Abstract

Background

Streptococcus pneumoniae Neuraminidase A (NanA) is a multi-domain protein anchored to the bacterial surface. Upstream of the catalytic domain of NanA is a domain that conforms to the sialic acid-recognising CBM40 family of the CAZY (carbohydrate-active enzymes) database. This domain has been identified to play a critical role in allowing the bacterium to promote adhesion and invasion of human brain microvascular endothelial cells, and hence may play a key role in promoting bacterial meningitis. In addition, the CBM40 domain has also been reported to activate host chemokines and neutrophil recruitment during infection.

Results

Crystal structures of both apo- and holo- forms of the NanA CBM40 domain (residues 121 to 305), have been determined to 1.8 Å resolution. The domain shares the fold of other CBM40 domains that are associated with sialidases. When in complex with α2,3- or α2,6-sialyllactose, the domain is shown to interact only with the terminal sialic acid. Significantly, a deep acidic pocket adjacent to the sialic acid-binding site is identified, which is occupied by a lysine from a symmetry-related molecule in the crystal. This pocket is adjacent to a region that is predicted to be involved in protein-protein interactions.

Conclusions

The structural data provide the details of linkage-independent sialyllactose binding by NanA CBM40 and reveal striking surface features that may hold the key to recognition of binding partners on the host cell surface. The structure also suggests that small molecules or sialic acid analogues could be developed to fill the acidic pocket and hence provide a new therapeutic avenue against meningitis caused by S. pneumoniae.

Background

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a human pathogen responsible for respiratory tract infections, septicaemia and meningitis. Several virulence factors contribute to colonization and early infection processes [1]. Sialidases from pathogenic bacteria are considered as key virulence factors, as they remove sialic acid from host cell surface glycans, unmasking certain receptors to facilitate bacterial adherence and colonization. All S. pneumoniae clinical isolates investigated to date possess prominent sialidase activities. Three sialidases, NanA, NanB and NanC, are encoded by S. pneumoniae genomes. A study of sialidase genes in clinical pneumococcal isolates identified nanA, nanB and nanC to be present in 100 %, 96 % and 51 % of these strains, respectively [2]. Pneumococcal strains with knockouts of nanA or nanB, and studied in mouse models, show that both proteins are essential to S. pneumoniae infection of the respiratory tract and sepsis [3]. NanA, specifically, has been shown to play an important role in host-pneumococcal interactions in the upper respiratory tract [4, 5], and is involved in biofilm formation [6]. It has also been shown to desialylate competing bacteria such as Neisseria meningitidis and Haemophilus influenzae, potentially giving S. pneumoniae an advantage in shared bacterial niches [7]. Furthermore, the NanA from S. pneumoniae has also been shown to promote inflammation by disrupting sialic acid based recognition of CD24 by SiglecG in mice (the equivalent of SIGLEC10 in humans) [8].

From amino acid sequence comparison of bacterial sialidases, NanA is modular by nature and its domain organisation is similar to other known bacterial sialidases (Fig. 1). The enzyme contains a catalytic domain flanked by an N-terminal carbohydrate-binding domain (CBM) that is downstream of a signal sequence, followed by a region of predicted disorder. At the C-terminus, there is a region rich in proline, glycine, threonine and serine containing a sequence of 20 amino acids repeated three times contiguously followed by an LPXTG anchor sequence. Subsequent analysis of multiple pneumococcal strains showed that the nanA gene is highly diverse, mainly in truncations in the C-terminal region, but that the N-terminal CBM and catalytic domain are conserved [9]. Two studies have reported the importance of NanA in allowing S. pneumoniae to adhere to and invade the blood–brain-barrier (BBB), through the use of human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hBMECs). In particular the N-terminal CBM domain (described in the study as a laminin G-like domain) was found to be the critical determinant of this event [10, 11]. Both of these studies showed that the catalytic activity of NanA only played a minor role in the adhesion/invasion event, with one study showing that the N-terminal CBM was also involved in the induction of neutrophil chemo-attractants IL-8, CXCL-1 and CXCL-2 [11].

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the NanA domains

We recently cloned the N-terminal CBM domain of NanA (residues 121–305) and carried out a glycan array screen that showed the domain binds to sialic acid [12], and as such is a Family 40 CBM as defined in the CAZY database [13]. We have also engineered multivalent forms of this domain, designed to adhere with high affinity to sialic acid receptors in the respiratory tract, and have shown that they prevent infection from influenza viruses in a mouse model. Preliminary analysis of immunomodulators during this influenza study supports the ability of this domain to stimulate the immune system in mice, specifically IL-1β, MIP-2 (the mouse homolog of IL-8), IFN-γ and TNF-α [12].

