Latino young people are significantly more likely to be obese than their non-Latino white peers.1–3 Higher obesity rates place Latino young people—one of the largest, fastest-growing ethnic groups in the United States—at a heightened risk for developing a range of chronic diseases, including obesity, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and type 2 diabetes.4–8 Moreover, Latinos are far from meeting the recommended daily intake of fruit and vegetables,9–12 which is a critical public health concern considering that maintaining a healthful diet, including fruit and vegetables, is a key strategy for preventing chronic disease.13–21

The food environment influences dietary behavior. However, social and economic factors lead to stark variations in the composition and quality of food among communities that help explain disparities in dietary practices and health outcomes.22–28 Specifically, low-income communities of color have less access to fresh, affordable fruit and vegetables than more affluent communities.25,26,29–31 Furthermore, low-income, racial/ethnic minority families often find it easier to purchase energy-dense foods (characterized as high in fat, calories, and sugar) than healthier options, such as fresh fruit and vegetables.25,29,32–34 One such example is East Los Angeles (East LA), an urban, predominantly Mexican-American community that has limited access to affordable, healthful food, but an abundance of fast-food restaurants and other sources of unhealthful food.35,36 The food environment is one factor that helps explain why East LA residents experience higher rates of heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, and stroke than residents of more affluent LA neighborhoods.37

Converting corner stores to improve access to affordable, healthful foods is one potential strategy to improve the food environment.28,34,38–44 There is no one definition, or approach, for conducting corner store conversions. However, common strategies include improving the store's façade and installing refrigeration units to store the newly available fresh produce.44 The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Center for Population Health and Health Disparities (CPHHD) implemented a community-engaged corner store conversion project called Proyecto MercadoFRESCO (Fresh Market Project) in East LA and the neighboring community of Boyle Heights. This intervention converted four locally owned corner stores with the goal of increasing access to healthful food and reducing CVD risk. The CPHHD approach emphasized collaboration among community residents and organizations, public health agencies, local public schools, and store owners.44–47 The process included moving less healthful food items (i.e., chips, soda, and candy) to the back of the store, installing a fresh produce section at the front, improving the interior and exterior store façade, replacing alcohol and tobacco advertisements with healthful food messages, and providing business skills training to store owners.

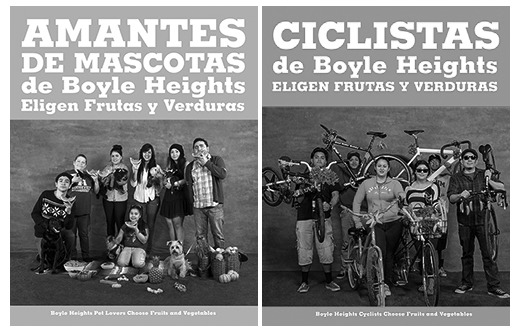

A major supplement to the conversion was a youth-driven campaign of community nutrition education and social marketing to promote the converted stores and increase the purchase of fruit and vegetables.45–47 An elective course was implemented at two public high schools, one in East LA and one in Boyle Heights, to build the capacity of local students to lead the community social marketing campaign. Students received classroom and field training in nutrition, food justice, media production, and social marketing. The campaign consisted of the following activities: performances at schools, community centers, and parks; short videos on buses; the design and dissemination of posters at bus shelters and marketing materials in neighborhoods surrounding converted stores; and cooking demonstrations at the stores (Photos 1 and 2). In addition to leading the social marketing campaign, young people were actively involved in the stores' physical transformation.

The importance of youth perspectives in implementing policy advocacy, social marketing, and health projects has been well established in tobacco and substance use prevention.48–54 While some reports document the engagement of low-income, minority young people in advocating for improvements in their access to healthful food, few reports focus on corner store interventions, and none use qualitative data to examine the perspectives of Latino young people.55–59 We sought to inform youth engagement activities related to corner store interventions through qualitative research that describes young people's perceptions of their food environment, perceptions and involvement with the market conversion project, and leadership development. This research may prove helpful to other public health interventionists seeking to mobilize young people in corner store conversions and other community-engaged efforts to improve the food environment.

