The letter by Garcia et al. (2012) suggests our conclusions that (1) TCRα chain pairing can modify the TCRβ chain binding reaction with MHC and (2) by pairing with a different TCR Vα domain, a TCRβ loop conformation changed and created an altered pMHC binding mode are not supported by the data presented in our recent Immunity article (Stadinski et al., 2011). Below we summarize the question, model system, and the findings of the article to show how we justify these conclusions.

αβTCRs are constructed from a finite set of V gene segments. Despite the limited sequence diversity of CDR1 and CDR2 loops, V(D)J rearrangement and αβTCR chain pairing create receptors that are specific for a particular class of MHC or MHC-like ligands. Remarkably, MHC class-specific TCRs often use the same residues of CDR1 and CDR2 to bind different classes of MHC (Marrack et al., 2008), which raises the following question: if CDR1 and CDR2 loops are able to bind all MHC molecules, how do TCRs distinguish different classes of MHC ligands?

To study the process of MHC ligand specification, we studied IAb-3K-reactive T cells and TCRs isolated from YAe62 TCRβ transgenic mice. One set of TCRs recognized only MHC-II ligands. The second set cross-reacted with β2m-dependent MHC-I and MHC-like ligands including H2-Kb and CD1d. Because all of the TCRs carried the identical TCRβ chain, changes in the TCR-IAb-3K binding reaction could be ascribed to modifications induced by pairing with different TCRα chains. Garcia et al. (2012) suggest that we have not shown that TCRα chain pairing can modify the TCRβ binding reaction with MHC. Our data show that when the identical TCRβ chain is paired with different TCRα chains, (1) different IAbα-helical residues can be required for TCRβ chain binding, (2) different CDR1β and CDR2β residues can be required for binding pMHC, and (3) the CDR3β loop can have a modified conformation, allowing for the CDR3β loop to create different contacts with the pMHC complex. Thus, our experiments showed that TCRβ and IAbα side chains were differentially required by the MHC-specific TCRs for binding depending on the TCRα chain utilized.

In previous structures of Vβ8.2 TCR:pMHC complexes, the CDR1β N29 and CDR2β Y46, Y48, and E54 residues (Arden et al., 1995) (N31, Y48, Y50, and E56 in Garcia et al. [2012]) form a hydrogen bonding network with the IAα chain residues K39, Q57, and Q61 (Feng et al., 2007; Reinherz et al., 1999). Contacts between these CDR2β and IAbα chain residues occur in the YAe62-IAb-3K structure as well (Dai et al., 2008), which led to a hypothesis for the existence of a conserved, pairwise Vβ8.2-IA interaction motif, termed a “codon” (Feng et al., 2007; Garcia et al., 2009). These CDR2β residues, most notably Y46 and Y48, are also important for thymic selection of T cells carrying the DO TCRβ chain (Scott-Browne et al., 2009). However, other than a study of two TCRs binding IAb-3K (of which the YAe62 TCR was one) (Huseby et al., 2006), the contribution of the MHC IA helical residues for binding Vβ8.2 TCRs has not been directly evaluated.

