Abstract

Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a ubiquitous pathogen that establishes a life long asymptomatic infection in healthy individuals. Infection of immunesuppressed individuals causes serious illness. Transplant and AIDS patients are highly susceptible to CMV leading to life threatening end organ disease. Another vulnerable population is the developing fetus in utero, where congenital infection can result in surviving newborns with long term developmental problems. There is no vaccine licensed for CMV and current antivirals suffer from complications associated with prolonged treatment. These include drug toxicity and emergence of resistant strains. There is an obvious need for new antivirals. Candidate intervention strategies are tested in controlled pre-clinical animal models but species specificity of HCMV precludes the direct study of the virus in an animal model.

Areas covered

This review explores the current status of CMV antivirals and development of new drugs. This includes the use of animal models and the development of new improved models such as humanized animal CMV and bioluminescent imaging of virus in animals in real time.

Expert Opinion

Various new CMV antivirals are in development, some with greater spectrum of activity against other viruses. Although the greatest need is in the setting of transplant patients there remains an unmet need for a safe antiviral strategy against congenital CMV. This is especially important since an effective CMV vaccine remains an elusive goal. In this capacity greater emphasis should be placed on suitable pre-clinical animal models and greater collaboration between industry and academia.

Keywords: CMV, antiviral, humanized virus, bioluminescence imaging, congenital infection, drug resistance, drug toxicity, UL97, UL54, UL89, guinea pig, mouse, ganciclovir, maribavir

1. Introduction

1.1 CMV Disease

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), human herpesvirus 5 (HHV-5), is one of 8 human herpesviruses (Table 1). HCMV is a ubiquitous pathogen but the percentage of the population infected with the virus varies between geographic location and socioeconomic groups in the developed world. Primary HCMV infection in healthy individuals is usually benign but establishes a lifelong latent infection, where the virus is held in check by the host adaptive immune response (both antibody and T cell mediated). Immunesuppressed populations, such as hematopoietic stem cell and solid organ transplant recipients or AIDS patients, are particularly susceptible to reactivation of the virus which can lead to life-threatening end-organ disease [1]. Additionally, primary infection in these populations can also rapidly lead to similar end organ disease. Congenital HCMV infection of newborns, where the virus crosses the placenta and infects the fetus in utero, is of particular concern in developed countries. Infection of the fetus in utero (approximately 1-2% of live births in the U.S.) can lead to serious symptomatic disease including mental retardation and hearing loss [2-4]. The impact of congenital CMV is greater in the developed world because of the number of CMV negative women of child bearing age and the risk of primary infection during pregnancy which substantially increases the likelihood of congenital infection [5]. Pre-existing immunity to CMV can reduce the chance of congenital CMV by up to 69% in healthy individuals [6]. Consequently, with a high percentage of the population having a seropositive status for CMV, the chances of congenital infection are lower in healthy individuals. In the developed world, congenital HCMV is the second most common cause of mental retardation next to Down's syndrome [7]. Additionally, HCMV related deafness occurs at a greater frequency than that related to Hemophilus influenza infection in the pre-HIB vaccine era [8].

Table 1.

Human herpesviruses

| Virus | Common Name | Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Human herpesvirus 1 (HHV-1) | Herpes simplex type 1 (HSV-1) | Cold sores/ neonate encephalitis |

| Human herpesvirus 2 (HHV-2) | Herpes simplex (HSV-2) | Genital sores/ encephalitis |

| Human herpesvirus 3 (HHV-3) | Varicella Zoster virus (VZV) | Chicken Pox/Shingles |

| Human herpesvirus 4 (HHV-4) | Epstein Bar Virus (EBV) | Mononucleosis/ Cancer |

| Human herpesvirus 5 (HHV-5) | Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) | Immunesuppressed related diseases |

| Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) | HHV-6 | Roseola |

| Human herpesvirus 7 (HHV-7) | HHV-7 | Infection related to HHV-6 |

| Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) | Kaposi's sarcoma (KSHV) | AIDS related cancer |

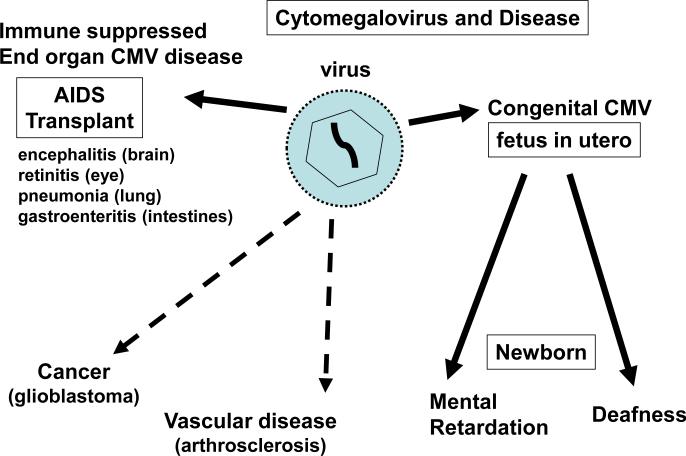

HCMV is also thought to play a role in the development of vascular disease [9, 10] and potentially certain types of cancer [11], both of which are not necessarily associated with an immunesuppressed host. The relationship of CMV to these diseases remains controversial. In the case of vascular disease the demonstrated ability of clinical strains of virus to be truly endothelial tropic and have a specialized mode of entry of endothelial cells via the endocytic pathway certainly strengthens the case [12-16]. As does recent epidemiological studies which strongly suggest that CMV infection may influence the rate of acquired cardiovascular disease and mortality [17, 18]. The link of CMV with specific types of cancer is more tenuous and potentially is via hit and run or bystander effect where an ideal micro-environment for a specific tumor (eg. glioblastoma) is generated. However, the link between HCMV and cancer remains a highly controversial area which might be difficult to demonstrate in an animal model because of HCMV species specificity and limited conserved function by specific gene homologs in the mouse CMV model. Disease associated with HCMV is summarized in Figure 1. Although numerous candidate CMV vaccine strategies are currently under development [19], an effective vaccine, especially one that prevents congenital infection, is a number of years away. Consequently, antivirals are the only available intervention strategy against CMV.

Figure 1. Diseases caused by cytomegalovirus.

Solid line arrows indicate disease directly attributed to viral infection. Dotted lines indicate disease linked to CMV in association with other factors. The link between CMV and certain cancers remains controversial but growing epidemiological data supports a link to cardiovascular disease.

1.2. Virus structure

HCMV belongs to the Betaherpesvirinae genus of the Herpesviridae family and has the largest DNA genome of the eight human herpesviruses. The HCMV genome is 235-45 kb in length and encodes approximately 165 genes [20]. In the virion, a linear copy of the viral genome is encapsidated in an icosahedral protein structure, which is surrounded by a tegument layer of multiple viral proteins necessary for the initial stages of the virus replication cycle. This layer is surrounded by the viral membrane expressing the viral glycoproteins necessary for virus entry into the cell and considered important neutralizing antibody targets (for a more in depth overview of HCMV structure and life cycle see Mocarski and Courcelle [21]). Clinical HCMV isolates are slower growing on human fibroblast cells and differ from laboratory adapted strains of HCMV (e.g. AD169 or Towne) in that they encode additional sequences in the ULb’ locus (about 19kb), which is believed to be associated with viral pathogenicity in man and/or the ability of the virus to grow on epithelial/endothelial cells [12]. This locus is rapidly mutated and deleted in the process of adaptation of the virus to tissue culture fibroblast cells [22]. The UL128-131 genes in the ULb’ locus have been demonstrated to be absolutely necessary for virus entry into epithelial and endothelial cells by a newly identified endocytic method of cell entry that is different from the pathway of infection in fibroblast cells [12-15]. Proteins involved in this endocytic pathway are currently being investigated as novel candidate neutralizing antibody vaccine targets [23, 24].

