Abstract

Phytoestrogens (PEs) are non-steroidal ligands which regulate the expression of number of estrogen receptor-dependent genes responsible for a variety of biological processes. Deciphering the molecular mechanism of action of these compounds is of great importance because it would increase our understanding of the role(s) these bioactive chemicals play in prevention and treatment of estrogen-based diseases. In this study, we applied suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH) to identify genes that are regulated by phytoestrogens through either the classic nuclear-based estrogen receptor or membrane-based estrogen receptor pathways. Suppression Subtractive Hybridization, using mRNA from genistein (GE) treated MCF-7 cells as testers, resulted in a significant increase in GNB1 mRNA expression levels as compared with 10 nM 17-β estradiol or the no treatment control. GNB1 mRNA expression was upregulated 2- to 5-fold following exposure to 100.0 nM genistein. Similarly, GNB1 protein expression was up regulated 12- to 14-fold. Genistein regulation of GNB1 was estrogen receptor-dependent, in the presence of the antiestrogen ICI-182,780, both GNB1 mRNA and protein expression were inhibited. Analysis of the GNB1 promoter using ChIP assay showed a phytoestrogen-dependent association of estrogen receptor α (ERα) and β (ERβ) to the GNB1 promoter. This association was specific for ERα since association was not observed when the cells were co-incubated with genistein and the ERα antagonist, ICI. Our data demonstrate that the levels of G-protein, beta-1 subunit are regulated by phytoestrogens through an estrogen receptor pathway and further suggest that phytoestrogens may control the ratio of α-subunit to β/γ-subunits of the G-protein complex in cells.

Keywords: GNB1, Phytoestrogens

INTRODUCTION

Estrogens are involved in the growth, development, and maintenance of a number of tissues. The physiological effects of estrogens are mediated by two different ligand-inducible nuclear transcription factors, ERα and ERβ. Estrogens bind to the ligand-binding domain of the ERs and initiate a series of molecular events culminating in the transcriptional activation or repression of target genes (Aranda and Pascual, 2001; Beekman et al., 1993; Cavailles et al., 1994; Gorski et al., 1993; Matthews et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2007). Transcriptional regulation of genes by the ER arises from direct genomic or nongenomic interaction (Bjornstrom and Sjoberg, 2005). Both the genomic and non-genomic effects of ER ligands are dependent on the nature of the target cell and the associated ligand (Bjornstrom and Sjoberg, 2005). Genomic interaction involves binding of ligands to ERα or ERβ and interaction of the receptor-ligand complex with components of the transcription machinery (Colgan et al., 1993; Robyr et al., 2000). Nongenomic transcriptional regulation involves binding of ligands to ERα, ERβ or membrane-bound ER (mER), resulting in activation of a variety of intracellular secondary messenger signaling systems (Razandi et al., 2004; Song et al., 2006). The mERs are responsible for the rapid effects of 17-β estradiol that occur within seconds to minutes after induction (Filardo, 2002; Toran-Allerand, 2004) and involve a variety of intracellular secondary messenger signaling pathways. 17-β estradiol (E2), the major type of estrogen in humans, rapidly increases the concentration of intracellular secondary messengers, including calcium (Benten et al., 2001; Lieberherr et al., 1993) and cAMP (Farhat et al., 1996a; Farhat et al., 1996b), via activation of Gβγ subunits (Le Mellay et al., 1999) or Gα subunits (Doolan and Harvey, 2003), phospholipase C (Le Mellay et al., 1997), protein kinase C (Ansonoff and Etgen, 1998; Sylvia et al., 2001), the MAPK pathway (Hennessy et al., 2005; Migliaccio et al., 1996; Nethrapalli et al., 2005), or transcription factors such as CREB (Wade and Dorsa, 2003).

Modulation of ER-responsive genes by ERα, ERβ or the ER through their cognate ligand, estradiol, is well studied; however, the transcriptional activation of the ER responsive genes by non-steroidal estrogens such as the phytoestrogen is less well-known. Phytoestrogens (PEs) are a group of non-steroidal biologically active ligands with chemical structure similar to the steroid hormone 17-β estradiol. These compounds are suspected of antagonizing the estrogenic effects of the endogenous estrogen, 17-β estradiol (E2). The biological effects of PEs are well documented in humans and animals (Adlercreutz et al., 1993; Arai et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2002; Knight and Eden, 1996; Komori et al., 1993; Messina et al., 1994). Several studies have suggested that PEs may function like 17-β estradiol in lowering the risk of cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis in post-menopausal women (Horowitz, 1993; Mei et al., 2001; Rodan and Martin, 2000). Researchers, using urine PE excretion as an index of PE exposure, have found a strong correlation between PE in the diet and a lower incidence of breast and prostate cancers (Barnes and Peterson, 1995; Barnes et al., 1995; Horowitz, 1993; Messina et al., 1994; Musey et al., 1995). Furthermore, epidemiological studies demonstrate that populations with a high content of soya (soya being the major source of PEs) in their diet exhibit a low incidence of breast and prostate cancers (Brawley and Barnes, 2001; Messina et al., 1994). PEs can bind to ER in vitro and exert estrogenic effects in vivo (Santell et al., 1997). Although the biochemical mechanism responsible for PE action is unknown, it is generally agreed that the beneficial effects of PEs are mediated through interaction with the ERα, ERβ or mER.

The biological effects of PEs in mammalian cells are 2-fold. First, ingestion of large quantities of these compounds offer protection against development of breast and prostate cancers. Second, their estrogenic properties may produce adverse effects during critical developmental periods or enhance estrogen dependent breast or prostate cancer (Ardies and Dees, 1998; Dees et al., 1997; Hedelin et al., 2006a; Hedelin et al., 2006b; Hsieh et al., 1998). Numerous studies have documented the stimulation or inhibition of estrogen responsive genes by phytoestrogens (Brownson et al., 2002; Hsieh et al., 1998; Hyder et al., 1999). For example, Lamon et al. have demonstrated that both GE and 17-β estradiol activate apoA-1 gene expression through a common pathway (Lamon-Fava and Micherone, 2004). Furthermore, the mechanism of transcriptional activation or repression resulting from these compounds binding to the different forms of estrogen receptor has been suggested to be similar, if not identical, to that of 17-β estradiol. Using RAW264.7, a murine monocyte cell line which expresses ERα but not ERβ, Garcia et al. demonstrated that repression of the RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation is accomplished by both phytoestrogens and 17-β estradiol binding to ERα (Garcia Palacios et al., 2005).

The current scientific consensus is that the outcome from increased phytoestrogen intake is unpredictable partly due to a poor understanding of its mechanism of action in breast and prostate cells. The estrogenic properties of PEs have been measured using a variety of assays and animal models (Tang and Adams, 1980; Whitten et al., 1994). Admittedly, the endpoints of these assays are good indicators of PE estrogenicity. However, these assays generally measure multi-step processes and do not provide information concerning the initial effects of PEs. Furthermore, no methodology is available to measure the direct effect of PEs on target genes, independent of estrogenic activity. In this study, we have applied the SSH technique to isolate unique genes that are differentially regulated by PE and or by 17-β estradiol in ER-positive MCF-7 cells. We have identified several biological markers that could be used to assess the functional and mechanistic action of PEs. The genes identified perform a variety of biological functions ranging from nucleic acid metabolism to signal transduction. Notably, we demonstrated that the expression of the beta subunit of the G protein–coupled receptor gene (GNB1) is mediated through a phytoestrogen-estrogen receptor mechanism.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Reagents

Coumestrol (CO) was purchased from ACROS Organics (New Jersey), and Zearalenone (ZE), Genistein (GE), 17-β estradiol (E2) and R,R-THC were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). ICI 182,780(ICI) was purchased from Tocris Cookson Ltd. (Ballwin, MO). A 1.0 mM stock solution of all compounds was made in ethanol. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Hyclone (Logan, UT). Insulin, pencillin-streptomycin solution, and trypsin/EDTA solution were all purchased from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY).

Cells and Cell Culture

MCF-7 cells obtained from the American Type Culture Collection were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 and maintained in phenol red-free DMEM, supplemented with 10% FBS, insulin (1.0 ng/mL), 0.2 mM glutamine, 100U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. Cells were maintained in a water-jacketed incubator and were passaged when they reached 80%-confluence using a Trypsin/EDTA solution.

Pharmacological treatments

For experiments involving and gene induction studies, cells were grown in test media (phenol red-free DMEM media containing 5% FBS that was stripped three times with dextran coated charcoal) for seven days. For gene induction studies, cells were plated at a density of 107cell/well, in 20 cm plates, allowed to attach, and treated with corresponding PEs for 24 h.

