Abstract

Translation of aberrant or problematic mRNAs can cause ribosome stalling which leads to the production of truncated or defective proteins. Therefore, cells evolved cotranslational quality control mechanisms that eliminate these transcripts and target arrested nascent polypeptides for proteasomal degradation. Here we show that Not4, which is part of the multifunctional Ccr4–Not complex in yeast, associates with polysomes and contributes to the negative regulation of protein synthesis. Not4 is involved in translational repression of transcripts that cause transient ribosome stalling. The absence of Not4 affected global translational repression upon nutrient withdrawal, enhanced the expression of arrested nascent polypeptides and caused constitutive protein folding stress and aggregation. Similar defects were observed in cells with impaired mRNA decapping protein function and in cells lacking the mRNA decapping activator and translational repressor Dhh1. The results suggest a role for Not4 together with components of the decapping machinery in the regulation of protein expression on the mRNA level and emphasize the importance of translational repression for the maintenance of proteome integrity.

Keywords: Ccr4–Not complex, Not4, protein homeostasis, ribosome stalling, translational repression

Introduction

Protein synthesis is controlled on multiple levels to maintain the integrity of the cellular proteome. Therefore, diverse quality control mechanisms evolved to prevent production of defective proteins, which are, for example, encoded by aberrant messenger RNAs (mRNAs) that arise from mutations or errors during transcription and mRNA processing. Translation of aberrant mRNAs commonly causes ribosome stalling, which is recognized by quality control systems that prevent further synthesis of faulty proteins. These systems include mRNA surveillance pathways that cotranslationally induce degradation of mRNAs and recycle stalled ribosomes (Graille & Seraphin, 2012).

The turnover of mRNA commonly involves deadenylation of the 3′ end and subsequent removal of the 5′ cap structure (decapping) to inhibit further translation initiation and allow for degradation by 5′–3′ exonucleases and the exosome (Weill et al, 2012). However, rapid deadenylation-independent decapping also plays a role in mRNA surveillance and provides an additional mechanism for translational control (Muhlrad & Parker, 1994).

In addition, a ribosome-bound protein quality control system was recently discovered that facilitates the degradation of arrested nascent polypeptides (Bengtson & Joazeiro, 2010; Brandman et al, 2012). A key component of this system is the E3 ubiquitin–protein ligase Ltn1. Ltn1 binds to disassembled 60S ribosomal subunits and ubiquitinates arrested polypeptides which result, for example, from the translation of non-stop (NS) mRNAs that lack an in-frame termination codon (Bengtson & Joazeiro, 2010). Ribosomes that translate NS mRNAs are thought to enter the 3′ poly(A)-tail where they become stalled by the synthesis of consecutive lysine residues. Such polybasic sequences likely induce ribosome stalling by electrostatic interactions within the ribosomal exit tunnel (Lu & Deutsch, 2008; Brandman et al, 2012; Charneski & Hurst, 2013).

In yeast, another E3 ligase, Not4, was suggested to be involved in cotranslational protein quality control (Dimitrova et al, 2009; Matsuda et al, 2014). Not4 is part of a large molecular assembly, the Ccr4–Not complex, which consists of at least nine core subunits (Ccr4, Caf1, Caf40, Caf130, Not1–5) (Chen et al, 2001). Among them, Not1 is essential for yeast viability and forms the scaffold of the complex (Maillet et al, 2000). The complex is evolutionarily conserved in eukaryotes and localizes to the nucleus and cytosol. In the nucleus, the Ccr4–Not complex has been implicated in the regulation of transcription, whereas an important cytosolic function involves the Ccr4 and Caf1 subunits, which constitute the major deadenylases of yeast cells and catalyse poly(A)-tail shortening of mRNAs to initiate their degradation (Tucker et al, 2001).

