Abstract

Neonatal infection is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Increased susceptibility to infection in the neonate is attributed in part to defects in T cell-mediated immunity. A peptide:MHCII (p:MHCII) tetramer-based cell enrichment method was used to test this hypothesis at the level of a single epitope. We found that naïve T cells with TCRs specific for the 2W:I-Ab epitope were present in the thymuses of one-day-old CD57BL/6 mice but were barely detectable in the spleen, likely because each mouse contained very few total splenic CD4+ T cells. By day 7 of life, however, the total number of splenic CD4+ T cells increased dramatically and the frequency of 2W:I-Ab-specific naïve T cells reached that of adult mice. Injection of 2W peptide in CFA into one-day-old mice generated a 2W:I-Ab-specific effector cell population that peaked later than in adult mice and showed more animal-to-animal variation. Similarly, 2W:I-Ab-specific naïve T cells in different neonatal mice varied significantly in generation of Th1, Th2, and follicular helper T cells compared to adult mice. These results suggest that delayed effector cell expansion and stochastic variability in effector cell generation due to an initially small naïve repertoire contribute to defective p:MHCII-specific immunity in neonates.

Introduction

Neonates are more susceptible to infection than older children and adults. Approximately 25% of neonatal mortality worldwide is due to infections, with another 31% due to prematurity, which is often secondary to infection (1). It remains unclear to what degree this is due to neonates having a functionally immature immune system (2, 3).

Previous work has suggested that neonatal immunodeficiency may be related to CD4+ T cells (4). The output of naïve T cells from the thymus is large in neonates creating a situation where recent thymic emigrants (RTEs) make up the majority of T cells in the secondary lymphoid organs of newborns (5). Some studies have suggested that CD4+ RTEs are inherently defective in the capacity to differentiate into IFN-γ-secreting Th1 cells when stimulated through their TCRs (6). In addition, it has been reported that genes within the Th2 locus are hypomethylated in neonates compared to adults, which fits with the observation that neonatal T cells differentiate into Th2 cells more readily than adult T cells (7, 8). While a propensity to make Th2 instead of Th1 responses might explain an infant’s susceptibility to cell-mediated pathogens, other evidence (9–11) indicates that this is not the case.

Another suspected cause of neonatal CD4+ T cell immunodeficiency relates to the timing of expression of TdT, an enzyme that inserts nucleotides into the n-regions of Tcr genes (12). TdT activity has been noted at around 20 weeks gestation in humans, or at day 1–3 in mice (13, 14). Therefore, neonatal T cells have had limited exposure to TdT, and therefore likely contain a less diverse TCR repertoire and a potentially limited capacity to respond to MHC-bound foreign peptides.

Assessment of the functionality of CD4+ T cells from neonates has been impaired by the technical difficulty of detecting the small number of T cells with TCRs specific for any given MHCII-bound foreign peptide epitope (p:MHCII). Recent advances in the use of p:MHCII tetramers and magnetic bead-based cell enrichment, however, have removed this barrier (15, 16). Here we use this new technology to evaluate the number and function of neonatal CD4+ T cells specific for a p:MHCII epitope. The results are consistent with the possibility that immune response abnormalities in the neonate are due to the small size of their pre-immune T cell repertoires.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 (B6) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Mice were housed and bred in specific pathogen-free conditions at the University of Minnesota, and all experiments were conducted in accordance with institutional and federal guidelines.

Peptide Injections

Mice were injected i.p. with 2W peptide (EAWGALANWAVDSA) emulsified in CFA. Adult mice received 50 μg of 2W peptide. Neonatal mice received 2 μg of 2W peptide on day of life 1 or 10 μg on day of life 7–8.

Cell enrichment and flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions of spleens and thymuses were stained for 1 h at room temperature with 2W:I-Ab-streptavidin-PE and 2W:I-Ab-streptavidin-allophycocyanin tetramers, enriched for tetramer bound cells, counted, and labeled with Abs, as previously described (16, 17). In experiments designed to detect transcription factor expression, the cells were then treated with Foxp3 Fixation/Permeabilization buffer (eBioscience) for 1 h at room temperature and subsequently stained for 1 h on ice with Abs against T-bet, Bcl6, ROR-γt, and GATA-3. Cells were passed through an LSRII or Fortessa flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (GraphPad).

