Abstract

Background

Developed in Norway, Sisom is an interactive, rigorously tested, computerized, communication tool designed to help children with cancer express their perceived symptoms/problems. Children travel virtually from island to island rating their symptoms/problems. While Sisom has been found to significantly improve communication in patient consultations in Norway, usability testing is warranted with US children prior to further use in research studies.

Objective

To determine the usability of Sisom in a sample of English and Spanish speaking children in an urban US community.

Methods

A mixed methods usability study was conducted with a purposive sample of healthy children and children with cancer. Semi-structured interviews were used to assess healthy children’s symptom recognition. Children with cancer completed 8 usability tasks captured with Morae® 3.3 software. Data were downloaded, transcribed, and analyzed descriptively.

Results

Four healthy children and 8 children with cancer participated. Of the 44 symptoms assessed, healthy children recognized 15 (34%) pictorial symptoms immediately or indicated 13 (30%) pictures were good representations of the symptom. Six children with cancer completed all tasks. All children navigated successfully from one island to the next, ranking their symptom/problem severity, clicking the magnifying glass for help, or asking the researcher for assistance. All children were satisfied with the aesthetics and expressed an interest in using Sisom to communicate their symptoms.

Conclusions

A few minor suggestions for improvement and adjustment may optimize the use of Sisom for US children.

Implications for Practice

Sisom may help clinicians overcome challenges assessing children’s complex symptoms/problems in a child-friendly manner.

Significant evidence demonstrates that children with cancer experience a large number of complex psychological, physical, school-related, and behavioral symptoms and problems during and after treatment1. Yet, efforts to manage these symptoms/problems (here on end referred to as symptoms) have not kept pace with new advances in curative therapy2. Children with cancer continue to experience distressing symptoms caused by both disease and treatment1. To help communicate their distress, Ruland et al 3 developed Sisom (the acronym is derived from a play on the Norwegian phrase “Si det som det er”, or “Say it like it is”). Sisom is an interactive, computerized tool that has shown to significantly improve communication in pediatric oncology clinic consultations in Norway4. Children embark on a journey through an island world where they can express how they feel, which in turn can help parents and health care providers better understand and support the child4. Derived from an extensive literature search3 and developed with white Norwegian children, Sisom eliminates several limitations associated with previous paper instruments, such as the disregard of the child’s development stage or the use of proxy or adult-adapted versions1. Despite completed rigorous testing in Norway, important design issues relevant to other childhood cancer populations have remained unexplored3

Children from varying social, cultural, and geographical backgrounds may respond differently to the same events or representations in Sisom3. An important next step is to test the usability of Sisom with a group of healthy children and children with cancer from a different background. Using healthy children and children with cancer as Sisom informers, partners, and testers, present with certain advantages and limitations3. Healthy children can participate during the more time consuming and demanding parts of the design process permitting children with cancer to participate in less demanding design steps3. On the other hand, healthy children’s capacity to serve as proxies is limited, as they have not been confronted with a life threatening disease3; thus, it remains imperative that the children with cancer contribute to the usability testing3. Hence, the aim of this study was to test the usability of Sisom with a group of healthy children and children with cancer from an urban US community with a predominantly Dominican and Puerto Rican Spanish-speaking neighborhood. The research questions were: (1) What is the usability, in terms of pictorial and textual recognitions, from the perspective of healthy, English-speaking children? and (2) What is usability of Sisom, in terms of ease of use, usefulness, and aesthetics5, from the perspective of English and Spanish-speaking children with cancer?

Sisom

Sisom is an interactive assessment and communication tool designed to provide children with a voice. The tool utilizes spoken text, sound, animations, and intuitively meaning metaphors and pictures to express or depict symptoms that even younger children who cannot read can respond to3. Each of the 82 symptoms is represented by an animated picture. Children can indicate whether the symptom applies to them and select the level of severity on a 5-point Likert scale. There are 5 islands: (1) About Managing Things (3 sub islands; 16 symptoms); (2) My Body (5 sub islands; 28 symptoms); (3) Thoughts and Feelings (3 sub islands; 19 symptoms); (4) Things one Might be Afraid of (0 sub islands; 8 symptoms), and (5) At the Hospital (0 sub islands; 11 symptoms). After the child has visited the islands, the program displays a child-friendly symptom report. The development of Sisom is based on the Microsoft.Net, Microsoft SQL-Server, and Adobe Flash platforms. (Sisom is currently being rebuilt to run on all types of platforms including the iPad, Android, tablets and iPhone.) Sisom stores all text and sound as separate XML files that are automatically uploaded. Sisom is available as either a web-based module for online access, a stand-alone application that can be installed on different devices such as an android tablet for use at the point of care, or as an extended version for integration with other hospital information systems. The Sisom database can be used to chart the children’s symptom patterns over time and calculate statistical data. A demo of Sisom is available at http://www.communicaretools.org/sisom/sisom-children.aspx.

Methods

Design and Participants

Following institutional review board approval and informed consent and assent, a mixed methods, usability testing study3,6 was conducted. Purposive sampling techniques were utilized to recruit children, aged 6 to 12 years, over a 5-month period (January 2012 to May, 2012) from a diverse urban community. The sampling criteria consisted of: (1) English-speaking, healthy children, and (2) English- and/or Spanish-speaking children with cancer who were receiving treatment or follow-up care at the university-affiliated tertiary care pediatric hospital. This hospital has one of the largest pediatric oncology programs in the US, serving as a referral center for patients across the country and abroad.

