Abstract

Background

Ideal cardiovascular (CV) health by simultaneous presence of 7 ideal health metrics (blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, smoking, BMI, physical activity and diet) has been defined by the American Heart Association. In the current study we investigated the association of a CV health score (range 0–14), on the extent and progression of carotid atherosclerosis, assessed as carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) and total plaque area (TPA) by ultrasound at 5 years interval.

Methods and Results

A total of 219 participants (age 75.6±5.1) from the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility (AGES)-Reykjavik study were studied. Men with poor (low) CV health score had greater TPA than those with more optimal (high) score (61.5 (SD: 32.3), 44.4 (24.2) and 37.7 (23.2) mm2 for those with CV health score ≤ 6, 7–9 and ≥ 10 respectively, p<0.05). In linear analysis for men, log TPA was 0.088 mm2 (SE: 0.040 p<0.05) smaller for each additional point in the CV health score. CV health score was not associated with TPA in women, or cIMT in either sex. TPA increased in both sexes between visits. However, CV health score did not predict carotid atherosclerosis progression.

Conclusions

CV health score is associated with TPA in older men but not in women. Men with poor CV health score at the baseline visit had more extensive carotid atherosclerosis than those with better CV health score, although it did not predict the progression of carotid atherosclerosis.

Keywords: carotid arteries, imaging, cardiovascular health score

Introduction

Non-invasive imaging has been suggested as a method for estimating subclinical atherosclerosis to improve cardiovascular risk assessment1. B-mode ultrasound is an imaging method that has been widely used to detect and measure carotid intimamedia thickness (cIMT) and carotid plaques, which are arterial markers independently associated with cardiovascular risk factors2, 3 and cardiovascular disease4. Previous studies suggest that including measures of carotid atherosclerosis can improve coronary heart disease risk prediction.5–8

Longitudinal studies on carotid plaque area in general populations are scarse,3 as well as which risk factors may influence carotid plaque progression. The association between individual cardiovascular risk factors and CVD has been shown to weaken with advancing age.9, 10 The American Heart Association (AHA) has defined ”ideal cardiovascular (CV) health“ by simultaneous presence of 7 ideal health metrics that will be used to measure progress toward AHA’s 2020 goals for CV health.11 The metrics, which include blood pressure, glucose, total cholesterol, BMI, smoking, physical activity and healthy diet, are stratified into ideal, intermediate or poor status and to meet the definition of ideal CV health all the 7 components have to be at ideal level.11 The aim of this study was to evaluate the combined effects of cardiovascular health score, on carotid atherosclerosis extent and progression in an older population with established subclinical atherosclerosis.

Methods

Study population

Individuals invited to participate in this study were participants in Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility (AGES)-Reykjavik study. It is a cohort study initiated in 2002 including 5764 survivors from the Reykjavik study born between 1907 and 1935.12 Baseline data (visit 1) were collected from September 2002 to February 2006 and five years later the follow-up examination (visit 2) was conducted, from April 2007 to October 2011. The invitation to the current study was limited to participants who were scheduled for the follow-up examination from February 2009 to February 2010 and had at least one carotid plaque at visit 1. A total of 1027 individuals came for examination during that period and of those, 925 were eligible for this study. All invited individuals (n=219) agreed to participate. The study was approved by the National Bioethics Committee in Iceland (VSN 00-063) as well as the Institutional Review Board of the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Ageing and the Data Protection Authority in Iceland.

Cardiovascular health metrics

Risk factors were collected at both visits and included blood pressure, total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), triglycerides (TG) and glucose. BMI (weight/height2) was calculated and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol concentration was calculated using the Friedewald formula13. C-reactive protein (CRP) was only measured at visit 1. Questionnaires were used to record smoking status, physical activity, diet and medical history. For information on medication use, participants brought their medication to both visits. Hypertension was defined as the use of antihypertensive medications, self-report from questionnaire, or measurements of systolic blood pressure (SBP)> 140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP)> 90 mm Hg. Diabetes mellitus (DM) was defined as self-report from questionnaire, medication use or fasting serum glucose concentration ≥ 7.0 mmol/L14. History of coronary heart disease (CHD) was defined as previous myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and/or stent obtained from hospital records.15

Cardiovascular health score

Total cholesterol, glucose, blood pressure, BMI and smoking status were stratified according to the AHA definition11 into ideal, intermediate or poor health metrics, coded as 2, 1 and 0 respectively (Supplemental Table 1). Our definition of physical activity and diet varied from the AHA definition. Subjects were questioned how often they participated in moderate or vigorous physical activities in the past 12 months and physical activity > 180 min/wk was defined as ideal, 1–180 min/wk was defined as intermediate, rarely or never participated in physical activity defined as poor.