METHODS

Participants

Three focus groups with 30 participants total (54% of the total number of students) were conducted with teens aged 16–17 years enrolled in an elective course, “Market Makeovers and Social Marketing,” at two public high schools. Signed assent and consent forms were obtained from the participants and their parents. Participants were recruited from June 2011 to December 2012 during after-school informational sessions.

Procedures

Focus group interviews lasted 60 minutes and were conducted in English by trained moderators. Participants completed a one-page demographic questionnaire. The discussions were audiotaped and field notes were taken. A semistructured focus group format with open-ended questions assessed the teens' perceptions of their food environment, their role and view of the market conversion, leadership development, and recommendations for sustaining the intervention and engaging young people. Thematic saturation was reached by the third focus group.

Data analysis

Audiotapes were transcribed verbatim and field notes were summarized and analyzed. Research staff verified transcriptions by listening to the tapes while reading the transcripts and identified and coded themes through content analyses. Data were analyzed by integrating both inductive (i.e., interviewee-generated categories) and deductive (i.e., interviewer-generated categories) analyses.60–62 Related codes were then linked to capture broad views of the participants. A second reviewer independently identified themes to control potential bias. There was high concordance among the reviewers.

RESULTS

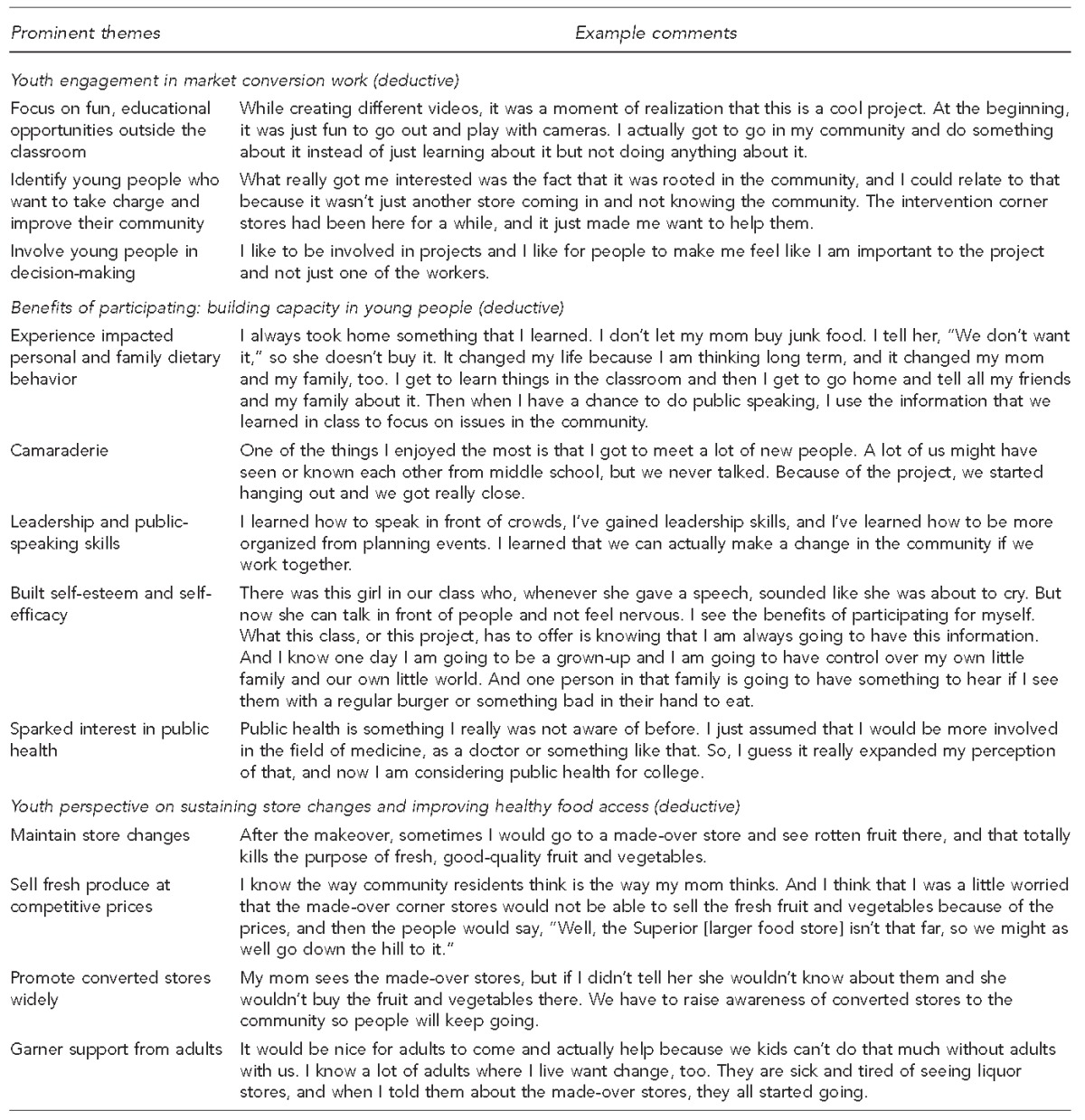

Several themes emerged focusing on young people's perceptions of their food environment, community engagement of young people, capacity building, and recommendations for sustaining the market conversion work (Table 1).

Table 1.

Focus group themes and comments about health disparities and the community food environment among Latino teens (n=30) participating in a corner store makeover project in East Los Angeles and Boyle Heights, California, 2011–2012

