Abstract

Selective protection of secondary amines as triazenes in the presence of multiple primary amines is demonstrated, with subsequent protection of the primary amines as either azides or carbamates in the same pot. Aminoglycoside antibiotic examples reveal broad functional group compatibility. The triazene group is removed with trifluoroacetic acid and, because of the low barrier to rotation, affords sharp 1H NMR spectra at room temperature.

Ongoing studies in our laboratories in the aminoglycoside field highlighted the challenges of working with highly basic polyamines and the need for selective protection methods.1 In particular we were struck by the need for selective protection of disymmetric secondary amines2 without complications of the NMR spectra by the presence of slowly interconverting conformers. The use of carbamates and amides affords rotamers and thus hinders routine spectral interpretation,3 while sulphonamides require less than ideal conditions for eventual deprotection.4 To solve this problem, we explored the use of a number of alternative protecting groups, required to be rotamer-free and cleavable under mild conditions, before selecting the phenyl triazenes.5

The trisubstituted triazene function has been widely employed in recent years for the protection and/or derivatization of aryl amines, when it is typically introduced by reaction of an arene diazonium salt with either a free or polymer-bound secondary amine.6 Alternatively, the same trisubstituted triazenes can be employed to protect secondary amines where they display a useful tolerance of a range of oxidizing and reducing conditions, yet are readily cleaved on exposure to trifluoroacetic acid.7 A recent report on the palladium-catalyzed carbonylative removal of nitrogen from 1,1-dialkyl-3-aryltriazenes (R2N-N2Ar) affording amides (R2NCOAr) offers the additional possibility of protecting group interconversion in a single step.8

1,3-Disubstituted triazenes, on the other hand, while accessible by the reaction of primary amines with diazonium salts, are much less stable.7c,9 Accordingly such 1,3-disubstituted triazenes are more commonly exploited as nucleophiles in the capture of a range of electrophiles, either inter or intramolecularly.9a,10

In view of the relative instability of the disubstituted triazenes with respect to their trisubstituted congeners, and the anticipated sharp NMR spectra, we considered the possibility of employing the triazene function for the selective protection of secondary amino groups in the presence of primary amino groups. We describe here the reduction of this concept to practice and its application to the selective protection of aminoglycoside antibiotics.

Barriers to rotation about the RR’N-N2Ph’’ bond in 1,1-dialkyl-3-phenyltriazenes have been determined by VT-NMR methods to be in the range 13.8-14.7 kcal.mol−1 depending on the substituent pattern.11 The barrier increases significantly when the phenyl group is replaced by an electron-deficient arene11b,11c or other electron-withdrawing group,12 but is reported to be 1 kcal.mol−1 lower in CDCl3 than in CS2.11c Notably steric bulk in the alkyl groups is reported to have little influence on the barrier to rotation about the N-N single bond, but in the extreme case of 2,2-dimethyl and 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-based triazenes the barrier is reduced to ~11 kcal.mol−1 in CS2. Overall, 1H-NMR spectra recorded in CDCl3 at room temperature for the 1,1-dialkyl-3-phenyltriazenes are expected to be above the coalescence temperature and to be correspondingly sharp.

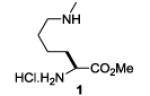

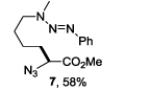

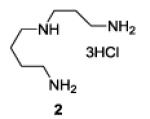

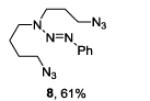

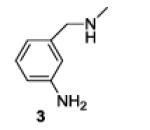

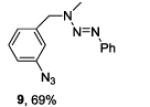

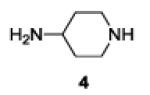

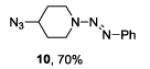

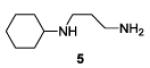

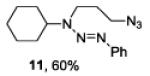

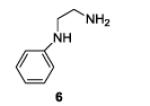

A series of primary and secondary diamines were treated with one equivalent of benzenediazonium tetrafluoroborate in acetonitrile in the presence of powdered potassium or sodium carbonate followed by addition of an excess of imidazolesulfonyl azide and catalytic copper sulfate.13 Work-up and silica gel chromatography then gave the azido triazenes in moderate to good yield as reported in Table 1. Yields are not improved by the use of excess benzenediazonium tetrafluoroborate as this leads to complications in isolation arsing from decomposition of the reagent.

