Abstract

Objective

Cervical cancer screening using the human papillomavirus (HPV) test and Pap test together (co-testing) is an option for average-risk women ≥30 years of age. With normal co-test results, screening intervals can be extended. The study objective is to assess primary care provider practices, beliefs, facilitators and barriers to using the co-test and extending screening intervals among low-income women.

Method

Data were collected from 98 providers in 15 Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) clinics in Illinois between August 2009 and March 2010 using a cross-sectional survey.

Results

39% of providers reported using the co-test, and 25% would recommend a three-year screening interval for women with normal co-test results. Providers perceived greater encouragement for co-testing than for extending screening intervals with a normal co-test result. Barriers to extending screening intervals included concerns about patients not returning annually for other screening tests (77%), patient concerns about missing cancer (62%), and liability (52%).

Conclusion

Among FQHC providers in Illinois, few administered the co-test for screening and recommended appropriate intervals, possibly due to concerns over loss to follow-up and liability. Education regarding harms of too-frequent screening and false positives may be necessary to balance barriers to extending screening intervals.

Keywords: Cervical cancer screening, Screening guidelines, HPV testing

Introduction

Cervical cancer screening with the Papanicolaou (Pap) test has become a centerpiece of women's preventive healthcare, dramatically reducing cervical cancer incidence and mortality in the United States over the last five decades (Habbema et al., 2012). Despite widespread reduction in cervical cancer incidence and mortality, there are still marked disparities in the cervical cancer burden. Uninsured and low-income women usually are screened less often than recommended, and suffer disproportionate cervical cancer morbidity, mortality and late-stage diagnosis (Benard et al., 2008; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012a; Fedewa et al., 2012). Based on the role of persistent high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in the development of cervical cancer, newer screening technologies have changed the landscape of screening options for women (Bosch et al., 2002; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012b; Munoz et al., 1992; Walboomers et al., 1999). In 2003 the HPV test was approved for concurrent use with the Pap test (known as co-testing) for women ≥ 30 years of age (US Food and Drug Administration, 2003). The rationale for co-testing is the increased sensitivity for detecting high-grade cervical pre-cancer and cancer compared with the Pap test alone (Cuzick et al., 2008; Sherman et al., 2003). Currently, co-testing is the preferred screening approach among some professional organizations recommending screening guidelines (ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology, 2012; Saslow et al., 2012). When co-test results are normal (normal Pap test, negative HPV test), women can wait five years until their next cervical cancer screening (ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology, 2012; Saslow et al., 2012; US Preventive Services Task Force, 2012).

Despite the evidence-based recommendations for longer screening intervals, it is well documented that cervical cancer screening with the Pap test alone and co-test may occur more frequently than recommended (Holland-Barkis et al., 2006; Roland et al., 2011, 2013; Saraiya et al., 2010; Yabroff et al., 2009). In the average-risk population with routine access to care, overuse of cancer screening can cause considerable harms to patients, and undue costs to patients, providers, and healthcare systems (Bentley et al., 2008; Good Stewardship Working Group, 2011; Habbema et al., 2012; Idestrom et al., 2003; Monsonego et al., 2011). However, no studies have examined provider cervical cancer screening practices and beliefs regarding co-testing and screening intervals in a low-income, underserved population facing barriers to care. Therefore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) launched the Cervical Cancer (Cx3) Study to assess provider's cervical cancer screening knowledge, attitudes, practices, and beliefs, regarding the co-test and screening intervals to identify facilitators and barriers to acceptance and appropriate use of cervical cancer screening tests in a low-income population.

Methods

The Cx3 Study was conducted in 15 clinics associated with six Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) across Illinois. FQHCs were selected as study sites because they are safety-net providers serving individuals who disproportionately face cost and access barriers to healthcare. Illinois was selected as the study location based on the Illinois Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program's high Pap test volume, follow-up rate, and outreach activities targeting underserved women for cervical cancer screening (http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/nbccedp/data/summaries/illinois.htm), and high incidence of cervical cancer in Illinois.

Data analyzed from the baseline survey were collected between August 2009 and March 2010. Providers were eligible to participate if they personally performed Pap testing for routine screening. The self-administered surveys and a $50 cash incentive were sent to participating clinics and distributed to providers by clinic staff prior to study initiation with a stamped, self-addressed envelope for return. Clinic coordinators would follow-up weekly with non-responding providers; many were encouraged multiple times to complete the survey. The baseline survey was pilot tested with seven primary care providers in the Atlanta area to obtain an estimate of respondent burden, comments about the format, and appropriateness and relevance of survey questions. CDC's Institutional Review Board approved the study. Results are descriptive and presented as percent distributions.