Results

Enumeration of p:MHCII-specific CD4+ T cells in neonatal mice

To evaluate the numbers of naïve CD4+ T cells specific for a p:MHCII epitope, we harvested spleens from B6 mice at weekly intervals starting on the first day of life until the time of weaning, and from adult mice >6 than weeks old. Immunologically, a one-day old mouse is similar to a preterm human neonate, and a one-week-old mouse is similar to a full term human infant (13, 14). We detected CD4+ T cells expressing TCRs specific for the immunogenic 2W peptide, which binds to the I-Ab MHC molecule expressed by B6 mice (18). Spleen cells were stained with a pair of 2W:I-Ab tetramers, one labeled with PE and one labeled with allophycocyanin to maximize the TCR-specificity of the assay (17). Anti-fluorochrome magnetic beads were added and the cell suspensions were enriched for tetramer-bound cells on a magnetized column (16). The bound cells were stained with antibodies specific for CD90.2, CD4, CD8, CD44, and a cocktail of non-T cell lineage-specific antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry.

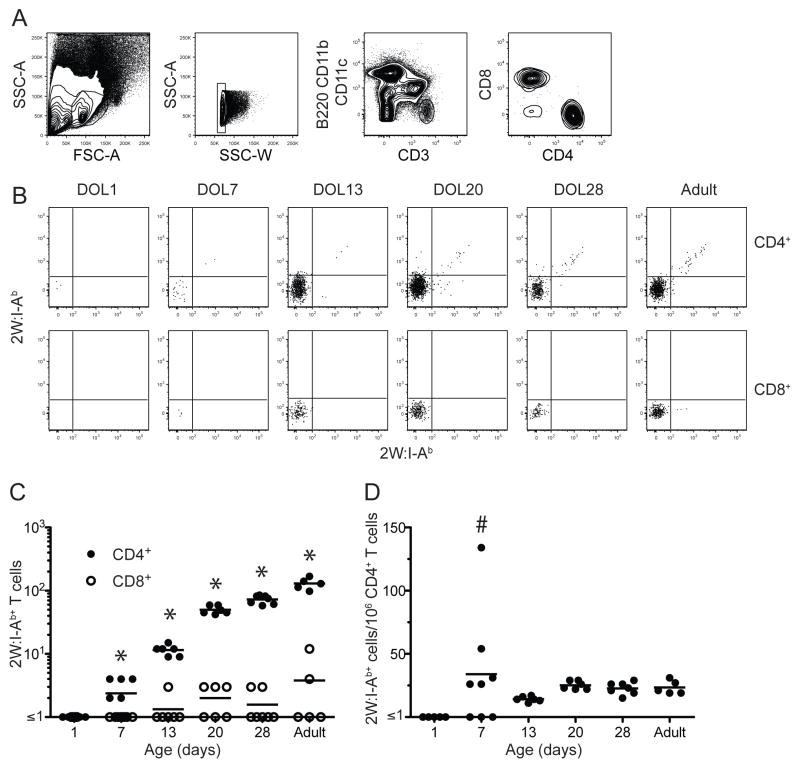

The gating strategy used to identify 2W:I-Ab-specific T cells is shown in Fig. 1A. Cells were initially gated based on lymphocyte size and granularity. Doublets were excluded with a side-scatter area versus side-scatter width gate. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were then identified within the CD90.2+, non-T cell lineage− population. CD4+ T cells that bound to both 2W:I-Ab tetramers were detected in the spleens of adult mice and the majority of these cells had the CD44low naïve phenotype as expected for mice that had not been exposed to this peptide. Very few 2W:I-Ab-specific cells were present in the CD8+ T cell population, indicating that tetramer staining of the CD4+ T cells was TCR-specific (Fig. 1B). Adult mice contained about 200 2W:I-Ab specific CD4+ T cells per spleen at a frequency of about 20 per million total CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1C) as reported in other studies (19).

