Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

to understand the family's experience of the child and/or teenager in palliative care and building a representative theoretical model of the process experienced by the family.

METHODOLOGY:

for this purpose the Symbolic Interactionism and the Theory Based on Data were used. Fifteen families with kids and/or teenagers in palliative care were interviewed, and data were collected through semi-structured interviews.

RESULTS:

after the comparative analysis of the data, a substantive theory was formed "fluctuating between hope and hopelessness in a world changed by losses", composed by: "having a life shattered ", "managing the new condition", "recognizing the palliative care" and "relearning how to live". Hope, perseverance and spiritual beliefs are determining factors for the family to continue fighting for the life of their child in a context of uncertainty, anguish and suffering, due to the medical condition of the child. Along the way, the family redefines values and integrates palliative care in their lives.

CONCLUSION:

staying with the child at home is what was set and kept hope of dreaming about the recovery and support of the child's life, but above all, what takes it away even though temporarily is the possibility of their child's death when staying within the context of the family.

Keywords: Palliative Care, Family, Bereavement, Child

Introduction

The advances in health care contribute to a new scenario, in which the possibility of curing diseases became the rule rather than the exception. This new context made it possible to reduce the number of deaths due to premature complications, and increased the life expectancy of children with chronic diseases as well as providing an increased cure rate of pediatric oncological diseases( 1 - 2 ).

Despite the increase of the survival of children with the most diverse pathologies, part of these patients do not manage to recover and benefit from palliative philosophy. From this moment on, patient, family and the healthcare team will face a challenge in the pursuit and implementation of conducts to improve the quality of life through pain relief, symptom management and psychosocial and spiritual needs( 1 , 3 - 4 ).

It is worth noting that not every child who receives palliative care is in the final stage of life; This philosophy of care can and must be concomitant to intervention intended to cure or stabilize the disease in relation with the prolongation of life( 3 ).

In this view, children with conditions that threaten or limits their life and their families are unique. The burden of care, associated with the progression of the disease, has profound effect on all dimensions of family life, affecting the emotional, psychological, physical and financial parts. As a result, the whole family structure and organization is changed, besides having a great influence on their well-being( 1 , 3 , 5 - 6 ).

The families, in the management of palliative care of the child, know that they are in a process of transition between having the ch11ild alive and with controlled symptoms or no longer having the child physically present in the family. The way the family adjusts to managing the disease situation can be influenced by social support, by beliefs and the child's condition (7) in addition to the parent's involvement in the care of the child, seeking autonomy in decision making situations (8).

Thus current study aims to understand the experience of the family of the child and/or teenager who's in palliative care. Without a clear understanding of the meaning that the family gives to the experience of having a child in palliative care and how to interpret and define the situation, little can be done to support professionals in achieving significant care in the life of the child and/or teenager and the family's mourning.

Methodology

This study, with a qualitative approach, made use of the Symbolic Interactionism as theoretical referential. This focuses on the nature of the interactions, dynamics of social activities between people, and the meanings they ascribe to events, natural environments in which they live and actions they perform. The methodological frame of reference was the Theory Based on Data, a method that guides the data collection, organization and analysis of data and indicates a set of well-developed and systematically interrelated categories, to form a theoretical framework to explain relevant phenomena, such as those related to the experiences of health and illness( 9 ).

The data were collected in the clinic of Pain and Palliative Care unit of a public hospital in the city of São Paulo, tertiary level, with characteristics of teaching and research. The service exists for 13 years and provides assistance to children and teenagers, people with different pathologies, who receive curative therapies, pathology control and also children and/or teenagers who receive exclusive palliative therapy. It is formed by a multidisciplinary team, composed by doctors, a nurse, a physiotherapist, a dentist, an occupational therapist, a psychologist, a social worker, a nutritionist and a speech therapist. The institution has no home care service for children and/or teenagers in palliative care and their families. The outpatient care occurs in three periods of the week, on pre-scheduled dates, or family request.

The institution does not have a specific hospitalization unit for patients in palliative care. When hospitalization is necessary, children and/or adolescents are hospitalized in available beds at the wards and helped by the palliative care and specialty to which they belong. The inclusion of a patient in Pain and Palliative Care is performed by the referral of patients and family members for several medical specialties that meet the child and/or teenager for his basic pathology, through telephone contact and/or medical appointment request, and depending on the family's acceptance regarding performing the treatment.