The AHA diet metric includes the serving size (consumed per day or week) of 5 diet components: fish, fruits and vegetables, fiber-rich whole grains, sugar-sweetened beverages and sodium. 11 In AGES, an unquantified food frequency questionnaire was used to assess dietary habits (Supplemental Table 2). For the current study we could estimate the consumption of all AHA dietary components except sodium. Diet was defined as ideal (4 diet criterions met), intermediate (2–3 criterions met), or poor (0–1 criterions met). Dietary habits were only evaluated at visit 1.

A CV health score was calculated for each subject by summing the score for each metric, resulting in variable with a range from 0–14 (Supplemental Figure 1). Based on the CV health score, subjects were divided into three categories, CV health score ≤ 6 (poor) 7–9 (intermediate) and ≥ 10 (optimal).

Imaging

Detailed description of ultrasound imaging and reading protocols have been published.16 The detailed protocol is in supplement but in brief, images were acquired with Acuson Sequoia C256 with a two-dimensional 8 MHz linear array transducer. Both the near and far walls of the left and right carotid arteries were examined. Images of the carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) were acquired from a predefined 10 mm segment (extending from 10 mm to 20 mm proximal to the tip of the flow divider) of each common carotid artery (right and left artery) at defined interrogation angles using the Meijers Arc. Standard images were obtained from 4 angles at each site. The mean cIMT of the near and far walls was determined from a single image at each interrogation angle for both the right and left CCA. The average of all these cIMT values comprised the cIMT outcome parameter.

A plaque was defined as an isolated thickening at least two times the adjacent normal cIMT by visual assessment19. The Artery Measurement System (AMSII) software (v1.141) was used to assess quantitatively plaque area20 and the K-PACS V1.5.0 software was used to simultaneously compare baseline images to the follow-up images. The plaque boundaries were traced with a cursor on the computer screen and for each plaque outlined the program automatically computed the area (mm2). A longitudinal view of each plaque where the boundaries were clear and the plaque appeared largest was selected for the tracing. Total plaque area (TPA) was calculated by summing the area of all individual plaques.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed for total sample and by sex. CRP and TPA were log transformed to achieve normal distribution. Paired T-test and SAS glimmix procedure, with a random effect for subject,were used to evaluate changes in risk factors between visits. The T-test and the Chi-square test were used for comparison between sexes; and ANOVA to compare CV health score categories. The association between CV health score and log TPA and cIMT at visit 1 was evaluated with general linear regression models, both unadjusted and adjusted for age. Multivariable regression models were used to evaluate the association between factors included in the CV health score and CRP levels with log TPA and cIMT at visit 1.

The effects of CV health score on the change in log TPA and cIMT over 5 years was estimated using a mixed effects regression model, where we included a random effect for subject. The variables sex, age at visit 1, CV health score, time (between visits) and the interaction term CV health score*time were used as fixed effects. The significance of the interaction term was used to estimate if the CV health score modified the change over time in logTPA and cIMT. The effects of medication use (statins and antihypertensives) at visit 1 on the change in TPA and cIMT were also examined using an interaction term with time.

All tests were two-sided and P values <0.05 regarded statistically significant. All statistical analyses were carried out with SAS software version 9.3.