Figure 1.

Enumeration of 2W:I-Ab-specific cells in the spleen. (A) Flow cytometry plots illustrating the gates used to detect lymphocyte-sized cells (first panel), singlets (second panel) in the spleen expressing CD3 but not non-T lineage-markers (third panel), and either CD4 or CD8 (fourth panel). (B) Representative flow cytometry plots showing 2W:I-Ab-streptavidin-PE (x-axes) versus 2W:I-Ab-streptavidin-allophycocyanin (y-axes) tetramer staining of CD4+ (top row) or CD8+ (bottom row) T cells from the spleens of unimmunized mice at the indicated days of life (DOL). (C) Absolute number of CD4+ (closed circles) or CD8+ (open circles) 2W:I-Ab+ T cells in the spleens of unimmunized mice at the indicated ages. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) between the number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells based on a two-tailed, paired Student’s t test. (D) Frequency of 2W:I-Ab+ CD4+ T cells per million total CD4+ T cells in the spleens of unimmunized mice at the indicated ages. The horizontal lines identify the mean value for each population. The hashtag sign indicates a group containing values that were significantly (p = 0.001) more variable than the corresponding values from adult mice based on an F-test.

2W:I-Ab specific CD4+ T cells were then enumerated in neonatal mice. These cells were undetectable in the spleens of one-day old mice (Fig. 1B and C). The number of splenic 2W:I-Ab-specific CD4+ T cells then rose progressively between days 7, 13, 20 and 28 days of life (Fig. 1C) in parallel with an increase in the total number of CD4+ T cells (data not shown). The frequency of 2W:I-Ab specific CD4+ T cells reached about 20 per million total CD4+ T cells by day of life 7 (Fig. 1D) although more animal-to-animal variation was observed at this time than at later times. These results show that the splenic T cell repertoire in a one-day old mouse may be too small to contain 2W:I-Ab specific CD4+ T cells but then is populated with these cells as the total number of T cells increases with age.

