Abstract

Background

Current U.S. guidelines recommend consideration of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) for pregnant smokers if behavioral therapies fail, only under close supervision of a provider, and after discussion of known risks of continued smoking and possible risks of NRT. The percentage of pregnant smokers offered NRT by their prenatal care providers is unknown.

Purpose

The study aims to calculate the percentage of pregnant smokers offered cessation intervention and NRT and assess independent associations between selected maternal characteristics and being offered NRT.

Methods

Data were analyzed from the 2009–2010 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System from four states that asked about provider practices for prenatal smoking cessation. Adjusted prevalence ratios were calculated to examine associations between being offered NRT, selected maternal characteristics, and smoking level. Variables used in adjusted models were based on factors associated with smoking cessation during pregnancy from prior literature and included race, age, education, insurance type, and stress.

Results

Of 3559 women who smoked 3 months before pregnancy, 77.4% (95% CI: 74.2, 80.3) of 3rd trimester smokers and 42% (95% CI: 38.5, 46.4) of women who quit smoking during pregnancy were offered at least one cessation method. Among smokers, 19.1% (95% CI: 16.5, 22.1) were offered NRT and of these, almost all (94%) were offered another cessation method.

Conclusions

One in five pregnant smokers was offered NRT. About a quarter of pregnant smokers did not receive any interventions to stop smoking. There may still be reluctance to provide NRT to pregnant women, despite known harms of continued smoking during pregnancy.

Keywords: Nicotine replacement therapy, Smoking, Prenatal care counseling, Smoking cessation, Tobacco use cessation products, Maternal smoking

Introduction

Tobacco use during pregnancy is the most prevalent cause of poor infant outcomes for which effective interventions exist (US Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] 2014). Prenatal smoking causes adverse outcomes including placental abruption, preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (USDHHS 2014). The last decade has seen modest declines in prevalence of prenatal smoking; however, data from the 2010 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) show that 23% of women with live births smoked cigarettes before pregnancy and 11% of women smoked in the 3rd trimester of pregnancy (Tong et al., 2013). These numbers fall short of targets set by the Healthy People 2020 initiative to reduce to 14.6% the percentage of women entering pregnancy smoking and reduce to 1.4% the percentage of women smoking prenatally ((USDHHS), 2013).

The 2008 U.S. Public Health Services Guidelines recommend that clinicians ask all pregnant women about tobacco use and that pregnant smokers be offered augmented pregnancy-tailored counseling (Fiore et al. 2008). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG] (2010) recommends that providers assess smoking status of their pregnant patients and deliver a brief counseling session, such as the 5A’s (ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange), to patients who are willing to quit smoking, and refer them to a smoking cessation quit line if additional support is needed. In meta-analysis, counseling interventions have been shown to improve smoking cessation during pregnancy compared to usual care (Chamberlain et al. 2013). Because safety and efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) during pregnancy have not been established, ACOG (2010) states that NRT only be used under the close supervision of a provider after all known risks of continued smoking and possible risks of NRT have been discussed, and only after behavioral therapy fails to achieve cessation in patients with a “clear resolve to quit smoking”. Bupropion and varenicline are U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications for smoking cessation in general populations; however, no trials have assessed their safety and use for cessation during pregnancy. Given that both drugs carry federally mandated product warnings about the risk of psychiatric symptoms and suicide associated with their use, ACOG (2010) recommends that pregnant patients who choose to use these medications be closely supervised.

Several studies have summarized providers’ self-reported practices of delivering smoking cessation interventions (Hartmann et al. 2007, Oncken et al. 2000, Jordan, Dake & Price 2006, Association of American Medical Colleges 2012), but fewer studies exist on pregnant women’s report of being offered interventions by their provider, including NRT. In a trial using telephone counseling, researchers found that 29% of pregnant smokers reported discussing a cessation medication, including NRT, with their obstetric providers, and 10% reported using a medication during pregnancy (Rigotti et al. 2008). Using data from a representative sample of women with a live birth in New Jersey during 2004 to 2005, another study found that almost all women reported being asked by their provider if they smoked, 57% reported their provider had spent time with them discussing how to quit, 12% reported using some type of cessation method (such as self-help materials, counseling, medications, classes, or quit lines), and 4% reported using medications (Tong et al. 2008). However, that study did not assess whether the provider had offered cessation medications such as NRT, bupropion, or varenicline to women, nor did it ask if the women were referred to a smoking cessation quit line.

Also, disparities in providing smoking cessation have been documented for the general population of smokers. Non-Hispanic Black smokers are less likely to utilize evidence-based cessation treatments (CDC 2011). Though scant, there has been mixed evidence regarding disparities in the receipt of smoking cessation interventions in prenatal care among pregnant smokers. Some studies have noted that Black pregnant women were more likely to receive provider counseling on interventions for smoking cessation (Petitti et al. 1991, Tran et al. 2010) while another noted that Black women were less likely to receive provider advice about smoking cessation (Kogan et al., 1994). Thus, exploring associations between provider assistance and maternal characteristics among pregnant smokers may help to information cessation efforts.

The objectives of this study were to determine the types of smoking cessation methods being offered by prenatal care providers in a population-based sample of pregnant smokers and to examine associations between maternal characteristics and providers’ recommendation of NRT.

Methods

Study population and data source

PRAMS is a population-based surveillance system which collects data on selected maternal behaviors and experiences before, during, and after pregnancy among women with a recent live delivery. In 2013, PRAMS included data for 41 sites: 40 states and New York City. This study analyzed 2009–2010 data from the four states (Illinois, Missouri, Oregon, and West Virginia) that collected information on prenatal care provider assistance for smoking cessation and achieved a weighted annual response rate of at least 65%. Responses are weighted to account for non-response, non-coverage and oversampling, to be representative of each state’s entire population of women delivering a live infant. Detailed methodology is described elsewhere (Shulman, Gilbert & Lansky, 2006). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Institutional Review Board approved the PRAMS protocol; all sites approved the study plan.