To date, only the catalytic domain of NanA has been studied structurally, and is the subject of small molecule inhibitor studies [14–16]. Here we describe the crystal structure of the S. pneumoniae NanA CBM40 domain, hereafter named SpCBM. Crystal structures of SpCBM, complexed with α2,3-sialyllactose (Neu5Ac-α2,3-Gal-β1,4-Glc, from here on referred to as 3’SL) and α2,6-sialyllactose (Neu5Ac-α2,6-Gal-β1,4-Glc, from here on referred to as 6’SL) are also described. The structure of SpCBM is compared to other known CBM40 structures showing that it shares a similar fold. In contrast to the other CBM40 domains, SpCBM has a deep water-filled pocket adjacent to the N-acetyl moiety of sialic acid and surrounded by a positively charged surface. In the crystal structures, the acidic pocket is partially occupied by a lysine residue from a symmetry-related molecule. The structure of SpCBM suggests that it may recognise a second receptor that may be responsible for the induction of chemokines, and the BBB invasion event.

Results

Structure overview

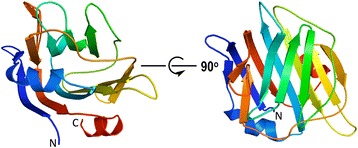

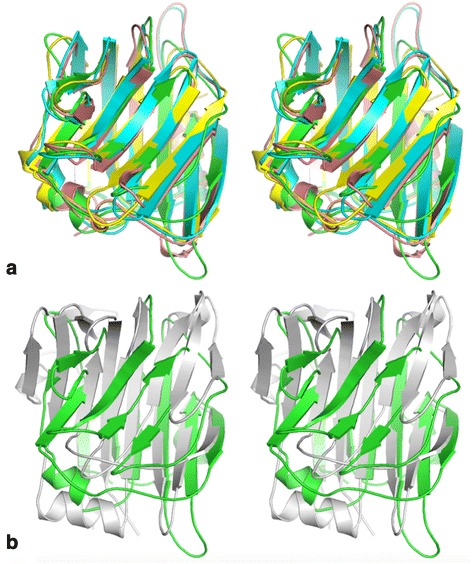

All residues (from Val121 to Ser305) of the expressed CBM were clearly identifiable in the SpCBM crystal structure. As shown in Fig. 2, the native structure constitutes a central β-sandwich (comprising one antiparallel β-sheet containing five-strands and a second antiparallel β-sheet containing six-strands), a β-hairpin on one side of the sandwich, an α-helix present between the β-sheets and a C-terminal α-helix packing against the β-sandwich. When compared to other CBM40 structures, SpCBM is structurally homologous to CBM40 modules from C. perfringens NanJ [PDB ID: 2 V73]; RMSD 1.7 Å for 169 Cα’s [17], S. pneumoniae NanB [PDB ID: 2VW0]; RMSD 2.0 Å for 170 Cα’s [18], M. decora NanL [PDB ID: 2SLI]; RMSD 2.0 Å for 176 Cα’s [19], and V. cholerae NanH [PDB ID: 1W0P]; RMSD 3.1 Å for 134 Cα’s [20]. The superposition of SpCBM with these structurally homologous domains is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

Overall structure of the SpCBM. Cartoon representation of the SpCBM in two orientations, coloured in rainbow colours from blue at the N-terminus to red at the C-terminus

Fig. 3.

Stereo view of the cartoon representation of the superimposition of SpCBM with other CBM40 family members. a SpCBM is shown in green, NanB-CBM is shown in blue, NanJ-CBM is shown in yellow and NanL-CBM is shown in pink. b Superimposition of SpCBM with NanH-CBM. NanH-CBM is shown in grey

