Abstract

Background

Little is known about the rate at which cancer survivors successfully adopt a child or about their experiences negotiating a costly, and perhaps discriminatory, process regarding the prospective parent's health history. The current study describes the results of a learning activity where nurses contacted an adoption agency to learn more about the process for survivors with the goal of helping nurses provide patients with accurate information for making a well-informed decision regarding adoption.

Methods

Training program participants identified an adoption agency (local, state, or international) and conducted an interview using a semi-structured guide. Following the interview, participants created a summary of responses to the questions. We examined responses to each question using qualitative content analysis.

Results

Seventy-seven participants (98% completion rate) across 15 states provided a summary. Responses were distributed across these categories: adoption costs; steps required for survivors seeking adoption; challenges for survivors seeking adoption; birth parents’ reservations; and planned institutional changes to increase adoption awareness. The majority of respondents reported improving their knowledge of adoption and cancer, increased challenges for survivors, and the need to educate patients about the realities of adoption policies. The need for a letter stating the survivor was five years cancer-free was identified as a significant obstacle for survivors.

Conclusion

Nurses are charged with following practice guidelines that include recommendations for appropriate reproductive health referrals. Cancer survivors would benefit from a healthcare provider who can provide education and concrete information when patients are making a decision about fertility and adoption.

Keywords: Cancer, Survivor, Adoption, Oncology, Nurses

Introduction

A recent study documents 46% of male childhood cancer survivors (diagnosed before the age of 21) report being infertile;1 16% of female childhood cancer survivors report infertility,2 and this number climbs to 30% for those who received alkylating chemotherapy,3 which dominates many treatment plans. Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) cancer survivors include those patients who were initially diagnosed between the ages 15-39 according to the LIVESTRONG Foundation4 and the National Cancer Institute,5 and ages 15-29 according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.6 AYA cancer survivors may experience many unique challenges and quality of life (QoL) effects that persist beyond cancer diagnosis and treatment and well into survivorship, including issues with infertility.7 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) have guidelines suggesting that options to preserve fertility should be discussed with all patients prior to treatment.8 While both groups advocate discussion of standard fertility preservation methods such as embryo, oocyte and sperm cryopreservation and experimental options such as ovarian tissue freezing for females, testicular tissue freezing for males, the AAP policy also highlights the necessity to discuss adoption (pg. e1466).8 However, several barriers, challenges, and additional steps may exist for cancer survivors seeking to adopt a child; in order to discuss adoption as a family building option, healthcare providers should have a clear understanding of the adoption process and varying requirements across agencies, specifically in regards to adoptive parents with a cancer history. The primary goal of these discussions should be to provide the patient with timely, relevant, and accurate information so that the patient can make a well-informed decision regarding their reproductive health and future.

An early study of 132 cancer survivors found that 63% of female and 66% of male cancer survivors stated they would adopt if rendered infertile from their cancer treatment.9 While adoption may be a default option for clinicians when discussing the risks of infertility, available data from oncology healthcare suggests that healthcare providers and cancer organizations are not aware of the potential barriers, resources, and requirements for cancer survivors seeking to adopt a child.10 An oncology healthcare professionals study reported that 62% of respondents felt they knew ‘a little’ about adoption, while only 15% said they knew ‘a lot’ about adoption. This is concerning given members of the treatment oncology care team, particularly nurses, may have ongoing discussions about family building options with patients. They may be unprepared when the patient claims, ‘it's OK I'll just adopt.’ AYA cancer patients often espouse a ‘wait and see’ approach to fertility concerns, which may lead to unexpected challenges in future adoption efforts.11 The financial costs of adoption, ranging from $5,000 - $40,000 in domestic adoptions and $15,000 - $30,000 in international adoptions,12 may be a large obstacle for cancer survivors on top of costly treatment bills. Adoption is a viable family-building option for many cancer survivors after treatment related infertility; however, little is known about the rate at which cancer survivors successfully adopt a child or about their experiences negotiating a costly, and perhaps discriminatory, adoption process regarding the prospective parent's health history.