Measures

The baseline provider survey was developed to assess knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices regarding cervical cancer prevention. Measures and clinical vignettes in the Cx3 Study provider baseline survey were modeled upon national primary care provider cervical cancer screening practice surveys (Benard et al., 2011; Roland et al., 2011). Both provider and their patient's demographic data were collected, as well as Pap test and HPV test screening practices, attitude, and beliefs; risk management practices; and HPV vaccine attitudes and practices. The focus of this manuscript is to report findings regarding co-testing and screening intervals only. Table 1 presents each measure included in this analysis, the corresponding question, and response options.

Table 1.

Survey measures, baseline Cx3 Study provider survey administered at 15 Federally Qualified Health Center clinics in Illinois, USA (2009–2010).

| Measure | Question | Response options |

|---|---|---|

| HPV test practices | For your female patients ≥30 years of age, how often do you use HPV testing: 1) With the Pap test for routine cervical cancer screening; and 2) as a follow-up test for an atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US) Pap test? |

Never; sometimes; half the time; usually; or always |

| Screening interval practices | For a woman 35 years of age, indicate the next cervical cancer screening interval you would be most likely to recommend for her next test given: 1) A normal Pap this visit, negative HPV test this visit; and 2) normal Pap this visit, positive HPV test this visit. |

<1 year; 1 year; 2 years; 3 years; or >3 yearsa |

| Perceived support for using the co-test | Please indicate the extent to which you feel that the following individuals or entities encourage or discourage you to conduct HPV testing along with Pap testing for routine screening in women ≥30 years of age: 1) patients; 2) colleagues; 3) administration in practice; 4) professional health organizations; 5) professional specialty organizations; and 6) professional journals | Strongly discourage; discourage; neither; encourage; or strongly encourageb |

| Perceived support for extending screening intervals | Please indicate the extent to which the following individuals or entities encourage or discourage you to extend the screening interval to 3 years between tests for women ≥30 years of age with a normal Pap result and a negative HPV test: 1) patients; 2) colleagues; 3) administration in practice; 4) professional health organizations; 5) professional specialty organizations; and 6) professional journals | Strongly discourage; discourage; neither; encourage; or strongly encourage b |

| Beliefs about co-testing | Conducting HPV testing along with Pap testing for routine screening in women ≥30 years of age is… 1) Good versus bad; 2) easy versus difficult; and 3) beneficial versus harmful. | 1) Extremely good; quite good; neither; quite bad; or extremely badc; 2) extremely easy; quite easy; neither; quite difficult; or extremely difficultd; and 3) extremely beneficial; quite beneficial; neither; quite harmful; or extremely harmfule. |

| Beliefs about screening intervals | Deciding to extend the cervical cancer screening interval to 3 or more years because a woman ≥30 years of age had received a normal Pap result and negative HPV test would be… 1) good versus bad; 2) easy versus difficult; and 3) beneficial versus harmful. | 1) Extremely good; quite good; neither; quite bad; or extremely bad; 2) extremely easy; quite easy; neither; quite difficult; or extremely difficult; 3) extremely beneficial; quite beneficial; neither; quite harmful; or extremely harmfule. |

| Factors considered when extending a woman's screening interval (with a Pap test alone or the co-test) | To what extent do you consider the following factors in deciding whether or not to extend the cervical cancer screening interval for women ≥30 years of age? 19 statements related to medical history, sexual history, exposures, behaviors, and socio-demographics. | Not at all; some; or a great deal |

| Perceived risks and benefits to extending the screening interval | For a woman ≥30 years of age with a normal Pap result and a negative HPV test, please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with the following statements about extending the screening interval to three or more years between tests. 10 statements related to perceived risk and benefits of extending the screening interval. | Strongly disagree; disagree; neither; agree; or strongly agree f |

At the time of survey (2009–2010), screening guidelines recommended a three-year screening interval with a normal co-test result, (ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology, 2009; Saslow et al., 2002) and a one-year screening interval with a normal Pap test, positive HPV test (Apgar et al., 2009).

Strongly discourage and discourage results were collapsed together, and strongly encourage and encourage results were collapsed together.

Extremely good and quite good results were collapsed together, and extremely bad and quite bad results were collapsed together.

Extremely easy and quite easy results were collapsed together, and extremely difficult and quite difficult results were collapsed together.

Extremely beneficial and quite beneficial results were collapsed together, and extremely harmful and quite harmful results were collapsed together.

Strongly disagree and disagree results were collapsed together, and strongly agree and agree results were collapsed together.

Results

Surveys were completed by 98 of 109 eligible providers (89.9% response rate). Most providers were physicians (66%), specializing in obstetrics/gynecology (53%). They reported an average of 8.8 years providing clinical care. Almost all providers reported following published guidelines for cervical cancer screening and management (94%), and 75% reported they last participated in continuing medical education for HPV testing or cervical cancer screening within the previous three years (Table 2).

Table 2.

