Abstract

Introduction

Smokers in the criminal justice system represent some of the most disadvantaged smokers in the U.S., as they have high rates of smoking (70%–80%) and are primarily uninsured with low access to medical interventions. Few studies have examined smoking cessation interventions in racially diverse smokers and none have examined these characteristics among individuals supervised in the community. The purpose of this study is to determine if four sessions of standard behavioral counseling for smoking cessation would differentially aid smoking cessation for African American versus non-Hispanic white smokers under community corrections supervision.

Design

An RCT.

Setting/participants

Five hundred smokers under community corrections supervision were recruited between 2009 and 2013 via fliers posted at the community corrections offices.

Intervention

All participants received 12 weeks of bupropion plus brief physician advice to quit smoking. Half of the participants received four sessions of 20–30 minutes of smoking cessation counseling following tobacco treatment guidelines, while half received no additional counseling.

Main outcome measures

Generalized estimating equations were used to determine factors associated with smoking abstinence across time. Analyses were conducted in 2014.

Results

The end-of-treatment abstinence rate across groups was 9.4%, with no significant main effects indicating group differences. However, behavioral counseling had a differential effect on cessation: whites who received counseling had higher quit rates than whites who did not receive counseling. Conversely, African Americans who did not receive counseling had higher average cessation rates than African Americans who received counseling. Overall, medication-adherent African American smokers had higher abstinence rates relative to other smokers.

Conclusions

Racial disparities in smoking cessation are not evident among those who are adherent to medication. More research is needed to better understand the differential effect that behavioral counseling might have on treatment outcomes between white and African American smokers under community corrections supervision.

Introduction

Cigarette smoking remains the leading cause of death and disability in the U.S., killing one in two regular users.1 Although smoking prevalence has declined from a high of 45% in the 1960s to 17.8% in 2014 among the general population,1 it has remained high and unchanged (70%–80%) over this same time period among individuals in the criminal justice system.2,3 The U.S. places the largest percentage of its citizens under criminal justice supervision (one in 34 adults or 3% of all adults4) compared with other countries, and with very high rates of smoking, individuals in the U.S. criminal justice system now represent more than 12% of all current smokers countrywide.2,4

Despite the high prevalence of smoking and the resultant disease burden, few smoking cessation studies have been conducted with the U.S. criminal justice population. In one of the first such studies, a smoking cessation intervention (8–10 weeks of nicotine-replacement therapy [NRT] and ten sessions of group therapy) was provided to an incarcerated population of women. It demonstrated biochemically verified point prevalence quit rates for the intervention group of 18% at end of treatment and 12% at 12-month follow-up compared with 3% or less at any of the time points for the waitlist control group.3 Although these results established the feasibility of providing NRT for smoking cessation to those in the criminal justice system and demonstrated smoking cessation rates comparable to community samples even with the use of a strict carbon monoxide (CO) cutoff of <3 parts per million (ppm) for abstinence,3,5 it also revealed important racial differences. Specifically, non-Hispanic white women benefitted more from treatment relative to African American women, with approximately 5% higher cessation rates across time, showing that racial disparities are present even in a controlled environment.6

In light of recent smoking regulation policies implemented by the Federal Bureau of Prisons and state systems banning smoking in prison settings, attention has shifted to individuals under community corrections supervision (i.e., those who live in the community and continue to work and participate in society). These individuals represent a particularly vulnerable segment of the criminal justice population, as they not only have high rates of smoking (approximately 70%) but also have few smoking restrictions and limited opportunities to access traditional health care, including smoking cessation treatments.7 Although these individuals represent the greatest percentage of individuals in the criminal justice system (approximately 70%8), no smoking cessation interventions have been reported with this population, despite the fact that regular reporting requirements make this population accessible to interventions.

The following study represents the first smoking cessation clinical trial to be evaluated among smokers under community corrections supervision. Previous studies have noted that African Americans report positive expectancies and preferences for behavioral therapy over pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation intervention.2,9 However, whether these preferences are specific to subsets of the smoking population (e.g., those in community corrections or the chronically ill), and whether they result in actual differences in smoking cessation outcomes, has not been examined. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine if behavioral counseling would be differentially effective for smoking cessation among non-Hispanic white and African American smokers by comparing four sessions of 20–30 minutes of standard behavioral counseling (Counseling) to no counseling (No Counseling) provided in conjunction with bupropion and brief physician advice to quit (BPA). Bupropion is one of seven first-line pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation10 and was chosen over NRT or varenicline because of its antidepressant activity and availability in a generic formulation. As a large proportion of individuals under community corrections supervision suffer from depressed mood11 and are uninsured,12 a generic medication with antidepressant properties was selected. Although the Affordable Care Act may provide insurance to some individuals under community corrections supervision, the majority of individuals will likely remain uninsured owing to high rates of unemployment and frequent cycling between the community and incarceration.12

The primary hypothesis was that a significant race by treatment group interaction would be present, such that African American smokers would have higher quit rates for Counseling relative to No Counseling but would still have lower overall smoking cessation rates relative to white smokers. In addition, because previous studies have indicated that medication adherence is an important factor for abstinence,3 determining the role of medication adherence on treatment outcomes was investigated. It was hypothesized that African Americans would have lower medication adherence than whites and that these differences would account for lower rates of smoking abstinence among this group.

