Abstract

Objectives

We used an individual-based model to evaluate the effects of hypothetical prevention interventions on HIV incidence trajectories in a concentrated, mixed epidemic setting from 2011 to 2021, and using Cabo Verde as an example.

Methods

Simulations were conducted to evaluate the extent to which early HIV treatment and optimization of care, HIV testing, condom distribution, and substance abuse treatment could eliminate new infections (i.e., reduce incidence to less than 10 cases per 10,000 person-years) among non-drug users, female sex workers (FSW), and people who use drugs (PWUD).

Results

Scaling up all four interventions resulted in the largest decreases in HIV, with estimates ranging from 1.4 (95%CI:1.36–1.44) per 10,000 person-years among non-drug users to 8.2 (95%CI:7.8–8.6) per 10,000 person-years among PWUD in 2021. Intervention scenarios targeting FWS and PWUD also resulted in HIV incidence estimates at or below 10 per 10,000 person-years by 2021 for all population sub-groups.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that scaling up multiple interventions among entire population is necessary to achieve elimination. However, prioritizing key populations with this combination prevention strategy may also result in a substantial decrease in total incidence.

Keywords: individual-based model, condom use, female sex workers, Monte Carlo simulation, people who use drugs, substance use

INTRODUCTION

Despite recent advances in HIV prevention and treatment, settings throughout the world continue to contend with ongoing HIV transmission, particularly among vulnerable sub-populations (Papworth et al. 2013). Female sex workers (FSW) and people who use drugs (PWUD) are two key affected populations which, in many regions, experience elevated HIV prevalence and poor access to HIV care and treatment (UNAIDS 2013). FSW and PWUD also act as important “core” risk groups, in which HIV transmission is both sustained and spread to the lower-risk population (Papworth et al. 2013). Several HIV prevention strategies have been proposed, which include (but are not limited to) HIV testing, condom distribution, substance abuse treatment, and a scale-up of early HIV treatment (Kurth et al. 2011; Marshall et al. 2012; Padian et al. 2011; Piot et al. 2008; Vermund and Hayes 2013). An expanding body of work suggests that a combination of some or all of these interventions may be more efficacious at preventing HIV than interventions implemented in isolation (Kurth et al. 2011; Marshall et al. 2014; Vermund and Hayes 2013).

Of particular interest is the extent to which combination prevention strategies may reduce or even eliminate HIV transmission in concentrated epidemic settings characterized by a high disease burden in overlapping, key at-risk groups (e.g., FSW and PWUD). To set an elimination target for the purposes of this study, we used the “HIV elimination phase” definition proposed by Granich et al. (2009) as a reduction in HIV incidence to less than ten cases per 10,000 people per year. To that end, it may be instructive to consider the case of Cabo Verde. This isolated country is a small archipelago of 10 islands, located 350 miles off the west coast of Africa. Its estimated total population is 491,875 (INE 2010). Reflective of other epidemics in West Africa, HIV transmission is concentrated in key affected groups (Ekouevi et al. 2013; Papworth et al. 2013; Peitzmeier et al. 2014; Vuylsteke et al. 2012). Similar to the neighboring countries of Senegal and Gambia, both HIV-1 and HIV-2 circulate in Cabo Verde; however, HIV-1 has been the predominant HIV type in Cabo Verde over the last decade (DOHCV 2011).

According to a recent national survey, the estimated HIV prevalence in Cabo Verde in 2010 was 0.8% (DOHCV 2011; INE et al. 2008). A 2010 survey (Monteiro and Sylva 2011) found that among PWUD, HIV prevalence was 3.6%. Another national survey found HIV prevalence to be 5.3% among FSW and 6.0% among participants who were both FSW and PWUD (Monteiro and Sylva 2011; Sylva et al. 2011). Moreover, the number of new infections has continued to increase, from 299 in 2006 to 411 in 2010. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have suggested that one of the main obstacles to eliminating new HIV infections in Cabo Verde is the low rate of active antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation, particularly among FSW and PWUD (UNAIDS 2012).

Given recent calls from the Department of Health of Cabo Verde (DOHCV) that urgent intervention and action are required to address HIV risk among PWUD and FSW populations (Monteiro and Sylva 2011; Sylva et al. 2011), we sought to investigate HIV transmission and assess HIV prevention strategies that will inform how to reduce new HIV infections in Cabo Verde. This work may also have important implications for other settings in which concentrated HIV transmission among overlapping and key-affected groups dominate.

METHODS

We used an individual-based model to simulate HIV incidence within an artificial society of N=305,000 “agents”, representing the entire adult Cabo Verde population aged 15 to 64 (INE 2010). We adapted an individual-based model which had been previously developed and described in detail elsewhere (Marshall et al. 2014; Marshall et al. 2012). We re-constructed the model to reflect the adult heterosexual Cabo Verde population, and re-calibrated the simulations to national data, as described below and in the Online Resource.

HIV conceptual network model

In the Cabo Verde individual-based model, agents were constructed and placed in a dynamic heterosexual and drug-using network (see Figures S1 and S2 in the Online Resource). The model was parameterized with sociodemographic, epidemiologic, and health service utilization data from Cabo Verde (DOHCV 2011; INE et al. 2008; Monteiro and Sylva 2011; Sylva et al. 2011; UNAIDS 2012). The agents were characterized by two time-varying drug use categories (PWUD, and non-drug users), and stratified by sex (male, female). Female agents can be sex workers; these agents can also use drugs. Female sex workers were modeled as their own class of agents, since their HIV prevalence is several folds higher than the general population (Sylva et al. 2011; UNAIDS 2012).

