Abstract

D-cycloserine (DCS) has been shown to enhance memory and, in a previous trial, once-weekly DCS improved negative symptoms in schizophrenia subjects. We hypothesized that DCS combined with a cognitive remediation (CR) program would improve memory of a practiced auditory discrimination task and that gains would generalize to performance on unpracticed cognitive tasks. Stable, medicated adult schizophrenia outpatients participated in the Brain Fitness CR program 3–5 times per week for 8 weeks. Subjects were randomly assigned to once-weekly adjunctive treatment with DCS (50 mg) or placebo administered before the first session each week. Primary outcomes were performance on an auditory discrimination task, the MATRICS cognitive battery composite score and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) total score. 36 subjects received study drug and 32 completed the trial (average number of CR sessions = 26.1). Performance on the practiced auditory discrimination task significantly improved in the DCS group compared to the placebo group. DCS was also associated with significantly greater negative symptom improvement for subjects symptomatic at baseline (SANS score ≥20). However, improvement on the MATRICS battery was observed only in the placebo group. Considered with previous results, these findings suggest that DCS augments CR and alleviates negative symptoms in schizophrenia patients. However, further work is needed to evaluate whether CR gains achieved with DCS can generalize to other unpracticed cognitive tasks.

Keywords: D-cycloserine, cognitive remediation, schizophrenia, MATRICS, SANS, memory

1. Introduction

Efforts to develop pharmacologic treatments for cognitive deficits and negative symptoms of schizophrenia over the past decade have proven mostly disappointing (Goff et al., 2011). This lack of success may reflect several problems, including heterogeneity of the illness and the inadequacy of current disease models for drug development. If cognitive deficits and negative symptoms result from aberrant neurodevelopment involving structural defects in synaptic function and connectivity, traditional pharmacologic models are unlikely to ameliorate symptoms. An alternative approach aims to enhance neuroplasticity by exploiting the brain’s inherent capacity to modify function in response to environmental demand, a process that appears to be impaired in schizophrenia (Daskalakis et al., 2008). Cognitive remediation (CR) is an example of this strategy, employing cognitive exercises to optimize efficiency of compromised brain circuits. In a carefully controlled trial, a CR program emphasizing auditory discrimination exercises was found to improve a broad range of cognitive functions in schizophrenia subjects (Fisher et al., 2009); similar findings have been reported with other CR approaches, although effect sizes have been small to moderate (Wykes et al., 2011). It remains unclear, however, whether the benefits of CR extend to cognitive domains that are not practiced and whether the cognitive gains translate into improved functioning if not combined with psychosocial interventions (Dickinson et al., 2010; Hooker et al., 2012; Murthy et al., 2012).

Neuroplasticity involves a series of biochemical steps often beginning with activation of glutamatergic N-methyl D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs). Stimulating NMDARs induces calcium entry, protein kinase activation, gene expression and protein synthesis (Kandel, 2001). Protein synthesis is required for long-lasting forms of synaptic plasticity (e.g. long-term potentiation or LTP) and long-term memory (LTM). Many forms of learning and memory depend on NMDARs including auditory discrimination conditioning (Dix et al., 2010; Dunn and Killcross, 2006; Tan et al., 1989).

As a strategy to enhance neuroplasticity and thereby optimize functioning of compromised brain circuits in schizophrenia, we have studied intermittent treatment with the NMDAR agonist, D-cycloserine (DCS). Although DCS may affect multiple NMDA receptor subtypes, it has greater efficacy at receptors containing the NR2C subunit compared to endogenous agonists D-serine and glycine (Dravid et al., 2010). NR2C-containing NMDARs are important for memory (e.g. Hillman et al., 2011) and show reduced expression in prefrontal cortex (PFC) of schizophrenia patients (Weickert et al., 2013; Beneyto and Meador-Woodruff, 2008). DCS has been shown to enhance LTP and improve LTM in rodents after a single dose (Walker et al., 2002; Watanabe et al., 1992), however, tolerance develops with repeated dosing (Parnas et al., 2005; Quartermain et al., 1994). DCS also improves auditory discrimination performance in rodents (Thompson and Disterhoft, 1997). Consistent with D-cycloserine’s memory effects being mediated by activity at NR2C-containing NMDARs, CIQ, a more selective potentiator of NR2C/2D-containing NMDARs, enhances retention of fear conditioning and extinction learning in rats and reverses MK801-induced deficits in prepulse inhibition and working memory (Ogden et al., 2013; Suryavanshi et al., 2013).

Schizophrenia patients exhibit memory impairments in tasks known to be sensitive to DCS facilitation. For instance, cortical neuroplasticity associated with motor training is impaired in schizophrenia (Daskalakis et al., 2008), and similar neuroplasticity is enhanced by DCS in healthy subjects (Nitsche et al., 2004). We have found deficits in fear extinction in subjects with schizophrenia (Holt et al., 2009; Holt et al., 2012), and numerous studies have demonstrated facilitation of fear extinction with DCS (Davis, 2011). We also found that a single dose of DCS selectively improved LTM in schizophrenia patients as measured by 7-day thematic recall on the Logical Memory Test (Goff et al., 2008).

We hypothesized that once-weekly DCS in schizophrenia patients would augment neuroplasticity induced by an 8-week “Brain Fitness” CR program, which emphasized auditory discrimination exercises. We further hypothesized that gains observed with the practiced task would generalize to other cognitive domains measured by the MATRICS battery. In addition, our design allowed us to attempt a replication of our prior finding that once-weekly DCS improves negative symptoms as measured by the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (Goff et al., 2008).

