Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) has been considered to be a “stealth virus” that induces negligible innate immune responses during the early phase of infection. However, recent studies with newly developed experimental systems have revealed that virus infection can be recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRR), eliciting a cytokine response that controls the replication of the virus. The molecular mechanisms by which interferons and other inflammatory cytokines suppress HBV replication and modulate HBV cccDNA metabolism and function are just beginning to be revealed. In agreement with the notion that the developmental and functional status of intrahepatic innate immunity determines the activation and maturation of the HBV-specific adaptive immune response and thus the outcome of HBV infection, pharmacological activation of intrahepatic innate immune responses with TLR7/8/9 or STING agonists efficiently controls HBV infection in preclinical studies and thus holds great promise for the cure of chronic hepatitis B. This article forms part of a symposium in Antiviral Research on “An unfinished story: from the discovery of the Australia antigen to the development of new curative therapies for hepatitis B.”

Keywords: hepatitis B virus, innate immune response, cytokine, pattern recognition receptor agonist

1. Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) was at one time considered to be a “stealth virus” that induced negligible innate immune responses during the early phase of infection. However, recent studies using newly developed experimental systems have revealed that HBV infection can be recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRR), eliciting a cytokine response that controls the replication of the virus. The molecular mechanisms by which interferons and other inflammatory cytokines suppress HBV replication and modulate cccDNA metabolism and function are just beginning to be revealed.

Current research indicates that the developmental and functional status of intrahepatic innate immunity determines the activation and maturation of the HBV-specific adaptive immune response, and thus the outcome of infection. Preclinical studies have shown that the use of TLR7/8/9 or STING agonists to activate intrahepatic innate immune responses can efficiently control HBV infection. In this paper, we update our earlier review (Chang et al., 2012) on innate immune responses to HBV infection, and show how treatment with PRR agonists holds promise for the cure of chronic hepatitis B.

2. Background: pattern recognition receptors and innate immunity

Microbial infections are initially recognized by the innate immune system to elicit immediate defense responses and to help induce long-lasting adaptive immunity. Unlike the adaptive immune system that recognizes invading microorganisms by using antigen-specific receptors generated through somatic gene rearrangement of T and B lymphocytes, the sensing of the innate immune system is mediated by groups of germline-encoded receptors that recognize the common structural and functional features of microbes, or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as bacterial and fungal cell-wall components and viral nucleic acids (Akira, Uematsu, and Takeuchi, 2006). Thus far, several classes of the innate pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (Nod)-, leucine-rich repeat–containing receptors (NLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) as well as diversified DNA receptors (Paludan and Bowie, 2013; Takeuchi and Akira, 2010), have been discovered.

The physiological role of the PRRs in microbial infections has been intensively investigated in the last decades. The general consensus is that PRR-mediated inflammatory responses not only control the multiplication and spreading of microbes before the onset of a more specific and powerful adaptive immune response (Takeuchi and Akira, 2010), but also orchestrate the activation and development of the adaptive immune response, which ultimately resolves the infection and provides long-term protection against subsequent infections (Watts, West, and Zaru, 2010). Specifically, PRRs determine the origin of the antigens recognized by the antigen receptors expressed on T and B lymphocytes, as well as determine the type of infection encountered, and instruct lymphocytes to induce the appropriate effector class of the immune response (Iwasaki and Medzhitov, 2015). Accordingly, pharmacologic activation of PRR-mediated innate immune responses has been extensively explored as one of the curative therapeutic approaches for chronic microbial infections, including chronic hepatitis B (Bertoletti and Ferrari, 2011; Bertoletti and Gehring, 2013; Kanzler et al., 2007).

3. PRR sensing of HBV infection: An update

Due to the prompt recognition of viral components by host cellular PRRs, induction of type I interferon (IFN) and IFN-stimulated genes are hallmarks of viral infections. However, unlike the case of many other viruses, IFN and other inflammatory cytokine responses could not be detected in the early phase of HBV infection in chimpanzees (Wieland et al., 2004) or humans (Dunn et al., 2009; Fisicaro et al., 2009). HBV has thus been considered as a “stealthy and cunning virus” (Wieland and Chisari, 2005). However, investigation of extremely early responses to duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV) infection in domestic ducks demonstrated that IFN-α mRNA was transiently induced in the livers of ducks between 30 min to 3 h after inoculation of the virus (Tohidi-Esfahani, Vickery, and Cossart, 2010). Although the cell types responding to DHBV remain to be determined, it is most likely the input viral component(s), but not the viral products generated during replication, that triggered the IFN response.

Studies with recently developed HBV cell culture and animal models also suggest that a HBV infection is, indeed, capable of activating PRR-mediated innate immune response under certain circumstances. For instance, Shlomai and colleagues showed that HBV infection of the micropatterning and coculturing of primary human hepatocytes with fibroblasts (MPCC) induced two distinct waves of type I and type III IFN responses: a weak early response peaked between 12 h to 48 h post infection and a strong second response peaked between day 7 to 14 post infection. Interestingly, the onset of the second wave IFN response coincided with the decline of intracellular HBV pgRNA and core DNA (Shlomai et al., 2015). PRRs and viral ligand(s) for the activation of the IFN response in the MPCC human hepatocytes remain to be determined.

Sato and colleagues also reported recently that HBV replication in HepG2 cells initiated by either HBV DNA transfection or virus infection elicited a type III, but not type I, IFN response, which peaked between 24 to 48 h post infection. Interestingly, a similar IFN response profile could also be detected in HBV infected primary human hepatocytes as well as in the livers of chimeric mice at 4 or 5 weeks after HBV infection. Further analyses revealed that the hepatic type III IFN response was induced by RIG-I mediated sensing of the 5’-ε structure of HBV pregenomic RNA (Sato et al., 2015). Ironically, treatment of HBV infected primary human hepatocytes and NTCP-expressing HepG2 cells with a HBV DNA polymerase inhibitor, lamivudine, significantly attenuated the IFN response. It remains to be determined how RIG-I recognizes pgRNA that shares common structure features of host cellular mRNA and why the type III IFN response was not detected in HBV-infected chimpanzees and humans. Nevertheless, those studies, together with the observations summarized in our previous review (Chang, Block, and Guo, 2012), suggest that infection can be detected by host cellular PRRs, and can mount an innate immune response under certain conditions. However, the pathobiological role of the different PRR pathways in HBV infection remains to be determined with more biologically relevant animal models and in-clinical studies.