HIV transmission between serodiscordant agents is modeled as occurring when two connected agents engage in unprotected sex; the probability of engagement in sexual risk behavior, and therefore the conditional likelihood that HIV transmission occurs, varies by gender, drug use status, and sex worker status (see Tables 2 and 3). The model incorporates four evidence-based HIV prevention programs: voluntary counseling and HIV testing (VCT), early HIV treatment and optimization of care, condom distribution, and substance abuse treatment (see Figure S1 in the Online Resource), which have been implemented in Cabo Verde by the National Program to Fight AIDS (PNLS, abbreviation in Portuguese) and the Coordination Committee for the Fight Against AIDS (CCS-SIDA, abbreviation in Portuguese) (INE et al. 2008; Monteiro and Sylva 2011; Sylva et al. 2011).

Table 2.

Initial parameter estimates and data sources for non-drug users agents, in Cabo Verde at year 2010

| Variable | Base Estimate | Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| HM | HF | FSW | ||

|

| ||||

| Demographics | (DOHCV, 2011; INE et al., 2008) | |||

| HIV prevalence (%) | 1.1 | 1.2 | 4.0 | |

| AIDS prevalence (%) | 0.7 | 4.1 | ||

| Proportion of HIV+ on ART (%) | 27.0 | 26.0 | 13.0 | |

| All-cause mortality rate (per 1,000 person-years) | ||||

| Among HIV− agents | 5 | |||

| Among HIV+ agents, not on ART | 40 | |||

| Among HIV+ agents, on ART | 8 | |||

| Among agents diagnosed with AIDS | 80 | |||

| Risk Behaviors | (DOHCV, 2011; INE et al., 2008) | |||

| Unprotected intercoursea (annual probability) | 0.28 | 0.54 | 0.47 | |

| Reduction in sexual risk following HIV+ test (%) | 28 | 54 | 39 | |

| Network Parameters | (DOHCV, 2011; INE et al., 2008) | |||

| Number of annual sexual partnersb | NB(r=1,p=0·75)b | NB(r= 3,p=0·5)b | ||

| Sexual activity with partner(s) (annual probability) | 0.20 | |||

| HIV Testing & Counseling (annual probability) | 0.15 | |||

| HIV Treatment Parameters (annual probability) | (DOHCV, 2011, 2012; UNAIDS, 2012) | |||

| ART initiation | 0.40 | 0.30 | ||

| ART discontinuation | 0.18 | 0.25 | ||

| Proportion achieving ≥90% adherence to ART (%)c | 0.74 | 0.50 | ||

Abbreviations: AIDS – acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; ART – antiretroviral therapy; HF – heterosexual female; HIV – human immunodeficiency virus; HM – heterosexual male; NB – negative binomial distribution; FSW – female sex workers

Notes:

– defined as <100% correct condom use between agent dyads;

– number of partners sampled from a negative binomial distribution with parameters number of failures r and success probability p.

– proportion of agents achieve ≥90% of adherence upon initiating ART (the remaining agents are assigned randomly to four other quartiles [0% - 29%, 30% - 49%, 50% - 69%, 70% - 89%])

Table 3.

Initial parameter estimates and data sources for drug-using agents, in Cabo Verde at year 2010

| Variable | Base Estimate | Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| HM | HF | FSW | ||

|

| ||||

| Demographics | (Monteiro and Sylva, 2011; Sylva et al., 2011) | |||

| HIV prevalence (%) | 6.9 | 7.8 | 6.0 | |

| AIDS prevalence (%) | 4.1 | |||

| Proportion of HIV+ on ART (%) | 15.0 | 13.0 | ||

| All-cause mortality rate (per 1,000 person-years) | ||||

| Among HIV− agents | 5 | |||

| Among HIV+ agents, not on ART | 40 | |||

| Among HIV+ agents, on ART | 10 | |||

| Among agents diagnosed with AIDS | 80 | |||

| Risk Behaviors | (Monteiro and Sylva, 2011; Sylva et al., 2011) | |||

| Unprotected intercoursea (annual probability) | 0.36 | 0.53 | 0.28 | |

| Reduction in sexual risk following HIV+ test (%) | 36 | 53 | 27 | |

| Reduction in using drugs with SA treatment (%) | 14.60 | |||

| Network Parameters | (DOHCV, 2011, 2012; Latkin et al., 2003; Monteiro and Sylva, 2011; UNAIDS, 2012) |

|||

| Number of annual sexual and/or drug user partnersb | NB(r = 3, p = 0·5)b | |||

| Behavior with partner(s) (annual probability) | ||||

| Sexual activity exclusively | 0.20 | |||

| Drug use activity exclusively | 0.60 | |||

| Substance Abuse Treatment (annual probability) | (Monteiro and Sylva, 2011) | |||

| Probability of initiation | 0.09 | |||

| Discontinuationc at t = j, given initiation at t < j | 0.15 | |||

| HIV Testing & Counseling (annual probability) | 0.14 | (Monteiro and Sylva, 2011) | ||