2W:I-Ab-specific CD4+ T cells are present in the neonatal thymus

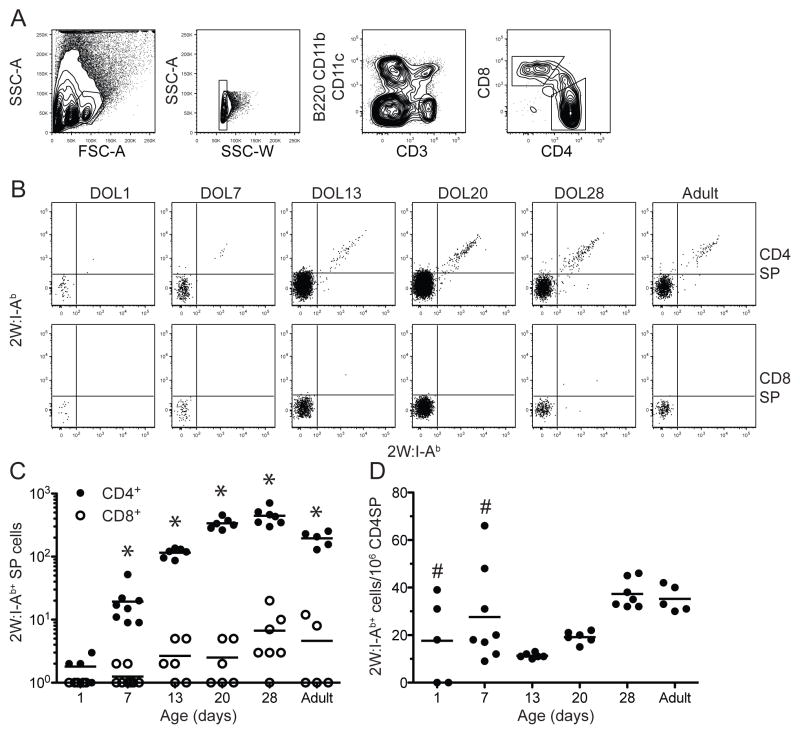

The absence of 2W:I-Ab-specific CD4+ T cells in the spleens of one-day old mice raised the possibility that these cells are not generated in the thymus early in life, perhaps due to a dependence on TdT activity. To test this hypothesis, 2W:I-Ab tetramer-based cell enrichment experiments were performed on thymuses from mice of various ages. CD3high CD4+ CD8− single positive thymocytes (Fig. 2A) were the focus of these studies since these are the cells that survive positive and negative selection and are about to be exported to the secondary lymphoid organs (20). 2W:I-Ab-specific CD4+ CD8− T cells were detected in the thymuses of most one-day old mice. On average, the frequency of 2W:I-Ab-specific CD4+ CD8− T cells in the thymuses of one-day old mice was similar to the ~20 per million CD4+ T cell frequency found in the adult thymus. 2W:I-Ab-specific CD4+ CD8− T cells were detected in the thymuses of all seven-day old mice, again at the frequency observed in the adult thymus. The frequencies of 2W:I-Ab-specific CD4+ CD8− T cells in the thymuses of one- and seven-day old mice were more variable than that of the comparable population in adults (Fig. 2A). These results show that one-day old mice have 2W:I-Ab-specific T cells in the thymus but have not yet exported these cells to the secondary lymphoid organs (21).

Figure 2.

Enumeration of 2W:I-Ab-specific cells in the thymus. (A) Flow cytometry plots illustrating the gates used to detect lymphocyte-sized single cells in the thymus expressing the largest amounts of CD3 but not non-T lineage-markers, and either CD4 or CD8. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots showing 2W:I-Ab-streptavidin-PE (x-axes) versus 2W:I-Ab-streptavidin-allophycocyanin (y-axes) tetramer staining of CD4+ CD8− (CD4SP) (top row) or CD4− CD8+ (CD8SP) (bottom row) thymocytes of mice at the indicated ages. (C) Absolute number of CD4SP (closed circles) or CD8SP (open circles) 2W:I-Ab+ thymocytes in mice at the indicated ages. A statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) between the number of CD4SP and CD8SP thymocytes based on a two-tailed, paired Student’s t test indicated by asterisks was observed at all ages. (D) Frequency of 2W:I-Ab+ CD4SP thymocytes per million total CD4SP thymocytes of mice at the indicated ages. The horizontal lines identify the mean value for each population. Pound signs indicate values that were significantly (p < 0.05) more variable than the corresponding values from adult mice based on an F-test.

Expansion of 2W:I-Ab specific neonatal CD4+ T cells following immunization

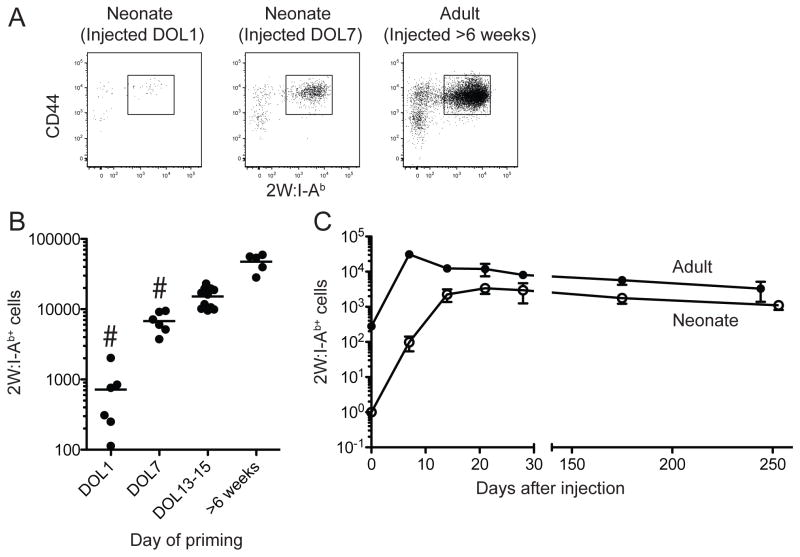

We next investigated the ability of 2W:I-Ab-specific CD4+ T cells in neonatal mice to proliferate and become effector cells. Neonatal and adult mice were injected i.p. with 2W peptide in CFA (22). Adult mice received 50 μg of 2W peptide, while one- or seven-day old mice were given 2 or 10 μg based on their smaller body weights. Seven days after injection of 2W peptide, spleens were harvested and enriched for 2W:I-Ab-specific cells as described above. An expanded population of CD44high 2W:I-Ab-specific CD4+ T cells was present in the spleens of mice of all ages (Fig. 3A). This result suggests that neonatal naïve CD4+ T cells are able to generate effector cells following exposure to the 2W peptide with an adjuvant.

