Abstract

We present a comprehensive overview of particulate air quality across the five major metropolitan areas of South Africa (Cape Town, Bloemfontein, Johannesburg and Tshwane (Gauteng Province), the Industrial Highveld Air Quality Priority Area (HVAPA), and Durban), based on a decadal (1 January 2000 to 31 December 2009) aerosol climatology from multiple satellite platforms and detailed analysis of ground-based data from 19 sites throughout Gauteng Province. Satellite analysis was based on aerosol optical depth (AOD) from MODIS Aqua and Terra (550 nm) and MISR (555 nm) platforms, Ångström Exponent (α) from MODIS Aqua (550/865 nm) and Terra (470/660 nm), ultraviolet aerosol index (UVAI) from TOMS, and results from the Goddard Ozone Chemistry Aerosol Radiation and Transport (GOCART) model. At continentally influenced sites, AOD, α, and UVAI reach maxima (0.12–0.20, 1.0–1.8, and 1.0–1.2, respectively) during austral spring (September–October), coinciding with a period of enhanced dust generation and the maximum integrated intensity of close-proximity and subtropical fires identified by MODIS Fire Information for Resource Management System (FIRMS). Minima in AOD, α, and UVAI occur during winter. Results from ground monitoring indicate that low-income township sites experience by far the worst particulate air quality in South Africa, with seasonally averaged PM10 concentrations as much as 136 % higher in townships that in industrial areas.

We report poor agreement between satellite and ground aerosol measurements, with maximum surface aerosol concentrations coinciding with minima in AOD, α, and UVAI. This result suggests that remotely sensed data are not an appropriate surrogate for ground air quality in metropolitan South Africa.

1 Introduction

The impacts of aerosols on human health, visibility, and climate are well documented. There are a number of natural sources of dust, sea salt, sulfate, and organic aerosol, and anthropogenic aerosol primarily derives from fuel combustion. Combustion aerosol can be directly emitted as soot or formed in the atmosphere through photochemical reactions that produce low volatility, secondary sulfate, nitrate, and organic species that either nucleate to form new aerosol or condense onto existing particles. Exposure to particulate pollution is typically worst in urban areas, where anthropogenic emissions are collocated with high population density. The lowest-income fraction of the population tends to experience the worst air quality because the least expensive property (or land available for informal settlements) is often close in proximity to major air pollutant sources like highways, power generation facilities, or industry. In developing countries, low-income households are significantly more likely to utilize non-electricity energy sources such as coal, wood, and paraffin (FRIDGE, 2004; Pauw et al., 2008). Suboptimal burning conditions in domestic settings often result in large emissions of particulates and particulate precursors, leading to high concentrations of PM (FRIDGE, 2004; von Schirnding et al., 2002; Yeh, 2004). In South Africa, the highest concentrations of PM10 and PM2.5 are measured in townships and informal settlements during winter, when domestic burning is most prevalent for heating and cooking, and when emissions are confined in a shallow boundary layer (FRIDGE, 2004; von Schirnding et al., 2002; Yeh, 2004; Wichmann and Voyi, 2005). A number of reports and peer-reviewed articles have sought to characterize air quality in low-income areas of South Africa (e.g., Engelbrecht et al., 2000, 2001, 2002; FRIDGE, 2004; Pauw et al., 2008), but these studies have typically been limited in geographic scope and have not characterized the major metropolitan centers where high densities of South Africans reside.

There is a wealth of remotely sensed air quality information available from satellite platforms, and a number of studies have used aerosol optical depth (AOD or τ ) as a proxy for air quality (Zhuang et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014; Qi et al., 2013; Massie et al., 2006; Kumar et al., 2013; Alam et al., 2011; Kaskaoutis et al., 2007; Carmona and Alpert, 2009; Guo et al., 2011; Marey et al., 2011; Sorooshian et al., 2011; Tesfaye et al., 2011; Sreekanth and Kulkarni, 2013; Singh et al., 2004; Crosbie et al., 2014). AOD (aerosol optical depth) typically displays strong seasonality, with higher AOD observed during periods of peak photochemical production of secondary aerosol – except in areas where either dust generation or biomass burning enhances AOD during other seasons. AOD frequently correlates with ground-based observations of visibility and particulate concentrations, suggesting that it may be an appropriate surrogate for particulate matter at the ground in a number of regions. However, vertical variability in particulate concentrations makes the use of AOD as a proxy for surface air quality tenuous. For example, concentrated plumes of particles transported aloft may enhance AOD significantly but not impact air quality at the ground (e.g., Campbell et al., 2003). Conversely, high concentrations of pollutants in a shallow boundary layer with particle-free air aloft will result in low AOD despite extremely poor air quality at the ground (e.g., Crosbie et al., 2014). While remotely sensed AOD may provide an appropriate measure of air quality in some areas, its general applicability must be evaluated and caution must be exercised when attempting to use column aerosol data as a surrogate for ground particulate concentrations.

Particulates measured at the ground in South Africa are predominately dust, industrial secondary sulfate, and secondary organics (Maenhaut et al., 1996; Piketh et al., 1999, 2002; Tiitta et al., 2014), but significant attention has been paid to the impact of biomass burning on particulates in the country. Regional biomass burning in Southern Africa occurs from June to October (Cooke and Wilson, 1996), and has been characterized extensively by the Southern Africa Fire-Atmosphere Research Initiative (SAFARI) studies of 1992 and 2000. SAFARI-92 and SAFARI-2000 results indicate that transported smoke enhances AOD significantly in South Africa during August and September (Formenti et al., 2002; Campbell et al., 2003; Formenti et al., 2003; Eck et al., 2003; Ross et al., 2003; Magi et al., 2003; Winkler et al., 2008; Magi et al., 2009; Queface et al., 2011; Tesfaye et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2013). The biomass burning emissions that most significantly impact South Africa originate in neighboring countries – particularly Zimbabwe and Mozambique (Magi et al., 2009). Because these emissions are transported in stratified layers aloft (Campbell et al., 2003; Chand et al., 2009), they may impact column aerosol properties such as AOD but not particulate concentrations at the ground.

While transported biomass burning has been demonstrated to impact AOD seasonally, domestic burning – especially for heating and cooking during winter – is the source associated with the highest particulate concentrations in South Africa (Engelbrecht et al., 2000, 2001, 2002). Despite work to characterize emission factors and ambient air quality impacts of domestic burning, studies have been limited in scale to the household or township level and have never considered the dynamics and impact of domestic burning emissions across an entire major population center.

The objective of this work is to characterize aerosol properties in urban centers in South Africa using satellite and ground based measurements, and to determine whether remotely sensed data may be used as a proxy for ground air quality in the region. First we present remotely sensed and modeled column aerosol data related to total light extinction (AOD), particle size (Ångström Exponent, α), total light absorption (ultraviolet aerosol index, UVAI), and AOD contribution from individual chemical components (Goddard Ozone Chemistry Aerosol Radiation and Transport, GO-CART). Satellite data are focused on the five metropolitan and industrial areas of South Africa with highest population density (Cape Town, Bloemfontein, Gauteng Province, Industrial Highveld Air Quality Priority Area or HVAPA, and Durban). We then investigate ground-based measurements of particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5) within the satellite study area that comprises the Johannesburg and Tshwane metropolitan areas (Gauteng Province) in order to understand seasonal, diurnal and regional trends in particulate concentrations across the primary environment types common to all major South African population centers: townships, urban/suburban residential areas, and industrial areas. We finally explore connections between remotely sensed and ground data in order to determine whether satellite-derived aerosol parameters are appropriate surrogates for air quality at the ground in the South African context. This work expands on results from the SAFARI campaigns by investigating decadal averages in aerosol column properties during all seasons and across the country’s major metropolitan areas. Further, it offers a quantitative treatment of particulate air quality characteristic of upper and lower income residential and industrial areas in the country. These results are highly relevant to epidemiologists as well as community, industry, and government stakeholders aiming to understand and improve particulate air quality for South Africans.

2 Data and methods

This study utilizes a combination of remotely sensed and ground-based observations of atmospheric particulates across South Africa. Rather than define study areas based on large geographical regions that require significant data averaging (e.g., Tesfaye et al., 2011), we focused our study of remotely sensed data on five smaller study areas that comprise the five major metropolitan and centers of population density in South Africa (Cape Town, Bloemfontein, Gauteng Province, Industrial Highveld Air Quality Priority Area or HVAPA, and Durban; Fig. 1). We then utilized data from four networks of ground-based air quality monitoring from the South African Air Quality Information System (SAAQIS) for one of these study areas (Gauteng; see Table 1) in order to determine local and diurnal trends in PM10 and PM2.5 and to determine the extent to which remotely sensed measurements of atmospheric particulates are able to capture trends in PM concentrations that are observed at the ground in densely populated urban areas. When seasonal characteristics are described, southern hemisphere summer is defined as December–February (DJF), fall is March–May (MAM), winter is June–August (JJA), and spring is September–November (SON).

Figure 1.

Map depicting satellite study grids, with a summary of area and point sources.

Table 1.