Our aim was to recruit a ‘handful’7 of children (i.e. 4 to 5 healthy children, 4 to 5 English-speaking children with cancer, and 4 to 5 Spanish-speaking children with cancer). Our projected sample size was (a) congruent with evidence suggesting that 80% of usability problems are detected with 4 to 5 subjects7,8, and (b) consistent with prior Sisom-related research3. Using a participatory design approach, Ruland et al3 recruited a total of 33 healthy children and 12 children with cancer to participate in various Sisom-related design and testing sessions. Healthy children piloted (n = 4) or participated (n = 12) in 4 consecutive 2-hour design sessions; evaluated the graphical representations of the symptoms (n = 5); contributed to the selection of meaningful child-friendly symptom terms (n = 8); and tested the Sisom prototype (n = 4). Children with cancer participated in the later stages of the design process as end-users. Similar to the healthy children, they contributed to the selection of meaningful child-friendly symptom terms (n = 6) and tested the Sisom prototype (n = 6). Although the number of children may be perceived as ‘small’ for each of the design stages, collectively these children offered a substantial amount of feedback during the design process (e.g. they generated 161 design ideas and provided 22 hours of videotape data for the ‘adult’ design team). In anticipation we would also detect problems and generate similar feedback with a similar projected sample size and considering the ethical considerations of involving children with cancer3, the resources available for study, and the novelty of our approach, the projected sample size was justifiable.

Recruitment

The healthy children were recruited by reaching out to the local community including faculty, staff, students, and alumni to help identify potential participants. If a parent expressed an interest in hearing more about the study, his/her contact information was provided to a member of the research team who contacted the parent and arranged to meet at the School of Nursing.

The children with cancer were recruited by reaching out to the health care professionals who considered the child’s health status and interest in participating in the study during a scheduled clinic appointment. Interpreter resources available through Columbia University Medical Center were used to approach the parents of the Spanish-speaking children. To protect the families’ privacy, the health care team assisted by identifying, screening, and approaching the families to determine if they were interested in hearing more about the study. If the parent expressed an interest in hearing more about the study, their names and contact information were provided to a member of the research team who approached the parent, provided a verbal and written explanation of the study, and if agreeable, obtained written informed consent from the parent and assent from the child.

Data Collection

To determine if healthy children could correctly recognize the pictorial representation of Sisom symptoms, depicted in 2 of the 5 islands (About Managing Things and My Body), each child was presented with one, non-labeled, non-animated symptom picture at a time3. For each of the 44 pictures, children were asked to identify the depicted symptom3. If the children did not recognize the symptom, they were told the designated island label under which the symptom belonged to3. If the symptom remained unrecognizable, the children were informed of the depicted symptom and asked for recommendations to improve the depicted symptom such as drawing a new picture with the colored pencils3. Assistance was available from a member of the research team when needed. Moreover, opportunities for the children to debrief, ask questions, and offer feedback were provided. Efforts were made to ensure the child was comfortable. The interviews were conducted in one of the small conference rooms at the School of Nursing by a member of the research team with clinical and research training in pediatric nursing. Additionally, the children were instructed they could stop the interview whenever they desired. Meanwhile, parents were offered the choice to remain by their child’s side but were requested to refrain from interrupting the interview.

The usability testing for children with cancer was not much different from using the actual Sisom application3. The testing encompassed an iterative range of processes for identifying how the children with cancer actually interacted with Sisom with the goal of meeting their needs3. Using the interactive web-based module for online access with a laptop computer and mouse, the children were offered the choice to complete Sisom in English or Spanish. They also completed 8 tasks, which included the ability to (1) build an avatar, (2) select the first island, (3–7) visit each of the 5 islands, and (8) generate a symptom report. Morae® 3.3 usability software, activated at the beginning of the instruction, was used for automatic recording and analysis of all verbalizations; input device signals such as mouse clicks and movements; and Sisom screen shots such as when the child selected the avatar, rated the symptom severity, or clicked on the magnifying glass for help3. In anticipation, the children would be unable to visit all islands (e.g. due to fatigue), they were requested to visit the 2 of the 5 islands first (About Managing Things and My Body). During the testing, our observations were recorded such as documenting whether there were any problems using Sisom and inquiring whether the children enjoyed using Sisom. Following completion of their assessment, children were presented with an android tablet to determine their willingness to use Sisom with a tablet at the point of care.

The children were instructed to independently login into Sisom and visit at least two islands (About Managing Things and My Body). Assistance was available from a member of the research team when needed. Moreover, opportunities for the children to debrief, ask questions, and offer feedback were provided. Efforts were made to ensure the child was comfortable. The interviews were conducted in one of the clinic consult rooms by a member of the research team familiar to the child. Additionally, the children were instructed they could stop using Sisom whenever they desired. Meanwhile, parents were offered the choice to remain by their child’s side but were requested to refrain from interrupting the testing procedures.

Instrumentation and Interview Guides

Semi-structured interview guides outlining the procedures, questions, and probes to obtain the usability-related information from the perspectives of healthy children and children with cancer were utilized. The questions and probes were guided by methodologies used to assess the children’s understanding of the pictures and texts depicted in Sisom (for the healthy children) and their perceptions of the Sisom application (i.e. in terms of ease of use, usefulness, and aesthetics). The guides also included a package containing non-animated, Sisom colored-images and various colored pencils and paper for children to offer their insight and make any recommended changes. An abbreviated version of the Family Information Measure9 was used to collect socio-demographic information.