Not4 contains an N-terminal RING domain required for its ubiquitination activity (Mulder et al, 2007) and has been suggested to regulate the levels of the histone demethylase Jhd2, the catalytic subunit of the DNA polymerase-α Cdc17, the transcription factor Yap1, the nascent polypeptide-associated complex NAC and the ribosomal protein Rps7A (Panasenko et al, 2006; Mersman et al, 2009; Haworth et al, 2010; Gulshan et al, 2012; Panasenko & Collart, 2012). In addition, the deletion of NOT4 affects cellular protein homeostasis (Halter et al, 2014), and based on the observation that the levels of cotranslationally arrested polypeptides were increased in cells lacking Not4, it was proposed that Not4 ubiquitinates arrested nascent polypeptides to target them for proteasomal degradation (Dimitrova et al, 2009). In contrast, other studies suggest that deletion of NOT4 enhances ubiquitination of nascent chains and does not affect the degradation of arrested translation products (Bengtson & Joazeiro, 2010; Duttler et al, 2013). Given these contradictory results, the function of Not4 in cotranslational quality control remains unclear.

Here we demonstrate that Not4 plays a crucial role in cotranslational quality control; however, it does not contribute to the ubiquitination and turnover of arrested nascent polypeptides. Instead, our data indicate that Not4 is required for global translational repression under nutritional limitations and especially for repression of mRNAs that cause transient ribosome stalling. This function likely involves the decapping components Dhh1 and Dcp1. Thus, Not4-dependent translational repression adds an additional level of cotranslational quality control important for the maintenance of cellular protein homeostasis.

Results

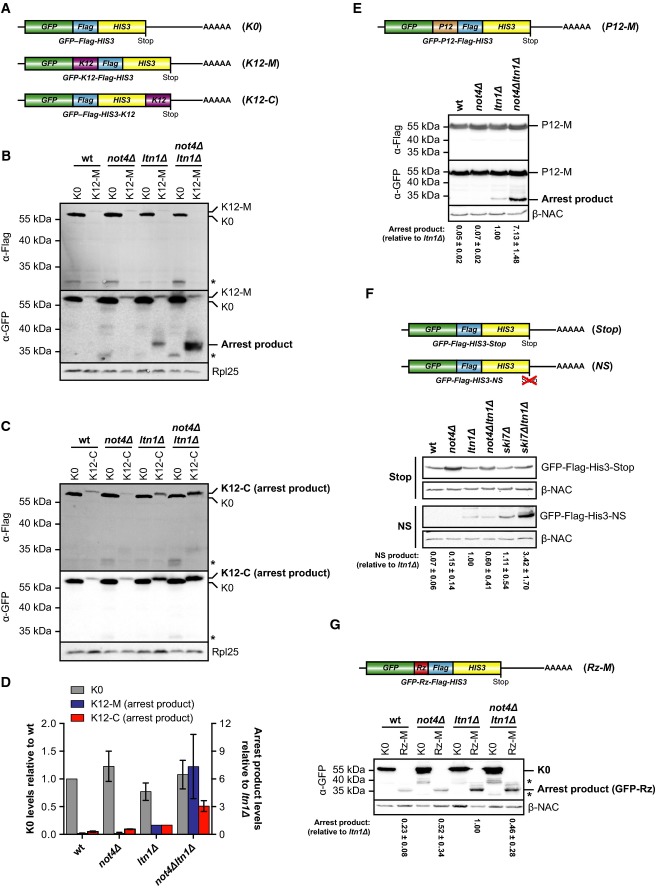

Not4 and its complex partners associate with polysomes

In yeast cells, Not4 has been shown to migrate with polysomes in sucrose gradients (Dimitrova et al, 2009), suggesting an interaction with ribosomal particles. To analyse this interaction in more detail, we prepared yeast cell lysates and separated the different ribosomal species by density gradient centrifugation. The gradient fractions were immunoblotted to detect Not4. Rpl25, a protein of the 60S ribosomal subunit, and the ribosome-associated chaperone Zuo1, which binds to the 60S subunit, were detected as controls. While Rpl25 and Zuo1 were present in all fractions containing 60S ribosomal subunits, the strongest signals for Not4 were found in late polysomal fractions (Fig1A).

Figure 1.