Table 1.

Selective Protection of Diamines as Azido Triazenes.

| entry | substrate | product, % yield |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

| 6 |

|

|

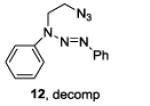

The examples presented in Table 1 (entries 1-5) demonstrate the viability of this two step-one pot protocol: secondary amino groups of varying steric environments can be selectively protected in the presence of one or more primary aliphatic or aromatic amino groups, which can then be converted to the corresponding azides. Entry 6 of Table 1 illustrates the attempted application of the method to a secondary aromatic amine in the presence of a primary aliphatic amine. Unfortunately, while the protocol was successful as judged by NMR and mass spectral investigation of the crude reaction mixture, the product 12 could not be isolated pure after silica gel chromatographic owing to the slow decomposition of the diaryl triazene moiety.

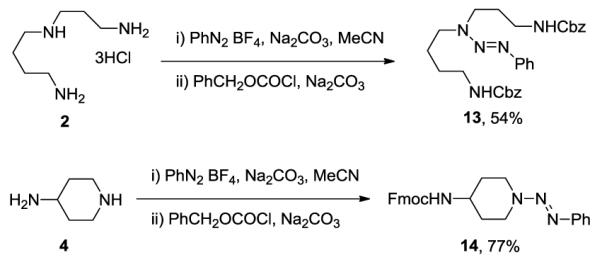

The method is not limited to the conversion of the primary amine functionality to azide groups: Scheme 1 illustrates the conversion of spermidine to a triazeno bis(benzyloxy carbamate) and of 4-aminopiperidine to a triazeno 9-fluorenylmethyl carbamate.

Scheme 1.

Selective protection of polyamines as a triazeno carbamates.

