Abstract

Background

Research on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among older adult cancer survivors is mostly confined to breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung cancer, which account for 63% of all prevalent cancers. Much less is known about HRQOL in the context of less common cancer sites.

Methods

We examined HRQOL using the Short-Form-36 v1 (SF-36) and Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12) in selected cancers (kidney, bladder, pancreas, upper gastrointestinal, oral cavity & pharynx, uterine, cervical, thyroid, melanoma, chronic leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and multiple myeloma) and individuals without cancer using data linked from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) cancer registry system and the Medicare Health Outcomes Survey (MHOS). We calculated scale scores, physical and mental component summary (PCS and MCS) scores, and a preference-based score (SF-6D/ VR-6D) adjusted for socio-demographic characteristics and other chronic conditions. We considered a 3-point difference on the scale scores and a 2-point on PCS/MCS as minimally important differences.

Results

Data from 16,095 cancer survivors and 1,224,529 individuals without a history of cancer were included. Results indicate noteworthy deficits in physical health status. Mental health was comparable, although role limitations due to emotional problems and social functioning scale scores were worse for most cancer sites than for those without cancer. Survivors of multiple myeloma and pancreatic malignancy reported the lowest scores, with PCS/MCS scores 1 standard deviation or more below that of individuals without cancer.

Conclusion

HRQOL surveillance efforts reveal poor health outcomes among many older adults, specifically survivors of multiple myeloma and pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: Quality of life, neoplasms, epidemiology, older adult, rare diseases

Background

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) measures can provide important information to clinicians on treatment sequelae and may guide treatment decision-making.1 HRQOL assessment offers insights that may represent or complement primary outcomes, provide information about the patient’s experience of treatment, identify subgroups for further monitoring,2 and suggest approaches to tailoring and targeting patient-centered interventions.1 In addition to monitoring HRQOL in clinical trials, surveillance of HRQOL and predictive modeling of trends over time can yield important information about disease burden and its correlates.3 The importance of outcomes surveillance research in geriatric populations is underscored by the fact that older cancer patients tend to weigh HRQOL more importantly than survival gains in making decisions about cancer treatment.4

Most studies of HRQOL among cancer patients and survivors have been limited to breast cancer,5 and to a lesser extent, individuals with prostate,6 colorectal,7 and lung cancer, 8, 9 and even fewer studies have examined HRQOL among older long-term survivors.10 For example, previous HRQOL research found significantly lower vitality, and physical and emotional role functioning among individuals with prostate cancer,6 and colorectal cancer survivors reported immediate declines in physical functioning following surgery.7 Given that together these four cancer sites represent approximately 63% of prevalent cancer cases in the 65 and over population,11 this emphasis is unsurprising. However, much less is known about the HRQOL experiences of individuals with one of the less common malignancies. Such information could generate hypotheses for continued observational research and direct the development of programs, services, or intervention research to improve clinical care outcomes.12

We examined the HRQOL of older individuals who have been diagnosed with one of these less common cancers using data from U.S. population-based cancer registries linked to a patient-reported outcomes (PROs) survey in individuals aged 65 and over. HRQOL in respondents with these cancers was compared to participants with no history of cancer.

Methods

This study analyzed data derived from a linkage of the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) national cancer registry system and the Medicare Health Outcomes Survey (MHOS). The SEER-MHOS dataset includes PROs and cancer registry information from a nationwide sample of individuals 65 and older enrolled in Medicare Advantage Organizations (managed care health plans). The MHOS is an ongoing quality monitoring effort to collect PROs by the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare (CMS) that has been recruiting multiple cohorts since 1998. Individuals enrolled in participating Medicare Advantage Organizations are randomly sampled by health plans, administered the survey by mail or telephone, and then re-surveyed two-years later.13, 14 The National Cancer Institute and CMS manage the linked dataset as an open-access collaborative resource, and external investigators can apply to access the data (http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/seer-mhos/).

Sample

Ten cohorts, incepted beginning in 1998 and ending in 2009, were included in the study sample. For cancer survivors, data from the first survey following diagnosis were incorporated into analysis. For individuals without cancer, data from the first survey were used. Response rates ranged from 63–72% across study years.14

The less common cancer sites included in this analysis were selected if (1) they were a malignancy other than breast, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer; and (2) the SEER-MHOS data set included at least 100 cases for any given site (across all 10 cohorts). We refer to these cancer types as “uncommon cancers,” rather than “rare cancers,” as these sites may exceed reported criteria for rare diseases.15 The sites chosen for the current study included: melanoma of the skin, non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), multiple myeloma, chronic leukemias (which include chronic myeloid leukemia [CML] and chronic lymphocytic leukemia [CLL]) , and cancers of the uterus, cervix, ovaries, kidney and renal pelvis, urinary bladder, oral cavity and pharynx, upper gastrointestinal tract (stomach and esophagus), thyroid, or pancreas. Only first primary diagnoses were included in the current analysis. Individuals with any history of cancer are referred to as “cancer survivors.”