LA = Los Angeles

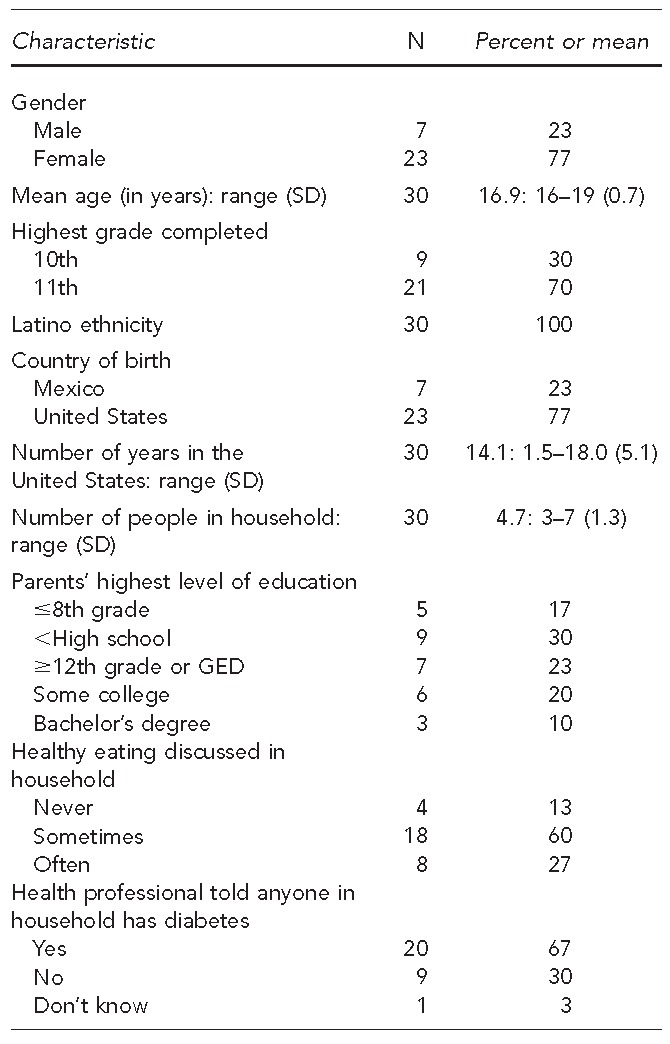

Participant demographic characteristics

Twenty-three participants were female high school seniors, 23 participants were born in the United States, the mean age of participants was 16.9 years, and participants spent a mean of 14.1 years of their life in the United States. The majority of participants' parents (n=14) had not completed high school. Eight participants reported that nutrition and healthful eating were often discussed at home, and 20 participants reported living with someone who had been told by a doctor they had diabetes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographics of Latino teens (n=30) participating in a corner store makeover project in East Los Angeles and Boyle Heights, California, 2011–2012

SD = standard deviation

GED = general educational development

Perspectives of the community food environment and the relationship between socioeconomic status and access to healthful food

Students regarded their community food environment as critical to healthful eating. All students clearly stated that there is unequal access to healthful food in LA County and commented on the variation in food environments across neighborhoods. For example, they explained that some neighborhoods are less conducive to healthful eating because of limited access to affordable, healthful food, yet easy access to fast food and alcohol. They indicated that other neighborhoods have more health-promoting factors, such as available, high-quality, affordable produce at grocery stores (e.g., Whole Foods and Trader Joe's). They added that shopping for healthier grocery items is challenging in East LA, as many residents lack transportation and find it difficult to carry items on crowded buses along multiple routes. Moreover, students recognized that East LA has higher rates of CVD, diabetes, obesity, and high cholesterol than more affluent neighborhoods.