2. Materials and Methods

The study was registered as clinical trial NCT00963924 and received approval from the Partners Healthcare institutional review board. Subjects were adult outpatients, ages 18–65, recruited by advertisement and clinician referral at an urban community mental health center, with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, depressed type, and treated with a stable dose of any antipsychotic other than clozapine for at least 4 weeks. Patients were excluded from participation for significant medical illness, renal insufficiency, seizure disorder, substance abuse, pregnancy or nursing, or inability to perform the cognitive remediation program or cognitive battery. After the study was explained to them, subjects provided written consent to participate and were assessed by a research psychiatrist to confirm the diagnosis based on interview, review of records and consultation with treating clinicians. The research psychiatrist also completed a medical history and review of medical records to identify unstable medical illness.

Subjects were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to DCS (50 mg) or placebo prepared in identical capsules administered once weekly for 8 weeks, 60 minutes prior to training. The DCS dose was based on a single-blind dose finding trial conducted in schizophrenia subjects in which 50 mg produced improvement in working memory and negative symptoms whereas neither 15 mg or 250 mg were effective (Goff et al. 1995). A DCS dose of 50 mg has subsequently been demonstrated to improve negative symptoms and memory consolidation in schizophrenia subjects (Goff et al. 1999; Goff et al. 2008) and doses ranging from 50 to 500 mg improved response to CBT in individuals with anxiety disorders (Ressler et al. 2004; Norberg et al. 2008). In contrast, a DCS dose of 250 mg has been associated with worsening of psychosis in schizophrenia subjects (Cascella et al. 1994). The study biostatistician provided a computer-generated randomization sequence using the permuted block method stratified according to whether subjects enrolled in CR 3 or 5 times weekly. All study personnel were kept blind to treatment assignment except for the research pharmacist. The study, which was initiated in August, 2009, was designed to include 64 evaluable subjects in order to achieve 80% power to detect an effect size of 0.72, but was terminated in November, 2011, for administrative reasons (departure of the principal investigator) after 54 subjects were enrolled. Subjects were allowed to choose a frequency of 3 or 5 sessions per week for their participation in CR sessions during the 8 week trial. Subjects performed the Brain Fitness Program (Posit Science, San Francisco, CA) exercises in a specialized laboratory free of environmental distraction and were monitored by a technician. At the first session, subjects viewed a 20 minute overview developed by the manufacturer which outlined the program and provided instructions. They then completed a baseline measure of auditory discrimination (also provided by the manufacturer) which set the level of difficulty for the first CR session. Study drug was administered one hour prior to the first CR session each week. Subjects could complete a maximum of 40 one-hour sessions during which they were presented with three (of five possible) different cognitive exercises in addition to the auditory discrimination training. Each exercise lasted 15 minutes.

The following assessments were completed at baseline: Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale (PANSS), Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS), Global Assessment Scale (GAS), Heinreich Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (QoL), the Systematic Assessment for Treatment-Emergent Side Effects (SAFTEE), the MATRICS cognitive battery, and the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS, modified by removing the attention subscale). Subjects were queried for side effects at every visit. The clinical rating scales were repeated at weeks 4 and 8, the auditory discrimination measure was repeated at weeks 1, 2, 4, and 8, and the MATRICS battery was repeated at week 8 – all prior to drug administration.

The auditory discrimination task, described in detail elsewhere (Fisher et al., 2009; Keefe et al., 2012), involved trials in which the subject differentiated between rapidly-presented frequency-modulated sweeps separated by a short interstimulus interval (ISI). In this task, sustained successful performance is more difficult with shorter stimulus presentations and ISIs (which were equal within a trial). Thus, our dependent measure was the shortest stimulus duration/ISI for trials in which subjects were able to perform the task at 85% accuracy, referred to as ISI for simplicity.

Baseline differences between the two groups were compared using t-tests and Fisher’s exact test. The principal analyses were performed under a Repeated Measures Mixed Model (MMRM) with time represented by discrete visits. The model included fixed effect terms for treatment group, visit and their interaction. The covariance model for the repeated measures was assumed to follow a compound symmetry covariance matrix, which is equivalent to assuming a random participant-specific intercept. Estimated contrasts include differences between treatment groups at each visit, changes over time for each group and group by time interactions, which are changes over time in difference between treatment groups. In cases where the response was measured at more than two time points, such as ISI and SANS, the model contains multiple parameters that represent group by time interaction effects. In these cases a claim of significance is made only when a test of the null hypothesis that all the relevant parameters are equal to zero yields a p-value less than 0.05. These mixed model results were produced by using SAS PROC MIXED (version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