4. How do inflammatory cytokines cure HBV-infected hepatocytes?

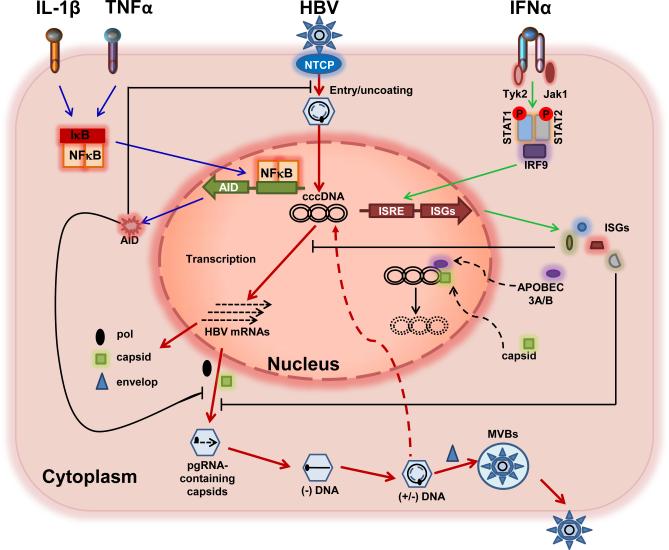

Inflammatory cytokines are major mediators of innate and adaptive immune responses. Immune clearance of HBV infection is achieved by both cytolytic T cell (CTL)-mediated killing and inflammatory cytokines induced cure of infected hepatocytes (Guidotti et al., 1996; Guidotti et al., 1999; Summers et al., 2003). Indeed, as depicted in Figure 1, it is well documented that interferons suppress HBV replication by inhibiting pgRNA encapsidation and promoting the decay of HBV nucleocapsids via unknown mechanisms (Wieland et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2010), whereas IL-1β, TNF-α and TGF-β inhibit HBV infection by induction of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) (Liang et al., 2015; Watashi et al., 2013), which restricts both early infection events and replication of HBV in a deaminase activity-independent manner (Watashi et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Interferons and other inflammatory cytokines control HBV infection of hepatocytes via multiple, distinct mechanisms. The viral replication cycle and cytokine-induced molecular pathways in hepatocytes are illustrated and explained in detail in the text. Sequential replication steps are highlighted with red lines. IFNs bind to their receptors on hepatocytes to trigger the JAK-STAT signaling pathway and induce the expression of ISGs (green lines), which control HBV replication via inhibition of pgRNA encapsidation and cccDNA transcription, as well as the elimination of cccDNA (black lines). TNF-α and IL-1β bind to their cognate receptors to activate the NF-κB pathway, inducing expression of AID (blue lines), which restricts HBV entry into hepatocytes and suppresses viral replication (black lines).

In addition to the suppression of HBV replication, elimination or transcriptional silencing of cccDNA is essential for non-cytolytic cure of HBV-infected hepatocytes, which is presumably mediated by IFN-γ, TNF-α and other cytokines (Chang et al., 2014). In fact, pegylated IFN-α is the only approved therapy that can induce a cure of chronic hepatitis B in a small (5 to 10%) but significant portion of treated patients (Perrillo, 2009). This clinical observation suggests that IFN-α may have an effect on cccDNA metabolism and/or function. Indeed, pegylated IFN-α treatment of HBV-infected chimeric mice significantly reduced the transcriptional activity of HBV cccDNA (Allweiss et al., 2013; Belloni et al., 2012; Lutgehetmann et al., 2011; Wursthorn et al., 2006). Moreover, using a chicken hepatoma cell line supporting tetracycline-inducible DHBV replication, an experimental condition that most closely mimics cccDNA-dependent DNA replication, we found that IFN-α treatment induced a prolonged suppression of cccDNA transcription and ultimate elimination of cccDNA, which were correlated with altered acetylation of cccDNA minichromosome-associated histone H3 species (Liu et al., 2013) (Figure 1).

Intriguingly, Lucifora and colleagues (Lucifora et al., 2014) reported recently that treatment of HBV-infected human primary hepatocytes or HepaRG cells with IFN-α or a lymphotoxin-β receptor (LTβR) agonist induced the expression of APOBEC3A and 3B, which were subsequently recruited into cccDNA minichromosomes by HBV core protein to catalyze cytidine deamination of cccDNA. The deaminated cccDNA was subjected for DNA repairing and ultimately degraded via unknown mechanisms (Figure 1). It will be interesting to know whether IFN-α induces cccDNA decay via a similar mechanism in human hepatocytes in vivo, and why IFN-α therapy only cures a small fraction of treated patients. Further investigation into the molecular mechanisms by which IFNs and other inflammatory cytokines modulate cccDNA metabolism and function should not only shed light on HBV pathognesis, but more importantly, provide clues for development of therapeutic strategies to eliminate or silence cccDNA.

5. Intrahepatic innate immune response determines the outcomes of HBV infection

HBV infection can be resolved within 6 months or persist for life. The single most important determining factor for the outcome of HBV infection is patient age. While over 95% of adult-acquired infections are spontaneously cleared within 6 months by a vigorous and polyclonal HBV-specific T cell response, more than 90% of exposed neonates and approximately 30% of children aged 1–5 years develop chronic infection (Lee, 1997; Liang, 2009), which is associated with a weaker and often barely detectable viral specific T cell response. In fact, the majority of the 240 million chronic carriers worldwide are due to neonatal infection. It was postulated that establishment of persistent HBV infection is due to immaturity of the neonatal immune system and/or the induction of immunotolerance. However, this hypothesis is challenged by the fact that newborns are capable of mounting a T cell response to viral infections in early life (Marchant et al., 2003; Vermijlen et al., 2010) and contradicts the clinical observation that HBV vaccination at birth efficiently protects newborns of both HBV-naïve and HBV-carrying mothers (Beasley et al., 1983; Mackie et al., 2009). Moreover, HBV-specific T cell responses were detected in two independent studies performed in HBV-negative children born from HBV-carrying mothers, suggesting that neonatal infection does not necessarily result in a persistent infection, and an efficient adaptive immune response can be elicited under selected conditions (Komatsu et al., 2010; Koumbi et al., 2010).

In an effort to understand the immune response of neonatal HBV infection, Hong and colleagues performed immunological analyses of cord blood cells from neonates of chronically infected mothers and found that HBV exposure in utero does not induce generic immunological defects, but rather triggers a state of “trained immunity,” characterized by innate immune cell maturation and a cytokine profile compatible with a Th1-like response, i.e. high levels of IL-12p40, low levels of Th2/suppressive cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-10, and a reduced proinflammatory cytokine profile (i.e. lower levels of IL-1β and IL-6) (Hong et al., 2015). However, it remains to be understood how the interesting neonatal immunological response is related to the chronicity of childhood-acquired HBV infection.