Oncology nurses have a vital role in patient care and, having regular interactions with the families, frequently engage in conversations that carry-over from the physician.13 Nurses assess and address a variety of clinical and psychosocial needs, and are the first point of contact for survivors during outpatient follow-up visits. AYA cancer patients are seen in these outpatient settings, many for decades following their cancer treatment, and oncology nurses often have long-term relationships lasting into middle age. Because of this, oncology nurses are also becoming more familiar with family-building issues among patients,14 which places nurses in an ideal position to incorporate adoption into their knowledge base.13

Oncology nurses have the opportunity to obtain specialized training in reproductive health and family-building for AYA patients through a dedicated program at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, FL. Educating Nurses about Reproductive Issues in Cancer Healthcare (ENRICH) is an 8-week eLearning training program that strives to inform oncology nurses of current needs, concerns, research efforts, options to reduce the risk of infertility, and tools necessary to guide the discussion on building a family in the future.15 Over five years, 250 oncology nurses will be trained and expected to disseminate their knowledge at their respective hospitals.

The training program includes both didactic and experiential learning activities to help nurses become more adept at communicating about reproductive health issues with cancer patients. The current study describes the results of an assigned learning activity where nurses contacted an adoption agency and conducted an interview to learn more about the adoption process for cancer survivors.

Methods

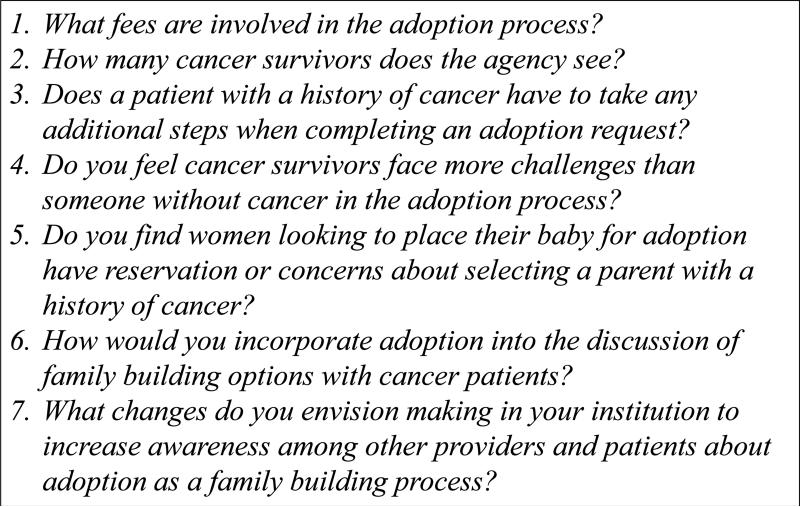

Participants who completed the program had R.N. training, saw five or more AYA patients a year, and worked in an oncology care setting. These participants were instructed to identify an adoption agency (local, state, or international) and conduct and interview with an administrator or intake counselor, using a semi-structured interview guide (Figure 1). The interview guide was developed with a panel of communication and reproductive health experts (advisory panel) to ensure they encompassed the learning objectives of the curriculum and the intent of the assignment. Following the interview, participants created a summary of responses to the questions. Results reported here were derived from a qualitative content analysis of these responses.

Figure 1.

Interview Guide for Adoption Agency.

Data Analysis

Using a deductive approach, two trained research assistants examined responses to each question and utilized an a priori code list to organize qualitative data (Table 1). As described by Miles and Huberman,16 coding procedures involved examining each individual response and assigning it a label (code) to represent the content of the response. Inter-rater reliability for this procedure was 95%; discrepancies were addressed and discussed by the reviewers in consultation with the lead author. Then, through a process of constant comparative analysis,17 coded responses were organized into thematic categories. As with the majority of Formatted: No underline, Font color: AutoFormatted: No underline, Font color: AutoFormatted: No underline, Font color: Auto qualitative research, the intent of this analysis was to obtain in-depth and diverse information, and not to quantify a preponderance of responses. 17 The goal was to showcase results covering a breadth of issues related to adoption processes and cancer survivors even when just one or two participants commented on a unique aspect of their experience.18

Table 1.

A Priori Code List

| Interview Question | Code Defined |

|---|---|

| ➢ What are the fees involved for adoption? | • Fee range • Financial assistance programs |

| ➢ How many cancer survivors does the agency see? | • Low number • Average • High number |

| ➢ Does a patient with a history of cancer have to take any additional steps when completing an adoption request? | • Letter from physician • Medical history • 5 years cancer-free • Life expectancy • Mental health status |

| ➢ Do you feel that cancer survivors would face more challenges than someone without cancer in the adoption process? | • High costs • Medical history disclosure • Wait times • International bans • No additional challenges |

| ➢ Do you find that women looking to place their baby for adoption have reservations or concerns about selecting a parent with a history of cancer? | • No impact • Positive impact • Negative impact |

| ➢ How would you incorporate adoption into the discussion of family building options with cancer patients? | • Mention briefly during fertility preservation (FP) options • Discuss in detailed during FP options • Only discuss if other FP options not possible |

| ➢ What changes do you envision making in your institution in order to increase awareness among other providers and patients about adoption as a family building option? | • Educate patients • Educate staff • Provision of resources |