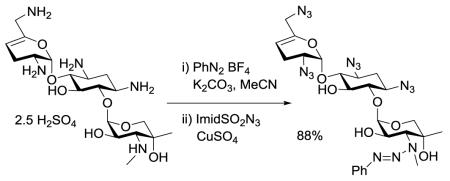

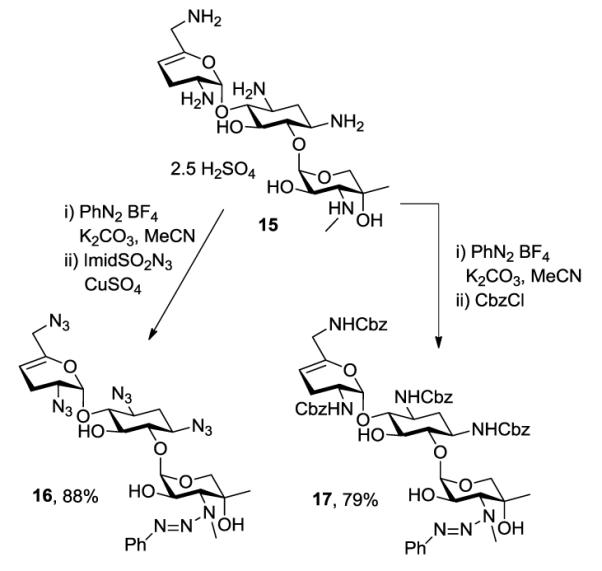

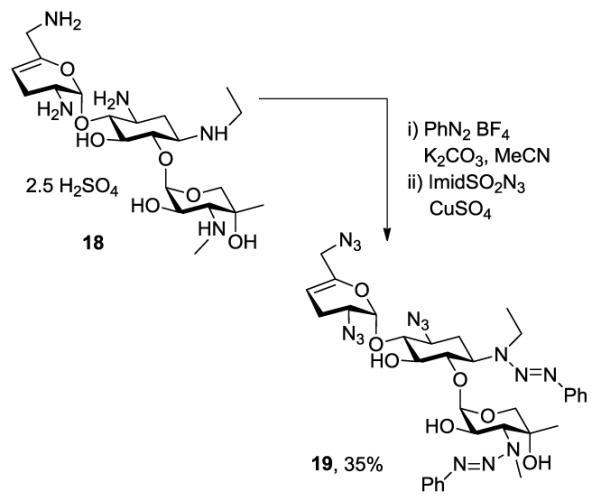

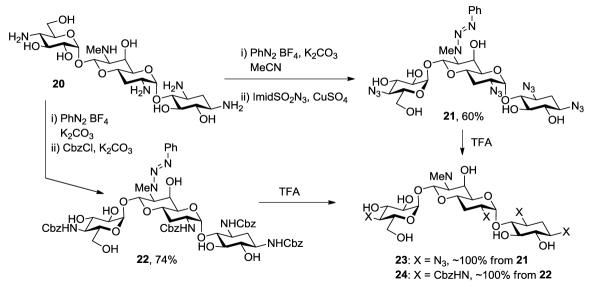

Having established the viability of the method, we explored its application to the aminoglycosides. First, we investigated sisomicin 15 with its single secondary and four primary amino groups. Reaction with one equivalent of benzenediazonium tetrafluoroborate under the standard conditions was followed by treatment with either an excess of imidazolesulfonyl azide or benzyloxycarbonyl chloride resulting in the isolation of 16 and 17, respectively, both in excellent yield (Scheme 2). Application to netilmicin 18, with two secondary amino groups, was also successful, albeit only in moderate yield (Scheme 3). Finally, the method was applied to the monosubstituted deoxystreptamine aminoglycoside apramycin 20, when the azido and carbamate-protected triazenes, 21 and 22 both were obtained in moderate yield (Scheme 4).

Scheme 2.

Application to Sisomicin.

Scheme 3.

Application to Netilmicin.

Scheme 4.

Application to Apramycin and Deprotection

The examples of Schemes 2-4 illustrate the potential of the method for the selective protection of secondary amino groups in complex substrates containing multiple primary amino groups. In addition to showing compatibility with ester functions (Table 1, entry 1) these examples reveal that the selective installation of the triazene moiety may be conducted in the presence of primary, secondary, and tertiary hydroxyl groups, glycosidic bonds, and enol ethers. The apramycin series also serves to illustrate the selective removal of the triazene moiety. Thus, brief treatment of either 21 or 22 with trifluoroacetic acid in a mixture of dichloromethane and ethanol at room temperature gave essentially quantitative yields of the azide and carbamate protected secondary amines 23 and 24, respectively (Scheme 4). The conversion of apramycin to 23 by this simple two-step procedure is noteworthy; direct conversion of apramycin to 23 by copper sulfate-catalyzed treatment with excess triflyl azide gave only a 50% yield, and was complicated by the concomitant formation of a N7′-demethylated pentaazide in yields ranging from 10-20%.14