To investigate the age-dependent immune response and outcome of HBV infection, Publicover and colleagues employed a mouse model, in which HBV-transgenic mice were crossed with mice genetically deficient in the recombinase RAG1, and the immune system was reconstituted by adoptive transfer of HBV–naïve splenocytes to mimic a primary HBV infection (Publicover et al., 2011). They discovered that young mice were ineffective in the hepatic priming of a specific subset of CD4+ T cells, the T follicular helper (TFH) cells. As a result, there is a reduced production of IL-21 in the liver, which is critical for the subsequent activation of specific CD8+ T and B cell responses for the clearance of HBV antigens. In a follow-up study (Publicover et al., 2013), the authors further demonstrated that age-dependent expression of CXCL13 by adult hepatic macrophages facilitated lymphocyte trafficking, lymphoid organization and immune priming of CD4+, CD8+ T cell responses in the adult liver. In contrast, these processes are greatly diminished in the livers of young mice.

Interestingly, using a hydrodynamic injection mouse model, Chou and colleagues (Chou et al., 2015) recently found that establishment of gut microbiota correlated with the age-dependent immune clearance of HBV from hepatocytes. Specifically, while adult (12-wk-old) C3H/HeN mice cleared HBV within 6 weeks post-injection, young (6-wk-old) mice remained HBV-positive up to week 26. Sterilization of gut microbiota with antibiotics from week 6 to 12 prolonged HBV infection. Intriguingly, young mice with the TLR4 mutation (C3H/HeJ) exhibited rapid HBV clearance, suggesting that a TLR4-dependent immune tolerant pathway to HBV was induced in young mice before the establishment of gut bacteria.

While the above studies clearly indicate that the developmental and functional status of the intrahepatic innate immune system plays a critical role in the induction of adaptive immune responses against HBV infection, and thus is a key determinant of outcomes, the physiological roles of cells such as natural killer T cells (NKTs) at the interface between innate and adaptive immunity in HBV infection is just beginning to be revealed. Using a model of chronic HBV infection of immunocompetent mice established by adenovirus vector-mediated HBV (Ad-HBV) transduction, Zeissig and colleagues found that hepatocytes harboring HBV produced modified self-lipids that triggered the activation of noninvariant NKT cells directly and subsequent indirect activation of invariant NKT cells mediated via IL-12. Interestingly, the study also showed that the small HBsAg is a major contributor to Ad-HBV-mediated NKT activation, and thus suggested that NKT cells might be part of the early sensing system that leads to effective priming of HBV-specific adaptive immune responses in recognition of the presense of small HBsAg (Zeissig et al., 2012). It remains to be determined on whether HBV activation of NKT cells is age-dependent, and its role in immune activation and clearance of HBV infection.

6. Immune-modulating and antiviral activities of PRR agonists

Chronic infection occurs because the host immune system fails to eliminate pathogens and pathogen-infected cells, due to exhaustion or depletion of pathogen-specific cytotoxic effector CD8+ T cells. Therapeutic strategies aimed at increasing intrahepatic innate immunity are intended to induce not only antiviral cytokines that suppress HBV replication and non-cytolytically cure HBV-infected hepatocytes, but also correct maturation and/or recovery of exhausted HBV-specific T cells, which ultimately controls the infection. As summarized in our previous review (Chang, Block, and Guo, 2012), HBV replication can be transiently inhibited in mouse models by the agonists of many different PRRs through induction of an inflammatory cytokine response. However, their therapeutic potential, particularly effects on adaptive antiviral immune response and clinical course of HBV infection, needs to be evaluated in more biologically relevant animal models and human clinical trials.

While liver nonparenchymal cells, such as Kupffer cells, stellate cells and sinusoidal endothelial cells, express multiple TLRs that functionally respond to their cognate ligands to produce cytokines that, in turn, suppress HBV replication in hepatocytes (Guo et al., 2015; Isogawa et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2007), a recent study also demonstrated that human hepatocytes express functionally relevant levels of RIG-I, MDA5 and most of the TLRs, except for TLR7 and TLR9 (Luangsay et al., 2015). Moreover, pretreatment of HepaRG cells, which express a similar profile of PRRs as primary human hepatocytes, with different PRR agonists showed that TLR-2, TLR-4 or RIG-I/MDA-5 agonists induced the strongest antiviral response against HBV (Luangsay et al., 2015). However, as stated above, the goal of PRR agonist therapy is not only to induce an antiviral cytokine response to suppress HBV replication in hepatocytes, but more importantly to stimulate an intrahepatic HBV-specific adaptive immune response for durable control of the virus infection. It remains to be experimentally determined that therapeutic activation of which PRR(s) and in what cell type(s) will produce the most favorable clinical benefits.

6.1 TLR7 agonists

GS-9620, a potent and orally available TLR7 agonist, is the front runner of PRR agonists under development for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Its great therapeutic potential has been demonstrated in preclinical studies in woodchucks infected with woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) and HBV-infected chimpanzees. Specifically, treatment of woodchucks chronically infected by WHV with varying dose frequencies of GS-9620 for 4 to 8 weeks resulted in a greater than 6 log reduction of viral load. Intriguingly, while 15 out of 19 animals had dramatic viral load reductions during treatment, the suppressive effect on viral load was sustained in 12 of these 15 animals, and 13 of the 15 sustained WHsAg loss after cessation of treatment. Moreover, for those with sustained WHsAg loss, 8 of 13 developed an antibody against the surface antigen (Menne et al., 2015). This result is in marked contrast to treatment with nucleoside analogs and IFN-α, which rarely resulted in WHsAg seroconversion (Fletcher et al., 2012; Menne and Cote, 2007). Mechanism of action studies suggested that consistent with activation of TLR-7 signaling, the antiviral response induced by GS-9620 is likely mediated by both the cytolytic activity of CD8+ T cells and/or NK cells, and type I/II IFN-mediated non-cytolytic activity, as well as activation of B cells, in the liver microenvironment.

In a chimpanzee study, GS-9620 treatment of three HBV chronically infected animals for eight weeks also reduced viral load by more than 2 logs and resulted in greater than a 50% reduction in HBsAg and HBeAg serum levels. While reduction of viral load by 1 log persisted, no HBsAg seroconversion occurred in any of the treated animals (Lanford et al., 2013). Although IFN-α was transiently induced, the suppression of HBV /HBsAg coincided with NK/T cell activation. Hence, it is most likely that the TLR-7 therapeutic effect relies on not only induction of IFNs, but also activation of other branches of intrahepatic innate immune responses.