Ligand binding site

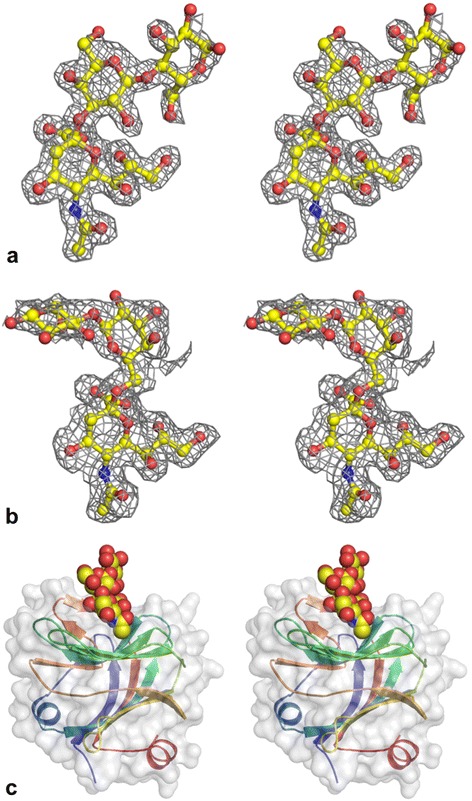

For the complexed structures, both 3’SL and 6’SL were co-crystallized with SpCBM. There are no significant conformational changes between the apo SpCBM structure and the complexed structure, and superimposition of the apo and holo structures gives an RMSD of 0.48 Å over all Cα atoms for both 3’SL and 6’SL. Difference electron-density maps of both 3’SL and 6’SL molecules, in complex with SpCBM, are clearly defined (Fig. 4), particularly the sialic acid moiety of each sialoside. In the 3’SL and 6’SL complexes, the protein structures are highly similar, giving an RMSD of 0.06 Å for all of the Cα atoms while the sialic acid moieties of the ligands are completely superimposable. The lactose moieties of the 3’SL and 6’SL, however, point in opposite directions (Fig. 4a & b). In 3’SL, lactose does not interact with the protein, although O6 of the glucose moiety interacts with O9 of sialic acid. In 6’SL, glucose O6 interacts with the side chain of Asp180. For both ligands, the lactose B-factors are significantly higher than the corresponding sialic acid moiety.

Fig. 4.

3’SL and 6’SL co-complexed with SpCBM. a Stereo view of Fo-Fc map of 3’SL co-complex contoured at 2.5σ level. b Stereo view of Fo-Fc map of 6’SL co-complex contoured at 2.5σ level. c Stereo view of 3’SL (shown in spheres) bound to the SpCBM substrate-binding site

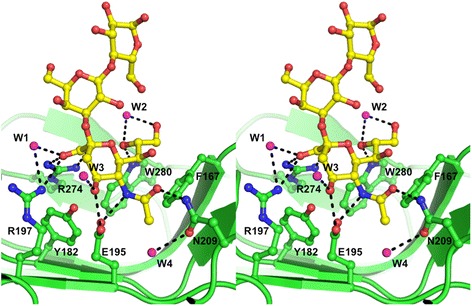

For SpCBM, the residues that are involved in the interaction are mainly donated from the concave surface formed by the β-hairpin and three β-strands (Fig. 4c). As shown in Fig. 5, the carboxylate group of Neu5Ac forms a bidentate interaction with Arg274, a common feature in proteins that bind sialic acid. Arg197 also interacts with one of the carboxylate oxygens of Neu5Ac. Other Neu5Ac atoms make additional interactions with SpCBM: O4 interacts with the side chain of Glu195 as does the N5 of the acetamido group; the O10 carbonyl oxygen of the acetamido group interacts with Asn209; the glycerol O8 hydroxyl oxygen interacts with the imidazole nitrogen of Trp280. Phe167 provides a hydrophobic platform supporting the glycerol carbons (C7 to C9) that are ~4 Å away, and also forms part of the hydrophobic pocket accommodating the acetamido methyl group. A number of water molecules are seen to bridge interactions between Neu5Ac and the protein. Details of the major interactions between SpCBM and ligand are listed in Table 1.

Fig. 5.

Stereo view of Neu5Ac binding sites of SpCBM. 3’SL is shown in yellow carbon atoms and waters are shown in magenta. SpCBM residues that are involved in the interaction are shown in stick representation with green carbon atoms. Hydrogen bonds are shown as black dotted lines

Table 1.

Interactions between SpCBM and 3’SL. Intermolecular hydrogen bonds between SpCBM and 3’SL are listed. Water molecules bound to 3’SL are also detailed

| 3’SL | Protein/Water atoms | Distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| O-1 A | Arg274-N-η2 | 2.88 |