Isolation of RNA

Total RNA was isolated by the acid guanidine isothiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction method (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 1987) using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Total RNA (100–150 μg) was treated with RNase-free DNase I (1 U/μg), extracted with phenol/CHCl3, and precipitated with ethanol in the presence of 3M NaC2H3O2. The resulting RNA was resuspended in diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) treated water and used in standard one-step RT-PCR, subtractive hybridization, Northern analysis and poly A+ RNA selection. Poly A+ RNA was isolated by Oligotex mRNA Batch protocol (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Preparation of Tester and Driver for PCR-Based Dual Subtractive Hybridization

Suppresion Subtractive Hybridization was performed with the PCR-Select Subtraction Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, two subtractions were performed using either GE-induced mRNA or the first differential product (DP1) cDNA as the tester. Two drivers were also prepared, one from control mRNA (from uninduced MCF-7 cells) and the other from 17-β E2-induced mRNA. Both tester and driver DNA were prepared by reverse-transcribing 5 μg of DNase I-treated mRNA into cDNA using avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase, and 10 μM of cDNA synthesis primer (Table 1). For DP1, 2 μg each of tester and driver DNA were digested to completion with 15 U of Rsa I (New England Biolabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA) for 2 h at 37°C following which the samples were extracted with phenol, precipitated with ethanol, and resuspended in water at a final concentration of 300 ng/μl. Two aliquots of the tester DNA (100 ng each) were ligated separately to two aliquots of the forward adaptor (F1 primer) or the reverse adaptor (R1 primer) (Table 1), at 16°C overnight, using 400 U of T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs, Inc.). After ligation, the enzyme was inactivated using 1 μl of EDTA/glycogen mixture and the sample was stored at −20°C until used.

Table I.

Sequences of primers and probes used in Suppression Subtractive Hybridization, QRT-PCR and ChIP Assay

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence | Applicationc |

|---|---|---|

| cDNA synthesis Primera | 5′-TTTTGTACAAGCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′ | SSH |

| SSH-Adaptor 1b | 5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTCGAGCGGCCGCCCGGGCAGGT-3′ 3′-GGCCCGTCCA-5′ |

SSH |

| SSH-Adaptor 2Rb | 5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCAGCGTGGTCGCGGCCGAGGT-3′ 3′-GCCGGCTCCA-5′ |

SSH |

| PCR primer 1 | 5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC-3′ | SSH |

| Nested PCR Primer 1 | 5′-TCGAGCGGCCGCCCGGGCAGGT-3′ | SSH |

| Nested PCR Primer 2R | 5′-AGCGTGGTCGCGGCCGAGGT-3′ | SSH |

| GAPDH 5′Primer | 5′-CCATGGAGAAGGCTGGGG -3′ | QRT-PCR |

| GAPDH 3′ Primer | 5′-CAAAGTTGTCATGGATGACC-3′ | QRT-PCR |

| GNB1 5′ Primer | 5′-AGGGGTAAGGGAGCAGAG-3′ | QRT-PCR |

| GNB1 3′ Primer | 5′-GCAGCAGTAGTGGCTTCTCC-3′ | QRT-PCR |

| GNB1 Promoter Primer A | 5′-ACGGTTACCCAACCTTACCC-3′ | ChIP Assay |

| GNB1 Promoter Primer B | 5′-GTGTCCGAGCGGCTTAAAG-3′ | ChIP Assay |

| GNB1 Promoter Negative Primer A | 5′-AAAAAGGCTTCCATGAAGATGA-3′ | ChIP Assay |

| GNB1 Promoter Negative Primer B | 5′-GGAGTGGGGAGATCTGTTGA-3′ | ChIP Assay |

Primer set used for the construction of suppressive subtractive library and conformation of gene expression.

SSH primers and primer sequence were provided in the Clontech PCR-Select™ cDNA subtraction kit.

QRT-PCR and ChIP assay primers were designed using Primer3 software program.

Subtractive Hybridization-DP1

Control driver DNA (450 ng) was combined separately with 15 ng of F1 and R1 adaptor-ligated GE-induced tester cDNA (30:1 ratio) and 1μL of 4X hybridization buffer (2.5 M NaCl/250 mM HEPES, pH 8.3/1 mM EDTA) and the samples were overlaid with mineral oil. The samples were denatured (1.5 min, 98°C) and allowed to anneal for 8 hr at 68°C. Following hybridization, both samples were combined and 300 ng of fresh, heat-denatured driver cDNA was added and a second round of hybridization performed for 12 h at 68°C without the denaturation (1.5 min, 98°C) step. The final hybridized product (DP1) was diluted to 210 μl with dilution buffer (50 mM NaCl/5 mM HEPES, pH 8.3/0.2 mM EDTA), heated at 68°C for 7 min, and stored at −20°C.

The DP1 product was amplified in two sequential PCR steps using different PCR primers. Diluted DP1 DNA (1 μL) was first amplified linearly with 10 μM primer P1 (Table 1) in a final volume of 25 μL, using the Advantage cDNA PCR Core Kit (Clontech), and the following thermal cyclers: 1 cycle of 94°C, 25 sec and then 30 cycles of 94°C, 10 sec; 66°C, 30 sec; 72°C, 1.5 min. The amplified products were then diluted ten-fold in water and 1 μl of the diluted sample was differentially amplified in a second PCR reaction for 12 cycles of 94°C, 10 sec; 68°C, 30 sec; and 72°C, 1.5 min with 10 uM of NP1 and NP2 primers (Table 1). The PCR-amplified DP1 cDNAs were ligated into pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega Corp., Madison WI, USA), and the ligated DNA clones were transformed and amplified into JM109 competent cells (Promega Corp.). The second differential product (DP2) was prepared by digesting 2 μg of DP1 cDNA with Rsa I in order to generate tester 2. This tester was subjected to hybridization and PCR amplification as described for tester 1 above. The resulting DP2 cDNA was also ligated into pGEM-T Easy vector and screened for differentially expressed genes.

Screening of DP1 and DP2 cDNA Library by Reverse Northern

Seven-hundred individual DP2 cDNA clones were grown in LB-ampicillin in separate wells of seven, 96-well cell culture plates. Four sets of membrane arrays were prepared by spotting 50 μL of the culture on a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) using a 96-well vacuum manifold. The membrane was denatured with 100 μL of denaturation solution (1.5 M NaCl/0.5 M NaOH), neutralized with 100 μL of neutralizing solution (1.5 M NaCl/0.5 M Tris-Cl, pH 7.0) and the resulting DNA was cross-linked to the membrane using Bio-Rad GS Gene linker (Bio-Rad Laboratory, Inc., Hercules, CA). Each membrane was probed with 32P-labeled cDNAs prepared by reverse transcription of total RNA isolated from MCF-7 cells induced with 100 nM GE or 10 nM 17-β E2. The membrane arrays were hybridized with 2 × 106 cpm/mL of probe overnight at 50°C in a Hybaid rotisserie hybridization oven (Labnet, Woodbridge, NJ, USA) using ExpressHyb hybridization solution (Clontech). Membranes were washed with 1X hybridization buffer (Molecular Research Center Inc., Cincinnati, OH) at 50°C for 1 h, followed by 2X SSC/0.5% SDS at 50°C for 30 min.

Preparation of cDNA Probe

Both 32P-labeled cDNA probes (GE-induced cDNA probe, 17-β E2-induced cDNA probe) were prepared according to the procedures of Ramanathan et al. (Ramanathan and Gray, 2003). Briefly, twenty micrograms of total RNA was reverse transcribed using 2 μL of anchored Oligo (dT) primers (2.5 μg/μL). The RNA was heated at 70°C for 5 min and quenched on ice for 2 min. Primer mixture (50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.3), 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, 0.5 mM dATP, 0.5 mM dGTP, 0.5 mM dTTP, 1μL of RNase inhibitor (Invitrogen, 40U/μL)), 100 mCi dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol, Amersham Pharmacia), and 800 U of Superscript RT II (Invitrogen) were then added for a final reaction volume of 50 μL. The reaction mixture was incubated at 46°C for 2–3 hrs. The unincorporated [32P] CTP was removed by spinning the sample in a Sephadex G-50 spin column (Amersham Pharmacia).

Western blot analysis

The total protein was extracted from MCF-7 cells in RIPA lysis buffer using two 10 sec cycles of sonication using a Microson Sonicator (Misonix, Inc., Farmingdale, NY, USA). Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford reagent protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratory, Inc.). The total protein (20 μg) was fractionated using a precast 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The fractionated protein was transferred to an Immobilon Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0/150 mM NaCl/0.1% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature and immunoblotted with a 1:1000 dilution of 0.5 μg/mL rabbit anti-human GNB1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or it was blocked with 5% BSA in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature and immunoblotted with a 1:1000 dilution of 0.5 μg/mL anti-GAPDH antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). The blots were washed three times with TBST buffer and GNB1 protein was detected using a 1:10,000 dilution of goat anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase labeled antibody (Kierkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD) at room temperature for 1 h. The bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The immuno-reactive signal was captured using an Alpha Innotech Fluorchem HD 9900 equipped with a CDD camera and the images were analyzed with the AlphaEaseFC software.