Personal characteristics of providers who completed the baseline survey for the Cx3 Study (n = 98). (Study was conducted in 15 Federally Qualified Health Center clinics in Illinois, USA, 2009–2010).

| Number of providers |

Percent or mean ± SD |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 98 | 41.3 ± 11.4 |

| Location of clinic | ||

| Chicago | 68 | 69 |

| Outside Chicago | 30 | 31 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 23 | 23 |

| Female | 75 | 77 |

| Hispanic or Latino origin | ||

| Hispanic | 6 | 6 |

| Non-Hispanic | 92 | 94 |

| Race or racial heritage (check all that apply) | ||

| White | 51 | 55 |

| Black or African American | 19 | 20 |

| Asian | 23 | 25 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 | 1 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 | 1 |

| Type of clinician | ||

| Physician | 65 | 66 |

| Nurse practitioner | 20 | 20 |

| Certified nurse midwife | 6 | 6 |

| Physician's assistant | 7 | 7 |

| Primary clinical specialty | ||

| Family medicine | 35 | 36 |

| Internal medicine | 8 | 8 |

| Obstetrics/gynecology | 52 | 53 |

| Pediatrics | 1 | 1 |

| Years providing clinical care | 98 | 8.8 ± 9.5 |

| Primary care outpatient settings | ||

| 1 | 68 | 71 |

| 2 | 19 | 20 |

| ≥3 | 9 | 9 |

| Hours/week providing direct patient care | 97 | 37.5 ± 13.9 |

| Professional time spent in various activities (% per month) | ||

| Primary care, mean percent | 96 | 66.9 ± 34.4 |

| Subspecialty care, mean percent | 96 | 20.0 ± 31.9 |

| Research, mean percent | 96 | 1.3 ± 3.4 |

| Teaching, mean percent | 96 | 6.6 ± 13.5 |

| Administration, mean percent | 96 | 5.4 ± 10.9 |

| Other, mean percent | 95 | 0.8 ± 5.3 |

| Follow published guidelines for cervical cancer screening and management | ||

| Yes | 92 | 94 |

| No | 3 | 3 |

| Don't know | 3 | 3 |

| Clinic implemented guidelines for cervical cancer screening and management | ||

| Yes | 63 | 66 |

| No | 20 | 21 |

| Don't know | 13 | 13 |

| Affiliation with a medical school, adjunct clinical, or other faculty appointment | ||

| Yes | 26 | 27 |

| No | 71 | 73 |

| Last time participated in a CMEa on HPVb testing or screening | ||

| Within the past 3 years | 73 | 75 |

| 3–6 years ago | 7 | 7 |

| >6 years ago | 4 | 4 |

| Never | 13 | 14 |

CME = continuing medical education.

HPV = human papillomavirus.

HPV test and screening interval practices

For patients ≥30 years of age, 39% of providers reported usually or always using the co-test for screening, and 91% reported usually or always using the HPV test for management after an ASC-US Pap test (not reported in a table or figure).

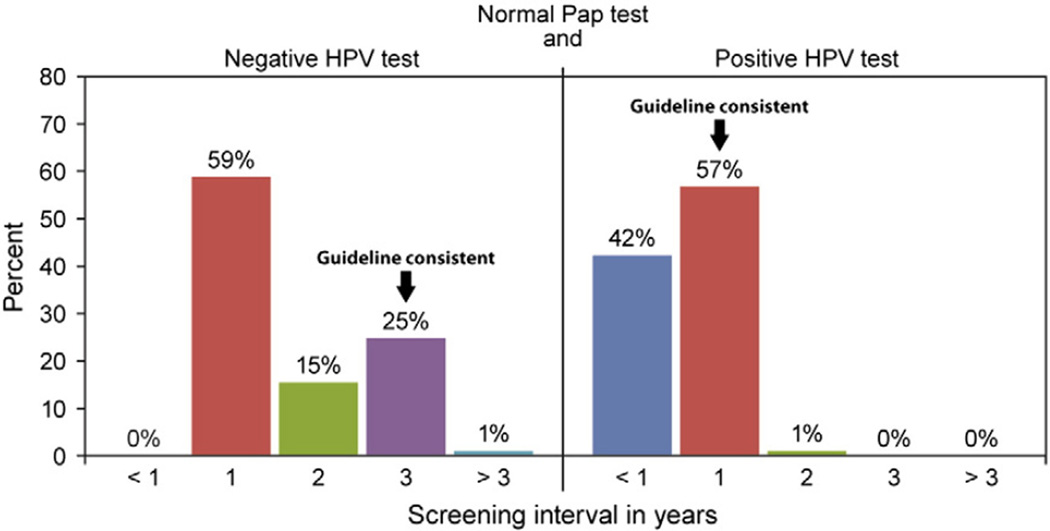

Given a clinical vignette of a 35 year old woman with a normal co-test result, over half of providers would recommend her next screening in one year (59%), only 25% would recommend next screening in three years, which was the guideline-consistent recommendation at the time of study. For the same woman with a normal Pap test and positive HPV test, 42% of providers would screen her in less than one year, and most (57%) would recommend the next screening in one year, the guideline-consistent recommendation at the time of study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Primary care provider recommended screening intervals based on the co-test result for a woman 35 years of age (n = 97), 2009–2010. (Study was conducted in 15 Federally Qualified Health Center clinics in Illinois, USA, 2009–2010). HPV = human papillomavirus.