Figure 3.

Expansion of 2W:I-Ab-specific cells following immunization. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots showing 2W:I-Ab and CD44 staining on 2W:I-Ab tetramer-enriched CD4+ T cells from spleens of one-day old, seven-day old, or adult mice 7 days after injection of 2W peptide in CFA. (B) Number of 2W:I-Ab+ CD4+ T cells 7 days after immunization at the indicated ages. The horizontal lines identify the mean value at each time point. The hashtag sign indicates a group containing values that were significantly (p < 0.01) more variable than the corresponding values from adult mice based on an F-test. (C) Number of 2W:I-Ab+ CD4+ T cells in the spleens of individual mice injected with 2W peptide in CFA as adults (filled circles) or on the first day of life (open circles).

Kinetics of expansion of neonatal 2W:I-Ab-specific CD4+ T cells

We next assessed that kinetics of effector cell generation by neonatal T cells. One-day old mice were of particular interest because of their immunological similarity to preterm neonatal humans, which have a high risk of infection. These mice, and adult controls, were injected i.p. with 2W peptide emulsified in CFA to stimulate effector cell formation. One-day old mice with body weights of ~1 gm received 2 μg of 2W peptide, while 25-gm adult mice received 50 μg. Spleens were then harvested at weekly intervals and enriched for 2W:I-Ab-specific CD4+ T cells. While the number of adult cells peaked at 7 days after injection as expected from previous work (16), the number of neonatal cells did not peak until 21 days after injection. In addition, there was more mouse-to-mouse variation in the number of 2W:I-Ab-specific effector cells generated on day 7 after priming of one-day or seven-day old mice than there was for comparable cells from mice primed at later ages (Fig. 3B). The magnitude of peak effector cell generation was comparable for neonatal and adult T cells given the differences in the numbers of naïve T cells at the time of immunization. Thus, the main defects in effector cell generation by neonatal CD4+ T cells in response to peptide plus CFA immunization were delayed kinetics and poor early generation in some individuals.

Neonatal mice can develop a long-term CD4+ memory T cell response

The kinetics experiment also allowed an assessment of whether effector cells generated in neonatal mice produce long-term memory T cells. The mice that were immunized as adults with 2W peptide in CFA contained about 30,000 2W:I-Ab-specific effector cells on day 7, the day of peak effector cell production in adults, and about 5,000 memory cells on day 244 (Fig. 3C). One-day old mice immunized with 2W peptide in CFA contained about 3,000 2W:I-Ab-specific effector cells on day 21, the time of peak effector cell production in neonates, and about 1,000 memory cells on day 253. Thus, about 15% of adult or 30% of neonatal effector cells survived to become memory cells, respectively. These data indicate that neonatal effector cells are as good or better than adult effector cells at generating memory cells.