Quantitative real time RT-PCR

The total RNA (25 ng) isolated from MCF-7 cells induced with 100 nM of the phytoestrogens in the absence or presence of the antiestrogen ICI 182,780 was amplified using the Sigma SYBR Green Quantitation RT-PCR kit. PCR was performed in a 50 μL final volume containing 100 ng of gene specific primer, 1X one-step RT-PCR master mix and 5 U of enzyme. The GNB1 gene-specific primers were designed from a 500 bp EcoR I digested cDNA fragment using Primer 3 software (Table 1). One-step RT-PCR analysis was conducted on an ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detection System with universal reaction temperatures as follows: The RT reaction was incubated at 50°C for 30 min to allow cDNA synthesis and terminated by heating for 2.0 min at 95°C. The resulting cDNA was then PCR amplified for 40 cycles consisting of 94°C for 15 sec, and 60°C for 1 minute.

The relative level of expression of each gene was determined using the relative 2ΔΔCt expression method as described in detail in the ABI PRISM Sequence Detection System User Bulletin 2 (Biosystem, 2001a). (Biosystem, 2001b)(Biosystem, 2001b)After the linear range of amplification (threshold cycle, Ct) was determined for the genes of interest, the gene expression was normalized against an endogenous GADPH control and then against the untreated control sample, which served as the calibrator. The value of the relative level of expression for the gene of interest represents two independent inductions performed in triplicate.

RNA extraction and Northern blot analysis

Total RNA was obtained from cells treated with 0–100 nM GE, or 10 nM 17-β E2, in the presence or absence of 50-fold ICI-182,780 for 24 hours, using 1.0 mL of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). The RNA pellet was re-suspended in water, treated with DNase I, re-precipitated and quantified by reading the 260/280 nm absorbance on a Bio-Rad Spec3000 spectrophotometer. Twenty micrograms of total RNA per lane was fractionated on a 1.2% agarose-formaldehyde denaturing gel. The fractionated RNA was then transferred to a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia) by upward capillary blotting, and then UV cross-linked using Bio-Rad GS Gene linker. The DNA probe, a 500 bp EcoR I cDNA fragment of GNB1 used in Northern analysis, was generated from a 1.3 kbp recombinant clone in a pGEM-T Easy Vector. The probe was 32P-labeled by random priming using the Promega Prime-a-Gene kit (Ramanathan and Gray, 2003). The unincorporated [32P] CTP was removed by spinning the sample in a Sephadex G-50 spin column (Amersham Pharmacia). Membranes were hybridized with 1.0–3.0 × 106 cpm/mL of probe overnight at 50°C in a Hybaid rotisserie hybridization oven (Labnet) using ExpressHyb hybridization solution (Clontech). Membranes were washed with 1X hybridization buffer (Molecular Research Center Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA) at 50°C for 1 h, followed by 2X SSC/0.5% SDS at 50°C for 30 min. To verify equal loading of RNA, the membrane was stripped (boiling solution of 0.5% SDS in 40 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10% glycerol and 2.0 mM EDTA) and re-hybridized with a 350 bp fragment of the GAPDH gene as the probe. Hybridized fragments were quantified on Cyclone PhosphoImager (Packard, Meriden, CT) using OptiQuant Image analysis software. All Northern analyses were repeated multiple times (N ≥ 3) with separate blot/RNA preparations. Values from each blot were normalized against the GAPDH gene.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

The ChIP assay was performed as described by Shang et al (Shang et al., 2000) with slight modifications. Briefly, MCF-7 cells were grown in 20 cm plates for 7 days in phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 5% DCC-treated serum. Cells with a density of 1 × 107 cells/plate were treated with 100 nM phytoestrogens (GE and CO) in the absence or presence of 1 μM ICI for 24 hr. The protein-DNA complexes were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min, followed by quenching with 125 mM glycine. The cells were then washed with PBS, harvested by scraping, resuspended in lysis buffer (5 mM PIPES (2-[4-(2-sulfoethyl) piperazin-1-yl] ethanesulfonic acid) (KOH), pH 8.0/85 mM KCl/0.5% NP-40) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) and finally spun at 5 K for 10 min. After lysis the nuclei were resuspended in 200 μL of nuclear lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.1/10 mM EDTA/1% SDS) and sonicated ten times for 10 sec each using a Microson Sonicator (Misonix, Inc.). The 100 μg of sonicated chromatin was pre-cleared with protein G-agarose, and then incubated with 5 μg of ER-712 antibody at 4°C overnight. Following overnight incubation, 25 μL of protein G magnetic beads was added to the sample and incubated under gentle agitation for 6 hr at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and the magnetic beads were successively washed in 0.5 mL of low salt buffer (0.1% SDS/1% Triton X-100/2 mM EDTA/20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1/150 mM NaCl), followed by 0.5 mL high salt buffer (0.1% SDS/1% Triton X-100/2 mM EDTA/20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1/500 mM NaCl), then 0.5 mL LiCl buffer (0.25 M LiCl/1% IGEPAL-CA630 (Octylphenoxy polyethoxyethanol Octylphenyl-polyethylene glycol)/1% deoxycholic acid/1 mM EDTA/10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1) and twice with 0.5 mL TE wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0/1 mM EDTA). The protein/DNA complexes were eluted in 50 μL elution buffer (1% SDS/0.1 M NaHCO3), and the precipitated complexes were analyzed by western blotting and PCR. For PCR analysis, the DNA/protein crosslinking from immunoprecipitated nuclei or unprocessed nuclei was reversed by incubation at 65°C for 6 hrs, and then 250 ng of purified DNA was PCR-amplified with PCR primers directed at different regions of the GNB1 promoter (Table 1). All samples were amplified with 35 cycles of 94°C, 30 sec; 55°C, 30 sec; and 72°C, 30 sec, followed by 1 cycle of 95°C, 30 sec; 55°C, 30 sec; and 72°C, 2 min. Equal amounts of PCR products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

RESULTS

Identification of classical and non-classical estrogen-regulated genes induced by phytoestrogen