Data Analysis

All data were analyzed at the testing lab at the Columbia University School of Nursing10. Data derived from the picture recognition assessment were transcribed verbatim. The data coding included stratifying the children’s responses into four groups: (a) the symptom, presented as a single picture, was correctly recognized immediately (e.g. within 5 seconds) (scored as 1); (b) the symptom was recognized after knowing the island name under which it belongs (scored as 2); (c) knowing the symptom, the picture is a good representation (scored as 3); and (d) the picture does not represent the symptom well (scored as 4)6. Additionally, a list of recommendations to enhance the picture was generated. Data derived from testing Sisom were recorded with Morae® 3.3 and downloaded, coded, and analyzed descriptively11. Our observations and documentations were also recorded. The transcribed data were analyzed using content analysis techniques involving an iterative process of data reduction, data display, conclusion drawing, and verification12 with the aim of identifying any issues related to Sisom usability from the perspective of healthy children and children with cancer11. An audit trail, composed primarily of methodological and analytical documentation, was kept to permit the transferability of the process and findings to other clinical settings13.

Results

All healthy children (and their parents) approached for study assented/consented to participate; whereas 25 children with cancer were assessed for eligibility, 18 were approached, and 8 assented. Eight mothers of children with cancer consented to participate; 2 mothers consented with a Spanish-interpreter. Parents who refused consent felt their child would not be interested in the study. In two of the cases, parents consented but their child declined assent. Other than lack of interest, no other reasons were provided. No child withdrew from study. In total, 4 healthy children and 8 children with cancer participated in the study including 4 females and 8 males. The mean age of the children was 9.08 (SD 2.54, range 6–12 years). The children lived in a mean 4.5 person household (SD 1.68, range 2–8). Parents reported their children were of the following ethno-cultural backgrounds: American, Arabic, Argentinean, Dominican, El Salvador, Jewish, Incas, Italian, Irish, Japanese, Pakistani, and Spanish. Other child and family characteristics are reported in Table 1. One father along with 1 mother and 1 younger sibling were present for 2 of the healthy children interviews. All mothers of the children with cancer (n = 8) were present for the interviews along with 1 sibling.

Table 1.

Child and Family Socio-demographic Characteristics

| Characteristics | Healthy Child (n = 4) | Child with Cancer (n = 8) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age (yr) | 7.75 | 2.87 | 9.75 | 2.25 |

| Family Household Size | 3.75 | 0.96 | 4.88 | 1.89 |

|

| ||||

| No. | % | No. | % | |

|

| ||||

| Child Sex | ||||

| Male | 3 | 75 | 5 | 63 |

| Female | 1 | 25 | 3 | 38 |

| Language Spoken at Home | ||||

| English | 4 | 100 | 4 | 50 |

| Spanish | 0 | 0 | 4 | 50 |

| Bilingual Household | 2 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Parental Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 3 | 75 | 6 | 75 |

| Divorced or separated | 0 | 0 | 2 | 25 |

| Widowed | 1 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| Parental Ethnicity | ||||

| Asian | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12.5 |

| Caucasian | 2 | 50 | 1 | 12.5 |

| Hispanic | 2 | 50 | 5 | 62.5 |

| Middle Eastern | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12.5 |

| Parental Education | ||||

| Elementary school (some or completed) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12.5 |

| Some secondary/high school | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12.5 |

| Completed secondary/high school | 0 | 0 | 3 | 37.5 |

| Some post-secondary (university or college) | 1 | 25 | 1 | 12.5 |

| Received university or college degree/diploma | 1 | 25 | 2 | 25 |

| Postgraduate | 2 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Health Insurance for Child | ||||

| Medicaid | 0 | 0 | 8 | 100 |

| Private | 4 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Cancer Diagnosis | ||||