The families of children and/or teenagers in palliative care that have participated in this study met the following inclusion criteria: the child and/or teenager has to be in monitoring or have been accompanied by Pain and Palliative Care, the child and/or teenager with a "limiting condition of life" or a "life threatening" condition, documented in their chart and that the family had been informed by the health team that there is no chance of recovering from the disease, which also should be documented in the clinical record.

The initial access to the families came through the monitoring of the ambulatory care and hospitalization unit visits, effectuated by the team of Pain and Palliative Care. The approach to these families was made at random and personally by researchers in the outpatient unit, while the families were waiting for the service of the Group of palliative care or out-patient consultation. In the case of hospitalization, the first approach was made by the medical unit of Pain and Palliative Care, with the objective of asking the mother's authorization in order for the researcher to inform about the research From this consent, the researchers presented the inpatient unit to perform the approach.

Were also approached families whose son had died and had been accompanied by the Pain and Palliative Care. Despite not having an established protocol by the group to attend to these families in situation of postmortem, some families still maintained contact with the Group of Palliative Care, mainly through telephone conversations and when prompted, are met by the team on pre-scheduled dates. This last sample group allowed extending the meaning of the experience of these families, especially regarding end-of-life issues and grieving. It is noteworthy that, with the development of more than one sample group, it is possible to maximize the differences, allowing the development of variations in theory and increasing its explanatory power (9). .

In this study 15 families with children and/or adolescents in hospital care have participated, being 10 patients with oncological diseases and 5 with no oncological diseases: degenerative neuropathy, myelopathy associated with HTLV, myelomeningocele and cerebral palsy, dermatopolimiosite and xeroderma Pigmentosum. In total, there were 20 family members interviewed, distributed as follows: 15 mothers, 3 fathers, 1 grandfather and 1 paternal aunt. The contact for the invitation to participate in the survey was made to the mother of the child/adolescent in all cases because it was the person who, for the most part, was present at the clinic or hospital with the child/adolescent. Many of these mothers pointed out at the time of the call, the active participation of other family members in the care of the child during the moment of treatment and therefore, the invitation has been extended to other components of the familiar nucleus directly involved with the care of the child and/or teenager in this phase of treatment. In the cases of children who passed away, it was the mother who still kept contact with the Palliative Care team.

In relation to children and teenagers in palliative care, nine were female and six were male; they had at least one brother, with the exception of only one of the children, who was an only child. They were between the ages of 2 and 20 years, with time of the diagnosed diseases ranging from 2 months to 13 years. The inclusion time and follow-up of these children and/or teenagers in the Pain and Palliative Care unit varies from 1 month to 3 years.

The data collection period was between January 2010 and March 2011. The adopted strategy for the collection was the semi-structured interview held until it was recognized the theoretical saturation, when they verified repetition, absence of new data and increasing understanding of the identified( 9 ) concepts. Thus, the number of families was forming as a result of the analysis of their testimony. As data analysis progressed, new data was sought out, so the categories would be well developed and dense, which led to the inclusion of families who already had been accompanied by the palliative care team, but their child had already dead.

The interviews were recorded and are approximately 40 to 150 minutes. The guiding question was: "Tell me how it is for you taking care of your child in palliative care at home". The interviews were conducted simultaneously with the data analysis, which inspired new questions, such as: "How is everyday life with your child in palliative care? Who helps you with the care? What is more difficult? What is easier? What do you say when talking about this disease? How do you imagine the future? ".

The open encoding was the first part of the analysis. The text of each interview was fragmented into small sections and examined line by line, enabling the identification of codes. From here onwards, the data were compared in search of similarities and differences and grouped into categories. In the second step of the analysis, axial coding, the categories were related to its subcategories until theoretical saturation had been reached. In this step, we used the General model called the "six C's" (causes, context, contingencies, consequences, conditions and covariant). This model helps to broaden the analysis, so that the presentation of data wouldn't be limited to a listing of codes or categories (10). The encoding setting, the third step of the analysis, is realized in the search to integrating and refining the theory (9).

Considering the construction of a theory based on the data, the results are presented as a set of interrelated concepts, through the drafting of a plot(9), for the presentation of the theoretical model explaining the process.