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies in healthy volunteers suggested that at low oral doses, GS-9620 induces a type I interferon-dependent antiviral innate immune response without the induction of systemic IFN-α. This presystemic response is likely due to its high intestinal absorption and activation of TLR7 locally via oral administration (Fosdick et al., 2014). In two phase 1b studies reported recently, one or two low doses of GS-9620 administered once a week were safe and well tolerated (Gane et al., 2015). However, phase 1 studies did not show evidence of clinical efficacy of GS-9620 in terms of HBV DNA decline, HBsAg reduction (Gane et al., 2015) or decrease in HCV RNA (Lawitz et al., 2014). Further clinical investigations are certainly warranted to optimize the dosage and treatment schedules.

6.2 TLR8 agonists

A recent report indicates that TLR8 is a more important PRR than TLR7 in human livers (Jo et al., 2014). Specifically, TLR8 agonist ssRNA40 selectively activated liver-resident, and to a lesser extent, the blood-derived, NKT mucosal-associated invariant T and CD56(bright)NK cells to produce IFN-γ in both healthy livers and HBV- or HCV-infected livers. This was mediated by the production of IL-12 and IL-18 by intrahepatic monocytes. This work thus suggests that TLR-8 agonists might be ideal candidates to activate intrahepatic immunity in patients with chronic hepatitis B (Jo et al., 2014).

6.3 TLR3 agonists

A recent report showed that intrahepatic delivery of poly(I:C), a TLR3 agonist, by hydrodynamic injection, efficiently enhanced intrahepatic innate and adaptive immune responses, and accelerated the clearance of HBV in a mouse model established by the hydrodynamic injection of pAAV-HBV1.2 (Wu et al., 2014). The clearance of HBV was dependent on both type I and type II IFNs, indicating a coordinated action of innate and adaptive immune responses. Moreover, T cell recruitment appeared to be critical for the success of TLR3-mediated antiviral action. These findings suggest that intrahepatic delivery of TLR3 agonists might have a good potential for treating chronic hepatitis B.

6.4 TLR9 agonists

The liver is an immunologically unique organ, with many layers of inhibitory mechanisms that prevent the local population expansion and execution of effector functions of CTLs. This may protect the infected liver from overwhelming immunopathology, but may also functionally compromise pathogen-specific CTLs and favor the development of chronic infection (Knolle and Thimme, 2014; Pallett et al., 2015). An elegant study reported by Knolle's laboratory recently showed that treatment of mice with the agonist of TLR9, but not TLR3 or TLR7, induced the formation of intrahepatic CD11b+MHCII+ myeloid cell aggregates, designated by the authors as “intrahepatic myeloid-cell aggregates for T cell population expansion” (iMATEs), that support massive expansion of the CTL population locally in the liver (Huang et al., 2013). The iMATEs rapidly formed within 2 days after TLR9 agonist injection and provided an anatomic structure for local proliferation of CTLs dependent on the T-cell costimulatory receptor OX40.

Intriguingly, acute but not chronic lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection induced intrahepatic iMATEs formation. However, TLR9 agonist treatment of mice chronically infected with LCMV resulted in iMATEs formation and expansion of virus-specific CLTs and subsequent control of infection. Furthermore, using a model of chronic HBV infection of immunocompetent mice established by Ad-HBV infection (Huang et al., 2012), the authors showed that injection of TLR9 agonist at day 12 after vaccination with a plasmid expressing HBcAg resulted in expansion of the H-2Kb-restricted CTL population specific for HBcAg amino acids 93–100 (HBc93) in the livers of the mice. The antiviral immune response reduced HBV antigeniemia and eventually eliminated HBV-replicating hepatocytes (Huang et al., 2013). This work implies that a combination of DNA vaccination and TLR9 agonist therapy induces intrahepatic iMATEs-facilitated expansion of the vaccination-induced HBV-specific CTL population, which subsequently resolves chronic HBV infection.

6.5 STING agonists

Stimulator of interferon genes (STING) is the adaptor protein of multiple cytoplasmic DNA receptors and a PRR recognizing the bacterial second messengers, cyclic di-adenosine monophosphate (c-di-AMP) and cyclic di-guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) (Burdette and Vance, 2013). It was discovered recently that cytoplasmic DNA activates cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate synthase (cGAS) to produce cGAMP, which subsequently binds to STING and induces IFNs and other cytokines (Gao et al., 2013; Ishikawa and Barber, 2008). The fact that STING can be activated by cyclic di-nucleotides implies that like TLR7 and TLR8, STING might be activated by other small molecules and thus be a potential target for pharmacological activation of innate immune responses, as well as priming of an adaptive immune response.

Indeed, we recently showed that 5,6-Dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA), a mouse STING agonist, induced a type I-IFN-dominant cytokine response in macrophages, which potently suppressed HBV replication in mouse hepatocytes by reducing the amount of cytoplasmic viral nucleocapsids. Moreover, intraperitoneal administration of DMXAA significantly induced the expression of IFN-stimulated genes and reduced HBV DNA replication intermediates in the livers of HBV-hydrodynamically injected mice. Our study thus provides proof of concept that activation of the STING pathway induces a potent innate antiviral response, and that the development of small-molecule human STING agonists as immunotherapeutic agents for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B is warranted (Guo et al., 2015).

Many PRR agonists have thus far been tested in animal models or in clinical studies for their effects on chronic viral infections of the liver, including hepatitis B. Although promising results have been obtained, the search for the proper agonists that fine-tune host immune responses and cure chronic HBV infection is still under way. In addition, there are many studies reporting HBV evasion and antagonization of innate immune pathways under certain experimental conditions (reviewed in (Chang, Block, and Guo, 2012)). Further investigation is required to re-examine such phenomena in the context of viral replication and in human hepatocytes during natural infection. If confirmed, pharmacological interruption of HBV antagonism of host innate immune responses should be an ideal therapeutic strategy to restore innate, and possibly also adaptive immunity to HBV infection.