Methods

Participants

Six hundred eighty-nine participants were recruited via flyers posted at the community corrections office in Birmingham, Alabama and signed informed consent forms. Participants completed baseline assessment measures and had blood drawn to determine renal and liver function prior to receiving the study medication. Participants returned within 1 week to receive a physical exam and determine final study eligibility. Study criteria included:

smoking at least five cigarettes per day;

having a urinary cotinine level >200 mg/mL;

being aged ≥19 years;

being currently under criminal justice supervision (e.g., parole, drug court, probation; reporting requirements similar across groups);

not being incarcerated and not anticipating becoming incarcerated over the next year;

living in an environment that allowed smoking;

reporting the desire to quit smoking; and

being willing to take bupropion and receive four sessions of behavioral counseling to quit smoking.

Participants were excluded from the study if they:

had a history of bipolar disorder or a seizure disorder;

had a history of an eating disorder;

had current suicidal ideation or a suicide attempt in the past 6 months;

were pregnant or nursing a child;

were non-English speaking;

had cognitive impairment such that they were unable to provide informed consent; or

were medically unstable (e.g., severe renal impairment, elevation of liver enzymes three times the upper limit of normal).

All participants who were otherwise medically or psychiatrically stable were included in this study.

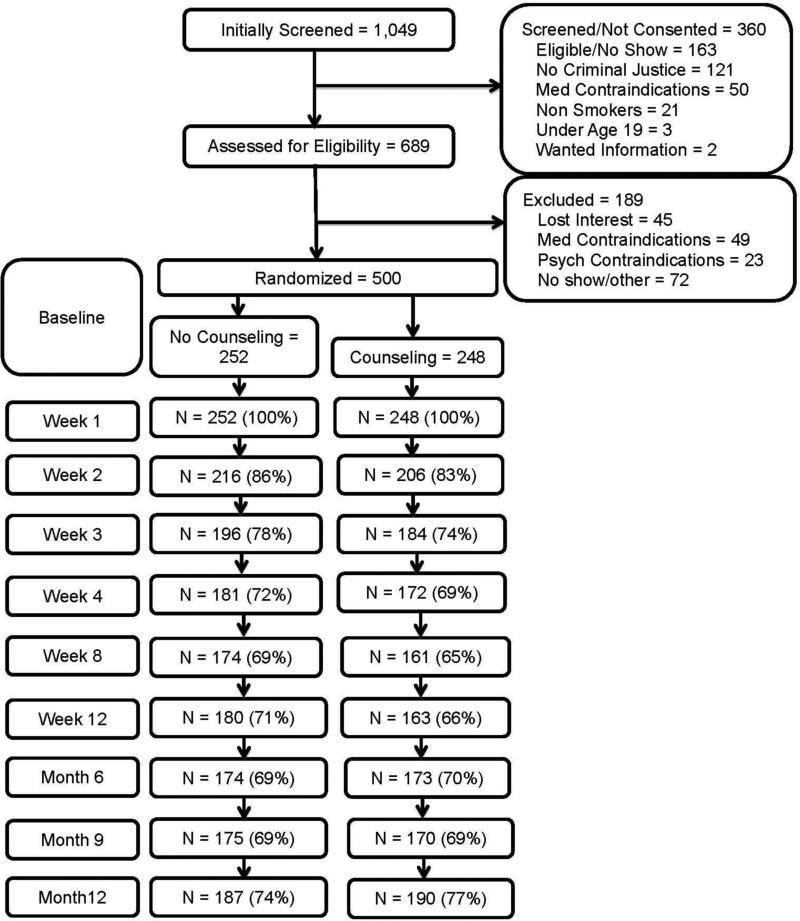

A total of 500 participants received 12 weeks of bupropion and BPA to quit. In addition, half of participants were randomized to receive more intensive counseling (Counseling), which included four sessions of 20–30 minutes of behavioral counseling for smoking cessation. Overall, retention in this study was about 76% at 1 year. A CONSORT flow diagram for the study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram.