| HIV Treatment Parameters (annual probability) | (DOHCV, 2011, 2012; Monteiro and Sylva, 2011; UNAIDS, 2012) | |||

| ART initiation, given no SA treatment | 0.08 | 0.30 | ||

| ART initiation, given SA treatment | 0.14 | |||

| ART discontinuation, given no SA treatment | 0.25 | |||

| ART discontinuation, given SA treatment | 0.15 | |||

| Proportion achieving ≥90% adherence to ART (%)d, given no SA treatment |

0.50 | |||

| Proportion achieving ≥90% adherence to ART (%)d, given SA treatment |

0.74 | |||

Abbreviations: AIDS – acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; ART – antiretroviral therapy; HF – heterosexual female; HIV – human immunodeficiency virus; HM – heterosexual male; NB – negative binomial distribution; SA – substance abuse; FSW – female sex workers

Notes:

– defined as <100% correct condom use between agent dyads;

– number of partners sampled from a negative binomial distribution with parameters number of failures r and success probability p;

– agents who discontinue treatment at t = j can re-initiate treatment at some t > j with probability p = 0·18;

– proportion of agents who achieve ≥90% of adherence upon initiating ART (the remaining agents are assigned randomly to four other quartiles [0% - 29%, 30% - 49%, 50% - 69%, 70% - 89%])

Study data

To parameterize the model, we conducted a comprehensive review of country-level HIV surveillance and epidemiological data, and calibrated the individual-based model to key HIV-related outcomes of interest, including AIDS mortality, ART coverage, and HIV incidence. We used data from the national surveys to estimate PWUD HIV prevalence, FSW HIV prevalence, FSW/PWUD HIV prevalence, HIV and AIDS prevalence, all-cause mortality rates, and other key initial parameters for the individual-based model at year 2010 (see Tables 2 and 3, and the Online Resource).

Table 1 shows the Cabo Verde population distribution, specified when the individual-based model is initialized, such that the agent population represents a population-based heterosexual and drug-using network of adults living in Cabo Verde at year 2010 (DOHCV 2011; INE et al. 2008; Monteiro and Sylva 2011; Sylva et al. 2011; UNAIDS 2012). At the first time step, gender and drug use statuses are attributed randomly to agents, such that 7.6% are PWUD. Among PWUD and non-drug users, 4.0% and 5.0% are FSW, respectively.

Table 1.

Initial population distribution of the individual-based model (row percentages), in Cabo Verde at year 2010

| Population group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HM | HF | FSW | Total | |

| PWUD | 50.5% | 45.5% | 4.0% | 7.6% |

| Non-drug users | 49.5% | 45.5% | 5.0% | 92.4% |

| Total | 49.5% | 45.5% | 5.0% | 100.0% |

Abbreviations: PWUD – people who use drugs; HM – heterosexual male; HF – heterosexual female; FSW – female sex workers. Note: proportions estimated from: (DOHCV, 2011; INE et al., 2008; Monteiro and Sylva, 2011; Sylva et al., 2011; UNAIDS, 2012)

We defined unprotected intercourse between two agents as less than 100% correct and consistent condom use. Tables 2 and 3 show the annual probability of unprotected intercourse, based on data from nationally representative surveys of sexual behavior and seroprevalence among PWUD (Monteiro and Sylva 2011), FSW (Sylva et al. 2011), and the non-drug users Cabo Verde population (DOHCV 2011; INE et al. 2008).

Regardless of HIV testing status, we assume that each agent dyad engages in a total of 20 unprotected sexual acts (“trials”) in an annual time step (Downs and De Vincenzi 1996). We obtained the annualized per partnership risk of HIV transmission between serodiscordant agents, assuming that it follows a Bernoulli process with 20 “trials”, and per-act HIV transmission probabilities, as shown in Table S2 (Online Resource). We assume that if an agent is aware of their HIV-positive status (i.e., VCT has been accessed at a previous time step) the probability of engaging in unprotected intercourse at all subsequent time steps is 50% less (Iliyasu et al. 2011). The decrease in unprotected intercourse probability following an HIV positive diagnosis also holds for each one of the intervention strategies described in the next subsection. We increased the per-act risk of infection during acute phase by multiplying this probability by 4.3 during the first time step that follows seroconversion, which represent the average increase that was showed in (Hughes et al. 2012; Wawer et al. 2005), see Table S2 in the Online Resource.

Model hypothetical intervention strategies

Simulations were conducted to evaluate early HIV treatment and optimization of care, HIV testing, condom distribution, substance abuse treatment, and combination of all strategies, as defined in Table S1 (Online Resource). We define the status quo as the scenario that reflects current intervention availability and coverage in Cabo Verde, using the initial parameter values for non-drug users and PWUD presented in Tables 2 and 3, and considered it as the referent scenario for comparison with other intervention strategies. Overall, the scenarios we tested were based on WHO/UNAIDS recommendations, and the baseline rates were scaled up/down according to the five year objectives presented in the “2011-2015 III Strategic Plan to Fight AIDS” (UNAIDS 2012). Specifically, in the second scenario (2), HIV testing rates in all agent strata were doubled (i.e., from 15.0%, 14.0% and 27.0% to 30.0%, 28.0% and 54.0% among non-drug users, PWUD and FSW, respectively). In the third scenario (3), we tested the effect of increasing rates of condom use by 33.3% (i.e., from 59.0%, 55.6% and 55.3% to 78.5%, 74.0% and 73.8% among non-drug users, PWUD and FSW, respectively). In 2011, 2.7 million condoms were distributed in Cabo Verde ” (UNAIDS 2012); thus, the third scenario represents an increase of close to 1 million additional condoms distributed each year.