| Leukaemia | - | - | 5 | 62.5 |

| Central nervous system | - | - | 2 | 25 |

| Hepatic tumour | - | - | 1 | 12.5 |

| Time of Diagnosis | ||||

| Less than 3 months | - | - | 2 | 25 |

| 3–6 months | - | - | 1 | 12.5 |

| 6–12 months | - | - | 0 | 0 |

| 12–24 months | - | - | 2 | 25 |

| 24–36 months | - | - | 0 | 0 |

| More than 36 months | - | - | 3 | 37.5 |

| Treatment Status | ||||

| On treatment | - | - | 5 | 62.5 |

| Completed all cancer treatment | - | - | 2 | 25 |

| Relapsed | - | - | 1 | 12.5 |

| Child’s Health Status | ||||

| Excellent | - | - | 1 | 14 |

| Very Good | - | - | 3 | 43 |

| Good | - | - | 2 | 29 |

| Fair | - | - | 1 | 14 |

| Poor | - | - | 0 | 0 |

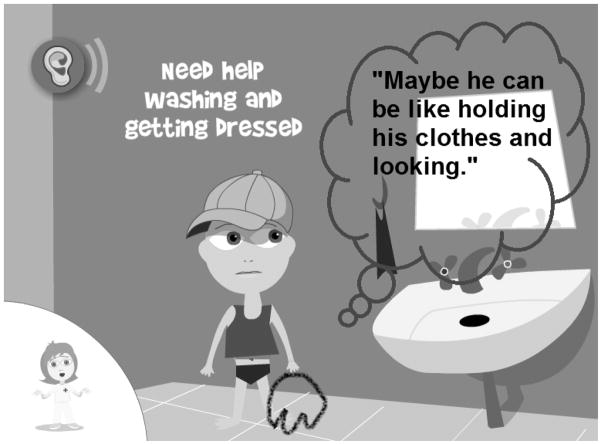

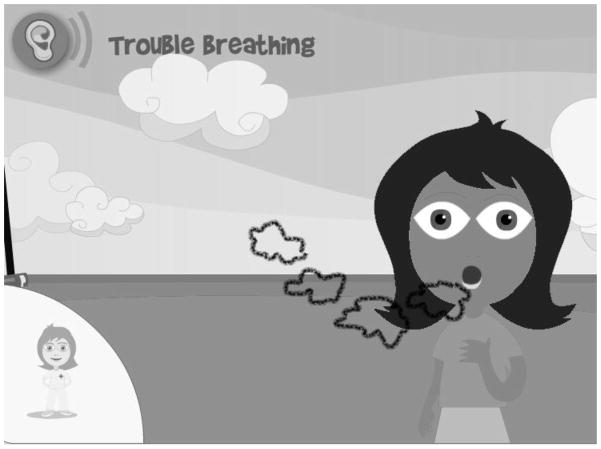

Four healthy children participated in the symptom recognition; one of which assessed only 26 of the 44 (59%) symptoms due to fatigue. Healthy children drew from their life experiences and the experiences of their siblings, friends, or other family members, to inform their symptom recognition and offer recommendation for changes. Of the 44 symptoms assessed, the healthy children recognized 15 (34%) symptoms immediately, indicated 13 (30%) pictures were good representations of the symptom, and reported 15 (34%) pictures did not represent the symptom well (Table 2). Among these unrepresented symptoms, over half of the pictures (9/15, 60%) was derived from the “About Managing Things” island, which included the “Daily Life” and “At School” sub-islands. When the healthy children indicated the symptom was not represented well, they offered solutions to improve the child’s situation as well, such as asking an adult for help when having trouble walking or running. All healthy children understood the textual meaning of 38 (86%) symptoms. Collectively, they offered 44 descriptive recommendations for 28 depicted symptoms such as covering the mouth with the arm, not the hand, when the child is coughing (Table 3) and having the child toss and turn in bed, instead of counting sheep, to depict trouble sleeping (Table 4). Moreover, the healthy children created 32 drawings to improve 23 symptoms such as inserting a clothing item to improve the washing and getting dressed problem (Figure 1); creating air clouds to demonstrate difficulty breathing (Figure 2); and suggesting the artist curl and darken the hair to depict lots of bodily hair (Figure 3). Finally, the healthy children offered 29 alternative ways of describing 15 symptoms such as “exhausted” for “tired a lot”; “can’t sleep” for “trouble sleeping”, and “water caca” for “diarrhea” (Table 5).

Table 2.

Healthy Children’s Mean Scores (n = 4) of Picture Recognition for Sisom Islands “My Body” and “About Managing Things”

| Symptom/Problem | Ratingb | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| How I look | |||

| Gotten Fatter | 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Gotten skinnier | 1 | 2.33 | 1.15 |

| Lots of hair on my body | 1 | 2.50 | 1.73 |

| Got no hair | 1 | 2.67 | 1.53 |

| How my Body Feels | |||

| Feel cold | 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Throwing up | 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Dizzy | 1 | 1.50 | 1.00 |

| Hot or sweaty | 1 | 1.50 | 1.00 |

| Tired a lot | 1 | 1.50 | 1.00 |

| Feel sick | 2 | 2.75 | 1.26 |

| Tingling in arms and legsa | 3 | 3.67 | 0.58 |

| Feeling clumsy | 3 | 3.75 | 0.50 |

| Pain and Discomfort | |||

| Rasha | 2 | 2.75 | 1.26 |

| Bruisesa | 2 | 3.00 | 1.41 |

| Pain | 3 | 3.33 | 0.58 |

| Problems I have with my body | |||

| Trouble hearing | 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Stuffy nose | 1 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Feel the heart beating fast | 1 | 2.00 | 1.73 |

| Coughing | 2 | 2.75 | 1.26 |

| Trouble breathing | 2 | 2.75 | 1.50 |

| Trouble walking or running | 2 | 2.75 | 1.26 |

| Eye Problems | 2 | 3.00 | 0.82 |

| Shaky hands | 3 | 3.50 | 0.58 |

| The Bathroom | |||

| Have to go to the bathroom all the time | 1 | 1.67 | 1.15 |

| Diarrheaa | 1 | 1.67 | 1.15 |

| Can’t hold it when I have to pee | 1 | 1.67 | 1.15 |

| Pooping hurts | 1 | 2.00 | 1.15 |

| Peeing hurts | 3 | 3.50 | 0.58 |

| Eating and Drinking | |||

| Drinking is difficult | 1 | 1.67 | 1.15 |

| Often Thirsty | 2 | 2.25 | 1.50 |

| Want to eat often | 2 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| Things taste or smell different | 2 | 3.00 | 0.00 |