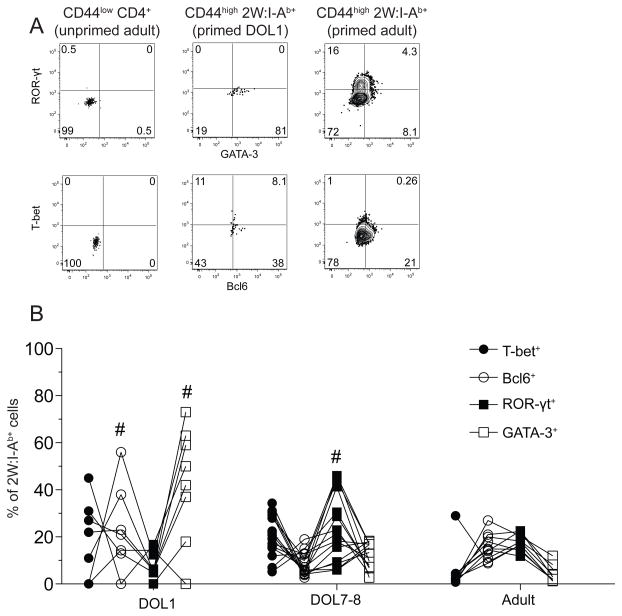

p:MHCII-specific CD4+ T cell differentiation is more variable in neonatal mice

We next assessed effector cell differentiation by intracellular detection of lineage-defining transcription factors: T-bet for Th1 cells, Bcl6 for follicular helper cells (Tfh), ROR-γt for Th17 cells, and GATA-3 for Th2 cells (23) (Fig. 4A). The 2W:I-Ab-specific effector T cell population in adult mice injected two weeks earlier with 2W peptide in CFA consisted on average of about 2% Th1 cells, 20% Tfh cells, 20% Th17 cells, and 5% Th2 cells (Fig. 4B). This general pattern was observed in 8 different adult mice. Priming of one-day old mice with 2W peptide in CFA generated a 2W:I-Ab-specific effector T cell population that differed in composition from that generated in adults and consisted on average of about 20% Th1 cells, 20% Tfh cells, 10% Th17 cells, and 30% Th2 cells. In addition, the frequencies of Tfh and Th2 cells were significantly more variable in one-day old mice than in adults. Priming of seven-day old mice generated effector cell populations that were more similar to adults and less variable than those generated in one-day old mice with the exception of Th17 cells. These results demonstrate that naïve p:MHCII-specific T cells in one-day old mice could generate all the effector cell types generated by adult cells but in a way that varied between individuals. The response became more consistent between individuals by day of life 7.

Figure 4.

Effector cell differentiation in response to immunization is more variable in neonatal mice than adult mice. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots of intracellular transcription factor staining in CD44low CD4+ T cells from unimmunized adult mice (left column), or CD44high 2W:I-Ab+ CD4+ T cells from day of life1 (middle column) or adult (right column) mice 7 days after i.p. injection of 2W peptide in CFA. (B) Frequency of 2W:I-Ab+ CD4+ T cells from one-day old (neonates), 7–8 day old mice, or adults expressing the indicated transcription factors 7 days after i.p. injection of 2W peptide in CFA. Lines connect values for the same mouse. Hashtag signs indicate neonatal values that were significantly (p < 0.05) more variable than the corresponding values from adult mice based on an F-test.

Discussion

We found that one-day old mice, the immunological equivalent of a premature human infant, on average already had the adult frequency of 10–20 naïve 2W:I-Ab-specific CD4+ T cells per million total CD4+ T cells (19). TdT-dependent TCR diversification is therefore not required to produce this particular epitope-specific population at its normal large size. This finding indicates that some epitope-specific naïve T cell populations are large because their ligands have chemical features that can be recognized by germ line-encoded TCRs.

Although one-day old mice had a normal frequency of 2W:I-Ab-specific CD4+ T cells in the thymus, the absolute number was low and none of these T cells were detected in the spleen at this time. This situation was likely related to the fact that thymic emigrants had just begun to populate the spleen. One-day old mice have only 105 CD4+ splenic T cells, only 1 of which on average would be expected to express a 2W:I-Ab-specific TCR. Thus, the T cell repertoires of the earliest neonatal mice could be small enough to lack certain p:MHCII-specific T cells for stochastic reasons. Such “holes in the repertoire” would be expected to be more common for other p:MHCII-specific naïve populations that are smaller than the 2W:I-Ab-specific population, which is one of the largest identified to date (16, 19).