In the next intervention scenario (4), defined as “increase substance abuse treatment”, we doubled the rate of initiating substance abuse treatment, i.e. from 9.2% to 18.4% (and decreased the rate of discontinuing substance abuse treatment and relapse by 50%). Agents that access substance abuse treatment reduce drug use by 50% (i.e., from 14.6% to 7.3%) (Monteiro and Sylva 2011; Sylva et al. 2011). In the fifth scenario (5), we scaled-up early HIV treatment and optimization of care by increasing the rate of ART initiation by 100% (i.e., from 40.0% to 80.0% among non-drug users, from 30.0% to 60.0 % among FSW, from 8.0% to 16.0% among PWUD, and from 14.0% to 28.0% among PWUD in substance abuse treatment). We also decreased the rate of ART discontinuation by 50% (i.e., from 17.8% to 8.9% among non-drug users, from 25.0% to 12.5 % among FSW and PWUD, and from 15.0% to 7.5% among PWUD in substance abuse treatment), and improved adherence to ART by 33.3% (i.e., from 73.5% to 97.8% among non-drug users and PWUD in substance abuse treatment, and from 50.0% to 66.5% among FSW and PWUD). In the final scenario (6), all interventions were combined and scaled up simultaneously, in a “combination prevention” approach. The analyses described above were conducted considering the entire population, and also prioritizing the FSW and PWUD. Sensitivity analyses were performed to examine model robustness and to account for the uncertainty in the model processes and parameter estimates (Online Resource).

The simulation of 305,000 agents was repeated 100 times for each scenario to account for uncertainty in model parameters and stochasticity in the processes represented. Mean estimates and 95 percent confidence intervals for HIV incidence in the populations of non-drug users and PWUD, and other “outputs” of interest were obtained.

RESULTS

Trends in HIV infections among PWUD and non-drug users

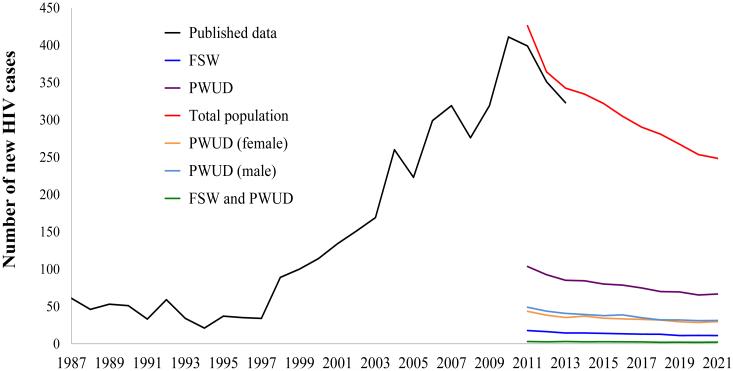

The calibrated model suggested that the number of new cases of HIV would start to decrease in 2012 (see Figure 1). Specifically, the simulation predicted 365 (95%CI: 326 – 402) new cases of HIV for the Cabo Verde population in 2012, which is similar to the reported number of new cases (351) published by the DOHCV (Delgado et al. 2013). The model predicted an HIV prevalence of 1.4 (95%CI: 1.3–1.5) in 2011 and 1.7 (95%CI: 1.7–1.8) in 2021 among non-drug users. Figure 1 shows similar decreasing trends for the estimated number of new cases of HIV among risk sub-groups of interest, stratified by gender.

Fig. 1. Number of annual newly diagbosed HIV cases in adult Cabo Verde population 1987-2010 (published data), and 2011-2021 (simulation).

Black line represents historic empirical data (DOHCV 2011; INE et al. 2008; UNAIDS 2012). The individual-based model was not designed to reproduce the epidemic historically (from 1987 to 2010), given that HIV-2 was predominant during the period between 1987 and 1998 and the model was parameterized for HIV-1 transmission.

Abbreviations: FSW – female sex workers; HIV – human immunodeficiency virus; PWUD – people who use drugs