Measures

Participants completed questionnaires that assessed demographic information, including race, age, gender, and education level. Participants also completed questionnaires that assessed smoking history, including average number of cigarettes smoked per day, age of smoking initiation and daily smoking, number of previous quit attempts and difficulty experienced in quitting, type of cigarette typically smoked (e.g., regular, menthol), use of other tobacco products, any personal or family medical problems associated with smoking, and whether they lived with a current smoker. Past history of making a cessation attempt was queried, specifically the types of cessation interventions that had been tried in the past (e.g., NRT or other medications, behavioral therapy) and whether a medical professional had ever discussed smoking cessation. Furthermore, participants received standard, validated smoking questionnaires, including the Fagerström Test of Cigarette Dependence (FTCD)13, the Questionnaire of Smoking Urges-Short Form (QSU-SF),14 and the Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (MNWS)15. Motivation to quit was assessed via the “Readiness Rulers,” which assessed interest, motivation, and self-efficacy to quit smoking on a 7-point Likert scale. In addition, participants were asked if they had intentions to quit, using the categories of within the next 30 days, within 6 months, or not considering quitting. Medication adherence was determined at each visit via self-reported missed doses. Participants were coded as adherent if they reported taking ≥80% of their scheduled doses since the time of their last appointment. An overall adherence measure was calculated for all time points if participants reported being medication adherent during ≥80% of their study visits. Finally, the primary outcome of interest was a CO ≤3 ppm at all study visits, which indicated abstinence. CO ≤3 ppm has been reported to be a better indicator of 24-hour smoking abstinence than higher values of CO.5,12,13 CO was measured using the Vitalograph BreathCO monitor.

Procedures

Participants were initially prescreened for inclusion and exclusion criteria and, if eligible, scheduled for a baseline assessment at the community corrections offices. During baseline assessment, participants provided informed consent, completed study assessments, provided urine for cotinine verification of smoking as well as pregnancy screening for women of childbearing potential, had blood drawn to assess for general health, and expired air to measure CO. Participants who were not literate had the questionnaires read aloud to them by study staff. Participants returned within 1 week and received a brief physical and a review of laboratory findings to determine final eligibility. All participants received a 12-week supply of bupropion, instructions on medication usage, and BPA. The study physician was a white female psychiatrist who provided advice (consistent with smoking cessation guidelines10) to set a quit day about 1–2 weeks after starting the medication and stressed the importance of medication adherence. In addition, half of the participants received weekly sessions of 20–30 minutes of counseling during the first 4 weeks of treatment provided by an upper-level graduate student or a postdoctoral clinical psychology fellow (93.6% of sessions provided by a white male therapist). The weekly counseling sessions focused on cognitive and behavioral strategies for smoking cessation, including psychoeducation about the addiction process, identification of triggers, goal setting, and strategies to cope with cravings (Counseling). To further bolster these sessions, participants in the Counseling group also received a 15-page client workbook based on the ACT Center for Tobacco Treatment, Education and Research (The University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi) that covered these same principles. Participants were asked to use their workbooks at home, and homework from these workbooks was reviewed at subsequent sessions. Counselors were doctoral- or master's-level clinical psychologists who had been trained in smoking cessation counseling through a week-long Tobacco Treatment Specialist training at the University of Mississippi Medical Center ACT Center. All counselors received weekly supervision by a licensed clinical psychologist who specialized in tobacco treatment. Participants in the No Counseling arm completed session assessments but did not receive any additional counseling.

The randomization scheme was blocked on race (white versus African American) to ensure equal representation of racial groups in each intervention arm. After the medical visit, participants returned for weekly visits through Week 4 and then returned at Weeks 8 and 12 (end of treatment). Long-term follow-up was at Months 6, 9, and 12. Participants were compensated $20 for the baseline visit, medical visit, and Week 8 and 12 visits, $10 for Week 1–4 visits, and $50 for Month 6, 9, and 12 visits, for a total of $270 for completing all visits over the 1-year period. Data were collected from 2009 until 2013 and analyses were completed in 2014. This study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01257490) and received approval by the University of Alabama at Birmingham IRB.