Individuals who participate in the MHOS survey give informed consent. SEER-MHOS linked data are considered to be a limited dataset, exempt from additional requirements of obtaining informed consent by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. The HIPAA requirements mandate that investigators sign a data use agreement prior to receiving the data, which allows for the release of the SEER-MHOS data without obtaining authorization from survey respondents.

Measures

For cohorts 1–6, the MHOS assessed HRQOL using the SF-36® Survey, Version 1.16 We calculated the standard eight scale scores (physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, bodily pain, general health perceptions, emotional well-being, vitality, social functioning, and role limitations due to emotional problems) and two summary scores (physical health and mental health). The scores are normalized to the general U.S. population using a T-score metric, with a mean score of 50 and a standard deviation of 10; higher scores indicating better HRQOL. A 2 point (0.20 of a standard deviation) difference on the Mental Component Summary (MCS) and Physical Component Summary (PCS) scores and a 3 point (0.30 of a standard deviation) difference in scale scores represents a minimally important difference (MID).17 We also estimated the SF-6D, a health utility score for the SF-36.18 The SF-6D score ranges from 0 to 1 where full health (no impairments or limitations) is 1 and a health state equivalent to death is zero. The MHOS administers replaced the SF-36 with the Veterans RAND 12-item Health Survey (VR-12) in 2006, beginning with cohorts 7 and 8. The VR-12 yields physical and mental health summary scores and a health utility score, the VR-6D, that are strongly correlated with the SF-36 counterparts, the PCS, MCS, and SF-6D.18 The MID for the SF-6D/VR-6D was considered to be 0.03 on the 0–1 scale.19

Statistical Analysis

HRQOL scores were estimated for all cancer sites and for individuals without a history of cancer. Mean scores were calculated using multivariable linear regression models and the predictive-margins method20 with demographic and clinical covariates fixed at zero.21,22 We adjusted for age at first cancer diagnosis, months from first cancer diagnosis to survey (cancer survivors only),whether a participant had been diagnosed with multiple cancers, gender, education (6 categories: 8th grade or less, some high school, high school graduate, some college, 4-year college graduate, more than a 4-year degree) marital status (married, widowed, otherwise not married), age (at diagnosis or first interview for individuals without cancer), race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Non-Hispanic Asian, Non-Hispanic American Indian, Hispanic, or other), household income (<$10,000, $10,000-$19,999, $20,000-$29,999, $30,000-$39,999, $40,000-$49,999, $50,000-$79,999, $80,00+, or unknown), and whether a proxy completed the survey. We also adjusted for study cohort year and mode of administration (telephone or mail). Finally, we adjusted for ever being diagnosed with each the following chronic medical conditions (hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, other heart conditions, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis of the hip or knee, arthritis of the hand or wrist, sciatica, or diabetes) similar to previously published work using SEER-MHOS data.23 Only cases with non-missing data were included in the analyses. Analyses were conducted using the Statistical Analysis Software 9.3 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC).

Results

A total of 16,095 cancer survivors and 1,224,549 individuals without a history of cancer were included in the current study (Table 1). The three most common malignancies were bladder cancer, melanoma, and uterine cancer. Among cancer survivors, the mean age at first diagnosis ranged from 55.5 years (SD±11.7) for participants with cervical cancer to 72.4 years for participants with multiple myeloma (SD±7.8) and pancreatic cancer (SD±8.5). For non-gender specific malignancies, the proportion of participants who were female ranged from 23.1% (bladder) to 72.9% (thyroid). Mean time from diagnosis also varied across cancer types, ranging from 37 months for pancreatic cancer (SD±55.6) to 217 months (SD±110.4) for cervical cancer, consistent with the distinct natural history of these malignancies.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Cancer Site | Age | Gender | Diagnosis-Survey Months |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean(SD) | Median | Female(%) | Mean(SD) | Median | |

| No history of cancer | 1,224,549 | 74.8(6.7) | 74 | 59.7 | - | - |

| Bladder | 3195 | 70.1(8.9) | 70 | 23.1 | 86.2(76.7) | 65 |

| Melanoma | 3019 | 68.8(9.4) | 69 | 40.3 | 90.7(81.3) | 69 |

| Uterus | 2558 | 65.8(9.3) | 66 | 100 | 131.9(98.5) | 113 |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 1563 | 69.7(9.1) | 70 | 50.9 | 75.9(74.2) | 53 |

| Kidney | 1120 | 68.9(8.7) | 69 | 42.3 | 76.7(75.0) | 52 |

| Cervix | 1016 | 55.5(11.7) | 55 | 100 | 216.7(110.4) | 214 |

| Oral cavity & Pharynx | 942 | 67.7(9.0) | 68 | 40.0 | 92.9(83.7) | 71 |

| Thyroid | 586 | 63.0(10.8) | 64 | 72.9 | 132.9(110.0) | 106 |

| Ovary | 568 | 65.7(10.2) | 66 | 100 | 113.0(98.0) | 88 |

| Upper Gastrointestinal | 530 | 71.1(8.2) | 70 | 40.4 | 63.7(69.5) | 37 |

| Chronic Leukemia | 505 | 71.8(8.2) | 72 | 44.8 | 65.6(66.5) | 42 |

| Multiple Myeloma | 302 | 72.4(7.8) | 73 | 48.7 | 43.7(50.4) | 24 |

| Pancreas | 191 | 72.4(8.5) | 71 | 56.5 | 37.2(55.6) | 13 |

Age at first cancer diagnosis or at first survey (no cancer)