It should be noted that data collection was initiated by the favorable opinions of the Research Ethics Committee of the school of nursing of the University of São Paulo (Case No. 739/2008) and the Research Ethics Committee of the institution at the end of the study (case No. 748/40/2008).

Results

The identified categories and theoretical established relations made it possible to develop an analytical process and explanation of actions and interactions that form the experience of the family of the child and/or teenager in palliative care.

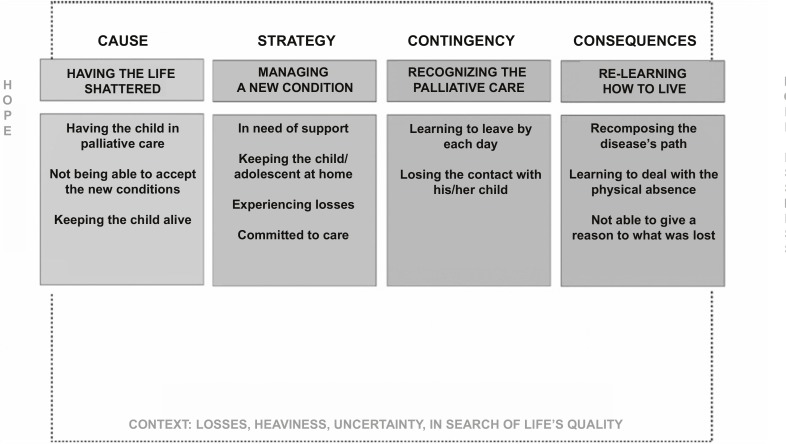

The process contains four sub-processes that represent the symbolic significance of the experience for the family of the child and/or teenager in palliative care, in a context of loss, grief, uncertainty and search for quality of life. Each identified sub-process gave cause for the categories: having a life shattered, managing the new condition, to acknowledge the palliative care and relearning to live.

The analysis of these categories and the way they interact with the experience of the family permitted to identify the central category: fluctuating between hope and hopelessness in a world changed by losses. The integration between the categories and its articulation with the central category made the construction of a theoretical model, as shown in Figure 1, which represents the experience of the family in relation with the experience regarding the care of a child in palliative care.

Figure 1. Representation of the Theoretic Model Diagram: fluctuating between hope and hopelessness in a world changed by the losses.

The substantive theory

The experience begins with the family having a shattered life, characterized by the news of the child and/or teenager in palliative care.Having the child in palliative care exposes the family to a new reality: that the existing drug treatment is not sufficient to prevent or control the spread of the disease, which is not easily understood and accepted by the family. Surprised by the new condition, they are worried about the prognosis and afraid of the child's possible physical suffering. This news is the cause of the process about the meaning of having a child with no possibility of curative therapy, represented by the unawareness of the causes of the transition of the treatment and the absence of resources to understand it.

The family's experiencing change and finding resources to understand the new realitycannot accept the new condition of the child, that is, they can't imagine the loss of their child, which is incoherent and unjust after what they have been through. For her, it is as if the team has abandoned the child and/or teenager and has given up the battle against the illness. Believing that the health team was wrong about the somber prognosis of the child, sustains the hope of the recovery and remains proactive to find resources in order to keep the course of history with the imagined future after the cure of the disease. That is why questioning the team about new forms of treatment for the child is considered as a way to keep the child alive.

The actions and strategies developed by the family of the child and/or teenager in palliative care, in order to achieve a balance between meeting the demands of the disease and the preservation of family routine, are represented by the categoryhandling the new condition. Hope is something that deviates from the fear of losing their child and keeps the family focus of care for the child and/or teenager, offering them the best quality of life and control of symptoms. So they keep hope of recovery, control or delay the progression of the disease and act with the purpose to preserve the child in the most comfortable way.

Hence, keeping the child at home and engaging in the care they can preserve the quality of life and family structure, maintaining the family's daily life as close to normal as possible. However, during this trajectory, the family is confronted with multiple and successive loss that may affect the physical, emotional, financial, social and financial sphere of the family unit.

Experience loss is one of the components of the sub-process which approaches the family of the new reality and the possibility of their child's death that has physical limitations and therefore the family feels that they're losing control over the disease. Realizing the need of support for the family, they search for help in palliative care or group and requests admission of their child to hospitalize, episodes that at are more frequent every time.