3. Results

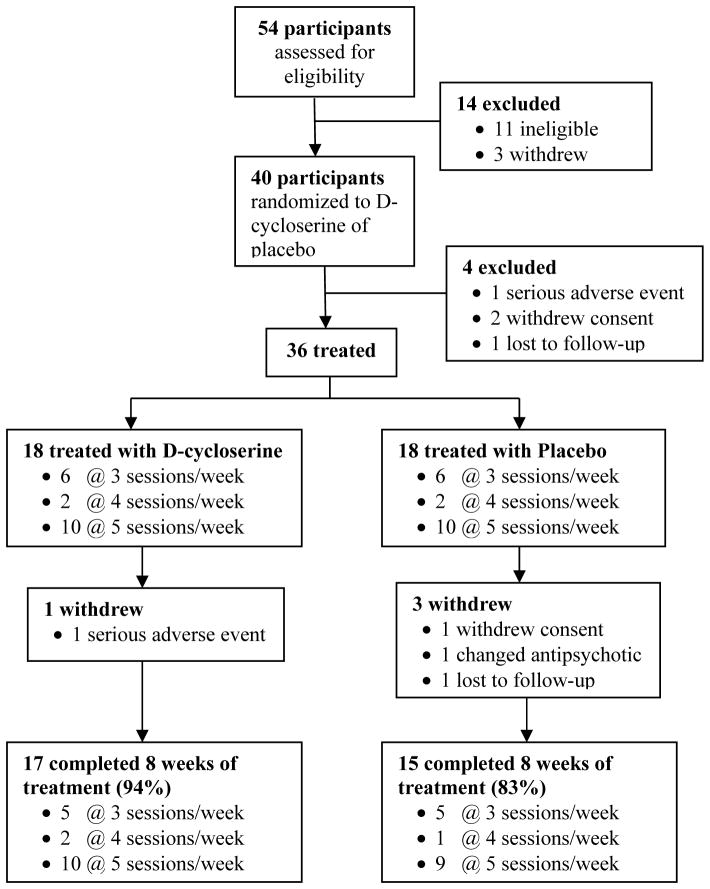

Fifty-four schizophrenia patients were enrolled; 40 were randomized, 36 received at least one dose of DCS or placebo, and 32 completed the 8 week trial (Figure 1). Subjects assigned to DCS did not differ from the placebo group on any demographic or clinical variable at baseline (Tables 1 & 2). Although DCS-assigned subjects tended towards poorer performance on the auditory discrimination task at baseline (Figure 2A), this difference was not statistically significant (t(130)=1.2, p=0.22). Subjects completed 26.1 cognitive remediation sessions on average, which also did not differ between treatment groups (t(34)=1.3, p=0.20). DCS was well-tolerated and side effects did not differ between groups. However, one subject in the DCS treatment group was hospitalized with worsening of psychosis after receiving one dose of study drug; he had missed one dose of depot antipsychotic.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants involved in study.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of entire sample

| D-cyclo | Placebo | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 48.8 (11.5) | 46.2 (13.3) | ||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 16 | 88.9 | 15 | 83.3 | 31 | 86.1 |

| Female | 2 | 11.1 | 3 | 16.7 | 5 | 13.9 |

| Racea | ||||||

| White | 10 | 55.6 | 14 | 77.8 | 24 | 66.7 |

| Black/African American | 5 | 27.8 | 3 | 16.7 | 8 | 22.2 |

| Asian | 1 | 5.6 | 1 | 5.6 | 2 | 5.6 |

| Other | 1 | 5.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.8 |

Two participants (11.1%) were Latino and both were in the placebo group

Table 2.

Baseline range, mean and standard deviation for study variables

| D-cycloserine | Placebo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Range | Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | |

| MATRICS | ||||||

| Speed of Processing | 9–78 | 37.0 | 17.8 | 22–66 | 34.0 | 11.1 |

| Attention/Vigilance | 11–61 | 41.4 | 12.7 | 22–63 | 41.2 | 12.4 |

| Working Memory | 13–51 | 39.1 | 9.1 | 26–67 | 47.4 | 11.3 |

| Verbal Learning | 28–67 | 38.4 | 11.4 | 21–67 | 42.3 | 13.3 |

| Visual Learning | 19–62 | 39.2 | 12.8 | 15–57 | 33.3 | 11.4 |

| Reasoning & Problem Solving | 28–65 | 40.4 | 10.1 | 31–58 | 40.9 | 8.7 |

| Social Cognition | 19–51 | 36.1 | 8.5 | 23–55 | 37.6 | 9.6 |

| Composite | 6–68 | 32.1 | 13.4 | 11–62 | 33.0 | 13.8 |

| SANS Total | 3–48 | 24.6 | 13.5 | 7–49 | 25.8 | 10.7 |

| PANSS Total | 43–88 | 61.8 | 11.4 | 44–95 | 64.1 | 15.5 |

| CDSS | 0–11 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 0–9 | 3.4 | 3.1 |

