Abstract

Introduction

Although smoking prevalence has been declining for smokers without mental illness, it has been static for those with mental illness. The purpose of this study is to examine differences in smoking rates and trajectories of smoking prevalence in the often-overlooked population of smokers with poor mental health, compared with those with better mental health.

Methods

Data were obtained from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System from 2001 to 2010 to examine the relationship between poor mental health and current, daily, and intermittent tobacco use in New Jersey. Data were analyzed in 2014.

Results

During 2001–2010, current, daily, and intermittent smoking prevalence was higher in participants with poor mental health than those with better mental health. In addition, with the exception of 2 years, prevalence rates remained unchanged in this 10-year period for those with poor mental health while they significantly decreased for those with better mental health.

Conclusions

The disparity in which smokers with poor mental health are more likely to be current smokers and less likely to be never smokers as compared with those with better mental health has increased over time. These data suggest the need to more closely examine tobacco control and treatment policies in smokers with behavioral health issues. It is possible that tobacco control strategies are not reaching those with poor mental health, or, if they are, their messages are not translating into successful cessation.

Introduction

Tobacco use is the most common preventable cause of death in the U.S., with more than 443,000 adults dying from tobacco-related illnesses each year.1 Although there has been a decrease in smoking prevalence since 2005,2 18.1% of U.S. adults continue to smoke cigarettes.2 Prevalence rates are not evenly distributed throughout the population, however, and sharp disparities exist, suggesting that tobacco control efforts may not be reaching all smokers (e.g., those with mental illness, those living in poverty). National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data from 2009–2011 show that adults with mental illness are significantly more likely to be smokers as compared with those without mental illness (36.1% vs 21%). Among smokers, those with mental illness smoked more cigarettes per day than smokers without mental illness. In fact, 30.9% of all cigarettes smoked by adults in the U.S. are smoked by someone with a mental illness.3 In addition, data from the 2002 NSDUH indicate that adults with serious psychological distress have greater odds of tobacco use than those without serious psychological distress.4

Data are beginning to emerge indicating that although smoking prevalence has been dropping for smokers without mental illness, it has been static for those with mental illness.5–7 The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between mental health and smoking over time in New Jersey, and to add to this literature by looking specifically at daily smokers, intermittent smokers, and quit attempts.

Methods

Data Source

Data were obtained from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) for 2001–2010. Data were analyzed in 2014. BRFSS data are a random digit–dialed stratified probability sample. All 50 states independently conducted telephone surveys to collect data regarding chronic health issues in non-institutionalized, civilian U.S. adults aged ≥18 years. State samples were pooled by CDC to yield national estimates. The data set used in this paper was limited to residents of New Jersey. BRFSS data were weighted for the probability of selection of a telephone number, number of adults in a household, and number of telephones in a household. A final post-stratification adjustment was made for non-response and non-coverage of households without telephones.8 This methodology accounts for non-responses such as refusals and do not know responses in the analyses. There were no differences in missing data between those reporting better or poor mental health in our sample. Rates per 100,000 population were age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population, except where stratified by age group.9 Use of this data set did not require IRB review because research using de-identified data sets that are obtained from a commercial or governmental source, providing the investigator will never be given access to the identifier or the link is not considered human subject research, and is not governed by 45 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 46 or 21 CFR 50 & 56.

Measures

Respondents were asked the question: Do you now smoke cigarettes every day, some days, or not at all? Current cigarette smokers were defined as respondents who had smoked ≥100 cigarettes during their lifetime and responded every day or some days. Daily smokers were defined as those who had smoked ≥100 cigarettes during their lifetime and responded every day. Intermittent smokers were defined as those who had smoked ≥100 cigarettes during their lifetime and responded some days. Former smokers were those respondents who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and who, at the time of the survey, did not smoke at all. Never smokers were those respondents who reported never having smoked 100 cigarettes. Quit attempts were defined as an affirmative answer to the BRFSS item: During the past 12 months, have you quit smoking for 1 day or longer because you were trying to quit smoking? This question regarding quit attempts was only asked of current smokers. These definitions are consistent with those of CDC.10

Poor mental health was assessed with the BRFSS item: Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good? Participants who reported 14 or greater poor mental health days in the past 30 were defined as having poor mental health. This BRFSS item and cut off score has acceptable criterion validity and test–retest reliability.11–13 The mean number of poor mental health days in the past 30 days in New Jersey ranged from 2.9 to 3.4 between 2001 and 2010.