Neonatal mice were surprisingly capable of producing 2W:I-Ab-specific effector cells given the few naïve cells that were present at the time of immunization. Even one-day old mice, which may have had no 2W:I-Ab-specific CD4+ T cells in the secondary lymphoid organs at the time of injection, were able to generate effector cells. This ability was likely due to rapid thymic output of CD4+ T cells shortly after immunization. Indeed, the number of 2W:I-Ab-specific naïve T cells in the spleen increased from ≤1 in one-day old mice to about 12 in 13-day old mice. Thus, many of the 2W:I-Ab-specific effector cells in the spleen at the peak 21 days after immunization on day 1 of life may have been generated from 2W:I-Ab-specific RTEs that entered the spleen after day 1. If the ~3,000 2W:I-Ab-specific effector cells in the spleen on day 21 were generated from 10 naïve cells, then each cell underwent a 300-fold clonal expansion, which matched or exceeded that of cells in adults. Thus, neonatal naïve CD4+ T cells showed no defect in clonal expansion when their low frequency at the time immunization was taken into account. The neonatal effector cells studied here were also efficient at generating memory cells on a per cell basis, which may explain the efficacy of certain vaccines that are given to neonates.

Naïve 2W:I-Ab-specific T cells in neonatal mice did take longer than the comparable cells in adult mice to generate the maximal number of effector cells. It is possible that this difference was due to the 2W peptide persisting longer in neonatal mice than in adult mice. Alternatively, it is possible that this difference related to the small size of the neonatal population. It was noted in a study of adults that small naïve populations take longer to generate the maximal number of effector cells than large populations (16), perhaps because inhibitory effects of competition between cells specific for the same p:MHCII ligand take longer when the initial starting population is small (24). Naïve 2W:I-Ab-specific T cell populations in neonates could therefore take longer than adult populations to generate the peak number of effector cells simply because they are smaller.

Individual variation in effector cell subset generation was another difference between neonatal and adult epitope-specific populations. A clue for the basis of this variability can be found in a study of effector cell differentiation in adults. It has been shown that single naïve T cells from an adult polyclonal repertoire specific for a single p:MHCII epitope vary greatly with respect to the type of effector cells they produce (17). When an epitope-specific naïve cell population consisted of many clones, unique clonal behaviors were found to average out such that the overall effector cell subset pattern for the entire population was similar in different mice. In contrast, when an epitope-specific naïve cell population consisted of a few clones, unique clonal behaviors did not average out and the overall effector cell subset pattern for the entire population differed in different mice. This phenomenon could account of the individual variability in effector cell differentiation observed for the small 2W:I-Ab-specific naïve cell populations in one-day old mice. It could also explain how on average neonatal 2W:I-Ab-specific naïve cells produced a higher percentage of Th2 cells than adult cells as observed in other studies (8, 25, 26), and yet some neonatal mice produced no Th2 cells and produced many Th1 cells.

Variability in effector cell generation could explain why neonates vary in their capacity to fight infection. Although human neonates have many more CD4+ T cells than mouse neonates it is still possible that they are susceptible to variable responses by small populations specific for a single epitope. Vaccine antigens are delivered to humans in small quantities at a single site on the body. These conditions are conducive to engagement of only a fraction of an epitope-specific population, especially in small lymph nodes of neonates, and favor T cell response variability. Our results therefore raise the possibility that some of the problems that neonates have with infections may to relate the inherent immune response variability that comes with small T cell repertoires.

Abbreviations used in this article

- B6

C57BL/6

- RTE

recent thymic emigrant

- p:MHCII

peptide:MHCII

- DOL

days of life

- CD4SP

CD4+ CD8−

- CD8SP

CD4− CD8+

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health: R01-AI39614 and R01-AI103760 (M.K.J.), T32-GM008244 and F30-DK093242 (R.W.N.), and the Pediatric Scientist Development Program, K12-HD000850 (M.N.R.).