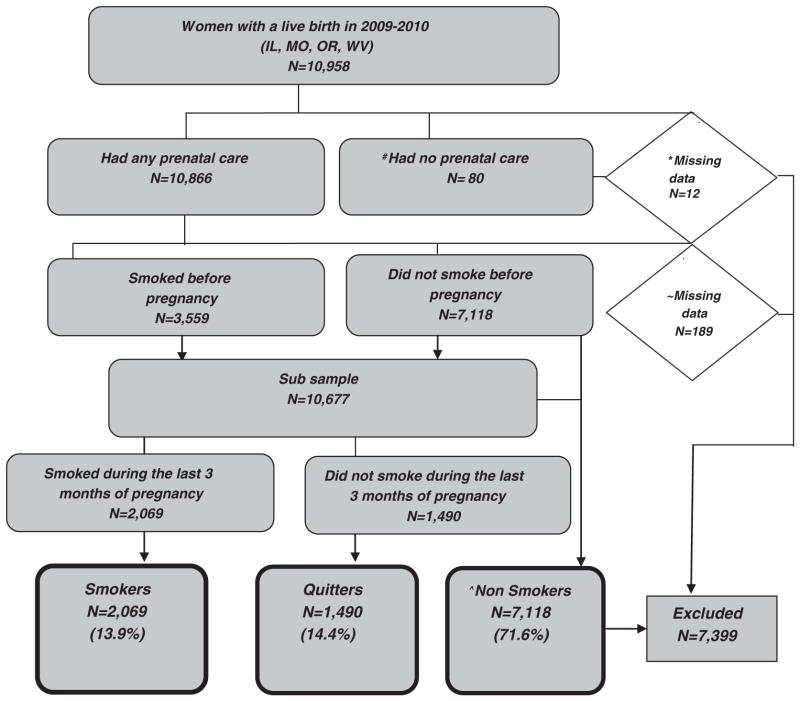

In the four states during 2009–2010, a total of 10,958 women participated in the survey. Women who had no prenatal care (n = 80) were excluded, as it was assumed providers would not have had an opportunity to offer them smoking cessation services (Fig. 1). Women with missing information on entry into prenatal care (n = 12), smoking status before and during pregnancy (n = 189), and those who were nonsmokers (n = 7118) were also excluded. The final sample included 2069 (13.9%) pregnant women who reported smoking in the last 3 months of pregnancy. Women who quit smoking by the last trimester (n = 1490) were analyzed separately from women who smoked in the last 3 months of pregnancy to examine differences in receipt of provider assistance with smoking cessation between the two groups.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of case selection criteria for this study. Exclusions: #Women who had no prenatal care on birth certificate and PRAMS survey. *Women with missing data on prenatal care on birth certificate or PRAMS survey. ~Women with missing data on smoking before or during pregnancy. ^Women who reported no cigarette use at any time 2 years before pregnancy.

Measures

Smoking status was defined using three questions from the PRAMS survey. First, all respondents were asked if they had smoked any cigarettes in the past 2 years. Women who responded ‘Yes’ were asked to specify how many cigarettes they smoked per day on average in the three months before pregnancy, and in the last 3 months of pregnancy. The response categories for both time periods included: no cigarettes, less than 1, 1 to 5, 6 to 10, 11 to 20 and 41 or more cigarettes. Smokers were categorized as women who reported smoking any cigarettes in the 3 months before pregnancy and reported smoking any (includes <1 cigarette/day) cigarettes during the last 3 months of pregnancy. Quitters were defined as women who reported smoking in the 3 months before pregnancy and did not smoke any cigarettes in the last 3 months of pregnancy. As the study is descriptive, the use of cessation interventions should be interpreted with caution. Some quitters may have quit upon learning of pregnancy and/or prior to prenatal care.

Respondents who reported smoking in the 3 months before pregnancy were asked about smoking cessation methods or services offered during prenatal care by their provider (Table 2). Cessation methods were further grouped into any cessation method (a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, or k), provider counseling (a, b, c, or f); self-help materials only (d), referral to counseling or quit line (e or g), and recommended or prescribed any NRT (h, i, or j). Timing of offer of any cessation method is not reported in PRAMS.

Table 2.

Self-reported receipt of provider assistance for smoking cessation among women who smoked 3 months before pregnancy in four states, PRAMS, 2009–2010.a

| Type of provider assistanceb | Receipt of provider assistance

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Smokersc % (95% CI) N = 2069 |

N | Quittersd % (95% CI) N = 1490 |

p-Value* | |

| a. Spend time with you discussing how to quit smoking | 1201 | 59.2 (55.7, 62.6) | 407 | 31.9 (28.3, 35.7) | <0.001 |

| b. Suggest that you set a specific date to stop smoking | 670 | 33.8 (30.5, 37.2) | 248 | 20.3 (17.3, 23.7) | <0.001 |

| c. Suggest you attend a class or program to stop smoking | 506 | 22.4 (19.7, 25.5) | 129 | 9.6 (7.8, 12.1) | <0.001 |

| d. Provide you with booklets, videos, or other materials to help you quit smoking on your own | 1018 | 48.2 (44.6, 51.7) | 306 | 23.0 (19.9, 26.5) | <0.001 |

| e. Refer you to counseling for help with quitting | 228 | 11.0 (8.9, 13.5) | 65 | 5.1 (3.7, 7.0) | <0.001 |

| f. Ask if a family member or friend would support your decision to quit | 629 | 31.8 (28.6, 35.2) | 236 | 18.1 (15.2, 21.3) | <0.001 |

| g. Refer you to a national or state quit line | 432 | 17.4 (14.9, 20.2) | 101 | 6.3 (4.7, 8.3) | <0.001 |

| h. Recommend using nicotine gum | 329 | 15.5 (13.1, 18.2) | 77 | 5.9 (4.3, 8.0) | <0.001 |

| i. Recommend using a nicotine patch | 356 | 15.0 (12.7, 17.5) | 75 | 6.1 (4.4, 8.4 | <0.001 |

| j. Prescribe a nicotine nasal spray or nicotine inhaler | 72 | 2.0 (1.3, 2.9) | 23 | 1.8 (1.0, 3.1) | NS |

| k. Prescribe a pill like Zyban® (also known as Wellbutrin® or Bupropion) or Chantix® (also known as Varenicline) to help you quit | 132 | 5.9 (4.5, 7.8) | 33 | 2.2 (1.3, 3.6) | 0.0002 |

| Categories of cessation assistance | |||||

| Any type of assistance (a through k) | 1520 | 77.4 (74.2, 80.3) | 531 | 42.4 (38.5, 46.4) | <0.001 |

| Provider counseling (a, b, c, f) | 1370 | 67.3 (63.8, 70.6) | 482 | 37.6 (33.87, 41.6) | <0.001 |

| Self-help materials only (d) | 1018 | 48.2 (44.6, 51.7) | 306 | 23.0 (19.9, 26.5) | <0.001 |

| Referral to counseling or quitline (e, g) | 504 | 22.4 (19.5, 25.5) | 124 | 8.2 (6.4, 10.5) | <0.001 |

| Provider counseling, self-help materials, or referral to quit line only (a, b, c, d, e, f, g)** | 1505 | 75.4 (72.2, 78.4) | 526 | 41.6 (37.8, 45.6) | <0.001 |

| Recommend or prescribe any nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) (h,i,j) | 432 | 19.1 (16.5, 22.1) | 91 | 7.1 (5.3, 9.5) | <0.001 |

N: unweighted sample size; CI: confidence interval.

3559 women who reported smoking 3 months before pregnancy and who had any prenatal care. Data are aggregated from four PRAMS states during 2009–2010 (Illinois, Missouri, Oregon, and West Virginia).

Type of provider assistance (a–k) was not mutually exclusive. Women could select more than one option.

Smokers: Women who reported smoking in the last 3 months of pregnancy.

Quitters: Women who reported smoking 3 months before pregnancy and no smoking in the last 3 months of pregnancy.

p < 0.05 for χ2 test of independence.

