Abstract

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive disease caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene. This gene encodes a protein involved in epithelial anion channel. Cystic fibrosis is the most common life-limiting genetic disorder in Caucasians; it also affects other ethnic groups like the Blacks and the Native Americans. Cystic fibrosis is considered to be rare among individuals from the Indian subcontinent. We analyzed a total of 29 world׳s populations for cystic fibrosis on the basis of gene frequency and heterozygosity. Among 29 countries Switzerland revealed the highest gene frequency and heterozygosity for CF (0.022, 0.043) whereas Japan recorded the lowest values (0.002, 0.004) followed by India (0.004, 0.008). Our analysis suggests that the prevalence of cystic fibrosis is very low in India.

Keywords: Allele frequency, cystic fibrosis, India, other populations

Background

Genetic disease or disorder is the result of changes, or mutations, in an individual׳s DNA. Any mutation in the coding region of a gene may lead to the production of a protein which is no longer functional. In India, the occurrence of congenital abnormalities is up to 37.0 per 1000 births and for live births alone from 9.8 to 21.0 per 1000 [1]. Genetic diseases can be inherited if the mutation occurs in the germ cell of the body, as germ cells are involved in passing genetic information from one generation to next generation or from parents to offspring. Cystic fibrosis, an autosomal recessive disease, occurs when both the parents have mutated genes. Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common potentially lethal and life threatening genetic disorder among the white Caucasian population of Europe, North America and Australia. It is caused by mutation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene [2]. In UK approximately 1 in 2500 children are born with CF incidence [3], less common in African Americans (1 in 15 000) and Asian Americans (1 in 31 000) [4].

The CFTR gene translates a protein which transports sodium and chloride across cell membranes. Mutation of CFTR gene leads to too much salt deposit and not enough water within the cells. As a result, the mucus becomes thick, sticky and salty instead of sweaty. The thick, sticky mucus builds up in the respiratory and digestive passage ways, which gives rise to symptoms of the disease condition. The clinical features include pancreatic insufficiency, male infertility, meconium ileus in the newborn, and chronic lung infection with excessive inflammation, leading to progressive deterioration of lung function [5]. The loss of lung function is the main cause of death in CF patients. Most current therapies treat the symptoms of the disease and have increased the median life expectancy for individuals with CF to ~39 years [6].

In 1989 the CFTR gene was identified, and located on the seventh human chromosome at the position 7ql3 [7]. More than 1,900 mutations have been identified in the CFTR gene (http://www.genet.sickkids.on.ca/cftr). The most common mutation is the ΔF508 that is seen in two thirds of all cystic fibrosis cases all over the world [8]. It is a threenucleotide deletion at the 508th codon causing the deletion of a phenylalanine residue and subsequent defective intracellular processing of the CFTR protein which is an important chloride channel [9]. In 1968 it was reported that cystic fibrosis was rare in India [10]. Recent studies on CF cases indicate that the disease is far more common in people of Indian origin than previously thought. CF in the migrant population from the Indian subcontinent in the USA is 1 in 40 000, and in the UK is 1 in 10 000–12 000 [11]. A study on 955 cord blood samples suggested a carrier rate of the common mutation DF 508 (DF 508) as 0.4%, and incidence of CF in India is 1 in 40 000 [12], but its diagnosis often escapes in the majority of cases. In view of the above facts the present study was undertaken to estimate the allele frequency of cystic fibrosis gene in Indian vis-a/-vis 28 other global populations.

Methodology

Data collection:

The data were retrieved from the molecular genetics epidemiology of cystic fibrosis (MGECF) that were published by WHO since 1983. Most documents report joint meetings and workshops organized by WHO in association with various organizations devoted to CF, including the International Cystic Fibrosis (Mucoviscidosis) Association (ICFMA) now Cystic Fibrosis Worldwide, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF), the European Cystic Fibrosis Thematic Network (ECFTN) and the European Cystic Fibrosis Society (ECFS). Some data are collected from the countries of European Union (EU) during 2004.

For the present study we have selected a total of 29 populations of different countries (including India) across different continents i.e, Europe, Australia, Latin America, Africa and Asia. The population data of cystic fibrosis were obtained from the published literature given in Table 1 (see supplementary material) [13–18].

Estimation of allele frequency:

Assuming dominance model with two alleles for cystic fibrosis locus, the recessive allele frequency for different populations was estimated following Hedrick (2005) [19] as

Where, N22 = No. of recessive homozygotes N = Total individuals

The dominant allele frequency (p) was estimated as

ρ =1− q

If ρ and q are the frequencies of a biallelic gene, then at HardyWeinberg equilibrium the frequencies of genotypes are given by

p2 + 2pq + q2= 1

Where, p = the frequency of the dominant allele (represented here by A) q = the frequency of the recessive allele (represented here by a) p2= frequency of AA (homozygous dominant) genotype 2pq= frequency of Aa (heterozygous) genotype q2= frequency of aa (homozygous recessive) genotype

Hardy-Weinberg heterozygosity of a population for a particular locus with n alleles can be estimated as

Where, pi2 = genotype frequency of observed homozygotes.

Heterozygosity is used as an index of genetic variation in a locus within a population and provides information about the occurrence of an allele upon segregation.

Results & Discussion

Genetic study of the allele frequency of loci involved in genetic disorders plays a very crucial role in formulating research projects for follow-up detailed study and in identifying the thrust areas for therapeutic interventions by the governmental agencies. Based on allele frequency analysis it can be predicted how frequently the diseased condition will occur in common population of a country. The population size and incidence of cystic fibrosis in 29 countries are presented in Table 1 (see supplementary material).