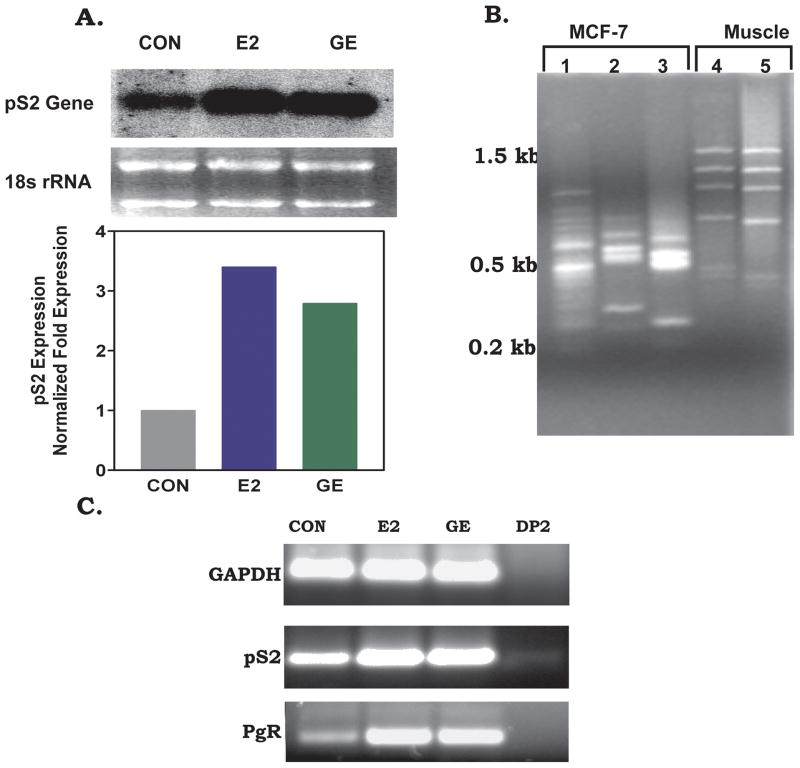

Phytoestrogen has been shown to modulate a variety of biological processes, many of which are hormone dependent. Previous studies in our laboratory and others have reported the isolation of phytoestrogen-regulated genes from different cell lines (Hsu et al., 1999; Ramanathan and Gray, 2003). The drawback with these studies was that the genes isolated were not regulated specifically by phytoestrogen and thus are not suited as a model to examine the mechanism of phytoestrogen-dependent transcription. To circumvent this problem, we applied a PCR-based dual-suppressive subtractive hybridization (SSH) selection, a process aimed at removing most if not all housekeeping genes and genes that are inducible by 17-β estradiol. Two differential products (DP) were generated from mRNA populations that were induced with either 10nM 17-β estradiol (E2) or 100nM Genistein (GE) (Fig. 1A). The first subtractive hybridization was performed using mRNA isolated from MCF-7 cells induced with 100 nM GE as tester-1 against control mRNA sample as driver-1. The differentially expressed cDNA products (DP1s) obtained from this subtraction (Fig. 1B, lane 1) ranged from 250 bp to 1000 bp, a product size range that is similar to an SSH control sample (Fig. 1B, lanes 4 and 5). Since GE is known to stimulate estrogen-responsive genes (Fig. 1A), our DP1 would represent a population that contains both putative phytoestrogen and estrogen-regulated genes. To obtain a more phytoestrogen specific differential product, the DP1 cDNA was used as tester in a second subtraction along with cDNA prepared from MCF-7 cells induced with 10 nM 17-βE2 as driver. The product resulting from this subtraction (second differential product, DP2) was decreased in complexity as evident in the number of low molecular weight cDNA products observed (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 and 3). We confirmed the authenticity of the DP1 and DP2 subtracted cDNA products by monitoring the depletion of genes that were common to both populations and genes that were regulated by 17-β estradiol. An analysis of DP1 and DP2 (Fig. 1C) indicates that the pS2 gene, a breast cancer specific marker, and the progesterone receptor gene (PgR), an 17-β estradiol inducible gene, were both depleted from the DP2 population. As expected, we observed that the housekeeping gene, glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), was maximally depleted from the DP1 library as indicated by PCR (data not shown). There were residual levels of the pS2 gene (reduced approximately 1000 fold) following the second subtractive hybridization as compared to the un-subtracted cDNA (Fig. 1C, data not shown). The presence of residual levels of pS2 gene in the DP2 population may be the result of GE stimulation of these genes in MCF-7 cells (Allred et al., 2001; Hsieh et al., 1998; van Meeuwen et al., 2007) (Fig. 1A). Taken together, our dual SSH approaches resulted in a population of cDNA (DP2) that contained gene products that are induced two- to three-fold by GE.

Figure I. Identification of differentially expressed sequences by suppression subtractive hybridization.

MCF-7 cells were grown in the presence and absence of 100 nM GE or 10 nM 17-β E2 for 24 h. DNase I-treated mRNA obtained from these cells was subjected to PCR-select subtractive hybridization as described in Materials and Methods. (A) pS2 expression following exposure to GE or 17-β E2. (B) Agarose gel of differential PCR products (DP) obtained after subtractive hybridization. Lane 1, DP1 (control verses GE); Lane 2, DP2 (DP1 verses 17-β E2); Lane 3 amplification of DP2 with nested PCR primers; Lane 4, SSH Control, human skeletal muscle cDNA spiked with plasmid DNA as tester; Lane 5, amplification of SSH control with nested PCR primer. (C) PCR analysis of subtraction efficiency. PCR was performed on driver (CON or 17-β E2), unsubtracted tester (GE), and subtracted product (DP2) using GAPDH, pS2 or PgR specific primers.

Genistein–specific DP2 cDNA library contains genes that are regulated through classical and non-classical estrogen receptor pathway

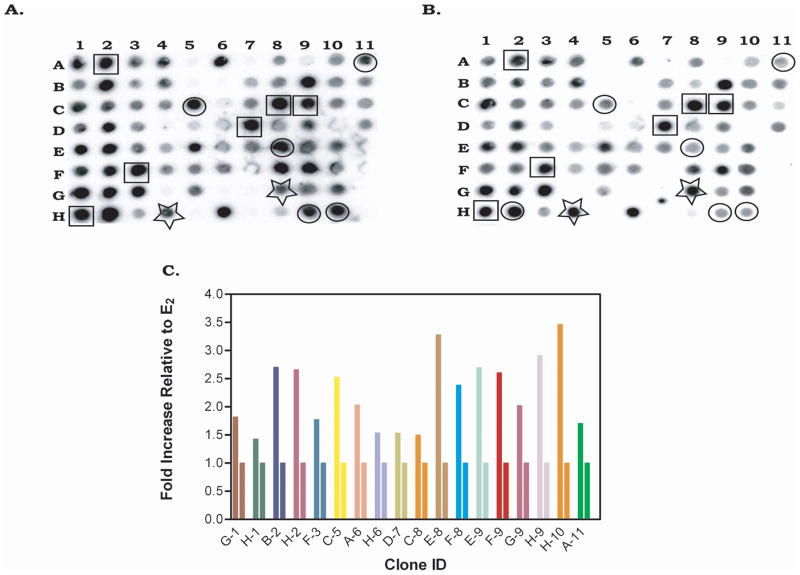

Subtractive hybridization is a powerful technique that exemplifies differences between genes present in two different populations. However, it does not provide quantitative information on the degree of expression of these genes in the resulting subtractive populations. Therefore, we used reverse Northern blotting to determine whether any of the genes present in our DP2 library were in fact inducible by GE. Seven hundred individual DP2 clones were immobilized onto Hybond Nylon membranes. These clones were screened using radio labeled cDNA derived from RNA taken from MCF-7 cells induced with 100 nM GE or 10 nM 17-β E2. Figure 2 represents two typical blots containing 80 individual clones that were hybridized with GE-induced cDNA (Fig. 2A) or 17-β E2-induced cDNA (Fig. 2B). Expression screening of our DP2 cDNA library identified three distinct expression phenotypes. Thirty-two percent of the genes present in the DP2 library displayed dual regulation by both GE and 17-β E2 (Fig. 2A and 2B, squares). At the same time, 4–5% of the genes in the library were induced specifically by GE (Fig. 2A and 2B, circles). Less than 1% was induced by 17-β estradiol (Fig. 2A and 2B, stars), and the remaining 62% did not show any change in expression by reverse Northern. Our DP2 library was depleted of 17-β estradiol-responsive genes (Fig. 1). However, we observed a high number of dual-regulated genes in the library, suggesting that some genes may possess cryptic levels of induction in the presence of 17-β E2. Due to the presence of cryptic levels of induction of certain genes present in the library, we defined the GE-specific genes by using the relative expression level in the presence of GE, normalized to the expression induced by 17-β estradiol (Fig. 2C). Those genes which possess induction levels greater than 2-fold were chosen as GE-responsive genes and further characterized by sequencing.

Figure II. Quantification of differentially expressed genes via reverse Northern blot analysis.

Differential products (DP2) obtained from SSH between DP1 and 17-β E2 were cloned into a pGEM-T cloning vector and several individual clones were dot-blotted onto nylon membranes. GE differential expression clones (A) or 17-β E2 differential expression clones (B) were identified by probing the blot with equal amounts of 32P cDNA prepared from reverse transcribed RNA obtained from MCF-7 cells treated with 100 nM GE or 10 nM 17-β E2 as described in Materials and Methods. Circles represent those genes that are regulated by GE, stars represent genes that are regulated by 17-β E2 and squares represent genes that show dual regulation by both GE and 17-β E2. (C) Fold expression of GE responsive genes relative to 17-β E2. The signal on the autoradiograph in blot A and blot B was quantified using the OptiQuant Image analysis software and the digital light units in blot A (GE) were normalized to that in blot B (17-β E2).

Sequence Analysis of GE-specific Differential Products

To better understand the putative function of the GE-responsive genes present in the DP2 library, and to assess their involvement in estrogen receptor intercellular pathways, several clones that showed a GE-specific level of expression greater than 2-fold were sequenced and the resulting DNA sequence subjected to bioinformatics analysis (Altschul et al., 1997). We obtained information on the cDNA sequence, peptide sequence, genomic structure and gene expression pattern of 25 clones isolated by dual-subtractive hybridization and ddRT-PCR (Table 2, (Ramanathan and Gray, 2003)using the program BLAST and the Genbank/EMBL online bioinformatics database (Altschul et al., 1997). Several genes that perform a variety of biological functions, ranging from nucleic acid metabolism to signal transduction, are present in our library. As depicted in Table 2, sequence analysis showed 11 genes that are significantly regulated by phytoestrogen. Our screen identified two apoptosis genes, Caspase 2 isoform 3 and autophagy 12-like (APG12), the latter having been involved in apoptosis processes in cells deprived of nutrients (Ahn et al., 2007). Previous reports have shown that autophagy 12-like (APG12) is regulated by anti-estrogen in MCF-7 cells (Ahn et al., 2007; Ci-hui YAN et al., 2007). Our bioinformatics data revealed that two of our clones were involved in secondary messenger pathways. Clones PE.23 and PE.24 showed sequence homology to TAO kinase, and Guanine Nucleotide Binding protein, beta-1 subunit (GNB1), respectively. TAO kinase 3, which belongs to the MAPKKK family of kinases was induced 2.3-fold with the phytoestrogen GE. GNB1, which belongs to the family of heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory proteins (G-proteins), and mediates biological signaling across mammalian cell membranes, was induced 3.5-fold by GE. Collectively, these data indicated that we constructed a GE-specific differentially expressed library that contains putative-phytoestrogen responsive genes which may be used to study phytoestrogen function in breast cells.

TABLE II.