Results

Seventy seven participants (98% assignment completion rate) across 15 states provided a summary; 100% were female, 91% were Non-Hispanic/Latino, and 85.7% were White. Detailed data on agency types were not available as results were dependent on learner choices for selecting the agency or representative. Responses were distributed across the following categories: adoption costs; steps required for cancer survivors seeking adoption; challenges for cancer survivors seeking adoption; birth parents’ reservations; and planned institutional changes to increase awareness about adoption.

Costs

Nurse participants reported a range of adoption fees from a low of $3,000 to a high cost of $75,000; the most commonly reported fees were between $20,000 and $30,000. Lower fees were typically associated with the adoption of special needs or older children. Participants learned adoptive parents could sometimes reduce fees by applying for grants or federal assistance. The majority of respondents were surprised at the high costs associated with adoption fees and most reported “I had no idea it was this expensive to adopt.”

Prevalence of Cancer Survivors Seeking Adoption

Participants learned that not all adoption agencies kept records on whether prospective adoptive parents were cancer survivors. Those who did track this reported an average of 10 former cancer patients a year seeking adoption.

“The agency said they don't have to report to anyone the health status of potential adoptive parents so they don't keep track of it.”

Additional Steps for Cancer Survivors Seeking Adoption

The majority of learners stated that though cancer survivors had few additional requirements, one such requirement was the need for a letter from a physician stating the health of each patents. The need for this letter could create significant complications depending on how the letter was interpreted by the agency. Most adoption agencies require a medical history from all prospective adoptive parents and a statement of health that may be shared with a birth mother. Having a cancer history could place restrictions on the adoption; in some cases agencies require survivors to be five years cancer free before an adoption could occur.

“The (medical history) could be difficult for an adoption agency to interpret.... No physician could ever guarantee a patient is cured, even after the 5 year remission gold-standard.”

“Letters from oncologists are required detailing the specifics of the cancer history and overall prognosis. Adoption agencies may contact the oncologist for further information.”

“(the agency) felt strongly that a cancer history as a child would not be an issue, however an adult recently treated for cancer would be an issue. Her agency manages it on a case by case basis and there is no stated policy.”

Some nurses reported that life expectancy was a strong factor in determining whether cancer survivors would be suitable as an adoptive parent.

“The prospective adoptive parent would need to show no signs of disease and have a normal life expectancy”

Some nurses reported agencies also mentioned the need for a mental health and support process for cancer survivors during the adoption process

“One additional step recommended for families with a cancer history is to take time for grief counseling. Infertility represents a loss and entering the adoption world will trigger feelings of grief all over again.”

Challenges for Cancer Survivors Seeking Adoption

Several participants reported learning during their interviews that the agencies indicated cancer survivors would not face any additional challenges, though the traditional process for every adoptive parent may be exacerbated for survivors. The majority reported that some of the requirements for adoption such as costs, wait times, medical history disclosure while not unique to cancer survivors, could pose significant barriers.

The majority of learners focused on the monetary costs of adoption as a potential barrier. Although adoption fees are potentially challenging for any person, regardless of cancer history, participants suggested high costs could be a unique barrier to a survivor, particularly if the costs of their cancer treatment were high.

“There are substantial fees associated with adoption. I forsee discussing adoption options with patients as they begin their cancer treatment could be discouraging to patients who are already concerned with the financial implications of their treatment.”

“Many cancer survivors already have a huge financial burden from their treatment costs. The fact that adoption requires a large upfront cost could deter families from pursuing this option.”

Another barrier participants felt would be unique to a cancer survivor attempting adoption was the medical history disclosure. The majority of participants learned a medical history and a letter from a physician is typically a requirement for everyone considering adoption and this information may or may not be shared with the birth mother. Participants noted learning adoption agencies encourage honesty and “open adoptions.” Based on medical disclosures a birth mother may potentially reject an adoptive parent based on a cancer history.

“Although the birth mother can request a closed adoption, adoptive parents cannot.... a birth mother will always be aware of the adoptive parents who have a history of cancer.”