Women with non-missing items for all categories.

Maternal demographics derived from the birth certificate data included maternal race/ethnicity, age, parity, education, state of residence, and infant year of delivery. Insurance coverage during prenatal care, enrollment in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women Infants and Children (WIC) (United States Department of Agriculture [USDA] 2013), and maternal stress were derived from the PRAMS survey. Timing of entry into prenatal care was based on birth certificate data, or if missing on the birth certificate, was taken from the PRAMS survey. Maternal stress, which has known associations with smoking and decreased likelihood of cessation (Hauge, Torgersen & Vollrath 2012), was based on responses to a list of 13 negative life events included in PRAMS, such as, ‘I had a lot of bills I couldn’t pay, and ‘I lost my job even though I wanted to go on working, and was categorized into no, 1 to 2, or 3 or more stressors.

Analytic approach

PRAMS data used in this analysis were weighted to adjust for survey design and non-response, and estimates are representative of women with live births in each participating state. SUDAAN (version 11) was used for analyses to account for the complex survey design.

Prevalence estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of receipt of any or specific types of prenatal care provider assistance with smoking cessation and offer of NRT for smoking cessation were calculated overall and by demographic characteristics. Chi-square tests (p < 0.05) were used to test for differences in percentages by maternal characteristics. Multivariable analyses were performed to examine demographic and service use variables associated with receipt of provider assistance for smoking cessation and offer of NRT. Adjustments in the analyses were made for race, age, parity, marital status, education, insurance type, WIC status, smoking intensity, and maternal stress. Covariates were included in the multivariable models based on factors associated with smoking cessation during pregnancy from prior literature. (Tong et al. 2008; Vaz et al. 2014; Tran et al. 2010; Adams et al. 2008; Kogan et al. 1994; Adams et al. 1992). Infant year of birth was included in the models to control for differences over time. As PRAMS is a cross-sectional survey, unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% CIs were calculated using logistic regression, as described by Bieler and colleagues (2010).

Results

Overall, 13.9% of women reported smoking in the last 3 months of pregnancy, and 14.4% had quit by the 3rd trimester of pregnancy. Smokers tended to be age 20–29 (66.4%), non-Hispanic white (83.6%), unmarried (66.7%), have high school education or less (43.4% and 29.7%), enrolled in WIC (72.8%), insured by Medicaid (83.1%), reported 3 or more stressors (59.2%), smoke >20 cigarettes before pregnancy (13.6%) and lived in West Virginia (17.8%). Quitters had similar characteristics compared to smokers, with the exception of being primiparous (53.8%), and lighter smokers (<1–5 cigarettes per day) in the 3 month before pregnancy (52.4%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Maternal characteristics of pregnant women by smoking status in four states, PRAMS, 2009–2010 (unweighted N = 10,677).a

| Maternal characteristics | Nonsmokersb %, unweighted n = 7118 (95% CI) |

Smoked 3 months before pregnancy

|

p-Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smokersc %, unweighted n = 2069 (95% CI) |

Quittersd %, unweighted n = 1490 (95% CI) |

|||

| All women | 71.6 (70.4, 72.8) | 13.9 (13.1, 14.9) | 14.4 (13.5, 15.4) | |

| Maternal age (years) | ||||

| <20 | 9.1 (8.2, 10.1) | 12.5 (10.3, 15.0) | 14.1 (11.8, 16.9) | <0.001 |

| 20–29 | 48.5 (46.8, 50.1) | 66.4 (63.0, 69.7) | 62.8 (59.2, 66.3) | |

| ≥30 | 42.4 (40.8, 44.1) | 21.1 (18.3, 24.1) | 23.0 (20.1, 26.3) | |

| Maternal race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 62.9 (61.3, 64.4) | 83.6 (80.6, 86.2) | 78.3 (74.9, 81.2) | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11.8 (10.6, 13.1) | 9.5 (7.4, 12.2) | 9.7 (7.5, 12.5) | |

| Other | 25.3 (24.0, 26.7) | 6.9 (5.4, 8.8) | 12.0 (9.9, 14.5) | |

| Parity | ||||

| First | 41.2 (39.6, 42.8) | 35.2 (31.9, 38.6) | 53.8 (50.2, 57.4) | <0.001 |

| Second or later birth | 58.8 (57.2, 60.4) | 64.8 (61.4, 68.0) | 46.2 (42.6, 49.8) | |

| Maternal education | ||||

| <High school | 16.2 (15.0, 17.4) | 29.7 (26.6, 32.9) | 19.7 (16.9, 22.8) | <0.001 |

| High school | 22.4 (21.1, 23.9) | 43.4 (40.0, 46.9) | 31.6 (28.3, 35.1) | |

| >High school | 61.4 (59.8, 63.0) | 26.9 (23.9, 30.1) | 48.7 (45.0, 52.3) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 68.9 (67.3, 70.4) | 33.3 (30.2, 36.6) | 44.6 (41.1, 48.2) | <0.001 |

| Unmarried | 31.0 (29.5, 32.7) | 66.7 (63.4, 69.8) | 55.4 (51.8, 58.9) | |

| Trimester entry into prenatal care | ||||

| 1st | 87.2 (86.0, 88.2) | 77.9 (74.9, 80.7) | 81.9 (78.8, 84.6) | <0.001 |

| 2nd | 11.1 (10.1, 12.2) | 19.5 (16.9, 22.5) | 15.5 (13.0, 18.4) | |

| 3rd | 1.7 (1.3, 2.2) | 2.5 (1.6, 4.0) | 2.6 (1.6, 4.3) | |

| Insurance coverage | ||||

| Medicaid or public | 45.9 (44.3, 47.7) | 83.1 (80.2, 85.7) | 64.2 (60.5, 67.7) | <0.001 |

| Private/HMOe | 54.0 (52.3, 55.7) | 16.8 (14.3, 19.8) | 35.8 (32.3, 39.5) | |

| WIC programf enrollee during pregnancy | ||||

| Yes | 41.9 (40.3, 43.6) | 72.8 (69.5, 75.9) | 57.7 (54.0, 61.2) | |

| No | 58.0 (56.4, 59.6) | 27.2 (24.1, 30.5) | 42.3 (38.7, 46.0) | <0.001 |

| Maternal stressg | ||||

| 0 | 33.5 (32.0, 35.1) | 9.3 (7.6, 11.3) | 18.1 (15.4, 21.1) | |

| 1–2 | 43.6 (41.9, 45.2) | 31.5 (28.3, 34.8) | 37.0 (33.5, 40.6) | <0.001 |

| 3 or more | 22.9 (21.5, 24.4) | 59.2 (55.7, 62.6) | 44.9 (41.3, 48.6) | |

| Average number of cigarettes smoked per day in the 3 months before pregnancy | ||||