Students were asked to describe their community food environment in general. However, students themselves identified and articulated the strong role of socioeconomic status in this matter. Several participants reasoned that differences in race/ethnicity and socioeconomic factors underlie inequities in access to healthful food. Many students argued that healthful food is more available in affluent neighborhoods, where residents are perceived to have more economic and political clout to influence their environment.

The home environment: family norms and dietary behavior

Although the home environment was not explicitly included in the focus group questions, the students frequently raised this topic as influential in their dietary practices. Students emphasized the role of family in shaping dietary behavior and explained that healthier eating is easier if the entire family participates. Some students added that they were challenged by their parents' preferences for large portion sizes and Mexican dishes cooked with lard. Others recognized that their families' tastes and preferences were reflective of the less healthful fare that is readily available at fast-food restaurants and liquor stores in their community. In addition, students inadvertently discussed dietary -acculturation, as some students asserted that relatives who had been in the United States for a shorter period of time placed more emphasis on eating fruit and vegetables than did family members who had been in the United States longer. Participants perceived financial and time constraints as factors influencing their families' diets. Thus, the students explained that as their families struggled financially, they tended to consume more quick, low-cost, unhealthy foods.

Engaging young people in market conversion work

Students initially became involved in the corner store project because they thought it would be fun to learn how to use cameras and make videos. Gradually, however, video production became a catalyst for the students to become invested in improving their food environment. The process of making videos helped students realize the reality of food justice issues in their families and neighborhoods. Over time, students developed a personal connection to the topic that cultivated a commitment to making changes in the community. The students said that their potential to make long-term changes in their community is what helped sustain their involvement in the project.

They felt ownership and pride in knowing their views contributed to the marketing campaign. Thus, it was a challenge for some students when they perceived that they were not included in some decision-making processes. Moreover, some students were confused about how their input was incorporated into the final editing process of marketing materials. In response, participants suggested that young people's involvement could be enhanced by directly involving them in key decisions. While they acknowledged the need for adult guidance on technical matters related to social marketing, students emphasized the importance of integrating their own ideas despite their lack of professional training.

Sustaining store changes and improving healthful food access

Students were not entirely convinced that increasing access to healthful food at corner stores would improve healthful eating in East LA. This finding was largely due to the fact that corner stores are commonly perceived as expensive stores full of junk food and alcohol that are used for emergencies only. Moreover, students expressed concern about the maintenance of the store changes, particularly regarding the pricing, quality, and display of fresh produce. However, students acknowledged that converted stores do indeed have the potential to make positive changes, especially at stores in convenient locations that are locally owned and run by friendly, familiar faces.

From the students' perspective, low levels of awareness about the corner store conversions and the newly available produce at the stores among community residents was compromising patronage at the recently converted stores and thereby, the conversions' sustainability. Thus, students explained that their concern about low levels of awareness of the conversions and how it could be detrimental to the adoption of healthful eating habits and the project's sustainability largely motivated their commitment to boosting social marketing efforts to promote the stores to their families and their community.

Benefits of participating: youth capacity building

Students described how the project gave them an opportunity to develop leadership, public-speaking, and organizational skills. These opportunities increased their confidence in communicating nutrition knowledge to their peers, families, and the community. As a result of their participation, the students explained how the project also improved nutrition knowledge and dietary behaviors within their families. Several students attested that their training influenced the healthfulness of their family's grocery shopping, cooking, and eating practices. Students expressed a desire to sustain these healthy behavior changes throughout adulthood and when they became parents themselves. Building camaraderie and new friendships was a common unanticipated benefit students described. As several participants explained, they had attended similar schools for years but never spoken to each other, yet they became close friends as a result of the project.