Intervention strategies

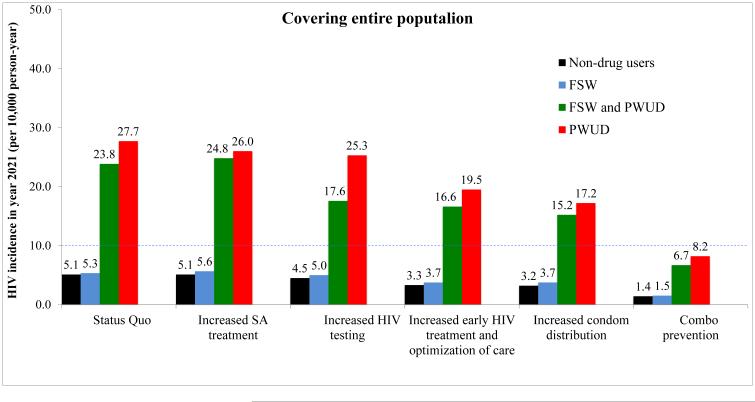

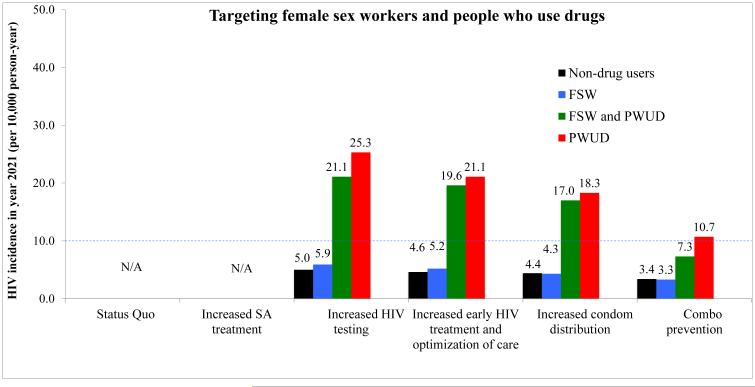

In Figure 2, we show the results of the hypothetical intervention scenarios (considering the entire population and by prioritizing the FSW and PWUD), on HIV incidence over a 10-year time period (i.e., from 2011 to 2021). Assuming current intervention coverage, the projected HIV incidence in 2021 in Cabo Verde was estimated to be 5.1 per 10,000 person-years (95%CI: 5.0–5.2) in the non-drug using population. Scaling up early HIV treatment and optimization of care and improving condom distribution by 33.3% were the interventions that, when implemented in isolation, resulted in the largest projected decreases in HIV incidence: from 11.5 (95%CI: 10.1–12.9) and 7.7 (95%CI: 6.5–8.9) in 2011 to 3.3 (95%CI: 3.2–3.4) and 3.2 (95%CI: 3.1–3.3) per 10,000 person-years by year 2021 in the non-drug users population, respectively, when considering the entire population. Prioritizing FSW and PWUD resulted in the greatest projected decreases in HIV incidence per 10,000 person-years in the non-drug users population, when the following interventions were scale-up and implemented in isolation to these groups: early HIV treatment and optimization of care [from 11.4 (95%CI: 10.0–12.8) in 2011 to 4.6 (95%CI: 3.8–5.4) in 2021], and improving condom distribution [from 10.5 (95%CI: 9.3–11.7) in 2011 to 4.4 (95%CI: 3.6–5.2) in 2021]. However, the largest decrease was observed when all strategies were combined, resulting in an HIV incidence of 1.4 (95%CI: 1.36–1.44) and 3.4 (95%CI: 2.8–4.0) per 10,000, 72.6% and 33.3% less than the status quo scenario, when considering entire population and prioritizing FSW and PWUD, respectively, see Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Projected HIV incidence (per 10,000 person-years) in 2021 among the non-drug users adult Cabo Verde population, female sex workers, and the drug-using populations, for various scenarios, when covering the entire population (Panel A) and prioritizing female sex workers and people who use drugs (Panel b)

From left to right: Status Quo; increasing substance abuse treatment by 100%; increasing HIV testing by 100%; scaling up early HIV treatment by 100% and optimization of care (by decreasing the rate of ART discontinuation by 50% and improving adherence to ART by 33.3%); increasing condom use by 33.3%; combo prevention

Abbreviations: FSW – female sex workers; HIV – human immunodeficiency virus; PWUD – people who use drugs; SA – substance abuse; Dashed line indicates “HIV elimination phase” (less than 10 cases per 10,000 per year), as defined by Granich et al. (2009)

Among drug-using agents, when substance abuse treatment was increased by 100%, the HIV incidence per 10,000 person-years among PWUD in 2021 was slightly lower than that obtained from the status quo scenario (26.0 and 27.7 per 10,000 person-years, respectively). Scaling up early HIV treatment and optimization of care and improving condom distribution were the intervention strategies that resulted in greater decreases in HIV incidence by year 2021 in the PWUD population: to 19.5 (95%CI: 18.8–20.2) and 17.2 (95%CI: 16.7–17.7) per 10,000, respectively. The individual-based model predicted that the most effective intervention strategy for the PWUD population was the “combination prevention” scenario, resulting in an HIV incidence of 8.2 (95%CI: 7.8–8.6) and 10.7 (95%CI: 6.2–15.2) per 10,000 in year 2021, when considering entire population and prioritizing FSW and PWUD, respectively. Similar results were obtained for FSW that are also PWUD, with an estimated HIV incidence of 6.7 (95%CI: 6.3–7.1) and 7.3 (95%CI: 6.7–7.9) per 10,000 in year 2021, for the “combination prevention” scenario, when considering entire population and prioritizing FSW and PWUD, respectively, see Figure 2.