Putative phytoestrogen regulated genes identified by subtractive hybridization

| Clone | a cDNA (kbp) | b Fold Expression | Gene Name | Function of the Gene | Gene Bank Access number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE.14 | 0.8 | 2.0 | Peptidyl glycine alpha – amidating monooxygenase | C-terminal alpha amidation of peptides | NT_034772.5 |

| PE.15 | 1.0 | 2.5 | Autophagy 12-like (APG12) | Apoptosis, autophagy, Ubiquitin cycle | NW_922751.1 |

| PE.16 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 2-deoxyribose-5-phosphate aldolase homolog | Deoxyribonucleotide catabolism | NT_009714.16 |

| PE.17 | 0.7 | 2.5 | Zinc finger protein (C2H2 type) 277 | Regulation of Transcription, DNA dependent | NT_007933.14 |

| PE.18 | 0.7 | 2.0 | Spermidine/Spermine N1- acetyl transferase | Transferase Activity | NT_011575.15 |

| PE.19 | 0.75 | 3.0 | Zinc finger protein 404 | Regulation of Transcription, DNA dependent | NT_011109.15 |

| PE.20 | 0.7 | 2.4 | Rhomboid domain containing 1/Hypothetical protein DKFZp547E052 | Unknown | NT_005403.16 |

| PE.21 | 0.6 | 2.5 | Caspase 2 isoform 3 | Regulation of Apoptosis | NT_007914.14 |

| PE.22 | 0.6 | 2.5 | Nucleolar RNA associated protein beta isoform | Unknown | NW_924062.1 |

| PE.23 | 0.5 | 3.5 | Guanine Nucleotide Binding protein, beta-1 subunit | G-protein coupled receptor signaling pathway | NT_004350.18 |

| PE.24 | 0.7 | 2.3 | TAO Kinase 3 | MAPKKK cascade | NT_009775.16 |

Several DP2 clones that showed high levels of expression were sequenced and subjected to GeneBank/EMBL database analysis using the BLAST program. Gene identity was based on 100% match to the gene entry in the database. Gene function was determined from the GeneCard Data base.

Size of DP2 clone sequence subject to blast analysis.

Fold expression of GE responsive genes relative to E2, based on Northern blotting.

Guanine Nucleotide Binding protein, beta-1 subunit (GNB1) gene is phytoestrogen responsive

Over the past ten years it has became apparent that 17-β estradiol control of gene expression involves both genomic (classic) and non-genomic pathways (Bjornstrom and Sjoberg, 2005; Farhat et al., 1996b). Our SSH analysis and gene expression profiling of the differential product coupled with the bioinformatics analysis (Figs. 1 and 2 and Table 2) suggest that phytoestrogen may exert a non-genomic effect on gene expression by regulating the amount of the GNB1, a key player in the membrane mediated signal transduction cascade. To confirm that GNB1 was truly regulated by GE, we evaluated the level of GNB1 mRNA and protein expression in MCF-7 cells and in our DP2 subtracted hybridization library (Fig. 3). As shown in Figure 3, 100 nM GE elicited a significant increase in the levels of GNB1 mRNA and protein as measured by QRT-PCR, Northern and Western blot analysis. There was greater than a 2-fold increase in GNB1 mRNA expression with an accompanying 8-fold increase in protein expression in MCF-7 cells treated with GE for 24 h (Fig. 3A and 3C). We observed a marginal decrease in GNB1 mRNA levels during the same time period at high concentration of GE (Fig. 3A, insert). We corroborated the expression data by confirming the up regulation of GNB1 gene in the DP-2 library using real-time SYBR PCR. Figure 3B illustrated the abundant level of several genes in the library using 10 ng of the DP2 library DNA and gene specific primers for GNB1, pS2, PgR and GAPDH genes. Amplification of GNB1 cDNA was detected as early as cycle 15, whereas, amplification of GAPDH and pS2 genes occurred later at cycle 28 and 30, respectively, suggesting that the GNB1 gene is one of the most abundant in the subtracted library.

Figure III. Differential regulation of GNB1 gene by Genistein in MCF-7 cells.

(A) Relative quantification of GNB1 mRNA expression. Total RNA samples from GE treated MCF-7 cells were analyzed using SYBR Green Real Time RT-PCR. Relative quantification of GNB1 mRNA (Insert) was performed against the endogenous GAPDH gene and normalized with the no treatment control RNA. NT, no treatment control sample, NTC, no template control for PCR (B) Quantification of GNB1 in DP2 library. Plasmid DNA (1 ng) isolated from the DP2 library was amplified by SYBR Green Real Time PCR using gene specific primers for GNB1, pS2, PgR, and GAPDH. (C) GNB1 protein expression in MCF-7. MCF-7 cells were grown in 100 nM GE plus or minus ICI for 24 h, and 50 μg of total protein was analyzed by Western blot using anti-GNB1 primary antibody. The blot was probed with anti-GAPDH which was used as a loading control. (D). Northern blot analysis of GE induced GNB1 expression. Total RNA (30 μg) from GE treated MCF-7 was isolated and used in Northern blot analysis with 32P-labeled GNB1 cDNA as probe. The 18s rRNA was used as a loading control for Northern blot analysis.

Next, we determined whether the effect of GE on the GNB1 gene expression was dependent or independent of the ER. RNA from MCF-7 cells treated with GE and several phytoestrogens in the absence and presence of the anti-estrogen ICI-182,780 were analyzed by Northern blot using GNB1 cDNA insert as a probe and the levels of expression quantified relative to GADPH (Fig. 3C and Fig. 4). A single 3 kb transcript was detected for the GNB1 transcript in MCF-7 cells exposed to different PEs for 24 h (Fig. 3D). We observed significant stimulation of GNB1 mRNA levels, with GE being the most potent of the phytoestrogens tested (Fig. 4). At 100 nM, GE stimulated GNB1 expression 4- to 4.5-fold as compared to the control. In the presence of the antiestrogen ICI-182,780, GE induced expression of GNB1 was inhibited 50% suggesting that its expression is mediated through the ER (Fig. 4). There was a slight stimulation in GNB1 mRNA in the presence of 17-β estradiol which was not affected by ICI. Incubation of MCF-7 cells with other phytoestrogens such as Coumestrol and Zearalenone resulted in stimulation (4.5-fold, CO and 3.5-fold, ZE) of GNB1 expression in an estrogen receptor dependent manner (Fig. 4). Furthermore, real time PCR analysis of GNB1 expression in the presence of increasing concentration of these phytoestrogens indicates that there was significant increase in GNB1 expression levels (Data not shown)

Figure IV. Up regulation of GNB1 mRNA by phytoestrogen.

Total RNA (30 μg) was isolated from MCF-7 cells treated with 17-β E2 (10 nM) or PE (100 nM) ± 1 μM ICI antiestrogen for 24 h. Samples were separated by formaldehyde-agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred to a nylon membrane, UV cross-linked, and hybridized with 32P-labeled GNB1 cDNA probe generated by restriction enzyme digestion. The hybridized signals were scanned on a Packard Cyclone PhosphoImager and quantified using the OptiQuant Imager analysis software. Relative quantification of GNB1 mRNA expression was performed against the loading control 18s rRNA and normalized with the no treatment control. NT, no treatment control; ICI, antiestrogen ICI 182,780; 17-β Estradiol; GE, Genistein; CO, Coumestrol; and ZE, Zearalenone.

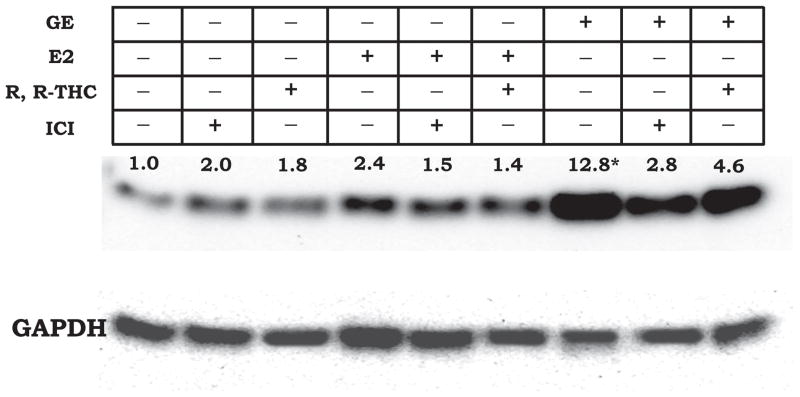

Regulation of GNB1 gene expression by phytoestrogens is mediated through both estrogen receptor subtypes

The regulatory function of estrogenic compounds such as GE may be mediated by at least two types of receptors, ERα and ERβ, present in mammalian systems. ERβ receptors have been shown to have a higher affinity for phytoestrogen as compared to ERα. In addition, the GNB1 signal transduction system has been implicated in mediating the membrane effects of 17-β estradiol and phytoestrogens (de Wilde et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2003; Stoica et al., 2003). Therefore, we investigated the effect of GE on the cellular protein levels of the GNB1 gene in MCF-7 cells in the presence of antagonists to either ERα or ERβ protein. Total protein isolated from MCF-7 cells treated with 100 nM GE in the presence and absence of the ERα antagonist ICI or ERβ specific antagonist cis-R,R-Diethyl-tetrahydrochrysene-2,8-diol (R, R-THC) (Gingerich and Krukoff, 2006; Rickard et al., 2002) were analyzed by western blot using a GNB1 specific antibody (Fig. 5). The GNB1 antibody detected an immuno-specific protein band at 35 kDa comparable to the predicted size of GNB1 (Fig. 5). In the presence of GE (100 nM for 24 h), GNB1 protein levels were increased 8- to 15-fold relative to the control. Co-incubation of MCF-7 with GE and ICI or GE and R, R-THC resulted in a significant decrease in GE-induced GNB1 protein levels. We observed that the GE-induced GNB1 protein level in the presence of the ERα antagonist, ICI-182,780, was decreased by 32%. In the presence of the ERβ antagonist R, R-THC, a 52% decrease in the GE-induced GNB1 protein level was observed. There was a marginal increase (0.8- to 1.0-fold) in GNB1 protein levels in the presence of 17-β E2. However, this increase was unaffected by the presence of either ICI or R, R-THC, suggesting that 17-β E2 does not regulate GNB1 protein levels. A decrease in the GE-induced mRNA and protein levels of GNB1 by anti-estrogens suggests that GE regulation of this gene is mediated through an ER pathway.