Ground-based air quality monitoring sites in the Gauteng area.

| Site | Network | Type | Data | Date Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexandra | Johannesburg | Township/Domestic Burning | PM10 | 1 Jan 2004 to 31 Oct 2010 |

| Jabavu (Soweto) | Johannesburg | Township/Domestic Burning | PM10 | 14 Jul 2004 to 20 May 2011 |

| Orange Farm | Johannesburg | Township/Domestic Burning | PM10 | 17 May 2004 to 1 Jun 2011 |

| Delta Park | Johannesburg | Urban/Suburban Residential | PM10 | 31 Jul 2004 to 9 Dec 2010 |

| Newtown | Johannesburg | Urban/Suburban Residential | PM10 | 31 Jul 2004 to 1 Jun 2011 |

| Buccleuch | Johannesburg | Traffic | PM10, PM2.5 | 31 Jul 2004 to 1 Jun 2011 |

|

| ||||

| Bodibeng | Tshwane | Township/Domestic Burning | PM10 | 1 May 2012 to 28 Feb 2014 |

| Olivienhoutbosch | Tshwane | Township/Domestic Burning | PM10 | 1 May 2012 to 31 Dec 2013 |

| Pretoria (PTA) West | Tshwane | Industrial | PM10 | 25 Jun 2012 to 5 Oct 2014 |

| Rosslyn | Tshwane | Industrial | PM10 | 20 Jun 2012 to 6 Mar 2014 |

| Ekandustria | Tshwane | Industrial | PM10 | 1 Sep 2012 to 21 Feb 2014 |

| Booysens | Tshwane | Urban/Suburban Residential | PM10 | 1 May 2012 to 28 Feb 2014 |

|

| ||||

| Etwatwa | Ekurhuleni | Township/Domestic Burning | PM10 | 1 Jan 2011 to 30 Sep 2012 |

| Tembisa | Ekurhuleni | Township/Domestic Burning | PM10 | 1 Jul 2011 to 30 Sep 2011 |

|

| ||||

| Diepkloof | VTAPA | Township/Domestic Burning | PM10, PM2.5 | 1 Feb 2007 to 31 Dec 2012 |

| Sebokeng | VTAPA | Township/Domestic Burning | PM10, PM2.5 | 1 Feb 2007 to 31 Dec 2012 |

| Sharpeville | VTAPA | Township/Domestic Burning | PM10, PM2.5 | 1 Mar 2007 to 31 Dec 2012 |

| Zamdela | VTAPA | Township/Domestic Burning | PM10, PM2.5 | 1 Mar 2007 to 31 Dec 2012 |

| Three Rivers | VTAPA | Industrial | PM10, PM2.5 | 1 Feb 2007 to 31 Dec 2012 |

2.1 Remotely sensed aerosol data

Remotely sensed aerosol data from Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Version 5.1 (Remer et al., 2005), Multi-angle Imaging Spectroradiometer (MISR) Version 31 (Diner et al., 2001b, a), and Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS) Version 8 (Herman et al., 1997) were obtained from NASA’s Giovanni Data and Information Services Center (http://disc.sci.gsfc.nasa.gov/giovanni). Data from MODIS included 1 × 1° gridded cloud fraction, aerosol optical depth (AOD or τ ) at 550 nm from both MODIS Aqua and Terra platforms (AOD550), and Ångström Exponent (α) with MODIS Aqua representing spectral dependence of AOD between λ = 550 and 865 nm and MODIS Terra between λ = 470 and 660 nm. MODIS data were available between 1 March 2000 and 31 December 2009 (Terra) and 4 July 2002 and 31 December 2009 (Aqua). We utilized daily 1 × 1° gridded Deep Blue AOD (550 nm) from MODIS (Hsu et al., 2004), which is based on a retrieval algorithm capable of distinguishing particles over bright land surfaces and returning AODs within 20–30 % of ground-based sun photometers (Hsu et al., 2006). AOD at 555 nm (AOD555) and resolution of 0.5 × 0.5° were obtained from MISR for the period 25 February 2000 to 31 December 2009. Ultraviolet Aerosol Index at 1 × 1.25° was obtained from TOMS for the period 24 February 2000 to 14 December 2005, utilizing a minimum UVAI threshold of 0.5 to account for retrieval uncertainties. For all remotely sensed data, a filter was applied to use only data corresponding to cloud fraction < 70 %.

2.2 Goddard Ozone Chemistry Aerosol Radiation and Transport (GOCART) model

Data from the Goddard Ozone Chemistry Aerosol Radiation and Transport model (GOCART; Chin et al., 2002) were used to determine modeled contribution to total AOD550 by individual aerosol components: black carbon, organic carbon, dust, sulfate, and sea salt. Resolution was 2 × 2.5° and data were obtained from NASA’s Giovanni Data and Information Services Center for the period between 24 February 2000 and 31 December 2007.

2.3 Satellite fire data

Data from the MODIS Fire Information for Resource Management System (FIRMS; https://earthdata.nasa.gov/data/near-real-time-data/firms/active-fire-data#tab-content-6) provided a climatology of burn frequency and intensity over southern Africa (0 to 35° S and 5 to 55° E) between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2009. FIRMS data are available for each MODIS overpass and lists the location of identified fires along with fire characteristics which includes fire radiative power (FRP), which captures the intensity of burning within each fire pixel. To capture the frequency and geographical range of burning together with intensity, we report time average FRP integrated at a resolution of 0.5 × 0.5°.

2.4 Air-mass back-trajectory data

NOAA’s Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory (HYSPLIT) model (Draxler and Rolph, 2003) was run using NCAR/NCEP reanalysis data with the isentropic vertical velocity method in order to determine air-mass origin for the Gauteng satellite grid box. Trajectories were obtained from 1 January 2000 through 31 December 2009 ending at the center of the box (26° S, 28° E) at 500 m above the surface. Seasonal trajectory frequency maps were constructed for fall (March–May), winter (June–August), spring (September–November), and summer (December–February) in order to illustrate the most frequent source areas for air arriving in the Gauteng region and aid in interpreting combined satellite and ground results for the region.

2.5 Ground data

Hourly ground-based air quality data were obtained from four different networks reporting to the South African Air Quality Information System (SAAQIS), all located within the Gauteng satellite grid box. Table 1 categorizes individual ground monitoring sites according to both the monitoring network and site type to which they belong, and gives date ranges and data available. Site classifications were made on the basis of site descriptions on the SAAQIS website (available at http://www.saaqis.org.za/NAAQM.aspx), site visits, and personal correspondence with the NGO NOVA Institute, which works extensively in townships and informal settlements. Data were used as per approval from each monitoring network, and were subject to data quality controls. Negative values were discarded, as well as “repeat” values with the same value given for many hours at a time. Where > 30 % of data points were missing over a given time-averaging period, data were discarded.

Ground-based aerosol optical depth and Ångström Exponent are available from multiple Gauteng-area sites in the Aerosol Robotic Network (AERONET). A comparison of ground-based and remotely sensed column aerosol parameters is beyond the scope of this work, but will be presented in a separate publication.

2.6 Meteorology Data

Hourly ground-based meteorology observations were obtained through the South African Weather Service (SAWS) for five sites corresponding to each of the five major metropolitan study areas considered in the study. Data include pressure, precipitation, temperature, relative humidity, wind direction, and wind speed from Cape Town (33.98° S, 18.60° E; 1 April 2001 through 31 December 2009), Bloemfontein (29.12° S, 26.19° E; 25 December 2000 through 31 December 2009), Johannesburg (26.15° S, 28.00° E; 25 December 2000 through 31 December 2009), Ermelo (26.50° S, 29.98° E; 25 December 2000 through 31 December 2009) and Durban (29.97° S, 30.95° E; 25 December 2000 through 31 December 2009).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Study areas: land use and emissions

Locations and sizes of study areas are displayed in Fig. 1. Zoom-in outsets show land use percentage and major emissions sources for each region. In every region there are significant area sources corresponding to biomass burning (veld fires that occur in early to mid-winter) and informal settlements (primarily domestic burning throughout the winter). Mine tailings and waste dumps from gold mining are prevalent in Gauteng, with emissions dependent on wind speed. Petroleum refineries are major point sources in Gauteng, HVAPA and Durban, with some presence in Cape Town. Coal-fired power plants are prevalent through Gauteng and HVAPA, and are collocated with open mining along coal deposits in the region. Overall, Gauteng and HVAPA have by far the highest density of anthropogenic emissions from all sources, including significant on-road emissions.

3.2 Satellite and model results

A number of satellite and model products are available through NASA’s Giovanni Data and Information Services Center (http://disc.sci.gsfc.nasa.gov/giovanni). We focus here on products related to atmospheric particulates, presenting decadal averages (1 January 2000 to 31 December 2009 or some multi-year subset, depending on data availability) of Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD or τ ), Ångström Exponent (α), Ultraviolet Aerosol Index (UVAI), and chemical component contributions to AOD from The Goddard Chemistry Aerosol Radiation and Transport (GOCART) model. Each of these parameters describes a unique aspect of the aerosol column, and results will be presented as follows: (i) a brief description of the parameter, (ii) general regional and seasonal trends, and (iii) discussion of those trends, incorporating other data platforms to support conclusions where appropriate. Main conclusions are synthesized in Sect. 4, and satellite data are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Seasonal averages of satellite data from the MODIS-Aqua, MODIS-Terra, and MISR platforms for each region and as a South Africa average, for the period 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2009.