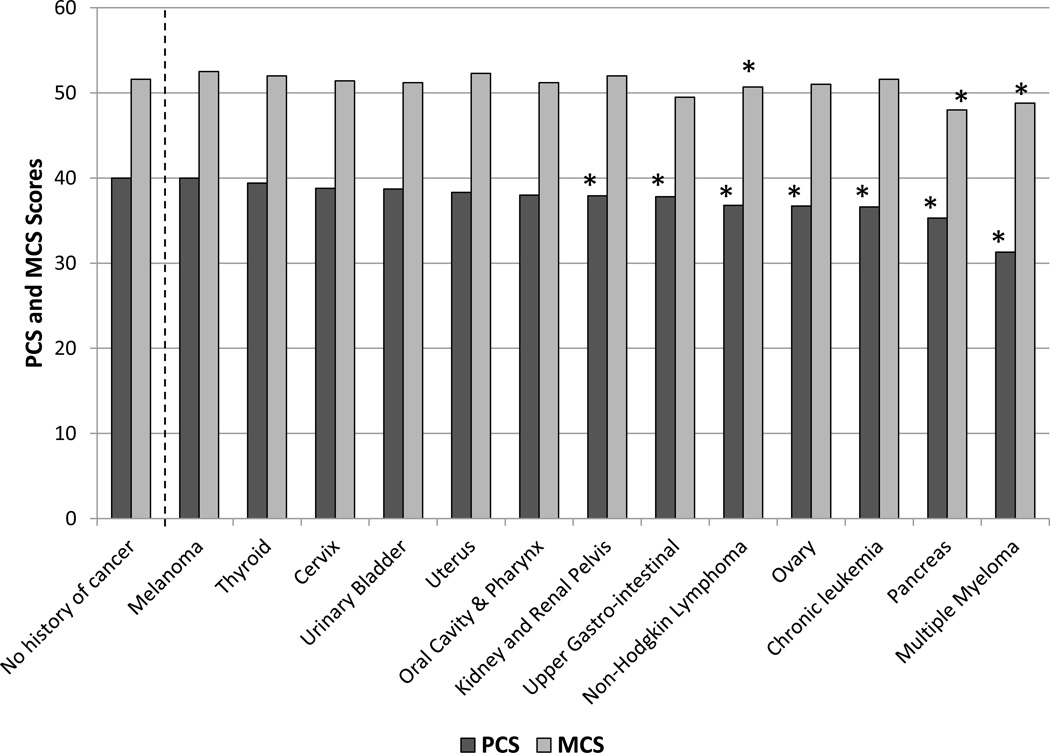

The means and 95% confidence intervals of the PCS, MCS and SF-6D/VR-6D scores, adjusted for covariates, are presented in Table 2 by cancer type. Most PCS scores were lower among cancer survivors than individuals without cancer. However, differences in MCS scores between individuals without cancer and those with most of the cancer did not exceed the MID for a majority of sites. The lowest PCS scores were reported by survivors of multiple myeloma (31.3), pancreatic cancer (35.3), and thyroid cancer (36.7), compared to individuals without cancer (40.5). The lowest MCS scores were reported by survivors of pancreatic cancer (48.0) multiple myeloma (48.8), and ovarian cancers (49.5), compared to individuals without cancer (52.1). Figure 1 shows the mean PCS and MCS scores by cancer site and for individuals without cancer, with stars indicating differences between specific cancer sites and individuals without cancer exceeded the MID threshold. The cancer sites with individuals reporting SF-6D/VR-6D scores exceeding 0.03 of a SD (compared to individuals without cancer) included all but melanoma. Survivors with multiple myeloma reported the lowest mean SF-6D/VR-6D scores (0.63), a 0.10 point difference from individuals without cancer.

Table 2.