Assuming a digenic model with complete dominance and a recessive allele governing the cystic fibrosis condition, we analyzed 29 human populations for estimating the frequencies of normal/dominant (healthy condition) and recessive (diseased condition) alleles and the extent of heterozygosity for cystic fibrosis locus. Heterozygosity is used as an index for understanding the degree of genetic variation occurring in a diseased locus. Greater the heterozygosity, greater the chance of occurrence of the disease as recessive homozygotes upon Mendelian segregation and recombination in a population.

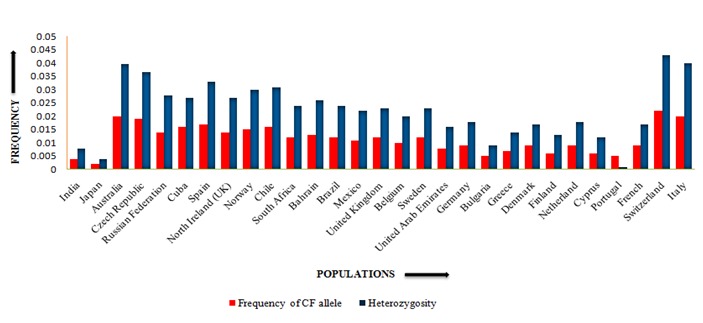

The gene frequency and heterozygosity for cystic fibrosis in 29 countries is presented in Figure 1. Earlier study on cystic fibrosis reported it be rare in India [10]. But subsequent studies reported that cystic fibrosis increases every year in the population. Keeping this point in mind, we estimated the frequency of the recessive allele for cystic fibrosis in 29 global populations including India from the genotypic frequencies. Our analysis revealed that Japan recorded the lowest allele frequency and heterozygosity for CF (0.002, 0.004) followed by India (0.004, 0.008).

Figure 1.

Comparison of gene frequency and heterozygosity for cystic fibrosis in India and 28 global populations

The predicted incidence for CF among Asians in the United Kingdom (Indians/ Pakistani) is 1 in 10000 [20] and 1 in 40000 in the USA [11]. But in India, the CF incidence is reported to be 1 in every 40000 to 100000 live births [21]. Switzerland (0.022, 0.043), Italy (0.020, 0.040) and Australia (0.020, 0.039) record relatively higher frequency of the recessive allele and heterozygosity for CF Table 2 (see supplementary material). It is evident from our analysis that Asian countries showed lower frequencies of the CF recessive allele compared to European countries like Switzerland and Italy.

Literature on the study of CF in Middle East countries is scanty. Our analysis revealed that the Middle East countries namely UAE (0.008, 0.016) and Bahrain (0.013, 0.026) had intermediate CF recessive allele frequency and heterozygosity. The global distribution pattern of the CF recessive allele frequency and heterozygosity (Figure 1) provides a clue that during the process of migration of human population from Africa to other continents, the frequency of CF recessive allele might have increased in the colder regions of the world due to natural selection. Till date there is no detailed study on the genetic and clinical profile of cystic fibrosis among Indian children [22]. Thus, an in-depth study on CF across the global populations at molecular level could provide further insights in understanding the occurrence of CF cases across different populations all over the globe.

Conclusion

The present study revealed that the recessive allele frequency and heterozygosity for cystic fibrosis are low in India i.e., 0.004 and 0.008, respectively. But Japan recorded the lowest values for allele frequency and heterozygosity (i.e. 0.002, 0.004) whereas Switzerland had the highest recessive allele frequency and heterozygosity (i.e. 0.022, 0.043) for cystic fibrosis. India runs a relatively low risk for cystic fibrosis among twenty-nine global populations. Further research at molecular level may be initiated to understand the factors responsible for increased frequency of cystic fibrosis in European countries and decreased frequency in Asian countries.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Assam University for providing the necessary facilities to undertake the research work. The work was not funded by any external funding agency.

Footnotes

Citation:Bepari et al, Bioinformation 11(7): 348-352 (2015)

References

- 1.Malakar AK, et al. IJSR. 2014:2136. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kraemer R, et al. Respir Res. 2006;7:138. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dodge JA, et al. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77:493. doi: 10.1136/adc.77.6.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamosh A, et al. J Pediatr. 1998;132:255. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zielenski J. Respiration. 2000;67:117. doi: 10.1159/000029497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashlock MA, Olson ER. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:107. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-061509-131034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerem B, et al. Science. 1989;245:1073. doi: 10.1126/science.2570460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flume PA, Stenbit A. Am J Med Sci. 2008;335:51. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31815d2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morales MM, et al. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1999;32:1021. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X1999000800013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehta S, et al. Indian Pediatr. 1968;5:185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powers CA, et al. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:554. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170300108024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapoor V, et al. J Cyst Fibros. 2006;5:43. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dodge JA, et al. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:522. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00099506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung F, et al. Respir Med. 2002;96:963. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2002.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucotte G, et al. Hum Biol. 1995;67:797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slieker MG, et al. Chest. 2005;128:2309. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yiallouros PK, et al. Clin Genet. 2007;71:290. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Southern KW, et al. J Cyst Fibros. 2007;6:57. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedrick PW, Goodnight C. Evolution. 2005;59:1633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodchild MC, et al. Arch Dis Child. 1974;49:739. doi: 10.1136/adc.49.9.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabra SK, et al. Indian Pediatr. 2003;40:612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kabra M, et al. Am J Med Genet. 2000;93:161. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20000717)93:2<161::aid-ajmg15>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.