| GAS | 40–63 | 53.7 | 6.5 | 25–62 | 50.8 | 11.2 |

| QoL | 44–115 | 71.8 | 18.5 | 47–95 | 71.4 | 15.6 |

| ISIa | 40–311 | 163.5 | 86.5 | 29–446 | 124.8 | 93.0 |

Auditory Discrimination Task, all enrolled

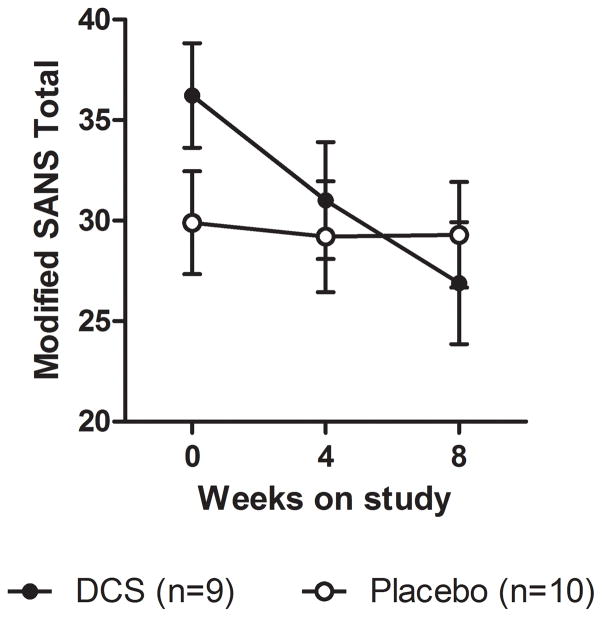

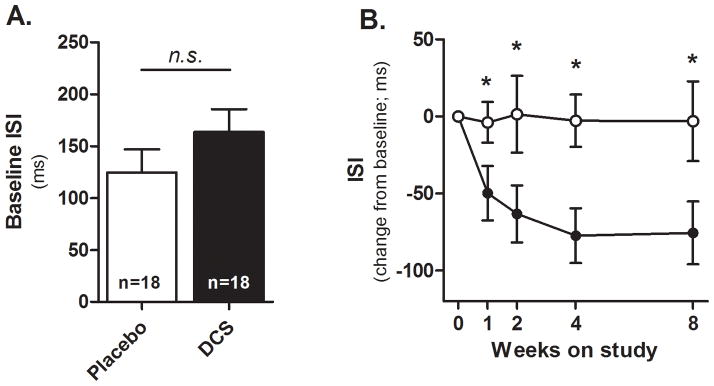

Figure 2. D-cycloserine facilitates auditory discrimination memory.

A) Baseline performance. B) Performance across the 8-week trial, expressed as a change from baseline. All assessments were made prior to DCS (black) or Placebo (white) administration. *p<0.05 vs. Placebo, n.s. = not significant (p>0.05). Error bars = standard error of the mean.

DCS was associated with significant improvement in performance on the auditory discrimination task compared to placebo (Figure 2B); the Group × Visit interaction was significant (F(4,130)=3.3, p=0.01). Contrasts between DCS and placebo at individual visits revealed statistically significant differences at each of the week 1, 2, 4 and 8 visits (p values <0.05). In contrast, subjects treated with DCS did not improve their performance on the MATRICS composite score (t(31)=0.13, p=0.90) or on any domain score (p values > 0.05), whereas the placebo group significantly improved on the MATRICS composite score (t(31)=2.1, p=0.04; Table 3), with marginal improvements on domains 3 (working memory; t(31)=1.92, p=0.06) and 5 (visual learning; t(31)=2.02, p=0.053). Improvement on the MATRICS battery in the placebo group was superior to the DCS group on domain 5 only (t(31)=−2.2, p=0.035).

Table 3.

Change after 8 weeks from baseline in MATRICS score

| Placebo | D-cycloserine | Between Group Diff. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Est. | SE | p-value | Est. | SE | p-value | Est. | SE | p-value | |

| MATRICS | |||||||||

| Speed of Processing | 1.89 | 1.74 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 1.69 | 0.81 | −1.49 | 2.42 | 0.54 |

| Attention/Vigilance | −0.01 | 1.72 | 1.00 | −0.25 | 1.67 | 0.88 | −0.24 | 2.40 | 0.92 |

| Working Memory | 3.11 | 1.62 | 0.06 | 2.57 | 1.57 | 0.11 | −0.55 | 2.26 | 0.81 |

| Verbal Learning | −1.00 | 1.86 | 0.59 | 1.07 | 1.81 | 0.56 | 2.07 | 2.60 | 0.43 |

| Visual Learning | 3.85 | 1.91 | 0.05 | −2.01 | 1.86 | 0.29 | −5.87 | 2.67 | 0.04 |

| Reasoning & Problem Solving | 1.34 | 1.57 | 0.40 | −1.63 | 1.53 | 0.29 | −2.97 | 2.19 | 0.18 |

| Social Cognition | 3.27 | 2.10 | 0.13 | 1.52 | 2.05 | 0.46 | −1.74 | 2.93 | 0.56 |

| Composite | 2.78 | 1.31 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 1.27 | 0.90 | −2.62 | 1.82 | 0.16 |

Response of negative symptoms measured by the modified SANS total score did not differ between treatment groups; however, when the analysis was restricted to subjects with clinically-significant negative symptoms at baseline (SANS ≥ 20, n=19), DCS was associated with significant improvement compared to placebo (Group × Visit: F(2,36)=4.3, p=0.02) (Figure 3). The DCS group exhibited a mean 26% reduction in SANS total score compared to 2% in the placebo group; only the affective flattening subscale was significantly improved compared to placebo (Group × Visit: F(2,36)=8.6, p<0.001). Baseline group differences in this restricted analysis did not reach statistical significance (t(36)=1.5, p=0.15).

Figure 3. Eight week change in SANS total score for participants with clinically significant negative symptoms at baseline.

Error bars = standard error of the mean.

The number of CR sessions completed by participants did not significantly correlate with change in auditory discrimination, negative symptoms or general cognitive performance for either placebo- or DCS-treated subjects (est. correlations <0.5). We also found only a low correlation between SANS improvement and improvement on the auditory discrimination task in placebo- or DCS-treated subjects (est. correlations <0.5).

4. Discussion

The primary finding of this study was that once-weekly DCS enhanced long-term memory (LTM) on the practiced auditory discrimination task but did not generally improve cognitive performance on other, unpracticed, tests. In contrast to the DCS group, the placebo group exhibited significant cognitive improvement overall on the MATRICS battery, especially domain 5 (visual learning). The possibility that enhanced learning on the auditory discrimination task with DCS came at the cost of impaired performance in other domains requires further study. We also replicated our previous finding of negative symptom improvement with once-weekly DCS (Goff et al., 2008), but only in subjects with clinically-significant negative symptoms at baseline. The cut-off (SANS≥20) used for this post hoc analysis has been used in prior studies, including the CONSIST trial (Buchanan et al., 2007; Goff et al., 1999). However, because this was not an a priori analysis, and left us with a small sample size, a larger trial of once-weekly DCS specifically designed to study negative symptoms is needed.