Figure V. Phytoestrogen regulatation of GNB1 protein expression through both ERα and ERβ.

MCF-7 cells were induced with GE in the presence and absence of ERα{antagonist (ICI) and ERβ antagonist (R,R-THC). Cellular GNB1 levels were determined by western blot analysis using anti-GNB1 antibody. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using enhanced chemilluminescence and the resulting signal was quantified with the AlphaEaseFC software. Protein expression of GAPDH was used as an internal control. Fold expression of GNB1 was normalized to the no-treatment control sample.

GNB1 gene promoter contains putative binding sites for estrogen receptor proteins

Next we substantiated the observation that GE regulates GNB1 expression in an estrogen receptor dependent manner by analyzing 1.0 kbp segments of the GNB1 promoter for putative transcription factor binding sites using several bioinformatics programs. The GNB1 gene is 106 kbp long and split into 12 exons. The transcription start site is located 332 bp upstream of the initiation codon. The MatInspector V2.2 program was used to analyze the sequence of a 1 kbp fragment (Accession Number NT_004350.18) upstream of the first exon of the GNB1 proximal promoter region (Fig. 6A) (Kitanaka et al., 2002; Kitanaka et al., 2001). The analysis revealed several potential regulatory elements of known transcription factors including Sp1, ER, NF- B, AP2, TFII-I and cAMP-response element binding (CREB) protein. There was, however, no TATA sequence present. The promoter region of the GNB1 gene was shown to have at least 4 half sites which fulfill the criteria for ER regulation of this gene.

Figure VI. Phytoestrogen-induced association of ERα with the GNB1 promoter.

MCF-7 cells were induced with 100 nM phytoestrogens (genistein and coumestrol) in the presence and absence of 1 μM ICI for 24 h. The cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde and the cross-linked DNA-protein complex fragmented by sonication followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-ERα antibody. The immunoprecipitated chromatin was analyzed by PCR for GNB1 promoter DNA and by Western for ERα and ERβ proteins. (A) Schematic representation of GNB1 indicating an ERE/Sp 1 site and the region amplified by GNB1 promoter primers. (B) PCR of GNB1 promoter immunoprecipitated by ERα antibody (left) and Western blot of immunoprecipitated protein (right). (C) PCR amplification of DNA from IP input (left) and PCR amplification of IP using primer pairs that amplify a region of GNB1 that does not contain ERE/Sp 1 binding sites (right), establishing that phytoestrogen recruits ERα to the GNB1 gene. (D) PCR of GNB1 promoter immunoprecipitated by ERβ antibody (left) and Western blot of immunoprecipitated protein (right).

To confirm that the GNB1 promoter contains functional ER regulatory features, we employed a ChIP assay to examine the direct interaction of the GE-ER complex with the GNB1 promoter. A formaldehyde cross-linked chromatin complex from MCF-7 cells induced with 100 nM GE or CO in the presence or absence of 1 μM ICI was immunoprecipitated using an anti-ER antibody. Analysis of the precipitated DNA for PE-dependent association between the ER and the GNB1 gene promoter using primer that would specifically amplify the ERE/Sp1 site revealed the direct binding of ERα to the 5′-flanking region of the GNB1 promoter (Fig. 6). PCR analysis of the precipitated DNA with a primer set for the proximal ERE half sites located in the GNB1 promoter revealed that GE and 17-β E2 promoted a 2- to 3-fold increase in ERα dependent binding (Figs. 6A and 6B, left panel). Immunoprecipitated chromatin from GE-treated MCF-7 cells obtained with anti-ER antibody generated a distinct PCR product with the ERE/Sp1 primer set, whereas cells incubated with CO showed no detectable PCR product under the same experimental conditions (Fig. 6B). On the other hand, there was a significant association of the ER to the GNB1 promoter in the presence of CO/ICI. The GE- and 17-β E2-induced ERα occupancy of the GNB1 promoter was specific in that coincubation with anti-estrogen ICI resulted in a decrease in the amount of GNB1 promoter that was immunoprecipitated. The specificity of ERα occupancy of the GNB1 promoter was confirmed by the inability to PCR-amplify a region of the GNB1 promoter that lacked any ERE or Sp1 sites (Fig. 6C). The chromatin input levels were confirmed when PCR was performed on non-immunoprecipitated DNA using ERE-Sp1 promoter and non-promoter primers. The specificity of the ChIP assay analysis was further confirmed by the failure to PCR amplify the proximal ERE half sites located in the GNB1 gene using chromatin precipitated with non-immune IgG. (Fig. 6D). As shown in Fig. 6B, right panel, there was an accompanying increase in the amount of ERα protein that was associated with the GNB1 promoter. In the presence of GE/ICI, there was a parallel decrease in the amount of receptor detected and the amount of promoter DNA amplified by PCR. We observed that there was no change in the amount of ERα protein precipitated in the absence and presence of ICI (Fig. 6B). This suggests that although all three compounds tested promote ERα promoter occupancy, only GE induces a receptor specific binding. Taken together, our results suggest that phytoestrogens are directly involved in regulating the gene expression of GNB1 at the chromatin level.

DISCUSSION

Phytoestrogens (PE) are polyphenolic compounds with unique chemical properties and biological activity relevant to estrogen-based diseases. PEs are suspected of eliciting chemo-preventative effects against breast cancer by influencing a wide range of biological activities, such as anti-estrogenic activity, anti-angiogenic activity, regulation of apoptosis, regulation of cell cycle progression, and tyrosine kinase inhibitory activity. The objective of this study was to identify and characterize genes that are activated or repressed by these compounds in an estrogen receptor dependent manner. Herein we have demonstrated that phytoestrogens regulate the expression level of several key signaling molecules that affect both nuclear and membrane receptor mediated gene transcription. Notably, we demonstrated that the expression level of the beta subunit of a membrane signal transducer (G-protein) molecule was regulated by genistein in MCF-7 cells in an estrogen receptor dependent manner.

The mechanism of PE activation of ER-mediated transcription of target genes has been studied extensively and the data obtained have revealed that both genomic and nongenomic signaling cascades are involved. The prototypical ER-regulated gene, pS2, a MCF-7 specific gene, is transcriptionally activated by a PE-ERα and PE-ERβ complex bound to the ERE site in the promoter of this gene. In endothelial cells, PEs activate endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) through protein kinase-mediated phosphorylation (Sobey et al., 2004; Tang et al., 2005; Woodman et al., 2004). PEs interact with ERs at the plasma membrane and associate with a variety of proximal signaling molecules such as G proteins (de Wilde et al., 2006; Fraser et al., 2006), Src kinase (Roberts, 2001), Ras kinase (Lei et al., 1998), and PI 3-kinase (Park et al., 2006). Activation of the ERα protein by PE leads to direct interaction of the PE protein complex with the type 1 Insulin-like growth factor (IGF-I) receptor present in the cell membrane, leading to activation of the IGF-I receptor, and hence activation of the MAPK signaling pathway (Kim et al., 2005). This nongenomic signaling by PE is coupled to the G-protein mediated signaling cascades and controls numerous essential functions in cells. The G-proteins are composed of a 36 – 52 kDa α-subunit, a 35 – 36 kDa β-subunit (GNB1) and an 8 – 10 kDa γ-subunit. In cells, the β- and γ-subunits are assembled into βγ dimers that act as functional units. Activation of membrane receptors by various stimuli such as PEs catalyzes the dissociation of the Gα and βγ subunits (de Wilde et al., 2006). Our study, for the first time, established that PEs regulate GNB1 subunit expression at the mRNA and protein levels in an ER-dependent manner. The ratio of βγ-subunit to α-subunit is critical in mediating the effect of certain signal transduction receptors and effectors at the cell membrane. Our data suggest that PEs may be initiating genomic and nongenomic transcriptional activity in cells by controlling the βγ/α – subunit ratio. The change in the βγ/α – subunit ratio could potentially change the execution of membrane-initiated stimuli in cells.

