Abstract

Background:

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has recently highlighted mental health concerns in student athletes, though the incidence of suicide among NCAA athletes is unclear. The purpose of this study was to determine the rate of suicide among NCAA athletes.

Hypothesis:

The incidence of suicide in NCAA athletes differs by sex, race, sport, and division.

Study Design:

Retrospective cohort study.

Level of Evidence:

Level 3.

Methods:

NCAA Memorial Resolutions list and published NCAA demographic data were used to identify student-athlete deaths and total participant seasons from 2003-2004 through 2011-2012. Deaths were analyzed by age, sex, race, division, and sport.

Results:

Over the 9-year study period, 35 cases of suicide were identified from a review of 477 student-athlete deaths during 3,773,309 individual participant seasons. The overall suicide rate was 0.93/100,000 per year. Suicide represented 7.3% (35/477) of all-cause mortality among NCAA student athletes. The annual incidence of suicide in male athletes was 1.35/100,000 and in female athletes was 0.37/100,000 (relative risk [RR], 3.7; P < 0.01). The incidence in African American athletes was 1.22/100,000 and in white athletes was 0.87/100,000 (RR, 1.4; P = 0.45). The highest rate of suicide occurred in men’s football (2.25/100,000), and football athletes had a relative risk of 2.2 (P = 0.03) of committing suicide compared with other male, nonfootball athletes.

Conclusion:

The suicide rate in NCAA athletes appears to be lower than that of the general and collegiate population of similar age. NCAA male athletes have a significantly higher rate of suicide compared with female athletes, and football athletes appear to be at greatest risk.

Clinical Relevance:

Suicide represents a preventable cause of death, and development of effective prevention programs is recommended.

Keywords: suicide, NCAA, student athlete, sudden death

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) recently highlighted mental health concerns of student athletes as an area requiring further attention, citing a gradual increase in suicide rates and increase in the type, percentage, and severity of depression in young adults.17 Suicide represents the third leading cause of death among college-age individuals and the second leading cause of death among college students.5,14 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports a suicide incidence of 11.6/100,000 for individuals aged 18 to 22 years, while studies of suicide among college students demonstrate an incidence of 7.5/100,000.4,19

Multiple studies have reviewed the effects of athletic participation and exercise on depression and suicidality with varying conclusions. Athletes have substantially higher self-esteem and social connectedness while exhibiting lower levels of depression than nonathletes.1,6 Participation on a college sports team significantly reduces the likelihood of seriously considering, planning, or attempting suicide.3 Male nonathletes were 2.5 times as likely to be suicidal than their athlete peers, while female nonathletes were 1.67 times as likely to report suicidal behavior as their athlete peers. Others have pointed to an athlete’s willingness to participate more frequently in risk-taking behaviors,10,16,18 inferring that the increased pressure of competitive sport, concerns around the inability to participate related to injury, and a willingness to engage in high-risk behaviors may elevate an athlete’s risk of depression and suicidality.2,8,20

The incidence of suicide in NCAA athletes has only been reported as part of larger studies of sudden death.9,13 The purpose of this study was to determine the rate of suicide among NCAA athletes and identify differences in the incidence of suicide with regard to age, sex, race, division, and sport.

Methods

This was a retrospective review of NCAA student-athlete deaths beginning 2003-2004 through the 2011-2012 academic years. The NCAA reports participation data in its Student Athlete Ethnicity Report.23 Approximately 450,000 student athletes participate annually in an NCAA-sanctioned sport. For this study, a student athlete was defined as any individual registered as a participant in an NCAA-sanctioned sport across any of the 3 NCAA Divisions (I, II, and III).

Cases of death were identified from the NCAA Memorial Resolutions database, which is compiled annually in memory of NCAA student athletes and staff having died of any cause. Institutions voluntarily contribute cases to this database, though no cause of death is attributed at the time of reporting. Internet searches were performed to investigate case details, including age, sex, race, and the circumstance and cause of death. Suicide was defined as an intentional self-inflicted injury that caused death. Confirmed intentional self-inflicted death was only ascribed if suicide was stated as a cause of death in the reference article. Cases of suspected suicide were designated if the reference article attributed suspected suicide as a cause of death. We excluded all other causes of mortality or any case of death suspected to be unintentional (ie, unintended drug overdose, accidental death).