The received social support influences the family in the process of dealing and coping with adversity due to advancements of the disease. The meanings emerge starting from interactions between the family experience and with their child, with the health team and with the social environment. Being recognized and supported in their journey of care, makes the family feel hopeful to move forward in the struggle of maintaining the life of their child. On the other hand, failing to find help centers, especially in relation to the team, makes them feel overloaded and above all, alone in their battle for the life of their child. Therefore, suffer quietly and look strong, especially in front of the child, even if they are being shattered by the pain of the possibility of losing him.

The whole of experiences shows the factors that can help or inhibit the family torecognize palliative care, which is eventually the process where they are living in uncertainty between the possibility of recovery or death of the child. In the experience of palliative care, the family realizes some benefits to in relieving physical discomfort of the child, through realized interventions. This allows them to move on with less suffering. However, recognizing palliative care, the family also faces uncertainty, anguish and regret, because they're living with the possibility of imminent death. The uncertainty, considerably present in this process, prevents the definition regarding the legitimacy of the medical position of the child and/or teenager in palliative care. Still, the family will not be intimidated by this new reality of palliative care, because they believe that this is the only path that leads to staying close with the child for some time.

The possibility of their child's death is disturbing for the whole family and makes it difficult to imagine a future without the child and/or adolescent in the family; this is why their focus should always be directed to the present. The family learns to think about the future without their child and necessarily releasing the energy, so they learn to live one day at a time.

The child and/or teenager actively participates in the struggle of searching for treatment and well-being until he/she finds himself physically and emotionally exhausted, and is able to express his/her feelings and wishes to the family, when he/she finds a space. The family realizes that they're losing connection with their child, when he, courageously, expresses his desire to stop fighting, to rest and die. The child's physical and emotional suffering will appear a perceived lack of will to live, and hopelessness, the family will come to the conclusion that their connection has come to an end. This is a condition that allows the family to consider the impossibility of recovery and realize the reality of the impending death of their child. In this manner, the family lives the ambivalence between the desire to stop the suffering of their child, and to prevent death at any cost, recognizing that right now, regardless of their efforts, they are unable to reverse the picture and get them out of this situation. Consequently, feeling helpless, anguished and at the same time aware of the fatigue and the lack of strength to endure and witness this atrocious suffering.

On one hand, the family seeks a help center to restore their energy and keep fighting together, on the other hand talking about their child's death is not accepted by many of them. Verbalizing death means they complete the hopelessness and defeat, so in some cases the pact of silence should be chosen. Their pain is now related to time that can still be counted on the presence of their child. Living with the uncertainties emerging from the daily possibility of loss until this actually happens.

The consequence of this process is part of their child's death. At that stage, the family, regarding reconciling the disease's trajectory, develops policies to alleviate the suffering and anguish, seeking the meaning of the experience. The lack of reception and the impossibility of finding a meaning for their loss marks the result of the process experienced by the family. In this sense, the need to relearn how to live contains less suffering when you can enjoy confidence and moments of saluting, especially with the requested health team. In this you will find meaning in the lived experience and they willlearn to deal with the physical absence of their child, to identify new ways to keep it alive within their family home.

Fluctuating between hope and hopelessness in a world changed by lossesrequires the family to undergo a restructuring of life changed by its biggest loss: the death of their child.

Discussion

This study is consistent with the literature, which shows the attempt to keep the family activities as close to what they have experienced previously. In the context of palliative care, it's about the maximum they are allowed to do and, thus, can continue living and maintaining their family unit through the rupture and the chaos already established (3, 5.11). Moreover, this caution reflects the importance for the family that the child continues to live despite the difficulties and limitations with the progression of the disease (12-13).

Preferably at that stage, is staying home as much as possible, feeling the fear of the appearance of symptoms and the lack of ability to manage them, as well as the concern to provide the best for the child and for the other family members. The decision to keep the child at home also comes back in the kind of support they would receive associated to the health team with the difficulty and fear of not being able to cope with the appearance of more symptoms (7.13).

This work allows to state that these families could stay with the child in their adjusted home and keep their hope to continue dreaming about the recovery and maintenance of the child's life, but above all, separating temporarily the possibility of their child's death in the context of the family.