The project also influenced students' educational and career plans. For some students, it reinforced preexisting career goals in medicine or public relations; for others, the project introduced them to new fields such as public health, nursing, and graphic design. The project provided students with mentorship and technical assistance on college applications from UCLA graduate students. Due to the practical and life skills garnered through project participation, many graduating seniors enrolled in college, becoming the first in their family to seek education beyond high school. In addition, some students have been hired as field interviewers for the project's ongoing data collection and/or mentors for younger students.

DISCUSSION

The two primary purposes of this study were to (1) ascertain young people's perceptions of their food environment and (2) describe and examine the students' experience with the corner store conversion to inform future campaigns to improve the community food environments.

One strength of this study was the consistency of our findings with the existing literature. As reflected in prior studies, the students recognized that dietary habits are shaped by social and environmental factors, including household norms and behaviors, transportation, availability of healthful food, convenience, and cost.28,63–66 A common theme in the focus groups was the lack of access to healthful food coupled with an abundance of affordable, unhealthy food.57 Students also recognized that neighborhoods are segregated by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic factors, and this segregation creates disparities in access to higher-quality, more healthful foods. Consistent with previous focus group studies, our participants understood the role these environmental factors play in negatively impacting their community's dietary behaviors and health outcomes.65,66

Food availability, convenience, cost, and time barriers were cited as factors influencing eating habits at home. Participants reported that work schedules often led parents to choose less healthful family meals from fast-food restaurants rather than prepare more healthful meals at home.67,68 They were also aware of the impact of family norms and behaviors on healthful eating. For example, participants suggested that it was more difficult to eat healthfully among family members who had been in the United States for a long time and when the family members were not invested in improving their dietary habits.68,69 Despite these barriers, participants credited the project with enhancing their ability to effectively communicate and lead positive changes in dietary practices at home. Some students said that their own healthy role modeling resulted in their entire family becoming invested in more healthful eating habits.

Participants cited multiple benefits of the project's youth engagement activities. The opportunity to learn video production and work with cameras was particularly appealing. This method of engaging young people as change agents aligns with other youth-friendly participatory research methods such as photovoice and community mapping.70–72 Youth-engaged media work served to increase awareness of health disparities and introduce students to community assessment and action. In the process of identifying community health issues and interpreting their findings, students became invested in realizing positive changes in their community. Their sense of ownership was expressed by their desire to maintain the changes at converted stores. Participants also described how the project helped them develop leadership and public-speaking skills that resulted in increased self-efficacy and confidence in advocating for changes within their families and community. These outcomes are similar to what have been identified by other youth-engaged participatory research efforts,57,63,73 thus reinforcing the unique opportunities a youth-focused approach to research has for building capacity and mobilizing community members on health issues.

A unique characteristic of the CPHHD initiative was an emphasis on building local capacity and providing training and professional opportunities. The project's youth engagement component was designed not only to increase the students' knowledge of public health issues, but also to help them develop the skills necessary to continue being health advocates and to help sustain the project's efforts beyond the elective course. For example, students were not only motivated to improve their own eating habits, but were also provided training on how to initiate behavior change among their peers and relatives. The project also carried out various efforts to help sustain youth engagement upon their graduation, including internships and paid opportunities that helped continue and expand the marketing and community nutrition education efforts. Developing strong partnerships with local high schools and community-based organizations facilitated these efforts.

Limitations

This study was subject to two limitations. First, the generalizability of these results was limited to our convenience sample of primarily female high school students living in a low-income, Mexican-American community. Second, given that the study objective was to ascertain the perceptions of the young people involved in a corner store conversion project, this study did not include an assessment of community-level behavioral change as a result of the youth-engagement component. This limitation identified a current gap in the literature that future studies can help address.

CONCLUSIONS

This study adds to the growing body of literature on how young people perceive the role of social and -physical environmental factors in community health, as well as how they can be directly engaged in addressing them. This study provides young people's perspectives on how to effectively engage and sustain their involvement in corner store interventions to improve the food environment and facilitate positive changes in dietary behavior. These findings might prompt future funding and policy initiatives to develop youth-engaged components for community-level efforts, particularly efforts that focus on building local capacity and providing professional development opportunities. Such efforts not only help sustain the skills that young people develop, but can also facilitate the projects' sustainability.