| Parameter | Region | Platform | Summer | Fall | Winter | Spring |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOD | CPT | Aqua | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.02 |

| Terra | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | ||

| MISR | 0.11 ± 0.13 | 0.13 ± 0.18 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.05 | ||

| Average | 0.09 ± 0.08 | 0.08 ± 0.10 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | ||

| Bloemfontein | Aqua | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.05 | |

| Terra | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | ||

| MISR | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.16 ± 0.05 | ||

| Average | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | ||

| Johannesburg/PTA | Aqua | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.17 ± 0.06 | |

| Terra | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | ||

| MISR | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.05 | ||

| Average | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | ||

| HVAPA | Aqua | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | |

| Terra | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | ||

| MISR | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.05 | ||

| Average | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.05 | ||

| Durban | Aqua | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | |

| Terra | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | ||

| MISR | 0.18 ± 0.09 | 0.13 ± 0.05 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.24 ± 0.08 | ||

| Average | 0.12 ± 0.06 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | ||

| South Africa | Average | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.05 | |

|

| ||||||

| α | CPT | Aqua | 1.19 ± 0.09 | 1.26 ± 0.11 | 1.21 ± 0.12 | 1.39 ± 0.10 |

| Terra | 1.25 ± 0.12 | 1.39 ± 0.14 | 1.40 ± 0.13 | 0.97 ± 0.09 | ||

| Average | 1.22 ± 0.10 | 1.33 ± 0.12 | 1.31 ± 0.13 | 1.18 ± 0.09 | ||

| Bloemfontein | Aqua | 1.18 ± 0.32 | 0.90 ± 0.20 | 0.67 ± 0.06 | 0.92 ± 0.22 | |

| Terra | 0.99 ± 0.34 | 0.82 ± 0.19 | 0.70 ± 0.11 | 0.92 ± 0.30 | ||

| Average | 1.09 ± 0.33 | 0.86 ± 0.19 | 0.69 ± 0.09 | 0.92 ± 0.26 | ||

| Johannesburg/PTA | Aqua | 1.26 ± 0.28 | 0.86 ± 0.12 | 0.69 ± 0.08 | 0.95 ± 0.29 | |

| Terra | 1.20 ± 0.22 | 0.88 ± 0.15 | 0.80 ± 0.19 | 1.16 ± 0.34 | ||

| Average | 1.23 ± 0.25 | 0.87 ± 0.13 | 0.75 ± 0.15 | 1.06 ± 0.31 | ||

| HVAPA | Aqua | 1.13 ± 0.35 | 0.95 ± 0.25 | 0.69 ± 0.07 | 0.97 ± 0.27 | |

| Terra | 1.22 ± 0.23 | 0.79 ± 0.19 | 0.71 ± 0.08 | 1.39 ± 0.24 | ||

| Average | 1.18 ± 0.30 | 0.87 ± 0.22 | 0.70 ± 0.08 | 1.18 ± 0.25 | ||

| Durban | Aqua | 1.50 ± 0.13 | 1.33 ± 0.10 | 1.09 ± 0.11 | 1.68 ± 0.11 | |

| Terra | 1.40 ± 0.12 | 1.29 ± 0.11 | 1.08 ± 0.15 | 1.61 ± 0.10 | ||

| Average | 1.45 ± 0.13 | 1.31 ± 0.11 | 1.09 ± 0.13 | 1.65 ± 0.11 | ||

| South Africa | Average | 1.23 ± 0.24 | 1.05 ± 0.16 | 0.90 ± 0.12 | 1.20 ± 0.23 | |

|

| ||||||

| UVAI | CPT | 1.09 ± 0.28 | 0.73 ± 0.10 | 0.74 ± 0.09 | 0.95 ± 0.21 | |

| Bloemfontein | 0.96 ± 0.30 | 0.74 ± 0.13 | 0.75 ± 0.17 | 0.95 ± 0.23 | ||

| Johannesburg/PTA | 0.94 ± 0.29 | 0.76 ± 0.13 | 0.75 ± 0.15 | 0.97 ± 0.24 | ||

| HVAPA | 0.98 ± 0.29 | 0.73 ± 0.13 | 0.75 ± 0.18 | 0.95 ± 0.22 | ||

| Durban | 1.01 ± 0.27 | 0.72 ± 0.11 | 0.80 ± 0.20 | 0.95 ± 0.24 | ||

| South Africa | Average | 1.00 ± 0.29 | 0.74 ± 0.12 | 0.76 ± 0.17 | 0.95 ± 0.22 | |

3.2.1 Aerosol Optical Depth (AOD)

AOD550 from the MODIS (Aqua and Terra) and AOD555 MISR satellite platforms, and total AOD predicted by GO-CART are presented in Fig. 2. AOD is a measure of the reduction of intensity of light due to scattering and absorption of particles along path length, and is defined for a specific height (z) and wavelength (λ) according to the Beer–Lambert law:

| (1) |

where transmittance, or , is the ratio of radiation intensity at height z to intensity at the top of atmosphere (TOA), for a given wavelength λ. Here, z is the entire atmosphere path length between the ground and TOA, and λ is 550 nm for both MODIS platforms (Aqua and Terra) and 555 nm for MISR. For simplicity, MISR AOD (555 nm) has been converted to equivalent AOD550 (e.g., Schmid et al., 2003) and simply referred to as AOD. AOD is a function of particle extinction efficiency (Qext), which depends on both particle size and absorption efficiency, and particle number concentration. Low values of AOD (< 0.1) correspond to little light attenuation through the atmosphere – meaning relatively clean conditions with low particle concentrations, few large particles, and aerosol number distributions comprised primarily of small, non-absorbing particles. High values of AOD (> 0.3) correspond to significant light attenuation in the atmosphere – meaning high concentrations of large particles such as dust, high concentrations of absorbing aerosol such as black carbon at any size, or some combination of the two. Typical values of AOD range from 0.05 in remote, clean environments to 1.0 in areas of extreme particle concentrations (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2012).

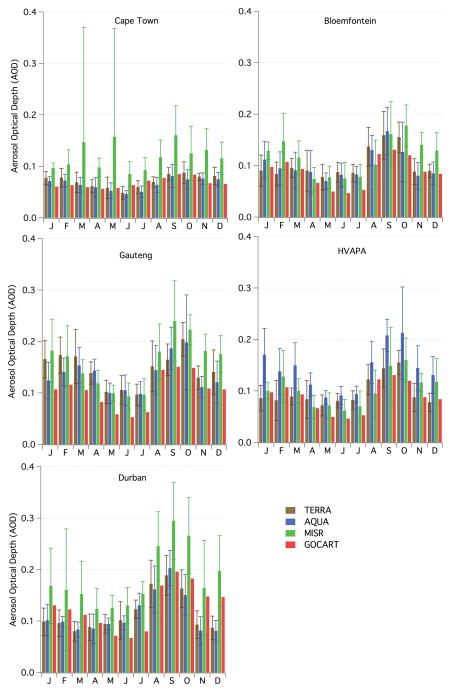

Figure 2.

AOD averages for each region for the period 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2009. Error bars represent one standard deviation in the mean.

Discrepancies in AOD between satellite platforms are generally within uncertainty, and arise due to differences in factors such as processing methods (Abdou et al., 2005), calibration and retrieval algorithms (Kahn et al., 2007), and even measurement time (MODIS-Terra and MISR pass over South Africa between 09:00 and 11:00 LT, while MODIS-Aqua passes over between 13:00 and 15:00 LT). In this study, AOD from MODIS Aqua and Terra are well-correlated with AOD from MISR, with Pearson’s R correlation coefficients (r)>0.7 (not shown), except in Cape Town and Bloemfontein (r = 0.36 and 0.59, respectively). Total AOD modeled by GOCART correlates well with all satellite platforms in all sites (r>0.7). In Cape Town and Durban, MISR AOD appears significantly higher than either MODIS platform or GOCART. The surface at both of these sites displays a great deal of heterogeneity, with satellite grid boxes extending over both bright land and dark ocean surfaces. While estimated biases between MISR and MODIS are expected to be low over uniformly dark surfaces (Kahn et al., 2007), assumptions about surface reflectivity tend to introduce significant discrepancies with increased surface heterogeneity (Chu et al., 2002). MISR is less sensitive to surface characteristics, and so in regions with significant heterogeneity such as Cape Town or Durban, one may expect AOD from MISR to be more accurate.

Considering Fig. 2, AOD is consistently lower in Cape Town than other major metropolitan areas of South Africa, owing to frequent air-mass origin over clean marine areas and minor influence by large or absorbing aerosols. At continentally influenced sites (Bloemfontein, Gauteng, HVAPA, and Durban), there is a maximum in AOD between 0.12 and 0.20 from late winter to early spring. AOD is moderate through summer, averaging 0.08–0.17, and reaches a minimum during late fall and early winter (MJJ), with AOD ranging from 0.05–0.10. AOD is particularly high in magnitude and variability in Durban between August and October, with MISR AOD showing monthly averages approaching 0.3. The seasonal trends evident in Fig. 2 can be explained by considering annual variability in (1) biomass burning and (2) dust generation. The impact of these parameters on AOD is explored below.

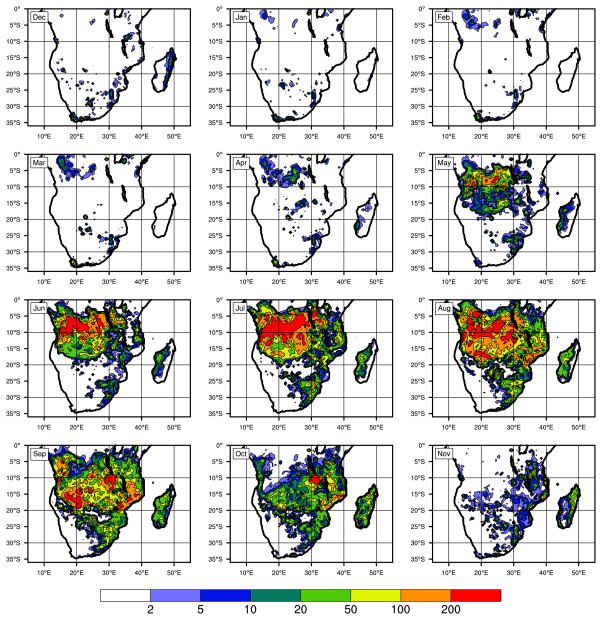

The first and most distinct annual feature across South African metropolitan areas is the cycle in AOD, from minima during late spring and early winter (May–July) to maxima from August to October. This maximum coincides with the burning season in Southern Africa, which has been identified as major regional source of transported aerosol in South Africa (Piketh et al., 1999, 2002; Formenti et al., 2002, 2003; Eck et al., 2003; Ross et al., 2003; Campbell et al., 2003; Sinha et al., 2003; Matichuk et al., 2007; Winkler et al., 2008; Magi et al., 2009; Queface et al., 2011). Figure 3 presents average monthly integrated fire radiative power (FRP) per km2 from 2000–2010 in Sub-Saharan Africa, and indicates that the most significant burning in Southern Africa occurs between May and September and is located in the tropics (between 0 and 20° S). These fires are massive sources of biomass burning emissions that are often transported in stratified layers aloft (Campbell et al., 2003), and this transport significantly impacts aerosol optical properties in South Africa (Formenti et al., 2002; Sinha et al., 2003; Matichuk et al., 2007; Magi et al., 2009).