“A specific challenge that occurs in open adoption is the release of medical background to birth parents. Sometimes this will impact the decision away from the cancer survivor.... This is disheartening to the cancer survivor.

Another challenge noted by a few participants was the waiting time required in the adoption process. Although the wait time is potentially stressful for all people pursuing adoption, survivors may find it exceptionally trying if they are anxious to begin a family and are facing uncertainty.

“This wait time can be very stressful for survivors, especially if they are still dealing with their illness.”

“The agency stressed being very honest with potential adoptive parents that their medical history may impact their wait time.... However, it is difficult to determine, as each birthmother is completely different.”

Yet another challenge noted by some participants related to learning that most international adoptions had greater restrictions for prospective adoptive parents with a cancer history. Participants reported that most countries did not have a complete ban on cancer survivors as adoptive parents but had stricter requirements about documentation of medical history and current health. They also noted some international adoption agencies did ban survivors from adopting newborns and would only allow them to adopt older children or those with special needs.

“Some countries excluded certain medical diagnoses and have a longer waiting time for cancer survivors or even certain body mass indexes that are judged too high.“

“Most international adoption agencies have a bias against cancer survivors adopting and do not even allow inquires by cancer survivors.”

Another encounter participants noted related to the concept of uncertainty and potentially creating a burden on the family if their cancer recurred or their health declined.

“The challenge for the cancer patients is that they are always looking over their shoulder for a recurrence.”

“Survivors may not feel comfortable with adoption. They understand the children have already experienced rejection or loss of their birth mother, so they would not want to risk dying and giving the child another loss.”

These nurses expressed relief that it may be easier for survivors to adopt than they originally anticipated.

“Overall, cancer survivors do not seem to face more challenges with adoption than other groups... the agency has worked on 500 successful adoptions over the last 20 years and she wasn't sure how many were cancer patients because cancer isn't really an important factor.”

“They have had people who have been done with treatment for a year or even people undergoing treatment.... They don't turn anyone away.”

Birth Parents’ Reservations

Participants were asked to investigate if the agency representative felt birth mothers tended to have reservations or concerns about selecting a parent with a history of cancer. The majority of respondents learned that typically a cancer history did not discourage a birth mother from choosing a survivor. These nurses reported learning the agencies’ main goal was to place a child in a loving stable home which was comprised of many factors, not just the prospective adoptive parent's medical history.

“She said from a birth mother's perspective a potential adoptee having had a cancer diagnosis is not something they usually ask about... nor do they ask medical questions in general.”

More than half of the adoption agencies reported that a cancer history may positively impact a birth mother's decision to select a survivor. Agencies reported birth mothers might feel confident in choosing a parent who has overcome hardships and has an appreciation for life.

“Occasionally a cancer survivorship was the connection that helped the birth mother select a particular adoptive couple possibly due to the empathy they may have had for a family member or someone in their social circle who had cancer...”

“Survivorship is often viewed as a positive quality in adoption... a personal battle with cancer can be endearing to the birth mother.”

However, a few agencies reported a cancer history in an adoptive parent could be discouraging for a birth mother and had encountered this situation occasionally.

“.... Biological mothers were uncomfortable placing with families with cancer in their history.”

“If the birth mother.... Has preconceived notions about cancer recurrence or survival this may affect if a survivor may get a child.”

However, the majority of participants learned that some birth mothers may actually look favorably on a cancer survivor and feel a stronger connection to the adoptive parents. [Considerations of this theme emerged again in response to question #5]

“I asked if birth mothers ever seem concerned about a potential mom or dad who has a history of cancer. They said they don't usually seemed fazed by it. She said many birth mothers have had someone in their family with cancer and they are not as concerned by that history.“

Incorporating the Adoption Discussion

Learners were asked how they would incorporate the subject of adoption with their patients in the future. About half of the participants said they would discuss adoption at the same time as discussing other fertility preservation options.

“All future parenting options should be considered and discussed at the same time... adoption, sperm banking, oocyte, embryo storage”

About one third of the participants thought adoption should be mentioned only briefly during the pre-treatment discussions of fertility preservation. These participants felt the emphasis should be on oocyte, embryo or sperm cryopreservation and adoption should be discussed in greater detail post-treatment or when the patient was ready to actually begin family building.

“I see the utility of adoption discussion at two time points. While the sexual health discussion will be continually revisited, adoption could be mentioned in the pre-treatment fertility discussion as one option and then discussed in greater detail with more specifics during our post-treatment survivorship interview. “

A minority of nurses felt adoption should only be discussed if other fertility preservation options were not successful or not desired.