Physical and Mental Component Scores and Health Utility (SF-6D/VR-6D Score).*

| PCS† | MCS† | SF-6D/VR-6D‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (95% CI) | N | Mean (95% CI) | N | Mean(95% CI) | |

| No history of cancer | 815,362 | 40.5(40.5–40.5) | 811106 | 52.1(52.1–52.2) | 765,773 | 0.73(0.73–0.73) |

| Bladder | 2,135 | 38.7(38.2,39.1) | 2,122 | 51.2(50.7,51.6) | 2,035 | 0.70(0.69,0.70) |

| Melanoma | 2,174 | 40.0(39.5,40.5) | 2,164 | 52.5(52.1,52.9) | 2,077 | 0.71(0.71,0.72) |

| Uterus | 1,651 | 38.31(37.8,38.9) | 1,640 | 52.3(51.7,52.8) | 1,565 | 0.70(0.69,0.71) |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 1,035 | 36.8(36.2,37.5) | 1,034 | 50.7(50.1,51.4) | 985 | 0.68(0.67,0.69) |

| Kidney | 768 | 37.9(37.2,38.7) | 762 | 52.0(51.2,52.7) | 727 | 0.70(0.69,0.70) |

| Cervix | 649 | 38.8(37.9,39.6) | 645 | 51.4(50.5,52.2) | 615 | 0.70(0.69,0.71) |

| Oral cavity & Pharynx | 635 | 38.0(37.2,38.8) | 628 | 51.2(50.4,52.0) | 580 | 0.69(0.68,0.70) |

| Thyroid | 405 | 39.4(38.4,40.4) | 402 | 52.0(51.1,52.9) | 386 | 0.70(0.69,0.71) |

| Ovary | 368 | 36.7(35.6,37.8) | 364 | 51.0(49.9,52.1) | 344 | 0.68(0.67,0.69) |

| Upper Gastro-intestinal | 326 | 37.8(36.6,39.0) | 325 | 49.5(48.3,50.8) | 311 | 0.68(0.67,0.69) |

| Chronic Leukemia | 347 | 36.6(35.5,37.8) | 344 | 51.6(50.6,52.7) | 319 | 0.69(0.67,0.70) |

| Multiple Myeloma | 198 | 31.3(29.8,32.9) | 198 | 48.8(47.3,50.3) | 192 | 0.63(0.62,0.65) |

| Pancreas | 126 | 35.3(33.2,37.3) | 126 | 48.0(45.8,50.1) | 120 | 0.65(0.63,0.68) |

Scores are adjusted for  , whether cancer patient had a multiple cancers (yes/no), continuous age at first cancer dx or first survey if no cancer, 12 chronic medical conditions, education, gender, marital status, race/ethnicity, income, whether or not a proxy completed the survey, cohort 1 vs others, and mode of administration (mail or telephone).

, whether cancer patient had a multiple cancers (yes/no), continuous age at first cancer dx or first survey if no cancer, 12 chronic medical conditions, education, gender, marital status, race/ethnicity, income, whether or not a proxy completed the survey, cohort 1 vs others, and mode of administration (mail or telephone).

Bolded scores represent a minimally important difference (2.0 or greater) between the mean component score (PCS or MCS) for cancer survivors vs. individuals without cancer.

Bolded scores represent a minimally important difference (0.03 or greater) between the mean utility metric (SF6D/VR6D) for cancer survivors vs. individuals without cancer.

Figure 1.

Covariate-adjusted mean scores for all 8 scales are presented in Table 3 (4 “physical health” scales) and Table 4 (4 “mental health” scales). For individuals with the greatest impairments in PCS and MCS (respondents with multiple myeloma, chronic leukemias, NHL, and tumors of the pancreas, ovary or upper gastrointestinal tract), deficits were reflected across several scales, particularly physical functioning, social and physical role functioning, vitality, and appraisals of general health. Mental health scale scores were mostly comparable to those without cancer for all of these cancer sites. Bodily pain, physical role functioning, and vitality were prominent concerns for respondents with multiple myeloma and pancreatic cancer. The largest between-group differences were observed in three scales: physical functioning, role physical, and general health, and exceeded the MID of 3 points for several sites. The lowest mean scores for physical functioning were reported by participants with multiple myeloma (34.4)compared to no cancer (41.0). The most significant limitations in role function due to physical health problems were reported by respondents with multiple myeloma (28.9), and cancers of the pancreas (31.4) or ovaries (34.5) compared to no cancer (39.9). The lowest mean scale scores for general health were seen in survivors of multiple myeloma (36.9) and pancreatic cancer (39.3), compared to individuals without cancer (46.9). In general, survivors reported only small differences, compared to individuals without cancer, on the scales that are considered to reflect mental health, specifically the mental health and role limitations due to emotional problems scales. However, survivors with multiple myeloma, and pancreatic or upper gastrointestinal malignancies, compared to those without cancer, reported significant limitations in role function because of emotional problems (multiple myeloma [37.3], upper gastro-intestinal [39.7]), compared to individuals without cancer [45.3]).

Table 3.