| O-1 A | Arg197-N-η1 | 3.15 |

| O-1 A | H2O (W1) | 2.74 |

| O-1 B | Arg274-N-η1 | 2.90 |

| O-4 | Glu195-O-ε1 | 2.71 |

| O-4 | Glu195-O-ε2 | 3.39 |

| O-4 | H2O (W3) | 2.66 |

| O-8 | Trp280-N-ε1 | 2.87 |

| O-8 | H2O (W2) | 3.15 |

| O-9 | H2O (W2) | 2.87 |

| O-10 | Asn209-N-δ2 | 2.79 |

| N-5 | Glu195-O-ε1 | 3.39 |

| N-5 | Glu195-O-ε2 | 2.77 |

Acidic cavity adjacent to sialic acid binding site

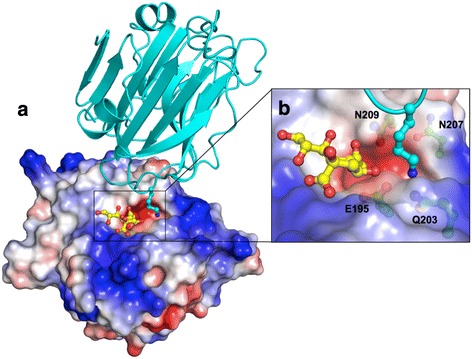

A striking feature of the protein is a deep, negatively charged cavity adjacent to the sialic acid binding site (Fig. 6a). This pocket is formed by four residues (Glu195, Gln203, Asn207 and Asn209), and is occupied by a lysine from a symmetry-related molecule (Fig. 6b). Interestingly, a region immediately adjacent to this pocket and to the sialic acid binding site is highlighted by the results of the meta-PPISP server as a likely protein interaction site (Fig. 7). No other protein binding sites on SpCBM are predicted, and no such sites are predicted on the CBMs of NanB, NanL or NanH. NanJ CBM has a low-scoring patch in a region that overlaps with the corresponding patch on SpCBM.

Fig. 6.

Potential functional cavity of SpCBM. a The surface electrostatic view from the top of the binding site of SpCBM and a cavity adjacent to the active site, which is occupied by a lysine from a symmetry related molecule (shown in cyan). b Close-up view of the interaction between the lysine and the protein. The solvent-accessible surface of SpCBM is coloured based on the electrostatic potential from −7 (red) to +7 (blue) kT/e, calculated using the APBS tool in PyMOL [34, 35]

Fig. 7.

Prediction of protein-protein interaction site. The SpCBM surface is coloured according to meta-PPISP score. Residues are coloured from green (low propensity for protein binding) to red (high propensity). The sialic acid moiety of 3’SL is shown in stick representation with purple carbon atoms

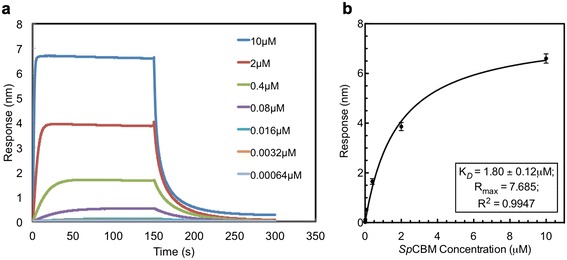

Kinetics and binding affinity of SpCBM interaction with 3’SL

A sensogram showing the association and dissociation of SpCBM binding to 3’SL is shown in Fig. 8a. The kinetic parameters for the interaction based on global fitting of raw data using a 1:1 (Langmuir) binding model gave a KD value of 1.8 ± 0.13 μM and R2 of 0.99 (data not shown). As equilibrium was also observed with the different SpCBM concentrations, a KD value of 1.8 ± 0.12 μM was determined from steady state binding by plotting the response at equilibrium against SpCBM concentration (Fig. 8b).

Fig. 8.

Bio-layer Interferometry. Association of SpCBM with 3’SL immobilized to a probe via a biotin linkage as measured using bio-layer interferometry. a Sensogram showing the response units against increasing concentrations of SpCBM. b Steady-state binding of SpCBM-3’SL interaction determined by plotting the response at equilibrium against SpCBM concentration and globally fitted using a 1:1 (Langmuir) binding model

Discussion

CBM40 domains have been described structurally for other sialidases from Vibrio cholerae NanH [20], Clostridium perfringens NanJ [17], S. pneumoniae NanB [18] and Macrobdella decora NanL [19], with sialic acid binding only visualised in the first two. The CBM40 domains all share a common lectin β-sandwich fold with two antiparallel β-sheets containing five and six strands, in addition to other secondary structural elements. The sialic acid binding site is located in the concave surface of the five-stranded sheet, although the nature of the ligand interactions in the sialic acid complexes with V. cholerae NanH and C. perfringens NanJ are quite different and the binding sites are at different locations on the concave surface.

In their description of C. perfringens NanJ, Boraston et al. pointed out that there appear to be two subfamilies within the CBM40 family, one typified by C. perfringens NanJ and the other by V. cholerae NanH [17]. The structure of SpCBM confirms that it belongs to the subfamily that includes C. perfringens NanJ and also S. pneumoniae NanB and M. decora NanL CBMs.

Previous reports mentioned that certain sialic acid binding residues from C. perfringens NanJ CBM (namely Glu79 and Arg81) were conserved in closely related CBMs from S. pneumoniae NanB and M. decora NanL but differed in NanA CBM. However, an alignment based on the SpCBM structure reveals that these residues are, in fact, conserved and correspond to NanA residues Glu195 and Arg197. Other residues in the immediate area (Arg274 and Tyr182) are also conserved and form very similar interactions as Arg151 and Tyr66 in NanJ. In S. pneumoniae NanB, residues corresponding to NanA Glu195, Arg197, Arg274 and Tyr182 are conserved and adopt very similar positions to that of NanA, suggesting that NanB is likely to bind sialic acid in a similar manner.