Results

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the study group at both visits. The sample consisted of 66% women, the average age at visit 1 was 75.6 (5.1) years and the average time between visits was 5.2 (0.2) years. The average CV health score was 7.7 (1.9). No participant had all 7 metrics at ideal level, and only 11 (5.0%) had no metric at poor level (Supplemental Table 3). The mean TPA was 49.4 (31.9) mm2 at visit 1 and increased significantly between visits 60.4 (34.7) mm2 (p< 0.001). The mean cIMT was 0.99 (0.14) mm and 0.98 (0.14) mm at visit 1 and visit 2 respectively, but the change was not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants. Data are presented as mean (SD), median (IQR) or number (%)

| Men (n=75) |

Women (n=144) |

Total sample (n=219) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 | Visit 2 | P¶ | Visit 1 | Visit 2 | P¶ | Visit 1 | Visit 2 | P¶ | |

| Age, years | 75.8 (4.8) | 81.0 (4.8) | - | 75.4 (5.3) | 80.6 (5.2) | - | 75.6 (5.1) | 80.7 (5.1) | - |

| TC, mmol/l | 5.2 (1.0) | 4.7 (0.8) | <0.001 | 6.0 (1.1)*** | 5.6 (1.2)*** | <0.001 | 5.8 (1.1) | 5.3 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| LDL, mmol/l | 3.3 (0.9) | 2.8 (0.8) | <0.001 | 3.8 (1.1)** | 3.3 (1.1)*** | <0.001 | 3.6 (1.0) | 3.1 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| HDL, mmol/l | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.4) | ns | 1.8 (0.4)*** | 1.8 (0.4)*** | ns | 1.6 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.5) | ns |

| TG, mmol/l (IQR) | 1.0 (0.–1.4) | 0.9 (0.8–1.4) | ns | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | <0.01 | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | <0.05 |

| Glucose, mmol/l | 5.8 (0.8) | 5.9 (1.0) | ns | 5.6 (0.7)* | 5.6 (0.9)* | ns | 5.6 (0.7) | 5.7 (1.0) | ns |

| CRP, mg/l (IQR) | 2.0 (0.9–3.4) | - | 2.2 (1.1–4.5) | - | 2.2 (1.0–4.3) | - | - | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.5 (3.8) | 26.1 (3.9) | <0.05 | 27.2 (4.5) | 26.4 (4.6) | <0.001 | 26.9 (4.3) | 26.3 (4.4) | <0.001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 145.3 (20.7) | 146.4 (22.3) | ns | 140.4 (18.7) | 145.2 (21.6) | <0.05 | 142.1 (19.5) | 145.6 (21.8) | <0.05 |

| DBP, mmHg | 76.4 (9.2) | 71.2 (11.2) | <0.001 | 71.9 (9.3)*** | 69.5 (10.1) | <0.001 | 73.5 (9.5) | 70.1 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 61 (81) | 67 (89) | ns | 109 (76) | 129 (90) | <0.001 | 170 (77.6) | 196 (89.5) | <0.001 |

| T2DM, (%) | 8 (11) | 16 (21) | <0.01 | 12 (8) | 15 (10)* | ns | 20 (9.1) | 31 (14.2) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status, (%) | ns | ns | ns | ||||||

| Never | 23 (31) | 23 (30) | 61 (42) | 58 (40) | 84 (38.4) | 80 (36.5) | |||

| Former | 45 (60) | 47 (63) | 68 (47) | 76 (53) | 113 (51.6) | 123 (56.2) | |||

| Current | 7 (9) | 5 (7) | 15 (10) | 10 (7) | 22 (10.1) | 16 (7.3) | |||

| Physically active, (%) | 28 (37.3) | 41 (54.7) | <0.05 | 43 (29.9) | 54 (37.5)* | ns | 71 (32.4) | 95 (43.4) | <0.01 |

| CHD, (%) | 21 (29) | 29 (39) | <0.001 | 9 (6)*** | 16 (11)*** | <0.001 | 30 (13.7) | 45 (20.5) | <0.001 |

| Medication use | |||||||||

| Statin use, (%) | 23 (31) | 39 (52) | <0.001 | 28 (19) | 48 (33)* | <0.001 | 51 (23.3) | 87 (39.7) | <0.001 |

| Quit statin use between visits, n | 3 | 3 | |||||||

| Antihypertensive medication use, (%) | 42 (56) | 50 (67) | <0.05 | 85 (59) | 102 (71) | <0.001 | 127 (58.0) | 152 (69.4) | <0.001 |

| Quit antihypertensive use , n | 4 | 4 | 8 | ||||||

| Glucose lowering medication use, (%) | 4 (5) | 6 (8) | ns | 4 (3) | 5 (4) | ns | 8 (3.7) | 11 (5.0) | ns |