| <1–5 | NA | 13.6 (11.2, 16.3) | 52.4 (48.7, 56.0) | |

| 6–10 | NA | 29.9 (26.8, 33.2) | 24.8 (21.8, 27.9) | <0.001 |

| 11–20 | NA | 42.9 (39.5, 46.4) | 18.8 (16.1, 21.8) | |

| >20 | NA | 13.6 (11.5, 16.1) | 4.1 (2.8, 5.8) | |

| Average number of cigarettes smoked per day during last 3 months of pregnancy | ||||

| <1–5 | NA | 51.6 (48.1, 55.0) | NA | |

| 6–10 | NA | 29.5 (26.4, 32.7) | NA | |

| 11–20 | NA | 15.5 (13.2, 18.2) | NA | |

| >20 | NA | 3.4 (2.4, 4.7) | NA | |

| State | ||||

| IL | 41.6 (40.7, 42.5) | 24.3 (21.1, 27.8) | 30.8 (27.4, 34.4) | |

| MO | 30.8 (30.0, 31.6) | 41.9 (38.7, 45.2) | 38.7 (35.5, 42.0) | <0.001 |

| OR | 21.0 (20.4, 21.7) | 15.9 (13.8, 18.4) | 21.7 (19.3, 24.4) | |

| WV | 6.5 (6.3, 6.8) | 17.8 (16.4, 19.4) | 8.8 (7.8, 9.9) | |

| Infant year of birth | ||||

| 2009 | 71.3 (70.6, 72.0) | 64.2 (61.3, 67.1) | 64.8 (61.7, 67.7) | <0.001 |

| 2010 | 28.7 (28.0, 29.4) | 35.8 (32.9, 38.7) | 35.2 (32.3, 38.3) | |

NA = not applicable.

N = Unweighted sample size. Data aggregated from four PRAMS states during 2009–2010 (Illinois, Missouri, Oregon, and West Virginia); CI = confidence interval.

Nonsmokers: Women who reported no smoking at any time in the 2 years before pregnancy.

Smokers: Women who reported smoking in the last 3 months of pregnancy.

Quitters: Women who reported smoking 3 months before pregnancy and no smoking in the last 3 months of pregnancy.

HMO: Health Management Organization.

WIC: Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Maternal Stress: Number of reported negative life events.

p < 0.05 for χ2 test of independence.

Overall, 77.4% of smokers and 42.4% of quitters reported that a prenatal care provider offered at least one cessation method to help them quit (Table 2). Prevalence of receipt of almost all cessation methods was statistically higher for smokers than quitters, with the exception of receipt of nicotine nasal spray or nicotine inhaler. The method most frequently offered was provider counseling on how to quit for both smokers (59.2%) and quitters (31.9%). About one in four smokers (22.6%) and over half of quitters (57.6%) did not report receiving any smoking cessation method.

The overall prevalence of recommendation of any NRT method was almost three times greater among smokers (19.1%) than quitters (7.1%). Nicotine patch and gum were the most prevalent NRT formulations recommended compared to spray or inhaler. Of smokers offered NRT (n = 432), almost all (93.8%) reported also being offered other behavioral methods (data not shown).

Among smokers, prevalence of receipt of provider assistance was highest among women who were 20 to 29 years old, were primiparous, were enrolled in Medicaid, and who participated in WIC (Table 3). In adjusted analyses, WIC status (aPR = 1.16, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.32) and 3rd trimester entry into prenatal care (aPR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.36) remained significantly associated with receipt of provider assistance. Among quitters, receipt of provider assistance was highest among women less than age 20, with a high school education or less, unmarried, and enrolled in Medicaid and WIC. After adjusting for covariates, age <20 (aPR = 1.44, 95% CI: 1.01, 2.04), and smoking 6–10, 11–20 and >20 cigarettes per day before pregnancy (aPR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.73; aPR = 1.68, 95% CI: 1.33, 2.12 and aPR = 1.60, 95% CI: 1.05, 2.45 respectively) remained significantly associated with provider assistance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Receipt of provider assistance for smoking cessation by maternal characteristics of women who smoked 3 months before pregnancy in four states, PRAMS, 2009–2010.a

| Maternal characteristics | Smokersb N = 2069 |

Quittersc N = 1490 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receipt of provider assistance % (95% CI) | Adjusted prevalence ratiod (95% CI) | Receipt of provider assistance % (95% CI) | Adjusted prevalence ratioe (95% CI) | |

| Maternal age*,# (years) | ||||

| <20 | 79.6 (69.7, 86.8) | 1.04 (0.88, 1.24) | 61.0 (50.6, 70.5) | 1.44 (1.01 2.04) |

| 20–29 | 80.2 (76.7, 83.4) | 1.08 (0.97, 1.20) | 41.7 (36.9, 46.7) | 0.99 (0.75, 1.31) |

| ≥30 | 69.4 (61.4, 76.3) | Ref | 32.5 (24.8, 41.2) | Ref |

| Maternal race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 77.1 (73.6, 80.2) | Ref | 41.3 (37.0, 45.7) | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 84.0 (72.8, 91.1) | 1.09 (0.97, 1.22) | 51.5 (36.9, 65.8) | 1.09 (0.75, 1.58) |

| Other | 79.4 (66.5, 88.2) | 0.97 (0.81, 1.15) | 43.3 (32.6, 54.6) | 0.90 (0.66, 1.23) |

| Parity* | ||||

| First | 81.8 (76.8, 85.9) | 1.08 (0.99, 1.17) | 42.0 (36.7, 47.5) | 0.88 (0.72, 1.07) |

| Second or later birth | 75.8/ (71.8, 79.4) | Ref | 43.5 (37.8, 49.3) | Ref |

| Maternal education# | ||||

| <High school | 78.6 (72.9, 83.4) | 0.98 (0.88, 1.10) | 55.5 (46.5, 64.1) | 1.24 (0.93, 1.65) |

| High school | 79.5 (74.6, 83.6) | 1.00 (0.91, 1.10) | 46.8 (39.9, 53.7) | 1.10 (0.86, 1.42) |

| >High school | 74.9 (68.5, 80.4) | Ref | 33.5 (28.3, 39.3) | Ref |

| Marital status# | ||||

| Married | 74.4 (68.4, 79.4) | Ref | 34.4 (29.2, 39.9) | Ref |

| Other | 79.6 (75.8, 82.9) | 0.98 (0.90, 1.07) | 49.5 (44.0, 55.1) | 1.12 (0.90, 1.41) |

| Trimester entry into prenatal care | ||||

| 1st | 77.4 (73.9, 80.6) | Ref | 41.4 (37.2, 45.8) | Ref |

| 2nd | 78.6 (71.4, 84.5) | 1.02 (0.93, 1.13) | 49.8 (39.3, 60.3) | 1.01 (0.77, 1.32) |

| 3rd | 86.9 (69.3, 95.1) | 1.20 (1.06, 1.36) | 43.6 (20.2, 70.2) | 0.82 (0.38, 1.78) |

| Insurance coverage*# | ||||

| Medicaid or public | 80.3 (77.1, 83.2) | 1.07 (0.92, 1.25) | 48.7 (43.6, 53.8) | 1.07 (0.79, 1.45) |