Perceived support for using the co-test and extending the interval

Providers perceived professional journals (77%), professional specialty organizations (74%), and national health organizations (69%) to be more encouraging of co-test use in women ≥30 years of age than patients (34%), colleagues (50%), and administration in their practice (38%). Nearly one-fifth of providers (18%) perceived their administration discouraging use of the co-test (Table 3).

Table 3.

Perceived support by providers who completed the baseline survey for the Cx3 Study for use of the co-test and extending the screening interval among women ≥30 years of age, 2009–2010. (Study was conducted in 15 Federally Qualified Health Center clinics in Illinois, USA, 2009–2010).

| Use of the co-test for routine screeninga | Extending the screening interval with a normal co-test result a, b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Discourage | Neither | Encourage | N | Discourage | Neither | Encourage | |

| Patients | 97 | 2% | 64% | 34% | 97 | 27% | 59% | 14% |

| Colleagues | 96 | 5% | 45% | 50% | 97 | 22% | 47% | 31% |

| Administration in their practice | 96 | 18% | 44% | 38% | 97 | 20% | 63% | 17% |

| Professional specialty organizations | 94 | 6% | 20% | 74% | 96 | 13% | 33% | 54% |

| National health organizations | 95 | 4% | 27% | 69% | 95 | 10% | 33% | 57% |

| Professional journals | 96 | 4% | 19% | 77% | 95 | 10% | 36% | 54% |

For women ≥30 years of age.

Three-year screening interval.

More than half of providers perceived national health organizations (57%), their professional specialty organizations (54%), and professional journals (54%) to encourage extending the screening interval to three or more years with a normal co-test result in women ≥30 years of age, while their perceptions of in-clinic sources of support including colleagues (31%), administration (17%), and patients (14%) was much lower. Providers perceived that nearly one-quarter of patients, colleagues and administration in their practice would discourage extending the screening interval (Table 3).

Beliefs about co-testing and extending the screening interval

The majority of providers stated that co-testing women ≥30 years of age was extremely or quite good (85%), easy (73%), and beneficial (87%). No providers reported that co-testing was extremely or quite bad or harmful, but 10% reported co-testing was difficult (not reported in a table or figure).

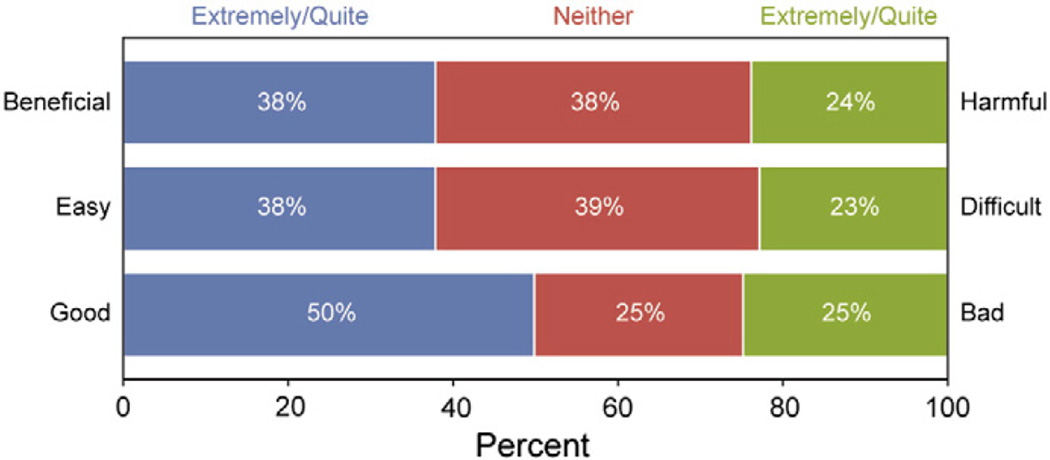

Many providers reported that extending the screening interval for a woman ≥30 years of age with a normal co-test result would be extremely or quite good (50%), with 38% stating it would be beneficial or easy. One-quarter reported beliefs that extending the screening interval with the co-test would be extremely or quite harmful (24%), difficult (23%), and bad (25%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Primary care provider beliefs about extending the screening interval to 3 years for a woman ≥30 years of age with a normal co-test result, 2009–2010. (Study was conducted in 15 Federally Qualified Health Center clinics in Illinois, USA, 2009–2010). Total n for each measure: beneficial-harmful n = 94; easy-difficult n = 95; good-bad n = 95. Survey questions: Deciding to extend the cervical cancer screening interval to 3 or more years because a woman ≥30 years of age had received a normal Pap result and negative HPV test would be… 1) good versus bad; 2) easy versus difficult; and 3) beneficial versus harmful.