2. CMV Antivirals and Viral Targets

2.1 Ganciclovir and Viral DNA Replication

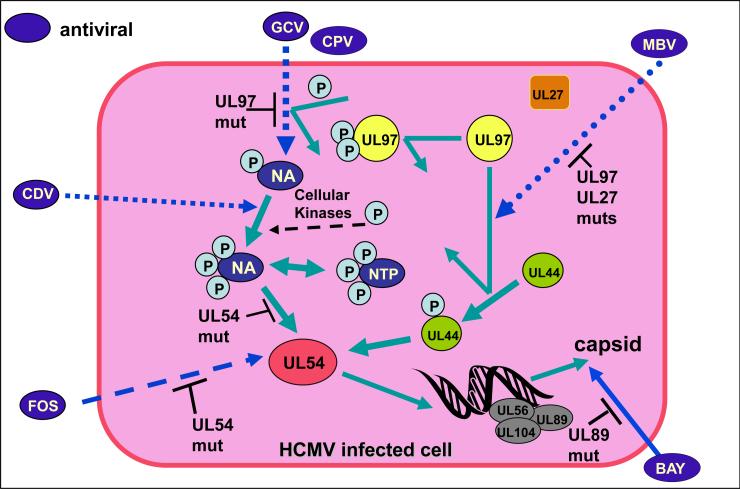

Several antivirals are licensed for the treatment of HCMV infection and mainly function by interfering with viral DNA replication. Figure 2 shows an overview of HCMV antivirals and their viral targets in the infected cell. Ganciclovir (GCV) is the most commonly prescribed HCMV antiviral. GCV was the first drug approved for treatment of HCMV infection and was initially used in the treatment of CMV retinitis in HIV patients (in 1989) but quickly progressed for use in transplant patients [25]. Although HCMV is still a problem in AIDS patients, CMV retinitis is less common in the era of post HAART therapy. GCV is a nucleoside analogue of 2’deoxyguanosine and is converted in a multistep process to ganciclovir triphosphate, the active form of the drug, which competitively inhibits DNA synthesis catalysed by the viral DNA polymerase (UL54 gene). The initial phosphorylation of GCV is catalysed by a viral protein kinase homolog, UL97 [26]. Resistance to GCV arises from mutations in either the UL97 or UL54 gene (reviewed in Gilbert and Boivin [1] and Lurain and Chou [27] and cited papers within references). The majority of the mutations in UL97 are at codons 460 or 520 or clustered in codons 590-607, including a complete deletion from 590-607 and these mutations impair the phosphorylation of GCV and can result in up to a 10 fold decrease in viral drug sensitivity [28-30].

Figure 2. Antivirals against cytomegalovirus and modes of action.

Currently there are 4 antivirals that are used in the clinic for the treatment of CMV (GCV, VGCV, FOS and CDV). GCV is the most commonly used drug and VGCV is a prodrug that can be given orally. Various CMV antiviral under development or currently in use target different aspects of viral DNA synthesis/ packaging in virus infected cells (see text for more details). Mutations in HCMV genes result in resistance to specific antivirals. The antiviral targets are UL97 (viral kinase), viral DNA polymerase (UL54 and UL44 complex) and viral terminase (UL56, UL89 and UL104). Antiviral targets where codon mutations lead to specific drug resistance are indicated as UL97, UL54, UL89, UL44 and UL27. Antivirals under development include MBV, BAY compound (38-4766) and CPV (CDV prodrug). Prodrugs have similar mechanisms of action to their parent drugs once activated but have the advantage of better bioavailability. Other antiviral strategies are mentioned in the text but are not shown (see sections 2 & 3). Figure based on Michel and Mertens (198).

Prolonged treatment with GCV can lead to toxic side effects (neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia) which coupled with the fact that resistant strains emerge, makes GCV use problematic for extended therapy. GCV has been used in a limited capacity as an intervention strategy to prevent hearing loss in HCMV congenitally infected newborns [31]. However, to date no study has been performed in animals to determine if GCV by itself or in combination with another therapeutic strategy is indeed effective in reducing the risk of congenital infection. NIH has conducted clinical trials to determine if GCV therapy is a beneficial treatment for neonates with congenital HCMV infection and CNS sequelae and concluded that the benefits of treatment outweigh the toxic side effects of the intravenous drug therapy [31-34]. GCV is poorly adsorbed from the gastrointestinal tract with total bioavailability of oral GCV being between 5 to 9%. The most common GCV related toxicity in adults is bone marrow suppression, especially neutropenia, occurring in about 40% of patients followed by thromobocytopenia in about 20% of adults treated [35]. In infants, neutropenia has been observed in 34% to 63% of those treated. Other side effects can include anemia, phlebitis and gastrointestinal disturbances. Due to these side effects, certain medications should not be administered with GCV. These include blood dyscrasia causing medications, bone marrow depressants or radiation therapy as concurrent use of these medications can lead to increased bone marrow depressant effects. Nephrotoxic medication (cyclosporine or amphotericin B) and GCV may increase renal functions. The use of zidovudine with GCV has been associated with severe hematologic toxicity and shown to be synergistically cytotoxic. In animal studies GCV was carcinogenic and teratogenic [36] and showed signs of azoospermia leading to possible permanent reproductive toxicity [37]. Additonally, GCV can cause temporary or permanent inhibition of spermatogenesis in men and may suppress fertility in women [38].

In contrast to GCV, the prodrug Valganciclovir, VGC, (a L-valyl ester of GCV) has oral bioavailability which is 10-fold greater than oral GCV and is currently marketed by Roche as “Valcyte”. VGC was approved for use in the clinic in 2000 for AIDS patients and later for transplant patients. In 2009, the USA FDA approved VGC for use in pediatric high risk transplant patients and in Europe there is greater use of VGC as an off label therapy for treatment of children, including congenitally infected babies [38]. Based on animal studies, GCV is potentially carcinogenic but incidence related to GCV clinical trial studies awaits analysis and publication. A pilot survey related to GCV and VGC therapy treatment of children and incidence of cancer is currently underway in Europe (www.ecci.ac.uk).

2.2. Other licensed CMV antivirals

Other antivirals currently approved for treatment for HCMV infection include foscarnet (FOS) and cidofovir (CDV), which inhibit the activity of the viral DNA polymerase (UL54). FOS (phosphonoformic acid) is a pyrophosphate analogue marketed by AstraZeneca as “Foscavir”. This drug binds to the pyrophosphate binding site of the polymerase and causes DNA chain termination. FOS is mainly used to treat patients who failed GCV therapy because of emerging viral resistance to GCV. This drug was first used in the clinic in 1991 and in a comparative study was shown to be as effective as GCV in preventing disease and mortality [39]. Although GCV and FOS have been tested as combination therapy this was determined not to be beneficial [40]. FOS bioavailability is low (<10%) but it has a long half life (48 hours). Most (80%) of the drug is eliminated unmetabolized from the body through the kidney. The other 20% is taken up into the bone and cartilage [41, 42] where it accumulates and remains for months. The most significant toxic side effects of FOS is renal insufficiency, therefore frequent monitoring of renal function is important. Electrolyte abnormalities is another frequent occurrence in those treated with FOS mainly due to hypocalcemia which can lead to seizures. Additionally mucosal damage has also been reported.

Cidofovir (CDV), marketed by Gilead as “Vistide”, is a nucleoside analogue and has a broad-spectrum activity against a number of DNA viruses and functions by causing premature termination of DNA synthesis. Unlike GCV it does not require phosphorylation for activation. Resistant strains of HCMV have been reported under CDV or FOS therapy with mutations in the UL54 DNA polymerase sequence [1, 43-45]. Although FOS drug side effects can result in renal impairment, CDV has more severe side effects that can cause severe renal toxicity and neutropenia limiting its widespread use in treatment against HCMV [46]. A cyclic derivative of CDV, cyclic CDV (cCDV) is less toxic [47]. CDV and cCDV still command a lot of interest because of their antiviral activity against a large number of DNA viruses including the poxviruses and it has been suggested as a front line antiviral against smallpox [48]. However, nephrotoxicity remains an obstacle that would argue against the use of CDV in treatment of CMV infection and was first identified as a potential problem in guinea pigs [49].

Alkoxyalkyl esters of CDV and cCDV have been developed as a way of decreasing toxicity and increasing bioavailability. This approach also resulted in increased antiviral activity against HCMV [50, 51]. One alkoxyalkyl ester of CDV called HDP-CDV (hexadecyloxypropyl-cidofovir) is under development as an oral drug by Chimerix (drug name CMX001) and has up to 4 logs higher level of antiviral activity against HCMV and is effective against CMV in both mouse and guinea pig models [50, 52, 53]. HDP-CDV is currently under a Phase 2 clinical study in stem cell transplant recipients seropositive for CMV. Initial in vitro studies showed increased antiviral activity of HDP-CDV to HCMV with IC50 in nanomolar range (0.9 nM) and an overall increase in antiviral activity of 2-3 logs over CDV [54, 55]. The alkoxyalkyl esterification allows for better absorption from the gastrointestinal tract, increase plasma circulation time leading to infrequent dosing and increased half life. Furthermore, the modified drug showed no signs of nephrotoxicity seen with CDV because the transport mechanisms that caused the accumulation of acyclic nucleoside phosphonates in renal tubular cells do not recognize this drug [56]. In a recent study, HDP-CDV treatment of congenital infection increased pup survival but did not eliminate congenital infection [53]. A group of serine peptide phosphoester prodrugs of cCDV have also been investigated which have better bioavailabilty and activity to HCMV (and poxviruses) with reduced cytotoxicity and improved activity in the rat [57-59]. Overall these recent advances are potentially encouraging for the future development of CDV derivatives.

2.3. Methylenecyclopropane nucleosides

Another group of nucleoside analogs that have potential as HCMV antivirals are methylenecyclopropane nucleosides and among those tested, cyclopropavir (CPV) is most effective with up to 10 fold more activity against HCMV than GCV [60]. Additionally, this drug has been shown to be effective in a hu-SCID animal model [52]. A L-valine ester prodrug of CPV has been developed (valcyclopropavir) which exhibits similar antiviral activity towards HCMV as CPV and studies in mice demonstrated that it had excellent bioavailability [61]. The method of action of both CPV and the prodrug is presumably via pUL97 which phosphorylates the nucleoside analog to its active form and a resistant strain has been isolated by tissue culture passage with a UL97 mutation [62]. Non nucleoside inhibitors of the viral UL54 DNA polymerase have been identified via high through put screening projects [63, 64] but further development of these compounds has not been reported.