The binding mode in the region of the glycerol moiety is somewhat different in NanJ CBM and SpCBM. In SpCBM, a hydrogen bond is formed between Trp280 and the C-7 hydroxyl, whereas the corresponding residue in NanJ (Tyr158) cannot make this interaction, instead forming a different H-bond to the glycerol group via Asn156. The space filled by this Asn side chain, along with the adjacent residue Tyr155, is not occupied by any residues in the corresponding area of SpCBM or NanB, creating a more open binding pocket in the streptococcal proteins.

From binding affinity analysis, the dissociation constant, KD for SpCBM-3’SL interaction was found to be in the affinity range similar to that measured for the isolated CBM40 from V. cholerae NanH interacting with 3’SL (1.8 μM) as determined by Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [21]. This suggests that the sialic acid binding pocket of both CBM40s may be similar. On examination of the residues involved in sialic acid binding by VcCBM [20], both CBM40s involve a comparable number of direct and water-mediated interactions that target the sialic acid moiety alone, despite the overall topology of the binding sites being different between them.

Besides the classic function of binding to sialic acid, NanA was reported to enhance the S. pneumoniae interaction with human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hBMECs) via an adhesin function of NanA-CBM, which can potentially facilitate the entry of bacterial pathogens into the central nervous system (CNS), even with little contribution of the sialidase activity [10]. However, it is still not completely clear which receptor in the hBMECs is important for this process, and how it could be recognized by NanA-CBM. In the current study, the surface electrostatic view shows that there is a deep, negatively charged cavity with positively charged surface next to the sialic binding site (Fig. 6a), which is not present in the other family 40 CBMs. Of the four amino acids that form the cavity, only Glu195 is conserved, whereas Gln203, Asn207 and Asn209 are present in a region of sequence that exhibits low homology in family 40 CBMs, suggesting that this surface feature is exclusive to S. pneumoniae NanA. The four residues interact with a lysine from a symmetry related molecule (Fig. 6b). Therefore, it is possible that this region is important for S. pneumoniae NanA CBM interaction with a host cell receptor. This proposed interaction site for a binding partner for NanA CBM is supported by the output of the metaPPISP web server, which combines results from three different methods for predicting protein-protein interaction sites. The predicted region lies directly adjacent to the sialic acid binding site and the acidic pocket.

Conclusions

In summary, we have determined the structure of the isolated form of CBM from S. pneumoniae NanA, which has been identified as a Family 40 CBM due to its ability to bind the terminal sialic acid of glycoconjugates. Our findings suggest that this domain may enhance the virulence of NanA by targeting and binding to a variety of linkage-independent sialic acid receptors that line the surface of respiratory epithelial cells. Further experiments to determine the NanA binding partner(s) are ongoing. The SpCBM domain, in addition to showing promise as a bio-therapeutic against respiratory pathogens [12, 22], is a potential drug target and may be exploited as part of a combinatorial drug design approach to inhibit NanA attachment and catalysis.

Methods

Cloning, expression, and purification

The gene encoding the SpCBM domain from S. pneumoniae NanA (UniProt: P62575) was generated by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the following primers 5’-GGCTCCATGGTGATAGAAAAAGAAGATG-3’ and 5’-GCACTCGAGTCATTTAAAAAGTTGACTACG-3’ (NcoI and XhoI restriction sites in bold) and pQE30 vector containing the nanA sialidase gene as template. The PCR fragment was purified using a Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN) prior to ligation into an appropriately digested pEHISGFPTEV vector [23]. The construct was propagated in Escherichia coli DH5α cells with positive colonies identified by colony PCR. The DNA sequence was confirmed by sequencing (The Sequencing Service, University of Dundee, UK), prior to transforming E. coli BL21 (DE3) expression strain (Novagen) for protein production.

Expression of SpCBM was achieved by inoculating Luria Broth (LB) medium containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin with a single colony and incubating at 37 °C until cultures reached an absorbance at 600 nm (A600) of 0.6. Cultures were subjected to heat shock at 42 °C for 20 minutes prior to cooling to 25 °C and induced with isopropyl thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.5 mM final concentration) to induce expression of SpCBM. Cultures were left to incubate further overnight at 18 °C before harvesting by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 20 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 20 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM sodium chloride, pH7.4) containing 10 mM imidazole and 300 mM sodium chloride with DNase I (Sigma, final concentration 20 μg/ml) and EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablets (one tablet per 50 ml extract, Roche Diagnostics). The cell suspension was lysed by sonication to disrupt cells then subjected to centrifugation at 40,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris. Clarified supernatants were collected and filtered with a 0.2 μm pore size syringe-driven filter before further protein purification.