- Ribosomes from wild-type (wt) yeast lysates were separated on a 10-40% sucrose gradient. Top: Absorbance profile at 254 nm (A254). Bottom: Protein fractions were analysed by Western blotting using antibodies directed against the proteins indicated.

- Ribosomal particles from an RNase A-treated and untreated control lysate were separated by density gradient centrifugation. Top: A254 profiles. Bottom: Western blot analysis.

- not4Δ cells expressing HA-tagged Not4 (Not4-HA) from a plasmid were grown to an optical density (OD600) of 0.8. A lysate was prepared, and one half was treated with puromycin (Puro) to release nascent polypeptides and mRNA, while the other half was treated with cycloheximide (CHX) to stall translation. Samples were layered on top of a 20% sucrose cushion, and ribosomes were sedimented by ultracentrifugation. Ribosomal pellets were resuspended, and equal amounts of ribosomes were applied to Western blot analysis. Not4-HA was detected with antibodies directed against the HA-epitope tag. Rpl25 was detected as a loading control.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Caf1, another subunit of the Ccr4–Not complex, was distributed throughout the gradient, but the majority was also detected in late polysomal fractions (Fig1A). Moreover, HA-tagged versions of Ccr4, Not1 and Not5 showed a similar distribution (Supplementary Fig S1A), suggesting that the entire Ccr4–Not complex interacts with polysomes.

To confirm the interaction between the Ccr4–Not complex and polysomes, we treated wild-type cell lysate with RNase A prior to loading on sucrose gradients to degrade the mRNA and to convert polysomes into 80S monosomes (Fig1B). The Not4 and Caf1 signals shifted to the 80S fractions upon RNase A treatment and to the non-ribosomal top fractions. The same was observed for Zuo1 (Supplementary Fig S1B). Moreover, the association of Not4 and Caf1 with ribosomal particles was lost upon ribosome disassembly by puromycin treatment, indicating that the Ccr4–Not complex interacts specifically with assembled (poly)ribosomes carrying nascent polypeptides and mRNA (Fig1C).

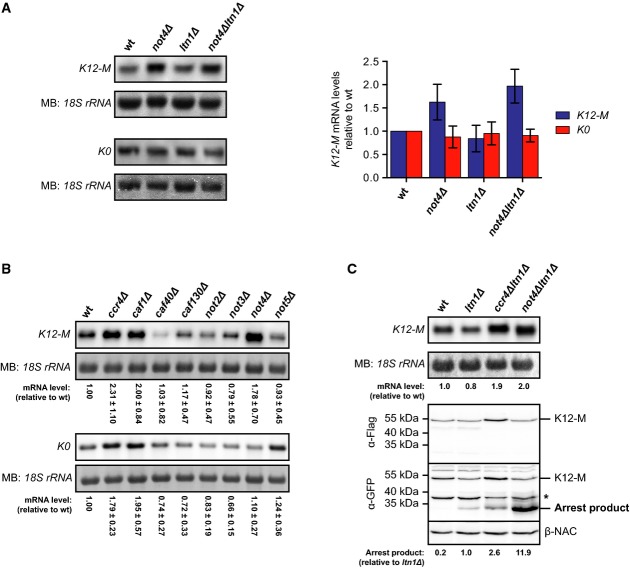

Not4 inhibits the expression of polylysine-arrested proteins

Polysomes consist mainly of translating ribosomes but can also contain large jammed assemblies that result from stalling events when ribosomes encounter obstacles during their migration along mRNAs. As Not4 interacted predominantly with very large polysomes, we hypothesized that it might be recruited to stalled ribosomes. Ribosome stalling leads to subunit disassembly followed by Ltn1-mediated ubiquitination of the nascent chains and their proteasomal degradation (Bengtson & Joazeiro, 2010; Brandman et al, 2012; Shao & Hegde, 2014). To investigate whether Not4 plays a role during cotranslational quality control, we analysed the expression of arrested polypeptides in the presence and absence of Not4 and Ltn1 using reporter proteins that transiently stall ribosomes during translation. These reporters consisted of an N-terminal GFP moiety fused to a Flag-tag and the His3 protein (Fig2A). To induce ribosome stalling, twelve consecutive lysine residues (K12) were either inserted between GFP and the Flag-tag (GFP-K12-Flag-His3; called hereafter K12-M) or fused to the C-terminal end (GFP-Flag-His3-K12; called hereafter K12-C). The same protein without a lysine stretch (K0) served as a non-arrested reporter. The levels of the K0 and K12 polypeptides in wild-type and mutant cells were then analysed by immunoblotting with antibodies directed against GFP and the Flag-tag to detect arrest products and full-length proteins.

