. J Human Res. 1994;XXIX:1027–1063.

- 8.Lee R, Mason A, editors. Population Aging and the Generational Economy: A Global Perspective. Edward Elgar; Cheltenham, UK: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Information on materials and methods is available on Science Online.

- 10.Mason A, Lee R, Tung A-C, Lai MS, Miller T. Population aging and intergenerational transfers: Introducing age into National Accounts. In: Wise D, editor. Developments in the Economics of Aging. NBER, Univ. Chicago Press; 2009. pp. 89–126. [Google Scholar]

- 11.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Population Division. National Transfer Accounts Manual: Measuring and Analyzing the Generational Economy. United Nations; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Espenshade TJ, Bouvier LF, Arthur WB. Immigration and the stable population model. Demog. 1982;19:125–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein JR. How Populations Age. In: Uhlenberg Peter., editor. International Handbook of Population Aging. Dordrecht: Springer; 2009. pp. 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmertmann CP. Immigrant’s ages and the structure of stationary populations with below-replacement fertility. Demog. 1992;29:595–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samuelson P. The Optimum growth rate for population. Int Ec Rev. 1975;16:531–538. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samuelson P. The Optimum growth rate for population: Agreement and evaluations. Int Ec Rev. 1976;17:516–525. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deardorff AV. The Optimum growth rate for population: Comment. Int Ec Rev. 1976;17:510–514. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calvo G, Obstfeld M. Optimal time-consistent fiscal policy with finite lifetimes. Econometrica. 1988;56:411–432. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cutler D, Poterba J, Sheiner L, Summers L. An Aging society: Opportunity or challenge? Brookings Papers Econ Act. 1990:1–56. 71–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Backus D, Henriksen E, Storesletten K. Taxes and the global allocation of capital. J Monetary Econ. 2008;55:48–61. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feenstra RC, Inklaar R, Timmer MP. [accessed June 22, 2014];The Next Generation of the Penn World Table. 2013 www.ggdc.net/pwt.

- 22.Piketty T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee R, Mason A. Fertility, Human Capital, and Economic Growth over the Demographic Transition. Euro J Popul. 2010;26:159–182. doi: 10.1007/s10680-009-9186-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee RD, Lee S-H, Mason A. Charting the Economic Lifecycle. In: Prskawetz A, Bloom DE, Lutz W, editors. Population Aging, Human Capital Accumulation, and Productivity Growth. a supplement to Popul. Dev. Rev. 33, 208–237 (2008) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coale A. The Growth and Structure of Human Populations: A Mathematical Investigation. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton Univ. Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Preston SH. Relations Between Individual Life Cycles and Population Characteristics. Am Soc Rev. 1982;47:253–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samuelson P. An Exact Consumption Loan Model of Interest with or without the Social Contrivance of Money. J Polit Econ. 1958;66:467–482. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solow RM. A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth. Q J Econ. 1956;70:65–94. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bermingham JR. Immigration: Not a Solution to Problems of Population Decline and Aging. Pop Environ. 2001;22:355–363. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith JP, Edmonston B, editors. The New Americans: Economic, Demographic, and Fiscal Effects of Immigration. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Storesletten K. Sustaining Fiscal Policy through Immigration. J Polit Econ. 2000;108:300–323. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auerbach AJ, Oreopoulos P. Analyzing the Fiscal Impact of U.S. Immigration. Am Econ Rev. 1999;89:176–180. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonin H, Raffelhüschen B, Walliser J. Can Immigration Alleviate the Demographic Burden? FinanzArchiv: Publ Fin Anal. 2000;57:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee SH, Mason A. International Migration, Population Age Structure, and Economic Growth in Asia. Asia-Pac Migr J. 2011;20:195–213. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.