Factors considered when deciding to extend the screening interval

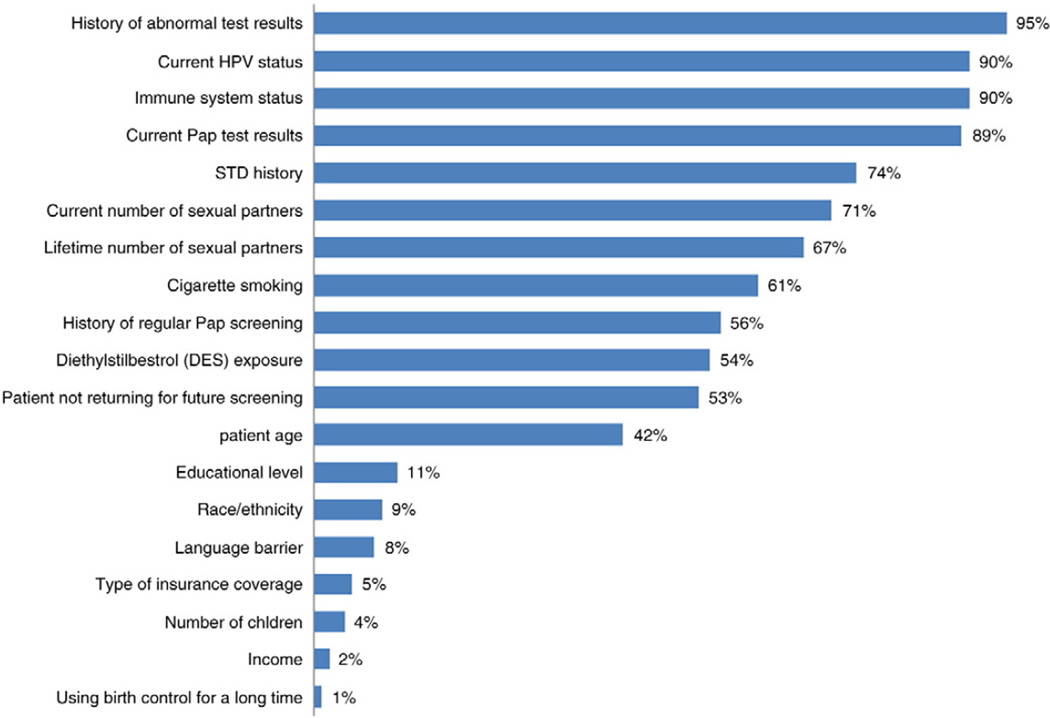

Nearly all providers considered medical history factors, such as history of abnormal test results (95%) and immune system status (90%) “a great deal” when deciding to extend the screening interval for a woman ≥30 years of age. Factors related to sexual history, such as history of a sexually transmitted infection (STI) (74%), current and lifetime number of sexual partners (71% and 67%, respectively) were considered important by over two-thirds of providers. Exposures and other behaviors, such as cigarette smoking (61%), history of regular Pap test screening (56%), and diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure (54%), and patient not returning for future screening (53%) were moderately important (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Factors considered important to primary care providers when deciding to extend the screening interval for a women ≥30 years of age1 (n = 97), 2009–2010. (Study was conducted in 15 Federally Qualified Health Center clinics in Illinois, USA, 2009–2010). 1No distinction made as to whether the Pap test or the HPV and Pap test (co-test) would be used to screen.