Statistical Analysis

The treatment groups were compared on baseline demographic and smoking characteristics using ANOVA or chi-square procedures for continuous or categorical variables, respectively. The primary outcome of interest was smoking abstinence at each time point as defined using CO ≤ 3 ppm, although we compared treatment outcomes using the traditional CO cut off of ≤10 ppm as well. We used generalized estimating equation (GEE) methods to examine the impact of the smoking-cessation intervention by treatment group and race across study time points. The model in this analysis included race (white versus African American) and type of treatment (Counseling versus No Counseling). Main effects of these variables as well as the interaction between race and treatment were tested. In addition, significant covariates were controlled in analyses, including treatment interest, abstinence self-efficacy, number of cigarettes smoked yesterday, and medication adherence (yes versus no). Similar to previous studies, participants were deemed to be medication adherent if they reported taking ≥80% of their doses of medication.18 Ten time points were collected in this study, including the baseline visit, Weeks 1–4, Weeks 8 and 12, and follow-up at Months 6, 9, and 12. Interactions between treatment group and race stratified by medication adherence were examined using chi-square analyses to determine if race or treatment group impacted medication adherence. Participants who dropped out of the intervention or otherwise did not attend their appointment were coded as smoking and non-adherent to their medications.

Results

The sample of participants was primarily African American (68%) men (67%) who had never been married (54.2%) and had a high school education or less (69%). Overall, about a quarter of the sample had a history of treatment for mental illness and about two thirds had been treated in the past for substance use. No differences were found between the two treatment groups on demographic characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics (N=500)

| Variable | Total (N=500) | No Counseling (n=252) | Counseling (n=248) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean | 37.4 | 38.1 | 36.7 | 0.15 |

| SD | 11.3 | 11.3 | 11.3 | ||

| Race | White | 32.0% | 31.3% | 32.7% | 0.75 |

| African American | 68.0% | 68.7% | 67.3% | ||

| Sex | Male | 67.0% | 64.7% | 69.4% | 0.27 |

| Female | 33.0% | 35.3% | 30.6% | ||

| Marital status | Never married | 54.2% | 53.6% | 54.9% | 0.85 |

| Married | 10.8% | 9.9% | 11.8% | ||

| Divorced/Separated | 31.5% | 32.9% | 30.1% | ||

| Widow | 3.4% | 3.6% | 3.3% | ||

| Education level | <HS | 31.7% | 34.1% | 29.1% | 0.42 |

| HS/GED | 37.3% | 34.9% | 39.7% | ||

| >HS | 31.1% | 31.0% | 31.2% | ||

| History of mental health treatment | 24.9% | 25.8% | 24.1% | 0.66 | |

| History of substance abuse treatment | 66.4% | 68.1% | 64.6% | 0.41 | |

GED, General Educational Development; HS, High School

The smoking characteristics of the two treatment groups are presented in Table 2. On average, participants smoked about 17.9 cigarettes per day, had a CO level of 17.3 ppm, primarily smoked menthol cigarettes (71.6%), and had an FTCD score of 5.2, indicating moderate dependence. Participants reported high levels of motivation to quit (5.9 of 7) and indicated relatively high levels of social support (5.8 of 7) for smoking cessation. Less than half reported that a health professional had ever advised them to quit smoking. Expectancies for smoking-cessation interventions varied: self-help materials demonstrated the lowest efficacy expectancy (3.9 out 7), and individual counseling and medications such as bupropion or varenicline had the highest expectancies associated with their use (4.9 and 5.2 of 7, respectively). Overall medication adherence was 44%, with significantly higher adherence among the No Counseling group relative to smokers who received Counseling. Participants randomized to No Counseling reported a higher interest in quitting but lower abstinence self-efficacy relative to participants randomized to Counseling. Individuals who receive Counseling reported smoking a greater number of cigarettes the day before their session. These variables were included as covariates in subsequent analyses.

Table 2.

Baseline Smoking Characteristics (N=500)

| Variable | Total (n=500) | No Counseling (n=252) | Counseling (n=248) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(SD) or % | M(SD) or % | M(SD) or % | ||