2.4. Maribavir

A novel class of HCMV antiviral that has progressed to clinical trials is the riboside analog 1-B-L-ribofuranosyl-2-isopropylamino-5,6-dichlorobenzimidazole or GW1263W94 and is better known as “maribavir” (MBV). This drug manufactured by ViroPharma has antiviral activity that is mediated through the UL97 target protein and could be described as a UL97 kinase inhibitor which blocks the polymerase accessory protein UL44 and assembly of the viral DNA polymerase complex [65-67]. Additionally, the drug inhibits egress of the viral nucleocapsid from the nucleus by presumably interfering with UL97 function [68]. However, the mechanism of action of MBV is not fully understood, insofar as resistant strains generated in the lab have mutations not only in the UL97 gene [29] but also, for some strains, mutations in the UL27, a gene of unknown function [69-71]. Undoubtedly, MBV studies have provided important new insights into pUL97 function.

The most encouraging fact about MBV is that it is effective against CMV strains resistant to GCV, CDV and FOS [72] and additionally lacks toxic side effects associated with other HCMV antivirals [73]. Combined use of GCV and MBV in viral tissue culture studies had an unexpected effect of MBV acting as an antagonist to GCV and increased HCMV IC50 by 13 fold. This problem was not noted in combined use of MBV with FOS or MBV with CDV [74]. MBV was successful in phase II clinical trials of bone marrow transplant patients [75] but a recent phase III clinical trial among allogeneic stem cell transplant patients was disappointing and terminated prematurely [76]. In a case by case basis MBV has been shown to be effective at controlling GCV and FOS resistant strains of HCMV in patients [77]. Perhaps a potential future role for MBV in the clinic will be one of a reserve therapy strategy for patients with resistant strains of HCMV that have arisen via GCV, FOS or CDV therapy.

2.5. Other UL97 mediated CMV antivirals

Other chemical classes of UL97 kinase inhibitors have been identified such as indolocarbozoles and quinazoline derivatives [78, 79, 197] but these have not gone forward to clinical trials. Acyclovir (ACV), 9-(2-hydroxyethooxymethyl)-guanine, is an analog derivative of 2’-deoxyguanosine and requires phophorylation in the cell to become active, as is the case of GCV, and mutants arise by mutations in the UL97 and UL54 genes. Valacyclovir (VCV) is a derivative of ACV with better bioavailability, 68% greater [80]. Both drugs are effective for herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection and lack severe side effects. Unfortunately, both drugs are ineffective in the treatment of established HCMV disease and can only be used in pre-emptive therapy against HCMV.

2.6. Antivirals targeting the CMV DNA terminase complex

Antivirals that target the viral DNA terminase cleavage complex associated with DNA packaging (UL56 and UL89 gene products) have been identified (see figure 2). The advantage of this drug target is that it blocks viral maturation. The initial group of compounds include 2-bromo-5,6-dichloro-1beta-D-ribofuranosyl benzimidazole (BDCRB) and GW-275175X, a ribopyranosyl analog of BDCRB and tomeglovir (BAY-384766), a non-nucleosidic 4-sulfonamide-substituted naphthalene derivative [65, 81-83]. BAY 38-4766 is effective against strains resistant to currently approved HCMV antivirals [84]. Resistant HCMV strains can emerge with mutations in the UL89 coding sequence making a long term strategy against the viral terminase less attractive as first originally thought. However, the alternative method of action of the viral DNA terminase targeting antivirals could potentially allow for a more effective antiviral therapy when used in conjunction with GCV to reduce the likelihood of emerging resistant strains of HCMV. BAY-384766 has not moved forward in clinical trials despite encouraging results in animals (mouse and guinea pigs). Development of BDCRB as an antiviral was halted because of its metabolic cleavage in animal models (mouse and rat). GW-275175X functions in a similar fashion to BDCRB and resistant strains were identified with mutations in UL89 or UL56 [85]. MBV was selected in preference to GW-275175X to move forward to clinical trials.

2.7. High through put screening and other new antivirals

High through put screening of derivatives of 3,4-dihydro-quinazoline-4-yl-acetic identified AIC246 (C29H28F4N4O4) as a novel antiviral, which is currently in phase II clinical trials [86]. This compound has low toxicity in tissue culture and in a xenograft mouse model was more effective than VGCV in treatment of HCMV. The mode of action of this compound is different to GCV and GCV resistant strains are sensitive to this compound [86]. Preliminary studies indicate that it has a similar method of action as BAY38-4766 by blocking cleavage and packaging of viral DNA. However, further studies are necessary to fully identify the mode of action. Two new benzimidazole D-ribonucleosides compounds have also been identified as effective inhibitors targeting the viral terminase, 2-bromo-4,5,6-trichloro-1-(2,3,5-tri-O-acetyl-β-D-ribofuranosyl) benzimidazole (BTCRB) and 2,4,5,6-tetrachloro-1-(2,3,5-tri-O-acetyl-β-D-ribofuranosyl) benzimidazole (Cl4RB) and encouragingly they are effective against murine and rat CMV [87, 88]. C14RB would appear to be more effective than BTCRB, which is more equivalent to BDCRB in HCMV plaque reduction assays. Identification of new antivirals against the viral terminase complex reinforces this as an important drug target but the ability of CMV to become resistant to various terminase complex antivirals means that in the clinic there is potential for resistant strain end organ disease.

3. Alternative antiviral strategies against CMV

3.1. RNAi

Other alternate antiviral strategies have received increased attention because of the recurrent problem of emerging resistant strains. One approach to antiviral design is the use of a 21 bp oligo (antisense to IE1 mRNA) which is licensed as “Fomivirsen” for the treatment of CMV retinitis by direct treatment of the eye, but only as a second line therapy [89]. However, this does demonstrate potential for the future use of RNAi therapeutics against CMV. RNAi antiviral strategy has been investigated with siRNA that targets the UL54 DNA polymerase gene [90]. The DNA polymerase accessory gene UL44 homolog is an effective siRNA target in guinea pig cytomegalovirus (McGregor, unpublished data). Ribozyme antivirals have also been developed against HCMV [91]. A RNaseP ribozyme that targets the nucleocapsid scaffold protease gene (UL80) is effective against HCMV and in the murine cytomegalovirus model [92, 93]. Potentially, a ribozyme antiviral strategy may be more effective than siRNA/shRNA strategies but in both cases the method for effective delivery to the site of infection in the body is poorly developed and remains a problem associated with RNAi therapy.

3.2 Peptide based CMV antivirals

Other strategies against the viral polymerase protein complex have included approaches to disrupt the interaction of the viral DNA polymerase protein (pUL54) and the DNA accessory protein (pUL44). A peptide of the last 22 amino acids of the C-terminal of pUL54 was sufficient to disrupt interactions between pUL54 and pUL44 [94]. Subsequently, high through put screening resulted in the identification of a series of small molecules that specifically disrupt the pUL44 and pUL54 interactions [95]. An advantage of these small compounds is that they bind to regions of the viral polymerase that is different from the nucleoside analogs and consequently could be effective against GCV, CDV and FOS resistant strains of HCMV. Given the conserved nature of CMV viral polymerase (UL54 polymerase and UL44 accessory protein) these small molecules may also be effective antivirals against various animal CMV which would enable testing of these drugs in a pre-clinical animal model. However, the toxicity of these molecules may be more problematic in animals based on initial studies in human tissue [95].

Characterization of HCMV protein functions has resulted in the identification of a viral protein peptide domain that is being explored as a novel antiviral strategy. The transdominant inhibitory effect of the HCMV UL84 protein on virus growth was first identified by Gebert et al. [96], where expression of this protein in a cell line impaired virus production. Since UL84 protein interacts with the trans-activating immediate early protein, IE2, as part of this inhibitory activity [97] this could potentially impair the establishment of resistant strains associated with other drug strategies that target later stages of the virus life cycle. The UL84 protein is also necessary for viral DNA replication and blocking of this function could also have a potent antiviral effect [97]. In HCMV, a UL84 based peptide antiviral strategy has been explored based on the protein NLS sequence [98]. In GPCMV, the transdominant inhibitory domain of the UL84 homolog protein has been narrowed down to a 99 amino acid sequence making it more feasible that a small molecule mimicking the inhibitory domain can be identified [99].

An additional novel peptide strategy has been the development of oligomers of beta amino acids as a means of preventing viral cell fusion and hence entry into the cell by targeting critical regions of the glycoprotein gB and gH alpha helical regions [100]. The inhibitory peptide being beta peptides are relatively resistant to protease degradation which in theory makes them better candidates for testing in an animal model or phase I clinical trials compared to the viral polymerase peptide antiviral.