| CV health score | 7.1 (1.8) | 6.9 (1.8) | 7.0 (1.8) | ||||||

| B-mode ultrasound | |||||||||

| TPA, mm2 | 50.6 (28.8) | 63.6 (31.4) | <0.001 | 48.8 (33.5) | 58.7 (36.3) | <0.001 | 49.4 (31.9) | 60.4 (34.7) | <0.001 |

| cIMT, mm | 1.03 (0.14) | 1.02 (0.13) | ns | 0.97 (0.13)** | 0.96 (0.14)** | ns | 0.99 (0.14) | 0.98 (0.14) | ns |

P-value from a paired test.

p<0.05;

p<0.01 and

p<0.001 refer to sex difference at visit 1 and visit 2.

TC=total cholesterol; LDL=low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL=high density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG=triglycerides; CRP=C-reactive protein; BMI=body mass index; SBP=systolic blood pressure; DBP=diastolic blood pressure; T2DM=type 2 diabetes mellitus; CHD=coronary heart disease; TPA=total plaque area; cIMT=carotid intima-media thickness.

Women had higher levels of TC, LDL and HDL, but lower glucose levels and less T2DM, physical activity and CHD prevalence at both visits. Statin use was greater in men, but around 70% increase in statin use between visits was seen for both sexes. Treatment for hypertension was similar in both sexes and increased significantly between visits. Men had greater cIMT, but the mean TPA and CV health score were not statistically significant between sexes.

The characteristics of subjects by CV health score ≤ 6 , 7–9 and ≥ 10 at visit 1 are shown in Supplemental Tables 4–6. As to be expected, subjects with poor (≤ 6 ) CV health score had worse risk factors. The prevalence of antihypertensive medication use was greater in subjects with poor CV health score. The prevalence of statin use and CHD was similar across CV health score categories. Furthermore, CRP level was considerably higher in those with poor CV health score (2.8 (1.3–4.8), 1.9 (1.0–3.7) and 1.3 (0.4–1.5) mg/l for those with CV health score ≤ 6 , 7–9 and ≥ 10 respectively, p<0.001).

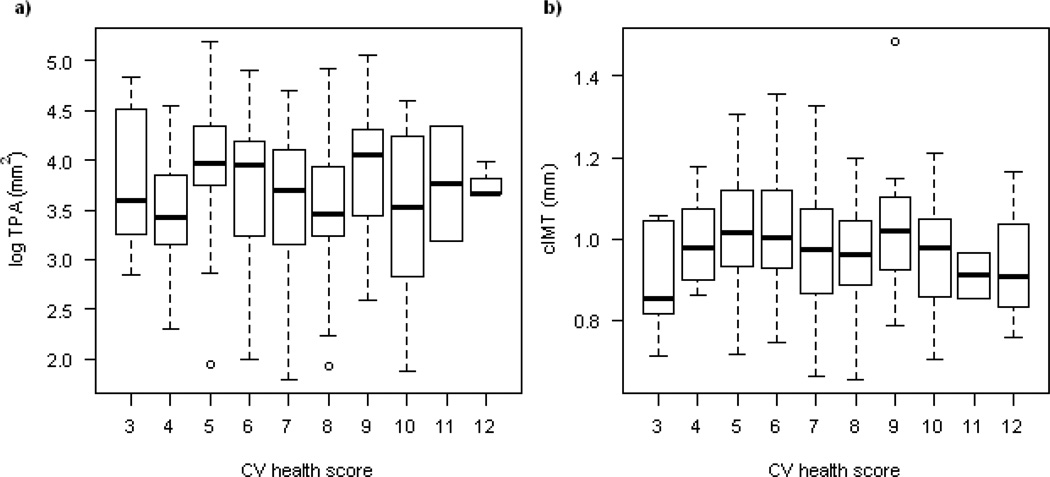

No significant association between CV health score and log TPA or cIMT was seen at visit 1 for the total sample (Table 2 and Figure 1). When sex specific analyses were conducted, men with poor CV health score had greater TPA (mean (SD): 61.5 (32.3), 44.4 (24.2) and 37.7 (23.2) mm2 for those with CV health score ≤ 6, 7–9 and ≥ 10 respectively, p<0.05) than those with optimal (≥ 10) CV health score (Table 2). In linear analysis for men, log TPA was 0.091 mm2 (SE: 0.040, p< 0.05) smaller for each additional point in the CV health score (Supplemental Table 7). CV health score was not associated with TPA in women (0.018 (0.032), p=0.57), or with cIMT in either sex.

