Abstract

Context:

There is increased growth in sports participation across the globe. Sports specialization patterns, which include year-round training, participation on multiple teams of the same sport, and focused participation in a single sport at a young age, are at high levels. The need for this type of early specialized training in young athletes is currently under debate.

Evidence Acquisition:

Nonsystematic review.

Study Design:

Clinical review.

Level of Evidence:

Level 4.

Conclusion:

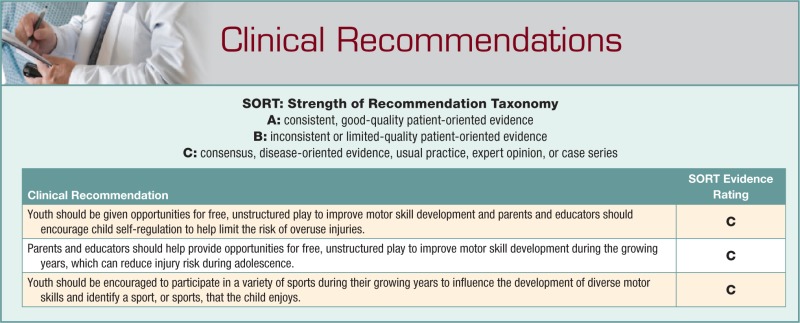

Sports specialization is defined as year-round training (greater than 8 months per year), choosing a single main sport, and/or quitting all other sports to focus on 1 sport. Specialized training in young athletes has risks of injury and burnout, while the degree of specialization is positively correlated with increased serious overuse injury risk. Risk factors for injury in young athletes who specialize in a single sport include year-round single-sport training, participation in more competition, decreased age-appropriate play, and involvement in individual sports that require the early development of technical skills. Adults involved in instruction of youth sports may also put young athletes at risk for injury by encouraging increased intensity in organized practices and competition rather than self-directed unstructured free play.

Strength-of-Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT):

C.

Keywords: injury prevention, youth sports, athletic performance, neuromuscular training

Early sport specialization appears to be increasing in young athletes,21,23 and the pressure to select 1 sport to the exclusion of others is believed to come from coaches, parents, and other youth athletes.27 There is concern that engaging in year-round intense training programs in a single sport at an early age may result in negative outcomes for some young athletes, such as overuse injuries, burnout, and dropping out of sport(s).2,17 This clinical review aims to synthesize the current evidence to outline the potential negative outcomes related to sports specialization in young athletes and to guide alternative strategies that optimize enjoyment and safety of youth sports.29

Sports Specialization Risks and Etiologies

Definition and Volume Risk

Sports specialization can be defined as “intensive year-round training in a single sport at the exclusion of other sports.”39 This definition allows for a spectrum of sports specialization where a highly specialized athlete may be able to (1) choose a main sport, (2) participate for greater than 8 months per year in 1 main sport, and (3) quit all other sports to focus on 1 sport.40 Thus, the degree of sports specialization can be defined as low, moderate, or high based on the number of definition components to which a young athlete may respond in a positive way.40 Historically, it has been difficult to separate the known risks of intensive training based on high weekly volumes of training from the independent risks of sports specialization in overuse injuries. More recently, it has been shown that high training volume carries its own risks for injury, and that increased exposure has a linear relationship to adjusted injury risk in high school athletes.38,45,60 Specifically, exceeding 16 hours per week of total sports participation, regardless of the number of sports, seems to carry the greatest risk38,45,60; however, age-adjusted recommendations for volume risk have not been made for many sports. Nearly two-thirds of middle school–aged children receiving medical treatment sustained an injury during sports or physical activity, but the training and rates of specialization were not included.57 Additionally, athletes who participate in more competitive levels or higher volumes of training have an increased incidence of injury.20,48,60 For example, adolescent baseball pitchers are at significant risk (4-36 times) of sustaining an injury due to overuse and fatigue.53 Until recently, these injury risks were not correlated with sports specialization in young athletes.