SF-36 physical health scale scores and 95% confidence intervals.*

| Physical Functioning† | Role Physical† | Bodily Pain† | General Health† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (95% CI) | N | Mean (95% CI) | N | Mean (95% CI) | N | Mean (95% CI) | |

| No history of cancer | 488,739 | 41.7(41.7–41.7) | 482,639 | 40.7(40.6–40.7) | 485,119 | 46.6(46.6–46.7) | 489,890 | 46.9(46.8–46.9) |

| Bladder | 1,296 | 40.5(39.9,41.2) | 1,280 | 38.5(37.6,39.4) | 1,290 | 46.1(45.5,46.6) | 1,302 | 45.0(44.4,45.5) |

| Melanoma | 1,157 | 41.9(41.3,42.5) | 1,148 | 40.4(39.5,41.3) | 1,150 | 46.7(46.1,47.2) | 1,163 | 46.9(46.3,47.4) |

| Uterus | 1,033 | 40.0(39.3,40.7) | 1,021 | 37.5(36.4,38.5) | 1,023 | 45.8(45.1,46.4) | 1,036 | 45.7(45.1,46.3) |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 600 | 38.5(37.6,39.3) | 588 | 35.5(34.2,36.8) | 600 | 45.7(44.9,46.5) | 601 | 42.3(41.5,43.1) |

| Kidney | 439 | 40.4(39.5,41.4) | 433 | 38.0(36.5,39.4) | 435 | 44.4(43.4,45.3) | 440 | 44.1(43.2,45.0) |

| Cervix | 336 | 40.3(39.2,41.5) | 331 | 37.9(36.0,39.8) | 331 | 46.2(45.1,47.3) | 336 | 45.8(44.8,46.9) |

| Oral cavity & Pharynx | 388 | 39.5(38.4,40.6) | 374 | 37.3(35.7,38.8) | 378 | 45.8(44.8,46.9) | 388 | 44.0(43.1,45.0) |

| Thyroid | 183 | 41.5(40.1,42.9) | 178 | 38.0(35.7,40.3) | 181 | 45.9(44.5,47.2) | 184 | 46.2(44.9,47.5) |

| Ovary | 208 | 39.0(37.5,40.5) | 204 | 34.5(32.3,36.7) | 204 | 45.2(43.9,46.6) | 209 | 42.7(41.3,44.1) |

| Upper Gastro-intestinal | 191 | 38.8(37.2,40.4) | 190 | 35.2(32.9,37.5) | 190 | 45.9(44.2,47.3) | 191 | 42.2(40.8,43.7) |

| Chronic Leukemia | 189 | 40.1(38.6,41.5) | 186 | 37.6(35.2,40.0) | 186 | 45.6(44.2,46.9) | 189 | 42.1(40.7,43.6) |

| Multiple Myeloma | 110 | 34.4(32.3,36.4) | 110 | 28.9(26.3,31.6) | 110 | 40.0(38.0,42.1) | 110 | 36.9(35.0,38.9) |

| Pancreas | 65 | 38.1(35.2,40.9) | 65 | 31.4(27.7,35.2) | 65 | 43.2(40.4,46.1) | 65 | 39.3(36.8,41.7) |

Scores are adjusted for  , whether cancer patient had a multiple cancers (yes/no), continuous age at first cancer diagnosis or first survey if no cancer, 12 chronic medical conditions, education, gender, marital status, race/ethnicity, income, whether or not a proxy completed the survey, cohort 1 vs. others, and mode of administration (mail or telephone).

, whether cancer patient had a multiple cancers (yes/no), continuous age at first cancer diagnosis or first survey if no cancer, 12 chronic medical conditions, education, gender, marital status, race/ethnicity, income, whether or not a proxy completed the survey, cohort 1 vs. others, and mode of administration (mail or telephone).

Bolded scores represent a minimally important difference (3.0+) between the mean subscale score for cancer survivors vs. individuals without cancer.

Table 4.

SF-36 mental health scale scores and 95% confidence intervals.*

| Vitality† | Social Functioning† | Role Emotional† | Mental Health† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (95% CI) | N | Mean (95% CI) | N | Mean (95% CI) | N | Mean (95% CI) | |

| No history of cancer | 485,005 | 49.4(49.3–49.4) | 485,525 | 48.0(48.0–48.0) | 481,275 | 45.2(45.2–45.3) | 485,190 | 51.4(51.4–51.4) |

| Bladder | 1,289 | 48.1(47.5,48.7) | 1,289 | 46.3(45.6,46.9) | 1,276 | 44.2(43.2,45.2) | 1,289 | 50.6(50.0,51.1) |

| Melanoma | 1,152 | 49.6(49.0,50.2) | 1,153 | 47.6(47.0,48.3) | 1,147 | 45.7(44.8,46.7) | 1,153 | 51.8(51.3,52.3) |

| Uterus | 1,023 | 48.3(47.6,49.0) | 1,025 | 46.9(46.2,47.7) | 1,019 | 44.8(43.6,46.0) | 1,023 | 51.7(51.1,52.3) |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 598 | 46.4(45.6,47.2) | 600 | 45.0(44.1,45.9) | 591 | 42.5(41.1,44.0) | 599 | 49.9(49.1,50.7) |

| Kidney | 435 | 47.2(46.2,48.2) | 435 | 45.8(44.7,46.9) | 432 | 42.5(40.8,44.2) | 435 | 51.2(50.2,52.1) |