| Average CPD | 17.9(10.7) | 17.6(11.2) | 18.3(10.2) | 0.49 |

| Number smoked today | 5.9(5.6) | 5.5(5.3) | 6.4(6.0) | 0.08 |

| Number smoked yesterday | 14.8(9.5) | 13.5(8.2) | 16.2(10.6) | <0.01 |

| CO level (ppm) | 17.3(10.1) | 17.5(10.4) | 17.0(9.8) | 0.65 |

| Menthol use | 71.6% | 71.0% | 72.2% | 0.78 |

| FTCD | 5.2(2.1) | 5.4(1.9) | 5.2(2.1) | 0.36 |

| QSU | 38.8(16.1) | 39.5(16.9) | 38.1(15.3) | 0.33 |

| HHWS | 11.4(7.0) | 11.6(7.3) | 11.3(6.8) | 0.60 |

| CES-D | 15.1(10.2) | 15.4(10.1) | 14.8(10.3) | 0.55 |

| Interest in quitting | 6.1(1.2) | 6.3(1.1) | 6.0(1.3) | 0.04 |

| Abstinence self-efficacy | 5.5(1.6) | 5.3(1.7) | 5.7(1.5) | 0.01 |

| Motivation to quit | 5.9(1.4) | 5.9(1.4) | 5.8(1.5) | 0.24 |

| Social support for quitting | 5.8(1.8) | 5.8(1.7) | 5.8(1.8) | 0.90 |

| Health professional recommended quitting | 47.3% | 50.4% | 44.1% | 0.23 |

| Expectancies for interventions | ||||

| Medication | 5.2(1.7) | 5.3(1.7) | 5.1(1.7) | 0.48 |

| NRT | 4.3; 2.1 | 4.4; 2.2 | 4.1; 2.0 | 0.29 |

| Group therapy | 4.2; 2.1 | 4.2; 2.2 | 4.1; 2.0 | 0.56 |

| Individual therapy | 4.9; 1.9 | 4.9; 2.1 | 5.0; 1.9 | 0.57 |

| Self-help materials | 3.9; 2.1 | 4.0; 2.1 | 3.8; 2.1 | 0.43 |

| Medication adherence1 | 44.4% | 49.2% | 39.5% | 0.03 |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

CO, Carbon Monoxide; FTCD, Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence; QSU, Questionnaire of Smoking Urges; HHWS, Hughes-Hatsukami Withdrawal Scale; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression

Medication Adherence was measured across time in the study and was not a baseline characteristic.

A CO cut off of ≤3 ppm was used to indicate abstinence, as this cutoff was found to most closely correspond to cotinine level.5,17 No significant differences across time were found between the intervention groups. The end-of-treatment cessation rates using CO ≤3 ppm indicating abstinence were 9.3% for the Counseling group versus 9.5% for the No Counseling group (χ2=0.01, p=0.92). To compare to the extant literature, which generally uses a CO cutoff of ≤10 ppm,19 cessation rates tripled to 28.4% versus 9.4% quit at end of treatment for 10 ppm or 3 ppm, respectively (χ2=3.5, p=0.06). All subsequent analyses utilized the CO ≤3 ppm cutoff.

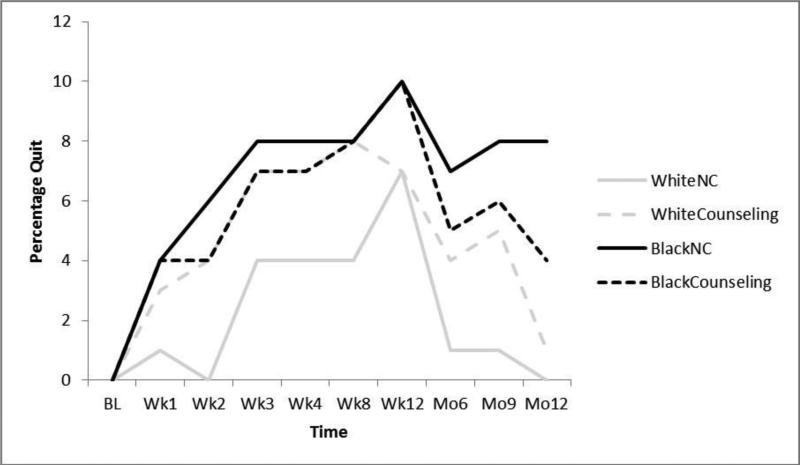

GEE analyses comparing the effect of treatment group on smoking abstinence by race and across time were performed. Significant covariates such as medication adherence, interest in quitting, abstinence self-efficacy, and number of cigarettes smoked yesterday were controlled in analyses. A significant interaction was observed between race and treatment across time, such that African Americans who were randomized to No Counseling had higher quit rates relative to African Americans who were randomized to Counseling. Conversely, white smokers who were randomized to Counseling had higher quit rates compared with whites who were randomized to No Counseling (Wald χ2=359.8, p<0.001, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Smoking cessation rates by race and treatment group across time.

The rate of medication adherence was 44.4%, with African Americans reporting higher medication adherence (47.6%) than whites (37.5%, χ2=4.5, p=0.03). In addition, individuals who were randomized to No Counseling had higher medication adherence relative to smokers who received Counseling (49.2% vs 39.5%, respectively, χ2=4.8, p=0.03). In examining the interaction between treatment and race on medication adherence, African Americans who received No Counseling had the highest adherence rates (52.6%), followed by African Americans who received Counseling (42.5%), whites who received No Counseling (41.8%), and whites who received Counseling (33.3%, Wald χ2=9.2, p=0.03).