| Private/HMOf | 67.3 (57.9, 75.5) | Ref | 31.5 (25.5, 38.2) | Ref |

| WIC programg enrollee during pregnancy*# | ||||

| Yes | 81.2 (77.9, 84.1) | 1.16 (1.03, 1.32) | 49.7 (44.5, 54.8) | 1.21 (0.92, 1.60) |

| No | 68.6 (61.3, 75.0) | Ref | 32.5 (26.8, 38.7) | Ref |

| Maternal stressh | ||||

| 0 | 75.8 (66.1, 83.4) | Ref | 33.1 (24.6, 42.8) | Ref |

| 1–2 | 77.9 (72.2, 82.8) | 1.02 (0.91, 1.15) | 43.8 (37.5, 50.3) | 1.17 (0.86, 1.58) |

| 3 or more | 77.8 (73.5, 81.6) | 0.98 (0.87, 1.10) | 44.5 (38.6, 50.6) | 1.04 (0.76, 1.43) |

| Average number of cigarettes smoked per day in the 3 months before pregnancy | ||||

| <1–5 | 77.9 (68.0, 84.5) | Ref | 33.8 (28.4, 39.6) | Ref |

| 6–10 | 76.4 (70.3, 81.5) | 1.01 (0.89, 1.15) | 49.0 (41.6, 56.5) | 1.37 (1.08, 1.73) |

| 11–20 | 77.7 (72.9, 81.9) | 1.02 (0.89, 1.16) | 52.2 (43.6, 60.7) | 1.68 (1.33, 2.12) |

| >20 | 81.9 (73.7, 87.9) | 1.09 (0.94, 1.28) | 54.7 (35.8, 72.4) | 1.60 (1.05, 2.45) |

| Average number of cigarettes smoked per day during last 3 months of pregnancy | ||||

| <1–5 | 77.0 (72.4, 81.0) | Ref | NA | NA |

| 6–10 | 81.3 (75.5, 86.0) | 1.06 (0.96, 1.16) | NA | NA |

| 11–20 | 76.8 (69.2, 83.0) | 1.06 (0.96, 1.17) | NA | NA |

| >20 | 65.1 (46.0, 80.3) | 0.99 (0.82, 1.19) | NA | NA |

| State | ||||

| Illinois | 79.0 (70.4, 85.4) | 1.07 (0.95, 1.19) | 38.6 (30.3, 47.7) | Ref |

| Missouri | 76.5 (71.4, 80.9) | Ref | 45.6 (39.6, 51.7) | 1.22 (0.91, 1.64) |

| Oregon | 81.4 (73.6, 87.2) | 1.07 (0.96, 1.19) | 43.2 (35.8, 50.9) | 1.20 (0.88, 1.64) |

| West Virginia | 76.4 (72.8, 79.8) | 0.97 (0.90, 1.05) | 41.0 (34.8, 47.6) | 1.01 (0.74, 1.39) |

| Infant year of birth* | ||||

| 2009 | 78.2 (74.0, 81.9) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.08) | 43.1 (37.9, 48.5) | 1.15 (0.93, 1.41) |

| 2010 | 77.3 (72.7, 81.3) | Ref | 42.0 (36.5, 47.6) | Ref |

CI: confidence interval.

3559 women who reported smoked 3 months before pregnancy and who received any prenatal care. Data aggregated from four PRAMS states during 2009–2010 (Illinois, Missouri, Oregon, and West Virginia).

Smokers: Women who reported smoking in the last 3 months of pregnancy.

Quitters: Women who reported smoking 3 months before pregnancy and no smoking in the last 3 months of pregnancy.

From a sample of 2069 smokers, a total of 1813 women were included in this model after exclusion of women with missing information for any covariates.

From a sample of 1490 quitters, a total of 1112 women were included in this model after exclusion of women with missing information for any covariates.

HMO: health management organization.

WIC: Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Maternal stress: number of reported negative life events.

Significant at p < 0.05 using chi-square test to compare characteristics of smokers who received provider assistance with smoking cessation and those who did not receive assistance.

Significant at p < 0.05 using chi-square test to compare characteristics of quitters who received provider assistance with smoking cessation and those who did not receive assistance.

Prevalence of receipt of a recommendation or prescription for NRT for smoking cessation, was highest among pregnant smokers with a high school education or less, entered prenatal care in 2nd trimester, who smoked 20+ cigarettes before or during pregnancy, and who lived in Oregon (Table 4). In the adjusted analysis, the strongest predictor for receipt of NRT among smokers was smoking >20 cigarettes per day during pregnancy (aPR = 2.57, 95% CI: 1.49, 4.43). Other predictors were: having a high school education (aPR = 1.77, 95% CI: 1.15, 2.71) or less (aPR = 1.64, 95% CI: 1.03, 2.63), smoking 6–10 or 11–20 cigarettes per day during pregnancy (aPR = 1.68, 95% CI: 1.15, 2.45 and aPR = 2.20, 95% CI: 1.38, 3.50 respectively) and living in the state of Oregon (aPR = 1.89, 95% CI: 1.08, 3.30). Lastly, pregnant smokers who entered prenatal care in the 3rd trimester of pregnancy (aPR = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.07, 0.59) were less likely to be offered NRT compared with pregnant smokers who entered prenatal care earlier in pregnancy. Among quitters, in adjusted analysis, non-Hispanic Black women (aPR = 3.07, 95% CI: 1.45, 6.52) and women who smoked 11–20 cigarettes per day (aPR = 3.51, 95% CI: 1.60, 7.71) were more likely to receive an offer of NRT compared to their counterparts.

Table 4.

Self-reported receipt of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) for smoking cessation by maternal characteristics of women who smoked 3 months before pregnancy in four states, PRAMS, 2009–2010.a

| Maternal characteristics | Smokersb

|

Quittersc

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offered NRT % (95% CI) | Adjusted prevalence ratiod (95% CI) | Offered NRT % (95% CI) | Adjusted prevalence ratioe (95% CI) | |

| Maternal age (years) | ||||

| <20 | 23.7 (15.8, 34.1) | 1.20 (0.67, 2.14) | 8.5 (4.3, 16.2) | 1.90 (0.65, 5.53) |

| 20–29 | 18.6 (15.5, 22.1) | 0.92 (0.63, 1.35) | 7.0 (4.9, 10.0) | 0.94 (0.39, 2.26) |

| ≥30 | 21.1 (15.6, 27.8) | Ref | 6.3 (2.9, 13.3) | Ref |

| Maternal race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 19.0 (16.2, 22.2) | Ref | 6.1 (4.4, 8.6) | Ref |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 24.2 (14.8, 37.0) | 1.54 (0.97, 2.43) | 16.7 (8.1, 31.1) | 3.07 (1.45, 6.52) |

| Other | 13.2 (7.8, 22.1) | 0.78 (0.47, 1.31) | 5.7 (2.3, 13.0) | 1.36 (0.51, 3.63) |