Using suppressive subtraction hybridization, QRT-PCR, and Northern and Western blot analysis, we showed that in MCF-7 cells the level of the β-subunit is up regulated by the PEs GE and CO. This suggests that PE has the ability to modulate the formation of an active G-protein by altering the amount of βγ-subunits in cells and subsequently the activation or repression of the membrane-mediated transcription cascade. This notion is supported by the observation that βγ functional monomer subunits play a direct signaling role in modulating the activity of some potassium channels and adenylyl cyclases, and interact with a number of signaling proteins (Clapham and Neer, 1997), including well known effectors such as phosphoinositide 3-kinases and phospholipases C, and more recently discovered interacting partners such as the ubiquitin-related protein PLIC-1(N’Diaye and Brown, 2003) and the glucocorticoid receptor (Kino et al., 2005).

The precise mechanism of phytoestrogen-mediated ER activation of GNB1 is unknown. We have examined the possibility of direct transcriptional regulation of GNB1 using the ChIP assay and through bioinformatics analysis of the GNB1 promoter. The promoter of the human GNB1 gene shows three Sp1 consensus sequences in close proximity to the transcriptional start site. Thus, the direct regulation of the GNB1 gene may occur through the binding of the ERα or ERβ to either the ERE half sites or Sp1 and AP-1 regulatory regions present in the promoter region of the GNB1 gene (Kitanaka et al., 2002). ChIP analysis demonstrated that phytoestrogen promotes the association of both subtypes of ER to the GNB1 promoter through binding to the ERα/Sp1 binding site present in the gene. Whether the phytoestrogen-mediated promoter occupancy of GNB1 by ER leads to gene activation is currently being investigated. However, our data suggest that there is an additional level of complexity in the non-genomic mechanisms of action of PEs in breast cancer cells. In summary, the effects of phytoestrogens on gene regulation involve increasing the levels of protein factors required for both membrane and nuclear signaling. As such, phytoestrogens profoundly influence cell function by regulating the regulators of signal transduction cascades.

References

- Adlercreutz H, Bannwart C, Wahala K, Makela T, Brunow G, Hase T, Arosemena PJ, Kellis JT, Jr, Vickery LE. Inhibition of human aromatase by mammalian lignans and isoflavonoid phytoestrogens. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;44(2):147–153. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(93)90022-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn CH, Jeong EG, Lee JW, Kim MS, Kim SH, Kim SS, Yoo NJ, Lee SH. Expression of beclin-1, an autophagy-related protein, in gastric and colorectal cancers. Apmis. 2007;115(12):1344–1349. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allred CD, Ju YH, Allred KF, Chang J, Helferich WG. Dietary genistin stimulates growth of estrogen-dependent breast cancer tumors similar to that observed with genistein. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22(10):1667–1673. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.10.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansonoff MA, Etgen AM. βββ elevates protein kinase C catalytic activity in the preoptic area of female rats. Endocrinology. 1998;139(7):3050–3056. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.7.6088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai Y, Uehara M, Sato Y, Kimira M, Eboshida A, Adlercreutz H, Watanabe S. Comparison of isoflavones among dietary intake, plasma concentration and urinary excretion for accurate estimation of phytoestrogen intake. J Epidemiol. 2000;10(2):127–135. doi: 10.2188/jea.10.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranda A, Pascual A. Nuclear hormone receptors and gene expression. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(3):1269–1304. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardies CM, Dees C. Xenoestrogens significantly enhance risk for breast cancer during growth and adolescence. Med Hypotheses. 1998;50(6):457–464. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(98)90262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S, Peterson TG. Biochemical targets of the isoflavone genistein in tumor cell lines. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1995;208(1):103–108. doi: 10.3181/00379727-208-43840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S, Peterson TG, Coward L. Rationale for the use of genistein-containing soy matrices in chemoprevention trials for breast and prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1995;22:181–187. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240590823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman JM, Allan GF, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O’Malley BW. Transcriptional activation by the estrogen receptor requires a conformational change in the ligand binding domain. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7(10):1266–1274. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.10.8264659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benten WP, Stephan C, Lieberherr M, Wunderlich F. Estradiol signaling via sequestrable surface receptors. Endocrinology. 2001;142(4):1669–1677. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.4.8094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biosystem A. ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System. 2001a. [Google Scholar]

- Biosystem A. User Bulletin #2: ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System. 2001b. [Google Scholar]