Figure 3.

Monthly averaged FRP integrated over 0.5 × 0.5° boxes in the Southern Africa Domain over the period 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2009 from MODIS thermal anomaly retrieval.

Winkler et al. (2008) demonstrated that transported biomass burning emissions represent the dominant source of irradiation losses during late winter and early spring in South Africa, with the majority of scattering attributable to carbonaceous aerosols (Magi et al., 2009b). Queface et al. (2011) indicated that transported fire emissions represent the bulk of column aerosol loading between August and October. Strong north-to-south gradients in AOD are observed during the burning season, with significantly higher AOD near sources, where aerosols are small, but highly absorbing and concentrated (Eck et al., 2003; Campbell et al., 2003; Magi et al., 2003; Reid et al., 2005; Magi et al., 2009). Lower AOD is typically observed at downwind receptor sites after plumes have evolved to comprise less absorbing and predominantly Aitken and accumulation mode particles with sufficient condensed water-soluble secondary aerosol species for the particles to serve as cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) (Ross et al., 2003; Eck et al., 2003; Sinha et al., 2003; Reid et al., 2005; Chan et al., 2005; Magi et al., 2009).

On the basis of strong N–S gradients in biomass-burning-related AOD, and the finding that AOD is highest nearest sources (above), it follows that AOD in South Africa is enhanced most significantly by close-proximity fires within South African borders and in neighboring Mozambique and Zimbabwe. These close-proximity fires reach their peak frequency in August, September, and October and coincide with the maxima in AOD observed across all continentally influenced sites in this study. Because AOD is highest in closest proximity to fires, the influence of biomass burning on AOD is expected to be strongest nearer sources in eastern South Africa. Proximity explains the high magnitude and variability of AOD in Durban between August and October, where very close proximity sugar cane field burning typically occurs, releasing high and variable concentrations of absorbing biomass burning particles (LeCanut et al., 1996). Periodically compounding the impact of proximity in eastern South Africa is the so-called “river of smoke” phenomenon (Annegarn et al., 2002), whereby synoptic air flows are occasionally favorable for the transport of subtropical biomass burning into a narrow latitudinal region over the northeastern part of the country – the area that is also closest to high frequency and intensity of seasonal fires.

In addition to coinciding with biomass burning, elevated AOD in August and September is correlated with enhanced generation of windblown dust across South Africa. Ground-based meteorology data from South African Weather Service (SAWS) monitoring sites in each region are presented in Fig. 4, and indicate that in all regions but Cape Town, wind speeds increase in July and August before an enhancement in precipitation in September and October. High winds combined with dry conditions result in generation of wind-blown dust particles, which are both large and strongly absorbing and thereby have strong bearing on AOD. Enhanced AOD coincides with dust generation during August and September, and we therefore suggest that dust may be an additional, previously underestimated factor influencing AOD across South Africa.

Figure 4.

Monthly averaged values of RH, accumulated rainfall, wind speed, and temperature for sites in each satellite study area for the period 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2009. Note different y scales for each site.

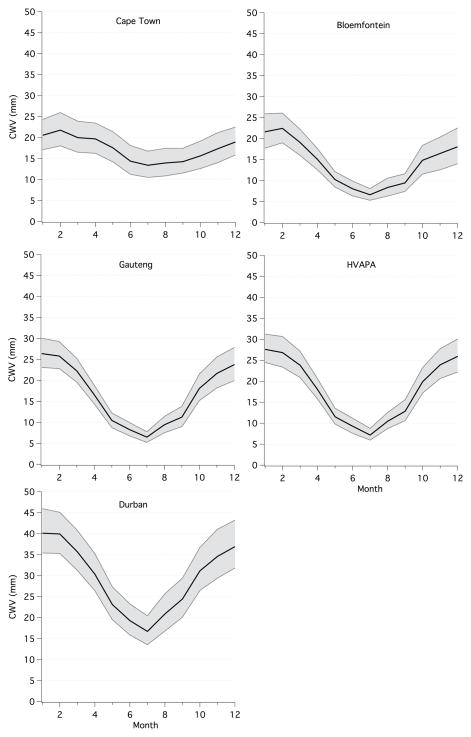

Column water vapor (CWV; Fig. 5) derived from the Modern Era-Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications (MERRA; Rienecker et al., 2011) was analyzed for each site in order to determine whether enhanced water vapor might be a factor contributing to elevated AOD through a mechanism of hygroscopic growth of particles. No significant correlation was found between AOD and CWV at any site, supporting findings in Kumar et al. (2013), which found no relationship between AOD and CWV at a site in rural, northeastern South Africa.

Figure 5.

Average monthly column water vapor (CWV, black line) for the period 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2009, with gray shading representing minimum and maximum monthly CWV during that period.

Overall, AOD values reported here are consistent with those reported by Tesfaye et al. (2011) based on broad, regionally averaged 10-year MISR AOD trends for northern, central, and southern regions of South Africa. The observation of enhanced AOD associated with transported biomass burning aerosol also agrees with similar trends for central and northern South Africa in that work. But overall, AOD is lower than many previously published values over Southern Africa. Queface et al. (2011) reported long-term, monthly averaged AOD ranging from 0.10 to over 0.60 at a site near dense biomass burning sources in Zambia, and monthly averages between 0.17 and 0.30 at a site in northeastern South Africa near the Mozambique border. A strong N–S gradient in AOD is typically observed during biomass burning season in Southern Africa (Eck et al., 2003), with sites to the north experiencing significantly higher AOD than sites in the south due to closer proximity to sources. This suggests that while transported biomass burning aerosol has a clear impact on AOD across the major metropolitan areas of South Africa (except Cape Town), this impact is nonetheless much less pronounced than for sites farther to the north and closer to denser burning sources.

As AOD is frequently used as a proxy for megacity anthropogenic particulate pollution, it is important to view results from South Africa within the context of worldwide megacities. Considering the major metropolitan and industrial areas of Gauteng and HVAPA, seasonally averaged AOD ranged from a minimum of 0.12 in winter to a maximum of 0.17 in spring – values that are a factor of 3–6 lower than those typical of megacities and major industrial areas worldwide. Annual averages of AOD in industrialized and urban areas of Hong Kong and China such as Nanjing, the North China Plain, and Yangtze River are on the order of 0.6–0.8 (Zhuang et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). AOD in Mexico City ranges from a seasonally averaged minimum of 0.2 to a maximum of 0.6 (Massie et al., 2006), and in the Dheli region of India AOD ranges from a seasonal minimum of 0.4 to a maximum during monsoon season of 1.4. So while the Gauteng area and HVAPA areas are characterized as a megacity on the basis of remotely sensed column NOx (Beirle et al., 2004; Lourens, 2012), AOD is significantly lower than typical megacity areas.

3.2.2 Ångström exponent (α)

Monthly averaged Ångström exponent (α) from the MODIS Aqua and Terra platforms is presented in Fig. 6. α captures the spectral dependence of aerosol extinction based on measurements of AOD at two different wavelengths:

| (2) |

where τ1,2 are AODs at wavelengths λ1,2. For small particles in the Rayleigh scattering regime (Dp <0.1 μm), AOD scales with wavelength as ( to ), and α>2 where fine particles dominate. Large particles, on the other hand, are more spectrally neutral and the lack of wavelength dependence of scattering and absorption results in 0<α<1 where coarse particles dominate. α is reported for both MODIS platforms, with Aqua representing spectral dependence of AOD between λ = 550 and 865 nm and Terra between λ = 470 and 660 nm.

Figure 6.

Monthly averaged values of Ångström Exponent (α) for each region for the period 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2009.

α is quantized in such a way that it cannot be used as a quantitative metric for aerosol size integrated through the column (Remer et al., 2005; Levy et al., 2010). Instead, we interpret α results as being qualitatively indicative of the aerosol type present in the column – either fine (values close to 2) or coarse (values between 0 and 1). Due to the qualitative nature of the variable, combined with the fact that α550/865 and α470/660 are highly correlated (r>0.8) at all sites, we will refer to α without specifying wavelength.

Considering Fig. 6, α shows trends similar to AOD (Fig. 2). Generally there is a maximum in α of 1.0–1.8 during spring and through summer, gradually decreasing through fall to reach a minimum of 0.6–1.0 during winter. This suggests that fine particles are most abundant in the column in spring when biomass burning impacts South Africa, agreeing with previous results suggesting that aerosol plumes transported to South Africa tend to be characterized by mainly Aitken mode (0.01–0.1 μm) aerosol (Maenhaut et al., 1996; Eck et al., 2003; Formenti et al., 2003; Reid et al., 2005). α remains high through the hot, photochemically intense summer months, when significant fine, secondary sulfate, nitrate, and organic aerosol is produced from abundant industrial emissions of SO2, NOx, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), respectively (Maenhaut et al., 1996; Piketh et al., 1999; Hirsikko et al., 2012), and when as many as 86 % of days in industrial areas display new particle formation (Hirsikko et al., 2012). This is in contrast to the dry winter months, when α is low and it appears as though particles above the major metropolitan areas of South Africa tend to be larger – suggesting a greater contribution from dust or large soot particles. α is relatively constant throughout the year in Cape Town, indicative of a consistent aerosol size distribution resulting from clean, marine air-mass origin and fairly constant local generation of marine aerosol. At the other coastal site (Durban), α is similarly high throughout the year, but displays a strong seasonal biomass burning signal in spring owing to its location near major sources of small biomass burning particles in local sugar cane fields and in Zimbabwe and Mozambique.