The observed enhancement of auditory discrimination memory is consistent with a large body of evidence from animal studies demonstrating facilitation of memory consolidation with DCS (Davis, 2006; Davis et al., 2011), including auditory discrimination memory (Thompson et al., 1997). It is also consistent with our previous finding in schizophrenia subjects of enhanced recall of narrative themes on the Logical Memory Test (Goff et al., 2008). As illustrated in Figure 2B, auditory discrimination improvements occurred mainly within the first four weeks of the study. There are several possible explanations for this. First, learning curves tend to be negatively accelerating, with the greatest gains happening early in training. If DCS-treated subjects reached asymptotic performance by week four, then further learning would be minimal and DCS effects should diminish. This seems likely, as DCS subjects reached a plateau ISI of 86 milliseconds by week four, within range of a previously reported plateau (70 ms) using the same task but a less conservative accuracy criterion (67%; Keefe et al., 2012), and nearly identical to that reported in another study using an 85% accuracy criterion (Murthy et al., 2012). This interpretation is supported by recent studies of exposure therapy for anxiety, which demonstrate that DCS improves memory only when significant within-session learning is achieved (Smits et al., 2013a,b). However, it is also possible that tachyphylaxis developed in latter weeks, despite the once-weekly dosing schedule. In rats, a dosing interval of 48 hours produced marked loss of effect after repeated dosing whereas a hiatus of 4 weeks was associated with a recovery of DCS effectiveness (Parnas et al., 2005). In human studies of DCS augmentation of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for anxiety, the efficacy of DCS compared to placebo decreases with increasing duration of once-weekly dosing, possibly reflecting tolerance with repeated dosing (Norberg et al., 2008). Further, in extinction studies DCS facilitates new learning only; if an animal has previously been trained to extinguish conditioned fear, DCS does not improve subsequent extinction to the same stimulus (Langton and Richardson, 2008). This preferential effect on novel learning could also diminish DCS effectiveness over time in CR sessions in which exercises are repeated. Consistent with this explanation, in a recent cross-over trial of DCS augmentation of CBT for delusions, we found that DCS only enhanced efficacy if administered prior to the first CBT session (Gottlieb et al., 2011).

Several aspects of our auditory discrimination data warrant further discussion. First, it is somewhat surprising that placebo-treated subjects failed to improve despite completing more than 20 training sessions. Others have reported significant auditory discrimination learning with more extensive Brain Fitness training (Fisher et al., 2009; Murthy et al., 2012), and one study found significant improvements after 20 training sessions (Keefe et al., 2012). It is likely that auditory discrimination gains are more variable with moderate amounts of training and require greater statistical power to detect small effect sizes. However, we do not view this failure to learn as a limitation in the present study, since sub-optimal learning protocols can be ideal for demonstrating nootropic drug effects (Cain et al., 2004; Walker et al., 2002). Second, it is possible that the improvement observed in the DCS group represents regression to the mean rather than learning. However, we view this as unlikely since subjects were randomized, a separate placebo-control group was employed, and auditory discrimination baselines for the DCS and placebo groups were statistically indistinguishable (Figure 2A). Finally, we observed no significant correlation between the number of CR sessions completed and the amount of improvement on the auditory discrimination task. Although no such relationship has been reported in the literature, it was expected. It is possible that the small sample sizes and weaker than normal training prevented the observation of this expected relationship.

Contrary to our initial hypothesis, the DCS-associated memory enhancement was limited to the auditory discrimination task and did not generalize to performance on the MATRICS battery, despite exercises in the CR program designed to generally improve memory. The explanation for this finding is not clear. The Brain Fitness Program was developed in part according to theories of “bottom up” neuroplastic enhancement; these theories posit that improvement of fundamental deficits of sensory processing should translate into improvement in higher cortical function by providing more accurate perceptual inputs (Adcock et al., 2009). In support of this model, Adcock and colleagues (2009) found a significant correlation between improvements in auditory discrimination and improvements in global cognitive functioning (r=0.39). However, others have reported large auditory discrimination improvements with the Brain Fitness Program that do not correlate with general cognitive performance (Murthy et al., 2012) or the MATRICS battery (Keefe et al., 2012). Our results are more consistent with these latter studies and suggest that auditory discrimination gains are neither necessary nor sufficient for global cognitive gains; placebo-treated subjects showed no improvement on the discrimination task but did improve on the MATRICS battery, whereas DCS-treated subjects improved on the discrimination task but not the MATRICS battery. While training in sensory perception may improve higher-level cortical representations, it is not clear that perceptual training generalizes beyond the specific cues that are practiced (Ahissar et al., 2009) and might even interfere with other learning. For example, Fisher and colleagues (2009) found that schizophrenia subjects who practiced at computer games improved in visual learning but exhibited a decline in performance on verbal memory. Our findings are suggestive of a use-dependent selective enhancement of synaptic plasticity rather than a more generalized enhancement of neuronal plasticity.