| Eating is difficulta | 3 | 4.00 | 0.00 |

| Daily Life | |||

| Get tired quickly | 1 | 1.67 | 1.15 |

| Trouble sleeping | 2 | 2.50 | 1.73 |

| Need help washing and getting dressed | 3 | 3.33 | 0.58 |

| Relaxing is difficulta | 3 | 3.50 | 0.58 |

| To do things by myself is difficult | 3 | 3.75 | 0.50 |

| At School | |||

| Can’t follow when others talk | 3 | 3.33 | 0.58 |

| Concentrating is hard | 3 | 3.33 | 0.58 |

| Reading and writing is difficult | 3 | 3.33 | 0.58 |

| Don’t learn as much as the others | 3 | 3.50 | 0.58 |

| Can’t do anything for very long | 3 | 3.50 | 0.58 |

| Forget things | 3 | 4.00 | 0.00 |

Island “My Body” included 5 sub islands: “How I look”, “How My Body Feels”, “Pain and Discomfort”, “Problems I have with My Body”, and “The Bathroom”. Island “About Managing Things” included 3 sub islands: “Eating and Drinking”, “Daily Life”, and “At School”.

1 or 2 children did not understand the symptom meaning

Scores ranged from 1 to 4. A score of 1 indicates the children correctly recognized the symptom immediately whereas a score of 4 implied the children found the picture did not represent the symptom well.

A score of 1 indicates the symptom was immediately recognized; a score of 2 indicates the depicted symptom was a good representation; and a score of 3 indicates the picture does not represent the symptom well.

Table 3.

Healthy Children’s Description of Symptoms Mistaken for and Recommendations for Change for Sisom Island “My Body”

| Symptom/Problem | Mistaken for | Recommendation for Change |

|---|---|---|

| How I look | ||

| Lots of hair on my body | Itchiness; needles; spikes on body | Curl the hair; darken the hair |

| Got no hair | Blood; a child shaving his head | Try to replace hair; add exclamation mark after sentence |

| How My Body Feels | ||

| Dizzy | Confused | Extend arms out to help the child balance |

| Hot or sweaty | Tired; mad; sunburned | Add a sun in the background |

| Feel sick | Stomach hurts; sad | Place hand on tummy |

| Tingling in arms and legs | Chicken pokes; itchy; mosquito bites; 'spiked' | Remove dots on arms and legs; replace dots with 'pins and needles' |

| Feeling clumsy | Bored, sleepy | Change the scenario to a child bumping into an object while trying to catch a balloon; untie the child’s shoelaces to facilitate tripping |

| Pain and Discomfort | ||

| Rash | Scratch; a dot | Make the color lighter |

| Bruises | - | Change color to brown |

| Pain | Sore; tattoo with stars | Replace stars with unhappy faces |

| Problems I have with my body | ||

| Feel the heart beating fast | - | Add lines to illustrate movement |

| Coughing | Tired; yawning; sneezing | Cover mouth with arm not hand |

| Trouble breathing | Scared; surprised; shocked; feels sick | Demonstrate air coming in and out of the mouth; keep the hand on the chest; have an air cloud coming out of the mouth; move chest back and forth; make gasping sounds; suck in stomach; hunch over; move back and forth |

| Trouble walking or running | Problems with knees | Make the child look sad |

| Eye Problems | Tired; very tired; exhausted; sad; mad; angry | Add a little scar above eye; add eye glasses |

| Shaky hands | Cold; trying to open and close hands; trouble using their hands | Extend arms and legs; add lines to illustrate movement |

| The Bathroom | ||

| Peeing hurts | Needs to go pee so bad, hurt himself | Make the child look sad |

Island “My Body” included 5 sub islands: “How I look”, “How My Body Feels”, “Pain and Discomfort”, “Problems I have with My Body”, and “The Bathroom”.

✍ Number of drawings provided to illustrate suggestion for change recommendation

The children recommended the following 11 symptoms remain as depicted in the picture: Gotten Fatter, Gotten skinnier, Feel cold, Throwing up, Tired a lot, Trouble hearing, Stuffy nose, Have to go to the bathroom all the time, Diarrhea, Can’t hold it when I have to pee, and Pooping hurts. The children provided 1 or 2 drawings for all the symptoms with the exception of: Feel the heart beating fast and Coughing.

Table 4.

Healthy Children’s Description of Symptoms Mistaken for and Recommendations for Change for Sisom Islands “About Managing Things”

| Symptom/Problem | Mistaken for | Recommendation for Change |

|---|---|---|

| Eating and Drinking | ||

| Eating is difficult | Full | Place hand on stomach, hold tummy |

| Daily Life | ||

| Trouble sleeping | A little freaked out; sheep flying in the air; having dreams | Depict child tossing, turning and rolling around in bed |

| Need help washing and getting dressed | Trouble washing hands; wants to wash hands | Hold the clothes |

| Relaxing is difficulta | Tired; feet hurt; feel sad; feel lonely; feel scared; mom calling on him to complete homework; sleeping | Relax on the floor with books and toys |

| To do things by myself is difficult | Bored; lonely | Make the child look down and sad; close the mouth; frown the face; create smaller eyes; display a thinking face |

| At School | ||

| Can’t follow when others talk | Children are being mean to the other child; child has no friends; child does not know the answer | Place the hands over the ears; add a question mark over the child’s head |

| Concentrating is hard | Thinking about an elephant; reading and learning; imagining | Make the child look away from the book |

| Reading and writing is difficult | Having a test; drawing a picture | Add words to the text; rest head on hand |

| Don’t learn as much as the others | A little bit surprised; getting a little shy because they don’t know the answers | Make the child look sad; add tears |

| Can’t do anything for very long | Confused; a little difficult cleaning up; trying to figure it out; trying to do a puzzle | Add a clock to demonstrate how long it is taking the child to complete the task |

| Forget things | Daydreaming; spacing out | Add a question mark above the head; keep the clouds |

Island “About Managing Things” included 3 sub islands: “Eating and Drinking”, “Daily Life”, and “At School”.