Table 2.

The extent and progression of carotid TPA and cIMT by CV health score group at visit 1. Data are presented as mean (SD).

| CV health score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 6 | 7–9 | ≥ 10 | P¶ | |

| Men | n=30 | n=38 | n=7 | |

| TPA, mm2 at visit 1 | 61.5 (32.3) | 44.4 (24.2) | 37.7 (23.2) | <0.05 |

| TPA, mm2 at visit 2 | 75.6 (33.5) | 57.1 (27.7) | 47.7 (26.8) | <0.05 |

| ΔTPA, mm2 | 14.2 (14.5)* | 12.7 (14.3)* | 10.0 (14.4)* | ns |

| cIMT, mm at visit 1 | 1.05 (0.15) | 1.02 (0.13) | 0.98 (0.16) | ns |

| cIMT, mm at visit 2 | 1.04 (0.14) | 1.01 (0.12) | 0.98 (0.16) | ns |

| ΔcIMT, mm | −0.01 (0.07) | 0.00 (0.10) | 0.00 (0.06) | ns |

| Women | n=63 | n=71 | n=10 | |

| TPA, mm2 at visit 1 | 50.0 (34.7) | 47.5 (33.0) | 50.6 (31.8) | ns |

| TPA, mm2 at visit 2 | 59.6 (35.0) | 57.0 (37.9) | 65.1 (35.4) | ns |

| ΔTPA, mm2 | 9.5 (16.6)* | 9.6 (18.2)* | 14.6 (16.9)* | ns |

| cIMT, mm at visit 1 | 0.98 (0.14) | 0.96 (0.13) | 0.93 (0.13) | ns |

| cIMT, mm at visit 2 | 0.98 (0.15) | 0.95 (0.13) | 0.95 (0.13) | ns |

| ΔcIMT, mm | 0.00 (0.09) | −0.01 (0.09) | 0.02 (0.06) | ns |

| Total sample | n=93 | n=109 | n=17 | |

| TPA, mm2 at visit 1 | 53.7 (34.2) | 46.4 (30.1) | 45.3 (28.5) | ns |

| TPA, mm2 at visit 2 | 64.7 (35.2) | 57.1 (34.6) | 57.9 (32.4) | ns |

| ΔTPA, mm2 | 11.0 (16.0)* | 10.7 (16.9)* | 12.7 (15.6)* | ns |

| cIMT, mm at visit 1 | 1.00 (0.14) | 0.98 (0.13) | 0.95 (0.14) | ns |

| cIMT, mm at visit 2 | 1.00 (0.15) | 0.97 (0.13) | 0.96 (0.14) | ns |

| ΔcIMT, mm | 0.00 (0.09) | −0.01 (0.09) | 0.01 (0.06) | ns |

P-value refers to comparison between CV health scores.

The change in TPA is significant between visits (p<0.001).

TPA= total plaque area; cIMT= carotid intima-media thickness, ΔTPA=change in TPA, ΔcIMT=change in cIMT

Figure 1.

The distribution of log TPA and cIMT by the CV health score at visit 1.