A univariate chi-square analysis was used to compare athlete suicide rates by sex, ethnicity, NCAA division, and sport. Mortality rates were calculated using NCAA participation numbers acquired from the NCAA Student Athlete Ethnicity Report, and exposure was defined as a single suicide event. Relative risks of suicide were calculated by comparing groups defined by sex, ethnicity, NCAA division, and sport. Statistics were run in Microsoft Excel 2010. Significance was defined as a P value <0.05. The University of Washington Human Subjects Division approved this research study.

Results

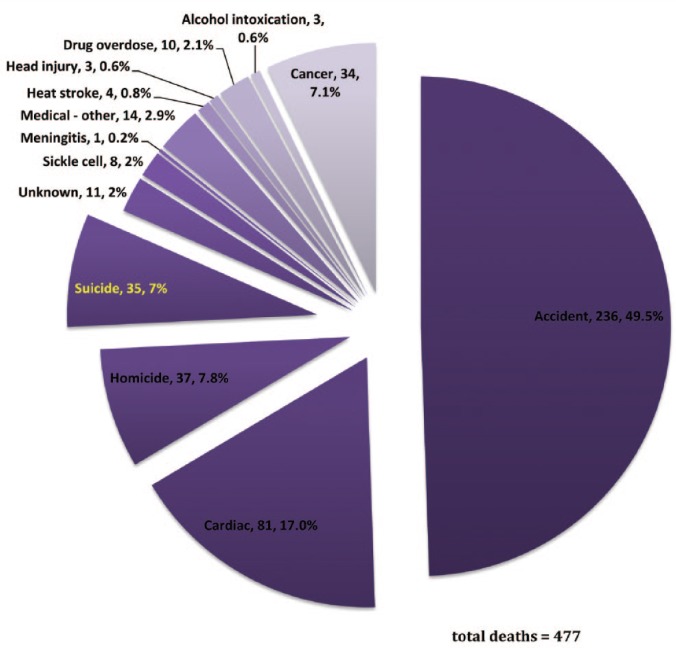

A total of 3,773,309 individual athlete participant seasons were reported during the 9-year study period (57.1% male athletes, 42.9% female athletes).23 The majority of athletes were white (72.9%), compared with African American (15.2%) and Hispanic (3.9%). A total of 477 student-athlete deaths were reported, with an overall mortality of 12.6/100,000 athletes per year. Thirty-five cases of suicide, including 6 cases of suspected suicide, were identified. Method of suicide was available for 15 of 35 (66.7%) cases, with 6 cases involving a self-inflicted gunshot wound, 3 cases of hanging, and 2 cases of a jump from elevation. Thirteen cases of drug or alcohol overdose were excluded as case details supported an accidental, rather than intentional, act. A cause of death was not identified in 11 cases. Suicide represented 7.3% (35/477) of all-cause mortality (Figure 1). The overall suicide rate was 0.93/100,000 student athletes per year. Suicide represented the fourth leading cause of death, following traumatic accidents, cardiovascular deaths, and homicide (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Etiology of death in National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) athletes, 2003-2004 to 2011-2012.

Age

The mean and median age of death was 20 years. Suicides occurred in all scholastic years, including 8 cases in freshman, 10 cases in sophomores, 5 cases in juniors, and 9 cases in seniors (3 cases with unknown scholastic year).