3.3 Thymidine kinase antivirals and CMV

The antiviral activity of closely related molecules has not yet been investigated but could potentially have greater activity against HCMV. The ability of the thymidine kinase (TK) of orthopoxviruses to use certain thymidine analogs which are not substrates of cellular thymidine kinases has led to the testing of these analogs as herpesvirus antivirals because of overlapping specificities of TK between these families of viruses. A series of 2’-deoxy-4-thiopyrimidine nucleosides were identified as having activity against HCMV [101] and in a more updated screening lead to the identification of 5-iodo-4’-thio-2’deoxyuridine (4’-thioIDU) as having activity against poxviruses and herpesviruses, HCMV, HSV and VZV but not EBV, HHV-6 or HHV-8 [68]. The ability of this compound to inhibit such a large range of viruses merits further study of this antiviral in animal models.

3.4. CMV Passive antibody therapy and congenital infection

In terms of strategies aimed at preventing congenital HCMV infection one approach that has received a relatively high profile is the use of hyper-immune globulin therapy. An anti-HCMV immune globulin formulation has been successfully employed in preventing congenital CMV infection in an uncontrolled human trial [102, 103]. Given the lack of controlled animal studies comparing therapeutic strategies, it is difficult to be certain that this is the best possible intervention strategy for preventing congenital CMV infection. Additionally, at the time of the original study the implications of identifying the novel endocytic pathway of virus entry into epithelial and endothelial cells [13, 14] had not been fully realized in the context of hyperimmune therapy. Therefore the level of neutralizing antibody against components of the endocytic pathway had not been investigated but this aspect is important for neutralizing virus infection of epithelial and endothelial cells [104, 105]. Potential variability in neutralizing capability against the endocytic pathway of cell entry could exist between batches of hyper-immune globulin. This has important implications for neutralizing transplacental infection based on the structure of the placenta. The supplementing of passive antibody therapy with human monoclonals directed against the HCMV endocytic complex [23] is a potential strategy for improving this therapy but an investigation of this strategy in a controlled pre-clinical animal model is merited.

3.5. CMV and Off Label Drug Therapy

Drugs approved for treatment of other diseases have been reported to have anti-CMV effects. However, these observations were made in patients with other underlying conditions or whose HCMV strains are multi-resistant and preclude the use of approved antivirals. Leflunomide is a pyrimidine synthesis inhibitor currently marketed for use in rheumatoid arthritis [106]. Oral bioavailability is as high as 80% and the half life is almost 2 weeks. A major side effect of leflunomide is liver toxicity, therefore special precautions are required when co-administered with other medications to limit added complications. Artesunate is an anti-malarial drug which has been shown to have anti-CMV activity [107]. In one reported case a stem cell transplant recipient who was given Artesunate resulted in a 2 log decrease in viral load in the peripheral blood [27]. Immunosuppressive agents, sirolimus (rapamycin) and its derivative everolimus, not only reduced incidence of HCMV infection in solid organ transplant recipients [108, 109] and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell recipients (Marty et al., 2007) but also have been shown to reduce the viral load in patients infected with GCV resistant HCMV. Drugs with both immunosuppressive and antiviral effects could be therapeutically advantageous, especially in transplant recipients; however, the mechanism behind the anti-CMV activity of rapamycin is not fully understood.

4. CMV Antivirals and Animal Models

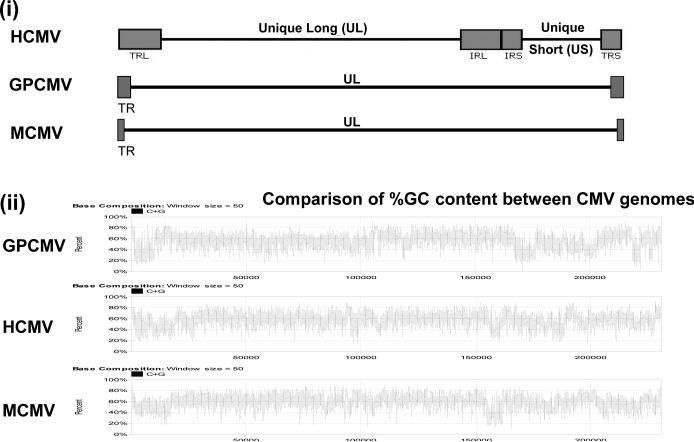

The strict species specificity of HCMV precludes studying this virus in an animal model. Consequently, animal CMVs have been used to investigate intervention strategies in their respective hosts, including rhesus macaque (RhCMV), mouse (MCMV), rat (RCMV), and guinea pig (GPCMV). The genomes of the various animal CMV have been sequenced [110-115]. Figure 3 shows a comparison of the structures of MCMV and GPCMV against HCMV. All animal CMV viral genomes are roughly similar in size but HCMV has a unique long and unique short region flanked by terminal repeats. The rodent animal CMVs have a unique long region flanked by terminal repeats. The significance of the HCMV genomic structure is unknown but is similarly found in other human herpesviruses. Animal CMV exhibit blocks of conservation with HCMV with direct homologs to genes encoded by the HCMV UL region and include the homolog antiviral targets. Regions at the 5’ or 3’ ends of the UL region in animal CMVs tend to encode genes related to the species specific virus survival in their respective host.

Figure 3. Viral genome structure of human and animal cytomegalovirus.

(i) Comparative genome structures of HCMV, mouse (MCMV) and guinea pig (GPCMV) cytomegalovirus. (ii) Comparative % G+C content along the length of HCMV, MCMV and GPCMV.

The recent identification of differences between clinical and lab strains of HCMV [20, 116] has prompted a re-investigation of the stability of animal CMV genomes in the tissue culture compared to in the animal host. The MCMV genome appears relatively stable in both tissue culture and animals [115]. The RhCMV genome undergoes modifications similar to HCMV upon passage on fibroblast cells which results in mutations that impair virus infection of epithelial cells [110, 117-119]. A homolog locus to UL128-131 has recently been identified in elite primary ATCC stock of GPCMV, strain 22122, [114] and this locus is identical in virulent virus retrieved from salivary gland of guinea pigs (McGregor, unpublished data). This locus is unstable in salivary gland virus passaged on fibroblast cells in tissue culture resulting in a virus deleted in this locus with impaired pathogenicity in vivo [120]; McGregor, unpublished observation). Proteins encoded in the UL128-131 locus are currently being investigated as novel HCMV vaccine targets against endo/epithelial tropism [24, 121] and the identification of homologs in animal CMV allows an extension of these studies in pre-clinical animal models.

The various CMV animal models have aided both in the development of current licensed HCMV antivirals and identification of potential toxicity problems associated with different drugs. The mouse model is perhaps the most commonly used because of the low cost and availability of reagents. However, no animal model perfectly duplicates the human infection. Furthermore, there is variation in drug sensitivity of HCMV compared to various animal CMV which also complicates pre-clinical animal model studies. Indeed, some prospective antivirals that are effective against HCMV do not work against animal CMV. This section provides an overview of CMV animal models with recent advancements in specific models. The main focus of this section is the guinea pig and recent novel strategies in the development of this model. Importantly, the guinea pig is the only small animal model that allows the study of congenital CMV infection, as well as general systemic disease. The authors currently use this model in vaccine and antiviral intervention strategies against CMV. A comprehensive retrospective review of the role of animal models in CMV antiviral development is provided by Kern [122].

4.1. Mouse CMV

Mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV) allows the study of the systemic disease in immune competent or immunesuppressed mouse animal models and has been successfully employed in the development of a number of antiviral drugs [122]. Two strains of MCMV are commonly used (K181 and Smith) and both strains have been sequenced [111, 115, 123] but the sequence of field isolates have also been investigated [124]. All strains encode a similar array of genes but are genetically distinct. Infectious BAC clones of both K181 and Smith strains have been developed [123, 125] which allows the easy manipulation of the viral genome.

The mouse continues to be the first animal model of choice for testing new CMV antivirals in vivo. The well defined immune system, availability of multiple transgenic strains, microarray chips and relative inexpensive cost makes this model very attractive. It should be noted that certain strains of mice (eg. C57BL/6) are inherently resistant to MCMV because of a cross reacting antigen of MCMV (m157) which acts as a ligand for Ly49H NK cell receptor activation [126, 127]. This inherent resistance of some strains can be overcome by the knockout of the MCMV m157 gene expressing the cross reacting antigen [128]. The BALB/c mouse is susceptible to wild type MCMV and is employed in most studies. The SCID mouse is ideally suited as a model to study CMV viral pathogenicity as well as the testing of the efficacy of antiviral CMV drugs in an immunesuppressed host [129, 130].

One notable advance has been the development of a hu-SCID mouse model, where surgical implanting of human tissue allows the limited study of HCMV in an immunesuppressed mouse model [131-134]. However, the hu-SCID mouse model is difficult to work with and there is potential for variation between labs. A recent innovation of this approach is the use of an artificial surgical gel foam matrix containing HCMV infected human fibroblast cells, which is surgically embedded in the SCID mouse [135]. Potentially, this approach could standardize the model and allow the testing of different human cell lineages and HCMV antiviral therapies. However, problems related to the blood supply to the implant matrix may need to be perfected.