Perceived risks and benefits to extending the screening interval

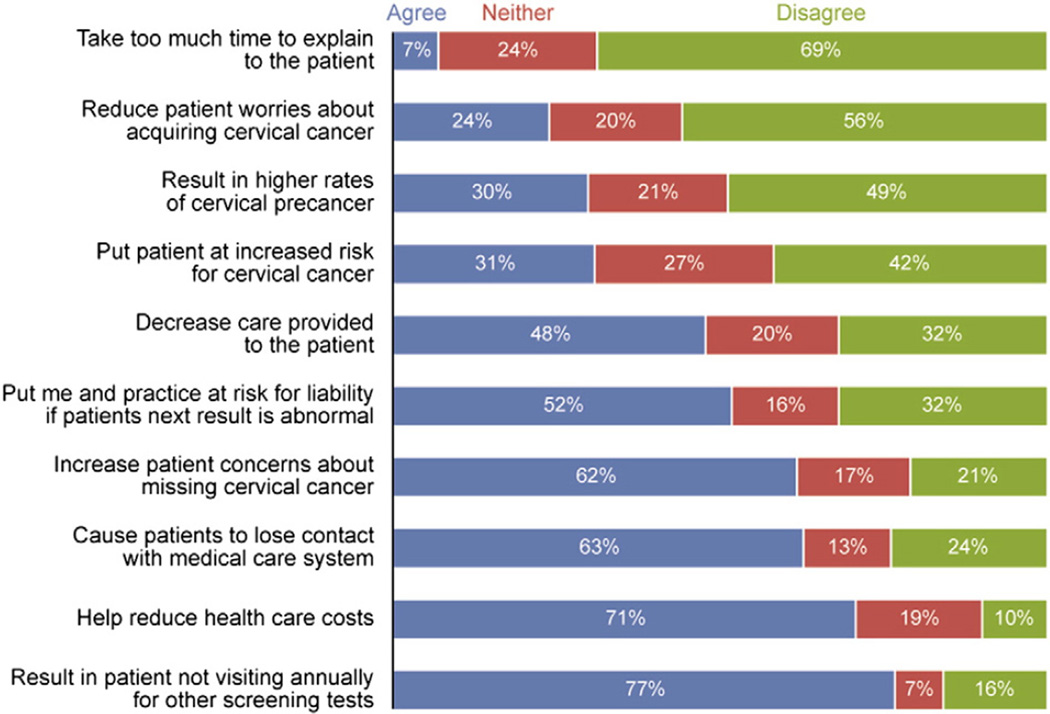

Many providers reported an extended interval for a woman ≥30 years of age with a normal co-test result would result in the patient not visiting annually for other screening tests (77%), losing contact with the medical system (63%), and having increased concerns about missing cervical cancer (62%). Providers also felt at risk for liability if the patient's next result was abnormal (52%). One benefit of extending the interval widely endorsed by providers was that it would help to reduce healthcare costs (71%) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Primary care provider perceived risks and benefits to extending the screening interval for a 30 year old woman with a normal co-test result, 2009–2010. (Study was conducted in 15 Federally Qualified Health Center clinics in Illinois, USA, 2009–2010). The total n for all measures = 97, except for “help reduce healthcare costs”, and “increase patient concerns about missing cervical cancer” where n = 96.

Discussion

Most primary care providers believe that co-testing is good and beneficial, however, in practice less than half routinely used the HPV test for screening, and the majority would recommend next screening in one year after a normal co-test result, despite 94% of providers reported following published guidelines for cervical cancer screening that recommend triennial intervals. Poor adherence to guidelines may be due to less perceived support for extending the screening intervals for a normal co-test result compared to simply using the co-test. Specifically, providers reported less support from within the clinic (patients, colleagues, and administration), compared to national-level sources (professional organizations, professional journals, and national health organizations) for both co-testing and extending screening intervals, which may signal a potential need for coupling clinic-focused with systems-level interventions.

Reported concerns about losing patients to follow-up, and personal risk of liability may hinder willingness to extend screening intervals. However, one commonly perceived benefit to extending intervals was the potential for reducing healthcare costs, a facilitator especially salient for public clinics such as FQHCs. While the perceived benefit in cost reduction is potentially helpful at a clinician- and system-level within FQHCs, patients would likely be less interested in messages about extending intervals that emphasized the reduction of costs to the clinic or public health system (Sirovich et al., 2005).

When deciding whether to extend a screening interval, factors related to a woman's medical and sexual history were most important to providers. Relevance of medical and sexual history in decision-making should diminish over time as the co-test has greater sensitivity for detection of high-grade cervical pre-cancer and cancer compared with the Pap test, the screening interval can be lengthened despite new STIs acquired in the interim, and the age of sexual initiation is no longer recommended as a reference for determining screening initiation. Immune system status, cited by 90% of providers as very important to determining intervals, is however, recognized by all professional organizations as an exception to screening guideline adherence, and should prevail as an important consideration. Conversely, in utero DES exposure, which increases risk for cervical cancer in women older than 40 years, (Smith et al., 2012) is explicitly mentioned in current guidelines as a risk factor that warrants more frequent screening, was noted by only 54% of providers.

The literature has long reported barriers to the implementation of evidence-based preventive health services and cancer screening at the patient-, provider-, clinic-, and health-system levels (Ahmad et al., 2001; Davis and Taylor-Vaisey, 1997; Jhala and Eltoum, 2007; Meissner et al., 2012; Tatsas et al., 2012; Wender, 1993). One-on-one education is effective in addressing provider cancer screening behaviors (Gorin et al., 2006; Sheinfeld et al., 2000; Yeager et al., 1996), however, interventions that address barriers and behavior change through a multi-level, social-ecological approach are most likely to improve cancer prevention and care (Clauser et al., 2012; Meissner et al., 2004; Taplin et al., 2012).