Sex

Twenty-nine cases of suicide occurred in male athletes, accounting for 82.9% of total cases, compared with 6 cases in female athletes (17.1%). The rate of suicide in male athletes was significantly higher compared with female athletes (1.34/100,000 vs 0.37/100,000), with a relative risk (RR) of 3.67 (P < 0.01; 95% CI, 1.51-8.76) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Incidence of suicide by sex

| Sex | n | % of Total Suicides | NCAA Participants | Death Rate (per 100,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 29 | 82.9 | 2,153,078 | 1.35 |

| Female | 6 | 17.1 | 1,620,174 | 0.37 |

NCAA, National Collegiate Athletic Association.

Race

Twenty-four cases occurred in white athletes (68.5% of total cases), compared with 7 cases (20%) in African American athletes and 4 cases in student athletes of other ethnic backgrounds (Table 2). The relative risk of suicide in African American athletes compared with white athletes was 1.4 (P = 0.45; 95% CI, 0.26-3.25).

Table 2.

Incidence of suicide by ethnicity

| Ethnicity | n | % of Total Suicides | NCAA Participants | Death Rate (per 100,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 24 | 68.5 | 2,752,594 | 0.87 |

| African American | 7 | 20.0 | 572,664 | 1.22 |

| Other | 4 | 11.5 | 447,994 | 0.89 |

NCAA, National Collegiate Athletic Association.

NCAA Division

Seventeen cases occurred in NCAA division I athletes, compared with 9 cases in Division II and 9 cases in Division III (Table 3). No statistically significant difference in suicide rates was identified between divisions (P = 0.08-0.12).

Table 3.

Incidence of suicide by NCAA division

| NCAA Division | n | % of Total Suicides | NCAA Participants | Death Rate (per 100,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 17 | 48.6 | 1,486,801 | 1.14 |

| II | 9 | 25.7 | 821,364 | 1.10 |

| III | 9 | 25.7 | 1,464,628 | 0.61 |

NCAA, National Collegiate Athletic Association.

Sport

The greatest number of cases was reported among football athletes (n = 13), followed by soccer (n = 5), track/cross-country (n = 5), baseball (n = 4), and swimming (n = 3). The highest incidence of suicide was identified in football athletes (2.25/100,000) (Table 4). Notably, football athletes had a relative risk of 2.21 of committing suicide compared with all other male, nonfootball athletes (P = 0.03; 95% CI, 1.07-4.61). When comparing suicide in football athletes to all other NCAA athletes regardless of sex, the relative risk of suicide is 3.27 (P < 0.01; 95% CI, 1.65-6.5). No other sport-to-sport or sport-to–overall participant comparisons of suicide met statistical significance.

Table 4.

Incidence of suicide by sport

| Sport | n | % of Total Suicides | NCAA Participants | Death Rate (per 100,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Football | 13 | 37.1 | 576,982 | 2.25 |

| Soccer | 5 | 14.3 | 395,494 | 1.26 |

| Track/cross-country | 5 | 14.3 | 418,069 | 1.20 |

| Baseball | 4 | 11.5 | 267,688 | 1.49 |

| Swimming | 3 | 8.6 | 178,849 | 1.68 |

| Other | 5 | 14.3 | 1,936,227 | 0.26 |

NCAA, National Collegiate Athletic Association.

Discussion

Suicide is an important and preventable cause of death among NCAA student athletes. This study suggests that suicide rates in NCAA student athletes are substantially lower than prior estimates in college students and individuals of collegiate age.4,19 In comparing our findings with the CDC census data for suicide, NCAA athletes have a relative risk of 0.08 (P <0.01; 95% CI, 0.06-0.11) of committing suicide compared with the general population of collegiate age. A suicide incidence of 1.2/100,000 was found for NCAA student athletes participating between 2004 and 2008.9 Similarly, an incidence of 0.8/100,000 suicides was found in a 10-year analysis of sudden death in college student athletes.13 This study provides additional information that is consistent with these prior reports and suggests that athletic participation may confer a protective effect against suicide.

The Durkeim theory of suicidality suggests that students are more tightly integrated into conventionally supportive social networks that buffer against psychological consequences of social isolation.7 This theory explains why suicide among college students is lower than in nonstudents of comparable age, implying that the social supports of the collegiate environment confer a protective effect against suicidal behaviors.15 Such an effect may be magnified for athletes, who are provided even greater opportunities to engage in structured social networks (ie, teams, regular activities with other athletes) that buffer against social isolation.