MCMV is susceptible to GCV but unlike HCMV this is not mediated through the UL97 homolog, M97 [136], and it is likely that the drug sensitivity is related to the cellular phosphorylation of GCV. An attempt to humanize MCMV by insertion of UL97 in place of M97 failed to compliment for the loss of the M97 gene [137]. This chimeric virus grew poorly with kinetics similar to a M97 knockout and deletion or substitution of M97 did not affect viral sensitivity to GCV, which implied that MCMV sensitivity is not related to the M97 protein [137, 138]. This setback limits the ability to humanize CMV and make animal studies more relevant to HCMV. In contrast a chimeric UL97 GPCMV does modify viral sensitivity to GCV [139, 140].

MCMV does not cross the placenta [141]. Potentially, this is because the placenta structure is different between human and mouse [142] and also because of the relatively short gestation period (18-20 days). Consequently, vaccine and antiviral strategies against congenital CMV infection cannot be investigated unless a mechanical method of viral in utero infection is used [143]. Neonatal CNS models of MCMV infection have been developed and antibody therapy has been explored in an attempt to reduce brain infection [144-146]. These MCMV CNS models could potentially be expanded to test the efficacy of antivirals in reducing or preventing infection of the brain. Similarly, a recent model for CMV deafness has been developed in the mouse [147] and potentially this could be used for antiviral therapy strategies which are currently studied in the guinea pig.

In the context of future MCMV antiviral studies, an improved method of virus detection would undoubtedly be beneficial. Although real time PCR allows rapid determination of viral load from DNA of extracted animal tissue this is an end point result and does not allow the tracking in real time of virus dissemination in the same animal over time. In this capacity real time bioluminescence imaging of virus dissemination in an animal would be a distinct advantage. Bioluminescence imaging of luciferase reporter gene expression has been successfully employed in various transgenic mouse studies and imaging of luciferase tagged herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) dissemination in the mouse has been reported [148]. A luciferase tagged MCMV has been developed but not applied to antiviral research [149]. A potential problem associated with the luciferase reporter gene in the backdrop of MCMV is that it is unstable when used in the context of a strong promoter which contrasts with the successful use of GFP or lacZ in MCMV (McGregor, unpublished data; [150-152]).

MCMV is susceptible to GCV but the virus susceptibility to the drug unlike HCMV is not mediated through the UL97 homolog, M97 [136] and it is likely that the drug sensitivity is related to the cellular phosphorylation of GCV. An attempt to humanize MCMV by insertion of UL97 in place of M97 failed to compliment for the loss of the M97 gene [137]. This chimeric virus grew poorly with kinetics similar to a M97 knockout and deletion or substitution of M97 did not affect viral sensitivity to GCV, which implied that MCMV sensitivity is not related to the M97 protein [137, 138].

4.2. Rat CMV and Rhesus Macaque CMV

Rat CMV (RCMV) and rat model have been successfully used in antiviral studies since the 1990s [122]. The Maastricht strain of RCMV has been sequenced and the array of genes is very similar to MCMV [113, 115]. Although RCMV is still used in antiviral research, the RCMV model has progressed towards use in the study of CMV vascular disease such as atherosclerosis and transplant restenosis [10]. Potentially, this model in the future may be useful in the testing of CMV antivirals that are specifically aimed at preventing CMV associated vascular disease and/or limiting rejection of transplant organs due to CMV infection. Although the RCMV genome has been defined there is no infectious BAC clone of RCMV. The generation of such a reagent would undoubtedly ease the process of generation of mutants or recombinant viruses carrying reporter genes for better development of the model and more effective evaluation of antiviral studies.

The rhesus macaque animal model despite being the closest to human infection is not used in antiviral CMV therapy because of the expense as well as the lack of available numbers of CMV negative animals [153]. In theory this animal model could be used in CMV studies since susceptibility to CMV antivirals is noted [154, 155]. The viral genome sequence is established [110, 117] and an infectious BAC clone is available [156]. The recent advances in rhesus macaque immunology and RhCMV virology make this a promising model for future vaccine studies [157, 158]. Importantly, the homolog UL128-131 locus related to the epithelial and endothelial cell infection has been identified which will allow development of novel vaccine strategies against epi/endothelial tropism and potentially congenital infection [110, 117-119].

4.3. Guinea Pig CMV

The guinea pig is an established animal model for a number of pathogens [159, 160] and the animal genome has recently been sequenced (6.79x coverage) by the Broad Institute and annotated (http://uswest.ensembl.org/Cavia_porcellus/Info/Index). Consequently, many reagents not previously available for the guinea pig can now be developed, which should help in the development of the guinea pig model for a number of pathogens including CMV. The guinea pig is uniquely useful for the study of congenital CMV infection [161-163], presumably because of the similarity of structure between the guinea pig and human placenta. Both human and guinea pig placentas are hemomonochorial containing a homogenous layer of endothelial trophoblast cells separating maternal and fetal circulation [161, 164, 165]. Furthermore, the gestation period (approximately 70 days) in the guinea pig is broken up into three trimesters as is human pregnancy which makes this model ideally suited for testing of intervention strategies against congenital CMV infection. Virus challenge studies are usually performed at late second trimester to early third trimester to maximize congenital infection which results in a transmission rate of up to 75% when salivary gland derived virus stocks are used. The virus strain 22122 was originally isolated form outbred guinea pigs [166]. The majority of animal studies are conducted with outbred Hartley guinea pigs but studies have been performed with inbred strain 2 animals. Hartley guinea pigs are available from commercial vendors but animals have to be screened by ELISA to verify that they are negative for the guinea pig CMV (GPCMV) prior to any studies. Although useful for congenital CMV studies, the guinea pig has also proved a useful model for the study of systemic disease in adults and neonates [46]. An immunesuppressed model has been developed via the administration of cylophosphamide, which temporarily suppresses the host immune system in a similar fashion to immunesuppressed transplant patients [167].

Congenital GPCMV causes disease similar to human infection in newborn pups, including deafness [168, 169]. Additionally, hearing loss can also be induced by direct injection of virus into the cochlea [170, 171]. Both FOS and cCDV are effective in treating GPCMV systemic infection [122, 172]. Furthermore, cCDV prevents or reduces the rate of congenital infection [173, 174] as well as hearing loss in the guinea pig [171]. More recently, another CDV prodrug HPD-CDV, also called CMX001, has been tested in the guinea pig congenital model. This prodrug has the advantage of lower toxicity compared to CDV and has a wide range of antiviral activity to other viruses (herpes, adeno and orthopox) [175, 176]. Oral therapy of GPCMV infected pregnant dams resulted in increased pup survival in treated groups compared to non-treated control group but it did not completely prevent congenital CMV infection as virus could be detected in the tissue of some pups and still births occurred at lower drug dosage [53]. However, these results demonstrate potential for this antiviral especially in the context of congenital infection.

GPCMV is susceptible to terminase antivirals [177, 178]. BAY 38-4766 is effective in both mouse and guinea pig animal models [179, 180] and resistant strains can be isolated that have modifications to the UL89 homolog gene (M89 or GP89). Other more recent CMV terminase antivirals have not been tested in the guinea pig. This is perhaps unsurprising since most antivirals are geared towards systemic disease therapy rather than protection against congenital infection. Therefore studies with these antivirals have been carried out in the mouse.

The approach of using passive antibody therapy to prevent congenital CMV infection has been investigated to a limited extent in the guinea pig model. Studies suggested that anti-GPCMV antibody that targeted viral glycoproteins reduced the incidence of fetal infection by GPCMV, but did not eliminate it [181, 182]. GPCMV encodes direct homologs to HCMV glycoproteins gB, gH, gL, gM, gN and gO [112]. In HCMV these proteins form complexes on the viral membrane: gI (gB); gII (gH, gL, gO); gIII (gM, gN) and these are important neutralizing target antigens [183-185]. In GPCMV, the glycoprotein gB is the immunodominant neutralizing target antigen [186, 187] but based on the conserved essential nature of other GPCMV glycoproteins [188]; McGregor et al., paper in preparation) these too are undoubtedly important neutralizing target antigens. The original passive antibody therapy studies in GPCMV were conducted prior to characterization of viral glycoproteins. Consequently, there is merit in a re-investigation of this strategy, especially with the recent identification of GPCMV gene homologs to HCMV UL128-131 (GP128-131) in ATCC stock or salivary gland derived virus [114]; McGregor, unpublished data) which enhance virus pathogenicity in vivo [120]. This implies that an alternative endocytic pathway of entry into epi/endothelial cells (via gH/gL/UL128-131 homologs) occurs in GPCMV as seen in HCMV [13-15]. However, these studies would by necessity have to define the significance of the endocytic cell entry pathway in congenital CMV infection in the guinea pig model.