This study is unique because it surveys provider practices in addition to the beliefs, attitudes, risks, and facilitators that drive their practice, revealing more about the behavioral environment within which the provider makes their clinical decisions. However, these findings are descriptive due to the small sample size, and therefore do not convey differences in responses according to provider demographics. The literature is largely lacking as to whether providers serving low-income populations have similar uptake of preventive health guidelines and procedures. As such, we do not know how these findings compare to FQHC providers in other states, or Illinois primary care providers not working in FQHCs. However, Benard et al. found providers who serve more rural, low-income, under-insured and racially-diverse women shared low adherence to cervical cancer screening guidelines with providers serving the general population (Benard et al., 2011).

Primary care providers are crucial to the successful delivery of evidence-based cervical cancer screening. Monitoring their practices and beliefs as screening modalities and recommendations evolve is critical, especially among providers who serve low-income populations, as they may be their patient's only point of contact with the healthcare system. Additionally, understanding how providers adhere to cancer screening guidelines and general preventive health recommendations for the underserved is important to answer how limited resources can be used effectively, and whether extended screening guidelines intended for the average-risk population are appropriate for those with less frequent or sporadic access to care. As such, continued assessment of screening practices of FQHC providers across states and regions is imperative. Efforts are ongoing to increase capacity of FQHCs to provide clinical services, (Plescia et al., 2012) and as FQHCs receive funding to expand community-based, primary care services to under-insured, low-income populations, their providers have increasing responsibility for delivery of evidence-based cervical cancer screening services for women most at-risk.

Conclusion

Cervical cancer screening practices of providers serving low-income women are consistent with previous studies highlighting slow uptake of the co-test despite positive beliefs and attitudes in the utility of the co-test, and resistance to guideline-consistent screening intervals with normal co-test results (Benard et al., 2011; Holland-Barkis et al., 2006; Roland et al., 2011, 2013; Saraiya et al., 2010; Yabroff et al., 2009). Low encouragement from colleagues, patients and clinic administration for extending the screening intervals, and genuine concerns over losing patients to follow-up and being held accountable for a missed diagnosis may support these results. Continued intervention that targets appropriate use of the co-test, and the harms of too-frequent screening, and sensitizes providers to screening interval messages is necessary to balance the abundance of perceived harms to extending screening intervals.

Acknowledgment

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This manuscript was written in the course of employment by the United States Government and it is not subject to copyright in the United States. The authors gratefully acknowledge the medical directors and administrators from the Federally Qualified Health Centers who participated in the study, and the Illinois Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program.

Source of funding Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 200-2002-00573, Task Order No. 0006.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