7. PRR agonists as adjuvants for therapeutic vaccination

Complementary or alternative to conventional therapeutic approaches, the induction of functional antiviral immune responses in chronic HBV carriers through vaccination has been extensively explored during the past few decades (Bertoletti and Gehring, 2009). Vaccination strategies, including the conventional HBsAg vaccine, immunocomplexes of HBsAg and human anti-HBs, apoptotic cells that express HBV antigens, DNA vaccines or viral vectors expressing HBV proteins, have been evaluated in animal models and clinical trials, either alone or in combination with antiviral therapeutics, immune-stimulatory cytokines or modulators of T-cell function (Bertoletti and Gehring, 2013; Godon et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014b; Xu et al., 2013). Although a measurable antiviral immune response could be induced under selected experimental conditions, vaccination strategies that induce an immune response capable of resolving or durably controlling chronic HBV infection remain to be discovered (Liu et al., 2014a). However, promising results have emerged from recent studies in animal models, particularly the combination of a DNA-prime, adenovirus-boost immunization with entecavir therapy, which elicited sustained control of chronic WHV infection in woodchucks (Kosinska et al., 2013).

A principal barrier to the development of effective vaccines is the availability of adjuvants and formulations that can elicit both effector and long-lived memory CD4 and CD8 T cells. An additional challenge for therapeutic vaccination of chronic viral infections is overcoming host immune tolerance towards viral antigens. Considering the profound effects of PRR-mediated innate immunity on the activation and development of adaptive immune responses, agonists of PRRs, particularly TLR7, TLR9 and STING, have been explored as adjuvants of therapeutic vaccination. For instance, it was demonstrated that immunization with the TLR7/8 agonist CL097-conjugated HBV antigen reversed immune tolerance in HBV-transgenic mice and induced antigen-specific immune responses. TLR7/8 agonists appear to be potent adjuvants for the induction of antigen-specific Th1 responses in an immune-tolerant state (Wang et al., 2014).

Using a mouse model with sustained HBV viremia after infection with a recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) carrying a replicable HBV genome (AAV/HBV), Yang and colleagues also found that immunization with the conventional HBV vaccine in the presence of an alum adjuvant failed to elicit an immune response. However, vaccination of the mice with HBsAg plus TLR9-agonist CpG oligonucleotides induced strong antibody production and T-cell responses that cleared HBV viremia (Yang et al., 2014). Furthermore, recent clinical trials have shown that the HBV vaccine with a TLR9 agonist adjuvant (HBsAg-1018) induced significantly higher, earlier, and more durable seroprotection than the conventional HBV vaccine in healthy volunteers and in patients with chronic kidney disease, who are commonly hyporesponsive to HBV vaccines (Heyward et al., 2013; Janssen et al., 2013).

Cyclic dinucleotides (CDNs), the agonists of STING, have recently been explored as possible adjuvants, with particular early success in promoting mucosal immunity to intranasal vaccines (Dubensky, Kanne, and Leong, 2013). However, parenteral immunization with cdGMP and HBsAg also elicited robust humoral responses (Gray et al., 2012). Furthermore, encapsulation of cdGMP within PEGylated lipid nanoparticles (NP-cdGMP) to redirect the adjuvant to draining lymph nodes dramatically increased CD8 T cell and anti-tumor immune responses in a mouse model (Hanson et al., 2015). Encouragingly, a recent study showed that a tumor vaccine produced with CDN ligands formulated with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GMCSF), termed STINGVAX, induced potent in vivo antitumor efficacy in multiple therapeutic models of established cancer in mice. The antitumor activity was STING-dependent and correlated with increased activation of dendritic cells and tumor antigen–specific CD8+ Tcells (Fu et al., 2015). Although waiting for experimental proof, the studies published thus far suggest that STING agonists might be promising adjuvants for therapeutic vaccination of patients with chronic hepatitis B.

8. Concluding remarks

Despite the availability of effective vaccines for the last three decades, chronic HBV infection still affects 240 million people worldwide and remains a major public health problem (Ott et al., 2012). Treatment of chronic hepatitis B patients with viral DNA polymerase inhibitors dramatically reduces the viral load, significantly improves liver function and lowers the incidence of liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma (Liaw, 2013), but fails to cure the viral infection. In fact, chronic HBV infection-related diseases still account for 600,000 deaths per year worldwide (Ott et al., 2012). It is generally accepted that durable control or a functional cure of chronic HBV infection requires restoration of host HBV-specific immune response. Among many immunotherapeutic strategies (Bertoletti and Gehring, 2013; Knolle and Thimme, 2014), intrahepatic activation of PRR-mediated innate immune response should induce not only a cytokine response to suppress HBV replication and cure infected hepatocytes, but also correct maturation and/or recovery of exhausted HBV-specific T cells, which ultimately controls HBV infection. In addition, the possibility of using TLR and STING agonists as adjuvants for therapeutic vaccination deserves further exploration. We believe that the goal of functional cure will be reached most likely by combination therapies of antiviral agents and immunotherapeutics.

CHANG Highlights Bray edits 15 July.

■ Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection can be sensed by pattern recognition receptors.

■ Interferons, TNF-α and IL-1β inhibit HBV replication via distinct mechanisms.

■ Intrahepatic innate immune responses determine the outcome of HBV infection.

■ Intrahepatic activation of TLR7/8/9 or the STING response holds great promise for the cure of chronic hepatitis B.