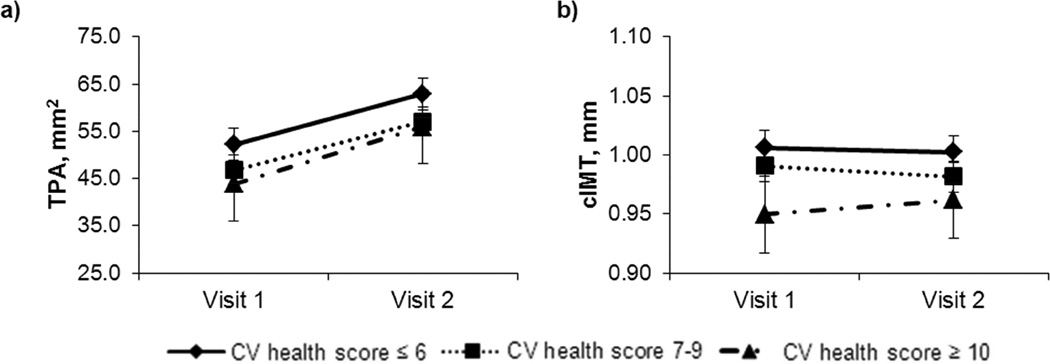

We performed a multivariable mixed model longitudinal analysis to examine whether CV health score (Figure 2), statin or antihypertensive medication use (Supplemental Figures 2 and 3) were predictive of TPA and cIMT progression. None of these factors had an effect on TPA or cIMT progression, because none of the interactions with time were statistically significant, reflected in parallel increase in TPA and cIMT among the CV health score groups.

Figure 2.

CV health score association with TPA (a) and cIMT (b) (least squares mean estimates from mixed models).

Discussion

In this 5 year follow-up study on older subjects with carotid atherosclerosis, the extent and progression of total plaque area (TPA) and cIMT was similar in men and women despite differences in risk factor profiles. The TPA increased considerably between visits but the change in cIMT was not significant. When defined by CV health score, men with poor CV health score had greater TPA than those with better CV health score. However, this association was not detected in women, or with cIMT in either sex. TPA and cIMT progression over 5 years were independent of the CV health score, however men with better CV health score still had smaller TPA at visit 2. Statin or antihypertensive medication use did not affect atherosclerosis progression in this sample of old subjects.

The majority (95%) of participants in this study had poor CV health, where one or more of the CV health metrics was at poor classification. These results are similar to previous studies where only 0–3% of subjects have all CV health metrics at ideal category.17–20 In the ARIC study, 0.2%, 20.9% and 78.9% of white study participants at the age range 45–64 year were categorized as ideal, intermediate and poor CV health respectively.18

Ideal CV health has been inversely associated with cardiovascular events18, and with cIMT in both young19 and middle aged populations.17 To our knowledge no other study has evaluated the association between CV health index and carotid plaque. The current findings suggest that CV health score may be associated with TPA in older men, but is not associated with TPA in older women or with cIMT in either sex. The CV health score did not predict TPA or cIMT progression over 5 years.

In the current study, medication use did not affect the 5 year progression of TPA or cIMT. In a 13-year follow-up study of a general middle aged population, TPA and cIMT progression was significantly lower in long-term users of lipid lowering medications compared with never users.21 To our knowledge, the effects of cardiovascular medical treatment on atherosclerosis progression in older subjects (>65 years) have not been investigated. However studies suggest that subjects in this age group may benefit from treatment14, 22–25. In the AGES-Reykjavik study, statin use was associated with 16% lower cardiovascular mortality, albeit not statistically significant, and 30% lower all-cause mortality in subjects without diabetes.14 In an additional analysis for the current study on the subjects who were still alive at visit 2, the proportion for all-cause mortality had not changed (n=3297, deaths=584 and HR 0.71 (95% CI 0.56–0.90), p<0.01).

In the present study there was no sex difference in TPA or in the progression of TPA or cIMT despite considerable difference in risk factor profiles between men and women. Previous studies have demonstrated greater prevalence and extent of atherosclerosis in men than women at a younger age. However after menopause the development and progression of atherosclerosis is accelerated in women and with increasing age the sex difference is reduced.3, 26 This alteration in sex difference can possibly be explained by changes that occur in cardiovascular risk factor levels over a lifetime. Women have more favorable risk factor profiles than men at a younger age (<50 years), but after menopause this advantage disappears and at older ages women have less favorable risk profiles than men. This change in risk factor burden over time is also reflected in CVD incidence which is greater in men prior to the age of 50 years after which the sex difference is reduced.27 The results presented here support these results.