References

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 109: cervical cytology screening. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1409–1420. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c6f8a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin number 131: screening for cervical cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;120(5):1222–1238. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e318277c92a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad F, Stewart DE, Cameron JI, Hyman I. Rural physicians' perspectives on cervical and breast cancer screening: a gender-based analysis. J. Womens Health Gend. Based Med. 2001;10(2):201–208. doi: 10.1089/152460901300039584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apgar B, Kittendorf AL, Bettcher CM, Wong J, Kaufman AJ. Update on ASCCP consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical screening tests and cervical histology. Am. Fam. Physician. 2009;80(2):147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benard VB, Johnson CJ, Thompson TD, et al. Examining the association between socioeconomic status and potential human papillomavirus-associated cancers. Cancer. 2008;113(10 Suppl.):2910–2918. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benard VB, Saraiya M, Soman A, Roland KB, Yabroff KR, Miller J. Cancer screening practices among physicians in the national breast and cervical cancer early detection program. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20(10):1479–1484. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley TG, Effros RM, Palar K, Keeler EB. Waste in the U.S. Health care system: a conceptual framework. Milbank Q. 2008;86(4):629–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch FX, Lorincz A, Munoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV. The causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 2002;55(4):244–265. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.4.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer screening — United States, 2010. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2012a;61:41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers—United States, 2004–2008. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2012b;61:258–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauser SB, Taplin SH, Foster MK, Fagen P, Kaluzny AD. Multilevel intervention research: lessons learned and pathways forward. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2012;2012(44):127–133. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzick J, Arbyn M, Sankaranarayanan R, et al. Overview of human papillomavirus-based and other novel options for cervical cancer screening in developed and developing countries. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl. 10):K29–K41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A. Translating guidelines into practice. A systematic review of theoretic concepts, practical experience and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. CMAJ. 1997;157(4):408–416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedewa SA, Cokkinides V, Virgo KS, Bandi P, Saslow D, Ward EM. Association of insurance status and age with cervical cancer stage at diagnosis: national cancer database, 2000–2007. Am. J. Public Health. 2012;102(9):1782–1790. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good Stewardship Working Group. The “top 5” lists in primary care: meeting the responsibility of professionalism. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011;171(15):1385–1390. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorin SS, Ashford AR, Lantigua R, et al. Effectiveness of academic detailing on breast cancer screening among primary care physicians in an underserved community. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2006;19(2):110–121. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.2.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habbema D, De Kok IM, Brown ML. Cervical cancer screening in the United States and the Netherlands: a tale of two countries. Milbank Q. 2012;90(1):5–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland-Barkis P, Forjuoh SN, Couchman GR, Capen C, Rascoe TG, Reis MD. Primary care physicians' awareness and adherence to cervical cancer screening guidelines in Texas. Prev. Med. 2006;42(2):140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idestrom M, Milsom I, Andersson-Ellstrom A. Women's experience of coping with a positive Pap smear: a register-based study of women with two consecutive Pap smears reported as CIN 1. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2003;82(8):756–761. doi: 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2003.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhala D, Eltoum I. Barriers to adoption of recent technology in cervical screening. CytoJournal. 2007;4:16. doi: 10.1186/1742-6413-4-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner HI, Vernon SW, Rimer BK, et al. The future of research that promotes cancer screening. Cancer. 2004;101(5 Suppl.):1251–1259. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner HI, Klabunde CN, Breen N, Zapka JM. Breast and colorectal cancer screening: U.S. primary care physicians' reports of barriers. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012;43(6):584–589. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsonego J, Cortes J, da Silva DP, Jorge AF, Klein P. Psychological impact, support and information needs for women with an abnormal Pap smear: comparative results of a questionnaire in three European countries. BMC Womens Health. 2011;11:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-11-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, et al. The causal link between human papillomavirus and invasive cervical cancer: a population-based case–control study in Colombia and Spain. Int. J. Cancer. 1992;52(5):743–749. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plescia M, Richardon LC, Joseph D. New roles for public health in cancer screening. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2012;62(4):217–219. doi: 10.3322/caac.21147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland KB, Soman A, Benard VB, Saraiya M. Human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou tests screening interval recommendations in the United States. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;205(5):447–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland KB, Benard VB, Soman A, Breen N, Kepka D, Saraiya M. Cervical cancer screening among young adult women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarker. Prev. 2013;22(4):580–588. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1266. Available from: http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/1055-9965.EPI-12-1266). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraiya M, Berkowitz Z, Yabroff KR, Wideroff L, Kobrin S, Benard V. Cervical cancer screening with both human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou testing vs Papanicolaou testing alone: what screening intervals are physicians recommending? Arch. Intern. Med. 2010;170(11):977–985. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saslow D, Runowicz CD, Solomon D, et al. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of cervical neoplasia and cancer. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2002;52(6):342–362. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.6.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. J. Low Genit. Tract Dis. 2012;16(3):175–204. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31824ca9d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheinfeld GS, Gemson D, Ashford A, et al. Cancer education among primary care physicians in an underserved community. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2000;19(1):53–58. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman ME, Lorincz AT, Scott DR, et al. Baseline cytology, human papillomavirus testing, and risk for cervical neoplasia: a 10-year cohort analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003;95(1):46–52. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirovich BE, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. Screening for cervical cancer: will women accept less? Am. J. Med. 2005;118(2):151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EK, White MC, Weir HK, Peipins LA, Thompson TD. Higher incidence of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the cervix and vagina among women born between 1947 and 1971 in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23(1):207–211. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9855-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taplin SH, Anhang PR, Edwards HM, et al. Introduction: understanding and influencing multilevel factors across the cancer care continuum. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2012;2012(44):2–10. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsas AD, Phelan DF, Gravitt PE, Boitnott JK, Clark DP. Practice patterns in cervical cancer screening and human papillomavirus testing. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2012;138(2):223–229. doi: 10.1309/AJCPPVX91HQMNYZZ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2003. [Accessed January 28, 2013]. FDA approves expanded use of HPV test. ( http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/DeviceApprovalsandClearances/Recently-ApprovedDevices/ucm082556.htm. [Google Scholar]

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Recommendation Statement: Screening for Cervical Cancer. [Accessed January 28, 2013];Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2012 http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf11/cervcancer/cervcancerrs.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Walboomers JMM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J. Pathol. 1999;189:12–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wender RC. Cancer screening and prevention in primary care. Obstacles for physicians. Cancer. 1993;72(3 Suppl.):1093–1099. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930801)72:3+<1093::aid-cncr2820721326>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabroff KR, Saraiya M, Meissner HI, et al. Specialty differences in primary care physician reports of Papanicolaou test screening practices: a national survey, 2006 to 2007. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151(9):602–611. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-9-200911030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager KK, Donehoo RS, Macera CA, Croft JB, Heath GW, Lane MJ. Health promotion practices among physicians. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1996;12(4):238–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]