Independent Risks of Sports Specialization

One study of 1190 young athletes, 7 to 18 years old, compared training patterns of injured athletes at sports medicine clinics versus uninjured athletes during a sports preparticipation exam.40 Those athletes who met the definition of a highly specialized athlete had 2.25 (range, 1.27-3.99) greater odds of having sustained a serious overuse injury than an unspecialized young athlete, even when accounting for hours per week sports exposure and age. In fact, there was a continuum, with the more specialized an athlete (per the 3 criteria proposed earlier) the greater this risk of injury (Table 1). A separate retrospective study of 546 high school athletes found a relationship between the development of patellofemoral pain syndrome and single-sport training in athletes in basketball, soccer, and volleyball.35 Exposures were estimated by seasons rather than by weekly hours of participation. Patellofemoral pain was one of the most common diagnoses in the study of 1190 athletes discussed earlier,40 and this corroborates the findings that sports-specialized training is an independent risk factor for injury in young athletes.

Table 1.

Degree of sports specialization and risk of all-cause injuriesa

| Degree of Specialization | Risk of Injury | Risk of Serious Overuse Injury | Risk of Acute Injury |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low specialization (0 or 1 of the following): Year-round training (>8 months per year) Chooses a single main sport Quit all sports to focus on 1 sport |

Low | Low | Moderate |

| Moderately specialized (2 of the following): Year-round training (>8 months per year) Chooses a single main sport Quit all sports to focus on 1 sport |

Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| Highly specialized (3/3 of the following): Year round training (>8 months per year) Chooses a single main sport Quit all sports to focus on 1 sport |

High | High | Low |

Reproduced with permission from Jayanthi et al.40

Age-Related Play and Eligibility Rules

Age-adjusted training and competition volumes have not been well studied in many youth sports. Nonetheless, youth sports leagues have instituted rules designed to prevent injury and promote age-appropriate levels of competition.47,54 USA youth baseball has tried to utilize evidence for youth baseball leagues to guide age-adjusted pitch counts.47 Unfortunately, there are data to suggest that these guidelines are not followed by many coaches, with the majority reporting additional pitching instruction or camps.24 In addition, pitch count may be difficult to monitor when pitchers participate on multiple teams over the course of a tournament or season. At present, there is no effective model to develop appropriate age-related recommendations. In response to early burnout and premature retirements in young professional tennis players, the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) developed an age eligibility rule (AER). At 10-year follow-up, this was effective in increasing career lengths by about 2 years (43%) and reducing premature sports dropout from 7% to 1% in young professional women’s tennis players.54 The key component to this AER was a “phased in” approach to the number of tournaments allowed, beginning no earlier than the age of 14 years, with annual age-related increases until 18 years as well as numerous player development programs. In a separate study, a training rule based on age (age vs hours) recently demonstrated increased risk of injury and serious overuse injury if a young athlete participated in more weekly organized sports hours than their age.40 Potentially, volume recommendations for training and competition should be age or developmentally adjusted across all sports, and these rules may provide a model for other sports.

What Makes Sports Specialization a Risk Versus Diversified Sports Experience?

The lack of diversified activity may not allow young athletes to develop the appropriate neuromuscular skills that are effective in injury prevention and does not allow for the necessary rest from repetitive use of the same segments in the body. The positive transfer of skill with diversification is important in the successful development of a young athlete.15,28 Until recently, we did not have enough evidence to support the concept of sports specialization as an independent risk factor for injury, apart from exposure or the combination of high volume and intensity; however, the following theories may provide some additional rationale for these risks.