The soluble cell extract was initially loaded onto a 20 ml HisPrep FF 16/10 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in PBS containing 10 mM imidazole and 300 mM sodium chloride. The column was then washed with PBS buffer containing 20 mM imidazole and 300 mM NaCl before eluting bound protein using the PBS/NaCl buffer supplemented with 250 mM imidazole. Eluted fractions were then treated with TEV protease overnight to remove the His-GFP tag. Cleaved proteins were further purified by re-applying to the 20 ml HisPrep FF 16/10 column. The collected flow through was concentrated before performing size exclusion chromatography using a HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S-200 HR column (GE Healthcare), which was pre-equilibrated in 20 mM sodium citrate, pH6.0 containing 50 mM sodium chloride. Fractions from the observed peaks were analyzed separately by SDS-PAGE gel. Protein identity and integrity were confirmed by mass spectrometry (BSRC Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Facility, University of St Andrews). Purified SpCBM was collected, concentrated and stored at −80 °C for future use.

Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI)

The binding affinity assay of SpCBM to 3’SL was performed using the ForteBio Octet RED384 system (ForteBio). Assays were performed in black 96 wells plates (Nunc™ F96 MicroWell™ plate, Thermo Scientific) using PBS containing 0.002 % Tween-20 as running buffer at 25 °C. Super streptavidin-coated (SSA) biosensor tips (ForteBio) were pre-hydrated in 200 μl running buffer for 10 min followed by equilibration in PBS for 60 s. Tips were non-covalently loaded with a 25 μg/ml solution of a multivalent biotinylated 3’SL-polyacrylamide (Glycotech) in running buffer for 300 s followed by a wash of 60 s in the same buffer. All sensors, including reference sensors (no ligand), were blocked with biocytin (Life Technologies) for 60 s, to prevent non-specific interactions of protein to the sensor surface, followed by a further wash for 60 s. Association of biotinylated ligand with SpCBM (5-fold dilution series using a 10 μM stock in running buffer) was performed for 150 s before dissociation of binding was performed using running buffer for 150 s. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data were processed to calculate kinetic and affinity parameters using the ForteBio software.

Protein crystallization

Purified SpCBM was concentrated to 33 mg/ml based on the results of precrystallization assay kit screening (Hampton Research). All the subsequent crystallization experiments were done at 20 °C by the sitting-drop, vapour-diffusion method. Initially, commercial kits Crystal Screen, SaltRx, Index (Hampton Research), Wizard, Cryo I&II (Emerald BioSystems), JCSG Suite, PACT Suite and PEGs Suite (Qiagen) were screened by a Honeybee 963 robot system (Genomic Solutions) for protein crystallization. Conditions with crystalline materials were selected for crystallization optimization. After several rounds of optimizations, the best crystals were obtained in 120 mM MMT (molar ratios 1:2:2 of DL-malic acid: MES: Tris Base) buffer pH9.0, 25 % (w/v) PEG1500. Crystals appeared the next day and reached their maximum size within two weeks. Structures of complexes with Neu5Ac derivatives were obtained by co-crystallization with SpCBM. Protein solution (33 mg/ml) containing 5 mM ligand was incubated at 4 °C for 30 min followed by mixing with an equal volume of reservoir solution (100 mM MMT pH9.0 and 28 % (w/v) PEG1500). The crystals appeared the next day and reached maximum size in 3–4 days.

X-ray diffraction data collection and processing

Crystals were cryoprotected by transfer for a few seconds to a solution of the crystallization buffer with 5 % (w/v) ethylene glycol added before data collection at 100 K. All X-ray diffraction data were collected in-house on a Rigaku 007HFM (Cu anode, λ = 1.54178) X-ray generator, with a Saturn 944CCD detector. HKL2000 was used for data processing and integration [24]. Apo SpCBM crystals belong to the monoclinic space group P21, with two monomers in an asymmetric unit. Crystals of complexes were also P21 but contained one monomer per asymmetric unit. Data collection statistics are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Crystal | Apo | 3’SL complex | 6’SL complex |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collectiona | |||

| Space group and cell dimensions (Å,°) | P21 | P21 | P21 |

| a = 39.2, b = 67.0, c = 66.8, β = 92.3 | a = 42.6, b = 44.5, c = 43.0, β = 97.0 | a = 42.5, b = 44.6, c = 43.0, β = 97.0 | |

