General Overview

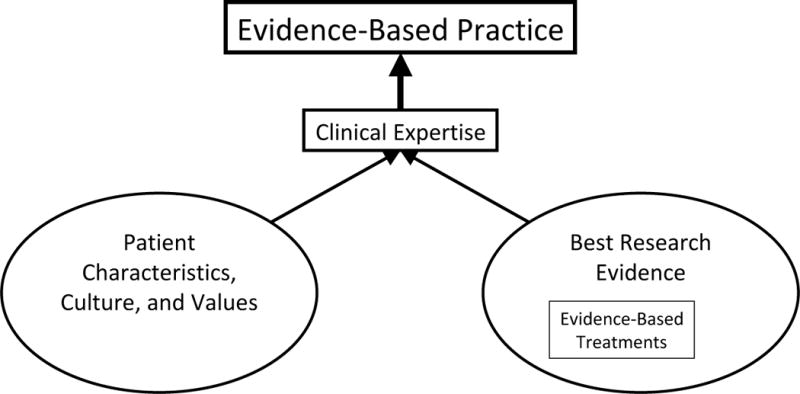

The increasing diversity of American society and the recognition of widening health disparities have resulted in the need to improve how we address issues of culture and context in mental health services and research[1, 2]. Ethnic minority children continue to have substantial unmet mental health needs and evidence-based treatments have proven challenging to disseminate widely among ethnic minority communities[3]. Indeed, policy makers have made an important distinction between evidence-based treatments – interventions that have proven efficacy in clinical trials – and evidence-based practice, which involves “the integration of the best available research with clinical expertise in the context of patient characteristics, culture, and preferences”[4], which is illustrated in Figure 1. However, despite the publication of multiple cultural competence guidelines, researchers, policy makers, and service providers continue to debate over the conceptualization and implementation of cultural competence – and key components of true “Evidence-Based Practice”[5]. Moreover, the number of treatments that have a solid evidence base for use with ethnic minorities continues to lag behind that for the majority population[6, 7]. This combination of very few evidence-based treatments for ethnic minorities and the continuing controversies around the operationalization of cultural competence in real-world settings has resulted in a paucity of robust models for the implementation of Evidence-Based Practices as envisioned by the Institute of Medicine and professional societies[4, 8].

Figure 1.

The relationship between evidence-based treatment and evidence-based practice.

From American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Treatment. Evidence-based treatment in psychology. Am Psych 61:271–85, 2006; with permission.

Although the value of diversity and the importance of recognizing the impact of culture and context on treatment and treatment outcomes have been well established, research on cultural adaptation of treatments for specific ethnic groups is equivocal. Some work suggests that tailoring interventions for specific populations can increase its effectiveness [9–12], while others argue that there is little support for ethnic-specific interventions[13]. In fact, some research also points to deleterious effects when core components of clinical treatments are diluted during the process of culturally adapting an intervention[14], suggesting that fidelity to evidence based treatments is important for improving outcomes for all communities. At the same time, culturally sensitive adaptations (e.g., use of cultural concepts, addressing issues of migration, family values, language, etc.) and implementation (e.g., client ethnic match, availability of materials in specific languages, working with cultural brokers, etc.) of services do relate to community and client engagement as well as retention in mental health treatment[15–17]. What appears to be important is to strike a balance between treatment fidelity to the original Evidence-Based Treatment and the incorporation of culturally-informed care, resulting in this notion of Evidence-Based Practice.

This chapter[E1] will describe the historical context of culture-specific adaptations of evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents and recent frameworks for determining when adaptations are needed. It will also address how to integrate culturally sensitive care while maintaining fidelity to an intervention and the broad public health perspective of engaging with ethnic minority communities and delivering these interventions in settings and in ways that are accessible and acceptable to diverse children and their families. We will then summarize the state of the literature of evidence-based treatments for several common child psychiatric disorders as it pertains to ethnic minority populations, and discuss recommendations for future research.

History/Background

In 2001, the Surgeon General’s Report on Mental Health—Race, Culture, and Ethnicity documented the paucity of studies demonstrating efficacious treatments for ethnic minorities of all ages[2]. Despite the growing awareness in the mental health field of disparities in care and the identification of key characteristics of cultural competence, few interventions had been designed to study efficacy in ethnic minority populations. To address this issue, some investigators have focused efforts on adapting evidence-based treatments for specific populations, although few have been rigorously studied. For example, one parenting program, adapted for Mexican American families[18], identifies specific beliefs and attitudes about the intervention prior to implementation and then incorporates and tailors the intervention to address beliefs that may be counter to participating in the intervention. However another adaptation for Cuban Americans participating in a family therapy intervention[19] did not demonstrate improvement over the standard intervention. Researchers are beginning to call into question whether or not adaptations are necessary for all interventions and proposing that if adaptations are made, they be “selective and directed”, based on empirical evidence that suggests that without adaptations to address specific issues, there would be a high likelihood that the intervention would be less effective for the target population[20].