In addition to a clear impact on α by transported biomass burning emissions, maxima and minima in α are highly correlated with CWV in all regions except Cape Town (Fig. 5; 0.64<r<0.98). This result agrees with Kumar et al. (2013), who found that CWV correlated well with α, but not AOD. The relationship between CWV and α is unlikely to be causal, but rather coincidental since wet summer months tend to have suppressed dust generation (fewer large particles and higher α) and enhanced secondary photochemical aerosol production (more small particles and higher α). Overall, α for inland sites (Bloemfontein, Gauteng, HVAPA) is significantly lower on average than for coastal sites (Cape Town and Durban), with α<1 for much of the year. This supports previous findings that coarse particles such as dust form an important contribution to column aerosol loading, and appear to dominate the aerosol size distribution at inland sites (Maenhaut et al., 1996; Piketh et al., 1999; Hirsikko et al., 2012).

Values of α reported here are lower than previously reported in Southern Africa, primarily because major studies of aerosol optical properties in the region have focused on intensive periods of biomass burning. Eck et al. (2003) found high α near biomass burning sources in Zambia (1.8–1.9) during biomass burning season from August-October, while Robles-Gonzalez, et al. (2008) measured α as high as 2.1 in burning regions. Kumar et al. (2013) found strong seasonal variability at a site in northeastern South Africa, with high α (up to 2.9) during burning season, but much lower α (0.5) during the rest of the year. Ranges of α similar to those reported here have been observed in urban and industrial sites in China (ranging from 0.5–1.6 in Qi et al. (2013), with an annual average of 1.25 in Zhuang et al. (2014).

3.2.3 Ultraviolet Aerosol Index (UVAI)

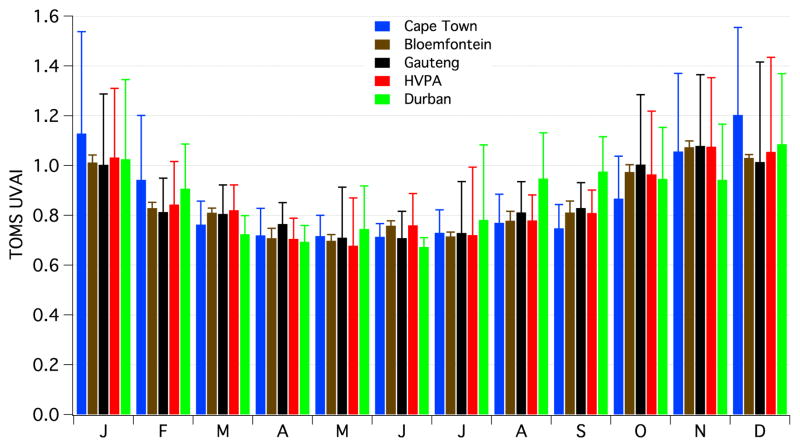

Month averages of Ultraviolet Aerosol Index (UVAI) from the Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS) are presented for each region in Fig. 7. UVAI is a qualitative metric based on the difference between the ratio of absorbing and non-absorbing spectral radiance ratios provided by satellite observations and model calculations. High values of UVAI are associated with high concentrations of strongly absorbing aerosols – namely UV-absorbing soot, smoke, and mineral dust (Hsu et al., 1996), as well as ash and brown carbon. UVAI reaches a maximum of 1.0–1.2 in spring and remains high through summer before decreasing to a minimum of 0.7 during winter. This trend highlights the influence of strongly absorbing biomass burning and dust aerosol, which are most prevalent through spring. Trends in UVAI generally follow those of AOD (Fig. 2) and exhibit good correlation with MISR AOD (r ~ 0.6), except for the Cape Town region where marine aerosol appears to dictate column aerosol properties. The only statistically significant difference between sites is observed in Durban during August and September, when UVAI is elevated relative to other sites owing to significant emissions of strongly absorbing biomass burning emissions from local sugar cane burning (LeCanut et al., 1996).

Figure 7.

Monthly averaged values of UVAI for each region for the period 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2009.

3.2.4 Goddard Ozone Chemistry Aerosol Radiation and Transport (GOCART) model

GOCART model results estimate the contribution of dust, black carbon, organic carbon, sulfate, and sea salt to total column AOD, based on global emissions inventories (Chin et al., 2002). Total estimated GOCART AOD is presented in Fig. 2, and the fraction of AOD attributed to each modeled constituent is displayed in Fig. 8. The monthly averaged fractional contribution of each aerosol component is very consistent across sites, displaying high r for individual components (i.e., dust in Johannesburg compared with dust in Durban for a particular month); typically ~ 0.9. Only Cape Town exhibits a unique trend, owing largely to the significantly larger modeled contribution of dust throughout the year. Modeled dust enhancement in Cape Town is especially pronounced from May through July, when emissions inventories include a large contribution from windblown dust from the nearby Namib Desert. Such an enhancement in the contribution of dust would presumably result in an enhancement in UVAI during May–July and a general trend of elevated UVAI in Cape Town, which is not observed in the data. Further, GO-CART results do not capture the enhancement in dust aerosol expected in late winter to early spring (JAS) based on AOD, UVAI, and enhanced ground wind speed in dry conditions. We therefore suggest that GOCART emissions inventories either significantly overestimate dust in Cape Town or underestimate dust emissions for the rest of South Africa. Given the consistent UVAI across sites in Fig. 7, the strong potential for dust generation in early spring when winds increase but before precipitation arrives, and previous work indicating that >70 % of coarse and > 40 % of fine particle mass is contributed by dust at sites in the Eastern Cape and Highveld (Piketh et al., 1999, 2002), we suggest that GOCART significantly underestimates dust as an aerosol source over the majority of South Africa.

Figure 8.

Monthly averaged fractional contribution of various aerosol components to total AOD as modeled by GOCART. Data are presented for each region for the period 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2009.

3.3 Ground-based sampling results

Ground-based air quality data were obtained through monitoring networks within the Gauteng satellite grid box comprising the cities of Johannesburg and Tshwane (Pretoria), as well as the Ekurhuleni Metro Area (east of the City of Johannesburg) and the Vaal Triangle AQ Priority Area (VTAPA). Table 1 summarizes data type and date ranges available for sites utilized in this study. Sites were classified as one of four types: township or informal settlement sites characterized by some domestic burning emissions (Township/Domestic Burning), developed residential areas in either urban or suburban settings with no domestic burning emissions (Urban/Suburban Residential), areas rich with industrial or power generation activities (Industrial), or sites aimed at capturing on-road sources (Traffic). An emissions summary for the Gauteng area (Fig. 1) indicates that the most significant area sources are from biomass burning (veld fires that occur in early to mid-winter), informal settlements (primarily domestic burning throughout the winter), and mine tailings and waste dumps (emissions dependent on wind speed). The most significant point sources in Gauteng are three coal-fired power plants and two petrochemical refineries in the south, and five steel manufacturing facilities and three cement manufacturing facilities to the south and central part of the region.

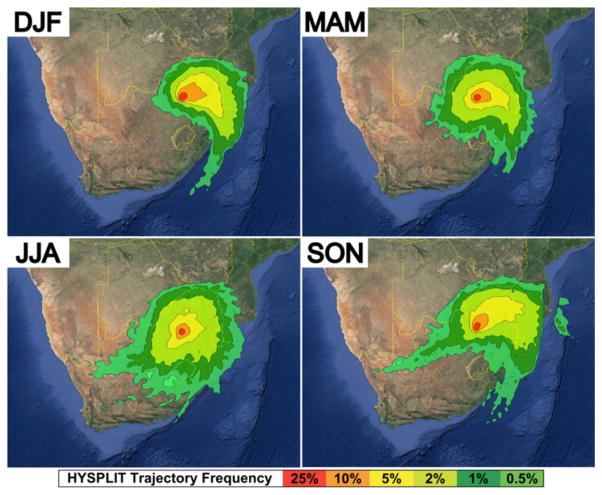

Seasonally averaged HYSPLIT back-trajectory frequencies (Fig. 9) indicate typical air-mass origin for Gauteng. Summer and fall are characterized by air arriving from the east and southeast, while winter is directionally distributed and spring typically sees air transported from the north and east (Zimbabwe and Mozambique), with some contribution from the southwest and southeast. Local meteorology for Gauteng (Fig. 4) was described above and is characterized by cool and very dry winters, with temperature and precipitation increasing through the spring to maxima in the summer. Wind speed increases before precipitation in the spring, resulting in local dust generation from July through September.

Figure 9.

Frequency of air-mass origin based on seasonal averages (summer: DJF, fall: MAM, winter: JJA, spring: SON) of 3-day HYSPLIT back-trajectories for Gauteng for the period 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2009. Colors correspond to percentage frequency with which air mass arriving in Gauteng originates at a particular location within the previous 3 days.

Monthly averages of PM10 and PM2.5, both in absolute magnitude and normalized by each site’s maximum monthly average, are presented in Fig. 10. PM concentrations reach a maximum during winter (June, July, and August) for all except industrial sites. This maximum in PM concentrations corresponds to the coldest months, when the most significant domestic burning activity is expected and boundary layers are extremely shallow (often 50 m or less). The summer maximum in industrial areas may result from photochemistry of industrial precursors and generation of secondary particulates, or may be due to atmospheric dynamics. During winter, industrial stack emissions tend to be released far above the very shallow boundary layer and into a stable atmosphere. During summer, on the other hand, deeper boundary layers extend above stacks and industrial emissions therefore stay within a less stable boundary layer, resulting in mixing of emissions to the ground. The average monthly ratio of PM2.5 to PM10 was calculated for sites with both parameters, and there is no statistically significant monthly variability. This suggests that fine particles comprise a relatively consistent fraction of total particulate concentration throughout the year, despite large changes in overall particulate concentration.

Figure 10.

Monthly averaged PM10, PM2.5 (absolute magnitude and normalized by maximum monthly average) and PM2.5/PM10 for ground monitoring sites. Solid lines represent sites with domestic burning influence, fine dashed lines represent urban/suburban residential areas, and coarse dashed lines represent industrial sites.