| Parity | ||||

| First birth | 20.0 (15.6, 25.3) | 1.16 (0.81, 1.66) | 7.0 (4.5, 10.6) | Ref |

| Second or later birth | 18.4 (15.4, 21.9 | Ref | 7.3 (4.9, 10.7) | 1.27 (0.72, 2.26) |

| Maternal education* | ||||

| <High school | 22.9 (17.9, 28.8) | 1.64 (1.03, 2.63) | 9.5 (5.5, 15.8) | 1.99 (0.92, 4.31) |

| High school | 21.7 (17.6, 26.5) | 1.77 (1.15, 2.71) | 5.2 (3.1, 8.7) | Ref |

| >High school | 11.7 (8.2, 16.5) | Ref | 7.6 (4.2, 10.3) | 1.62 (0.78, 3.39) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 18.8 (14.8, 23.6) | Ref | 6.8 (4.4, 10.5) | Ref |

| Other | 19.3 (16.1, 23.1) | 0.82 (0.61, 1.12) | 7.3 (4.9, 10.8) | 0.63 (0.29, 1.39) |

| Trimester entry into prenatal care* | ||||

| 1st | 18.5 (15.7, 21.7) | Ref | 7.1 (5.2, 9.7) | Ref |

| 2nd | 22.9 (16.7, 30.7) | 1.12 (0.81, 1.56) | 7.6 (3.2, 17.0) | 0.74 (0.35, 1.54) |

| 3rd | 6.9 (2.6, 17.0) | 0.20 (0.07, 0.59) | 4.4 (1.2, 16.2) | 0.52 (0.12, 2.20) |

| Insurance coverage | ||||

| Medicaid or public | 20.5 (17.5, 23.8) | 1.25 (0.74, 2.10) | 8.0 (5.6, 11.4) | 1.03 (0.50, 2.10) |

| Private/HMOf | 13.8 (8.8, 21.1) | Ref | 5.4 (3.0, 9.5) | Ref |

| Enrolled in WIC programg during pregnancy | ||||

| Yes | 19.4 (16.4, 22.7) | 0.85 (0.60, 1.20) | 7.8 (5.4, 11.2) | 1.25 (0.67, 2.36) |

| No | 18.5 (13.5, 24.8) | Ref | 6.0 (3.6, 9.7) | Ref |

| Maternal stressh | ||||

| 0 | 20.4 (13.1, 30.4) | Ref | 5.9 (2.7, 12.3) | Ref |

| 1–2 | 18.0 (13.9, 23.0) | 0.87 (0.53, 1.43) | 6.0 (3.5, 10.1) | 1.08 (0.43, 2.71) |

| 3 or more | 19.8 (16.2, 23.9) | 0.92 (0.56, 1.51) | 8.5 (5.6, 12.6) | 1.24 (0.53, 2.89) |

| Average number of cigarettes smoked per day 3 months before pregnancy* | ||||

| <1–5 | 16.9 (10.4, 26.4) | Ref | 4.9 (2.7, 8.6) | Ref |

| 6–10 | 18.0 (13.8, 23.2) | 1.01 (0.63, 1.62) | 5.9 (3.4, 9.9) | 1.48 (0.66 3.29) |

| 11–20 | 17.1 (13.4, 21.4) | 0.78 (0.45, 1.33) | 11.9 (7.3, 18.7) | 3.51 (1.60, 7.71) |

| >20 | 30.5 (22.6, 39.7) | 1.35 (0.74, 2.46) | 15.0 (5.7, 34.0) | 1.96 (0.58, 6.62) |

| Average number of cigarettes smoked per day during last 3 months of pregnancy* | ||||

| <1–5 | 14.6 (11.4, 18.4) | Ref | NA | NA |

| 6–10 | 21.8 (17.0, 27.4) | 1.68 (1.15, 2.45) | NA | NA |

| 11–20 | 26.0 (18.8, 34.8) | 2.20 (1.38, 3.50) | NA | NA |

| >20 | 34.1 (20.5, 50.9) | 2.57 (1.49, 4.43) | NA | NA |

| State* | ||||

| Illinois | 11.8 (7.0, 19.2) | Ref | 5.2 (2.2, 11.8) | Ref |

| Missouri | 20.6 (16.5, 25.4) | 1.27 (0.73, 2.22) | 9.3 (6.3, 13.5) | 2.24 (0.78, 6.48) |

| Oregon | 25.3 (18.5, 33.6) | 1.89 (1.08, 3.30) | 5.1 (2.6, 9.6) | 1.28 (0.35, 4.63) |

| West Virginia | 20.4 (17.4, 23.9) | 1.07 (0.63, 1.83) | 8.5 (5.5, 13.0) | 1.81 (0.53, 6.19) |

| Infant year of birth* | ||||

| 2009 | 16.8 (13.7, 20.5) | Ref | 6.2 (4.1, 9.5) | Ref |

| 2010 | 23.3 (19.1, 28.1) | 1.26 (0.94, 1.68) | 8.5 (5.8, 12.6) | 1.09 (0.59, 2.00) |

CI: confidence interval.

3559 women who reported smoking 3 months before pregnancy and who received any prenatal care. Data are aggregated from four PRAMS states during 2009–2010 (Illinois, Missouri, Oregon, and West Virginia).

Smokers: Women who reported smoking in the last 3 months of pregnancy.

Quitters: Women who reported smoking 3 months before pregnancy and no smoking in the last 3 months of pregnancy.

HMO: health management organization.

From a sample of 2069 smokers, a total of 1810 women were included in this model after exclusion of women with missing information for any covariates.

From a sample of 1490 quitters, a total of 1114 women were included in this model after exclusion of women with missing information for any covariates.

WIC: Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Maternal stress: number of reported negative life events.

Significant at p <0.05 using chi-square testing to compare characteristics of women who were offered NRT for cessation and those who were not.

Discussion

One in five pregnant women who smoked in last 3 months of pregnancy reported that their prenatal care provider recommended or prescribed NRT. Almost all women who were recommended NRT also reported receiving behavioral methods to assist with smoking cessation, which suggests that providers who prescribe NRT are doing so in accord with current ACOG (2005) clinical practice recommendations. Smoking a greater number of cigarettes per day was the strongest predictor of NRT recommendation. Also, women who lived in Oregon were more likely to report NRT recommendation.

Obstetricians and other prenatal care providers may be reluctant to prescribe NRT for prenatal smoking cessation because of the unknown risk–benefit ratio of NRT use to the woman and fetus during pregnancy compared with continued smoking during pregnancy. A meta-analysis of clinical trials of NRT for prenatal smoking cessation showed that NRT had no significant effect on quit rates (Coleman et al. 2012); however, low adherence to therapy makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions on its efficacy (Oncken 2012). Although no statistically significant differences in rates of adverse birth outcomes (e.g., stillbirth, birthweight, low birthweight) were observed between NRT or control groups (Coleman et al. 2012). However, given that nicotine is a neuroteratogen (State of California EPA 1986), neurological outcomes have not been assessed in NRT trials. More studies are needed to determine the safety, efficacy and effectiveness of NRT for smoking cessation during pregnancy. Use of electronic cigarettes, which may or may not have nicotine and flavorings, is becoming more prevalent among US adults and youth, and consumers have reported using them as cessation aids (King et al., 2013; Pokhrel et al. 2013). However, the safety, efficacy and effectiveness of these products have not been established, nor are they currently regulated by the FDA as cessation medication (USFDA, 2014). Prenatal care providers should follow current recommendations regarding effective smoking cessation aids for pregnant smokers and utilize only those that have been FDA-approved as cessation medications, if applicable.