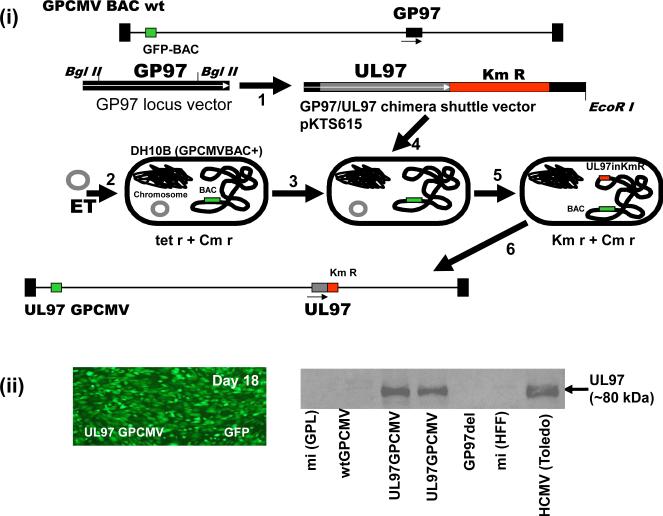

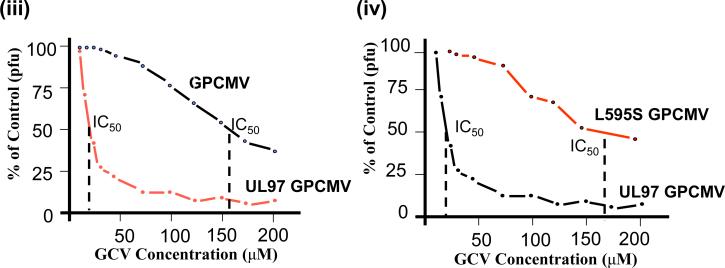

One of the biggest drawbacks with GPCMV has been the lack of sensitivity to some antivirals. Most notably, GPCMV is resistant to GCV and treatment is ineffective in the guinea pig at clinically relevant doses [189, 190]. However, higher dose GCV therapy has been successfully used in preventing CMV related labyrinthitis in guinea pigs [190]. GPCMV is similarly resistant to MBV [178]. Although the methods of action are different for GCV and MBV both antivirals function via the viral kinase UL97 target protein (pUL97). GPCMV encodes a direct homolog to the pUL97 (pGP97), encoded by the GP97 gene [139, 191]. In HCMV, resistance to GCV and MBV is mainly linked to modifications to the pUL97 codon sequence. We hypothesized that pGP97 could be considered to be a highly mutated version of pUL97 which would account for GPCMV resistance to GCV. Therefore potentially, the GP97 coding sequence could be substituted with a UL97 coding sequence in a chimeric GPCMV to enhance virus susceptibility to antivirals targeting the UL97 protein. An infectious GPCMV bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) was modified in bacteria to generate a chimeric GPCMV BAC encoding UL97 in place of the GP97 coding sequence [139]. Figure 4 shows the strategy involved in the generation of a chimeric UL97 GPCMV. Additionally, the GP97 coding sequence was knocked out in another GPCMV BAC to demonstrate an impaired phenotype similar to a HCMV UL97 null mutant [138]. Both the UL97 chimera GPCMV BAC and the GP97 null GPCMV BAC clones were verified as correct and transfected onto tissue culture guinea pig fibroblast cells to generate virus. A green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene encoded in the recombinant viruses enabled the tracking of the virus spread in tissue culture. The UL97 chimera virus spread across the cell monolayer of fibroblast cells and had similar growth kinetics to wild type GPCMV. In contrast, the GP97 knockout mutant was impaired for growth and had a similar phenotype to a HCMV UL97 deletion mutant [138, 139]. Characterization of the chimeric GPCMV verified that it expressed the UL97 protein in virus infected cells and that the virus was capable of phosphorylating the cellular retinoblastoma protein via the viral UL97 kinase (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Generation of UL97 chimeric GPCMV encoding wild type or mutant versions of HCMV UL97.

An infectious GPCMV BAC was modified in bacteria to delete the UL97 homolog gene (GP97) and introduce in place the HCMV UL97 ORF under GP97 promoter control. (i) Mutagenesis of the GPCMV BAC and generation of infectious virus. 1. A GP97 locus shuttle vector was modified by the insertion of the UL97 coding sequence from HCMV Towne strain. Bacteria (DH10B) carrying the GPCMV BAC were modified by introduction of a plasmid encoding red ET recombination to temporally induce recombination positive conditions in bacteria (2 and 3). Linearized UL97 chimeric plasmid shuttle vector is introduced into bacteria (4) and bacterial colonies carrying modified BAC are selected by insertion of kanamycin (Km) drug marker co-inserted into the GP97 locus along with the UL97 coding sequences. Selection is made at a higher temperature (31°C switched 39°C) to remove the ts ET plasmid (5). Chimeric UL97 GPCMV BAC DNA is characterized and subsequently transfected onto guinea pig fibroblast cells (GPL) to generate virus (6). (ii) Left, viral spread across cell monolayer detected by GFP reporter gene expression. Right, western blot analysis of chimeric virus infected cell lysate (UL97GPCMV) or control uninfected cell lysate (mi) vs wild type GPCMV (wt GPCMV) or GP97 deletion mutant (GP97 del) demonstrated a band corresponding to UL97 protein in the chimeric virus infected cell lysate corresponding to a similar sized band in HCMV infected cell lysate.

(iii). GCV antiviral plaque reduction assays of wild type GPCMV and UL97 chimeric GPCMV. Antiviral plaque reduction assay demonstrates that the UL97 chimeric GPCMV has modified susceptibility to antiviral GCV in comparison to wild type GPCMV. Assay was carried out as described in McGregor et al. (2008). The IC50 values of both viruses are indicated. (iv) GCV antiviral plaque reduction assays of wild type and mutant UL97 chimeric GPCMV. A chimeric UL97 GPCMV was generated that contained a common UL97 codon mutation commonly found in GCV resistant HCMV strains. Original chimeric virus (UL97 GPCMV) is sensitive to GCV in contrast the mutant UL97 (L595S GPCMV) chimera (codon 595 change L to S) is resistant to GCV with modified IC50 value compared to wild type chimera.

Analysis of the chimeric virus susceptibility to the GCV antiviral in comparison to that of wild type GPCMV by plaque reduction assay demonstrated that the chimeric virus had increased susceptibility to GCV (Figure 4). The UL97 chimeric virus had a GCV IC50 value that was dramatically different to wild type GPCMV (12.5 μM and over 125 μM respectively), see Figure 4. The chimeric virus susceptibility to GCV is similar to that of clinical strains of HCMV. The chimeric virus susceptibility to MBV was similarly dramatically improved [139]. The UL97 gene was also introduced into the backdrop of a second generation GPCMV BAC [104] which enabled the excision of the original BAC plasmid upon re-generation of virus. This UL97 chimeric virus is currently being used to test the ability of GCV to prevent congenital CMV infection in the guinea pig model. Preliminary studies have demonstrated that GCV was an effective antiviral against the chimeric UL97 GPCMV at clinically relevant dosage in an immunesuppressed guinea pig model [140]. Additionally, the susceptibility to GCV can be modified in chimeric GPCMV by the introduction of common codon changes found in UL97 sequence of GCV resistant strains of HCMV [140]. Figure 4 shows the result for a chimeric UL97 mutant GPCMV where the UL97 coding sequence carries a common UL97 codon change (L595S) that modifies viral sensitivity to GCV. In this case the increased viral resistance is almost 10 fold higher which is similar to that seen for HCMV resistant strains carrying this mutation [1]. This approach allows the ability to look at antiviral strategies that target UL97 in the guinea pig model and additionally the ability to study disease or alternative therapeutic strategies associated with specific resistant strains.

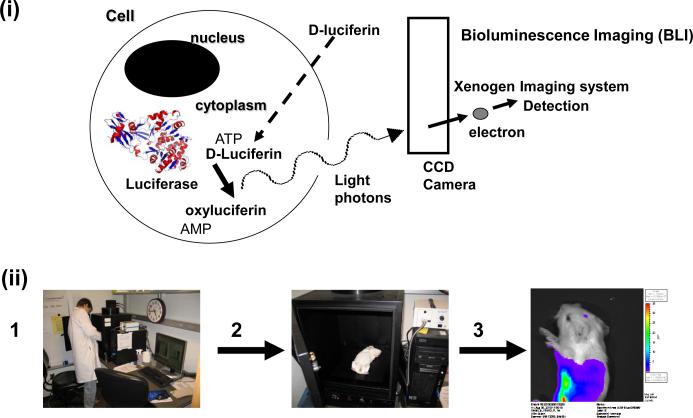

As with other CMV models, detection of virus in target tissue of infected animals is either by co-culture of tissue homogenate (for virus) or by viral load by real time PCR assay of DNA extracted from target tissue (for viral genome copies). These approaches are slow and time consuming and represent end points in studies. Additionally, this approach does not allow the ability to continue to track the progress of virus infection in a single animal in real time. We are currently investigating the ability to track viral dissemination in an animal model by whole animal bioluminescence imaging. In this approach recombinant viruses tagged with luciferase firefly reporter gene can be tracked in real time in the same animal provided the animal is injected with luciferase enzyme substrate (D-luciferin) prior to imaging. Bioluminescence imaging has been successfully employed in mouse animal studies with microbial pathogens tagged with luciferase reporter gene [192]. The bioluminescence imaging strategy for infected animals is shown in Figure 5. In order to generate a luciferase tagged GPCMV a reporter gene under HCMV IE enhancer promoter control was introduced into an intergenic locus between homologs of HCMV UL25 and UL26 genes via BAC mutagenesis. The modified locus was verified as correct and recombinant virus was generated by transfection of the BAC DNA onto guinea pig fibroblast cells. The luciferase tagged virus (designated vGP2526LUC) grew with normal growth kinetics and produced high levels of bioluminescence activity upon infection of fibroblast cells.