1 or 2 children did not understand the symptom meaning.

The children provided 1 to 3 drawings for all the symptoms with the exception of: Trouble sleeping and Relaxing is Difficult.

The children recommended the following 5 symptoms remain as depicted in the picture: Drinking is difficult, Often Thirsty, Want to eat often, Things taste or smell different, and Get tired quickly.

Figure 1.

Healthy child suggests “holding the clothes” to improve depicted “Need help washing and getting dressed” problem (“About Managing Things” island)

Figure 2.

Healthy child suggests “show air coming in and out of the mouth” to improve depicted “Trouble Breathing” symptom (“My Body” island)

Figure 3.

Healthy child suggests “curl and darken the hair” to improve depicted “Lots of hair on my body” symptom (“My Body” island)

Table 5.

Other Ways of Describing 15 Sisom Symptoms from a Healthy Child Perspective

| Symptom | Other Ways of Describing Symptom |

|---|---|

| Tired a lot | Exhausted |

| Trouble hearing | Can’t hear too good |

| Feel the heart beating fast | Heart hurts; heart attack |

| Shaky hands | Trouble using hands |

| Stuffy nose | Has a cold; that's snot; need to blow nose; need a tissue; boogers |

| Trouble breathing | Asthma; can't breathe |

| Have to go to the bathroom all the time | Have to use the bathroom; have to pee |

| Diarrhea | Water caca; more caci; loose caci |

| Pooping hurts | Constipated; caca hurts |

| Drinking is difficult | Trouble drinking |

| Often Thirsty | Thirsty |

| Want to eat often | Have to eat again; want to eat a lot; eat too much |

| Get tired quickly | Sleepy; tired |

| Need help washing and getting dressed | Trouble washing hands; want to wash hands |

| Trouble sleeping | Can’t sleep |

All Spanish-speaking children with cancer (n = 5) were offered the choice to complete Sisom in English or Spanish using the interactive, web-based module for online access. Three Spanish-speaking children with cancer completed the English-version Sisom. Six children with cancer completed all tasks. One child with cancer did not complete 3 island-related tasks due to fatigue; whereas the other child with cancer missed the same 3 island-related tasks because s/he was called for a procedure. Both children with cancer did not visit the other 3 islands (Thoughts and Feelings, Things one Might be Afraid of, and At the Hospital). All children with cancer navigated successfully from one island to the next, ranking their symptom severity, clicking the magnifying glass for help, or asking the researcher for assistance. Children with cancer spent an average of 3.26 minutes (SD 2.6) to complete each task, for a total of 25.35 minutes (SD 7.70) (Table 6). The children with cancer spent the majority of their time ranking the severity of 28 “My Body” symptoms (Table 6). One child with cancer particularly enjoyed clicking the magnifying glass, which permitted him or her to determine which symptom he or she had not ranked the severity yet. Of the total 48 clicks, this child with cancer accounted for half of the clicks (Table 6). The majority of children with cancer (5/8) encountered at least one situation where they needed help from the researcher with the youngest participant accounting for the majority of events (9/16). Collectively, the researcher helped the children with cancer by (a) explaining the use of the Likert scale to 3 children; (b) revisiting the use of the magnifying glass with 1 child; (c) instructing them where to click; or (d) explaining that certain objects are not clickable such as window. Errors encountered included unknowingly leaving an island without completing the symptom assessment or returning to an island to reassess the same symptom (Table 6). Although all children with cancer were able to build their avatar, 5 of them attempted to dress their avatar with hair and a cap or handkerchief, which is not permitted. (Sisom permits the selection of one headpiece (i.e. hair, cap or handkerchief). All children with cancer were satisfied with the aesthetics and expressed an interest in using Sisom to communicate their symptoms. The majority of mothers did not disrupt the testing; however, 1 mother questioned her child’s ranking of selected symptoms whereas another mother indicated her child’s assessment was a good reflection of his or her current status.

Table 6.

Sisom Ease of Use Scores from the Perspective of Children with Cancer (n = 8)

| Mean Time to Complete Each Task (in Minutes) | Total Number of Events Children: | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tasks | Needed Help | Clicked on the Magnifying Glass a | Did not Complete the Island Assessment | Re- assessed the Same Symptom | Left Island and Returned to Complete Assessment | Returned to an Already Assessed Sub Island | ||

| Mean | SD | Number | Number | Number | Number | Number | Number | |

| Build Avatar | 0.58 | 0.24 | 1 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Select First Island | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Visit each of the Five Islands | ||||||||

| About Managing Things | 4.36 | 1.34 | 3 | 13 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| My Body | 8.80 | 2.21 | 6 | 48 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 2 |

| Thoughts and Feelings | 3.59 | 1.98 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Things One Might be Afraid of | 2.85 | 1.52 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| At the Hospital | 2.55 | 1.56 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Generate a Report | 3.00 | 2.74 | 0 | 0 | - | 1 | 0 | - |

| Total | 25.35 | 7.70 | 16 | 73 | 8 | 19 | 3 | 4 |

Clicking on the magnifying glass permitted the children to determine which symptom they had not ranked the severity yet. One child opted to click on the magnifying glass 24 times.