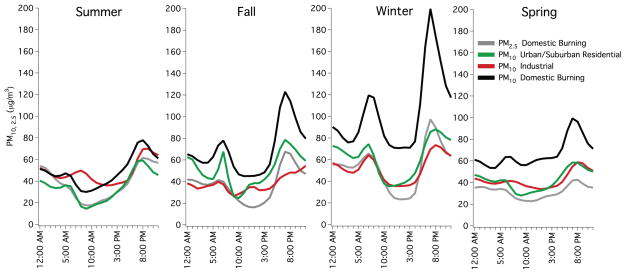

Diurnal averages of PM10 and PM2.5 for each season are presented in Fig. 11. PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations have been normalized by the maximum hourly average for each site for the entire year (typically between 19:00 and 21:00 LT during winter), with the average concentration (in absolute magnitude) for each type of site displayed in the third row of diurnal plots. As was evident in monthly PM data, the highest concentrations occur in township areas where domestic burning is expected, followed by significantly lower PM concentrations in urban and suburban residential areas and the lowest concentrations on average in industrial areas. The clearest feature in the diurnal data is the significant enhancement in particulate concentrations in the morning (06:00–09:00 LT) and evening (17:00–22:00 LT) during all seasons. This trend is especially dramatic during winter, with typical evening PM10 and PM2.5 concentration maxima in township areas of 203 and 105 μg m−3, respectively, with evening PM10 maxima averaging in excess of 400 μg m−3 at some sites.

Figure 11.

Season-averaged diurnal PM10 and PM2.5, with each site normalized by the maximum hourly average across all seasons. Solid lines represent sites with domestic burning influence, fine dashed lines represent urban/suburban residential areas, and coarse dashed lines represent industrial sites.

That these diurnal patterns of enhanced PM concentration in morning and evening are discernible in all seasons is evidence that domestic burning impacts air quality in South Africa throughout the year. The significant enhancement in PM during winter underscores the fact that increased burning during cold months within shallow boundary layers consistently leads to dangerous concentrations of particulates–particularly in the lowest-income residential areas. It should be mentioned that the observed diurnal patterns may also reflect some contribution from on-road emissions – either primary combustion or vehicle-associated dust particles. However, the high density of domestic burning and relatively low density of vehicles in townships compared with other areas suggests that these on-road sources should be minor compared with primary burning emissions. The diurnal ratio of PM2.5 to PM10 is displayed in Fig. 12, and reaches a maximum at all township sites during burning periods, indicating that morning and evening domestic burning activity tends to be a source of small particles.

Figure 12.

Season-averaged diurnal PM2.5/PM10, indicating the diurnal variability in the ratio of fine to coarse particles. Solid lines represent sites with domestic burning influence, fine dashed lines represent urban/suburban residential areas, and coarse dashed lines represent industrial sites.

Average diurnal profiles for each site type are presented in Fig. 13, and diurnal and monthly maxima, minima, and mean values for both PM10 and PM2.5 are presented in Table 3. On average, PM concentrations in townships are 51 % higher than urban/suburban residential sites and 78 % higher than industrial sites, underscoring the importance of domestic emissions as associated with the highest concentrations of particles in the region. The difference between townships and other areas is more distinct in winter, when PM concentrations in townships are 63 and 135 % higher than in urban/suburban residential and industrial sites, respectively. The average wintertime evening maximum in PM10 at townships is 203 μg m−3, with average 1-h concentrations approaching 400 μg m−3 at many township sites. PM10 concentrations are markedly higher than PM2.5 during burning periods, indicating that while domestic burning tends to enhance small particles (above), much of the particulate mass is still associated with large particles (> 2.5 μm). This agrees with results from Wentzel et al. (1999), who found giant dendritic carbonaceous aerosols associated with burning at a township site in Gauteng. There is significant variability in PM concentrations between sites just a few kilometers apart, indicating that the domestic burning that generates the highest concentrations of particulates is highly localized and most dramatically impacts air quality in a small area in the immediate vicinity of emissions. This result indicates that domestic burning PM source strength in low-income areas is highly variable, depending on factors such as the availability of electricity, the method of burning coal or wood, and thermal efficiency of homes.

Figure 13.

Average diurnal PM10 and PM2.5 for each site type.

Table 3.

Average diurnal and monthly values of PM10 and PM2.5 measured at the ground, separated by site type. All concentrations in μg m−3.

| Township | Urban/Suburban Residential | Industrial | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM10 | Diurnal | Max | 408 | 130 | 162 |

| Min | 14 | 8 | 7 | ||

| Monthly | Max | 169 | 88 | 109 | |

| Min | 23 | 28 | 10 | ||

| Mean | 70 ± 31 | 46 ± 16 | 39 ± 23 | ||

|

| |||||

| PM2.5 | Diurnal | Max | 123 | ||

| Min | 12 | ||||

| Monthly | Max | 72 | |||

| Min | 23 | ||||

| Mean | 38± 12 | ||||

Data from two township sites (Alexandra and Bodibeng) have diurnal trends that do not conform to the typical morning and evening PM enhancements typical of low-income areas, and represent intriguing qualitative case studies in the impact of township evolution and informal commercial activity within the township context. Both townships are well-developed, and electricity is the primary fuel used for heating and cooking in households. Qualitatively speaking (data are not available), both townships have a high density of informal food vendors that cook almost exclusively over open flames using inefficient three-stone fires which emit large concentrations of particulates (Bond et al., 2004). Vendors start cooking in the early morning and continue throughout the day and into the evening, which may be the source of the diurnal PM profile which does display moderate concentration enhancements in morning and (more pronounced) evening but also displays elevated PM concentrations at midday.

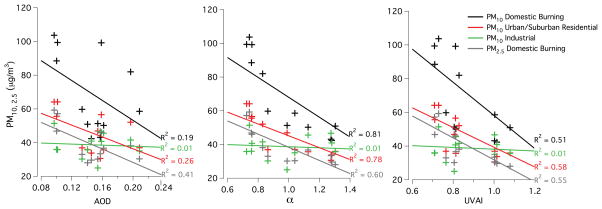

3.4 Satellite data as a proxy for air quality

As discussed above, while there is a trend of using remotely sensed data as a proxy for air quality at the ground, it is necessary to evaluate the appropriateness of this practice in each individual area. Figure 14 displays month-averaged PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations from ground monitoring sites throughout Gauteng, plotted against month-averaged satellite parameters (AOD, α and UVAI) for the Gauteng satellite grid box. Solid lines represent least-squares linear regression fits, considered separately for each ground monitoring site type. R2 values for linear regressions are annotated on the figure. Poor correlation is immediately evident between PM concentrations and both AOD and UVAI, and indeed none of the relationships are statistically significant. Further, what correlation does exist is the opposite of what is expected – since AOD and UVAI both capture overall light extinction due to particles, one would expect elevated PM concentration to correspond with elevated AOD and UVAI. However, the highest PM concentrations occur at the ground during winter months, when AOD and UVAI are at a minimum, while the maxima in AOD and UVAI tend to occur during spring and into the summer, when deeper boundary layers and an absence of domestic burning result PM concentration minima. The correlations between PM concentration and α are statistically significant (except in industrial areas), with low α (larger particles in the column) corresponding to higher concentrations at the ground. We suggest that this correlation is coincidental. High PM concentrations at the ground correspond to domestic burning and occur during winter, when large dust particles appear to be more prevalent in the column (low α). To our knowledge, this is the first published study to report such generalized disagreement between remotely sensed aerosol properties and PM concentrations at the ground.

Figure 14.

Monthly averaged PM for each site type (domestic burning, urban/suburban residential, and industrial) plotted against monthly averaged satellite parameters (AOD, α, and UVAI). Linear least squares regression lines are plotted, with corresponding R2 values listed for each fit.

There are a number of reasons for the discrepancy between ground and satellite data in metropolitan areas of South Africa. First, and most important, there is strong potential for vertical inhomogeneity to result in a disconnect between column and ground aerosol properties in the region. For example, Campbell et al. (2003) and Chand et al. (2009) indicated that biomass burning emissions from fires in the tropics tend to be transported to South Africa in stratified layers aloft, and Tyson et al. (1996) found that there are frequent, persistent, absolutely stable layers at 3 and 5 km above much of South Africa, increasing the potential for stratified plumes of pollutants above the ground. While concentrated plumes of particles in stratified layers above the ground would impact column aerosol properties, they would not affect ground concentrations of particulates unless atmospheric instability caused those particles to be vertically mixed into the planetary boundary layer and to the surface. Therefore, characteristics of column aerosol properties are not necessarily indicative of any trends in ground PM concentrations – particularly in South Africa’s stratified atmosphere.

Next, the highest concentrations of particulates in South Africa are observed during winter, when domestic burning emissions are released into an extremely shallow boundary layer – often on the order of 50 m or less (Tyson et al., 1996). Because these emissions are confined in a layer so close to the ground, it is unlikely that satellite retrievals are able to resolve the difference between the concentrated aerosol layer and the ground itself.