| Cervix | 332 | 48.7(46.9,49.2) | 331 | 46.8 (45.5,48.0) | 331 | 43.8 (41.7,45.9) | 332 | 50.4 (49.3,51.6) |

| Oral cavity & Pharynx | 381 | 47.2(46.2,48.3) | 380 | 45.6 (44.5,46.8) | 372 | 44.3 (42.6,46.0) | 381 | 50.1 (49.1,51.0) |

| Thyroid | 180 | 48.5(47.1,50.0) | 181 | 46.5 (45.0,47.9) | 179 | 44.0 (41.6,46.4) | 180 | 52.2 (50.9,53.6) |

| Ovary | 206 | 45.7(44.2,47.3) | 206 | 43.5 (41.9,45.1) | 201 | 43.2 (40.7,45.6) | 206 | 50.2 (48.9,51.6) |

| Upper Gastro-intestinal | 190 | 46.1(44.6,47.6) | 190 | 43.4 (41.6,45.2) | 188 | 39.7 (36.9,42.5) | 190 | 48.7 (47.1,50.3) |

| Chronic Leukemia | 186 | 46.3(44.8,47.9) | 186 | 44.9(43.3,46.5) | 184 | 44.6(42.0,47.2) | 186 | 50.8(49.4,52.2) |

| Multiple Myeloma | 110 | 42.5(40.7,44.4) | 110 | 41.1(38.8,43.4) | 110 | 37.3(33.7,41.0) | 110 | 49.5(47.5,51.5) |

| Pancreas | 65 | 45.3(42.7,47.9) | 65 | 41.4(38.4,44.5) | 65 | 40.3(35.5,45.2) | 65 | 50.4(47.7,53.0) |

Scores are adjusted for  , whether cancer patient had a multiple cancers (yes/no), continuous age at first cancer diagnosis or first survey if no cancer, 12 chronic medical conditions, education, gender, marital status, race/ethnicity, income, whether or not a proxy completed the survey, cohort 1 vs. others, and mode of administration (mail or telephone).

, whether cancer patient had a multiple cancers (yes/no), continuous age at first cancer diagnosis or first survey if no cancer, 12 chronic medical conditions, education, gender, marital status, race/ethnicity, income, whether or not a proxy completed the survey, cohort 1 vs. others, and mode of administration (mail or telephone).

Bolded scores represent a minimally important difference (3.0+) between the mean subscale score for cancer survivors vs. individuals without cancer.

Discussion

In this large, population-based study of health outcomes in older adults diagnosed with selected cancers, we found that the PCS was markedly lower in survivors of cancers of the oral cavity, uterus, kidney, upper gastrointestinal tract, ovaries and pancreas, and among survivors of NHL, chronic leukemias, and multiple myeloma, compared to individuals without cancer. The largest differences in HRQOL scales reported between survivors and controls were among survivors of pancreatic cancer (12 points) and multiple myeloma (15 points). Other studies of older adults with and without cancer have shown similar patterns.24–26 The two scales with the biggest score deficits between cancer survivors and individuals without a history of cancer were physical functioning and role limitations due to physical health, findings that have been demonstrated in other studies of older cancer survivors.25, 27–31

Except for those respondents with pancreatic cancer and multiple myeloma, bodily pain scores were not significantly different between cancer survivors and individuals without cancer in the adjusted analyses. These results are surprising, given findings from other studies that reflect pain. The results may in part reflect between-study differences in the older adult population sampled (e.g., ambulatory or not) and cancer sites under investigation. A study of cognitively intact nursing home residents, Drageset et al.28 found that residents with cancer reported worse pain than residents without cancer. Cancer-related pain has been shown to be associated with other aspects of HRQOL including impairments in physical and emotional functional status,32 identifying and addressing pain among cancer survivors is critically important to reduce suffering.

We observed that for 8 of the cancer types, MCS was not notably different from those without cancer, a finding documented by previous literature.26 Exceptions include individuals diagnosed with bladder cancer, NHL, pancreatic cancer, upper gastrointestinal cancer, and multiple myeloma. Scale scores also revealed significant deficits in role limitations due to emotional problems and mental health among respondents with multiple myeloma, or an upper gastrointestinal tract or pancreas tumor.

SF-6D/VR-6D score examination allow for a rapid comparison of health utilities among cancer types, and in the current study our analysis indicated that individuals with ovarian cancer (0.67), pancreatic cancer (0.65) and multiple myeloma (0.63) reported the lowest scores compared to individuals without cancer (0.73). These scores are comparable to those reported for Medicare Advantage enrollees who reported other chronic conditions, including stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma, and coronary artery disease.22 The SF-6D/VR-6D scores for comparisons to be made over time among individuals and across disease sites and can be used to calculate quality-adjusted life years, a useful metric for health evaluation.22

Deficits in HRQOL scores across the PCS, MCS, SF-6D/VR-6D were greatest for individuals with multiple myeloma and pancreatic cancer. Previous research on PROs is particularly limited for multiple myeloma, likely due to its relatively rare incidence and the difficulty of recruiting sufficient sample size. The disease burden, as evidenced by the current study and a few other published reports in multiple myeloma33 and pancreatic cancer,34 suggests the need for research to identify factors that contribute to inferior outcomes among respondents with these malignancies.