Statistical Analysis

SURVEY procedures in SAS, version 9.3,which accounts for the complex survey design of the BRFSS were used for statistical analyses. The PROC SURVEYFREQ procedure was applied to calculate all prevalence estimates with 95% CIs. The PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC procedure was used to estimate the differences in smoking prevalence by mental health status controlling for sociodemographic characteristics. All estimates were weighted to account for individual selection probabilities, non-response, and post-stratification.

Results

Sample

The total sample size ranged from 5,817 respondents in 2002 to 13,359 respondents in 2005. Demographic characteristics of the sample are displayed in Table 1. Although more than half (53.3%) of the sample reported that they were never cigarette smokers, 29.5% reported being former smokers, 12.1% were daily smokers, 4.7% were intermittent smokers, and 0.5% did not answer. Individuals reporting poor mental health were more likely to be current smokers and less likely to be never smokers than those reporting better mental health (χ2[3]=1653.60, p<0.0001). Almost a fifth (17.5%) of the sample reported >14 days of poor mental health in the last month.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N=80,126)

| Better mental health | Poor mental health | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Smoker status (%) | ||||

| Current, daily | 11.10 | 10.77 - 11.43 | 23.80 | 22.43 - 25.16 |

| Current, intermittent | 4.99 | 4.75 - 5.24 | 7.69 | 6.68 - 8.69 |

| Former smoker | 25.39 | 24.97 - 25.82 | 24.07 | 22.86 - 25.28 |

| Never smoker | 58.51 | 58.01 - 59.02 | 44.44 | 42.88 - 46.01 |

| Age (%) | ||||

| 18-24 | 10.41 | 9.95 - 10.87 | 12.25 | 10.90 - 13.59 |

| 25-34 | 17.13 | 16.70 - 17.54 | 17.38 | 16.00 - 18.76 |

| 35-44 | 21.50 | 21.08 - 21.91 | 22.25 | 20.96 - 23.53 |

| 45-54 | 18.97 | 18.59 - 19.35 | 22.47 | 21.26 - 23.69 |

| 55-64 | 13.74 | 13.42 - 14.05 | 13.77 | 12.88 - 14.66 |

| 65+ | 18.25 | 17.92 - 18.58 | 11.89 | 11.12 - 12.65 |

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Male | 49.01 | 48.49 - 49.53 | 40.08 | 38.47 - 41.69 |

| Female | 50.99 | 50.48 - 51.51 | 59.92 | 58.31 - 61.53 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White only/ non-Hispanic | 65.08 | 64.57 - 65.60 | 62.02 | 60.43 - 63.62 |