- Bjornstrom L, Sjoberg M. Mechanisms of estrogen receptor signaling: convergence of genomic and nongenomic actions on target genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(4):833–842. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawley OW, Barnes S. The epidemiology of prostate cancer in the United States. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2001;17(2):72–77. doi: 10.1053/sonu.2001.23056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson DM, Azios NG, Fuqua BK, Dharmawardhane SF, Mabry TJ. Flavonoid effects relevant to cancer. J Nutr. 2002;132(11 Suppl):3482S–3489S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.11.3482S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavailles V, Dauvois S, Danielian PS, Parker MG. Interaction of proteins with transcriptionally active estrogen receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(21):10009–10013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162(1):156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ci-hui YAN, Ya-ping YANG, Zheng-hong QIN, Zhen-lun GU, Paul REID, Z-qL Autophagy is involved in cytotoxic effects of crotoxin in human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 cells. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2007;28(4):540. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE, Neer EJ. G protein beta gamma subunits. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:167–203. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgan J, Wampler S, Manley JL. Interaction between a transcriptional activator and transcription factor IIB in vivo. Nature. 1993;362(6420):549–553. doi: 10.1038/362549a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wilde A, Heberden C, Chaumaz G, Bordat C, Lieberherr M. Signaling networks from Gbeta1 subunit to transcription factors and actin remodeling via a membrane-located ERbeta-related protein in the rapid action of daidzein in osteoblasts. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209(3):786–801. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dees C, Foster JS, Ahamed S, Wimalasena J. Dietary estrogens stimulate human breast cells to enter the cell cycle. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105(Suppl 3):633–636. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105s3633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolan CM, Harvey BJ. A Galphas protein-coupled membrane receptor, distinct from the classical oestrogen receptor, transduces rapid effects of oestradiol on [Ca2+]i in female rat distal colon. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;199(1–2):87–103. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhat MY, Abi-Younes S, Dingaan B, Vargas R, Ramwell PW. Estradiol increases cyclic adenosine monophosphate in rat pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells by a nongenomic mechanism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996a;276(2):652–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhat MY, Abi-Younes S, Ramwell PW. Non-genomic effects of estrogen and the vessel wall. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996b;51(5):571–576. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(95)02159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) transactivation by estrogen via the G-protein-coupled receptor, GPR30: a novel signaling pathway with potential significance for breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;80(2):231–238. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser LR, Beyret E, Milligan SR, Adeoya-Osiguwa SA. Effects of estrogenic xenobiotics on human and mouse spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(5):1184–1193. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Palacios V, Robinson LJ, Borysenko CW, Lehmann T, Kalla SE, Blair HC. Negative regulation of RANKL-induced osteoclastic differentiation in RAW264.7 Cells by estrogen and phytoestrogens. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(14):13720–13727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410995200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingerich S, Krukoff TL. Estrogen in the paraventricular nucleus attenuates L-glutamate-induced increases in mean arterial pressure through estrogen receptor beta and NO. Hypertension. 2006;48(6):1130–1136. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000248754.67128.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski J, Furlow JD, Murdoch FE, Fritsch M, Kaneko K, Ying C, Malayer JR. Perturbations in the model of estrogen receptor regulation of gene expression. Biol Reprod. 1993;48(1):8–14. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod48.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedelin M, Balter KA, Chang ET, Bellocco R, Klint A, Johansson JE, Wiklund F, Thellenberg-Karlsson C, Adami HO, Gronberg H. Dietary intake of phytoestrogens, estrogen receptor-beta polymorphisms and the risk of prostate cancer. Prostate. 2006a;66(14):1512–1520. doi: 10.1002/pros.20487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedelin M, Klint A, Chang ET, Bellocco R, Johansson JE, Andersson SO, Heinonen SM, Adlercreutz H, Adami HO, Gronberg H, Balter KA. Dietary phytoestrogen, serum enterolactone and risk of prostate cancer: the cancer prostate Sweden study (Sweden) Cancer Causes Control. 2006b;17(2):169–180. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy BA, Harvey BJ, Healy V. 17beta-Estradiol rapidly stimulates c-fos expression via the MAPK pathway in T84 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005;229(1–2):39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz MC. Cytokines and estrogen in bone: anti-osteoporotic effects. Science. 1993;260(5108):626–627. doi: 10.1126/science.8480174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh CY, Santell RC, Haslam SZ, Helferich WG. Estrogenic effects of genistein on the growth of estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 1998;58(17):3833–3838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JT, Jean TC, Chan MA, Ying C. Differential display screening for specific gene expression induced by dietary nonsteroidal estrogen. Mol Reprod Dev. 1999;52(2):141–148. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199902)52:2<141::AID-MRD4>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyder SM, Chiappetta C, Stancel GM. Interaction of human estrogen receptors alpha and beta with the same naturally occurring estrogen response elements. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57(6):597–601. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EJ, Shin HK, Park JH. Genistein inhibits insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling in HT-29 human colon cancer cells: a possible mechanism of the growth inhibitory effect of Genistein. J Med Food. 2005;8(4):431–438. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2005.8.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MH, Gutierrez AM, Goldfarb RH. Different mechanisms of soy isoflavones in cell cycle regulation and inhibition of invasion. Anticancer Res. 2002;22(6C):3811–3817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kino T, Tiulpakov A, Ichijo T, Chheng L, Kozasa T, Chrousos GP. G protein beta interacts with the glucocorticoid receptor and suppresses its transcriptional activity in the nucleus. J Cell Biol. 2005;169(6):885–896. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitanaka J, Kitanaka N, Takemura M, Wang XB, Hembree CM, Goodman NL, Uhl GR. Isolation and sequencing of a putative promoter region of the murine G protein beta 1 subunit (GNB1) gene. DNA Seq. 2002;13(1):39–45. doi: 10.1080/10425170290019883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitanaka J, Wang XB, Kitanaka N, Hembree CM, Uhl GR. Genomic organization of the murine G protein beta subunit genes and related processed pseudogenes. DNA Seq. 2001;12(5–6):345–354. doi: 10.3109/10425170109084458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight DC, Eden JA. A review of the clinical effects of phytoestrogens. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(5 Pt 2):897–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori A, Yatsunami J, Okabe S, Abe S, Hara K, Suganuma M, Kim SJ, Fujiki H. Anticarcinogenic activity of green tea polyphenols. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1993;23(3):186–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamon-Fava S, Micherone D. Regulation of apoA-I gene expression: mechanism of action of estrogen and genistein. J Lipid Res. 2004;45(1):106–112. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300179-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Mellay V, Grosse B, Lieberherr M. Phospholipase C beta and membrane action of calcitriol and estradiol. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(18):11902–11907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.11902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Mellay V, Lasmoles F, Lieberherr M. Galpha(q/11) and gbetagamma proteins and membrane signaling of calcitriol and estradiol. J Cell Biochem. 1999;75(1):138–146. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19991001)75:1<138::aid-jcb14>3.3.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Jin Y, Lim W, Ji S, Choi S, Jang S, Lee S. A ginsenoside-Rh1, a component of ginseng saponin, activates estrogen receptor in human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;84(4):463–468. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei S, Dryden WF, Smith PA. Involvement of Ras/MAP kinase in the regulation of Ca2+ channels in adult bullfrog sympathetic neurons by nerve growth factor. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80(3):1352–1361. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.3.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberherr M, Grosse B, Kachkache M, Balsan S. Cell signaling and estrogens in female rat osteoblasts: a possible involvement of unconventional nonnuclear receptors. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8(11):1365–1376. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650081111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews J, Wihlen B, Tujague M, Wan J, Strom A, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptor (ER) beta modulates ERalpha-mediated transcriptional activation by altering the recruitment of c-Fos and c-Jun to estrogen-responsive promoters. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(3):534–543. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei J, Yeung SS, Kung AW. High dietary phytoestrogen intake is associated with higher bone mineral density in postmenopausal but not premenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(11):5217–5221. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.11.8040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina MJ, Persky V, Setchell KD, Barnes S. Soy intake and cancer risk: a review of the in vitro and in vivo data. Nutr Cancer. 1994;21(2):113–131. doi: 10.1080/01635589409514310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio A, Di Domenico M, Castoria G, de Falco A, Bontempo P, Nola E, Auricchio F. Tyrosine kinase/p21ras/MAP-kinase pathway activation by estradiol-receptor complex in MCF-7 cells. Embo J. 1996;15(6):1292–1300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musey PI, Adlercreutz H, Gould KG, Collins DC, Fotsis T, Bannwart C, Makela T, Wahala K, Brunow G, Hase T. Effect of diet on lignans and isoflavonoid phytoestrogens in chimpanzees. Life Sci. 1995;57(7):655–664. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00317-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- N’Diaye EN, Brown EJ. The ubiquitin-related protein PLIC-1 regulates heterotrimeric G protein function through association with Gbetagamma. J Cell Biol. 2003;163(5):1157–1165. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nethrapalli IS, Tinnikov AA, Krishnan V, Lei CD, Toran-Allerand CD. Estrogen activates mitogen-activated protein kinase in native, nontransfected CHO-K1, COS-7, and RAT2 fibroblast cell lines. Endocrinology. 2005;146(1):56–63. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Chung SW, Kim SH, Kim TS. Up-regulation of interleukin-4 production via NF-AT/AP-1 activation in T cells by biochanin A, a phytoestrogen and its metabolites. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;212(3):188–199. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan L, Gray WG. Identification and characterization of a phytoestrogen-specific gene from the MCF-7 human breast cancer cell. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2003;191(2):107–117. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(03)00221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razandi M, Pedram A, Merchenthaler I, Greene GL, Levin ER. Plasma membrane estrogen receptors exist and functions as dimers. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18(12):2854–2865. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickard DJ, Waters KM, Ruesink TJ, Khosla S, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Riggs BL, Spelsberg TC. Estrogen receptor isoform-specific induction of progesterone receptors in human osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17(4):580–592. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.4.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE. Role of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk) signal transduction cascade in alpha(2) adrenoceptor-mediated vasoconstriction in porcine palmar lateral vein. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133(6):859–866. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robyr D, Wolffe AP, Wahli W. Nuclear hormone receptor coregulators in action: diversity for shared tasks. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14(3):329–347. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.3.0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodan GA, Martin TJ. Therapeutic approaches to bone diseases. Science. 2000;289(5484):1508–1514. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santell RC, Chang YC, Nair MG, Helferich WG. Dietary genistein exerts estrogenic effects upon the uterus, mammary gland and the hypothalamic/pituitary axis in rats. J Nutr. 1997;127(2):263–269. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Hu X, DiRenzo J, Lazar MA, Brown M. Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell. 2000;103(6):843–852. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobey CG, Weiler JM, Boujaoude M, Woodman OL. Effect of short-term phytoestrogen treatment in male rats on nitric oxide-mediated responses of carotid and cerebral arteries: comparison with 17beta-estradiol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310(1):135–140. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.063255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song RX, Fan P, Yue W, Chen Y, Santen RJ. Role of receptor complexes in the extranuclear actions of estrogen receptor {alpha} in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13(Suppl 1):S3–S13. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoica GE, Franke TF, Wellstein A, Czubayko F, List HJ, Reiter R, Morgan E, Martin MB, Stoica A. Estradiol rapidly activates Akt via the ErbB2 signaling pathway. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17(5):818–830. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvia VL, Walton J, Lopez D, Dean DD, Boyan BD, Schwartz Z. 17 beta-estradiol-BSA conjugates and 17 beta-estradiol regulate growth plate chondrocytes by common membrane associated mechanisms involving PKC dependent and independent signal transduction. J Cell Biochem. 2001;81(3):413–429. doi: 10.1002/1097-4644(20010601)81:3<413::aid-jcb1055>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang BY, Adams NR. Effect of equol on oestrogen receptors and on synthesis of DNA and protein in the immature rat uterus. J Endocrinol. 1980;85(2):291–297. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0850291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YB, Wang QL, Zhu BY, Huang HL, Liao DF. Phytoestrogen genistein supplementation increases eNOS and decreases caveolin-1 expression in ovariectomized rat hearts. Sheng Li Xue Bao. 2005;57(3):373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toran-Allerand CD. Minireview: A plethora of estrogen receptors in the brain: where will it end? Endocrinology. 2004;145(3):1069–1074. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meeuwen JA, Ter Burg W, Piersma AH, van den Berg M, Sanderson JT. Mixture effects of estrogenic compounds on proliferation and pS2 expression of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45(11):2319–2330. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade CB, Dorsa DM. Estrogen activation of cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate response element-mediated transcription requires the extracellularly regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Endocrinology. 2003;144(3):832–838. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DY, Fulthorpe R, Liss SN, Edwards EA. Identification of estrogen-responsive genes by complementary deoxyribonucleic acid microarray and characterization of a novel early estrogen-induced gene: EEIG1. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18(2):402–411. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitten PL, Russell E, Naftolin F. Influence of phytoestrogen diets on estradiol action in the rat uterus. Steroids. 1994;59(7):443–449. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(94)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman OL, Missen MA, Boujaoude M. Daidzein and 17 beta-estradiol enhance nitric oxide synthase activity associated with an increase in calmodulin and a decrease in caveolin-1. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44(2):155–163. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200408000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Niwa K, Onogi K, Tang L, Mori H, Tamaya T. Effects of selective estrogen receptor modulators and genistein on the expression of ERalpha/beta and COX-1/2 in ovarectomized mouse uteri. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2007;28(2):89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]