Other possibilities may explain this apparent dissociation between auditory discrimination gains and general cognitive ability with DCS treatment. First, it is likely that auditory discrimination training was facilitated by DCS because it was the initial, most highly practiced, and only directly-assessed skill. Smaller gains in less-practiced CR tasks could easily have been missed by the indirect MATRICS assessment. Alternatively, DCS may only facilitate specific types of learning, though this remains unclear. In healthy animals, DCS improves memory on a wide range of appetitive and aversive tasks (Bailey et al., 2007; Flood et al., 1992; Matsuoka and Aigner, 1996; Parnas et al., 2005; Quartermain et al., 1994). Another possibility is that DCS may have particular efficacy in reversing core cognitive deficits in schizophrenia, such as NMDAR-dependent LTM processes in cortex. Compared to healthy controls, schizophrenia patients show deficits in LTM for procedural learning (Manoach et al., 2010) and fear extinction (Holt et al., 2009), and these deficits are associated with diminished sleep spindles (Wamsley et al., 2012) and reduced PFC activation (Holt et al., 2012). Further, auditory discrimination learning (Dale et al., 2010) and cortical expression of the NR2C subunit of the NMDAR are reduced in schizophrenia (Beneyto et al., 2008). Although NR2C function has not been directly linked to auditory discrimination memory, cortical NMDA receptors are required (Schicknick and Tischmeyer, 2006). Thus, DCS, which preferentially activates NR2C-containing NMDARs, may selectively reverse auditory discrimination deficits without strongly affecting other cognitive processes that may be less NR2C-dependent. This may explain why DCS enhances delayed memory for the Logical Memory Test in schizophrenia patients (Goff et al., 2008), but not in healthy controls (Otto et al., 2009).

It is noteworthy that the effect of DCS on negative symptoms appears to reflect a different mechanism than the effect on memory. First, in the present study, negative symptom improvement with once-weekly DCS did not significantly correlate with improvement in auditory discrimination and, in a previous study (Goff et al., 2008), did not correlate with DCS-associated improvement in explicit memory. Second, memory effects of DCS are observed after a single dose and attenuate with daily dosing (Parnas et al., 2005), whereas effects on negative symptoms develop gradually with repeated dosing (Goff et al., 1999). Third, DCS may affect memory and negative symptoms by acting on different brain regions. We previously observed a significant correlation between improvement of negative symptoms with DCS and increased perfusion of the left temporal lobe during a verbal fluency task (Yurgelun-Todd et al., 2005). We also observed an association between negative symptoms and activation deficits in hippocampus and other limbic structures during fear conditioning (Holt et al., 2012). The mechanism by which DCS enhances memory is not clear, although animal and human studies have implicated consolidation processes in the PFC (Kalisch et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2009) and basolateral amygdala (Lee et al., 2006; Yang and Lu, 2005). PFC is a likely site of action; deficits in fear extinction recall in schizophrenia are associated with decreased activation of ventromedial PFC (Holt et al., 2012) and, in rats, NMDAR antagonists applied to ventromedial PFC impair consolidation of fear extinction (Burgos-Robles et al., 2007; Sotres-Bayon et al., 2009). It has also been suggested that DCS may act by modifying thalamic oscillations, which modulate memory consolidation in PFC (Lisman et al., 2010). Future studies are needed to examine the pathways by which DCS may be affecting LTM and negative symptoms, as well as optimal dosing strategies to achieve therapeutic benefit.

In conclusion, once-weekly DCS facilitated auditory discrimination memory but cognitive function as measured by the MATRICS battery showed no improvement. This pattern suggests that DCS, by promoting synaptic plasticity, may increase efficiency for practiced tasks only. The improvement of negative symptoms in subjects who were symptomatic at baseline is consistent with results of a previous trial and may represent a mechanism of DCS action that is independent of memory enhancement. Taken together, these results suggest a potential role for once-weekly DCS to facilitate training in psychosocial interventions, such as CBT or social skills training, and in some patients, negative symptoms might improve as well.

Contributor Information

Christopher K. Cain, Email: ccain@nki.rfmh.org.

Margaret McCue, Email: mmccue@nki.rfmh.org.

Iruma Bello, Email: iruma.bello@nyumc.org.

Timothy Creedon, Email: tcreedon@brandeis.edu.

Dei-in Tang, Email: tang@nki.rfmh.org.

Eugene Laska, Email: laska@nki.rfmh.org.

Donald C. Goff, Email: dgoff@nki.rfmh.org.