| Black only/ non-Hispanic | 11.09 | 10.75 - 11.43 | 12.94 | 11.94 - 13.94 |

| Hispanic | 14.83 | 14.42 - 15.24 | 18.82 | 17.36 - 20.29 |

| Other race | 8.99 | 8.65 - 9.34 | 6.22 | 5.44 - 6.99 |

| Education (%) | ||||

| Did not graduate high school | 8.52 | 8.21 - 8.83 | 13.87 | 12.56 - 15.18 |

| Graduated high school | 27.06 | 26.60 - 27.53 | 32.84 | 31.36 - 34.32 |

| Some college | 23.38 | 22.93 - 23.83 | 27.21 | 25.86 - 28.55 |

| College graduate | 41.04 | 40.54 - 41.54 | 26.09 | 24.81 - 27.36 |

| Income (%) | ||||

| < $10,000 | 2.75 | 2.57 - 2.94 | 7.60 | 6.51 - 8.69 |

| < $15,000 | 3.71 | 3.47 - 3.95 | 6.27 | 5.54 - 6.99 |

| < $20,000 | 5.86 | 5.59 - 6.14 | 10.06 | 8.98 - 11.14 |

| < $25,000 | 7.63 | 7.32 - 7.95 | 11.54 | 10.43 - 12.65 |

| < $35,000 | 9.54 | 9.23 - 9.85 | 10.59 | 9.62 - 11.55 |

| < $50,000 | 13.32 | 12.94 - 13.71 | 14.10 | 12.91 - 15.30 |

| < $75,000 | 16.46 | 16.04 - 16.88 | 14.36 | 13.23 - 15.49 |

| $75,000 or more | 40.71 | 40.17 - 41.25 | 25.49 | 24.06 - 26.92 |

Current Smoking Prevalence

The overall logit model (N=86,061) examining current (i.e., daily and intermittent) smoking prevalence in those with poor and better mental health between 2001 and 2010 was statistically significant (Wald F[25]=1847.04, p<0.0001). In addition, participant characteristics such as participant age, sex, race, income, and education were significant predictors of current smoking status in the model (all p<0.0001). The logit model (Table 2) revealed significantly greater prevalence of smoking among those reporting poor versus better mental health after adjusting for age, sex, race, income, and education (OR=2.001, 95% CI=1.836, 2.181, p<0.0001).

Table 2.

Logit Model Estimating Association Between Poor Mental Health and Current Smoker vs. Non-Smoker Status

| Log Odds (95% CI) |

p- value |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mental health status | ||

| Better | 1.0 [Reference] | |

| Poor | 2.001 (1.836 – 2.181) | <0.0001 |

| Year | ||

| 2001 | 1.0 [Reference] | |

| 2002 | 0.826 (0.687 – 0.993) | 0.0422 |

| 2003 | 0.912 (0.813 – 1.022) | 0.1119 |

| 2004 | 0.883 (0.787 – 0.991) | 0.0338 |

| 2005 | 0.868 (0.772 – 0.976) | 0.0180 |

| 2006 | 0.901 (0.798 – 1.017) | 0.0917 |

| 2007 | 0.888 (0.771 – 1.023) | 0.0997 |

| 2008 | 0.684 (0.600 – 0.779) | <0.0001 |

| 2009 | 0.790 (0.693 – 0.900) | 0.0004 |

| 2010 | 0.660 (0.581 – 0.751) | <0.0001 |

| Age | 0.977 (0.976 – 0.979) | <0.0001 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.0 [Reference] | |

| Female | 0.769 (0.726 – 0.816) | <0.0001 |

| Race | ||

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 1.0 [Reference] | |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 1.338 (1.214 – 1.474) | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic | 0.622 (0.548 – 0.706) | <0.0001 |

| Other race | 0.798 (0.675 – 0.944) | 0.0084 |

| Income | ||

| >$75,000 | 1.0 [Reference] | |

| $50,000 to less than $75,000 | 1.395 (1.274 – 1.528) | <0.0001 |

| $35,000 to less than $50,000 | 1.490 (1.353 – 1.641) | <0.0001 |

| $25,000 to less than $35,000 | 1.465 (1.320 – 1.625) | <0.0001 |

| $20,000 to less than $25,000 | 1.619 (1.435 – 1.827) | <0.0001 |

| $15,000 to less than $20,000 | 1.611 (1.412 – 1.838) | <0.0001 |

| $10,000 to less than $15,000 | 1.537 (1.301 – 1.817) | <0.0001 |

| Less than $10,000 | 1.681 (1.408 – 2.006) | <0.0001 |

| Education | ||

| College graduate | 1.0 [Reference] | |

| Some college | 1.923 (1.777 – 2.081) | <0.0001 |

| Graduated high school | 2.532 (2.336 – 2.745) | <0.0001 |

| Did not graduate high school | 2.910 (2.572 – 3.294) | <0.0001 |

Note: Logit Model (N=86,061) adjusts for age, sex, race, income, and education. Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