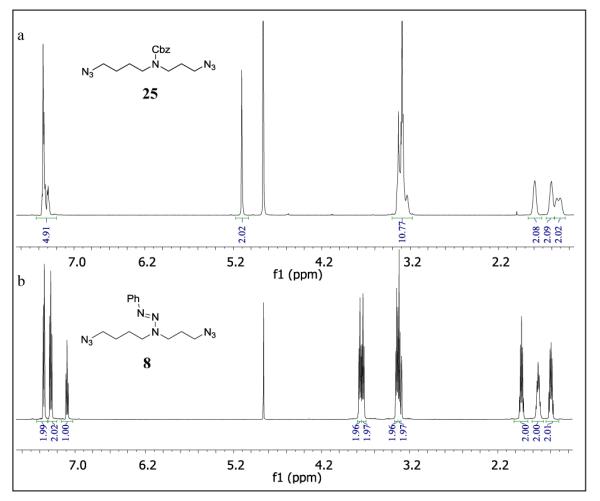

Consistent with expectations, the 1H NMR spectra of the azido triazenes reported herein are mostly sharp in CDCl3 and CD3OD at room temperature (see Supporting Information) with the exception of those compounds that contain multiple Cbz groups. The contrast between the 1H NMR spectra of phenyl triazene protected disymmetric secondary amines and those of the corresponding carbamates is illustrated in Figure 1. The room temperature 1H-NMR spectrum of 25, obtained by sequential treatment of spermidine with imidazole sulfonyl azide and benzyl chloroformate, displays significant broadening of all resonances in this pseudo-symmetric secondary carbamate (Figure 1A). In contrast, the 1H-NMR spectrum of the corresponding diazido triazene 8 is sharp (Figure 1B). The 1H NMR spectra of some azido triazenes, however, do show broadening of selected resonances (see supporting information spectra), such as noted for other trizenes,15 rather than of multiple resonances: as such spectral interpretation is not significantly impaired.

Figure 1.

Room temperature 600 MHz 1H-NMR spectra of 25 (A) and 8 (B) in CD3OD.

The ability to selectively protect secondary amino groups in the presence of primary amino groups in high yield with only a 10% excess of the reagent suggests that the more basic secondary amino groups undergo electrophilic attack by the diazonium ion more rapidly than the primary amino groups. Alternatively, the primary amino groups react with the diazonium salt to give either a disubstituted triazene or other reactive intermediate either reversibly or such that that the diazo moiety is rapidly transferred intermolecularly to the secondary amino group. Whichever pathway is correct, it is clear that a useful method for the selective protection of a secondary amine in the presence of a primary amine is at hand.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Professor Andrea Vasella (ETH) and Erik C Böttger (University of Zurich) for stimulating discussion. We are grateful to the NSF (MRI-084043) for funds in support of the purchase of the 600 MHz NMR spectrometer in the Lumigen Instrument Center at Wayne State University, and to the NIH (GM62160) for partial support of this work.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Full experimental details and copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra for all new compounds. This information is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1)a).Umezawa S. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 1974;30:111–182. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2318(08)60264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Haddad J, Liu M-Z, Mobashery S. In: Glycochemistry: Principles, Synthesis, and Applications. Wang PG, Bertozzi CR, editors. Dekker; New York: 2001. pp. 353–424. [Google Scholar]; c) Wang J, Chang C-WT. In: Aminoglycoside Antibiotics. Arya DP, editor. Wiley; Hobeken: 2007. pp. 141–180. [Google Scholar]; d) Berkov-Zrihen Y, Fridman M. In: Modern Synthetic Methods in Catbohydrate Chemistry; From Monosaccharides to Complex Glycoconjugates. Werz DB, Vidal S, editors. Wiley; Weinheim: 2014. pp. 161–190. [Google Scholar]

- (2)a).Theodoridis G. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:2339–2358. [Google Scholar]; b) Lee SH, Cheong CS. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:4801–4815. [Google Scholar]; c) Laduron F, Tamborowski V, Moens L, Horváth A, De Smaele D, Leurs S. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2005;9:102–104. [Google Scholar]

- (3).For a recent examples in the aminoglycsoide field see: Hanessian S, Maianti JP, Ly VL, Deschenes-Simard B. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:249–256.