Our study leverages the strengths inherent in the SEER-MHOS data resource, specifically its large sample size, which enables reporting of outcomes in survivors of less common cancers, and its health-plan based sampling approach, which covers wide and diverse geographic areas. The large sample size, however, was still not large enough to include individuals with even less common cancers (eg. esophageal and liver) which is a constraint of population-based research in general. One limitation of the dataset is the lack of cancer-specific measures of HRQOL which may be more sensitive to the impact of cancer on HRQOL. However the SF-36 and VR-12 are widely used instruments that have been evaluated in multiple disease and treatment contexts,35 and their use in this sample permits comparisons with SEER-MHOS subgroups, including those without cancer, and those with specific comorbid conditions. Other measures in MHOS, such as the HEDIS® effectiveness of care measures36 including fall risk management and management of urinary incontinence, may be able to provide information about other aspects of patient experience and should be considered in future PRO studies. In addition, cancer survivors included in the current analysis ranged widely in time since diagnosis, and this heterogeneity should be considered carefully in future analyses of the SEER-MHOS dataset.

Another limitation of the SEER-MHOS data is the lack of data on Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, where the majority of Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled.14 Prior research has demonstrated that Medicare Advantage enrollees may be healthier than fee-for-service Medicare enrollees who tend to report more risk factors and lower HRQOL.37 Although the SEER registry covers approximately 27% of the population of Medicare Advantage enrollees,38 it does not include certain regions, for example the states of Florida and Minnesota, which have high managed care penetration. At the same time, Medicare Advantage plans are not represented in all SEER regions, thus, important geographical variations may be missed.14 In addition, SEER-MHOS data are limited by the availability of treatment data in the SEER cancer registry: data on first course of therapy for surgery and radiation are considered to be generally reliable, but data on chemotherapy and hormonal therapy are not reported due to under-ascertainment. Thus, analyses by cancer sites that are predominantly treated by these modalities must acknowledge this limitation. Additional limitations common to survey research are healthy participant bias and the inability to draw causal inferences from cross-sectional data.

Impairments in HRQOL in survivors with uncommon cancers likely reflect a myriad of factors including the sequelae of disease and treatment, psychosocial factors such as social isolation, and the impact of comorbidities and financial strain. The experience of having a serious and chronic illness in the context of aging may partially account for inferiorities in HRQOL.25 Future studies of SEER-MHOS data and other population-based data resources comprised of data from cancer survivors can be used to identify the socio-demographic, biological, and clinical factors that may contribute to health status impairments, both across disease sites and in particular subgroups with one of these less common cancers. Moreover, future research should make use of the longitudinal data available in SEER-MHOS, examining changes in health status over time among individuals with specific cancer types.39 In addition, examining healthcare provider characteristics could help inform which contexts patient-centered interventions might be most successful. Studies comparing specific age groups across the cohorts could help determine if there are distinct patterns of health status decline based on age strata (ie. young-old vs. old-old) at diagnosis. The measurement and surveillance of these PROs should continue to inform patient-centered interventions, including those for patients with less common cancers.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Marie Topor, Gigi Yuan, and Dennis Buckman for assistance with data analysis.

Funding: Ron D. Hays was supported in part by grants from the NIA (P30-AG021684) and the NIMHD (P20MD000182).