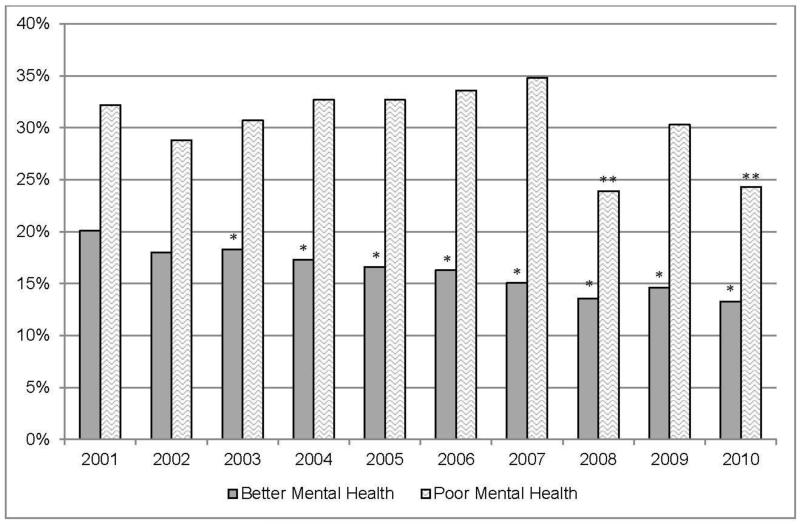

Figure 1 and Table 3 display smoking prevalence by year for those reporting poor versus better mental health. As compared to the 2001 reference year, current smoking prevalence rates were significantly reduced for those with better mental health during the 2001–2010 time period for each year except 2002. By contrast, reductions only occurred in 2008 and 2010 for those reporting poor mental health.

Figure 1.

Current smoking prevalence is higher in those reporting poor mental health 2001–2010

Note: Greater smoking prevalence was found in those with poor mental health as compared to those with better mental health, after adjusting for age, sex, race, income, and education (OR=2.001 [95% CI: 1.836–2.181], p<0.0001). Asterisks above the bar representing a given year and mental health status indicates that when adjusting for mental health, age, sex, race, income, and education, smoking prevalence is significantly lower in that year as compared to the reference year 2001 for those with either better (*) or poor (**) mental health.

Table 3.

Smoking Prevalence for Current Smokers With Better or Poor Mental Health Compared to 2001

| Better mental health | Poor mental health | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Year | N | % | OR | 95% CI | N | % | OR | 95% CI |

| 2001 | 5,206 | 20.1 | 1.00 | 1.00 – 1.00 | 674 | 32.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 – 1.00 |

| 2002 | 5,343 | 18.0 | 0.87 | 0.73 – 1.04 | 474 | 28.8 | 0.91 | 0.57 – 1.45 |

| 2003 | 9,958 | 18.3 | 0.89 | 0.79 – 0.99 | 1,151 | 30.7 | 0.93 | 0.71 – 1.22 |

| 2004 | 10,596 | 17.3 | 0.84 | 0.75 – 0.93 | 1,178 | 32.7 | 1.05 | 0.80 – 1.37 |

| 2005 | 12,123 | 16.6 | 0.79 | 0.71 – 0.89 | 1,236 | 32.7 | 1.05 | 0.78 – 1.40 |

| 2006 | 11,849 | 16.3 | 0.78 | 0.69 – 0.88 | 1,295 | 33.6 | 1.07 | 0.80 – 1.44 |

| 2007 | 6,344 | 15.1 | 0.73 | 0.63 – 0.84 | 752 | 34.8 | 1.19 | 0.84 – 1.69 |

| 2008 | 10,353 | 13.6 | 0.64 | 0.56 – 0.72 | 1,122 | 23.9 | 0.68 | 0.49 – 0.93 |

| 2009 | 10,710 | 14.6 | 0.68 | 0.60 – 0.77 | 1,250 | 30.3 | 0.93 | 0.68 – 1.26 |

| 2010 | 10,642 | 13.3 | 0.62 | 0.54 – 0.70 | 1,305 | 24.3 | 0.73 | 0.54 – 0.99 |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05) difference between current year and reference year 2001 within each mental health category.