Another approach to delivering interventions for ethnic minority youth has been in the actual implementation and tailoring of evidence based treatments, while maintaining fidelity to the core components of the effective intervention and thereby not making significant adaptations to the original treatment[21]. One example of this is a community-partnered approach in which multiple stakeholders from a given community collaborate with clinicians and researchers in all aspects of the delivery of a program, including during the pre-planning of an intervention, identifying ways to build on the strengths of a given community in the implementation of a program, and addressing key concerns and needs within the community that should be addressed in delivering services[22]. Finally, providing access to evidence based treatments that are delivered in a culturally sensitive manner in settings that are more acceptable and convenient for diverse youth and their families than hospitals and clinics (e.g., schools, churches), may ultimately be an important way in which disparities are minimized.

Previous research has described important cultural issues to integrate into any treatment for ethnic minority children and families such as help-seeking preferences, expressions of distress, communication styles, migration experiences, family values, and sociopolitical history[9]. These concepts are often central to understanding the experience of specific ethnic minority populations and are elaborated upon in other papers[E2] in this issue. Providing evidence based treatments that incorporate these important culturally relevant components to care, yet maintain fidelity to known effective treatments is an important balance in delivering services to some of our most vulnerable populations, and is at the heart of the concept of Evidence-Based Practice, but remains challenging to achieve.

Another challenge in implementing many Evidence-Based Treatments is whether the human services institutions serving a particular minority community has the necessary financial, infrastructural, and human resources necessary to implement a specific treatment[23]. For example, interventions that are designed for delivery by Masters-level professionals may be difficult to implement in service systems that are heavily reliant on bachelors-level providers and paraprofessionals[24]. Evidence-Based Treatments that are highly complex, require substantial training and supervision to implement and involve significant up-front costs to incorporate into a system are much less likely to be used by programs serving minority communities, as they often lack the additional resources necessary to incorporate new treatments into their programs and maintain them over time[8, 23]. Unfortunately, because many Evidence-Based Treatments were first developed and implemented in well-resourced, University-supported settings, they often have basic structural requirements that are beyond the reach of many programs serving minority communities.

Developmental Considerations

Similar to cultural considerations, the importance of developmental factors has historically been important in child and adolescent psychiatry. Many Evidence-Based Treatments were first developed for adult populations with very little regard for important sociocultural factors affecting children—such as local beliefs regarding appropriate child rearing practices and the cultural norms for child behavior that are essential in treating children and adolescents. For example, many American Indian cultures emphasize the development of autonomy and independence at very young ages and reinforce learning skills that rely on observation and experience rather than direct instruction[25]. In our review of Evidence-Based Treatments in the following section, we pay particular attention to characteristics of the populations studied in terms of both age and culture.

Major Empirical Findings

Although not meant to be an exhaustive description of the U.S. child & adolescent psychotherapy treatment literature, this next section highlights examples of Evidence-Based Treatments. These psychotherapy interventions have been rigorously studied in at least one randomized controlled trial, and also include a majority of ethnic minority youth in the sample or have specific treatment analyses of ethnic minorities. For this discussion, we focus on interventions targeting the following conditions: depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, conduct disorder, and substance use disorders. Given the limited scope of this discussion preventive interventions have been excluded in this summary, although we recognize that the prevention field has numerous examples of effective interventions that have included ethnic minority children and adolescents in evaluations. Illustrations will be presented of specific considerations for particular populations when applicable and ways in which the study captured the concept of Evidence-Based Practice.

Depressive Disorders

Treatment for child and adolescent depression has been widely studied with good evidence for the effectiveness of CBT [26, 27]. The AACAP Practice Parameters (2007) on assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders included various studies on psychosocial interventions and recommendations for treatment[28]. Few of the studies discussed were conducted with primarily ethnic minority populations. Likewise, in Weisz and colleague’s (2006) meta-analysis of thirty-five studies on psychotherapy for child and adolescent depression, few studies were conducted with samples where there was a majority of ethnic minority children[27]. Exceptions with positive effect sizes include two studies examining Interpersonal Therapy for Adolescents[29, 30], one study comparing IPT and CBT to waitlist-control[31], one quality improvement intervention including CBT, and one study examining Attachment-based family therapy[32].