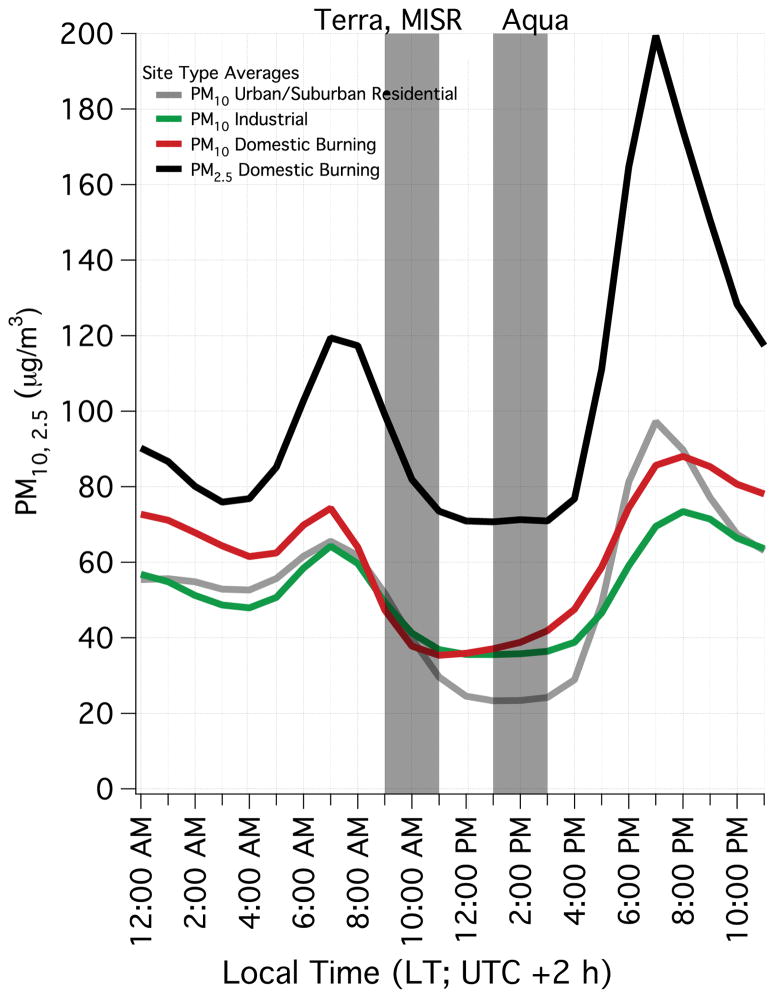

Third is the issue of temporal resolution. Figure 15 shows average wintertime PM10 and PM2.5 diurnal profiles for each site type, with shaded boxes representing the time window in which MODIS-Terra, MISR, and MODIS-Aqua instruments pass over South Africa. MODIS-Terra and MISR (09:00 to 11:00 LT) tend to pass over South Africa on the tail end of enhanced PM concentrations from morning domestic burning, while Aqua’s pass over time (13:00–15:00 LT) coincides with the minimum PM concentrations of the day. While PM concentrations tend to be elevated throughout the day at all sites during winter, the average daily, weekly, and winter PM concentrations at the ground are strongly influenced by morning and evening maxima that are not observed by satellites. Therefore, the discrepancy between satellite passover times and elevated PM concentrations indicates that remotely sensed data are unlikely to capture the trend of significantly enhanced PM concentration at the ground.

Figure 15.

Winter diurnal ground PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations, with shaded gray boxes representing satellite flyover times for MODIS-Terra, MODIS-Aqua, and MISR platforms.

Finally, spatial resolution may be a factor prohibiting satellite data from appropriately representing ground PM concentrations. PM concentrations between township, suburban, and industrial sites just a few km apart are significantly different (Fig. 10), underscoring the significant local variability in PM concentrations resulting from unique source density in each area. Satellite measures of aerosol properties must be averaged over spatial scales on the order of 1 × 1°, which includes many areas with low overall concentrations and areas (e.g., urban/suburban residential and industrial in Fig. 13) where the discrepancy between seasonal profiles of PM do not vary significantly in magnitude. These highly localized gradients in PM at the ground occur on scales much smaller than the resolution of level 2 or level 3 data available from MODIS-Aqua and MODIS-Terra, and indeed level 2 data display no better correlation than the level 3 data presented in this work.

Overall, the problem of extreme PM concentrations at the ground appears to be a highly localized one impacting primarily low-income areas of South Africa, and the vertical integration, low time resolution, and spatial averaging required with satellite data precludes their use in understanding and predicting ground PM characteristics in the South African context.

4 Conclusions

Here we present a comprehensive study of air quality in South Africa’s metropolitan centers, based on decadal averages of remotely sensed aerosol column data and multi-year averages from ground-based air quality sampling sites. Aerosol climatology from satellite platforms was based on AOD, Ångström exponent and UVAI, and GOCART model results were also analyzed. AOD was found to reach a maximum of 0.12–0.20 during late winter and early spring (ASO), corresponding with elevated column concentrations of absorbing aerosol from close-proximity fires in Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and eastern South Africa, as well as from enhanced windblown dust generation during dry and windy months. Minimum AOD of 0.05–0.10 occurs during winter, when domestic burning emissions are highest and air quality at the ground is worst, suggesting that this aerosol is confined to a very shallow layer and does not impact overall column aerosol characteristics despite its importance at the surface. AOD in metropolitan areas of South Africa is a factor of 3–6 lower than reported for megacities worldwide, and is lower than previously reported in the rural northeast part of the country that is closer in proximity to biomass burning sources. Ångström exponent reaches a maximum of 1.0–1.8 during spring and summer at sites closest to biomass burning sources, reflecting the importance of regional fires as sources of small particles. Ångström reaches a minimum of 0.6–1.0 in winter, when dry conditions appear to result in an enhanced contribution of coarse dust particles to column aerosol. Ångström exponent is highly correlated with CWV and is markedly lower at continental sites, suggesting that coarse dust particles contribute significantly to total column aerosol in inland South Africa. UVAI reaches a maximum of 1.0–1.2 during spring and summer, coinciding with the presence of strongly absorbing dust and biomass burning particles. UVAI reaches a minimum of 0.7 in winter, when dust aerosols appear to contribute a larger fraction of column aerosol but integrated column concentrations are very low. Satellite results in Cape Town are significantly different than other sites, reflecting a difference between clean marine versus polluted continental air-mass origins. Overall, satellite data provide a good representation of large-scale, regional, and seasonal trends in column particulates across South Africa.

Ground air quality results are based on PM data from 19 sites in Gauteng province, which is the most significant population and industrial center of South Africa. Ground monitoring sites fall into 4 categories: township areas with close proximity domestic burning, urban/suburban residential areas, industrial areas, and traffic sites directly adjacent to major on-road sources. Based on monthly averages, townships experience 51 and 78 % higher PM10 concentrations than urban/suburban residential and industrial areas, respectively. This quantitatively confirms previous studies indicating that the poorest air quality in South Africa is found in low-income areas (e.g., Engelbrecht et al., 2000, 2001, 2002; FRIDGE, 2004; Pauw et al., 2008). Both PM10 and PM2.5 reach distinct maxima during winter (June, July, or August) in all non-industrial sites, while two maxima are observed in industrial sites and correspond to photochemical particulate production and deeper, unstable boundary layers in summer and domestic burning in winter. Both PM10 and PM2.5 display diurnal patterns at all sites, with elevated concentration in the morning (06:00–09:00 LT) and maximum concentration in the evening (17:00–22:00 LT) in all seasons. These diurnal profiles are especially distinct during winter in low-income areas, with evening PM10 and PM2.5 1 h average mass concentrations reaching 203 and 105 μg m−3, respectively. Monthly and diurnal PM concentrations at the ground vary significantly between sites just a few km apart, underscoring the importance of source strength and density in determining particulate air quality at a highly localized level. This result also indicates that a “typical” low income area is difficult to define solely in terms of the magnitude of particulate concentration.

If satellite measurements of column aerosol properties were an appropriate proxy for air quality at the ground in urban South Africa, one would expect AOD to be positively correlated with PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations. This, however, is not observed, as correlations between AOD and PM are weak and negative. PM10 is negatively correlated with α, suggesting that higher ground PM concentrations are associated with larger particles in the column. We suggest, however, that this correlation is coincidental due to seasonal variation in which high wintertime PM concentrations at the ground occur during the dry season when coarse dust particles contribute an elevated fraction of column aerosol. Other satellite and model products show little correlation with ground PM concentrations, and it appears as though satellites are unable to resolve even extremely high PM concentrations at the ground during winter in South Africa. This discrepancy is likely the result of a combination of atmospheric dynamics (absolutely stable layers aloft, concentrated pollutants transported aloft, and high wintertime PM confined within a very shallow boundary layer) and time and spatial resolution (satellites pass over southern Africa during off-peak times for PM concentration, and data must be averaged over large areas).

The inability of satellites to capture trends in ground PM concentrations in South Africa indicates that monitoring and characterization of air quality in South Africa will require extensive networks of ground monitoring stations producing quality data across the country, as well as intensive multi-platform campaigns aimed at understanding the relationship between ground and remotely sensed air quality data. Further advances in understanding would follow regular monitoring of vertical profiles of criteria pollutants. South Africa’s current monitoring networks are in varying states of functionality and management, meaning that many air quality data time series are either incomplete or poor in quality. Data are controlled individually by each network, so a study like this one requires many different official requests, approvals, and waiting times for data. Further, these monitoring sites tend to be in urban and industrial centers of South Africa like those considered in this work. However, roughly 40 % of South Africa’s population resides in rural settlements, and little is known about air quality in these areas. Based on results presented here, we suggest that a systematic effort be made in South Africa to improve and centralize management, data quality, and data availability amongst existing ground monitoring networks, in addition to an expansion of ground monitoring sites into rural areas.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the South African Weather Service (SAWS) for providing meteorology data from ground monitoring sites and for coordinating ground data from air quality monitoring stations. The authors would also like to thank the air quality monitoring networks in Johannesburg, Tshwane, Ekurhuleni, and the Vaal Triangle Priority Area reporting to SAAQIS. Armin Sorooshian, Ewan Crosbie, and Taylor Schingler acknowledge support in part by Grant 2 P42 ES0494011 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Superfund Research Program, NIH, and the Center for Environmentally Sustainable Mining through TRIF Water Sustainability Program funding. Rebecca M. Garland acknowledges support of a grant from CSIR. This work is based on the research supported in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (grant number 81659) to Stuart Piketh.