Despite the difficulty of obtaining a consensus on the definition of hope, it is portrayed by most studies as a State related to a positive Outlook about the future (14). In this way, it is a complex, multidimensional and dynamic phenomenon that can be influenced by a number of factors, including health professionals (15). In this study, the family's expectation of its goal - the recovery of its child or a slow progression of the disease as much as possible, alleviating suffering and improving the quality of life - which keeps it firmly in its purpose to continue taking care of their child and looking for resources to achieve their goal.

Thus, this study is consistent with the literature that identifies the hope as a central concept, both for those who are sick and for the people around the patient. It is also important to go through the experience and respond to a serious disease established by human resources used as a coping strategy for people with different diseases (15-18). In the context of palliative care, the importance of hope as a positive experience for patients and their families has been discussed in the literature (19) and appears as fundamental in the way patients and their families will live during the final stages of life.

Although the family always tries to keep their faith, at certain times periods of hopelessness will occur, particularly regarding the crises emerging from the exacerbation of the disease relapses in case of oncological diseases when witnessing the suffering of their child and its resignation to live. However, even facing these periods of adversity they try to focus their efforts on the positive results that come from getting so far in the management of child care and with it, keep alive the hope that can continue regarding the way for the preservation of life.

The progression of symptoms and the possibility of not being able to control them with the consequential increase of their suffering, is one of the major concerns of the family( 1 , 4 , 20 ), which has been proven in this study representing an additional load of suffering to feel unable to have this control. However, by acknowledging the palliative care the opportunity to control symptoms and improve and maintain their quality of life is seen.

To live the experience of having a child in palliative care, despite the sense of loss is presented throughout the journey of the disease, which can be proven by the data of this research. In fact, these usually tend to be recognized after the death when you lose the unique relationship that is perceived as vital for the people who have this experience (21). Coping with these feelings, in advance, it is difficult and scary for parents with children in the final stage of life. The need to be able to prevent the death of the child is enormous, but not all parents are willing to avoid losing at any cost. Some of them can make their feelings of loss with the goals aimed for the well-being of the child and/or teenager, recognizing that its death might be the best solution to prevent the continuation of suffering (22).

Therefore it is important that the family can start its recovery, firstly to construct the reality of her child's death (23). To do so, you have to stop thinking, feel, relate and talk about her; however, there are only few people who can handle the early verbalization of death. On this journey, it seems to be easier to live with the uncertainties to acknowledge the child and/or teenager soon will not survive (24).

Therefore, it is up to professionals with compassion and solidarity, to reduce the impact of adversity of illness by providing relief of suffering and the formation of new perspectives for the family (25). In this way, we believe it is the responsibility of the nurse to seek assistance to find a way to regroup the family that tries cope with the demands and changes that occurred regarding palliative care and in order to intervene the intention of recovering the balance of the family system. In order for the possible evaluation and intervention with families to become concrete, it is necessary to create a context in which professionals and families will be able to establish a partnership, trust, transparency and regular communication (23).

Final considerations

The study has shown that recognizing palliative care is an uphill battle for the family, since it puts them in uncertainty and regarding the future and the possibility of death. The narrative of the family, recognizing the benefits of palliative care does not mean accepting death because this is a reality that they will never be accepted, but it is their way of dealing with loss along the way and keep their hope and perseverance, to focus on the management of child care. This means that the family experiences the sense of loss over the journey of the disease and not just after their child's death, what needs to be recognized by the professional who is attending them.

Thus, this study in conjunction with literature, demonstrates that the family can find a new way to continue living despite the loss in which the process of experiencing the palliative care and the consequent death of the child occurs with less conflict. But this is only possible when the context admits the recognition of suffering, doubt, offers appropriate information, and allows a space where the family can share ideas, feelings and facilitates access to social support. These conditions need to be respected, when working with the family, so that it allows its members to give meaning and construct a new reality regarding the experiences and interactions where they can support each other and seek to decrease the suffering existing in these experiences (23). This caring of the family, which should be carried out gradually during the path of palliative care, will reflect in their confrontation of later formulations regarding the issues of grief and death and how they will lead their life after the death of their loved one.