Discussion

A mixed methods approach was used to determine the usability of Sisom with a diverse group of informers and end users. The sample characteristics, which could not have been more different than the initial Norwegian sample3, consisted of multi-ethnic healthy children and children with cancer from varying socio-economic backgrounds residing and/or receiving care in an urban US community. Our findings provided preliminary insight into the usability of Sisom for a US population.

Healthy children offered minor suggestions for improving the non-animated pictures whereas children with cancer navigated successfully through each task, were satisfied with the aesthetics, and found Sisom useful to communicate their symptoms. However, a few recorded encounters suggest there may be areas for improvements and adjustments to optimize the use of Sisom for US children. Healthy children were recruited to participate in the more time consuming and demanding part of the usability testing, which consisted of testing the pictorial representation of Sisom. Over 60% of the non-animated, symptom-depicted pictures were recognized immediately or described as a good representation by the healthy children. These pictures included typically encountered childhood symptoms such as “feel cold”, “stuffy nose”, or “hot or sweaty”. A third of the pictures did not depict the symptom well. These pictures were derived primarily from the “About Managing Things” island and included the “Daily Life” and “At School” sub-island symptoms, which may be challenging to depict (even for an adult) without the additional cues of text, sound, animation, or metaphor for symptoms such as “forget things”, “relaxing is difficult”, or “concentrating is hard”.

The healthy children understood the majority of symptoms depicted and offered alternative ways of describing symptoms such as “water caca” for diarrhea. “Caca” is a term often used in the Hispanic population, even among the non-Spanish speaking Hispanics, to describe children’s bowel movements. An opportunity to enhance Sisom may include the creation of a dictionary or glossary of terms for children who do not understand the meaning, especially for the children who have not experienced the symptom. Although not all of the healthy children’s suggestions may serve useful for the developers, the children’s suggestions were insightful and serve as a reminder of the importance of incorporating children as informers, partners, and testers in usability testing.

Children with cancer tested Sisom by using the actual web-based application in a “real-world” clinical setting. Sisom was easy to use, spending an average of three minutes per task. A greater proportion of time was spent on the “My Body” island due to the number of questions compared to the other islands. Sisom captivated the children with cancer. Nearly all of them completed each island assessment. Children who were unable to complete the assessment expressed a desire to resume Sisom at a later time, which was not feasible for study purposes. Despite successfully navigating through each task, a few errors or requests for assistance were encountered, which may warrant revisiting. For example, another prompt may be required for children who unknowingly leave the island without completing their symptom assessment. Currently, each island becomes a highlighted green-color when the child completes the entire assessment. Additionally, a few children required help using the Likert scale to rank their symptoms. A different prompt may be added permitting “Mary” to provide the children with a different explanation. Finally, a few children may require additional assistance using Sisom. Not all children will be turning off the help button, as did one child in our study; thus, an additional check may be warranted for first time, and perhaps ongoing users.

Sisom may be useful in clinical practice. Clinicians are confronted with numerous challenges assessing children’s complex symptoms1,14 and may benefit from an innovative system to gather children’s experience of health and illness. In Norway, Ruland4 determined that children with cancer who use Sisom expressed a significantly greater number of symptoms than their peers during "conventional" physician consultations. Children with cancer were better prepared for their consultations improving their capacity to communicate their symptoms4. Moreover, when physicians actively use the Sisom symptom report, they ask a greater number of clarifying questions, give more detailed explanations, and communicate with greater empathy; all within the same time period allocated for “conventional” consults4. Our study demonstrated children with cancer are engaged, intrigued and prompted to discuss their symptoms. As the children with cancer navigated from one island to the next, they inquired about the symptom meanings or indicated they had not encountered this symptom, for example. Our anecdotal reports also suggest the children’s mothers, who were not recruited for study (e.g. to elicit their perceptive), expressed interest in using Sisom to enhance their children’s communication of symptoms. Finally, the children with cancer enjoyed the aesthetics of Sisom including creating their avatar, sailing from one island to the next, using the magnifying glass, ranking their symptom severity, and discussing their symptom report. Unlike the healthy children, the children with cancer suggested no changes to Sisom.

One of the study strengths included the use of a mixed method design, which provided good insight into children’s perception of the usability of Sisom. However, due to limited resources, only 2 of the 5 islands were assessed for symptom recognition (from a healthy child perspective). Moreover, our strict approach of using non-animated pictures may have precluded healthy children’s capacity to recognize immediately other symptoms such as “trouble breathing”, “eye problems”, or “trouble walking or running”. A different approach may be warranted to assess healthy children’s symptom recognition, if deemed necessary. Sisom uses text, sound, animation, and intuitively meaning metaphors to depict the symptoms, which the healthy children were not privy too. However, whether healthy children are needed for future testing of Sisom is another consideration since the children with cancer did not raise any concerns about the pictorial representations including the pictures the healthy children indicated did not depict the symptoms well. These contradictory findings also contribute to the ongoing debate as to whether healthy children can serve as proxy design participants, which remains poorly understood in the literature3. Although researchers often report great return on usability studies with groups of 5 participants7,8,15, our findings may be limited due to the number subgroups apparent in the childhood cancer population such as the different ages, cancers, developmental stages, treatment phases, or cognitive abilities. Requesting parents to refrain from disrupting the testing may not be always feasible. To what extent the mother’s disruption in our study impacted her child’s experience remains unknown. In the future, researchers may want to consider incorporating parents in the testing to lessen the potential disruption but also to elicit their perceptive (e.g. to measure proxy-reporting or determine how to use with child). Finally, only the web-based module for online access was tested. Delays in software development precluded the ability to use Morae® 3.3 or a similar software with an android tablet, which may be more convenient for point of care use (e.g. the tablet is lighter, smaller, and uses no mouse).