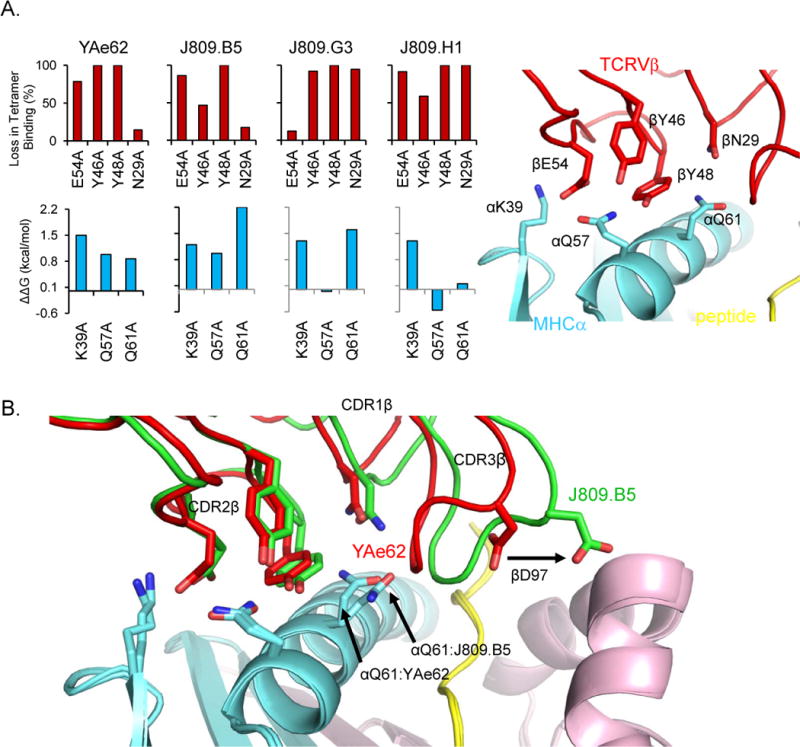

We found that TCRs carrying the YAe62β chain had variable requirements for CDR1β, CDR2β, and IAbα residues. The variability was most apparent for the IAbα side chains. The YAe62 TCR and the J809.B5 TCR each use all six CDR2β and IAbα side chains of the proposed Vβ8.2-IA codon for binding IAb-3K, and neither require the CDR1β N29 residue (Figure S1A available online). The J809.B5 TCR differs from YAe62 mostly in the role of IAbα Q61, which is more important for the J809.B5 TCR (Q61A completely eliminates binding, Kd > 250 μM) than for YAe62 TCR (Q61A changes Kd from 13 μM to 52 μM). In contrast to the YAe62 and J809.B5 TCRs, the J809.G3 and J809.H1 TCRs require different TCRβ and IAb side chains to bind IAb-3K. The J809.G3 TCR uses CDR1β N29, two of the three CDR2β side chains, and two of the three IAbα side chains for binding. The J809.H1 TCR uses CDR1β N29 and all three CDR2β residues, yet it does not require either IAbα Q57 or Q61 for binding. In addition, the pattern of side chain requirements used by the J809.G3 and J809.H1 TCRs indicates that the same TCR Vβ8.2 side chains can be used to bind IAb-3K differently. For example, the J809.G3 TCR requires IAbα K39, yet does not require its predicted binding partner, CDR2β E54, and the J809.H1 TCR requires CDR1β N29, yet does not require IAbα Q61. In Stadinski et al. (2011), we noted that these data did not appear to be consistent with predicted binding patterns of the Vβ8.2-IA codon model. These results argue that Vβ8.2 TCRs can use CDR1β and CDR2β residues to bind IA MHC proteins with an array of nonconserved interactions, which can be influenced by the paired TCR chain.

The TCR-MHC coevolution model described in the letter by Garcia et al. (2012) suggests that the Vβ8.2 CDR2β residue Y48 is of central importance and that evolution has selected for it because of its “flexibility,” i.e., the ability to make a variety of chemical bonds. This flexibility will allow it and other germline-encoded TCR residues to adopt “different rotamer” and “different pairings of specific amino acids” when binding MHC ligands. Our data are consistent with an important role for CDR2β Y48, which was utilized by each of the TCRs studied regardless of whether the MHC IAb αQ57 or αQ61 residue side chains were involved.

Can we conclude that as a result of pairing with a different TCR Vα domain, a TCRβ loop conformation changed and created an altered pMHC binding mode? We show that when the J809.B5 TCR is bound to IAb-3K, the CDR3β loop has undergone a conformational change relative to that same loop in the YAe62 TCR bound to IAb-3K (Figure S1B). The YAe62 CDR3β loop (red) kinks sharply, placing the tight hairpin turn above and between the IAbβ chain helix and the bound 3K peptide. In contrast, the J809.B5 CDR3β loop (green) is more open, kinks less tightly, and extends much closer toward the IAbβ chain. The conformational change creates additional TCR-MHC contacts and additional buried surface area (BSA) involving the peptide and IAbβ chain (see Figure 5 in Stadinski et al., 2011). Because both complexes contain the identical TCRβ, MHC, and peptide residues, this clearly demonstrates that TCRα chain pairings can result in TCRs in which the CDR3β loop is in a different conformation.