“There are a certain sub-set of patients who are expected to become infertile based on their treatment and for whom fertility preservation is not an option, is not practical or is not desired – they would benefit from discussion about adoption as an option.”

Institutional Changes to Increase Awareness about Adoption

Participants were asked what changes they would make in their institution to increase awareness among other providers and patients about adoption as a family building option based on the information they obtained during their interview with an adoption agency. The majority of nurses focused on improving education and resources for patients. They also reported feeling more confident and knowledgeable about the adoption process and felt an improved ability to discuss adoption with patients. Some participants stated they would now encourage patients to consider adoption.

“Now instead of avoiding this topic and deferring to the physician, I can start the discussion and share my information and resources.”

“The most important thing I learned from this interview was to encourage the survivor to do their homework before approaching an agency. Call and ask specific health related questions up front so there are no surprises as the process continues.”

“Information discussed with patients should always be given in writing.... I would like to see a general handout... for patients following the fertility discussion.”

Other participants felt the first step in increasing patient education was to improve awareness and knowledge about adoption to all staff. This included making presentations, arranging meetings and overall sharing of knowledge with other nurses and physicians.

“I plan to increase awareness to other health care providers by presenting in- services to staff and making information available to patients and health care team members in the clinic.”

“I will send out an email to clinic doctors and nurses sharing the extra barriers survivors may face during the adoption process. It is important they know in case future patients inquire about family building options.”

Discussion

Emergent literature emphasizes the importance of fertility preservation for cancer survivors of reproductive age. Most often emphasizing need for introducing fertility preservation options to patients prior to the initiation of treatment and the need to educate and train clinicians about fertility preservation,19, 20 the literature has yet to provide insight into what happens to these young adults when, in fact, they engage reproductive specialists and initiate technologically-assisted means of reproduction. For many, these procedures are not successful, and survivors examine their remaining options, including adoption or the decision to not have children. ENRICH was an opportunity to derive insight into the issues and challenges cancer survivors may face when pursing parenthood through adoption.

The finding about agencies restricting adoption to cancer survivors or requiring them to provide a note from their doctor exposes a discriminatory practice akin to restricting employment opportunities for people with disabilities prior to the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Requiring health histories of adopting parents, cancer survivors or not, may be a violation of the intent if not the spirit of the ADA – to protect privacy and civil rights. Furthermore, there is no evidence to suggest that a cancer survivor or parent with any kind of disability is any less able than persons without a disabling health condition or cancer history to raise children in a loving, caring, and protective manner. Indeed, nurse participants identified as agencies’ main goal the placement of children in loving and stable homes regardless of adoptive parent's medical history. The comments reflecting agencies’ and nurses’ uncertainty about survivors’ parenting abilities suggest that survivors are naïve to their own mortality and risks for long-term or late effects, and that they have not considered these risks before initiating the adoption process. While cancer survivors’ risks for mortality, morbidity, or debilitating conditions may be greater than those of non-survivors, there are no guarantees that adopting parents without a debilitating health history who engage in adoption will not at some point confront disease or health problems that could affect their parenting. Using cancer history as a factor for determining readiness for adoption is discriminatory, just as it is in the employment arena. Advocacy and education efforts are needed to preclude adoption agencies from using cancer history as a reason to deny adoption.

Adoptive parents have supported a nursing curriculum that integrates issues of adoption in order to better prepare nurses to interact with adopting families.21 This education would also allow nurses to be better equipped in providing insight for cancer patients who presume adoption is a failsafe method to having a family, or for survivors who seek adoption and are uninformed about the process. Nurses serve as educators, advocates, reporters, and information gatherers who continually evolve with the needs of their patients.22 Understanding the challenges and facilitators of adoption for cancer survivors will allow oncology nurses to be confident when discussions arise.

Conclusion

Nurses are charged with following practice guidelines that include recommendations for appropriate reproductive health referrals. With the issue of health and remission being a significant factor in the adoption process, cancer survivors would benefit from a healthcare provider who can educate patients about adoption policies and provide concrete information for patients when they are making decisions about fertility and adoption. The referral process is most successful when nurses have best practice guidelines to inform policy and decrease role confusion.23

Table 2.