DISCUSSION

Model findings and interpretation

In this study, we found that early HIV treatment and optimization of care and condom distribution were interventions that resulted in the largest decrease in HIV incidence over a 10-year period (2011 to 2021) in Cabo Verde. Scaling up HIV testing and substance abuse treatment, in the absence of other interventions, were the strategies that had the least impact in reducing the HIV incidence by 2021. Broadly, these results support the UNAIDS/WHO July 2010 guideline revision (WHO 2010), which encourages scaling up earlier initiation of ART to subsequently reduce the rate of AIDS and non-AIDS mortality, and to prevent HIV transmission in at-risk populations (Cohen et al. 2011; Montaner et al. 2010).

Other mathematical modeling studies have examined HIV transmission dynamics in mixed populations in other settings. For instance, in concentrated Asian epidemics, condom campaigns and sexually transmitted infections interventions that reach the most active sex workers can markedly reduce the size of HIV epidemics (Steen et al. 2014). Expanded ART coverage to adult population in early disease stages was also shown to be more cost-effective than current guidelines in South Africa (Alistar et al. 2014). Studies conducted in other African settings have also highlighted the importance of improving access to ART in order to improve and prolong the lives of HIV-positive people and to reduce HIV transmission at the population-level (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2013).

In contrast to other sub-Saharan African countries, Cabo Verde has been successfully able to implement large-scale condom distribution throughout the nation (INE et al. 2008; Tavares et al. 2012; UNAIDS 2012). Previously conducted studies have shown that the majority of Cabo Verde adolescents have access to sexual health information and other sexual transmission disease prevention and contraceptive methods, including condoms (Tavares et al. 2012). The results of our study suggest that policies and programs be developed to ensure sufficient access to condoms among populations particularly vulnerable to HIV, including sex workers and people who use drugs.

We observed that the most significant decrease in HIV incidence occurred when all the interventions are scaled up simultaneously, which resulted in an incidence that could drive to an “elimination phase” of HIV. We also found substantial reductions in HIV incidence when prioritizing FSW and PWUD for condom distribution. In fact, the model predicted that doing so would result in an HIV incidence of less than 10 new cases per 10,000 per year among FSW who are also non-drug users, and close to the threshold for elimination among other groups at risk. These results are in accordance with the “2011-2015 III Strategic Plan to Fight AIDS” that has been implemented by DOHCV/PNLS/CCS-SIDA with support from WHO/UNAIDS and by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, in order to reduce HIV transmission among at-risk groups (i.e.: PWUD and FSW) and in the non-drug users population. Our results also support similar conclusions of other studies that promote combination intervention strategies to reduce or eliminate HIV transmission (Kurth et al. 2011; Marshall et al. 2012; Padian et al. 2011; Piot et al. 2008; Vermund and Hayes 2013).

Model strengths and limitations

Our study is subject to a number of important limitations. First, the individual-based model was adapted from a previously developed and calibrated model to address HIV-1 transmission only, which is transmitted more efficiently than HIV-2 and causes the development of AIDS more rapidly. Even though HIV-2 has circulated in the Cabo Verde population for some time, the prevalence of this strain has been in decline, and HIV-1 has been the dominant type of HIV over the past decade. Therefore, we do not believe that a model in which parameters specific to HIV-2 transmission and disease progression were incorporated would result in meaningfully different results. However, the fact that the ABM only represents HIV-1 transmission limited our ability to calibrate the model based on previously collected HIV incidence data. Thus, our model was not able reproduce the epidemic observed historically in Cabo Verde, as we parameterized the model for HIV-1 transmission only and design the simulation to represent the time period from 2010 onwards.

Second, we did not address mother-to-child-transmission (MTCT) in the individual-based model, but only heterosexual transmission, which represents more than 80% of the HIV transmission in Cabo Verde. In 2009, the HIV incidence among pregnant women was estimated as 0.6% (Lopes 2010), and given the introduction of ART, and other programs that were embraced to prevent MTCT, recent data from the DOHCV suggests there has been a decline in vertical transmission and currently is accountable for 2-3% of all new HIV infections. In future work, the model will incorporate MTCT of HIV. In this case it will be motivating to account for the impact of scaling up HIV testing among pregnant women in decreasing HIV incidence in children.

Third, HIV transmission among MSM was not included in this model. The WHO/UNAIDS has pointed out the necessity to conduct a survey among MSM in Cabo Verde to better understand the epidemiology of HIV in this population. In 2013, the national association of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) was founded in the second largest city of Cabo Verde, Mindelo. The DOHCV/UNAIDS is currently working closely with the LGBT association to conduct a survey of HIV prevalence among MSM. In future work, we hope to incorporate sexual orientation and account for HIV transmission among MSM in Cabo Verde.

Fourth, in sub-Saharan Africa, injection drug use is increasingly common among young adults, and is a growing risk factor for HIV acquisition in the region (Reid 2009). Thus, given the increased prevalence of HIV observed among PWUD in Cabo Verde, it is possible that the introduction of injection modes of drug consumption could result in rapid increases in HIV transmission in this population. The implementation of ongoing drug use surveillance programs to monitor potential increases in injection drug use is recommended. Finally, we recommend that, in addition to the interventions evaluated in this analysis, the DOHCV consider pilot needle and syringe programs in areas of the country most likely to observed increases in injection drug use that could arise over the coming decade.

Fifth, the hypothetical intervention scenarios did not include pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) or post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for HIV negative groups most at risk. Given the potential for PrEP and PEP to reduce the acquisition of HIV infection among sex workers, MSM and people who use and inject drugs (Izulla et al. 2013; Landovitz et al. 2012; Mack et al. 2014; McGowan 2014), future research should be conducted to examine the feasibility of these interventions in this setting.