Interpersonal Therapy for Adolescents (IPT-A) has been evaluated with a low-income, Latina female sample. It has been successfully implemented in urban school-based health clinics serving minority students and has been shown to significantly reduce depressive symptoms and improve social and general functioning [29]. Rosselló and Bernal (1999) evaluated IPT-A and CBT in comparison to a wait-list control among Puerto Rican adolescents[31]. Both IPT and CBT were more effective that the wait-list control group in reducing depressive symptoms. In addition, both interventions were adapted to include the “interpersonal” aspects of the Latino culture. For example, the cultural values of familism and respeto (“respect”) were incorporated into both IPT and CBT interventions. IPT had positive outcomes on self-concept and social adaptation over the wait-list control. No such changes were evident for CBT. The authors suggest IPT may be more compatible with Puerto Rican cultural values of personalismo (“personalism”; i.e., the preference for personal contacts in social situations) and familismo (“familism”; i.e., the tendency to place the interest of the family over the interests of the individual) shared by most Latino groups[33–35].

A follow up study in Puerto Rican adolescents compared individual and group formats of both IPT and CBT and found that both CBT arms were superior to IPT, and no differences were found between individual and group modality for either intervention [36]. Although both IPT and CBT can be effective in this population, CBT resulted in a greater reduction in depressive symptoms. The authors suggest that CBT may offer faster symptom relief than IPT, due to its structured, concrete, and directive approach, which may be consonant with the cultural value of respeto (e.g., looking up to authority figures for guidance).

The Youth Partners in Care (YPIC) quality improvement intervention also included a CBT component (in addition to medications), which was delivered in a primary care setting to a large sample of ethnic minority youth [37]. The YPIC training included a focus on cultural sensitivity and tailoring of examples to fit within the cultural context of each youth and family. For example, the concept of “simpatico” (warm and caring interactions and concern for the whole family) was integrated into the care of Latino clients. In examining the differential effects of the YPIC intervention in Latino, African American, and Caucasian youth, African Americans in YPIC were found to have significantly greater improvement in depressive symptoms than those in usual care, and YPIC Latino adolescents reported significantly greater treatment satisfaction than those in usual care. No intervention effects were found for Caucasian youth[38].

Though CBT and IPT have the greatest evidence base, Diamond et al. (2002) developed and evaluated Attachment-based Family therapy among a sample of 32 adolescents (78% female, 69% African American)[32]. The treatment showed a greater reduction in depression symptoms compared to a waitlist control group. The authors note that the majority of the sample was comprised of low-income, inner- city African American females who were family oriented and had experienced high rates of trauma and loss. Thus, the authors believed the goals of improving communication, repairing trust, and resource building were engaging, important, and relevant for this population.

Anxiety Disorders

Similar to the literature on depression interventions, studies have also supported the use of CBT as probably efficacious in treating anxiety symptoms in youth for separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, social phobias[39–41], and specific phobias[42], with benefits extending up to 5 years post-treatment [40]. However, few studies have examined CBT for childhood anxiety in ethnic minority youth. Silverman and colleagues (1999) found that a group CBT compared to a waitlist control improved anxiety symptoms, with no differences found in treatment effect between Caucasian and Latino youth [43]. Ginsberg and Drake (2002) adapted this group CBT for low-income African American adolescents[44]. These adaptations included shortening the number of sessions and length of sessions for easier delivery within the school setting, a setting specifically selected in order to improve access for these African American students. Treatment adaptations included modifications of specific examples used throughout treatment which allowed for more relevant situations to be discussed within the context of learning new coping skills. Finally, the parent component was excluded from this adaptation due to the parents’ work schedules and transportation barriers in attending sessions. In a small pilot study, this adapted group CBT intervention was found to be more effective than an attention-support control condition for African American adolescents.

Aside from CBT, anxiety management training, study skills training, and a combination of these two skills was found to improve test anxiety in African American youth compared to either an attention control condition or no treatment[45].

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Trauma specific therapies have been shown to be more effective in decreasing symptoms of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) than nonspecific therapies in preschoolers, school-age children, and adolescents[46]. In addition, there is growing evidence that these trauma treatments are effective in ethnic minority youth with PTSD symptoms, without major adaptations to the original interventions needed for effectiveness. The most well-studied intervention for traumatized children is Trauma Focused-Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT), a 12 session individual CBT that also involves parent-child dyadic sessions. In a multi-site randomized controlled trial for sexually abused children, Cohen and colleagues found that TF-CBT resulted in greater improvement in PTSD and other symptoms compared to those who received Child Centered Therapy (CCT). Although the majority of children studied were Caucasian, this study included 28% African American children, and no differences in effectiveness by ethnicity were found.