Learner Demographics

| Total (N=77) % | |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 4 (5.2%) |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 71 (92.2%) |

| Participant chose not to respond | 2 (2.6%) |

| Race | |

| White | 65 (84.4%) |

| Black/African-American | 1 (1.3%) |

| Asian | 1 (1.3%) |

| More than one race | 6 (7.8%) |

| Participant chose not to respond | 4 (5.2%) |

| Other | 3 (3.6%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 0 (0.0%) |

| Female | 76 (98.7%) |

| Participant chose not to respond | 1 (1.3%) |

| Highest Degree | |

| Associate's | 8 (10.4%) |

| Bachelor's | 22 (28.6%) |

| Graduate | 47 (61.0%) |

| Workplace Setting | |

| Academic Cancer Center | 34 (44.2%) |

| Community Cancer Center | 11 (14.3%) |

| University Hospital | 11 (14.3%) |

| Community Hospital | 8 (10.4%) |

| Private Practice | 3 (3.9%) |

| Other | 10 (12.9%) |

| Years in Nursing | |

| 1-10 | 26 (33.8%) |

| 11-20 | 20 (26.0%) |

| 21-30 | 8 (10.4%) |

| 31-40 | 22 (28.6%) |

| Participant chose not to respond | 1 (1.2%) |

Acknowledgments

Funding: ENRICH (formerly the Fertility Reproduction and Cancer Training Institute for Oncology Nursing) is funded by a National Cancer Institute R25 Training Grant: #5R25CA142519-02.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Wasilewski-Masker K, Seidel KD, Leisenring W, et al. Male infertility in long-term survivors of pediatric cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2014;8:437–447. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0354-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barton SE, Najita JS, Ginsburg ES, et al. Infertility, infertility treatment, and achievement of pregnancy in female survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:973–981. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70251-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sklar CA, Mertens AC, Mitby P, et al. Premature menopause in survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:890. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The LIVESTRONG Foundation The Livestrong Young Adult Alliance. 2012 Retreived from: http://www.livestrong.org/what-we-do/our-actions/programs-partnerships/livestrong-young-adult-alliance/

- 5.National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. 2014 Retrieved from: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/aya.

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. 2014 Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/survivorship/what_cdc_is_doing/research/adolescent_young.htm.

- 7.Zebrack BJ, Casillas J, Nohr L, Adams H, Zeltzer LK. Fertility issues for young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13:689–699. doi: 10.1002/pon.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Academy of Pediatrics From the American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Statement AAP Publications Retired and Reaffirmed. Policy Statement: Alternative Routes of Drug Administration—Advantages and Disadvantages. Pediatrics. 100:143–152. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schover LR, Rybicki LA, Martin BA, Bringelsen KA. Having children after cancer. Cander. 1999;86:697–709. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990815)86:4<697::aid-cncr20>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen A. Third-party reproduction and adoption in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;34:91–93. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nieman CL, Kinahan KE, Yount SE, et al. Fertility Preservation and Adolescent Cancer Patients: Lessons from Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer and Their Parents. Cancer Treat Res. 2007;138:201–217. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72293-1_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Child Welfare Information Gateway The Costs of Adopting. 2011 Feb; Retrieved from: https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/s_costs.pdf.

- 13.Hershberger PE, Finnegan L, Pierce PF, Scoccia B. The decision-making process of young adult women with cancer who considered fertility cryopreservation. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2013;42:59–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clayton H, Quinn GP, Lee JH, et al. Trends in clinical practice and nurses’ attitudes about fertility preservation for pediatric patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:249–255. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.249-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vadaparampil ST, Hutchins NM, Quinn GP. Reproductive health in the adolescent and young adult cancer patient: an innovative training program for oncology nurses. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28:197–208. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0435-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. 2nd edition Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage; London: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldfarbemail S, Mulhall J, Nelson C, Kelvin J, Dickler M, Carter J. Sexual and Reproductive Health in Cancer Survivors. Seminars in Oncology. 2013;40:726–744. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vindrola-Padros C, Mitu K, Dyer K. Fertility Preservation Technologies for Oncology Patients in the US: A Review of the Factors Involved in Patient Decision Makin. Technology and Innovation. 2012;13:305–319. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foli KJ, Schweitzer R, Wells C. The personal and professional: nurses' lived experiences of adoption. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2013;38:79–86. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0b013e3182763446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hewitt ME, Bamundo A, Day R. Perspectives on post-treatment cancer care: qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2270–2273. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edwards N, Davies B, Ploeg J, Virani T, Skelly J. Implementing nursing best practice guidelines: Impact on patient referrals. BMC nursing. 2007;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]