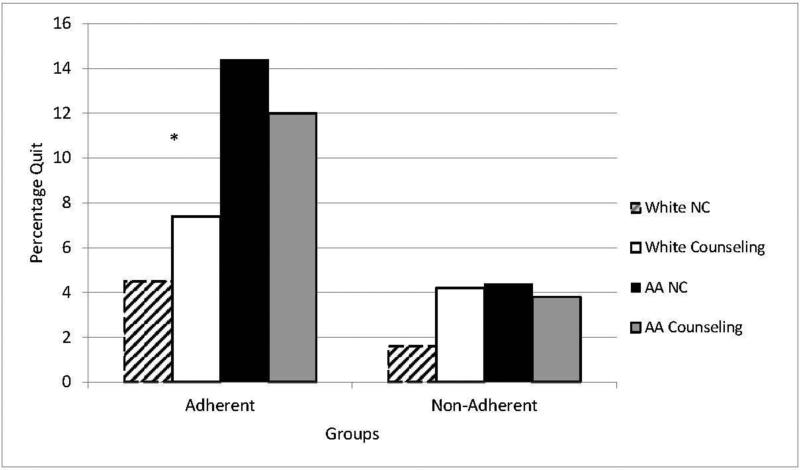

We were also interested in determining how the interactions among race, treatment group, and medication adherence may have impacted smoking cessation. A three-way interaction was found among treatment group, race, and medication adherence on cessation (Wald χ2=22.6, p<0.001, Figure 3). Among participants who reported being medication adherent, African American smokers who were randomized to No Counseling had quit rates across time of 14.4% relative to African American smokers who were randomized to Counseling (12%, χ2=2.3, p=0.13). Moreover, white smokers who were randomized to Counseling had similar quit rates to white smokers who were randomized to No Counseling (5.2% vs 4.5%, χ2=1.3, p=0.26). However, African Americans who were randomized to No Counseling had significantly higher quit rates than white smokers who were randomized to No Counseling (14.4% vs 4.5%, χ2=18.2, p<0.001), as well as white smokers who were randomized to Counseling (14.4% vs 7.4%, χ2=18.2, p<0.007). Among smokers who were non-adherent with medications, all smoking-cessation groups were low (quit rates <5%), with no significant differences between treatments by race group (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Smoking cessation rates by treatment group, race, and medication adherence. *p<0.001.

Discussion

This was the first study to examine smoking cessation treatment provided onsite to a community corrections sample. Despite a stated preference by African Americans for behavioral interventions,2,9 these results showed a moderating effect of race on treatment group such that African American smokers who were randomized to No Counseling had higher quit rates than African Americans randomized to Counseling. Conversely, non-Hispanic white participants were more likely to quit if they were randomized to Counseling. Although few studies have directly compared white and African American smokers in a clinical trial, this is the first time the interaction between race and treatment group has been reported. These findings went against our original hypotheses that African Americans who received counseling would do better than African Americans without counseling, and worse than non-Hispanic white smokers. It also stands in contrast to previous findings of higher smoking cessation rates among incarcerated white women,6 as well as previous studies that have generally noted increased quit rates among non-Hispanic white smokers relative to African Americans.20–22

One possible explanation for this finding is the role of medication adherence in this population. Medication adherence has been shown to be a critical factor in successful smoking cessation,18,23,24 and difficulties with adherence have been documented across various populations and in relation to chronic diseases.25–27 A similar pattern was found in this study, with medication adherence playing a critical role in successful cessation. However, a unique finding in this study was that behavioral counseling appeared to undermine medication adherence, regardless of racial group. This effect was particularly true for African Americans, who had significantly higher medication adherence and subsequent cessation when provided No Counseling compared with Counseling (52.6% vs 42.5%). Non-Hispanic whites demonstrated higher cessation with Counseling, despite demonstrating lower medication adherence with Counseling than with No Counseling. One possible explanation for this finding may be that individuals from disadvantaged populations with low health literacy, such as the sample in this study, may be less familiar with using pharmacotherapy aids and may be more comfortable with behavioral therapy. Thus, they may disregard pharmacotherapy when it is offered in conjunction with behavioral therapy, whereas when only BPA is offered, the message is almost exclusively focused on medication adherence and use of the medication. Partial support for this hypothesis is found in a recent study that noted higher cessation rates among African American veteran smokers relative to white smokers when both groups were provided with medication, regardless of the behavioral intervention (proactive care model versus usual care).28 An alternate hypothesis specific to this population may be that participants perceived therapy as authoritarian and did not want to follow the suggestions offered by the therapist. Unfortunately, data were not collected that would have explored these motivations, and more research is needed to understand the underlying dynamics of how therapy may have affected smoking cessation rates among African American smokers.