A 10-session group trauma intervention, the Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS), was originally developed within a community partnered framework to serve a multiethnic inner-city population, and was designed to be implemented within the school setting to enhance the access to trauma services for underserved ethnic minority youth[47]. In a randomized controlled study of 126 primarily Latino sixth grade students, CBITS significantly improved symptoms of both PTSD and depression in traumatized students receiving the intervention, compared to those in a waitlist control group[48]. This intervention has also been found to be effective in a study of Latino immigrant students, delivered in Spanish by bilingual, bicultural school-based clinicians[49].

Another approach to treating childhood trauma that has been found to be effective is a longer-term treatment (50 weeks) that alleviates trauma symptoms in preschool children by improving the child-mother relationship and the support for the child in coping with the trauma. Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP), an intervention based in attachment theory, has been studied in a sample of ethnically diverse preschoolers exposed to marital violence [50]. The strategies used in CPP are also influenced by an ecological theoretical framework that builds on the strengths of traditional cultural practices and takes into account the effects of discrimination, poverty, and social inequities. Results of this study indicate that children who received CPP compared to those randomized to case management had greater improvement in traumatic stress symptoms and overall behavior problems.

Conduct Disorder

There is now strong evidence for the effectiveness of several treatments, most of which take a multimodal, family-centered approach to addressing the problems associated with conduct disorder[51, 52]. This is also one area of child psychotherapy research in which a number of studies have been conducted with ethnic minority youth, especially African American and Latino youth.

Multisystemic therapy (MST) has been studied in several randomized controlled studies of multiethnic, mainly African American, populations with delinquency and conduct symptoms and has been found to be effective in reducing such outcomes as re-arrest rates, time incarcerated, and self-reported offenses[53–56]. Using a social-ecological framework, MST intervenes with multiple systems by individualizing the treatment with the family, peers, and school and takes into account the sociocultural context of each youth and family[56]. MST emphasizes the multidetermined nature of antisocial behavior and strives to deliver services to adolescents and their families in naturalistic settings. Studies of MST have demonstrated its positive impact on family correlates of antisocial behavior as well as adjustment in family members. Moreover, after a 4 year follow-up MST was shown to significantly reduce future criminal behavior[54].

The Coping Power intervention has also been shown to improve disruptive and delinquent behaviors in pre-adolescent aggressive Caucasian and African American boys [57, 58]. The Coping Power intervention includes a cognitive behavioral school-based group component for children that teaches such skills as use of self statements, distraction, relaxation, and social problem solving. A group parent training component is also included. These studies have been conducted assessing the overall effectiveness of the intervention and no moderation effect due to ethnicity has been found[58].

Substance Use Disorders

The AACAPs Practice Parameters for Substance Use Disorders identified cognitive behavioral therapy with or without motivational enhancement therapy [59, 60] as well as family therapy approaches [61, 62] as having the strongest evidence base for use with adolescents, but few of the studies have focused on the efficacy of substance abuse interventions for minority youth. In two randomized clinical trials that examined substance use problems, participants (53–69% from ethnic minority groups) who received Multisystemic Therapy (MST—described earlier in this paper[E3]) had reduced use of alcohol and marijuana in comparison to youths who received usual community services. Multidimensional Family Therapy (MDFT) focuses on developing better problem solving, coping, and interpersonal skills [62]. Three clinical trials of MDFT[60, 62–64] have included a 49–96% ethnic minority adolescent population in the sample, and have consistently demonstrated the superiority of MDFT for reducing substance use in comparison with other treatments including adolescent/peer group therapy, CBT, and a multifamily educational intervention. Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (ACRA) focuses on building communication and problem solving skills in both individual and family sessions with the goal of reducing substance use and related problems [65]. One of the clinical trials of ACRA focused on a sample of homeless adolescents (59% from ethnic minority groups) and found that adolescents who received this intervention had significantly reduced substance use compared to usual care[65].

Guidelines for Current Practice

As these examples from the literature suggest, the current evidence base is far from optimal in terms of guiding the selection, tailoring, and implementation of specific evidence-based treatments in minority communities. While we are acutely aware of these scientific limitations, multiple studies have now clearly documented that ethnic minority youth have greater unmet need for mental health services than the general population. Minority communities are in great need for access to interventions that are effective, feasible, and acceptable, while researchers continue to build this evidence base. From our brief summary of some of the EBTs that have been studied in ethnic minority populations, there appears to be growing empirical support that EBTs can be implemented effectively in ethnic minority communities. The following suggested guidelines support such efforts, while also being mindful of the significant limitations of the scientific literature.