As noted in Garcia et al. (2012) there is not a large rmsd between the CDR1β and CDR2β loops of the J809.B5 and YAe62 TCRs, relative to other examples of different TCR Vβs binding different pMHC complexes. This is not surprising considering that the J809.B5 and YAe62 using the same CDR1β and CDR2β sequences are identical, are binding the same ligand, and use the same CDR2β and IA side chains for binding. The J809.B5 TCR-IAb-3K complex does have a rotamer change at IAbαQ61 allowing for different interactions with TCRβ residues (see Figure S5 in Stadinski et al., 2011). Although the structural changes are small, they help explain why the J809.B5 TCR has a large increase in the binding requirement for the IAbα Q61 side chain. Collectively, the different CDR3β conformations, the altered TCRβ-pMHC contacts and buried surface area, and the TCRβ structural and energetic changes near the IAbα Q61 residue led us to conclude that the binding modes of the J809.B5 and YAe62 TCRβ chains were different and due to pairing with different TCRα chains.

How do TCRs generate self-tolerance and specificity for unique MHC ligands? Relative to the self-reactive YAe62 TCR, the self-tolerant J809.B5 TCR has increased CDR3 contacts and creates more buried surface with the peptide and has changed how the TCRβ chains interacts with the pMHC. These differences are clearly observed in the biophysical data (see Figures 3–6, S3, and S4 in Stadinski et al., 2011). Although these overall structural changes may seem “minor,” biologically they represent the differences between a highly self-reactive, MHC class-cross-reactive TCR and a self-tolerant, MHC class-specific TCR. The additional self-tolerant, MHC-specific TCRs studied in Stadinski et al. (2011) also showed clear changes in TCR-MHC interactions and an increased requirement for peptide residues. The ability of αβTCR chain pairing to modify TCR interactions with both MHC and peptide highlights a mechanism whereby T cell selection can tailor TCR recognition to the MHC present in the host.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1. Alteration of TCRβ interactions to IAb-3K.

(A) The YAe62, J809.B5, J809.G3 and J809.H1 TCRs, and TCRs containing alanine substitutions at βE54 βY46 βY48 or βN29 were expressed on insect cells and stained with IAb-3K tetramers (upper panel). Data are percent loss in binding as compared to the wild-type TCR. The ΔΔG values of YAe62, J809.B5, J809.G3 and J809.H1 TCRs binding IAb-3K containing alanine substitutions at IAb αK39, αQ57 or αQ61 as calculated from SPR measurements (αQ57 and αQ61) or TCR multimer staining (αK39) (lower panel). Positions of YAe62 (red) CDR2β residues βE54, βY46, βY48 and CDR1β residue βN29 and IAb α (cyan) side chains αK39, αQ57, αQ61 in YAe62:IAb-3K complex (right panel).

(B) Overlay of J809.B5 (green) and YAe62 (red) TCRβ chains binding IAb-3K. IAbα chain (cyan) Iabβ chain (magenta) and the 3K peptide (yellow) are shown, while the TCRα chains were removed for clarity. The alternate rotamer of IAb αQ61 in the J809.B5:IAb-3K complex versus the YAe62:IAb-3K complex is labeled. Alteration of CDR3 loop structure is highlighted by the CDR3β residue D97, which forms interactions with the IAbβ chain in the J809.B5 TCR:IAb-3K complex.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes one figure and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.019.

References

- Arden B, Clark SP, Kabelitz D, Mak TW. Immunogenetics. 1995;42:501–530. doi: 10.1007/BF00172177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai S, Huseby ES, Rubtsova K, Scott-Browne J, Crawford F, Macdonald WA, Marrack P, Kappler JW. Immunity. 2008;28:324–334. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng D, Bond CJ, Ely LK, Maynard J, Garcia KC. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:975–983. doi: 10.1038/ni1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia KC, Adams JJ, Feng D, Ely LK. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:143–147. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia KC, Gapin L, Adams J, Birnbaum M, Scott-Browne J, Kappler J, Marrack P. Immunity. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.018. Published online June 14, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huseby ES, Crawford F, White J, Marrack P, Kappler JW. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1191–1199. doi: 10.1038/ni1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrack P, Scott-Browne JP, Dai S, Gapin L, Kappler JW. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:171–203. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz EL, Tan K, Tang L, Kern P, Liu J, Xiong Y, Hussey RE, Smolyar A, Hare B, Zhang R, et al. Science. 1999;286:1913–1921. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Browne JP, White J, Kappler JW, Gapin L, Marrack P. Nature. 2009;458:1043–1046. doi: 10.1038/nature07812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadinski BD, Trenh P, Smith RL, Bautista B, Huseby PG, Li G, Stern LJ, Huseby ES. Immunity. 2011;35:694–704. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.