Daily Smoking Prevalence

Like the model for current smoking, the overall logit model (N=81,887) specifically examining daily smoking prevalence in those with poor and better mental health between 2001 and 2010 was statistically significant (Wald F[25]=1793.74, p<0.0001). In addition, participant characteristics such as participant age, sex, race, income, and education were significant predictors of daily smoking status in the model (all p<0.0001). The logit model revealed significantly greater prevalence of daily smoking among those reporting poor versus better mental health (23.8% vs 11.1%) after adjusting for age, sex, race, income, and education (OR=2.163, 95% CI=1.967, 2.378, p<0.0001).

Intermittent Smoking Prevalence

Like the model for current and daily smoking, the overall logit model (N=75,116) specifically examining intermittent smoking prevalence in those with poor and better mental health between 2001 and 2010 was statistically significant (Wald F[25]=545.21, p<0.0001). In addition, participant characteristics such as participant age (p<0.0001), sex (p<0.001), race (p=0.007), income (p<0.001), and education (p<0.001) were significant predictors of intermittent smoking status in the model. The logit model revealed significantly greater prevalence of intermittent smoking among those reporting poor versus better mental health (7.69% vs 4.99%) after adjusting for age, sex, race, income, and education (OR=1.642, 95% CI=1.401, 1.924, p<0.0001).

Attempts to Quit Smoking

As shown in Table 4, no differences were found in attempts to quit smoking based on mental health status. Intermittent smokers, however, were significantly more likely to make a quit attempt than daily smokers among people with better mental health. Differences in quit attempts between daily and intermittent smokers were not statistically significant among people with poor mental health except for in 2004–2006.

Table 4.

Quit Attempts by Daily or Intermittent Smokers With Better or With Poor Mental Health

| Better mental health | Poor mental health | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Daily smoker | Intermittent smoker | Daily smoker | Intermittent smoker | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Year | N | % | 95% CI | N | % | 95% CI | N | % | 95% CI | N | % | 95% CI |

| 2001 | 750 | 51.6 | 46.8 - 56.4 | 295 | 73.4 | 67.1 - 79.6 | 173 | 55.3 | 44.8 - 65.8 | 53 | 75.4 | 57.6 - 93.2 |

| 2002 | 641 | 53.5 | 45.6 - 61.5 | 241 | 72.7 | 60.6 - 84.8 | 114 | 55.7 | 37.9 - 73.5 | 27 | 81.9 | 60.3 - 100.0 |

| 2003 | 1,260 | 49.5 | 46.2 - 52.9 | 487 | 67.4 | 62.3 - 72.5 | 274 | 57.9 | 50.5 - 65.4 | 71 | 66.6 | 53.1 - 80.0 |

| 2004 | 1,224 | 49.3 | 45.8 - 52.8 | 518 | 74.5 | 69.5 - 79.4 | 288 | 50.8 | 43.6 - 58.1 | 96 | 89.2 | 82.5 - 96.0 |

| 2005 | 1,412 | 51.4 | 47.7 - 55.1 | 528 | 76.5 | 70.6 - 82.3 | 300 | 51.3 | 41.3 - 61.4 | 93 | 76.6 | 62.0 - 91.3 |

| 2006 | 1,237 | 51.3 | 47.3 - 55.3 | 500 | 75.4 | 69.7 - 81.2 | 294 | 60.6 | 52.0 - 69.2 | 100 | 80.8 | 70.0 - 91.6 |

| 2007 | 698 | 55.7 | 50.2 - 61.2 | 254 | 75.5 | 67.7 - 83.3 | 177 | 68.1 | 59.7 - 76.6 | 57 | 86.0 | 71.2 - 100.0 |