Footnotes

Paper extracted from doctoral dissertation "The experience of the family of a child/teenager requiring palliative care: fluctuating between hope and hopelessness in a world transformed by loss", presented to Escola de Enfermagem, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. Supported by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Brazil, process # 4963/10-5

Referências

- 1.Bergstraesser E. Pediatric palliative care-when quality of life becomes the main focus of treatment. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;172(2):139–150. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1710-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Shea ER, Bennett Kanarek R. Understanding pediatric palliative care: What it is and what it should be. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2013;30(1):34–44. doi: 10.1177/1043454212471725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monterosso L, Kristjanson LJ. Supportive and palliative care needs of families of children who die from cancer: an Australian study. Palliat Med. 2008;22(1):59–69. doi: 10.1177/0269216307084608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knapp CA, Madden VL, Curtis CM, Sloyer P, Shenkman EA. Family support in pediatric palliative care: how are families impacted by their children's illnesses? . J Palliat Med. 2010;13(4):421–426. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price J, Jordan J, Prior L, Parkes J. Living through the death of a child: a qualitative study of bereaved parents' experiences. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(11):1384–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foreva G, Assenova R. Hidden patients: the relatives of patients in need of palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(1):56–61. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bousso RS, Misko MD, Mendes-Castillo AM, Rossato LM. Family management style framework and its use with families who have a child undergoing palliative care at home. J Fam Nurs. 2012;18(1):91–122. doi: 10.1177/1074840711427038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melo EMOP, Ferreira PL, Lima RAG, Mello DF. The involvement of parents in the healthcare provided to hospitalzed children. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem. 2014;22(3):432–439. doi: 10.1590/0104-1169.3308.2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strauss A, Corbin J. Pesquisa qualitativa: técnicas e procedimentos para o desenvolvimento de teoria fundamentada. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glaser BG. Getting Out of the Data: Grounded Theory Conceptualization. Mill Vallye: Sociology Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Titus B, de Souza R. Finding meaning in the loss of a child: journeys of chaos and quest. Health Commun. 2011;26(5):450–460. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.554167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menezes A. Moments of realization: life-limiting illness in childhood-perspectives of children, young people and families. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2010;16(1):41–47. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2010.16.1.46182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zelcer S, Cataudella D, Cairney AE, Bannister SL. Palliative care of children with brain tumors: a parental perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(3):225–230. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kylmä J, Duggleby W, Cooper D, Molander G. Hope in palliative care: an integrative review. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7(3):365–377. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duggleby W, Holtslander L, Kylma J, Duncan V, Hammond C, Williams A. Metasynthesis of the hope experience of family caregivers of persons with chronic illness. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(2):148–158. doi: 10.1177/1049732309358329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McClement SE, Chochinov HM. Hope in advanced cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(8):1169–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutherland N. The meaning of being in transition to end-of-life care for female partners of spouses with cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7(4):423–433. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berendes D, Keefe FJ, Somers TJ, Kothadia SM, Porter LS, Cheavens JS. Hope in the context of lung cancer: relationships of hope to symptoms and psychological distress. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(2):174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holtslander LF. Ways of knowing hope: Carper's fundamental patterns as a guide for hope research with bereaved palliative caregivers. Nurs Outlook. 2008;56(1):25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kars MC, Grypdonck MH, Beishuizen A, Meijer-van den Bergh EM, van Delden JJ. Factors influencing parental readiness to let their child with cancer die. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54(7):1000–1008. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreicbergs UC, Lannen P, Onelov E, Wolfe J. Parental grief after losing a child to cancer: impact of professional and social support on long-term outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(22):3307–3312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kars MC, Grypdonck MH, de Korte-Verhoef MC, Kamps WA, Meijer-van den Bergh EM, Verkerk MA. Parental experience at the end-of-life in children with cancer: 'preservation' and 'letting go' in relation to loss. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(1):27–35. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0785-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bousso RS. Um tempo para chorar: A família dando sentido à morte prematura do filho [Livre-Docência] São Paulo: Escola de Enfermagem, Universidade de São Paulo; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenblatt PC. Parent grief: narratives of loss and relationship. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis Group; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Remedi PP, Mello DF, Menossi MJ, Lima RAG. Cuidados paliativos para adolescentes com câncer: uma revisão da literatura. Rev Bras Enferm. 2009;62(1):107–112. doi: 10.1590/s0034-71672009000100016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]