Sixth, the assumption regarding the relationships between the interventions strategies should be interpreted with caution. For example, we assumed a decrease in risk behaviors occurs following a positive HIV diagnosis, which may not reflect true behavior among all population sub-groups. Furthermore, in the combination prevention strategy, we assumed that the four interventions were scaled up independently of each other, which is likely to be unrealistic.

Seventh, it should be highlighted that 100% correct and consistent condom use is rarely, if ever, observed in sexually active populations; for example, a cohort study of sexually active HIV serodiscordant heterosexual couples with follow-up of the sero-negative partner showed that the proportionate reduction in HIV seroconversion with condom use was approximately 80% (Weller and Davis-Beaty 2002). These efforts should be coupled with behavioral interventions to increase correct and consistent condom use, which includes condom negotiations among populations where gender and power inequalities are highly prevalent skills (Lopez et al. 2013). Therefore, the increased condom distribution scenario should be interpreted with caution.

Eighth, further work is needed to understand the effect of “dual strategy” intervention combinations to better identify which interventions could drive the largest decrease in HIV incidence in specific groups at risk, which could be as effective as the combination of the four interventions, since the substance abuse treatment and HIV testing were the interventions that had relatively low impact in reducing HIV incidence. Potential modeling that seeks to incorporate more heterogeneity (e.g.: having different annual probabilities of unprotected intercourse for primary and secondary partners, incorporate assortative mixing by age group, and a model based on monthly time step), will improve the individual-based model and the capacity to examine targeted intervention strategies. Increasing the number of simulations by 5 to 10 fold would allow a better representation of uncertainty in the outputs given the low prevalence and incidence modeled. We would like to also to point out that, since there is no data available with regards to the sexual and drug-using network patterns in Cabo Verde, we were unable to confirm quantitatively whether the modeled network accurately reflected the real world sexual and drug using network typologies of the population.

Lastly, additional work is required to determine the cost-effectiveness of the different prevention strategies, and which interventions are most cost-effective if integrated in the same facilities. We were unable to conduct cost-effectiveness analyses given that in the condom distribution prevention strategy (and consequently to the combo prevention), condom use was modeled indirectly by scaling down the unprotected intercourse probabilities among different groups in the population. Nevertheless, these results clearly demonstrate the need to dramatically scale-up early treatment and optimization of care and increase condom distribution for FSW and PWUD.

Conclusions and recommendations

In summary, our results show that scaling up all four prevention strategies may dramatically decrease HIV incidence in Cabo Verde among non-drug users, female sex workers, and drug-using populations by the year 2021. We recommend a combination prevention strategy, particularly for populations most at-risk (i.e., female sex workers and people who use drugs), in order to decrease and eventually eliminate HIV transmission in Cabo Verde and other settings characterized by concentrated, overlapping HIV epidemics in key affected groups.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Alistar SS, Grant PM, Bendavid E. Comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy and pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in South Africa. BMC Med. 2014;12(46) doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Differences between HIV-Infected men and women in antiretroviral therapy outcomes - six African countries, 2004-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013 2013 Nov;29(47):62, 945–52. 62(47):945-952. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado APC, Carvalho IAS, Duarte IMS, Andrade VLG. Relatório Estatístico 2012 [2012 Statistical Report] Ministério da Saúde [Department of Health], Praia, República de Cabo Verde [Republic of Cabo Verde. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- DOHCV Relatório Estatístico 2010 [2010 Statistical Report] Minstério da Saúde [Department of Health], Praia, República de Cabo Verde [Republic of Cabo Verde] 2011 [Google Scholar]

- DOHCV Relatório Estatístico 2011 [2011 Statistical Report] Ministério da Saúde [Department of Health], Praia, República de Cabo Verde [Republic of Cabo Verde] 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Downs AM, De Vincenzi I. Probability of heterosexual transmission of HIV: relationship to the number of unprotected sexual contacts. European Study Group in Heterosexual Transmission of HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;11:388–395. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199604010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekouevi DK, Coffie PA, Salou M, et al. HIV seroprevalence among drug users in Togo. Sante Publique. 2013;4:491–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JP, Baeten JM, Lingappa JR, et al. Determinants of per-coital-act HIV-1 infectivity among African HIV-1-serodiscordant couples. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:358–365. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliyasu Z, Abubakar IS, Musa B, Aliyu MH. Post diagnosis reaction, perceived stigma and sexual behaviour of HIV/AIDS patients attending Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Northern Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2011;20(1):135–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IVº RECENSEAMENTO GERAL DA POPULAÇÃO E DE HABITAÇÃO - CENSO 2010 [IVth GENERAL CENSUS OF POPULATION AND HOUSING - 2010 Census] Instituto Nacional de Estatística de Cabo Verde (INE) [National Statistics Institute of Cabo Verde] 2010 http://www.ine.cv. Accessed May 14, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- INE, Ministério da Saúde, Macro International . Instituto Nacional de Estatística de Cabo Verde (INE) [National Statistics Institute of Cabo Verde] Calverton; Maryland, USA: 2008. Segundo Inquérito Demográfico e de Saúde Reprodutiva, Cabo Verde, IDSR-II, 2005 [Second Demographic and Reproductive Health Survey, Cabo Verde, IDSR-II, 2005] [Google Scholar]