Of smokers who were offered, recommended or prescribed an intervention (77.4%), two-thirds reported that their provider had a discussion with them about quitting smoking, and half reported receiving self-help materials. The prevalence of provider counseling (67.3%) is higher than results from previous studies (Tong et al. 2008; Chapin & Root 2004). We also found a lack of association for many of the demographic characteristics explored (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, education, insurance status), with receipt of any provider assistance which suggests that no apparent disparities were observed in provider assistance for smoking cessation. This is contrasted to the general population of smokers (CDC 2011).

Still, in our study, almost one-fourth of women who smoked in the last 3 months of pregnancy did not report any intervention by their doctor. Because our data are based on self-report, it is possible that survey respondents may not recall provider intervention. Despite this, providers may face a number of barriers that affect their ability to provide smoking cessation counseling, such as a lack of awareness of guidelines, lack of self-efficacy, lack of training, lack of systems to support counseling activities, lack of materials, and perceptions that counseling takes a long time (Chapin & Root, 2004). In addition, providers facing pregnant patients with nicotine addiction may perceive such patients as having no desire or interest in quitting (Hartmann et al. 2007) or as having major life stressors that are alleviated by smoking (Grimley et al. 2001), which could also create barriers to initiating conversations about cessation. Provider education and training on best practice approaches can help ensure all smokers who want to quit are provided effective cessation treatment (Tong et al. 2012). In addition, we found that evidence-based interventions, such as self-help booklets and quitlines, were under-utilized and could be promoted. Last, out-of-pocket costs may be another barrier that, if reduced, might improve access to smoking cessation treatment (Community Guide, 2013). The Affordable Care Act requires states to provide effective tobacco cessation counseling and medications without cost-sharing for pregnant women enrolled in Medicaid (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid 2013). As of 2012, Medicaid programs in all 50 states plus the District of Columbia cover all pharmacotherapy and some form of behavioral intervention, like quit lines or face-to-face-counseling for pregnant women (McMenamin et al., 2012). Future research will be needed to assess whether this policy will encourage changes in provider recommendation and pregnant women’s uptake of evidence-based cessation interventions.

A small but significant association was found between participating in the WIC program and receipt of smoking cessation methods may be explained at least in part by its strongly recommended programmatic and prevention strategies to assist low-income pregnant, postpartum women, and their infants, including the provision of screening and referrals to other health and social services (US Department of Agriculture [USDA] 2013). For example, in Missouri, WIC participants are provided with anti-smoking and cessation information along with other client intake materials (Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services 2013). In Oregon, all prenatal WIC applicants are screened for current smoking status at the time of their initial enrollment. Referrals are routinely made to the state quit line and local smoking cessation programs, quit line posters are displayed in clinics, and written materials on smoking cessation are available to participants (S. Greathouse, Oregon WIC Program, personal communication, April 15, 2013). These results highlight the critical importance of an integrated effort among service providers for a continuum of care during pregnancy to encourage quitting, and in the postpartum period to prevent relapse.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this study is its large population-based sample of pregnant women and their reports of providers’ practices in providing effective smoking cessation interventions, particularly recommendation of NRT. Among the limitations, the self-reported survey responses, including information about smoking cessation advice and services received during prenatal care, were collected approximately 4 months after delivery as part of a cross-sectional survey and could be subject to recall bias. Second, many women will quit smoking when learning of their pregnancy (Tong et al. 2008); thus, they would not need provider cessation assistance. Although we present estimates of provider assistance among quitters by the last trimester of pregnancy, it was not possible to discern whether women were still smoking at the time of prenatal care. So it is likely we have overestimated the population in need of smoking cessation among quitters. Lastly, the study findings are not generalizable to pregnant women beyond the study states.

Conclusion

Approximately one in four pregnant women who smoked in the last 3 months of pregnancy reported their prenatal care provider did not provide an intervention for smoking cessation. Among those who did receive or were offered an intervention, provider counseling and provision of self-help materials were the most prevalent services. One in five pregnant smokers reported being offered NRT for smoking cessation. Further research is needed to understand better how physicians are making decisions regarding NRT and which cessation methods are most effective in helping pregnant smokers quit. Efforts are also needed to ensure providers follow best practice approaches so that all pregnant smokers are offered smoking cessation interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Patricia Dietz, DrPH, MPH, for her contribution toward development of the manuscript, and the members of the PRAMS working group: Alabama—Qun Zheng, MS; Alaska—Kathy Perham-Hester, MS, MPH; Arkansas—Mary McGehee, PhD; Colorado—Alyson Shupe, PhD; Connecticut—Jennifer Morin, MPH; Delaware—George Yocher, MS; Florida—Kelsi E. Williams MPH; Georgia—Chinelo Ogbuanu, MD, MPH, PhD; Hawaii—Jane Awakuni; Illinois—Patricia Kloppenburg, MT(ASCP), MPH; Iowa—Sarah Mauch, MPH; Louisiana—Amy Zapata, MPH; Maine—Tom Patenaude, MPH; Maryland—Diana Cheng, MD; Massachusetts -Emily Lu, MPH; Michigan—Patricia McKane; Minnesota—Judy Punyko, PhD, MPH; Mississippi—Brenda Hughes, MPPA; Missouri—Venkata Garikapaty, MSc, MS, PhD, MPH; Montana—JoAnn Dotson; Nebraska—Brenda Coufal; New Hampshire—David J. Laflamme, PhD, MPH; New Jersey—Ingrid M. Morton, MS; New Mexico—Eirian Coronado, MA; New York State—Anne Radigan-Garcia; New York City—Candace Mulready-Ward, MPH; North Carolina—Kathleen Jones-Vessey, MS; North Dakota—Sandra Anseth; Ohio—Connie Geidenberger PhD; Oklahoma—Alicia Lincoln, MSW, MSPH; Oregon—Kenneth Rosenberg, MD, MPH; Pennsylvania—Tony Norwood; Rhode Island—Sam Viner-Brown, PhD; South Carolina—Mike Smith, MSPH; Texas—Tanya Guthrie, PhD; Tennessee—Ramona Lainhart, PhD; Utah—Laurie Baksh, MPH; Vermont—Peggy Brozicevic; Virginia—Christopher Hill, MPH, CPH; Washington—Linda Lohdefinck; West Virginia—Melissa Baker, MA; Wisconsin—Katherine Kvale, PhD; Wyoming—Amy Spieker, MPH; CDC PRAMS Team, Applied Sciences Branch, Division of Reproductive Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statements

Martha Kapaya has no financial disclosures.