Specialized Athletes Are More Likely to Have Year-Round Exposure to a Single Sport

Year-round exposure to a single sport may be one of the primary reasons for injury risk in specialized athletes. In youth baseball pitchers, there was a greater risk for shoulder and elbow surgery in those that pitched greater than 8 months per year and in those that pitched regularly with arm pain or fatigue.53 Another study of high school athletes found that athletes who did not take at least 1 sport season off during the year (eg, fall, winter, spring, or summer) were more likely to sustain an injury independent of whether the athlete was characterized as a single or multisport athlete.45 However, the lack of difference in risks between the 2 groups may be due to the fact that the weekly exposure hours were not monitored. Thus, it makes it more difficult to draw firm conclusions with regard to the risk of injury when exposure is already reduced. The risk of injury or medical withdrawal was not demonstrated in a population of 519 Midwest junior tennis players when using a similar model.38 This might be due to the very high rates of year-round training (93.4% at >9 months per year) that limited the ability for a comparison with a control group.38 Regardless, there seems to be emerging data that indicate increased risk of injury with year-round training—a key component of specialized training.

Repetitive Technical Skills and High-Risk Mechanics

Highly specialized athletes who perform at an elite level commonly participate in individual and technical sports. For example, the majority of junior elite tennis players (70%) specialized at a mean age of 10.4 years old, while 95% were specialized by the age of 18 years.38 Other individual, technical sports such as gymnastics, dance, swimming, and diving typically require early specialization and high intense volumes in prepubescent stages. While speculative, historical trends indicate that athletes in team sports appear more likely to diversify their sports, but even this trend has started to change. Certain positions in team sports, such as a baseball pitcher, can be trained as a specialized individual sport athlete. There is a paucity of information on the biomechanical risks of sports for overuse injury in young athletes, but some examples support the potential for injury risk development in certain sports based on mechanics and training. Specific to tennis, the mean age for the introduction of the kick serve (a heavy topspin serve that typically requires significant lumbar hyperextension and extreme abduction and external rotation of the shoulder) to adolescent athletes was approximately 13 years old.42 Associated with this was a relatively high rate of shoulder and elbow injuries.42 Similarly, increased forces to the back and shoulder in elite tennis players, but not in junior players, have been related to the kick serve technique, and the mechanics of this serve may put more stress on the adolescent body and thus increase injury risk.1,61 Baseball pitchers are much more likely to have overuse elbow injuries related to pitching volume, pitching fatigue, and poor mechanics that result in increased elbow torque and forces.25 Likewise, young gymnasts often have wrist pain that is related to the volume of training intensity and skill level, likely related to repetitive impact forces in wrist dorsiflexion during growth periods.18,19

Overscheduling and Competition

The competitive demands are also typically higher for a specialized athlete given the pressure for successful performance during games, matches, meets, or tournaments. In most sports, risk of injury is expected to be higher during competition compared with training.36 These data have been consistently demonstrated in a variety of National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) sports. There are a few sports such as gymnastics and figure skating where the intense and voluminous (7 days a week) specialized technical training may far exceed the exposure of a short competitive program in a meet. Also, the level of specialized participation may involve higher level competition (particularly at younger ages), which again may be a risk factor for injury. Scheduled intense competitions that can last 6 hours or longer without adequate rest and recovery have been implicated as a risk factor for potential injury as well.13,38 Suggested minimal rest periods between repeated bouts of same-day competition have been proposed,11,38 as well as limiting training 48 hours prior to competition to help reduce injury risk.46 However, more research is needed to understand the risk factors associated with overscheduling competition and to establish formal guidelines to optimize youth sport performance.

Psychological Burnout

There are increased pressures in intense, adult-driven specialized training and competitions. The psychological risk of burnout, depression, and increased risk of injury may be a reason for withdrawal from sport in young athletes who took part in early specialized training. Talent development research on young athletes demonstrates that professionalized, adult-style practices are likely not optimal for fostering talent development.16 Specifically, research has indicated that adolescents need to enjoy the activities of their domain, and that intrinsic motivators are key to maintaining participation and goal achievement.16 Unfortunately, this is often not the case as the temptation of collegiate scholarships and stardom causes thousands of adolescent athletes to specialize in single sports and, subsequently, train year-round in sport-specific skills. While this has resulted in more highly skilled, sport-mature athletes at a younger age, it is isolating the child and has the potential to lead to increased stress and pressure and an overall feeling that the child lacks control or decision-making power over their lives.68 It is important to understand the implications of sport specialization at all levels of competition to better manage athletes in a way that is in their best interest to prevent burnout. In one such study on burnout, earlier specialization in swimming resulted in less time on the national team and earlier retirement compared with later specialization.10 There is also a valid concern of sports attrition related to early, specialized intense training. In ice hockey, players more prone to dropout began off-ice training at a younger age, while they also invested a larger number of hours in off-ice training at a younger age compared with those who continued participation.66 Other studies in sports such as swimming and tennis suggest that retirement from sport may be the consequence of burnout, which young athletes may experience with continued intense and specialized participation.33,66