Photo 1.

Students transforming the exterior of a local corner store in East Los Angeles, California, before (above) and after (below) conversion. Photo by Public Matters, LLC

Photo 2.

Two of 45 bilingual (Spanish and English) bus shelter posters, designed by high school students, installed throughout East Los Angeles and Boyle Heights to promote healthy eating. Photo by Marlene Franco

Left: Boyle Heights pet lovers choose fruit and vegetables. Right: Boyle Heights cyclists choose fruit and vegetables.

Footnotes

This study was supported by grant #P50HL105188 and grant #R25HL108854 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health. The project described was partially supported by Award #5T32AG033533 and R24H0041022 from the National Institute on Aging. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health. The Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) approved this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Flegal KM, Ogden CL, Carroll MD. Prevalence and trends in overweight in Mexican-American adults and children. Nutr Rev. 2004;62(7 Pt 2):S144–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:806–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:483–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Adolescent and school health: childhood obesity facts [cited 2014 Mar 10] Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/obesity/facts.htm.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Diabetes in youth [cited 2014 Mar 10] Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/projects/diab_children.htm.

- 6.Freedman DS, Mei Z, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS, Dietz WH. Cardiovascular risk factors and excess adiposity among overweight children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Pediatr. 2007;150:12–7.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G, Mokdad AH. Prevalence of pre-diabetes and its association with clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors and hyperinsulinemia among U.S. adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:342–7. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.BeLue R, Francis LA, Colaco B. Mental health problems and overweight in a nationally representative sample of adolescents: effects of race and ethnicity. Pediatrics. 2009;123:697–702. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Dietary guidelines for Americans [cited 2013 Nov 9] Available from: URL: http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines.

- 10.Grimm KA, Blanck HM. Survey language preference as a predictor of meeting fruit and vegetable objectives among Hispanic adults in the United States, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beech BM, Rice R, Myers L, Johnson C, Nicklas TA. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to fruit and vegetable consumption of high school students. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24:244–50. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li R, Serdula M, Bland S, Mokdad A, Bowman B, Nelson D. Trends in fruit and vegetable consumption among adults in 16 US states: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 1990–1996. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:777–81. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.5.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flock MR, Kris-Etherton PM. Dietary guidelines for Americans 2010: implications for cardiovascular disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2011;13:499–507. doi: 10.1007/s11883-011-0205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Appel LJ, Sacks FM, Carey VJ, Obarzanek E, Swain JF, Miller ER, 3rd, et al. Effects of protein, monounsaturated fat, and carbohydrate intake on blood pressure and serum lipids: results of the OmniHeart randomized trial. JAMA. 2005;294:2455–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.19.2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1117–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704173361601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obarzanek E, Sacks FM, Vollmer WM, Bray GA, Miller ER, 3rd, Lin PH, et al. Effects on blood lipids of a blood pressure-lowering diet: the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:80–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bazzano LA, Serdula MK, Liu S. Dietary intake of fruits and vegetables and risk of cardiovascular disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2003;5:492–9. doi: 10.1007/s11883-003-0040-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hung HC, Joshipura KJ, Jiang R, Hu FB, Hunter D, Smith-Warner SA, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of major chronic disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1577–84. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dauchet L, Amouyel P, Dallongeville J. Fruits, vegetables and coronary heart disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:599–608. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dauchet L, Amouyel P, Dallongeville J. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Neurology. 2005;65:1193–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000180600.09719.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dauchet L, Amouyel P, Hercberg S, Dallongeville J. Fruit and vegetable consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Nutr. 2006;136:2588–93. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.10.2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laraia BA, Siega-Riz AM, Kaufman JS, Jones SJ. Proximity of supermarkets is positively associated with diet quality index for pregnancy. Prev Med. 2004;39:869–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore LV, Diez Roux AV, Nettleton JA, Jacobs DR., Jr Associations of the local food environment with diet quality—a comparison of assessments based on surveys and geographic information systems: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:917–24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rose D, Richards R. Food store access and household fruit and vegetable use among participants in the US Food Stamp Program. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:1081–8. doi: 10.1079/PHN2004648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A. The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents' diets: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1761–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zenk SN, Schulz AJ, Hollis-Neely T, Campbell RT, Holmes N, Watkins G, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake in African Americans, income, and store characteristics. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheadle A, Psaty BM, Curry S, Wagner E, Diehr P, Koepsell T, et al. Community-level comparisons between the grocery store environment and individual dietary practices. Prev Med. 1991;20:250–61. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(91)90024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker RE, Block J, Kawachi I. Do residents of food deserts express different food buying preferences compared to residents of food oases? A mixed-methods analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:41. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Block JP, Scribner RA, DeSalvo KB. Fast food, race/ethnicity, and income: a geographic analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:211–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood environments: disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franco M, Diez Roux AV, Glass TA, Caballero B, Brancati FL. Neighborhood characteristics and availability of healthy foods in Baltimore. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:561–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boone-Heinonen J, Gordon-Larsen P, Kiefe CI, Shikany JM, Lewis CE, Popkin BM. Fast food restaurants and food stores: longitudinal associations with diet in young to middle-aged adults: the CARDIA study. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1162–70. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mari Gallagher Research & Consulting Group. Examining the impact of food deserts on public health in Chicago. Chicago: Mari Gallagher Research & Consulting Group; 2006. Also available from: URL: http://www.marigallagher.com/site_media/dynamic/project_files/1_ChicagoFoodDesertReport-Full_.pdf [cited 2013 Nov 9] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cannuscio CC, Tappe K, Hillier A, Buttenheim A, Karpyn A, Glanz K. Urban food environments and residents' shopping behaviors. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45:606–14. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A, Poole C. Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:23–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.California Center for Public Health Advocacy. Searching for healthy food: the food landscape in California cities and counties. Davis (CA): California Center for Public Health Advocacy; 2007. Also available from: URL: http://www.publichealthadvocacy.org/RFEI/policybrief_final.pdf [cited 2013 Nov 9] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. Key indicators of health. 2013 [cited 2013 Nov 9] Available from: URL: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/docs/keyindicators.pdf.