| Resolution (Å) | 67.0-1.8 | 44.5-1.8 | 44.6-1.8 |

| Unique reflections | 29,236 | 12,926 | 13,634 |

| Completeness (%) | 97 (74) | 92 (76) | 97 (83) |

| Redundancy | 2.5 (2.0) | 2.4 (1.7) | 3.0 (2.2) |

| R-mergeb | 0.031 (0.069) | 0.069 (0.108) | 0.049 (0.093) |

| I/σI | 43.9 (22.7) | 38.7 (16.8) | 44.1 (16.8) |

| Refinement | |||

| Reflections used | 27,743 | 12,277 | 12,950 |

| Number of protein atoms | 2,986 | 1,532 | 1,528 |

| Number of ligand atoms | - | 43 | 43 |

| Number of waters | 403 | 166 | 148 |

| R-factorc | 0.163 | 0.143 | 0.150 |

| R-freed | 0.218 | 0.198 | 0.195 |

| rmsd bond lengths (Å) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| rmsd bond angles (°) | 2.10 | 2.04 | 2.08 |

| Average B-factors (Å2) | |||

| all atoms | 16.3 | 15.2 | 15.9 |

| ligand atoms | - | 27.8 | 32.4 |

| waters | 28.5 | 27.8 | 26.4 |

| Molprobity score | 1.80 | 1.20 | 1.40 |

| Ramachandran favoured/outliers (%) | 97/0 | 98/0 | 97/0 |

aNumbers in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell

bR-merge = Σhkl Σi | Ihkl, i - < Ihkl > | / Σhkl < Ihkl>

cR-factor = (Σ | |Fo| - |Fc| |) / (Σ |Fo|)

dTest set comprised 5 % of reflections

Structure determination and refinement

The leech trans-sialidase structure [PDB ID: 2SLI] was used to solve the SpCBM structure by molecular replacement with the PHASER program from the CCP4 suite [25, 26]. Refinement was carried out with the program REFMAC5 [27] from the CCP4 suite and the refined model was manually adjusted in Coot [28]. After further refinement with REFMAC5, the structures were inspected and validated with Coot and MolProbity [29]. Refinement statistics are summarized in Table 2.

Prediction of protein-protein interaction sites

The meta-PPISP server was used to predict potential protein-protein interaction sites on SpCBM [30]. The server combines three different methods in a linear regression analysis, a strategy which improves accuracy compared to the individual methods [31–33]. For comparison, the same analysis was carried out on the other family 40 CBMs of known structure.

Availability of supporting data

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession numbers 4ZXK, 4C1W and 4CIX for the apo structure, the 3’SL complex and the 6’SL complex, respectively.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the University of St Andrews and grants provided by the Medical Research Council. We thank Dr David Robinson at the University of Dundee for assistance in the collection and analysis of Octet data.

Abbreviations

- NanA

Neuraminidase A

- CBM

Carbohydrate-Binding Module

- SpCBM

Streptococcus pneumoniae NanA CBM

- 3’SL

α2,3-sialyllactose

- 6’SL

α2,6-sialyllactose

- hBMECs

human brain microvascular endothelial cells

- BBB

Blood–brain-barrier

- RMSD

Root Mean Square Deviation

- SPR

Surface Plasmon Resonance

- BLI

Bio-Layer Interferometry

Footnotes

Competing interests

HC and GLT are inventors on a patent held by the University of St Andrews that includes the therapeutic use of SpCBM. LY and JAP declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

GLT conceived and coordinated the study. HC, JAP and LY analyzed the structural and affinity data, prepared figures and wrote the manuscript. HC designed and produced the construct for SpNanA CBM expression. LY expressed, purified, crystallized and determined the X-ray structures of SpNanA CBM. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Lei Yang, Email: ly10@st-andrews.ac.uk.

Helen Connaris, Phone: +44-1334-467257, Email: hc6@st-andrews.ac.uk.