Limitations

There were a number of limitations to the current study that must be considered when interpreting its results. First, medication adherence was verified by self-report only. Queries with regard to medication adherence may carry demand characteristics and participants’ actual use of medication may have been overstated. Furthermore, socially desirable responding by African American smokers has been previously documented29–31; thus, reports of medication adherence may have been inflated among African American participants in particular. In addition, although sessions were not specifically audiotaped or coded, all counselors received specialized training in tobacco treatment and were required to engage in weekly supervision meetings to ensure behavioral protocol adherence. Also, the current study did not consider ethnoracial groups outside of African Americans and non-Hispanic whites. More diverse racial sampling would have allowed for a broader, more holistic comparison of racial groups, though it is noted that the current study's sample is reflective of regional demographics. Relatedly, the majority of the counseling was provided by white men whereas the majority of the participants were African American men. It is also unclear if our findings may be a unique characteristic of the community corrections population, specific to this sample, or just never investigated in the few clinical trials that recruited adequate numbers of African American and non-Hispanic white smokers. Individuals in the criminal justice system frequently present with very low SES and numerous medical and psychiatric comorbidities that complicate treatment32–34; whether the current results generalize to non–criminal justice populations is not known. Finally, because the current study was conducted in an area of the U.S. Deep South with a conspicuous past of racial segregation and maltreatment, the present findings may not generalize to geographic regions or sociocultural contexts with dissimilar histories of racial relations. Additional research is needed to determine if these findings can be replicated with other samples of smokers from other geographic regions in the country.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the current study represents a well-powered RCT that offers a number of important implications. First, despite reported preferences for behavioral interventions, African American smokers may achieve the most smoking cessation success with brief pharmacologic interventions only. Although this is speculative at this point, it could be that African American's preferences for behavioral interventions lead them to disregard use of pharmacotherapy when provided in conjunction with behavioral interventions. Second, efforts aimed at boosting medication adherence will likely increase the efficacy of existing smoking cessation interventions; regardless of race, rates of medication adherence were low overall (44%). Medication adherence in smoking cessation interventions has traditionally been quite low,35,36 particularly among low-income and ethnic minorities,37,38 and interventions focused on increasing adherence could be an important way to reduce smoking cessation disparities.39

Future research should aim to replicate and extend the current findings of the interactions among racial differences, behavioral therapy, and medication adherence in geographically diverse, non–criminal justice samples. Understanding factors that promote medication adherence among smokers and evaluating the efficacy of novel treatments designed to boost medication adherence are of particular interest and represent priorities for future investigation. Ultimately, maximizing medication adherence could markedly reduce smoking-related racial disparities,39 thereby achieving a critical public health goal.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Ms. Sonya Hardy and Mr. Nandan Katiyar for their assistance with data collection. This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute and NIH (R01CA141663) to KLC. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