In contrast, factors such as injury and a failure to successfully compete or live up to self-expectations and the expectations of coaches, teammates, and family may lead to an increased risk of depression and suicidal behavior.2,8,20 Student athletes face unique pressures that involve balancing athletic participation with other aspects of collegiate life. Injury or inability to compete may not only interrupt their social structure but may also disrupt their own concepts of identity and self-worth. The social and psychological context at play for athletes is complicated and requires further study.

The increased relative risk of suicide in male athletes is comparable with data compiled by the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, in which male individuals of collegiate age were found to have a relative risk of 5.1 of committing suicide.4 Likewise, in a population of college students, the male suicide rate (9/100,000) was double that of female college students of the same age (4.5/100,000).19

African American NCAA athletes were noted to have a higher relative risk of suicide in this study than white athletes, though the difference did not meet statistical significance. This finding differs from reports in the general and collegiate population, in which whites have a higher rate of suicide. In a study of “Big 10” university students, as many as 87% of reported suicides occurred in white students.19 Similarly, the CDC reports that white, college-aged individuals have a relative risk of 1.6 compared with black individuals.4

NCAA football athletes demonstrated the highest incidence of suicide among all sports and a significantly higher risk of suicide than male athletes participating in other NCAA-sanctioned sports. Possible contributing factors to this finding include the violent nature of the sport, sociocultural and demographic differences among sports, increased pressure from participating in a high-profile sport, and an increased risk of injury and time lost to injury. Although football is also known to be a high-risk sport for concussion, this study is not able to determine a causative or correlative relationship, as concussion data were not available for the cases in this study. Ultimately, this finding deserves further investigation to clarify football-specific suicide risks and associations.

At this time, student-athlete mental health, athletic training, and sports medicine resources should work to identify and manage depression and suicidality among NCAA athletes, especially in higher risk groups. Physicians could consider validated outcome scales to assess health-related quality of life and mood disturbance in individuals presenting with injury or mental health concerns to improve detection of depression and suicidal behavior.

In considering models for supporting the mental health of NCAA student athletes, it is important to recognize existing educational and structured efforts of the NCAA and collegiate institutions to address this issue. The NCAA has published a Managing Student-Athletes’ Mental Health Issues handbook as a means of educating coaches and athletic personnel about mental health concerns in athletes.21 Many athletic departments have begun to develop structured plans and employ mental health professionals to address the well-being of their athletes.11 Mental health professionals may assist with active management of depression and acute stress reactions related to illness, injury, personal loss, or the transition to college life.

Suicide prevention interventions should be multimodal and evidence-based.12 A staged approach to managing depression and suicidal ideation in a student population through ecological prevention, proactive prevention, early intervention, treatment and crisis intervention, and relapse intervention has been suggested.6 This method presents a useful model as it attempts to approach mental health concerns at various stages of the depression cycle using a variety of resources. Education of health care providers, coaches, staff, and athletes may promote early identification of warning signs of depression and suicidality among student athletes. The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends that all adults be screened for depression, citing a 10% to 47% increase in detection and diagnosis.22 Given that more than 90% of individuals committing suicide are found to carry DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition)–categorized psychiatric illness,12 screening at key times during athletic participation may promote early identification of athletes at risk or with mental health disorders. Even though student athletes appear to have a lower risk of suicide compared with the general population, the increased contact that student athletes have with athletic trainers and team physicians may make it possible to prevent these tragedies with appropriate education on warning signs. Training medical staff to identify and manage mental health emergencies is an important concept that requires further development, given the variability of available mental health training. In particular, developing modules that deliver a standardized approach to the depressed or suicidal athlete may serve as a valuable addition to fellowship training.