Burnout likely results from a combination of physical and psychological factors. For example, a study of junior tennis players indicated that the burned-out players had less input into training and sport-related decisions and practiced fewer days with decreased motivation compared with the players who did not exhibit similar levels of burnout.31-33 This resulted in athletes who were more withdrawn and less psychologically prepared to cope with the high stress realities of their sport.31-33 Moreover, while a lack of fun is a more frequent reason for withdrawal from sport at earlier ages, performance pressure seems to become more central to withdrawal as athletes get older.14,30 Positive peer relationships also increase enjoyment and sport commitment in youth. However, if there was a point that the child felt that the sport conflicted with outside social development, both their commitment to and motivation for that sport decreased.56 Similarly, sport participation of a child’s best friend was a strong predictor of adolescent sport commitment and involvement3,67; however, playing at a higher performance level outside of the child’s age-specific peer group was linked to burnout in elite youth athletes.32,33 The potential interaction between burnout, overtraining, and risk of injury has been suggested as well.13 Young specialized athletes may be at risk for either, and the specialization may magnify these potential injury risk factors, which can create a cycle of recurrent injury. Based on the current evidence, it may be best to limit intense specialized training to less than 16 hours per week, and instructors should employ strategies to prevent overscheduling (eg, scheduled rest periods) and should monitor signs of burnout or fear of reinjury. Improved communication between those in management of youth sports participation (coaches and parents) can help limit the potential risks of specialized athletes.

Primary Injury and Effects of Fear of Reinjury

While many athletes will recover after an injury,59 injuries that occur during sports or physical activity may deter some athletes from further participation. One year or more after an injury or surgery, approximately 65% of athletes returned to their previous level of sporting activities, despite functional recovery from the injury.7,8,26,49 Twenty percent of elite athletes have reported injury as a reason for quitting their sport,14 and up to 8% of adolescents drop out of sporting activities due to injury or fear of injury.34 Many athletes within 12 months of an injury report lower levels of physical and mental health,5 with a significant reduction in their physical activity.4 This reduction in physical activity can have negative health consequences,9,22,63 and insufficient physical activity is one of the top 5 reasons for global deaths from noncommunicable diseases.50 This pattern of physical inactivity can persist into adolescence and adulthood.12,37,51,52

Psychological readiness to return to sport after an injury does not always correspond with physical readiness.58 Fear of reinjury is a frequently cited reason athletes do not return to sport or reduce their level of physical activity.6,41,43,44,62 Fear of injury is associated with pain-related anxiety and self-reported and behavioral impairments in patients with chronic low back pain.65 Higher levels of pain and pain catastrophizing after injury to the shoulder is associated with fear of reinjury/movement.55 A large meta-analysis found a strong, positive association with pain-related fear and disability.69 The cumulative effects of fear of reinjury in the specialized sport, with the lack of diversified exposure to a variety of sports, may limit a child from successfully reintegrating into any form of sporting activity.

Young specialized athletes who exhibit characteristics of fear of reinjury may need strategies and techniques to adequately address these issues if they aim to return directly back to the same sport in which they were injured. In addition, some specialized athletes may have low personal coping skills to deal with psychological aspects of the injury.64 Educating the athlete and identifying inaccurate information about the injury and rehabilitation process may reduce the emotional stress associated with the injury. This may include adequately counseling the athlete about the recovery process and the challenges of rehabilitation. Effective strategies to help young athletes combat fear of reinjury may enhance their ability to successfully return to sports and continue life-long activity participation.