| 2008 | 988 | 53.1 | 48.0 - 58.1 | 388 | 69.8 | 62.1 - 77.5 | 209 | 58.5 | 48.4 - 68.6 | 60 | 76.0 | 62.9 - 89.1 |

| 2009 | 980 | 52.4 | 47.7 - 57.1 | 465 | 72.6 | 64.4 - 80.8 | 262 | 64.7 | 55.0 - 74.4 | 99 | 62.7 | 45.8 - 79.6 |

| 2010 | 1,052 | 50.3 | 45.8 - 54.9 | 363 | 75.1 | 68.0 - 82.3 | 230 | 54.3 | 45.0 - 63.6 | 95 | 79.2 | 61.1 - 97.2 |

Note: Quit attempts = Stopped smoking for at least one day in the past year.

Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05) between daily and intermittent smokers within each mental health group at 95% CI. A significantly higher proportion of intermittent smokers make quit attempts as compared to daily smokers regardless of mental health status.

Discussion

This study examines smoking prevalence in New Jersey residents over the course of 10 years. These data indicate that the smoking prevalence of those with poor mental health was greater than those with better mental health. Perhaps more importantly, with the exception of 2 years, prevalence rates remained unchanged over 10 years for those with poor mental health while they significantly decreased for those with better mental health.

With few exceptions (i.e., 2008 and 2010), there were no decreases in smoking prevalence as compared to 2001 for smokers reporting poor mental health. Even within those two exceptions, the data require careful examination. The year 2008 appears to be an anomaly, as it represented a temporary, steep decline in smoking prevalence only for those with poor mental health (34.8% in 2007 to 23.9% in 2008), followed by a return to prevalence similar to the preceding year (30.3% in 2009). For this decline to signify a true decrease in smoking prevalence, rather than an anomaly, it would represent a steep, sustainable decrease beginning in 2008 and lasting at least until 2010 with no known external event precipitating such a sustained decline. In addition, this steep decline was not found in previous reports.7 Although the sampling methodology changed for the BRFSS after 2010 (with the inclusion of cell phone numbers starting in 2011), an examination of smoking prevalence in these groups beyond 2010 may assist in clarifying this issue.

The data for the year 2010 represent a barely significant decrease when compared to the 2001 reference year, with CIs ranging from 0.54 to 0.99 and nearly including 1.0 (Table 3). By contrast, analyses indicate significant decreases in smoking prevalence during the 2001–2010 time period for each year except 2002 for those reporting better mental health. This is consistent with previous reports5,7 which detected a significant decline in smoking prevalence among those reporting better mental health without a corresponding decline among smokers with poor mental health over the same time period. These findings are robust and compelling because all three data sets (i.e., ours, New York State,5 and Cook et al.7) used slightly different definitions of poor mental health.

This study represents the first to parse out daily and intermittent smokers with and without poor mental health. As intermittent smoking continues to grow while daily smoking declines in the general population,14 it will be important to examine these groups among those with mental health problems as well. The same pattern of results emerges when examining only daily smokers and only intermittent smokers as when examining all current (daily and intermittent) smokers. This pattern indicates that individuals with poor mental health are more likely to be daily smokers, intermittent smokers, and current (daily or intermittent) smokers than those with better mental health. Intermittent smokers are significantly more likely to make a quit attempt than daily smokers. In addition, intermittent smokers are significantly more likely to make a quit attempt than daily smokers among people with better mental health. Differences in quit attempts between daily and intermittent smokers were not statistically significant among people with poor mental health except for the years 2004–2006. A lack of statistical power associated with the small sample sizes for the daily and intermittent smoker categories among those with poor mental health may have hindered our ability to find statistically significant differences, however.