The weakness of the study is the small study sample and possibly a selection bias for survivors, but the sample only included subjects that had carotid plaque at visit 1 and came for a follow-up examination. B-mode ultrasound imaging can only provide information on the presence and severity of atherosclerosis in peripheral arteries, but large proportion of cardiovascular events are associated with coronary atherosclerosis. 28 However, atherosclerosis is a systemic process and imaging studies have shown that the presence and the extent of atherosclerosis in different arterial sites is significantly correlated.29, 30 The AHA diet metric includes the serving size of five dietary components, but the AGES questionnaire included questions on the frequency of food consumption. Based on these frequency data we estimated the intake of all diet components except sodium, and therefore the diet score used in the current study only included four items. The majority of the subjects in the current study (85%) reported not adding salt to their food on the plate. However, in the national dietary survey on food habits of Icelanders aged 61–80 years, daily sodium intake averaged 3520 (SD 1553) mg and 2474 (SD 1048) mg for men and women respectively.31 These data suggest that approximately 90% of men and 82% of women exceeds the 1500 mg level recommended in the AHA guidelines. We reanalyzed our data by including salt as a component in the diet metric. Inclusion of salt in the diet metric did not notably alter the results. More subjects were categorized with optimal (11.4% vs. 7.8%) and intermediate (53.0% vs. 49.8%) CV health score, but the findings from linear analyses were not altered. The strengths of this study are the community-based design and quantitative longitudinal measurements of atherosclerosis.

Conclusions

To our knowledge this is the first longitudinal study examining effect of the AHA ideal health index on the extent and progression of TPA and cIMT in older people. Men with poor CV health score at the baseline visit had more extensive carotid atherosclerosis than those with optimal CV health score. This association was not detected in women.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We studied carotid plaque area and cIMT progression in old men and women.

We examined cardiovascular health score and carotid plaque area and cIMT.

Carotid plaque area was greater in men with worse cardiovascular health score.