KLC conceptualized the project. XZ, KLC, and CBC contributed to the data analysis. All of the authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript, including approval of the final version. Portions of this paper were presented at the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco Annual Meeting in Seattle, February 2014.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.CDC Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2005-2013. MMWR. 2014;63(47):1108–1112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cropsey KL, Jones-Whaley S, Jackson DO, Hale GJ. Smoking characteristics of community corrections clients. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(1):53–58. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntp172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cropsey KL, Eldridge GD, Weaver MF, Villalobos GC, Stitzer ML, Best AM. Smoking cessation intervention for female prisoners: addressing an urgent public health need. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(10):1894–1901. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.128207. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.128207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carson EA, Sabol WJ. Prisoners in 2011. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Dec, 2012. NCJ 239808. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cropsey KL, Eldridge GD, Weaver MF, Villalobos GC, Stitzer ML. Expired carbon monoxide levels in self-reported smokers and nonsmokers in prison. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(5):653–659. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789684. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14622200600789684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cropsey KL, Weaver MF, Eldridge GD, Villalobos GC, Best AM, Stitzer ML. Differential success rates in racial groups: results of a clinical trial of smoking cessation among female prisoners. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(6):690–697. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp051. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntp051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eldridge GD, Cropsey KL. Smoking bans and restrictions in U.S. prisons and jails: consequences for incarcerated women. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(2):179–180. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glaze LE, Parks E. Correctional Populations in the United States, 2011. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Nov, 2012. NCJ 239972. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cropsey KL, Leventhal AM, Stevens EN, et al. Expectancies for the effectiveness of different tobacco interventions account for racial and gender differences in motivation to quit and abstinence self-efficacy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(9):1174–1182. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu048. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntu048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline. U.S. Public Health Service; Rockville, MD: 2008. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 Update. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sirdifield C. The prevalence of mental health disorders amongst offenders on probation: a literature review. J Ment Health. 2012;21(5):485–498. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2012.664305. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2012.664305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rich JD, Chandler R, Williams BA, et al. How health care reform can transform the health of criminal justice-involved individuals. Health Aff. 2014;33(3):462–467. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1133. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fagerstom K. Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(1):75–78. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiffany ST. A critique of contemporary urge and craving research: Methodological, psychometric, and theoretical issues. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1992;14(3):123–139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0146-6402(92)90005-9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes JR, Hatsukami D. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43(3):289–294. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, Jao NC. Optimal carbon monoxide criteria to confirm 24-hr smoking abstinence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(5):978–982. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/nts205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cropsey KL, Trent LR, Stevens EN, Clark CB, Lahti AC, Hendricks PS. How low should you go? Determining the optimal cut-off for expired carbon monoxide using cotinine as reference. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(10):1348–1355. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu085. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntu085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Catz SL, Jack LM, McClure JB, et al. Adherence to varenicline in the COMPASS smoking cessation intervention trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(5):361–368. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benowitz NL, Jacob P, Ahijevych K, et al. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;4(2):149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okuyemi KS, Faseru B, Sanderson Cox L, Bronars CA, Ahluwalia JS. Relationship between menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation among African American light smokers. Addiction. 2007;102(12):1979–1986. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02010.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King G, Polednak A, Bendel RB, Vilsaint MC, Nahata SB. Disparities in smoking cessation between African Americans and Whites: 1990-2000. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(11):1965–1971. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.11.1965. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.11.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trinidad DR, Perez-Stable EJ, White MM, Emery SL, Messer K. A nationwide analysis of U.S. racial/ethnic disparities in smoking behaviors, smoking cessation, and cessation-related factors. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(4):699–706. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.191668. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.191668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hays JT, Leischow SJ, Lawrence D, Lee TC. Adherence to treatment for tobacco dependence: association with smoking abstinence and predictors of abstinence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(6):574–581. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq047. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntq047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raupach T, Bown J, Herec A, Brose L, West R. A systematic review of studies assessing the association between adherence to smoking cessation medication and treatment success. Addiction. 2014;109(1):35–43. doi: 10.1111/add.12319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/add.12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cutler DM, Everett W. Thinking outside the pillbox—mediation adherence as a priority for health care reform. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1553–1555. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1002305. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1002305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Jones CD, et al. Interventions to improve adherence to self-administered medications for chronic diseases in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):785–795. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-11-201212040-00538. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-157-11-201212040-00538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demonceau J, Ruppar T, Kristanto P, et al. Identification and assessment of adherence-enhancing interventions in studies assessing medication adherence through electronically compiled drug dosing histories: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Drugs. 2013;73(6):545–562. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0041-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40265-013-0041-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgess DJ, van Ryn M, Noorbaloochi S, et al. Smoking cessation among African American and white smokers in the Veterans Affairs health care system. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 4):S580–S587. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302023. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Link MW, Mokdad AH, Stackhouse HF, Flowers NT. Race, ethnicity, and linguistic isolation as determinants of participation in public health surveillance surveys. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A09. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Link MW, Mokdad AH. Alternative modes for health surveillance surveys: an experiment with web, mail, and telephone. Epidemiology. 2005;16(5):701–704. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000172138.67080.7f. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.ede.0000172138.67080.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher MA, Taylor GW, Shelton BJ, Debanne S. Age and race/ethnicity-gender predictors of denying smoking, United States. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(1):75–89. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2008.0000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2008.0000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cropsey KL, Binswanger IA, Clark CB, Taxman FS. The unmet medical needs of correctional populations in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc. 2012;104(11-12):487–492. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30214-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Binswanger IA, Redmond N, Steiner JF, Hicks LS. Health disparities and the criminal justice system: an agenda for further research and action. J Urban Health. 2012;89(1):98–107. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9614-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11524-011-9614-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steadman HJ, Osher FC, Robbins PC, Case B, Samuels S. Prevalence of serious mental illness among jail inmates. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(6):761–765. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.6.761. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/ps.2009.60.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.CDC Quitting Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2001–2010. MMWR. 2011;60(44):1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balmford J, Borland R, Hammond D, Cummings M. Adherence to and reasons for premature discontinuation from stop-smoking medications: data from the ITC four-country survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(2):94–102. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntq215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carpenter MJ, Ford ME, Cartmell K, Alberg AJ. Misperceptions of nicotine replacement therapy within racially and ethnically diverse smokers. J Natl Med Association. 2011;103(9-10):885–894. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30444-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan KK, Garrett-Mayer E, Alberg AJ, Cartmell KB. Carpenter MJ Predictors of cessation pharmacotherapy use among black and non-Hispanic white smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(8):646–652. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr051. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simeonova E. Doctors, patients, and the racial mortality gap. J Health Econ. 2013;32(5):895–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.07.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]