With Sisom, nurses have an opportunity to learn how to improve pediatric patient care, assess and manage symptoms, transfer self-management skills, and use communication technology to improve patient-provider communication and outcomes. Already Sisom has shown to significantly increase the number of symptoms reported by children16 and improve the communication of symptoms in patient consultations4. Moreover, our study findings demonstrate the usability of Sisom and confirm children’s interest in using Sisom to communicate their symptoms. While our findings may lay some of the ground work for the usability of Sisom in a “real world” US clinical setting, a multi-perspective research approach is needed to (a) understand its usability among the childhood cancer subgroups over the long-term; (b) determine how to implement Sisom, within a clinical setting with established routines, norms, and rituals17; (c) identify and measure clinically meaningful outcomes; and (d) maintain the sustainability of Sisom in practice.

In conclusion, our findings provided preliminary insight into the usability of Sisom for a US population. Healthy children offered minor suggestions for improvement whereas the recordings of the children’s interaction suggest possible areas for improvements. The proposed usability testing is the first step towards our ultimate goal of finding clinically useful and meaningful approaches to ease the children’s cancer symptoms. Opportunities to use Sisom, to help children express their symptoms, are evident. Future research should be directed towards implementing and evaluating Sisom in practice.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements, Credit, Disclaimers, and Funding Sources

We thank the children for their participation. AT was the recipient of the CUSON Dean’s Distinguished Postdoctoral Fellowship Award, sponsored by Dr. Patricia W. Stone, Director of the Center for Health Policy. An earlier draft of this manuscript was presented at the 44th Congress of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) 2012, London United Kingdom. The SIOP abstract was published in Pediatric Blood and Cancer, 59 (6), 2012. The study was supported by a research grant from the Sigma Theta Tau International Alpha Zeta Chapter. The study also used infrastructure resources provided by the Center for Evidence-based Practice in the Underserved (P30NR0010677).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Ruland C, Hamilton G, Schjødt-Osmo B. The complexity of symptoms and problems experienced in children with cancer: a review of the literature. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2009;37(3):403–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hockenberry M. Symptom management research in children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2004;21(3):132–136. doi: 10.1177/1043454204264387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruland CM, Starren J, Vatne TM. Participatory design with children in the development of a support system for patient-centered care in pediatric oncology. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2008;41(4):624–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruland C. Interactive, child-friendly communication support can help children with cancer communicate their illness experiences and improve consultations. 44th Congress of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) 2012; October 5–8, 2012; London, United Kingdom. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thuring M, Mahike S. Usability, aesthetics and emotions in human-technology interaction. Int J Psychol. 2007;42(4):253–264. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vatne TM, Slaugther L, Ruland CM. How children with cancer communicate and think about symptoms. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2010 Jan-Feb;27(1):24–32. doi: 10.1177/1043454209349358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nielsen J. Usability engineering at a discount. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the third international conference on human-computer interaction on Designing and using human-computer interfaces and knowledge based systems; 1989; Boston, Massachusetts, United States. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Virzi RA. Refining the test phase of usability evaluation: How many subjects is enough? Human Factors. 1992;34(4):457–468. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsimicalis A, Stevens B, Ungar WJ, et al. A Prospective Study to Determine the Costs Incurred by Families of Children Newly Diagnosed with Cancer in Ontario. Psycho-Oncology. doi: 10.1002/pon.2009. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Columbia University School of Nursing. [Accessed May 30, 2012];CEBP Core Resources. 2011 http://www.cumc.columbia.edu/dept/nursing/research/EBPcoreRes.html.

- 11.Zhang J, Patel V, Johnson K, Smith J, Malin J. Designing human-centered distributed information systems. IEEE Intelligent Systems. 2002;17(5):42–47. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miles MB, Huberman AM. An expanded sourcebook: Qualitative data analysis. 2. Thounsand Oaks: SAGE Publisher; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodgers BL, Cowles KV. The qualitative research audit trail: a complex collection of documentation. Research in Nursing & Health. 1993 Jun;16(3):219–226. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770160309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsimicalis A, De Courcy MJ, Di Monte B, et al. Tele-practice guidelines for the symptom management of children undergoing cancer treatment. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2011;57(4):541–548. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karwowski W, Turner CW, Lewis JR, Nielsen J, editors. International Encyclopedia of ergonomics and human factors. 2. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 2006. Determining usability test sample size. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baggott C, Ruland C, Hinds P, Miaskowski C. Sisom: A computerized assessment tool to enahce the collection of patient-reported outcomes from children. 44th Congress of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) 2012; October 5–8, 2012; London, United Kingdom. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruland CM, Bakken S. Developing, implementing, and evaluating decision support systems for shared decision making in patient care: a conceptual model and case illustration. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2003;35(5/6):313–321. doi: 10.1016/s1532-0464(03)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]