Van Tong has no financial disclosures.

Helen Ding has no financial disclosures.

CDC Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Adams MM, Brogan DJ, Kendrick JS, Shulman HB, Zahniser SC, Bruce FC. Smoking, pregnancy, and source of prenatal care: results from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System Working Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1992 Nov;80 (5):738–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams KE, Melvin CL, Raskind-Hood CL. Sociodemographic, insurance, and risk profiles of maternal smokers post the 1990s: how can we reach them? Nicotine Tob Res. 2008 Jul;10 (7):1121–1129. doi: 10.1080/14622200802123278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians Gynecologist (ACOG) Committee opinion no. 316: smoking cessation during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:883–888. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200510000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians Gynecologist (ACOG) Committee opinion no 471: smoking cessation during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Nov;116 (5):1241–1244. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182004fcd. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182004fcd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of American Medical Colleges. [Accessed September 2012];Physician behavior and practice patterns related to smoking cessation. https://www.aamc.org/download/55438/data/smokingcessationsummary.pdf.

- Bieler GS, Brown GG, Williams RL, Brogan DJ. Estimating model-adjusted risks, risk differences, and risk ratios from complex survey data. Am J Epidemiol. 2010 Mar 1;171 (5):618–623. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Quitting smoking among adults–United States, 2001–2010. MMWR. 2011 Nov 11;60 (44):1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare, Medicaid Services, US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed September 2013];New Medicaid Tobacco Cessation Services, SDL # 11-007. 2013 2011. http://downloads.cms.gov/cmsgov/archived-downloads/SMDL/downloads/smd11-007.pdf.

- Chamberlain C, O’Mara-Eves A, Oliver S, Caird JR, Perlen SM, Eades SJ, Thomas J. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Oct 23;10:CD001055. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001055.pub4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001055.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin J, Root W. Improving obstetrician-gynecologist implementation of smoking cessation guidelines for pregnant women: an interim report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004 Apr;6 (Suppl. 2):S253–S257. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman T, Chamberlain C, Davey MA, Cooper SE, Leonardi-Bee J. Pharmacological interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Sep;12:9. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Community Guide. Guide to community preventive services. [Accessed September 2013];Reducing tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure: reducing out-of-pocket costs for evidence-based tobacco cessation treatments. www.thecommunityguide.org/tobacco/outofpocketcosts.html.

- Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: 2008. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. [Google Scholar]

- Grimley DM, Bellis JM, Raczynski JM, Henning K. Smoking cessation counseling practices: a survey of Alabama obstetrician-gynecologists. South Med J. 2001 Mar;94 (3):297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann KE, Wechter ME, Payne P, Salisbury K, Jackson RD, Melvin CL. Best practice smoking cessation intervention and resource needs of prenatal care providers. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:765–770. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000280572.18234.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauge LJ, Torgersen L, Vollrath M. Associations between maternal stress and smoking: findings from a population-based prospective cohort study. Addiction. 2012 Jun;107 (6):1168–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan TR, Dake JR, Price JH. Best practices for smoking cessation in pregnancy: do obstetrician/gynecologists use them in practice? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006 May;15 (4):400–441. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BA, Alam S, Promoff G, Arrazola R, Dube SR. Sep. Awareness and ever-use of electronic cigarettes among U.S. adults, 2010–2011. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15 (9):1623–1627. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan MD, Kotelchuck M, Alexander GR, Johnson WE. Racial disparities in reported prenatal care advice from health care providers. Am J Public Health. 1994 Jan;84 (1):82–88. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMenamin SB, Halpin HA, Ganiats TG. Medicaid coverage of tobacco-dependence treatment for pregnant women: impact of the Affordable Care Act. Am J Prev Med. 2012 Oct;43 (4):e27–e29. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missouri Department of Health, Services, Senior. [Accessed September 2013];WIC Program Publications. 2013 http://health.mo.gov/living/families/wic/wiclwp/pdf/R_0510_WIC_TobaccoCard3.pdf.

- Oncken C. Nicotine replacement for smoking cessation during pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2012 Mar 1;366 (9):846–847. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1200136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncken CA, Pbert L, Ockene JK, Zapka J, Stoddard A. Nicotine replacement prescription practices of obstetric and pediatric clinicians. Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Aug;96 (2):261–265. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00905-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitti DB, Hiatt RA, Chin V, Croughan-Minihane M. An outcome evaluation of the content and quality of prenatal care. Birth. 1991 Mar;18 (1):21–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1991.tb00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P, Fagan P, Little MA, Kawamoto CT, Herzog TA. Smokers who try e-cigarettes to quit smoking: findings from a multiethnic study in Hawaii. Am J Public Health. 2013 Sep;103 (9):e57–e62. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti NA, Park ER, Chang Y, Regan S. Smoking cessation medication use among pregnant and postpartum smokers. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Feb;111 (2 Pt 1):348–355. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000297305.54455.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman HB, Gilbert BC, Lansky A. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): current methods and evaluation of 2001 response rates. Public Health Rep. 2006 Jan-Feb;121 (1):74–83. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State of California Environmental Protection Agency. Chemicals Known to the State to Cause Cancer or Reproductive Toxicity, Proposition 65 List of Chemicals. 1986. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcemment Act of 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tong VT, England LJ, Dietz PM, Asare LA. Smoking patterns and use of cessation interventions during pregnancy. Am J Prev Med. 2008 Oct;35 (4):327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong VT, Dietz PM, England LJ. Smoking cessation for pregnancy and beyond: a virtual clinic, an innovative web-based training for healthcare professionals. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012 Oct;21 (10):1014–1017. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3871. (Epub 2012 Aug 30) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong VT, Dietz PM, Morrow B, D’Angelo DV, Farr SL, Rockhill KM, England LJ. Nov 8. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy – Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), United States, 40 Sites, 2000–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62 (SS06):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran ST, Rosenberg KD, Carlson NE. Racial/ethnic disparities in the receipt of smoking cessation interventions during prenatal care. Matern Child Health J. 2010 Nov;14 (6):901–909. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Food and Nutrition Service, WIC Program Mission. [Accessed March 2013]; http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/aboutwic/wicataglance.htm.

- US Department of and Health Human Services (USDHHS) The Health Consequences of Smoking: 50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2014. US Dept Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC: 2013. [Accessed August 2013]. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Available at www.healthypeople.gov/2020. [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) [Accessed February 2014];E-cigarettes: Questions and Answers. http://www.fda.gov/forconsumers/consumerupdates/ucm225210.htm.

- Vaz LR, Leonardi-Bee J, Aveyard P, Cooper S, Grainge M, Coleman T. Factors associated with smoking cessation in early and late pregnancy in the smoking, nicotine, and pregnancy trial: a trial of nicotine replacement therapy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014 Apr;16 (4):381–389. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]