References

- 1.Camacho-Gonzalez A, Spearman PW, Stoll BJ. Neonatal infectious diseases: evaluation of neonatal sepsis. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2013;60:367–389. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghazal P, Dickinson P, Smith CL. Early life response to infection. Curr Opin, Infect Dis. 2013;26:213–218. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32835fb8bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ygberg S, Nilsson A. The developing immune system - from foetus to toddler. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101:120–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson CB, Kollmann TR. Induction of antigen-specific immunity in human neonates and infants. Nestle Nutrition workshop series Paediatric programme. 2008;61:183–195. doi: 10.1159/000113493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fink PJ, Hendricks DW. Post-thymic maturation: young T cells assert their individuality. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:544–549. doi: 10.1038/nri3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haines CJ, Giffon TD, Lu LS, Lu X, Tessier-Lavigne M, Ross DT, Lewis DB. Human CD4+ T cell recent thymic emigrants are identified by protein tyrosine kinase 7 and have reduced immune function. J Exp Med. 2009;206:275–285. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webster RB, Rodriguez Y, Klimecki WT, Vercelli D. The human IL-13 locus in neonatal CD4+ T cells is refractory to the acquisition of a repressive chromatin architecture. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:700–709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609501200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rose S, Lichtenheld M, Foote MR, Adkins B. Murine neonatal CD4+ cells are poised for rapid Th2 effector-like function. J Immunol. 2007;178:2667–2678. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ridge JP, Fuchs EJ, Matzinger P. Neonatal tolerance revisited: turning on newborn T cells with dendritic cells. Science. 1996;271:1723–1726. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Opiela SJ, Koru-Sengul T, Adkins B. Murine neonatal recent thymic emigrants are phenotypically and functionally distinct from adult recent thymic emigrants. Blood. 2009;113:5635–5643. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-173658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forsthuber T, Yip HC, Lehmann PV. Induction of TH1 and TH2 immunity in neonatal mice. Science. 1996;271:1728–1730. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilfillan S, Benoist C, Mathis D. Mice lacking terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase: adult mice with a fetal antigen receptor repertoire. Immunol Rev. 1995;148:201–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1995.tb00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burt TD. Fetal regulatory T cells and peripheral immune tolerance in utero: implications for development and disease. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;69:346–358. doi: 10.1111/aji.12083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegrist CA. Neonatal and early life vaccinology. Vaccine. 2001;19:3331–3346. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moon JJ, Chu HH, Hataye J, Pagan AJ, Pepper M, McLachlan JB, Zell T, Jenkins MK. Tracking epitope-specific T cells. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:565–581. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moon JJ, Chu HH, Pepper M, McSorley SJ, Jameson SC, Kedl RM, Jenkins MK. Naive CD4(+) T cell frequency varies for different epitopes and predicts repertoire diversity and response magnitude. Immunity. 2007;27:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tubo NJ, Pagan AJ, Taylor JJ, Nelson RW, Linehan JL, Ertelt JM, Huseby ES, Way SS, Jenkins MK. Single naive CD4+ T cells from a diverse repertoire produce different effector cell types during infection. Cell. 2013;153:785–796. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rees W, Bender J, Teague TK, Kedl RM, Crawford F, Marrack P, Kappler J. An inverse relationship between T cell receptor affinity and antigen dose during CD4(+) T cell responses in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999:9781–9786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkins MK, Moon JJ. The role of naive T cell precursor frequency and recruitment in dictating immune response magnitude. J Immunol. 2012;188:4135–4140. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Starr TK, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Positive and negative selection of T cells. Annual review of immunology. 2003;21:139–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCaughtry TM, Wilken MS, Hogquist KA. Thymic emigration revisited. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2513–2520. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pape KA, Khoruts A, Mondino A, Jenkins MK. Inflammatory cytokines enhance the in vivo clonal expansion and differentiation of antigen-activated CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:591–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cannons JL, Lu KT, Schwartzberg PL. T follicular helper cell diversity and plasticity. Trends Immunol. 2013;34:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hataye J, Moon JJ, Khoruts A, Reilly C, Jenkins MK. Naive and memory CD4+ T cell survival controlled by clonal abundance. Science. 2006;312:114–116. doi: 10.1126/science.1124228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adkins B, Bu Y, Guevara P. Murine neonatal CD4+ lymph node cells are highly deficient in the development of antigen-specific Th1 function in adoptive adult hosts. J Immunol. 2002;169:4998–5004. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adkins B, Leclerc C, Marshall-Clarke S. Neonatal adaptive immunity comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:553–564. doi: 10.1038/nri1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]