Acknowledgement

We thank Julia Ma for her critical reading of the manuscript. The work in our laboratories is supported in part by the NIH grant (R01AI113267) and the Hepatitis B Foundation through an appropriation from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124(4):783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allweiss L, Volz T, Lutgehetmann M, Giersch K, Bornscheuer T, Lohse AW, Petersen J, Ma H, Klumpp K, Fletcher SP, Dandri M. Immune cell responses are not required to induce substantial hepatitis B virus antigen decline during pegylated interferon-alpha administration. J Hepatol. 2013;60(3):500–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley RP, Hwang LY, Lee GC, Lan CC, Roan CH, Huang FY, Chen CL. Prevention of perinatally transmitted hepatitis B virus infections with hepatitis B immune globulin and hepatitis B vaccine. Lancet. 1983;2(8359):1099–102. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90624-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloni L, Allweiss L, Guerrieri F, Pediconi N, Volz T, Pollicino T, Petersen J, Raimondo G, Dandri M, Levrero M. IFN-alpha inhibits HBV transcription and replication in cell culture and in humanized mice by targeting the epigenetic regulation of the nuclear cccDNA minichromosome. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(2):529–37. doi: 10.1172/JCI58847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoletti A, Ferrari C. Innate and adaptive immune responses in chronic hepatitis B virus infections: towards restoration of immune control of viral infection. Gut. 2011;61(12):1754–64. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoletti A, Gehring A. Therapeutic vaccination and novel strategies to treat chronic HBV infection. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;3(5):561–9. doi: 10.1586/egh.09.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoletti A, Gehring AJ. Immune therapeutic strategies in chronic hepatitis B virus infection: virus or inflammation control? PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(12):e1003784. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdette DL, Vance RE. STING and the innate immune response to nucleic acids in the cytosol. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(1):19–26. doi: 10.1038/ni.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J, Block TM, Guo JT. The innate immune response to hepatitis B virus infection: implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Antiviral Res. 2012;96(3):405–13. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J, Guo F, Zhao X, Guo J-T. Therapeutic strategies for a functional cure of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2014;4(4):248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou HH, Chien WH, Wu LL, Cheng CH, Chung CH, Horng JH, Ni YH, Tseng HT, Wu D, Lu X, Wang HY, Chen PJ, Chen DS. Age-related immune clearance of hepatitis B virus infection requires the establishment of gut microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(7):2175–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424775112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubensky TW, Jr., Kanne DB, Leong ML. Rationale, progress and development of vaccines utilizing STING-activating cyclic dinucleotide adjuvants. Ther Adv Vaccines. 2013;1(4):131–43. doi: 10.1177/2051013613501988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn C, Peppa D, Khanna P, Nebbia G, Jones M, Brendish N, Lascar RM, Brown D, Gilson RJ, Tedder RJ, Dusheiko GM, Jacobs M, Klenerman P, Maini MK. Temporal analysis of early immune responses in patients with acute hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(4):1289–300. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisicaro P, Valdatta C, Boni C, Massari M, Mori C, Zerbini A, Orlandini A, Sacchelli L, Missale G, Ferrari C. Early kinetics of innate and adaptive immune responses during hepatitis B virus infection. Gut. 2009;58(7):974–82. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.163600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher SP, Chin DJ, Ji Y, Iniguez AL, Taillon B, Swinney DC, Ravindran P, Cheng DT, Bitter H, Lopatin U, Ma H, Klumpp K, Menne S. Transcriptomic analysis of the woodchuck model of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2012;56(3):820–30. doi: 10.1002/hep.25730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosdick A, Zheng J, Pflanz S, Frey CR, Hesselgesser J, Halcomb RL, Wolfgang G, Tumas DB. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of GS-9620, a novel Toll-like receptor 7 agonist, demonstrate interferon-stimulated gene induction without detectable serum interferon at low oral doses. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;348(1):96–105. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.207878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Kanne DB, Leong M, Glickman LH, McWhirter SM, Lemmens E, Mechette K, Leong JJ, Lauer P, Liu W, Sivick KE, Zeng Q, Soares KC, Zheng L, Portnoy DA, Woodward JJ, Pardoll DM, Dubensky TW, Jr., Kim Y. STING agonist formulated cancer vaccines can cure established tumors resistant to PD-1 blockade. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(283):283ra52. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa4306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gane EJ, Lim YS, Gordon SC, Visvanathan K, Sicard E, Fedorak RN, Roberts S, Massetto B, Ye Z, Pflanz S, Garrison KL, Gaggar A, Mani Subramanian G, McHutchison JG, Kottilil S, Freilich B, Coffin CS, Cheng W, Kim YJ. The Oral Toll-Like Receptor-7 Agonist GS-9620 in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection. J Hepatol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao D, Wu J, Wu YT, Du F, Aroh C, Yan N, Sun L, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is an innate immune sensor of HIV and other retroviruses. Science. 2013;341(6148):903–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1240933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godon O, Fontaine H, Kahi S, Meritet J, Scott-Algara D, Pol S, Michel M, Bourgine M. Immunological and antiviral responses after therapeutic DNA immunization in chronic hepatitis B patients efficiently treated by analogues. Mol Ther. 2013;22(3):675–84. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray PM, Forrest G, Wisniewski T, Porter G, Freed DC, DeMartino JA, Zaller DM, Guo Z, Leone J, Fu TM, Vora KA. Evidence for cyclic diguanylate as a vaccine adjuvant with novel immunostimulatory activities. Cell Immunol. 2012;278(1-2):113–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti LG, Ishikawa T, Hobbs MV, Matzke B, Schreiber R, Chisari FV. Intracellular inactivation of the hepatitis B virus by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunity. 1996;4(1):25–36. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti LG, Rochford R, Chung J, Shapiro M, Purcell R, Chisari FV. Viral clearance without destruction of infected cells during acute HBV infection [In Process Citation]. Science. 1999;284(5415):825–9. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F, Han Y, Zhao X, Wang J, Liu F, Xu C, Wei L, Jiang JD, Block TM, Guo JT, Chang J. STING Agonists Induce an Innate Antiviral Immune Response against Hepatitis B Virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(2):1273–81. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04321-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson MC, Crespo MP, Abraham W, Moynihan KD, Szeto GL, Chen SH, Melo MB, Mueller S, Irvine DJ. Nanoparticulate STING agonists are potent lymph node-targeted vaccine adjuvants. J Clin Invest. 2015 doi: 10.1172/JCI79915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyward WL, Kyle M, Blumenau J, Davis M, Reisinger K, Kabongo ML, Bennett S, Janssen RS, Namini H, Martin JT. Immunogenicity and safety of an investigational hepatitis B vaccine with a Toll-like receptor 9 agonist adjuvant (HBsAg-1018) compared to a licensed hepatitis B vaccine in healthy adults 40-70 years of age. Vaccine. 2013;31(46):5300–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M, Sandalova E, Low D, Gehring AJ, Fieni S, Amadei B, Urbani S, Chong YS, Guccione E, Bertoletti A. Trained immunity in newborn infants of HBV-infected mothers. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6588. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LR, Gabel YA, Graf S, Arzberger S, Kurts C, Heikenwalder M, Knolle PA, Protzer U. Transfer of HBV genomes using low doses of adenovirus vectors leads to persistent infection in immune competent mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(7):1447–50. e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LR, Wohlleber D, Reisinger F, Jenne CN, Cheng RL, Abdullah Z, Schildberg FA, Odenthal M, Dienes HP, van Rooijen N, Schmitt E, Garbi N, Croft M, Kurts C, Kubes P, Protzer U, Heikenwalder M, Knolle PA. Intrahepatic myeloid-cell aggregates enable local proliferation of CD8(+) T cells and successful immunotherapy against chronic viral liver infection. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(6):574–83. doi: 10.1038/ni.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H, Barber GN. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature. 2008;455(7213):674–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isogawa M, Robek MD, Furuichi Y, Chisari FV. Toll-like receptor signaling inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in vivo. J Virol. 2005;79(11):7269–72. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.7269-7272.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Control of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(4):343–53. doi: 10.1038/ni.3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen RS, Mangoo-Karim R, Pergola PE, Girndt M, Namini H, Rahman S, Bennett SR, Heyward WL, Martin JT. Immunogenicity and safety of an investigational hepatitis B vaccine with a toll-like receptor 9 agonist adjuvant (HBsAg-1018) compared with a licensed hepatitis B vaccine in patients with chronic kidney disease. Vaccine. 2013;31(46):5306–13. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo J, Tan AT, Ussher JE, Sandalova E, Tang XZ, Tan-Garcia A, To N, Hong M, Chia A, Gill US, Kennedy PT, Tan KC, Lee KH, De Libero G, Gehring AJ, Willberg CB, Klenerman P, Bertoletti A. Toll-like receptor 8 agonist and bacteria trigger potent activation of innate immune cells in human liver. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(6):e1004210. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzler H, Barrat FJ, Hessel EM, Coffman RL. Therapeutic targeting of innate immunity with Toll-like receptor agonists and antagonists. Nat Med. 2007;13(5):552–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knolle PA, Thimme R. Hepatic immune regulation and its involvement in viral hepatitis infection. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):1193–207. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu H, Inui A, Sogo T, Hiejima E, Tateno A, Klenerman P, Fujisawa T. Cellular immunity in children with successful immunoprophylactic treatment for mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosinska AD, Zhang E, Johrden L, Liu J, Seiz PL, Zhang X, Ma Z, Kemper T, Fiedler M, Glebe D, Wildner O, Dittmer U, Lu M, Roggendorf M. Combination of DNA prime--adenovirus boost immunization with entecavir elicits sustained control of chronic hepatitis B in the woodchuck model. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(6):e1003391. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koumbi L, Bertoletti A, Anastasiadou V, Machaira M, Goh W, Papadopoulos NG, Kafetzis DA, Papaevangelou V. Hepatitis B-specific T helper cell responses in uninfected infants born to HBsAg+/HBeAg-mothers. Cell Mol Immunol. 2010;7(6):454–8. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanford RE, Guerra B, Chavez D, Giavedoni L, Hodara VL, Brasky KM, Fosdick A, Frey CR, Zheng J, Wolfgang G, Halcomb RL, Tumas DB. GS-9620, an oral agonist of Toll-like receptor-7, induces prolonged suppression of hepatitis B virus in chronically infected chimpanzees. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(7):1508–17. 1517, e1–10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawitz E, Gruener D, Marbury T, Hill J, Webster L, Hassman D, Nguyen AH, Pflanz S, Mogalian E, Gaggar A, Massetto B, Subramanian GM, McHutchison JG, Jacobson IM, Freilich B, Rodriguez-Torres M. Safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the oral Toll-like receptor 7 agonist GS-9620 in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C. Antivir Ther. 2014 doi: 10.3851/IMP2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WM. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(24):1733–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang G, Liu G, Kitamura K, Wang Z, Chowdhury S, Monjurul AM, Wakae K, Koura M, Shimadu M, Kinoshita K, Muramatsu M. TGF-beta Suppression of HBV RNA through AID-Dependent Recruitment of an RNA Exosome Complex. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(4):e1004780. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang TJ. Hepatitis B: the virus and disease. Hepatology. 2009;49(5 Suppl):S13–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.22881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw YF. Impact of therapy on the outcome of chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int 33 Suppl. 2013;1:111–5. doi: 10.1111/liv.12057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Campagna M, Qi Y, Zhao X, Guo F, Xu C, Li S, Li W, Block TM, Chang J, Guo JT. Alpha-interferon suppresses hepadnavirus transcription by altering epigenetic modification of cccDNA minichromosomes. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(9):e1003613. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Kosinska A, Lu M, Roggendorf M. New therapeutic vaccination strategies for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Virol Sin. 2014a;29(1):10–6. doi: 10.1007/s12250-014-3410-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zhang E, Ma Z, Wu W, Kosinska A, Zhang X, Moller I, Seiz P, Glebe D, Wang B, Yang D, Lu M, Roggendorf M. Enhancing virus-specific immunity in vivo by combining therapeutic vaccination and PD-L1 blockade in chronic hepadnaviral infection. PLoS Pathog. 2014b;10(1):e1003856. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luangsay S, Ait-Goughoulte M, Michelet M, Floriot O, Bonnin M, Gruffaz M, Rivoire M, Fletcher S, Javanbakht H, Lucifora J, Zoulim F, Durantel D. Expression and Functionality of Toll- and RIG-like receptors in HepaRG Cells. J Hepatol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucifora J, Xia Y, Reisinger F, Zhang K, Stadler D, Cheng X, Sprinzl MF, Koppensteiner H, Makowska Z, Volz T, Remouchamps C, Chou WM, Thasler WE, Huser N, Durantel D, Liang TJ, Munk C, Heim MH, Browning JL, Dejardin E, Dandri M, Schindler M, Heikenwalder M, Protzer U. Specific and nonhepatotoxic degradation of nuclear hepatitis B virus cccDNA. Science. 2014;343(6176):1221–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1243462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutgehetmann M, Bornscheuer T, Volz T, Allweiss L, Bockmann JH, Pollok JM, Lohse AW, Petersen J, Dandri M. Hepatitis B virus limits response of human hepatocytes to interferon-alpha in chimeric mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(7):2074–83. 2083, e1–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie CO, Buxton JA, Tadwalkar S, Patrick DM. Hepatitis B immunization strategies: timing is everything. CMAJ. 2009;180(2):196–202. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant A, Appay V, Van Der Sande M, Dulphy N, Liesnard C, Kidd M, Kaye S, Ojuola O, Gillespie GM, Vargas Cuero AL, Cerundolo V, Callan M, McAdam KP, Rowland-Jones SL, Donner C, McMichael AJ, Whittle H. Mature CD8(+) T lymphocyte response to viral infection during fetal life. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(11):1747–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI17470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menne S, Cote PJ. The woodchuck as an animal model for pathogenesis and therapy of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(1):104–24. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menne S, Tumas DB, Liu KH, Thampi L, AlDeghaither D, Baldwin BH, Bellezza CA, Cote PJ, Zheng J, Halcomb R, Fosdick A, Fletcher SP, Daffis S, Li L, Yue P, Wolfgang GH, Tennant BC. Sustained efficacy and seroconversion with the Toll-like receptor 7 agonist GS-9620 in the Woodchuck model of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2015;62(6):1237–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott JJ, Stevens GA, Groeger J, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine. 2012;30(12):2212–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallett LJ, Gill US, Quaglia A, Sinclair LV, Jover-Cobos M, Schurich A, Singh KP, Thomas N, Das A, Chen A, Fusai G, Bertoletti A, Cantrell DA, Kennedy PT, Davies NA, Haniffa M, Maini MK. Metabolic regulation of hepatitis B immunopathology by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Nat Med. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nm.3856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paludan SR, Bowie AG. Immune sensing of DNA. Immunity. 2013;38(5):870–80. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrillo R. Benefits and risks of interferon therapy for hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009;49(5 Suppl):S103–11. doi: 10.1002/hep.22956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Publicover J, Gaggar A, Nishimura S, Van Horn CM, Goodsell A, Muench MO, Reinhardt RL, van Rooijen N, Wakil AE, Peters M, Cyster JG, Erle DJ, Rosenthal P, Cooper S, Baron JL. Age-dependent hepatic lymphoid organization directs successful immunity to hepatitis B. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(9):3728–39. doi: 10.1172/JCI68182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Publicover J, Goodsell A, Nishimura S, Vilarinho S, Wang ZE, Avanesyan L, Spolski R, Leonard WJ, Cooper S, Baron JL. IL-21 is pivotal in determining age-dependent effectiveness of immune responses in a mouse model of human hepatitis B. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(3):1154–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI44198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Li K, Kameyama T, Hayashi T, Ishida Y, Murakami S, Watanabe T, Iijima S, Sakurai Y, Watashi K, Tsutsumi S, Sato Y, Akita H, Wakita T, Rice CM, Harashima H, Kohara M, Tanaka Y, Takaoka A. The RNA sensor RIG-I dually functions as an innate sensor and direct antiviral factor for hepatitis B virus. Immunity. 2015;42(1):123–32. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlomai A, Schwartz RE, Ramanan V, Bhatta A, de Jong YP, Bhatia SN, Rice CM. Modeling host interactions with hepatitis B virus using primary and induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocellular systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;111(33):12193–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412631111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers J, Jilbert AR, Yang W, Aldrich CE, Saputelli J, Litwin S, Toll E, Mason WS. Hepatocyte turnover during resolution of a transient hepadnaviral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(20):11652–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635109100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140(6):805–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohidi-Esfahani R, Vickery K, Cossart Y. The early host innate immune response to duck hepatitis B virus infection. J Gen Virol. 2010;91(Pt 2):509–20. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015529-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermijlen D, Brouwer M, Donner C, Liesnard C, Tackoen M, Van Rysselberge M, Twite N, Goldman M, Marchant A, Willems F. Human cytomegalovirus elicits fetal gammadelta T cell responses in utero. J Exp Med. 2010;207(4):807–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chen K, Wu Z, Liu Y, Liu S, Zou Z, Chen SH, Qu C. Immunizations with hepatitis B viral antigens and a TLR7/8 agonist adjuvant induce antigen-specific immune responses in HBV-transgenic mice. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;29:31–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watashi K, Liang G, Iwamoto M, Marusawa H, Uchida N, Daito T, Kitamura K, Muramatsu M, Ohashi H, Kiyohara T, Suzuki R, Li J, Tong S, Tanaka Y, Murata K, Aizaki H, Wakita T. Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha trigger restriction of hepatitis B virus infection via a cytidine deaminase activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID). J Biol Chem. 2013;288(44):31715–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.501122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts C, West MA, Zaru R. TLR signalling regulated antigen presentation in dendritic cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22(1):124–30. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland S, Thimme R, Purcell RH, Chisari FV. Genomic analysis of the host response to hepatitis B virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(17):6669–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401771101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland SF, Chisari FV. Stealth and cunning: hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses. J Virol. 2005;79(15):9369–80. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9369-9380.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland SF, Eustaquio A, Whitten-Bauer C, Boyd B, Chisari FV. Interferon prevents formation of replication-competent hepatitis B virus RNA-containing nucleocapsids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(28):9913–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504273102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Huang S, Zhao X, Chen M, Lin Y, Xia Y, Sun C, Yang X, Wang J, Guo Y, Song J, Zhang E, Wang B, Zheng X, Schlaak JF, Lu M, Yang D. Poly(I:C) treatment leads to interferon-dependent clearance of hepatitis B virus in a hydrodynamic injection mouse model. J Virol. 2014;88(18):10421–31. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00996-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Lu M, Meng Z, Trippler M, Broering R, Szczeponek A, Krux F, Dittmer U, Roggendorf M, Gerken G, Schlaak JF. Toll-like receptor-mediated control of HBV replication by nonparenchymal liver cells in mice. Hepatology. 2007;46(6):1769–78. doi: 10.1002/hep.21897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wursthorn K, Lutgehetmann M, Dandri M, Volz T, Buggisch P, Zollner B, Longerich T, Schirmacher P, Metzler F, Zankel M, Fischer C, Currie G, Brosgart C, Petersen J. Peginterferon alpha-2b plus adefovir induce strong cccDNA decline and HBsAg reduction in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2006;44(3):675–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.21282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Guo H, Pan XB, Mao R, Yu W, Xu X, Wei L, Chang J, Block TM, Guo JT. Interferons accelerate decay of replication-competent nucleocapsids of hepatitis B virus. J Virol. 2010;84(18):9332–40. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00918-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu DZ, Wang XY, Shen XL, Gong GZ, Ren H, Guo LM, Sun AM, Xu M, Li LJ, Guo XH, Zhen Z, Wang HF, Gong HY, Xu C, Jiang N, Pan C, Gong ZJ, Zhang JM, Shang J, Xu J, Xie Q, Wu TF, Huang WX, Li YG, Yuan ZH, Wang B, Zhao K, Wen YM. Results of a phase III clinical trial with an HBsAg-HBIG immunogenic complex therapeutic vaccine for chronic hepatitis B patients: experiences and findings. J Hepatol. 2013;59(3):450–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Liu L, Zhu D, Peng H, Su L, Fu YX, Zhang L. A mouse model for HBV immunotolerance and immunotherapy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2014;11(1):71–8. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2013.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeissig S, Murata K, Sweet L, Publicover J, Hu Z, Kaser A, Bosse E, Iqbal J, Hussain MM, Balschun K, Rocken C, Arlt A, Gunther R, Hampe J, Schreiber S, Baron JL, Moody DB, Liang TJ, Blumberg RS. Hepatitis B virus-induced lipid alterations contribute to natural killer T cell-dependent protective immunity. Nat Med. 2012;18(7):1060–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]