- 38.Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O'Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:253–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glanz K, Yaroch AL. Strategies for increasing fruit and vegetable intake in grocery stores and communities: policy, pricing, and environmental change. Prev Med. 2004;39(Suppl 2):S75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bolen E, Hecht K. Neighborhood groceries: new access to healthy food in low-income communities. 2003 [cited 2013 Nov 10] Available from: URL: http://www.healthycornerstores.org/wp-content/uploads/resources/CFPAreport-neighborhoodgroceries.pdf.

- 41.Raja S, Ma C, Yadav P. Beyond food deserts: measuring and mapping racial disparities in neighborhood food environments. J Plan Educ Res. 2008;27:469–82. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bodor JN, Ulmer VM, Futrell Dunaway L, Farley TA, Rose D. The rationale behind small food store interventions in low-income urban neighborhoods: insights from New Orleans. J Nutr. 2010;140:1185–8. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.113266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gittelsohn J, Rowan M, Gadhoke P. Interventions in small food stores to change the food environment, improve diet, and reduce risk of chronic disease. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:110015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Langellier BA, Garza JR, Prelip ML, Glik D, Brookmeyer R, Ortega AN. Corner store inventories, purchases, and strategies for intervention: a review of the literature. Calif J Health Promot. 2013;11:1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ortega AN, Albert SL, Sharif MZ, Langellier BA, Garcia RE, Glik DC, et al. Proyecto MercadoFRESCO: a multi-level, community-engaged corner store intervention in East Los Angeles and Boyle Heights. J Community Health. 2015;40:347–56. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9941-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Public Matters LLC. Center for Population Health + Health Disparities [cited 2013 Nov 10] Available from: URL: http://www.publicmattersgroup.com/cphhd.

- 47.Public Matters LLC. Is there a supermamá in you? [cited 2013 Nov 10] Available from: URL: http://vimeo.com/37260234.