-

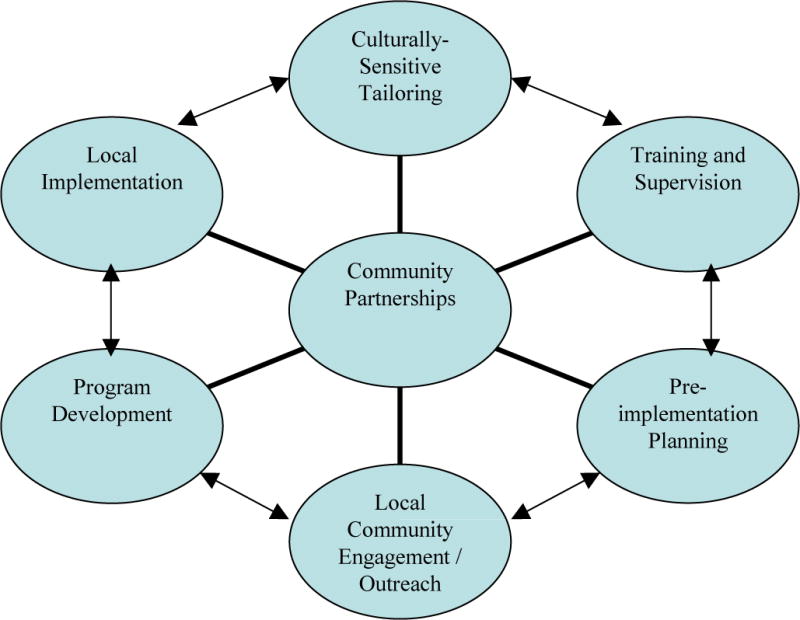

Partnerships First. Collaboration with community stakeholders who have cultural knowledge and clinical expertise is critical to selecting interventions that are consistent with community priorities and needs, and to implementing them in ways that are congruent with and respectful of a community’s cultural context. Local community partners can also help identify ways to increase access, engagement, and retention in treatment. Figure 2 illustrates the broad extent to which community partnerships can improve each stage of delivering EBTs:

Delivering EBTs in community settings and with local providers may also help address barriers to care, including those that accompany poverty. Ethnic minority children are disproportionately poor, with an estimated 35% of African American children, 31% of Latino children, 31% of American Indian children, and 15% of Asian children living in poverty, compared to 11% of White children [66]. Parents of poor and ethnic minority children often report cost, language, distance, transportation, time, belief that treatments may not help, and possible stigma as barriers to seeking services for their children. By partnering with communities and addressing identified needs, parents may feel more positive about the treatment helping them and their children, and may reduce stigma. In addition, partnerships within communities can work with parents to minimize barriers such as time, transportation, and distance, which may also increase acceptability of these treatments among community members.

Choosing what to implement. Specific EBTs should be assessed for their ability to address the specific priorities and needs that are identified through the above community collaborative process. This assessment of EBTs should also determine whether or not the intervention relies on techniques or materials that might violate local norms and beliefs or require human, infrastructural, and fiscal resources necessary to implement the EBT. From the summary of interventions presented in this chapter,[E4] there is evidence to suggest that EBTs are effective for ethnic minority populations, and in some cases, more effective than in the majority group[38]. Thus it is prudent for clinicians to choose EBTs over other less well-studied interventions, even if data is not available for the specific population to be treated, unless there is evidence that an EBT is ineffective in that population[20]. After choosing an EBT, there needs to be a balance between maintaining fidelity to the original treatment model while practicing the EBT in a culturally sensitive manner, what we refer to as Evidence-based Practice (Figure 1).

Considering systems issues when choosing and implementing EBTs. Delivering EBTs in community settings and non-mental health specialty sectors such as schools, primary care settings, and perhaps even community organizations such as churches can be especially important in ethnic minority communities. Our summary of the empirical literature also points to a number of EBTs that have been implemented in such settings with ethnic minority youth effectively. This point is exemplified in a recent study of ethnic minority youth who were in need of treatment for trauma-related mental health symptoms following Hurricane Katrina[67]. When youth were randomized to either receive EBT in a school or in a clinic setting, striking differences in uptake of these EBTs emerged. In the school-based setting, 98% of youth began treatment and 91% completed treatment. In contrast, 37% of youth assigned to receive treatment in the clinic came to their first appointment and only 15% completed treatment. It cannot be emphasized enough not only how important providing EBTs can be for improving the quality of care for ethnic minority youth, but also how vital it is to providing these services in places where youth can readily receive them.

Monitor the implementation of EBTs and remain open to further tailoring of these treatments as needed. It is impossible to fully anticipate the way a particular EBT will perform in a given clinical setting, even if it is selected carefully. Incorporating a continuous quality improvement framework that seeks to systematically assess how clients are responding to a particular EBT is particularly important if an EBT has not been well-studied in a community. Collaborating with indigenous community partners to identify the key outcomes to be monitored and to adjust the implementation strategy as necessary can be invaluable, especially in delivering EBTs to ethnic minority communities.

Figure 2.