Conclusion

The emerging evidence indicates that intense, year-round training specialized to a single sport can be a risk factor for various issues, and parents and coaches need to be cautious about encouraging early sport specialization in youth. Three components that define early sports specialization include year-round training (>8 months per year), choosing a single main sport, and quitting all other sports to focus on 1 sport. Increased degree of specialization is positively correlated with increased serious overuse injury risk. Some of the current literature regarding the relationship between sport specialization and injury (ie, association does not equal causation) could simply be a marker for excessive training volume in youth. The volume of training defined by hours per week of organized sports can increase injury risk either by exceeding 16 hours per week of organized sports or hours per week of organized sports greater than the athlete’s age. Specialized young athletes may be at increased risk for injury since they may be more likely to participate in year-round training and may be involved in individual sports that require the early development of technical skills. Adults involved in instruction of youth sports should be vigilant about noting any signs of stress, burnout, and physical symptoms in these athletes and be prepared to take corrective action such as backing off training intensity and frequency.

Footnotes

The following author declared potential conflicts of interest: Neeru Jayanthi, MD, is a paid consultant for American Academy of Pediatrics and the Woman’s Tennis Association Tour.

References

- 1. Abrams GD, Renstrom PA, Safran MR. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal injury in the tennis player. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:492-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Academy of Pediatrics. Intensive training and sports specialization in young athletes. Pediatrics. 2000;106:154-157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anderssen N, Wold B. Parental and peer influences on leisure-time physical activity in young adolescents. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1992;63:341-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andrew N, Wolfe R, Cameron P, et al. The impact of sport and active recreation injuries on physical activity levels at 12 months post-injury. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24:377-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Andrew NE, Wolfe R, Cameron P, et al. Return to pre-injury health status and function 12 months after hospitalisation for sport and active recreation related orthopaedic injury. Inj Prev. 2012;18:377-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE. Fear of re-injury in people who have returned to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. J Sci Med Sport. 2012;15:488-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ardern CL, Webster KE, Taylor NF, Feller JA. Return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the state of play. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:596-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ardern CL, Webster KE, Taylor NF, Feller JA. Return to the preinjury level of competitive sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: two-thirds of patients have not returned by 12 months after surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:538-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barnett LM, van Beurden E, Morgan PJ, Brooks LO, Beard JR. Childhood motor skill proficiency as a predictor of adolescent physical activity. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:252-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barynina I, Vaitsekhovskii S. The aftermath of early sports specialization for highly qualified swimmers. Fitness Sports Rev Int. 1992;27:132-133. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bergeron MF, Laird MD, Marinik EL, Brenner JS, Waller JL. Repeated-bout exercise in the heat in young athletes: physiological strain and perceptual responses. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:476-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Biddle SJ, Pearson N, Ross GM, Braithwaite R. Tracking of sedentary behaviours of young people: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2010;51:345-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brenner JS. Overuse injuries, overtraining, and burnout in child and adolescent athletes. Pediatrics. 2007;119:1242-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Butcher J, Lindner KJ, Johns DP. Withdrawal from competitive youth sport: a retrospective ten-year study. J Sports Behav. 2002;25:145-163. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Côté J, Lidor R, Hackfort D. SSP position stand: to sample or to specialize? Seven postulates about youth sport activities that lead to continued participation and elite performance. Int J Sport Exercise Psychol. 2009;7:7-17. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Csikszentmihalyi M, Rathunde KR, Whalen S. Talented Teenagers: The Roots of Success and Failure. 1st ed Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17. DiFiori JP, Benjamin HJ, Brenner JS, et al. Overuse injuries and burnout in youth sports: a position statement from the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:287-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DiFiori JP, Puffer JC, Aish B, Dorey F. Wrist pain in young gymnasts: frequency and effects upon training over 1 year. Clin J Sport Med. 2002;12:348-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. DiFiori JP, Puffer JC, Mandelbaum BR, Mar S. Factors associated with wrist pain in the young gymnast. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:9-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Emery CA. Risk factors for injury in child and adolescent sport: a systematic review of the literature. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13:256-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Epstein D. Sports should be child’s play. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/11/opinion/sports-should-be-childs-play.html?_r=2. Accessed July 19, 2014.