Figure 5. Strategy for bioluminescence imaging of virus infected animals.

(i) Bioluminescent signal from cells. Firefly luciferase enzyme expressed in cells acts on specific substrate (D-luciferin) to release light photons which can be detected by a CCD camera above the imaging chamber of the Xenogen/Kalipar imaging apparatus and software enables overlay of detected photon intensity over a still black and white image of the subject.

(ii) Imaging procedure.1. Bioluminescence imaging station (Xenogen IVIS 50). 2. Sedated animal is placed in imaging chamber and imaging acquired over a set period of time (usually 5 min.). 3. Photons emitted from the animal is detected and software converts results into intensity of light emission over a black and white image of the animal. Bioluminescence measured in photons per second per centimeter square per steradian.

(iii) BLI of GPCMV dissemination in the guinea pig. Neonatal guinea pigs infected with recombinant luciferase tagged GPCMV (1× 106 pfu via intraperitoneal route). Virus infection that starts in the spleen progresses to the liver, lungs and eventually to the brain. Bioluminescence image A and B of the same animal from above. A. upper body and head. B. lower torso. C. Two animals side image upper body and head. All images taken at 7 days post infection with 5 min. imaging. Animals injected with 0.2 ml D-luciferin (30 mg/ml) and sedated prior to imaging. Animals were handled following University of Minnesota IACUC guidelines. Highest levels of bioluminescence appear in red as indicated in side bar. Bioluminescence measured in photons per second per centimeter square per steradian.

We investigated the ability to use the luciferase tagged virus in both adult and neonate guinea pigs. Animals infected with virus via intraperitoneal injection (1 × 106 pfu) allowed the tracking of the virus in animals in real time via bioluminescence imaging over a 2 week period. In both adult and neonate guinea pigs, virus disseminated to target organs (spleen, liver, lung) and in neonates virus infection of the brain was also observed by approximately 7 days post infection (Figure 5). These results illustrate the potential of this approach to rapidly determine the extent of viral dissemination in an animal model and consequently allow a more rapid determination of the efficacy of any drug therapy against CMV in the animal model. It was initially thought that the depth of tissue in this animal would reduce the intensity of signal to such a level that a BLI strategy would be impractical in comparison to a smaller animal model. Importantly, the success of the BLI strategy demonstrates that the size of the guinea pig is not a major drawback in comparison to the mouse.

The use of a novel non-invasive imaging strategy for detection of virus dissemination has tremendous potential in aiding the development and evaluation of new therapies against CMV. The coupled approach of novel bioluminescence imaging strategies and humanized GPCMV should not only dramatically increase the relevance of studies in the guinea pig model but also provide novel insights into current and future antiviral strategies in an animal model. Hopefully, the use of these innovative models should provide the basis for determining the efficacy of antiviral strategies in treatment or prevention of congenital CMV infection and neonate CMV infection including sensorineural hearing loss.

5. Expert Opinion / Future Direction

The lack of an effective vaccine against CMV coupled with the emergence of antiviral resistant strains and the toxicity risks associated with prolonged therapy using current antivirals makes the development of new CMV antivirals a necessity. Encouragingly, a number of novel targets and approaches are being explored in CMV antiviral design. However, with the exception of MBV no new drug has recently gone into phase III clinical trials. Perhaps the disappointing results from the MBV phase III trial [76] have diminished enthusiasm for taking forward other candidates. The patent for GCV has recently expired which means that a cheaper generic drug is now available. However, any fundamental problems associated with GCV will also hold true for a generic drug. Many new CMV antivirals under development have a wider range of activity against other viruses. This potentially could lead to more effective treatment of transplant patients by minimizing complications from multi-drug therapy. The potential risk associated with the development of resistant strains of CMV remains an issue associated with many emerging antivirals. Principally this is due to drugs targeting DNA replication or viral DNA packaging at later stages of the virus life cycle, where there is a potential for selective pressure to result in the generation of resistant strains. This obviously occurs with existing therapies and it is one of the reasons for the development of new treatments. There is an additional need for development of drugs that target CMV at an earlier stage to limit the likelihood of resistant strains emerging.

Every year there are approximately 130,000 solid organ and bone marrow transplants performed worldwide [193]. Therefore the greatest CMV antiviral therapy need is for the treatment of these patients where the risk of HCMV disease is highest (up to 32% for kidney transplant; 29% for liver; 41% for lung/heart and lung; 50% for pancreas; and 35% for allogenic bone marrow) [194-196]. However, the risk of congenital CMV infection is also important and can be as high as 50% in seronegative mothers that acquire primary infection during pregnancy [7]. Consequently, there is a need for development of an effective therapy to reduce the chance of congenital disease in a mother diagnosed with an active CMV infection. Passive antibody therapy is perhaps the only current option given the potential side effects and toxicity associated with current antivirals. However, the efficacy of this strategy is still open to debate and should be properly investigated in a controlled animal model that enables the evaluation of the neutralizing response to epithelial/endothelial cells as an aspect of congenital infection.

Currently available or improved animal models coupled with high through put screening tissue culture assays make it practical to rationally design and screen new antivirals for specific CMV diseases. However, for the use of pre-clinical animal models to become more common place there needs to be a more coordinated approach between academia and industry. Although there is an obvious need for better antivirals against CMV, the rate at which drugs enter into clinical trials is relatively disappointing and perhaps a more concerted effort of screening drugs in pre-clinical animal models may aid in the transition. Most certainly an effective vaccine against CMV is still a number of years away and therefore antivirals remain an important priority

Article Highlights.

Cytomegalovirus continues to be a problem of the immunesuppressed.

Existing antivirals have toxic side effects and lead to development of resistant strains.

Various new antivirals are in development some with greater spectrum of activity against other viruses.

New animal models in mice and guinea pigs allow better evaluation of potential therapies.

Specific antiviral strategies against congenital cytomegalovirus infection are poorly explored in comparison to candidate vaccines in animal models.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of interest

Antiviral CMV research in the McGregor lab is funded by grants from the March of Dimes Organization and Minnesota Medical Foundation (MMF). CMV vaccine research is funded by NIH (1R21AI080972-01) and an AHC seed grant from the University of Minnesota.