Model for using community partnerships to provide culturally sensitive evidence-based treatment

From Ngo V, Langley AK, Kataoka SH, et al.: Providing evidence-based practice to ethnically diverse youths: examples from the Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) program. J Am Acad of Child and Adolesc Psychaitry 47:859, 2008; with permission.

Research Priorities

Finally, our summary of the current state of the science of EBTs for ethnic minority youth presents a compelling argument for the need for researchers to address a number of highly salient questions for the implementation of true evidence-based practice in minority communities.

How can community partnership and engagement in research facilitate the development and implementation of EBTs and practice? Just as service providers should partner with the community in selecting and implementing interventions, researchers should also develop such partnerships to guide their development and evaluation of the evidence base [68]. One method of balancing treatment fidelity and adhering to culturally-informed care is through a process of Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR), in which there is equal partnership between community members and researchers from the inception of the intervention, through all stages of development, implementation, and evaluation of a treatment program[22, 69]. Current efforts to study the effect of CBPR on disseminating EBT for adult depression is underway[70]; however, rigorous evaluations of a similar approach in child mental health is lacking. Studies that determine the effect of CBPR on EBT development and implementation and dissemination of EBPs could provide new innovations to further decrease the disparities in mental health services for ethnic minority youth populations.

-

How can dissemination and implementation be a priority as EBTs are designed and evaluated? It is critical that new interventions be designed at their outset to be culturally appropriate, acceptable, feasible, and sustainable. A CBPR process can be extremely helpful in this regard. The current evidence base largely consists of studies of efficacy conducted with carefully selected participants and highly-trained, closely-supervised clinicians. While efficacy studies can demonstrate that a given intervention works in optimal conditions, the programs serving minority communities are rarely able to deliver care in such an exacting way. Thus there is a substantial need for effectiveness research that is conducted in real-world clinical settings that serve minority communities, utilizes less stringent selection criteria, addresses barriers when possible, and supports clinicians in ways that are consistent with community practice. Frameworks such as RE-AIM contrasts efficacy and effectiveness research on several domains: Reach, Efficacy or Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance and Cost [71] can be a useful rubric for balancing our research efforts across all aspects of supporting evidence-based practice rather than focusing specifically on demonstrating efficacy.

One way to address the lack of available clinicians in low-income ethnic minority communities is to focus research efforts on developing treatments delivered by lay health workers and the existing non-clinical workforce in community settings in order to expand the access of EBTs. For example, research that explores the roles of non-mental health providers in either supporting the delivery of EBTs or actually implementing the intervention altogether are important next steps in increasing care to the broad number of children and families currently not receiving needed care. For example, similar to the role of teachers in school-based prevention efforts, studies of EBTs that target psychiatric symptoms in youth designed for teachers and other school staff to deliver are underway[72].

How can we increase our understanding of factors relevant to the effect of EBTs with ethnic minority youth and families? One continued recommendation that has been sounded by several others in the past, is the need to increase the inclusion of ethnic minority populations in treatment research studies[73]. There is a particular paucity of studies that include Asian and American Indian youth in psychosocial intervention research across psychiatric conditions. Immigrant populations, especially the growing immigrant Latino populations and other non-English speakers, have frequently been excluded from participation in research, and are significantly underrepresented in treatment studies despite having unique risks for poor access of mental health treatments. Not only is there a need for more funding agencies to support these efforts, but researchers need to develop new ways of creatively expanding participation of communities in research. Creating an infrastructure within underrepresented communities of color to better support community participatory research may be one strategy to expand the diversity of research samples that currently exist in research studies.

In conclusion, the dissemination of EBTs to ethnic minority children, adolescents, and families can be challenging. The current research evidence suggests that a number of interventions have been found to be effective in ethnic minority populations without need for major adaptations of the original interventions. However, in this paper[E5] we have highlighted the need to deliver Evidence-Based Practice, which we define as implementation of Evidence-Based Treatments delivered with fidelity, and with the integration of important cultural, systems, and community factors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant No. R21MH082712 (Kataoka), P30MH082760 (Wells), R34MH077872 (Novins) R01DA022238 (Novins) from the National Institutes of Health and SM59285 (Wong) from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Reference list