Footnotes

Disclaimer: Findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Cancer Institute or the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. There are no financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Trask PC, Hsu MA, McQuellon R. Other paradigms: health-related quality of life as a measure in cancer treatment: its importance and relevance. Cancer J. 2009;15:435–440. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181b9c5b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Au HJ, Ringash J, Brundage M, et al. Added value of health-related quality of life measurement in cancer clinical trials: the experience of the NCIC CTG. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10:119–128. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conway PH, Mostashari F, Clancy C. The future of quality measurement for improvement and accountability. JAMA. 2013;309:2215–2216. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wedding U, Pientka L, Hoffken K. Quality-of-life in elderly patients with cancer: a short review. European Journal of Cancer. 2007;43:2203–2210. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;27:32. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-27-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eton DT, Lepore SJ. Prostate cancer and health-related quality of life: a review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology. 2002;11:307–326. doi: 10.1002/pon.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanoff HK, Goldberg RM, Pignone MP. A systematic review of the use of quality of life measures in colorectal cancer research with attention to outcomes in elderly patients. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2007;6:700–709. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2007.n.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pat K, Dooms C, Vansteenkiste J. Systematic review of symptom control and quality of life in studies on chemotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer: how CONSORTed are the data? Lung Cancer. 2008;62:126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siddiqui F, Konski AA, Movsas B. Quality-of-life concerns in lung cancer patients. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10:667–676. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitzsimmons D, Gilbert J, Howse F, et al. A systematic review of the use and validation of health-related quality of life instruments in older cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer. 2009;45:19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parry C, Kent EE, Mariotto AB, Alfano CM, Rowland JH. Cancer survivors: a booming population. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2011;20:1996–2005. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gatta G, Ciccolallo L, Kunkler I, et al. Survival from rare cancer in adults: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:132–140. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70471-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clauser SB, Haffer SC. SEER-MHOS: a new federal collaboration on cancer outcomes research. Health Care Financing Review. 2008;29:1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ambs A, Warren JL, Bellizzi KM, Topor M, Haffer SC, Clauser SB. Overview of the SEER--Medicare Health Outcomes Survey linked dataset. Health Care Financing Review. 2008;29:5–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Trama A, Martinez-Garcia C. The burden of rare cancers in Europe. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2010;686:285–303. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9485-8_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hays RD, Farivar SS, Liu H. Approaches and recommendations for estimating minimally important differences for health-related quality of life measures. COPD. 2005;2:63–67. doi: 10.1081/copd-200050663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selim AJ, Rogers W, Qian SX, Brazier J, Kazis LE. A preference-based measure of health: the VR-6D derived from the veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey. Quality of Life Research. 2011;20:1337–1347. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9866-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gandhi PK, Ried LD, Bibbey A, Huang IC. SF-6D utility index as measure of minimally important difference in health status change. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2012;52:34–42. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2012.10114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graubard BI, Korn EL. Predictive margins with survey data. Biometrics. 1999;55:652–659. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hays RD, Spritzer KL. Society for Computers in Psychology. Toronto, Canada: 2013. REcycled SAS® PrEdiCTions (RESPECT) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazis LE, Selim AJ, Rogers W, Qian SX, Brazier J. Monitoring outcomes for the Medicare Advantage program: methods and application of the VR-12 for evaluation of plans. J Ambul Care Manage. 2012;35:263–276. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e318267468f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith AW, Reeve BB, Bellizzi KM, et al. Cancer, comorbidities, and health-related quality of life of older adults. Health Care Financing Review. 2008;29:41–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avis NE, Deimling GT. Cancer survivorship and aging. Cancer. 2008;113:3519–3529. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumann R, Putz C, Rohrig B, Hoffken K, Wedding U. Health-related quality of life in elderly cancer patients, elderly non-cancer patients and an elderly general population. European Journal of Cancer Care (English Language Edition) 2009;18:457–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lazovich D, Robien K, Cutler G, Virnig B, Sweeney C. Quality of life in a prospective cohort of elderly women with and without cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:4283–4297. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koo K, Zeng L, Chen E, et al. Do elderly patients with metastatic cancer have worse quality of life scores? Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012;20:2121–2127. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drageset J, Eide GE, Ranhoff AH. Cancer in nursing homes: characteristics and health-related quality of life among cognitively intact residents with and without cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2012;35:295–301. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31822e7cb8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck SL, Towsley GL, Caserta MS, Lindau K, Dudley WN. Symptom experiences and quality of life of rural and urban older adult cancer survivors. Cancer Nursing. 2009;32:359–369. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181a52533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan LG, Nan L, Thumboo J, Sundram F, Tan LK. Health-related quality of life in thyroid cancer survivors. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:507–510. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31802e3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ingram SS, Seo PH, Sloane R, et al. The association between oral health and general health and quality of life in older male cancer patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53:1504–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green CR, Hart-Johnson T, Loeffler DR. Cancer-related chronic pain: examining quality of life in diverse cancer survivors. Cancer. 2011;117:1994–2003. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mols F, Oerlemans S, Vos AH, et al. Health-related quality of life and disease-specific complaints among multiple myeloma patients up to 10 yr after diagnosis: results from a population-based study using the PROFILES registry. European Journal of Haematology. 2012;89:311–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2012.01831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crippa S, Dominguez I, Rodriguez JR, et al. Quality of life in pancreatic cancer: analysis by stage and treatment. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2008;12:783–793. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0391-9. discussion 793–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson RT, Aaronson NK, Bullinger M, McBee WL. A review of the progress towards developing health-related quality-of-life instruments for international clinical studies and outcomes research. Pharmacoeconomics. 1996;10:336–355. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199610040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bowen SE. Evaluating outcomes of care and targeting quality improvement using Medicare health outcomes survey data. J Ambul Care Manage. 2012;35:260–262. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e31826746ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riley G. Two-year changes in health and functional status among elderly Medicare beneficiaries in HMOs and fee-for-service. Health Services Research. 2000;35:44–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaiser Family Foundation. [accessed June 17, 2013];Total Medicare Advantage (MA) Enrollment. Available from URL: http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/ma-total-enrollment/ [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puts MT, Monette J, Girre V, et al. Quality of life during the course of cancer treatment in older newly diagnosed patients. Results of a prospective pilot study. Annals of Oncology. 2011;22:916–923. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]