- 48.Ramirez AG, Velez LF, Chalela P, Grussendorf J, McAlister AL. Tobacco control policy advocacy attitudes and self-efficacy among ethnically diverse high school students. Health Educ Behav. 2006;33:502–14. doi: 10.1177/1090198106287694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ribisl KM, Steckler A, Linnan L, Patterson CC, Pevzner ES, Markatos E, et al. The North Carolina Youth Empowerment Study (NCYES): a participatory research study examining the impact of youth empowerment for tobacco use prevention. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:597–614. doi: 10.1177/1090198104268550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holden DJ, Messeri P, Evans WD, Crankshaw E, Ben-Davies M. Conceptualizing youth empowerment within tobacco control. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:548–63. doi: 10.1177/1090198104268545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holden DJ, Crankshaw E, Nimsch C, Hinnant LW, Hund L. Quantifying the impact of participation in local tobacco control groups on the psychological empowerment of involved youth. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:615–28. doi: 10.1177/1090198104268678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winkleby MA, Feighery E, Dunn M, Kole S, Ahn D, Killen JD. Effects of an advocacy intervention to reduce smoking among teenagers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:269–75. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson N, Minkler M, Dasho S, Wallerstein N, Martin AC. Getting to social action: the Youth Empowerment Strategies (YES!) project. Health Promot Pract. 2008;9:395–403. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Smoking and tobacco use: state and community resources [cited 2015 Mar 5] Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity.

- 55.Millstein RA, Sallis JF. Youth advocacy for obesity prevention: the next wave of social change for health. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:497–505. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0060-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vásquez VB, Lanza D, Hennessey-Lavery S, Facente S, Halpin HA, Minkler M. Addressing food security through public policy action in a community-based participatory research partnership. Health Promot Pract. 2007;8:342–9. doi: 10.1177/1524839906298501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoshida SC, Craypo L, Samuels SE. Engaging youth in improving their food and physical activity environments. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48:641–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gittelsohn J, Dennisuk LA, Christiansen K, Bhimani R, Johnson A, Alexander E, et al. Development and implementation of Baltimore Healthy Eating Zones: a youth-targeted intervention to improve the urban food environment. Health Educ Res. 2013;28:732–44. doi: 10.1093/her/cyt066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gittelsohn J, Suratkar S, Song HJ, Sacher S, Rajan R, Rasooly IR, et al. Process evaluation of Baltimore Healthy Stores: a pilot health intervention program with supermarkets and corner stores in Baltimore City. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11:723–32. doi: 10.1177/1524839908329118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. 4th ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5:80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tsui E, Bylander K, Cho M, Maybank A, Freudenberg N. Engaging youth in food activism in New York City: lessons learned from a youth organization, health department, and university partnership. J Urban Health. 2012;89:809–27. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9684-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dodson JL, Hsiao YC, Kasat-Shors M, Murray L, Nguyen NK, Richards AK, et al. Formative research for a healthy diet intervention among inner-city adolescents: the importance of family, school and neighborhood environment. Ecol Food Nutr. 2009;48:39–58. doi: 10.1080/03670240802575493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Evans AE, Wilson DK, Buck J, Torbett H, Williams J. Outcome expectations, barriers, and strategies for healthful eating: a perspective from adolescents from low-income families. Fam Community Health. 2006;29:17–27. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200601000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Perry C, Casey MA. Factors influencing food choices of adolescents: findings from focus-group discussions with adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:929–37. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00222-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Perry C, Story M. Correlates of fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents. Findings from Project EAT. Prev Med. 2003;37:198–208. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berge JM, Arikian A, Doherty WJ, Neumark-Sztainer D. Healthful eating and physical activity in the home environment: results from multifamily focus groups. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44:123–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ayala GX, Rogers M, Arredondo EM, Campbell NR, Baquero B, Duerksen SC, et al. Away-from-home food intake and risk for obesity: examining the influence of context. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1002–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Santo CA, Ferguson N, Trippel A. Engaging urban youth through technology: the Youth Neighborhood Mapping Initiative. J Plan Educ Res. 2010;30:52–65. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Flicker S, Maley O, Ridgley A, Biscope S, Lombardo C, Skinner HA. e-PAR Using technology and participatory action research to engage youth in health promotion. Action Res. 2008;6:285–303. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Strack RW, Magill C, McDonagh K. Engaging youth through photovoice. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5:49–58. doi: 10.1177/1524839903258015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Checkoway BN, Gutiérrez LM. Youth participation and community change. New York: Haworth Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]