- 1.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. In: Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in Health Care (with CD) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, editor. The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity- A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Treatment. Evidence-based practice in psychology. Am Psychol. 2006;61:271–285. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stork E, Scholle S, Greeno C, et al. Monitoring and enforcing cultural competence in Medicaid managed behavioral health care. Ment Health Serv Res. 2001;3:169. doi: 10.1023/a:1011575632212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall G. Psychotherapy research with ethnic minorities: empirical, ethical, and conceptual issues. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:502–10. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miranda J, Bernal G, Lau AS, et al. State of the science on psychosocial interventions for ethnic minorities. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:113–142. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm. Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders: Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions: Quality Chasm Series. The National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernal G. Intervention development and cultural adaptation research with diverse families. Fam Process. 2006;45:143–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Botvin GJ, Baker E, Dusenbury L, et al. Long-term follow-up results of a randomized drug abuse prevention trial in a white middle-class population. JAMA. 1995;273:1106–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harachi T, Catalano R, Hawkins J. Effective recruitment for parenting programs within ethnic minority communities. Child Adolesc Social Work J. 1997;14:23–39. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szapocznik J, Santisteban D, Rio A, et al. Family effectiveness training: An intervention to prevent drug abuse and problem behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1989;11:4–27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kazdin A. Adolescent mental health: Prevention and treatment programs. American Psychologist. 1993;48:127–140. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumpfer K, Alvarado R, Smith P, et al. Cultural sensitivity and adaptation in family-based prevention interventions. Prev Sci. 2002;3:241–246. doi: 10.1023/a:1019902902119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flaskerud JH, Liu PY. Effects of an Asian client-therapist language, ethnicity and gender match on utilization and outcome of therapy. Community Mental Health Journal. 1991;27:31–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00752713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sue S, Fujino DC, Hu L, et al. Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: A test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:533–540. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeuchi DT, Sue S, Yeh M. Return rates and outcomes from ethnicity-specific mental health programs in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:638–643. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.5.638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCabe KM, Yeh M, Garland AF, et al. The GANA program: A tailoring approach to adapting parent-child interaction therapy for Mexican Americans. Educ Treat Children. 2005;28:111–129. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szapocznik J, Rio A, Perez-Vidal A, et al. Bicultural Effectiveness Training (BET): An experimental test of an intervention modality for families experiencing intergenerational/intercultural conflict. Hisp J Behav Sci. 1986;8:303–330. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau AS. Making the case of selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13:295–310. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ngo V, Langley AK, Kataoka SH, et al. Providing evidence-based practice to ethnically diverse youths: examples from the Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) program. J Am Acad of Child and Adolesc Psychaitry. 2008;47:858–862. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181799f19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kataoka SH, Fuentes S, O’Donoghue VP, et al. A community participatory research partnership: The development of a faith-based intervention for children exposed to violence. Ethn Dis. 2006;16:S89–S97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82:581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barlow A, Varipatis-Baker E, Speakman K, et al. Home-visiting intervention to improve child care among American Indian adolescent mothers: a randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:1101–1107. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.11.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarche M, Spicer P. Poverty and health disparities for American Indian and Alaska Native children: current knowledge and future prospects. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136:126–136. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kennard BD, Silva SG, Tonev S, et al. Remission and recovery in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): acute and long-term outcomes. J Am Acad of Child and Adolesc Psychaitry. 2009;48:186–195. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819176f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weisz JR, McCarty CA, Valeri SM. Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:132–149. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad of Child and Adolesc Psychaitry. 2007;46:1503–1526. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318145ae1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mufson L, Dorta KP, Wickramaratne P, et al. A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:577–584. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mufson L, Weissman MM, Moreau D, et al. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:573–579. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.6.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossello J, Bernal G. The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal treatments for depression in Puerto Rican adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:734–745. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diamond G, Brendali R, Diamond GM, et al. Attachment-based family therapy for depressed adolescents: a treatment development study. J Am Acad of Child and Adolesc Psychaitry. 2002;41:1190–1196. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernal G, Shapiro E. In: Cuban Families in Ethnicity and Family Therapy. McGoldrick M, Giordano J, Pearce JK, editors. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falicov C. In: Mexican Families in Ethnicity and Family Therapy. McGoldrick M, Giordano J, Pearce JK, editors. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia-Preto N. In: Puerto Rican Families in Ethnicity and Family Therapy. McGoldrick M, Giordano J, Pearce JK, editors. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossello J, Bernal G, Rivera-Medina C. Individual and group CBT and IPT for Puerto Rican adolescents with depressive symptoms. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2008;14:234–245. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asarnow JR, Jaycox LH, Duan N, et al. Effectiveness of a quality improvement intervention for adolescent depression in primary care clinics: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:311–319. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ngo VK, Asarnow JR, Lange J, et al. Outcomes for youths From racial-ethnic minority groups in a quality improvement intervention for depression treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1357–1364. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.10.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kendall P. Treating anxiety disorders in children: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:100–110. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kendall P, Southam-Gerow M. Long term follow-up of a cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:724–730. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kendall PC, Flannery-Schroeder E, Panichelli-Mindel SM, et al. Therapy for youths with anxiety disorders: a second randomized clincal trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:366–380. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spence S, Donovan C, Brechman-Toussaint M. The treatment of childhood social phobia: The effectiveness of a social skills training-based, cognitive-behavioural intervention, with and without parental involvement. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:713–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silverman W, Kurtines W, Ginsburg G, et al. Treating anxiety disorders in children with group cognitive-behavioral therapy: A randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:995–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ginsburg G, Drake K. School-based treatment for anxious African-American adolescents: a controlled pilot study. J Am Acad of Child and Adolesc Psychaitry. 2002;41:768–775. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson N, Rotter J. Anxiety management training and study skills counseling for students on self-esteem and test anxiety and performance. School Counselor. 1986;34:18–31. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:414–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stein BD, Kataoka S, Jaycox LH, et al. Theoretical basis and program design of a school-based mental health intervention for traumatized immigrant children: a collaborative research partnership. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2002;29:318–326. doi: 10.1007/BF02287371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Kataoka SH, et al. A mental health intervention for schoolchildren exposed to violence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:603–611. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, et al. A school-based mental health program for traumatized Latino immigrant children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:311–318. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lieberman AF, Van Horn P, Ippen CG. Toward evidence-based treatment: child-parent psychotherapy with preschoolers exposed to marital violence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:1241–1248. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000181047.59702.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Summary of the practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with conduct disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1482–1485. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199710000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Boggs SR. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37:215–237. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Borduin CM, Mann BJ, Cone LT, et al. Multisystemic treatment of serious juvenile offenders: long-term prevention of criminality and violence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:569–578. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Henggeler SW, Clingempeel WG, Brondino MJ, et al. Four-year follow-up of Multisystemic Therapy with substance-abusing and substance dependent juvenile offenders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:868–874. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henggeler SW, Melton GB, Brondino MJ, et al. Multisystemic therapy with violence and chronic juvenile offenders and their families: the role of treatment fidelity in successful dissemination. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:821–833. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Henggeler SW, Melton GB, Smith LA. Family preservation using multisystemic therapy: an effective alternative to incarcerating serious juvenile offenders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:953–961. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lochman JE, Wells KC. Effectiveness of the coping power program and of classroom intervention with aggressive children. Behav Ther. 2003;34:493–515. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lochman JE, Wells KC. The Coping Power Program for preadolescent aggressive boys and their parents: outcomes effects at the 1-year follow-up. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:571–578. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Azrin NH, Donohue B, Teichner GA, et al. A controlled evaluation and description of individual-cognitive problem solving and family-behavior therapies in dually-diagnosed conduct-disordered and substance-dependent youth. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2001;11:1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, et al. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) study: main findings from two randomized trials. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Henggeler SW, Pickrel SG, Brondino MJ. Multisystemic treatment of substance abusing and dependent deliquents: outcomes, treatment fidelity, and transportability. Ment Health Serv Res. 1999;1:171–184. doi: 10.1023/a:1022373813261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liddle H, Dakof G, Parker K, et al. Multidimensional family therapy for adolescent drug abuse: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27:651–687. doi: 10.1081/ada-100107661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liddle H, Rowe C, Dakof G, et al. Early intervention for adolescent substance abuse: pretreatment to posttreatment outcomes of a randomized clinical trial comparing multidimensional family therapy and peer group treatment. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2004;36:49–63. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2004.10399723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liddle HA, Dakof GA, Turner RM, et al. Treating adolescent drug abuse: a randomized trial comparing multidimensional family therapy and cognitive behavior therapy. Addiction. 2008;103:1660–1670. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Slesnick N, Prestopnik JL, Meyers RJ, et al. Treatment outcome for street-living, homeless youth. Addict Behav. 2007;32:1237–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fass S, Cauthen NK. Who are America’s poor children? The official story. National Center for Children in Poverty; 2008. Edited by. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jaycox LH, Cohen J, Mannarino A, et al. Children’s mental health care following Hurricane Katrina: a field trial of trauma-focused psychotherapies. J Trauma Stress. doi: 10.1002/jts.20518. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kataoka SH, Nadeem E, Wong M, et al. Improving disaster mental health care in schools: a community-partnered approach. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:S225–S229. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wells KB, Jones L. Commentary: “Research” in community-partnered, participatory research. JAMA. 2009;302:320–321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chung B, Dixon ELJ, et al. Using a community partnered participatory research approach to implement a randomized controlled trial: planning the design of Community Partners in Care to improve the fit with the community. J Health Care Poor Underserved. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0345. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jaycox LH, Langley AK, Stein BD, et al. Support for Students Exposed to Trauma: a pilot study. School Mental Health. 2009;1:49–60. doi: 10.1007/s12310-009-9007-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huey SJ, Polo AJ. Evidence–based psychosocial treatments for ethnic minority youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37:262–301. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]