No association was detected in women.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants in the Reykjavik-Ages study for their valuable contribution.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (N01-AG-1-2100), Intramural Research Program, Hjartavernd (Icelandic Heart Association), the Althingi (Icelandic Parliament) and RANNÍS (The Icelandic Research Fund).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Spence JD, Eliasziw M, DiCicco M, Hackam DG, Galil R, Lohmann T. Carotid plaque area - A tool for targeting and evaluating vascular preventive therapy. Stroke. 2002;33(12):2916–2922. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000042207.16156.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebrahim S, Papacosta O, Whincup P, et al. Carotid plaque, intima media thickness, cardiovascular risk factors, and prevalent cardiovascular disease in men and women - The British Regional Heart Study. Stroke. 1999;30(4):841–850. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.4.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herder M, Johnsen SH, Arntzen KA, Mathiesen EB. Risk factors for progression of carotid intima-media thickness and total plaque area: a 13-year follow-up study: the Tromso Study. Stroke. 2012;43(7):1818–1823. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.646596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathiesen EB, Johnsen SH, Wilsgaard T, Bonaa KH, Lochen ML, Njolstad I. Carotid plaque area and intima-media thickness in prediction of first-ever ischemic stroke: a 10-year follow-up of 6584 men and women: the Tromso Study. Stroke. 2010;42(4):972–978. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.589754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plichart M, Celermajer DS, Zureik M, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness in plaque-free site, carotid plaques and coronary heart disease risk prediction in older adults. The Three-City Study. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219(2):917–924. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polak JF, Szklo M, Kronmal RA, et al. The Value of Carotid Artery Plaque and Intima-Media Thickness for Incident Cardiovascular Disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013;2(2):e000087. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polak JF, Pencina MJ, Pencina KM, O’Donnell CJ, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB. Carotid-Wall Intima-Media Thickness and Cardiovascular Events. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(3):213–221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nambi V, Chambless L, Folsom AR, et al. Carotid Intima-Media Thickness and Presence or Absence of Plaque Improves Prediction of Coronary Heart Disease Risk: The ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities) Study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;55(15):1600–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oei H-HS, Vliegenthart R, Hofman A, Oudkerk M, Witteman JCM. Risk factors for coronary calcification in older subjects. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(1):48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beer C, Alfonso H, Flicker L, Norman PE, Hankey GJ, Almeida OP. Traditional Risk Factors for Incident Cardiovascular Events Have Limited Importance in Later Life Compared With the Health in Men Study Cardiovascular Risk Score. Stroke. 2011;42(4):952–959. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.603480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and Setting National Goals for Cardiovascular Health Promotion and Disease Reduction The American Heart Association’s Strategic Impact Goal Through 2020 and Beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris TB, Launer LJ, Eiriksdottir G, et al. Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study: Multidisciplinary applied phenomics. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;165(9):1076–1087. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the Concentration of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Plasma, Without Use of the Preparative Ultracentrifuge. Clinical Chemistry. 1972;18(6):499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olafsdottir E, Aspelund T, Sigurdsson G, et al. Effects of statin medication on mortality risk associated with type 2 diabetes in older persons: the population-based AGES-Reykjavik Study. BMJ Open. 2011;1(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gudmundsson E, Gudnason V, Sigurdsson S, Launer L, Harris T, Aspelund T. Coronary artery calcium distributions in older persons in the AGES-Reykjavik study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012;27(9):673–687. doi: 10.1007/s10654-012-9730-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bjornsdottir G, Sigurdsson S, Sturlaugsdottir R, et al. Longitudinal Changes in Size and Composition of Carotid Artery Plaques Using Ultrasound: Adaptation and Validation of Methods (Inter- and Intraobserver Variability) Journal for Vascular Ultrasound. 2014;38(4):198–208. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulshreshtha A, Goyal A, Veledar E, et al. Association Between Ideal Cardiovascular Health and Carotid Intima-Media Thickness: A Twin Study. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013;3(1):e000282. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Folsom AR, Yatsuya H, Nettleton JA, Lutsey PL, Cushman M, Rosamond WD. Community Prevalence of Ideal Cardiovascular Health, by the American Heart Association Definition, and Relationship With Cardiovascular Disease Incidence. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;57(16):1690–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oikonen M, Laitinen TT, Magnussen CG, et al. Ideal Cardiovascular Health in Young Adult Populations From the United States, Finland, and Australia and Its Association With cIMT: The International Childhood Cardiovascular Cohort Consortium. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013;2(3) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JI, Sillah A, Boucher JL, Sidebottom AC, Knickelbine T. Prevalence of the American Heart Association's "Ideal Cardiovascular Health" Metrics in a Rural, Cross-sectional, Communit-Based Study: The Heart of New Ulm Project. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013;2(3) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herder M, Arntzen KA, Johnsen SH, Eggen AE, Mathiesen EB. Long-term use of lipid-lowering drugs slows progression of carotid atherosclerosis: the Tromso study 1994 to 2008. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;33(4):858–862. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savarese G, Gotto AM, Jr, Paolillo S, et al. Benefits of Statins in Elderly Subjects Without Established Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;62(22):2090–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lloyd SM, Stott DJ, de Craen AJM, et al. Long-Term Effects of Statin Treatment in Elderly People: Extended Follow-Up of the PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER) PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e72642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brugts JJ, Yetgin T, Hoeks SE, et al. The benefits of statins in people without established cardiovascular disease but with cardiovascular risk factors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2009;338 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tinetti ME, Han L, McAvay GJ, et al. Anti-Hypertensive Medications and Cardiovascular Events in Older Adults with Multiple Chronic Conditions. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e90733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allison MA, Criqui MH, Wright CM. Patterns and risk factors for systemic calcified atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(2):331–336. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000110786.02097.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jousilahti P, Vartiainen E, Tuomilehto J, Puska P. Sex, age, cardiovascular risk factors, and coronary heart disease - A prospective follow-up study of 14 786 middle-aged men and women in Finland. Circulation. 1999;99(9):1165–1172. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.9.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics - 2014 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sillesen H, Muntendam P, Adourian A, et al. Carotid plaque burden as a measure of subclinical atherosclerosis: comparison with other tests for subclinical arterial disease in the High Risk Plaque BioImage study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5(7):681–689. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oei H-HS, Vliegenthart R, Hak AE, et al. The association between coronary calcification assessed by electron beam computed tomography and measures of extracoronary atherosclerosis: The rotterdam coronary calcification study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;39(11):1745–1751. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Þorgeirsdóttir H, Valgeirsdóttir H, Gunnarsdóttir I, et al. Embætti landlæknis, Matvælastofnun og Rannsóknastofa í næringarfræði við Háskóla Íslands og Landspítala-háskólasjúkrahús. Reykjavík, Ísland: 2011. Hvað borða Íslendingar? Könnun á mataræði Íslendinga 2010–2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.