- 22. Faigenbaum AD, Myer GD. Exercise deficit disorder in youth: play now or pay later. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11:196-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Farrey T. Game On: The All-American Race to Make Champions of Our Children. Bristol, Connecticut: ESPN Books; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fazarale JJ, Magnussen RA, Pedroza AD, Kaeding CC. Knowledge of and compliance with pitch count recommendations: a survey of youth baseball coaches. Sports Health. 2012;4:202-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fleisig GS, Weber A, Hassell N, Andrews JR. Prevention of elbow injuries in youth baseball pitchers. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2009;8:250-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gobbi A, Francisco R. Factors affecting return to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with patellar tendon and hamstring graft: a prospective clinical investigation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:1021-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gould D. The professionalization of youth sports: it’s time to act! Clin J Sport Med. 2009;19:81-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gould D, Carson S. Fun & games? Myths surrounding the role of youth sports in developing Olympic champions. Youth Stud Aust. 2004;23:19. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gould D, Carson S, Fifer A, Lauer L, Benham R. Social-emotional and life skill development issues characterizing today’s high school sport experience. J Coach Educ. 2009;2:1-25. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gould D, Feltz D, Horn T, Weiss MR. Reasons for attrition in competitive youth swimming. J Sport Behav. 1982;5:155-165. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gould D, Tuffey S, Udry E, Loehr JE. Burnout in competitive junior tennis players: III. Individual differences in the burnout experience. Sport Psychol. 1997;11:257-276. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gould D, Tuffey S, Udry E, Loehr JE. Burnout in competitive junior tennis players: II. Qualitative analysis. Sport Psychol. 1996;10:341-366. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gould D, Udry E, Tuffey S, Loehr JE. Burnout in competitive junior tennis players: I. A quantitative psychological assessment. Sport Psychol. 1996;10:322-340. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Grimmer KA, Jones D, Williams J. Prevalence of adolescent injury from recreational exercise: an Australian perspective. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27:266-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hall R, Barber Foss K, Hewett TE, Myer GD. Sport specialization’s association with an increased risk of developing anterior knee pain in adolescent female athletes. J Sport Rehabil. 2015;24:31-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hootman JM, Dick R, Agel J. Epidemiology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports: summary and recommendations for injury prevention initiatives. J Athl Train. 2007;42:311-319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Janz KF, Dawson JD, Mahoney LT. Tracking physical fitness and physical activity from childhood to adolescence: the Muscatine study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:1250-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jayanthi N, Dechert A, Durazo R, Dugas L, Luke A. Training and sports specialization risks in junior elite tennis players. J Med Sci Tennis. 2011;16:14-20. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jayanthi N, Pinkham C, Dugas L, Patrick B, Labella C. Sports specialization in young athletes: evidence-based recommendations. Sports Health. 2013;5:251-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jayanthi NA, LaBella CR, Fischer D, Pasulka J, Dugas LR. Sports-specialized intensive training and the risk of injury in young athletes: a clinical case-control study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:794-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kontos AP, Feltz DL, Malina RM. The perception of risk of injury in sports scale: confirming adolescent athletes’ concerns about injury. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2000;22:S12. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kovacs M, Ellenbecker T. An 8-stage model for evaluating the tennis serve implications for performance enhancement and injury prevention. Sports Health. 2011;3:504-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kvist J, Ek A, Sporrstedt K, Good L. Fear of re-injury: a hindrance for returning to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2005;13:393-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Langford JL, Webster KE, Feller JA. A prospective longitudinal study to assess psychological changes following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:377-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Loud KJ, Gordon CM, Micheli LJ, Field AE. Correlates of stress fractures among preadolescent and adolescent girls. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e399-e406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Luke A, Lazaro RM, Bergeron MF, et al. Sports-related injuries in youth athletes: is overscheduling a risk factor? Clin J Sport Med. 2011;21:307-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lyman S, Fleisig GS, Waterbor JW, et al. Longitudinal study of elbow and shoulder pain in youth baseball pitchers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:1803-1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Maffulli N, Baxter-Jones AD, Grieve A. Long term sport involvement and sport injury rate in elite young athletes. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:525-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mithoefer K, Williams RJ, 3rd, Warren RF, Wickiewicz TL, Marx RG. High-impact athletics after knee articular cartilage repair: a prospective evaluation of the microfracture technique. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1413-1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mountjoy M, Andersen LB, Armstrong N, et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement on the health and fitness of young people through physical activity and sport. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:839-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Ford KR, Best TM, Bergeron MF, Hewett TE. When to initiate integrative neuromuscular training to reduce sports-related injuries and enhance health in youth? Curr Sports Med Rep. 2011;10:155-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nader PR, Bradley RH, Houts RM, McRitchie SL, O’Brien M. Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity from ages 9 to 15 years. JAMA. 2008;300:295-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Olsen SJ, Fleisig GS, Dun S, Loftice J, Andrews JR. Risk factors for shoulder and elbow injuries in adolescent baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:905-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Otis C, Crespo M, Flygare C, et al. The Sony Ericsson WTA Tour 10 year age eligibility and professional development review. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:464-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Parr J, Borsa P, Fillingim R, et al. Psychological influences predict recovery following exercise induced shoulder pain. Int J Sports Med. 2014;35:232-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Patrick H, Ryan AM, Alfeld-Liro C, Fredricks JA, Hruda LZ, Eccles JS. Adolescents’ commitment to developing talent: the role of peers in continuing motivation for sports and the arts. J Youth Adolesc. 1999;28:741-763. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pickett W. Injuries. In: Boyce W, ed. Young People in Canada: Their Health and Well-Being. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Health Canada; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Podlog L, Eklund RC. The psychosocial aspects of a return to sport following serious injury: a review of the literature from a self-determination perspective. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2007;8:535-566. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Polinder S, Meerding WJ, Toet H, Mulder S, Essink-Bot ML, van Beeck EF. Prevalence and prognostic factors of disability after childhood injury. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e810-e817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rose MS, Emery CA, Meeuwisse WH. Sociodemographic predictors of sport injury in adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:444-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sheets AL, Abrams GD, Corazza S, Safran MR, Andriacchi TP. Kinematics differences between the flat, kick, and slice serves measured using a markerless motion capture method. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39:3011-3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shuer ML, Dietrich MS. Psychological effects of chronic injury in elite athletes. West J Med. 1997;166:104-109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Stodden DJ, Goodway S, Langendorfer S, Robertson M, Rudisill M, Garcia C. A developmental perspective on the role of motor skill competence in physical activity: an emergent relationship. Quest. 2008;60:290-306. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Team Physician Consensus Statement. Psychological issues related to injury in athletes and the team physician: a consensus statement. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:2030-2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Thibodeau MA, Fetzner MG, Carleton RN, Kachur SS, Asmundson GJ. Fear of injury predicts self-reported and behavioral impairment in patients with chronic low back pain. J Pain. 2013;14:172-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wall M, Côté J. Developmental activities that lead to dropout and investment in sport. Phys Educ Sport Pedagogy. 2007;12:77-87. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Weiss WM, Weiss MR. Sport commitment among competitive female gymnasts: a developmental perspective. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2007;78:90-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wolff A. High school sports: inside the changing world of our young athletes. Sports Illustrated. 2002;97(20):74-92. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zale EL, Lange KL, Fields SA, Ditre JW. The relation between pain-related fear and disability: a meta-analysis. J Pain. 2013;14:1019-1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]