References

- 1.Gilbert C, Boivin G. Human cytomegalovirus resistance to antiviral drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005 Mar;49(3):873–83. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.3.873-883.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross SA, Boppana SB. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: Outcome and diagnosis. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2005 Jan;16(1):44–9. doi: 10.1053/j.spid.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffiths PD, Walter S. Cytomegalovirus. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005 Jun;18(3):241–5. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000168385.39390.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenneson A, Cannon MJ. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev Med Virol. 2007 Jul-Aug;17(4):253–76. doi: 10.1002/rmv.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colugnati FA, Staras SA, Dollard SC, et al. Incidence of cytomegalovirus infection among the general population and pregnant women in the united states. BMC Infect Dis. 2007 Jul 2;7:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fowler KB, Stagno S, Pass RF. Maternal immunity and prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. JAMA. 2003 Feb 26;289(8):1008–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dollard SC, Grosse SD, Ross DS. New estimates of the prevalence of neurological and sensory sequelae and mortality associated with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol. 2007 Sep-Oct;17(5):355–63. doi: 10.1002/rmv.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pass RF. Immunization strategy for prevention of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Infect Agents Dis. 1996 Oct;5(4):240–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caposio P, Orloff SL, Streblow DN. The role of cytomegalovirus in angiogenesis. Virus Res. 2010 Oct 1; doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Streblow DN, Dumortier J, Moses AV, et al. Mechanisms of cytomegalovirus-accelerated vascular disease: Induction of paracrine factors that promote angiogenesis and wound healing. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:397–415. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soroceanu L, Cobbs CS. Is HCMV a tumor promoter? Virus Res. 2010 Oct 29; doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn G, Revello MG, Patrone M, et al. Human cytomegalovirus UL131-128 genes are indispensable for virus growth in endothelial cells and virus transfer to leukocytes. J Virol. 2004 Sep;78(18):10023–33. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.18.10023-10033.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang D, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus virion protein complex required for epithelial and endothelial cell tropism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005a Dec 13;102(50):18153–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509201102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang D, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus UL131 open reading frame is required for epithelial cell tropism. J Virol. 2005b Aug;79(16):10330–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10330-10338.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryckman BJ, Jarvis MA, Drummond DD, et al. Human cytomegalovirus entry into epithelial and endothelial cells depends on genes UL128 to UL150 and occurs by endocytosis and low-pH fusion. J Virol. 2006 Jan;80(2):710–22. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.710-722.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patrone M, Secchi M, Fiorina L, et al. Human cytomegalovirus UL130 protein promotes endothelial cell infection through a producer cell modification of the virion. J Virol. 2005 Jul;79(13):8361–73. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8361-8373.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simanek AM, Dowd JB, Pawelec G, et al. Seropositivity to cytomegalovirus, inflammation, all-cause and cardiovascular disease-related mortality in the united states. PLoS One. 2011 Feb 17;6(2):e16103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strandberg TE, Pitkala KH, Tilvis RS. Cytomegalovirus antibody level and mortality among community-dwelling older adults with stable cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2009 Jan 28;301(4):380–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sung H, Schleiss MR. Update on the current status of cytomegalovirus vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2010 Nov;9(11):1303–14. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolan A, Cunningham C, Hector RD, et al. Genetic content of wild-type human cytomegalovirus. J Gen Virol. 2004 May;85(Pt 5):1301–12. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.79888-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mocarski ES, Courcelle CT. Cytomegalovirus and their replication. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. 4th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2001. pp. 2629–2673. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dargan DJ, Douglas E, Cunningham C, et al. Sequential mutations associated with adaptation of human cytomegalovirus to growth in cell culture. J Gen Virol. 2010 Jun;91(Pt 6):1535–46. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.018994-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macagno A, Bernasconi NL, Vanzetta F, et al. Isolation of human monoclonal antibodies that potently neutralize human cytomegalovirus infection by targeting different epitopes on the gH/gL/UL128-131A complex. J Virol. 2010 Jan;84(2):1005–13. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01809-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saccoccio FM, Sauer AL, Cui X, et al. Peptides from cytomegalovirus UL130 and UL131 proteins induce high titer antibodies that block viral entry into mucosal epithelial cells. Vaccine. 2011 Mar 24;29(15):2705–11. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Razonable RR, Emery VC. Management of CMV infection and disease in transplant patients. 27-29 february 2004.. Herpes; 11th Annual Meeting of the IHMF (International Herpes Management Forum); Dec, 2004. pp. 77–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan V, Talarico CL, Stanat SC, et al. A protein kinase homologue controls phosphorylation of ganciclovir in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. Nature. 1992 Jul 9;358(6382):162–4. doi: 10.1038/358162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lurain NS, Chou S. Antiviral drug resistance of human cytomegalovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010 Oct;23(4):689–712. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00009-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chou S, Waldemer RH, Senters AE, et al. Cytomegalovirus UL97 phosphotransferase mutations that affect susceptibility to ganciclovir. J Infect Dis. 2002 Jan 15;185(2):162–9. doi: 10.1086/338362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chou S. Cytomegalovirus UL97 mutations in the era of ganciclovir and maribavir. Rev Med Virol. 2008 Jul-Aug;18(4):233–46. doi: 10.1002/rmv.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baldanti F, Michel D, Simoncini L, et al. Mutations in the UL97 ORF of ganciclovir-resistant clinical cytomegalovirus isolates differentially affect GCV phosphorylation as determined in a recombinant vaccinia virus system. Antiviral Res. 2002 Apr;54(1):59–67. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(01)00211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimberlin DW, Lin CY, Sanchez PJ, et al. Effect of ganciclovir therapy on hearing in symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus disease involving the central nervous system: A randomized, controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2003 Jul;143(1):16–25. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(03)00192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitley RJ, Cloud G, Gruber W, et al. Ganciclovir treatment of symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection: Results of a phase II study. national institute of allergy and infectious diseases collaborative antiviral study group. J Infect Dis. 1997 May;175(5):1080–6. doi: 10.1086/516445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradford RD, Cloud G, Lakeman AD, et al. Detection of cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA by polymerase chain reaction is associated with hearing loss in newborns with symptomatic congenital CMV infection involving the central nervous system. J Infect Dis. 2005 Jan 15;191(2):227–33. doi: 10.1086/426456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oliver SE, Cloud GA, Sanchez PJ, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes following ganciclovir therapy in symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infections involving the central nervous system. J Clin Virol. 2009 Dec;46(Suppl 4):S22–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kimberlin DW. Antiviral therapy for cytomegalovirus infections in pediatric patients. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2002 Jan;13(1):22–30. doi: 10.1053/spid.2002.29754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris DJ. Adverse effects and drug interactions of clinical importance with antiviral drugs. Drug Saf. 1994 Apr;10(4):281–91. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199410040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faulds D, Heel RC. Ganciclovir. A review of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy in cytomegalovirus infections. Drugs. 1990 Apr;39(4):597–638. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199039040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharland M, Luck S, Griffiths P, et al. Antiviral therapy of CMV disease in children. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;697:243–60. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7185-2_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reusser P, Einsele H, Lee J, et al. Randomized multicenter trial of foscarnet versus ganciclovir for preemptive therapy of cytomegalovirus infection after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2002 Feb 15;99(4):1159–64. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mattes FM, Hainsworth EG, Geretti AM, et al. A randomized, controlled trial comparing ganciclovir to ganciclovir plus foscarnet (each at half dose) for preemptive therapy of cytomegalovirus infection in transplant recipients. J Infect Dis. 2004 Apr 15;189(8):1355–61. doi: 10.1086/383040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luck S, Sharland M, Griffiths P, et al. Advances in the antiviral therapy of herpes virus infection in children. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2006 Dec;4(6):1005–20. doi: 10.1586/14787210.4.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wagstaff AJ, Bryson HM. Foscarnet. A reappraisal of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in immunocompromised patients with viral infections. Drugs. 1994 Aug;48(2):199–226. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199448020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith IL, Cherrington JM, Jiles RE, et al. High-level resistance of cytomegalovirus to ganciclovir is associated with alterations in both the UL97 and DNA polymerase genes. J Infect Dis. 1997 Jul;176(1):69–77. doi: 10.1086/514041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cihlar T, Fuller MD, Cherrington JM. Characterization of drug resistance-associated mutations in the human cytomegalovirus DNA polymerase gene by using recombinant mutant viruses generated from overlapping DNA fragments. J Virol. 1998 Jul;72(7):5927–36. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5927-5936.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chou S, Lurain NS, Thompson KD, et al. Viral DNA polymerase mutations associated with drug resistance in human cytomegalovirus. J Infect Dis. 2003 Jul 1;188(1):32–9. doi: 10.1086/375743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Biron KK. Antiviral drugs for cytomegalovirus diseases. Antiviral Res. 2006 Sep;71(2-3):154–63. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bischofberger N, Hitchcock MJ, Chen MS, et al. 1- [((S)-2-hydroxy-2-oxo-1,4,2-dioxaphosphorinan-5-yl)methyl] cytosine, an intracellular prodrug for (S)-1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)cytosine with improved therapeutic index in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994 Oct;38(10):2387–91. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.10.2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Clercq E. Cidofovir in the treatment of poxvirus infections. Antiviral Res. 2002 Jul;55(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00008-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bravo FJ, Stanberry LR, Kier AB, et al. Evaluation of HPMPC therapy for primary and recurrent genital herpes in mice and guinea pigs. Antiviral Res. 1993 May;21(1):59–72. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(93)90067-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beadle JR, Hartline C, Aldern KA, et al. Alkoxyalkyl esters of cidofovir and cyclic cidofovir exhibit multiple-log enhancement of antiviral activity against cytomegalovirus and herpesvirus replication in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002 Aug;46(8):2381–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.8.2381-2386.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ciesla SL, Trahan J, Wan WB, et al. Esterification of cidofovir with alkoxyalkanols increases oral bioavailability and diminishes drug accumulation in kidney. Antiviral Res. 2003 Aug;59(3):163–71. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(03)00110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kern ER, Collins DJ, Wan WB, et al. Oral treatment of murine cytomegalovirus infections with ether lipid esters of cidofovir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004 Sep;48(9):3516–22. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.9.3516-3522.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bravo FJ, Bernstein DI, Beadle JR, et al. Oral hexadecyloxypropyl-cidofovir therapy in pregnant guinea pigs improves outcome in the congenital model of cytomegalovirus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011 Jan;55(1):35–41. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00971-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams-Aziz SL, Hartline CB, Harden EA, et al. Comparative activities of lipid esters of cidofovir and cyclic cidofovir against replication of herpesviruses in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005 Sep;49(9):3724–33. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.9.3724-3733.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hartline CB, Gustin KM, Wan WB, et al. Ether lipid-ester prodrugs of acyclic nucleoside phosphonates: Activity against adenovirus replication in vitro. J Infect Dis. 2005 Feb 1;191(3):396–9. doi: 10.1086/426831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hostetler KY. Alkoxyalkyl prodrugs of acyclic nucleoside phosphonates enhance oral antiviral activity and reduce toxicity: Current state of the art. Antiviral Res. 2009 May;82(2):A84–98. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eriksson U, Peterson LW, Kashemirov BA, et al. Serine peptide phosphoester prodrugs of cyclic cidofovir: Synthesis, transport, and antiviral activity. Mol Pharm. 2008 Jul-Aug;5(4):598–609. doi: 10.1021/mp8000099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]