Limitations

This study relies on a voluntary database of student-athlete deaths to which collegiate institutions contribute cases. The lack of a mandatory or more rigorous prospective monitoring system for suicide in the college athlete population may lead to unidentified or missed cases. Given the sensitive nature of suicide deaths, particularly in athletes who represent prominent members of their collegiate community, it is also possible that suicide cases go underreported. Furthermore, a reliance on media reports to obtain cases limits the acquisition of such details as method of suicide. Thus, the incidence of suicide in NCAA athletes found in this study should be considered a minimum estimate.

Conclusion

Suicide represents an important and preventable cause of death in the NCAA student-athlete population. Understanding the incidence of suicide in collegiate athletes provides a framework for resource allocation, development, and implementation of suicide prevention programs.

Footnotes

The following authors declared potential conflicts of interest: Ashwin L. Rao, MD, received payment for lectures, including service on speakers’ bureaus from AMSSM.

References

- 1. Armstrong SA, Oomen-Early J. Social connectedness, self-esteem, and depression symptomatology among collegiate athletes versus nonathletes. J Am Coll Health. 2009;57:521-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bovard RS. Risk behaviors in high school and college sport. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2008;7:359-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown DR, Blanton CJ. Physical activity, sports participation, and suicidal behavior among college students. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:1087-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fatal injury reports, national and regional, 1999-2013. http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate10_us.html. Accessed November 2014.

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leading causes of death reports, national and regional, 1999-2013. http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcaus10_us.html. Accessed November 2014.

- 6. Drum DJ, Denmark AB. Campus suicide prevention: bridging paradigms and forging partnerships. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2012;20:209-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Durkheim E. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. New York, NY: Free Press; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dvjorak RD, Lamis DA, Malone PS. Alcohol use, depressive symptoms, and impulsivity as risk factors for suicide proneness among college students. J Affect Disord. 2013;149:326-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harmon KG, Asif IM, Klossner D, Drezner JA. Incidence of sudden cardiac death in National Collegiate Athletic Association athletes. Circulation. 2011;123:1594-1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kokotailo PK, Henry BC, Koscik RE, Fleming MF, Landry GL. Substance use and other health risk behaviors in collegiate athletes. Clin J Sports Med. 1996;6:183-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kornspan AS, Duve MA. A nice and a need: a summary of the need for sports psychology consultants in collegiate sports. Ann Am Psychother Assoc. 2006;9:19-25. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies. A systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294:2064-2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maron BJ, Haas TS, Murphy CJ, Ahluwalia A, Rutten-Ramos S. Incidence and causes of sudden death in U.S. college athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1636-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McIntosh JL, Drapeau CW. U.S.A suicide 2011: official final data. http://www.suicidology.org/Portals/14/docs/Resources/FactSheets/2011OverallData.pdf. Accessed June 2014.

- 15. Miller KE, Hoffman JH. Mental well-being and sport-related identities in college students. Sociol Sport J. 2009;26:335-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nattiv A, Puffer J. Lifestyle and health risks of collegiate athletes. J Fam Pract. 1991;33:585-590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neal TL, Diamond AB, Goldman S, et al. Inter-association recommendations for developing a plan to recognize and refer student-athletes with psychological concerns at the collegiate level: an executive summary of a consensus statement. J Athl Train. 2013;48:716-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Oler MJ, Mainous AG, 3rd, Martin CA, et al. Depression, suicidal ideation, and substance abuse among adolescents: are athletes at less risk? Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:781-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Silverman MM, Meyer PM, Sloane F, Raffel M, Pratt DM. The Big Ten Student Suicide Study: a 10-year study of suicides on Midwestern university campuses. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1997;27:285-303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith AM, Milliner EK. Injured athletes and the risk of suicide. J Athl Train. 1994;29:337-341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thompson RA, Sherman RA. Managing Student-Athletes’ Mental Health Issues. Indianapolis, IN: National Collegiate Athletic Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:784-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zgon E. NCAA Student Athlete Ethnicity Report. Indianapolis, IN: National Collegiate Athletic Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]