References

- Adcock RA, Dale C, Fisher M, Aldebot S, Genevsky A, Simpson GV, Nagarajan S, Vinogradov S. When top-down meets bottom-up: auditory training enhances verbal memory in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2009;35(6):1132–1141. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahissar M, Nahum M, Nelken I, Hochstein S. Reverse hierarchies and sensory learning. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 2009;364(1515):285–299. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JE, Papadopoulos A, Lingford-Hughes A, Nutt DJ. D-Cycloserine and performance under different states of anxiety in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;193(4):579–585. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0817-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beneyto M, Meador-Woodruff JH. Lamina-specific abnormalities of NMDA receptor-associated postsynaptic protein transcripts in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(9):2175–2186. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan RW, Javitt DC, Marder SR, Schooler NR, Gold JM, McMahon RP, Heresco-Levy U, Carpenter WT. The Cognitive and Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia Trial (CONSIST): the efficacy of glutamatergic agents for negative symptoms and cognitive impairments. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1593–1602. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06081358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos-Robles A, Vidal-Gonzalez I, Santini E, Quirk GJ. Consolidation of fear extinction requires NMDA receptor-dependent bursting in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Neuron. 2007;53(6):871–880. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain CK, Blouin AM, Barad M. Adrenergic transmission facilitates extinction of conditional fear in mice. Learn Mem. 2004;11(2):179–187. doi: 10.1101/lm.71504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascella NG, Macciardi F, Cavallini C, Smeraldi E. d-cycloserine adjuvant therapy to conventional neuroleptic treatment in schizophrenia: an open-label study. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1994;95:105–111. doi: 10.1007/BF01276429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale CL, Findlay AM, Adcock RA, Vertinski M, Fisher M, Genevsky A, Aldebot S, Subramaniam K, Luks TL, Simpson GV, Nagarajan SS, Vinogradov S. Timing is everything: neural response dynamics during syllable processing and its relation to higher-order cognition in schizophrenia and healthy comparison subjects. International journal of psychophysiology : official journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology. 2010;75(2):183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalakis ZJ, Christensen BK, Fitzgerald PB, Chen R. Dysfunctional neural plasticity in patients with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(4):378–385. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. NMDA receptors and fear extinction: implications for cognitive behavioral therapy. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience. 2011;13(4):463–474. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.4/mdavis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Ressler K, Rothbaum BO, Richardson R. Effects of D-cycloserine on extinction: translation from preclinical to clinical work. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(4):369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Tenhula W, Morris S, Brown C, Peer J, Spencer K, Li L, Gold JM, Bellack AS. A randomized, controlled trial of computer-assisted cognitive remediation for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):170–180. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09020264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix S, Gilmour G, Potts S, Smith JW, Tricklebank M. A within-subject cognitive battery in the rat: differential effects of NMDA receptor antagonists. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;212(2):227–242. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1945-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dravid SM, Burger PB, Prakash A, Geballe MT, Yadav R, Le P, Vellano K, Snyder JP, Traynelis SF. Structural determinants of D-cycloserine efficacy at the NR1/NR2C NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 2010;30(7):2741–2754. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5390-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn MJ, Killcross S. Clozapine but not haloperidol treatment reverses sub-chronic phencyclidine-induced disruption of conditional discrimination performance. Behav Brain Res. 2006;175(2):271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, Holland C, Merzenich MM, Vinogradov S. Using neuroplasticity-based auditory training to improve verbal memory in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(7):805–811. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08050757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood J, Morley J, Lanthorn T. Effect on memory processing by D-cycloserine, an agonist of the NMDA/glycine receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;221:249–254. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90709-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff DC, Tsai G, Manoach DS, Coyle JT. Dose-finding trial of D-cycloserine added to neuroleptics for negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1213–1215. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.8.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff D, Tsai G, Levitt J, Amico E, Manoach D, Schoenfeld D, Hayden D, McCarley R, Coyle J. A placebo-controlled trial of D-cycloserine added to conventional neuroleptics in patients with schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:21–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff DC, Cather C, Gottlieb JD, Evins AE, Walsh J, Raeke L, Otto MW, Schoenfeld D, Green MF. Once-weekly d-cycloserine effects on negative symptoms and cognition in schizophrenia: An exploratory study. Schizophrenia research. 2008;106(2–3):320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff DC, Hill M, Barch D. The treatment of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;99(2):245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb JD, Cather C, Shanahan M, Creedon T, Macklin EA, Goff DC. D-cycloserine facilitation of cognitive behavioral therapy for delusions in schizophrenia. Schiz Res. 2011;131:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SC, Hillman BG, Prakash A, Ugale RR, Stairs DJ, Dravid SM. Effect of D-cycloserine in conjunction with fear extinction training on extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation in the medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala in rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2013 doi: 10.1111/ejn.12197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman BG, Gupta SC, Stairs DJ, Buonanno A, Dravid SM. Behavioral analysis of NR2C knockout mouse reveals deficit in acquisition of conditioned fear and working memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt DJ, Coombs G, Zeidan MA, Goff DC, Milad MR. Failure of neural responses to safety cues in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(9):893–903. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt DJ, Lebron-Milad K, Milad MR, Rauch SL, Pitman RK, Orr SP, Cassidy BS, Walsh JP, Goff DC. Extinction memory is impaired in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(6):455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker CI, Bruce L, Fisher M, Verosky SC, Miyakawa A, Vinogradov S. Neural activity during emotion recognition after combined cognitive plus social cognitive training in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2012;139(1–3):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch R, Holt B, Petrovic P, De Martino B, Kloppel S, Buchel C, Dolan RJ. The NMDA agonist D-cycloserine facilitates fear memory consolidation in humans. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(1):187–196. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER. The molecular biology of memory storage: a dialogue between genes and synapses. Science. 2001;294(5544):1030–1038. doi: 10.1126/science.1067020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RS, Vinogradov S, Medalia A, Buckley PF, Caroff SN, et al. Feasibility and pilot efficacy results from the multisite Cognitive Remediation in the Schizophrenia Trials Network (CRSTN) randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:1016–22. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton JM, Richardson R. D-cycloserine facilitates extinction the first time but not the second time: an examination of the role of NMDA across the course of repeated extinction sessions. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(13):3096–3102. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Milton AL, Everitt BJ. Reconsolidation and extinction of conditioned fear: inhibition and potentiation. J Neurosci. 2006;26(39):10051–10056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2466-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, Pi HJ, Zhang Y, Otmakhova NA. A thalamo-hippocampal-ventral tegmental area loop may produce the positive feedback that underlies the psychotic break in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoach DS, Thakkar KN, Stroynowski E, Ely A, McKinley SK, Wamsley E, Djonlagic I, Vangel MG, Goff DC, Stickgold R. Reduced overnight consolidation of procedural learning in chronic medicated schizophrenia is related to specific sleep stages. Journal of psychiatric research. 2010;44(2):112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka N, Aigner TG. D-cycloserine, a partial agonist at the glycine site coupled to N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, improves visual recognition memory in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:891–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy NV, Mahncke H, Wexler BE, Maruff P, Inamdar A, Zucchetto M, Lund J, Shabbir S, Shergill S, Keshavan M, Kapur S, Laruelle M, Alexander R. Computerized cognitive remediation training for schizophrenia: An open label, multi-site, multinational methodology study. Schizophrenia research. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Jaussi W, Liebetanz D, Lang N, Tergau F, Paulus W. Consolidation of human motor cortical neuroplasticity by D-cycloserine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(8):1573–1578. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norberg MM, Krystal JH, Tolin DF. A meta-analysis of D-cycloserine and the facilitation of fear extinction and exposure therapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(12):1118–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden KK, Khatri A, Traynelis SF, Heldt SA. Potentiation of GluN2C/D NMDA Receptor Subtypes in the Amygdala Facilitates the Retention of Fear and Extinction Learning in Mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013 doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto MW, Basden SL, McHugh RK, Kantak KM, Deckersbach T, Cather C, Goff DC, Hofmann SG, Berry AC, Smits JA. Effects of D-cycloserine administration on weekly nonemotional memory tasks in healthy participants. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics. 2009;78(1):49–54. doi: 10.1159/000172620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnas AS, Weber M, Richardson R. Effects of multiple exposures to D-cycloserine on extinction of conditioned fear in rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2005;83(3):224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quartermain D, Mower J, Rafferty MF, Herting RL, Lanthorn TH. Acute but not chronic activation of the NMDA-coupled glycine receptor with d-cycloserine facilitates learning and retention. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1994;257:7–12. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90687-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler KJ, Rothbaum BO, Tannenbaum L, Anderson P, Graap K, Zimand E, Hodges L, Davis M. Cognitive enhancers as adjuncts to psychotherapy: use of D-cycloserine in phobic individuals to facilitate extinction of fear. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1136–1144. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schicknick H, Tischmeyer W. Consolidation of auditory cortex-dependent memory requires N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activation. Neuropharmacology. 2006;50(6):671–676. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits JA, Rosenfield D, Otto MW, Marques L, Davis ML, Meuret AE, Simon NM, Pollack MH, Hofmann SG. D-cycloserine enhancement of exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder depends on the success of exposure sessions. Journal of psychiatric research. 2013a;47:1455–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits JA, Rosenfield D, Otto MW, Powers MB, Hofmann SG, Telch MJ, Pollack MH, Tart CD. D-cycloserine enhancement of fear extinction is specific to successful exposure sessions: evidence from the treatment of height phobia. Biol Psychiatry. 2013b;73:1054–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotres-Bayon F, Diaz-Mataix L, Bush DE, LeDoux JE. Dissociable roles for the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and amygdala in fear extinction: NR2B contribution. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(2):474–482. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryavanshi PS, Ugale RR, Yilmazer-Hanke D, Stairs DJ, Dravid SM. GluN2C/GluN2D subunit-selective NMDA receptor potentiator CIQ reverses MK-801-induced impairment in prepulse inhibition and working memory in Y-maze test in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/bph.12518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S, Kirk RC, Abraham WC, McNaughton N. Effects of the NMDA antagonists CPP and MK-801 on delayed conditional discrimination. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1989;98(4):556–560. doi: 10.1007/BF00441959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson LT, Disterhoft JF. Age- and dose-dependent facilitation of associative eyeblink conditioning by D-cycloserine in rabbits. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111(6):1303–1312. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.6.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DL, Ressler KJ, Lu KT, Davis M. Facilitation of conditioned fear extinction by systemic administration or intra-amygdala infusions of D-cycloserine as assessed with fear-potentiated startle in rats. J Neurosci. 2002;22(6):2343–2351. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02343.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wamsley EJ, Tucker MA, Shinn AK, Ono KE, McKinley SK, Ely AV, Goff DC, Stickgold R, Manoach DS. Reduced sleep spindles and spindle coherence in schizophrenia: mechanisms of impaired memory consolidation? Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(2):154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Saito H, Abe K. Effects of glycine and structurally related amino acids on generation of long-term potentiation in rat hippocampal slices. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;223(2–3):179–184. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)94837-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weickert CS, Fung SJ, Catts VS, Schofield PR, Allen KM, Moore LT, Newell KA, Pellen D, Huang XF, Catts SV, Weickert TW. Molecular evidence of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor hypofunction in schizophrenia. Molecular psychiatry. 2013;18:1185–1192. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykes T, Huddy V, Cellard C, McGurk SR, Czobar P. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: Methodology and effect sizes. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:472–485. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Wang Y, Pattwell S, Jing D, Liu T, Zhang Y, Bath KG, Lee FS, Chen ZY. Variant BDNF Val66Met polymorphism affects extinction of conditioned aversive memory. J Neurosci. 2009;29(13):4056–4064. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5539-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YL, Lu KT. Facilitation of conditioned fear extinction by d-cycloserine is mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase cascades and requires de novo protein synthesis in basolateral nucleus of amygdala. Neuroscience. 2005;134:247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurgelun-Todd DA, Coyle JT, Gruber SA, Renshaw PF, Silveri MM, Amico E, Cohen B, Goff DC. Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of schizophrenic patients during word production: effects of D-cycloserine. Psychiatry Res. 2005;138(1):23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]