Jane A. Potter, Email: jap7@st-andrews.ac.uk

Garry L. Taylor, Email: glt2@st-andrews.ac.uk

References

- 1.Jedrzejas MJ. Pneumococcal virulence factors: structure and function. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews : MMBR. 2001;65(2):187–207. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.187-207.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pettigrew MM, Fennie KP, York MP, Daniels J, Ghaffar F. Variation in the presence of neuraminidase genes among Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates with identical sequence types. Infect Immun. 2006;74(6):3360–3365. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01442-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manco S, Hernon F, Yesilkaya H, Paton JC, Andrew PW, Kadioglu A. Pneumococcal neuraminidases A and B both have essential roles during infection of the respiratory tract and sepsis. Infect Immun. 2006;74(7):4014–4020. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01237-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tong HH, Blue LE, James MA, DeMaria TF. Evaluation of the virulence of a Streptococcus pneumoniae neuraminidase-deficient mutant in nasopharyngeal colonization and development of otitis media in the chinchilla model. Infect Immun. 2000;68(2):921–924. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.2.921-924.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tong HH, Liu X, Chen Y, James M, Demaria T. Effect of neuraminidase on receptor-mediated adherence of Streptococcus pneumoniae to chinchilla tracheal epithelium. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122(4):413–419. doi: 10.1080/00016480260000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker D, Soong G, Planet P, Brower J, Ratner AJ, Prince A. The NanA neuraminidase of Streptococcus pneumoniae is involved in biofilm formation. Infect Immun. 2009;77(9):3722–3730. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00228-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shakhnovich EA, King SJ, Weiser JN. Neuraminidase expressed by Streptococcus pneumoniae desialylates the lipopolysaccharide of Neisseria meningitidis and Haemophilus influenzae: a paradigm for interbacterial competition among pathogens of the human respiratory tract. Infect Immun. 2002;70(12):7161–7164. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.7161-7164.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen GY, Chen X, King S, Cavassani KA, Cheng J, Zheng X, et al. Amelioration of sepsis by inhibiting sialidase-mediated disruption of the CD24-SiglecG interaction. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(5):428–435. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King SJ, Whatmore AM, Dowson CG. NanA, a neuraminidase from Streptococcus pneumoniae, shows high levels of sequence diversity, at least in part through recombination with Streptococcus oralis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(15):5376–5386. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5376-5386.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uchiyama S, Carlin AF, Khosravi A, Weiman S, Banerjee A, Quach D, et al. The surface-anchored NanA protein promotes pneumococcal brain endothelial cell invasion. J Exp Med. 2009;206(9):1845–1852. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banerjee A, Van Sorge NM, Sheen TR, Uchiyama S, Mitchell TJ, Doran KS. Activation of brain endothelium by pneumococcal neuraminidase NanA promotes bacterial internalization. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12(11):1576–1588. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connaris H, Govorkova EA, Ligertwood Y, Dutia BM, Yang L, Tauber S, et al. Prevention of influenza by targeting host receptors using engineered proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(17):6401–6406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404205111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Rancurel C, Bernard T, Lombard V, Henrissat B. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D233–D238. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu G, Li X, Andrew PW, Taylor GL. Structure of the catalytic domain of Streptococcus pneumoniae sialidase NanA. Acta Crystallogr, Sect F: Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2008;64(Pt 9):772–775. doi: 10.1107/S1744309108024044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu G, Kiefel MJ, Wilson JC, Andrew PW, Oggioni MR, Taylor GL. Three Streptococcus pneumoniae Sialidases: Three Different Products. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011. doi:10.1021/ja110733q. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Hsiao YS, Parker D, Ratner AJ, Prince A, Tong L. Crystal structures of respiratory pathogen neuraminidases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;380(3):467–471. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boraston AB, Ficko-Blean E, Healey M. Carbohydrate recognition by a large sialidase toxin from Clostridium perfringens. Biochemistry. 2007;46(40):11352–11360. doi: 10.1021/bi701317g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu G, Potter JA, Russell RJ, Oggioni MR, Andrew PW, Taylor GL. Crystal structure of the NanB sialidase from Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Mol Biol. 2008;384(2):436–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo Y, Li SC, Chou MY, Li YT, Luo M. The crystal structure of an intramolecular trans-sialidase with a NeuAc alpha2--3Gal specificity. Structure. 1998;6(4):521–530. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moustafa I, Connaris H, Taylor M, Zaitsev V, Wilson JC, Kiefel MJ, et al. Sialic acid recognition by Vibrio cholerae neuraminidase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(39):40819–40826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404965200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Connaris H, Crocker PR, Taylor GL. Enhancing the receptor affinity of the sialic acid-binding domain of Vibrio cholerae sialidase through multivalency. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(11):7339–7351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807398200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Govorkova EA, Baranovich T, Marathe BM, Yang L, Taylor MA, Webster RG, et al. Sialic acid-binding protein Sp2CBMTD protects mice against lethal challenge with emerging influenza A (H7N9) virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(3):1495–1504. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04431-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu H, Naismith JH. A simple and efficient expression and purification system using two newly constructed vectors. Protein Expr Purif. 2009;63(2):102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Method Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40(Pt 4):658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67(Pt 4):235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53(Pt 3):240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen VB, Arendall WB, 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 1):12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qin S, Zhou HX. meta-PPISP: a meta web server for protein-protein interaction site prediction. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(24):3386–3387. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen H, Zhou HX. Prediction of interface residues in protein-protein complexes by a consensus neural network method: test against NMR data. Proteins. 2005;61(1):21–35. doi: 10.1002/prot.20514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang S, Zhang C, Liu S, Zhou Y. Protein binding site prediction using an empirical scoring function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(13):3698–3707. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neuvirth H, Raz R, Schreiber G. ProMate: a structure based prediction program to identify the location of protein-protein binding sites. J Mol Biol. 2004;338(1):181–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(18):10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schrodinger L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3r1. 2010.