- (4)a).Greene TW, Wuts PGM. Protective Groups in Organic Synthesis. 3rd ed Wiley; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]; b) Kocienski PJ. Protecting Groups. 3rd ed Thieme; Stuttgart: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- (5)a).Kimball DB, Haley MM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:3338–3351. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020916)41:18<3338::AID-ANIE3338>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bräse S. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:805–816. doi: 10.1021/ar0200145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6)a).Gross ML, Blank DH, Welch WM. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:2104–2109. [Google Scholar]; b) Young JK, Nelson JC, Moore JS. 1994;116:10841–10842. [Google Scholar]; c) Jones L, Schumm JS, Tour JM. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:1388–1410. [Google Scholar]; d) Nicolaou KC, Li H, Boddy CNC, Ramanjulu JM, Yue T-Y, Natarajan S, Chu X-J, Bräse S, Rübsam F. Chem. Eur. J. 1999;5:2584–2601. [Google Scholar]; e) Liu C-Y, Knochel P. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:7106–7115. doi: 10.1021/jo070774z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Döbele M, Vanderheiden S, Jung N, Bräse S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:5986–5988. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Torres-Garcia C, Pulido D, Albericio F, Royo M, Nicolas E. J. Org. Chem. 2014;79:11409–11415. doi: 10.1021/jo501830w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7)a).Lazny R, Poplawski J, Kobberling J, Enders D, Bräse S. Synlett. 1999:1304–1306. [Google Scholar]; b) Lazny R, Sienkiewicz M, Bräse S. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:5825–5832. [Google Scholar]; c) Recnik S, Svete J, Stanovnik B. Z. Naturforsch. 2004;59b:380–385. [Google Scholar]; d) Rivera A, González-Salas D. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:2500–2504. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Li W, Wu X-F. Org. Lett. 2015;17:1910–1913. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9)a).LeBlanc RJ, Vaughan K. Can. J. Chem. 1972;50:2544–2551. [Google Scholar]; b) Fernández-Alonso A, Bravo-Díaz C. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2007;20:547–553. [Google Scholar]

- (10)a).Vaughan K, LaFrance RJ, Tang Y, Hooper DL. Can. J. Chem. 1985;63:2455–2461. [Google Scholar]; b) Trost BM, Pearson WH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:1054–1056. [Google Scholar]; c) Dahmen S, Bräse S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:3681–3683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Dahmen S, Bräse S. Org. Lett. 2000:3563–3565. doi: 10.1021/ol006440c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Bräse S, Dahmen S, Pfefferkorn M. J. Comb. Chem. 2000;2:710–715. doi: 10.1021/cc000051s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Diethelm S, Schafroth MA, Carreira EM. Org. Lett. 2014;16:3908–3911. doi: 10.1021/ol5016509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11)a).Akhtar MH, McDaniel RS, Feser M, Oehlschlager AC. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968;24:3899–3906. [Google Scholar]; b) Marullo NP, Mayfield CB, Wagnener EH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968;90:510–511. [Google Scholar]; c) Lunazzi L, Cerioni G, Foresti E, Macciantelli D. J. Chem. Soc, Perkin Trans. 1978;2:686–691. [Google Scholar]; d) Sieh DH, Wilbur DJ, Michejda CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:3883–3887. [Google Scholar]; e) Hooper DL, Pottie IR, Vacheresse m., Vaughan K. Can. J. Chem. 1988;76:125–135. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Koga G, Anselme JP. J. Chem. Soc. D, Chem. Commun. 1969:894–895. [Google Scholar]

- (13)a).Goddard-Borger ED, Stick RV. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3797–3800. doi: 10.1021/ol701581g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fischer N, Goddard-Borger ED, Greiner R, Klapotke TM, Skelton BW, Stierstorfer J. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:1760–1764. doi: 10.1021/jo202264r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ye H, Liu R, Li D, Liu Y, Yuan H, Guo W, Zhou L, Cao X, Tian H, Shen J, Wang PG. Org. Lett. 2013;15:18–21. doi: 10.1021/ol3028708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Mandhapati AR, Shcherbakov D, Duscha S, Vasella A, Böttger EC, Crich D. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:2074–2083. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).MacLeod E, Vaughan K. Open Org. Chem. J. 2015;9:1–8. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.