These data are also consistent with recent reports indicating that smokers with mental illness are less likely to successfully quit than smokers without mental illness.3 It is important to note, however, that these declines in smoking prevalence for those with better mental health, but not with poor mental health, are not due to differences in attempts to quit. Our data indicate that those with poor mental health attempt to quit smoking at similar rates as those with better mental health. In fact, our data indicate that smokers with poor mental health are consistently (though non-significantly) more likely to make quit attempts than those reporting better mental health (Table 4). Although these data do not provide direct evidence for the hardening hypothesis,15,16 which suggests that after a substantial decrease in smoking prevalence the remaining smokers in the population are now the hardest to treat, this is a possible explanation. There is evidence that smokers with mental illness are less likely to successfully quit over their lifetime and that this trend persists in even milder syndromes.4,17,18

Although these data clearly indicate that smokers with poor mental health have not enjoyed the decrease in smoking prevalence that those with better mental health have, the reasons remain unclear. It may be that when state tobacco control efforts are not targeted at disparity groups, these groups do not make substantial progress. Indeed, the New York data5 should be interpreted in the context of a moderately well funded statewide initiative. This suggests that even with moderately sufficient tobacco control funding, this group of smokers is not being reached by current population-based tobacco control strategies. As people with mental illness represent about one third, or 16 million people of an estimated total 51 million adult smokers in the U.S.,19 alternative tobacco control strategies—including treatments—must be developed and studied. A related possibility is that those who treat mental health populations do not routinely address tobacco use. Among physicians in New Jersey, psychiatrists demonstrate relatively low familiarity with available tobacco treatment services20 compared with other medical specialties. Additionally, tobacco dependence treatment services are often unavailable in behavioral health programs21 and clinicians overestimate the amount of treatment they provide.22

Limitations

An important limitation of this study was that because the BRFSS excluded institutionalized individuals (e.g., those in psychiatric hospitals, residential programs, and prisons), these data were likely underestimating the prevalence of smoking among those with poor mental health and underestimating the discrepancy in smoking reductions between the two groups. An additional limitation included the fact that the BRFSS definition of “poor mental health” is non-specific and was likely to contain a variety of problems and DSM-V diagnoses. These data also did not allow us to track important clinical variables such as number of quit attempts, quit attempts lasting less than 24 hours, number of cigarettes smoked per day, or cigarette dependence. The operationalization of a “quit attempt” as quitting for 1 day or longer may be particularly problematic in a population of smokers with poor mental health. It is unclear if the pattern of results would have been different if these data were able to capture quit attempts lasting less than a full day. It is also unclear if the pattern of results would have been different if these data were able to ensure that all quit attempts were purposeful attempts to quit smoking (rather than not smoking for a full day because they could not afford cigarettes that day or because they became institutionalized and were not permitted to smoke for at least a day). The former option leaves open the possibility that smokers with poor mental health could have reported even more quit attempts, whereas the latter opens the possibility for fewer reported quit attempts.

Finally, these data did not include people who use cell phones exclusively because the BRFSS did not start including cell phones in its random digit–dialing protocol until 2011. This may represent a limitation in the current study because young adult smokers may have been more likely to be unreachable through a landline-only protocol,23 although this limitation may have been offset by our use of age-adjusted smoking prevalence estimates. Data beyond 2010 were excluded because of the differences in sampling methodology (i.e., including cell phones after 2010).