- Izulla P, McKinnon LR, Munyao J, et al. HIV postexposure prophylaxis in an urban population of female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(2):220–225. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318278ba1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth AE, Celum C, Baeten JM, Vermund SH, Wasserheit JN. Combination HIV prevention: significance, challenges, and opportunities. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8(1):62–72. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0063-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landovitz RJ, Fletcher JB, Inzhakova G, Lake JE, Shoptaw S, Reback CJ. A novel combination HIV prevention strategy: post-exposure prophylaxis with contingency management for substance abuse treatment among methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(6):320–328. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, Forman V, Knowlton A, Sherman S. Norms, social networks, and HIV-related risk behaviors among urban disadvantaged drug users. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(3):465–476. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- III Congresso da CPLP VIH/SIDA - IST [III CPLP Conference in HIV/AIDS - STD] Lisbon, Portugal: Mar 17-19, 2010. Lopes E Prevenção da Transmissão Vertical do VIH em Cabo Verde [Preventing HIV Vertical Transmission in Cabo Verde] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez LM, Otterness C, Chen M, Steiner M, Gallo MF. Behavioral interventions for improving condom use for dual protection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010662.pub2. 10:CD010662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack N, Odhiambo J, Wong CM, Agot K. Barriers and facilitators to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) eligibility screening and ongoing HIV testing among target populations in Bondo and Rarieda, Kenya: Results of a consultation with community stakeholders. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(231) doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BDL, Friedman SR, Monteiro JFG, et al. Prevention and Treatment Produced Large Decreases in HIV Incidence In A Model Of People Who Inject Drugs. Health Affairs. 2014;33(3):401–409. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BDL, Paczkowski MM, Seemann L, et al. A complex systems approach to evaluate HIV prevention in metropolitan areas: Preliminary implications for combination intervention strategies. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e44833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan I. An Overview of Antiretroviral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis of HIV Infection. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;71(6):624–630. doi: 10.1111/aji.12225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner JS, Lima VD, Barrios R, et al. Association of highly active antiretroviral therapy coverage, population viral load, and yearly new HIV diagnoses in British Columbia, Canada: a population-based study. Lancet. 2010;376:532–539. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60936-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro ML, Sylva RC. Estudo Socio-comportamental e de seroprevalência do VIH/SIDA nos usários de droga/usários de drogas injectável [Socio-behavioral and seroprevalence study of HIV/AIDS in drug users tand injecting drug users] Minstério da Saúde [Department of Health], Praia, República de Cabo Verde [Republic of Cabo Verde] 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Padian NS, McCoy SI, Karim SS, et al. HIV prevention transformed: the new prevention research agenda. Lancet. 2011;378:269–278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60877-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papworth E, Ceesay N, An L, et al. Epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers, their clients, men who have sex with men and people who inject drugs in West and Central Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(Suppl 3):18751. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.4.18751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peitzmeier S, Mason K, Ceesay N, et al. A cross-sectional evaluation of the prevalence and associations of HIV among female sex workers in the Gambia. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25(4):244–522. doi: 10.1177/0956462413498858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piot P, Bartos M, Larson H, Zewdie D, Mane P. Coming to terms with complexity: a call to action for HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372(9641):845–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60888-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid SR. Injection drug use, unsafe medical injections, and HIV in Africa: a systematic review. Harm Reduct J. 2009;6(24) doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steen R, Hontelez JA, Veraart A, White RG, de Vlas SJ. Looking upstream to prevent HIV transmission: can interventions with sex workers alter the course of HIV epidemics in Africa as they did in Asia? AIDS. 2014;28(6):891–899. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylva RC, Semedo E, Monteiro ML. Cartografia e estudo socio-comportamental e de seroprevalência do VIH/SIDA nas profissionais do sexo [Cartography and socio-behavioral and seroprevalence of HIV/AIDS study among sex workers] Minstério da Saúde [Department of Health], Praia, República de Cabo Verde [Republic of Cabo Verde] 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Tavares CM, Schor N, Valenti VE, Kanikadan PYS, Abreu LC. Condom use at last sexual relationship among adolescents of Santiago Island, Cape Verde - West Africa. Reprod Health. 2012;9(29):PMC3538512. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS Rapport d’activite sur la riposte au SIDA au Cap Vert [Progress report on the response to AIDS in Cabo Verde] Comité de coordenação do combate à SIDA [Coordination Committee for the Fight Against AIDS], República de Cabo Verde [Republic of Cabo Verde] 2012 [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS . WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic; p. 198. [Google Scholar]

- Vermund SH, Hayes RJ. Combination Prevention: New Hope for Stopping the Epidemic. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10(2):169–186. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0155-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuylsteke B, Semdé G, Sika L, et al. HIV and STI prevalence among female sex workers in Côte d'Ivoire: why targeted prevention programs should be continued and strengthened. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32627. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1403–1409. doi: 10.1086/429411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller SC, Davis-Beaty K. Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission (Review) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2002;1:CD003255. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003255. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents. WHO, Geneva: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.