References

- Abdou WA, Diner DJ, Martonchik JV, Bruegge CJ, Kahn RA, Gaitley BJ, Crean KA, Remer LA, Holben B. Comparison of coincident Multiangle Imaging Spectroradiometer and Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer aerosol optical depths over land and ocean scenes containing Aerosol Robotic Network sites. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2005;110:2156–2202. doi: 10.1029/2004JD004693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alam K, Qureshi S, Blaschke T. Monitoring spatio-temporal aerosol patterns over Pakistan based on MODIS, TOMS and MISR satellite data and a HYSPLIT model. Atmos Environ. 2011;45:4641–4651. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.05.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Annegarn HJ, Otter L, Swap RJ, Scholes RJ. Southern Africa’s ecosystem in a test-tube: a perspective on the Southern African Regional Science Initiative (SAFARI 2000): commentary. South African J Sci. 2002;98:111–113. [Google Scholar]

- Beirle S, Platt U, Wenig M, Wagner T. Highly resolved global distribution of tropospheric NO2 using GOME narrow swath mode data. Atmos Chem Phys. 2004;2:1913–1924. doi: 10.5194/acpd-4-1665-2004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bond TC, Streets DG, Yarber KF, Nelson SM, Woo J-H, Klimont Z. A technology-based global inventory of black and organic carbon emissions from combustion. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2004;109:D14203. doi: 10.1029/2003JD003697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JR, Welton EJ, Spinhirne JD, Ji Q, Tsay S-C, Piketh SJ, Barenbrug M, Holben BN. Micropulse lidar observations of tropospheric aerosols over northeastern South Africa during the ARREX and SAFARI 2000 dry season experiments. J Geophys Res. 2003;108:8497. doi: 10.1029/2002JD002563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona I, Alpert P. Synoptic classification of moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer aerosols over Israel. J Geophys Res-Atmos (1984–2012) 2009;114:D07208. doi: 10.1029/2008JD010160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan MN, Choi MY, Ng NL, Chan CK. Hygroscopicity of Water-Soluble Organic Compounds in Atmospheric Aerosols? Amino Acids and Biomass Burning Derived Organic Species. Env Sci Tech. 2005;39:1555–1562. doi: 10.1021/es049584l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chand D, Wood R, Anderson T, Satheesh S, Charlson R. Satellite-derived direct radiative effect of aerosols dependent on cloud cover. Nat Geosci. 2009;2:181–184. [Google Scholar]

- Chin M, Ginoux P, Kinne S, Torres O, Holben BN, Duncan BN, Martin RV, Logan JA, Higurashi A, Nakajima T. Tropospheric aerosol optical thickness from the GO-CART model and comparisons with satellite and sun photometer measurements. J Atmos Sci. 2002;59:461–483. doi: 10.1175/1520-0469(2002)059<0461:TAOTFT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chu DA, Kaufman YJ, Ichoku C, Remer LA, Tanra D, Holben BN. Validation of MODIS aerosol optical depth retrieval over land. Geophys Res Lett. 2002;29:MOD2-1–MOD2-4. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.05.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke WF, Wilson JJ. A global black carbon aerosol model. J Geophys Res-Atmos (1984–2012) 1996;101:19395–19409. [Google Scholar]

- Crosbie E, Sorooshian A, Monfared NA, Shingler T, Esmaili O. A Multi-Year Aerosol Characterization for the Greater Tehran Area Using Satellite, Surface, and Modeling Data. Atmosphere. 2014;5:178–197. doi: 10.3390/atmos5020178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diner DJ, Abdou WA, Ackerman TP, Crean K, Gordon HR, Kahn RA, Martonchik JV, McMuldroch S, Paradise SR, Pinty B, Verstraete MM, Wang M, West RA. Level 2 aerosol retrieval algorithm theoretical basis. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology; 2001a. [Google Scholar]

- Diner DJ, Abdou WA, Bruegge CJ, Conel JE, Crean KA, Gaitley BJ, Helmlinger MC, Kahn RA, Martonchik JV, Pilorz SH, Holben BN. MISR aerosol optical depth retrievals over southern Africa during the SAFARI2000 Dry Season Campaign. Geophys Res Lett. 2001b;28:3127–3130. doi: 10.1029/2001GL013188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Draxler RR, Rolph G. HYSPLIT (HYbrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory) model access via NOAA ARL READY website. NOAA Air Resources Laboratory; Silver Spring: 2003. [last accessed 18 Dec. 2013]. ( http://www.arl.noaa.gov/ready/hysplit4.html) [Google Scholar]

- Eck TF, Holben BN, Ward DE, Mukelabai MM, Dubovik O, Smirnov A, Schafer JS, Hsu NC, Piketh SJ, Queface A, Roux JL, Swap RJ, Slutsker I. Variability of biomass burning aerosol optical characteristics in southern Africa during the SAFARI 2000 dry season campaign and a comparison of single scattering albedo estimates from radiometric measurements. J Geophys Res. 2003;108:8477. doi: 10.1029/2002JD002321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht JP, Swanepoel L, Zunckel M, Chow JC, Watson JG, Egami RT. Modelling PM10 aerosol data from the Qalabotjha low-smoke fuels macro-scale experiment in South Africa. Ecol Model. 2000;127:235–244. [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht JP, Swanepoel L, Chow JC, Watson JG, Egami RT. PM2. 5 and PM10 concentrations from the Qalabotjha low-smoke fuels macro-scale experiment in South Africa. Environ Monit Assess. 2001;69:1–15. doi: 10.1023/a:1010786615180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht JP, Swanepoel L, Chow JC, Watson JG, Egami RT. The comparison of source contributions from residential coal and low-smoke fuels, using CMB modeling, in South Africa. Environ Sci Policy. 2002;5:157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Formenti P, Winkler H, Fourie P, Piketh S, Makgopa B, Helas G, Andreae MO. Aerosol optical depth over a remote semi-arid region of South Africa from spectral measurements of the daytime solar extinction and the nighttime stellar extinction. Atmos Res. 2002;62:11–32. doi: 10.1016/S0169-8095(02)00021-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Formenti P, Elbert W, Maenhaut W, Haywood J, Osborne S, Andreae MO. Inorganic and carbonaceous aerosols during the Southern African Regional Science Initiative (SAFARI 2000) experiment: Chemical characteristics, physical properties, and emission data for smoke from African biomass burning. J Geophys Res. 2003;108:8488. doi: 10.1029/2002JD002408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FRIDGE. Tech rep. Airshed Planning Professionals/Bentley West Management Consultants report to the Trade and Industry Chamber/Fund for Research into Industrial Development, Growth and Equity (FRIDGE); Johannesburg: 2004. Study to examine the potential socio-economic impact of measures to reduce air pollution from combustion. Part 1 report: Definition of air pollutants associated with combustion processes. [Google Scholar]

- Guo JP, Zhang XY, Wu YR, Zhaxi Y, Che HZ, La B, Wang W, Li XW. Spatio-temporal variation trends of satellite-based aerosol optical depth in China during 1980–2008. Atmos Environ. 2011;45:6802–6811. [Google Scholar]

- Herman J, Bhartia P, Torres O, Hsu C, Seftor C, Celarier E. Global distribution of UV-absorbing aerosols from Nimbus 7/TOMS data. J Geophys Res-Atmos (1984–2012) 1997;102:16911–16922. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsikko A, Vakkari V, Tiitta P, Manninen H, Gagné S, Laakso H, Kulmala M, Mirme A, Mirme S, Mabaso D, Beukes JP, Laakso L. Characterisation of sub-micron particle number concentrations and formation events in the western Bushveld Igneous Complex, South Africa. Atmos Chem Phys. 2012;12:1895–1934. doi: 10.5194/acp-12-3951-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu N, Herman J, Bhartia P, Seftor C, Torres O, Thompson A, Gleason J, Eck T, Holben B. Detection of biomass burning smoke from TOMS measurements. Geophys Res Lett. 1996;23:745–748. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu NC, Tsay S-C, King MD, Herman JR. Aerosol properties over bright-reflecting source regions, Geoscience and Remote Sensing. IEEE Transactions on. 2004;42:557–569. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu NC, Tsay S-C, King MD, Herman JR. Deep blue retrievals of Asian aerosol properties during ACE-Asia, Geoscience and Remote Sensing. IEEE Transactions on. 2006;44:3180–3195. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RA, Garay MJ, Nelson DL, Yau KK, Bull MA, Gaitley BJ, Martonchik JV, Levy RC. Satellite-derived aerosol optical depth over dark water from MISR and MODIS: Comparisons with AERONET and implications for climatological studies. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 2007;112:2156–2202. [Google Scholar]

- Kaskaoutis D, Kosmopoulos P, Kambezidis H, Nastos P. Aerosol climatology and discrimination of different types over Athens, Greece, based on MODIS data. Atmos Environ. 2007;41:7315–7329. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar KR, Sivakumar V, Reddy R, Gopal KR, Adesina AJ. Inferring wavelength dependence of AOD and Ångström exponent over a sub-tropical station in South Africa using AERONET data: Influence of meteorology, long-range transport and curvature effect. Sci Total Environ. 2013;461:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.04.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeCanut P, Andreae M, Harris G, Wienhold F, Zenker T. Airborne studies of emissions from savanna fires in southern Africa. 1. Aerosol emissions measured with a laser optical particle counter. [last access: 16 Dec. 2013];J Geophys Res. 1996 101:23615–23630. http://yorkspace.library.yorku.ca/xmlui/handle/10315/4170. [Google Scholar]

- Levy RC, Remer LA, Kleidman RG, Mattoo S, Ichoku C, Kahn R, Eck TF. Global evaluation of the Collection 5 MODIS dark-target aerosol products over land. Atmos Chem Phys. 2010;10:10399–10420. doi: 10.5194/acp-10-10399-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lourens ASM. PhD Thesis. North-West University; Potchefstroom, South Africa: 2012. Air quality in the Johannesburg-Pretoria megacity: its regional influence and identification of parameters that could mitigate pollution. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Zheng X, Chen J. A climatology of aerosol optical depth over China from recent 10 years of MODIS remote sensing data. Int J Climatol. 2014;34:863–870. doi: 10.1002/joc.3728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maenhaut W, Salma I, Cafmeyer J, Annegarn HJ, Andreae MO. Regional atmospheric aerosol composition and sources in the eastern Transvaal, South Africa, and impact of biomass burning. J Geophys Res-Atmos. 1996;101:23631–23650. doi: 10.1029/95JD02930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]