Conclusions

This study adds to the current literature because it is the first to parse out daily and intermittent smokers with poor or better mental health. Additionally, these data suggest several policy implications. To address the disparity in which tobacco control progress is slower for those with poor mental health than those with better mental health, states need to provide greater tobacco control or clinical funding for smokers with poor mental health, behavioral healthcare providers need better training in tobacco dependence treatment, and behavioral healthcare systems need to integrate tobacco dependence treatment into their caseloads. Although smokers with behavioral health comorbidity should be designated as a tobacco use disparity group and receive priority funding, this is still not the case.21 We hope this paper calls attention to the unmet needs of this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1R34DA030652) and New Jersey Department of Health, Division of Family Health Services (DFHS14CTC007), awarded to the first author (MLS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.U.S. DHHS . How tobacco smoke causes disease: the biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease: A report of the surgeon general. CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2010. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2010/index.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agaku IT, King BA, Dube SR. Current cigarette smoking among adults – United States, 2005–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014 Jan 14;63(02):29–34. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6302a2.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gfroerer J, Dube SR, King BA, Garrett BE, Babb S, McAfee T. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years with mental illness – United States, 2009–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013 Feb 8;62(05):81–87. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6205a2.htm?s_cid=mm6205a2_w. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagman BT, Delnevo CD, Hrywna M, Williams JM. Tobacco use among those with serious psychological distress: results from the national survey of drug use and health, 2002. Addict Behav. 2008;33(4):582–592. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.11.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.New York State Department of Health Adults in New York who report poor mental health are twice as likely to smoke cigarettes. Tobacco Control Program StatShot. 2012 Feb;5(2) www.health.ny.gov/prevention/tobacco_control/reports/statshots/volume5/n2_mental_health_and_smoking_prevalence.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) . Smoking rate among adults with serious psychological distress remains high. The CBHSQ Report Data Spotlight. 2013 Jul 18; http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/spot120-smokingspd_/spot120-smokingSPD.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook BL, Wayne GF, Kafali EN, Liu Z, Shu C, Flores M. Trends in smoking among adults with mental illness and association between mental health treatment and smoking cessation. JAMA. 2014;311(2):172–182. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284985. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.284985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. DHHS . Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System operational and user’s guide (Version 3.0) CDC; Atlanta, GA: 2006. ftp.cdc.gov/pub/data/brfss/userguide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Age adjustment using the 2000 projected U.S. population. Healthy People Statistical Notes. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2001. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/statnt/statnt20.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CDC State-specific secondhand smoke exposure and current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1232–1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andresen EM, Catlin TK, Wyrwich KW, Jackson-Thompson J. Retest reliability of surveillance questions on health-related quality of life. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(5):339–343. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.5.339. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.5.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapp JM, Jackson-Thompson J, Petroski GF, Schootman M. Reliability of health-related quality-of-life indicators in cancer survivors from a population-based sample, 2005, BRFSS. Public Health. 2009;123(4):321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.10.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Kobau R. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s healthy days measures – population tracking of perceived physical and mental health over time. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:37. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiffman S. Light and intermittent smokers: background and perspective. Nicotine & Tob Res. 2009;11(2):122–125. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntn020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fagerström K, Furberg H. Will the smokers of the future be harder to deal with? Addiction. 2008;103(9):1576–1577. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02349.x. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes JR. The hardening hypothesis: is the ability to quit decreasing due to increasing nicotine dependence? A review and commentary. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117(2-3):111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.02.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal A, Sartor C, Pergadia ML, Huizink AC, Lynskey MT. Correlates of smoking cessation in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. Addict Behav. 2008;33(9):1223–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.04.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pratt LA, Brody DJ. Depression and smoking in the U.S. household population aged 20 and over, 2005-2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2010;34:1–8. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db34.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence D, Mitrou F, Zubrick SR. Smoking and mental illness: results from population surveys in Australia and the United States. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:285. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-285. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinberg MB, Alvarez MS, Delnevo CD, Kaufman I, Cantor JC. Disparity of physicians’ utilization of tobacco treatment services. Am J Health Behav. 2006;30(4):375–386. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2006.30.4.375. http://dx.doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.30.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams JM, Steinberg ML, Griffiths KG, Cooperman N. Smokers with behavioral health comorbidity should be designated a tobacco use disparity group. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(9):1549–1555. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301232. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams JM, Miskimen T, Minsky S, et al. Increasing tobacco dependence treatment through continuing education training for behavioral health professionals. Psych Services in Advance. 2014 Sep 15; doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300523. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delnevo CD, Gundersen D, Hagman BT. Declining estimated prevalence of alcohol drinking and smoking among young adults nationally: artifacts of sample undercoverage? Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008;167(1):15–19. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm313. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwm313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]