Figure 2.

Not4 inhibits expression of polybasic translation arrest products

- A Schematic of mRNA encoding the non-stalling GFP-Flag-His3 (K0) control construct or ribosome-stalling constructs where twelve consecutive lysine residues were inserted between GFP and Flag (GFP-K12-Flag-His3; K12-M) or fused to His3 (GFP-Flag-His3-K12; K12-C).

- B, C Yeast cells transformed with centromeric plasmids expressing either K0 construct or K12-M (B) or K12-C ribosome-stalling construct (C) were grown in SCD −His to an optical density (OD600) of 0.8, and normalized lysates were analysed by Western blotting. Full-length proteins and translation arrest products were detected with GFP-specific (α-GFP) and Flag-specific (α-Flag) antibodies. Rpl25 was detected as a loading control. The asterisk marks degradation products.

- D Quantification of full-length K0 levels (n = 6, plotted on the left y-axis) as well as K12-M (n = 6) and K12-C (n = 3) arrest product levels (plotted on the right y-axis) from independent experiments as shown in (B) and (C). The values were normalized to the loading control, and arrest product levels are expressed relative to ltn1Δ cells (set to 1). Mean ± SD bars are shown.

- E Top: Schematic of mRNA encoding the P12-M polyproline ribosome-stalling construct GFP-P12-Flag-His3. Bottom: Same experiment as in (B) performed with P12-M and β-NAC was detected as a loading control. Arrest product levels were quantified as in (D). Shown is mean ± SD (n = 3).

- F Top: Schematic of mRNA with a HIS3 3′ untranslated region as described in Ito-Harashima et al (2007) encoding GFP-Flag-His3 fusion protein (Stop) or non-stop (NS) protein. Bottom: The experiment was performed as in (B) with Stop and NS constructs. β-NAC was detected as a loading control. Arrest product levels were quantified as in (D). Shown is mean ± SD (n = 5).

- G Top: Schematic of the Rz-M mRNA containing a self-cleavable hammerhead ribozyme sequence (Rz; red) inserted into the open reading frame. Bottom: The experiment was performed as in (B) with the Rz-M construct. β-NAC served as a loading control. Arrest product levels were quantified as in (D). Shown is mean ± SD (n = 3). Asterisks mark a degradation product of K0.

Source data are available online for this figure.

While the K0 reporter was produced in all strains at similar levels, no or only weak signals for both K12 arrest products were detected in wild-type and not4Δ cells, indicating that the arrested nascent chains were efficiently degraded (Fig2B, C and quantified in D). As observed earlier (Bengtson & Joazeiro, 2010), the levels of K12-arrested proteins were increased in cells lacking Ltn1. Strikingly, the signals of the arrest products were strongly enhanced up to the level of non-arrested K0 proteins when Not4 and Ltn1 were both absent (not4Δltn1Δ) (Fig2B–D). Moreover, most stalled K12-M polypeptides detectable in ltn1Δ and not4Δltn1Δ cells were still bound to ribosomes although a significant portion of K12-M peptides was released into the supernatant in not4Δltn1Δ cells (Supplementary Fig S2).

The polylysine stretches of released K12-M and K12-C arrest products may provide exposed ubiquitination sites that could unequally influence their posttranslational stability in the different knockout strains. We could rule out this possibility since polyproline-induced ribosome stalling (Gutierrez et al, 2013) using a P12-M construct (GFP-P12-Flag-His3) similarly increased arrest product levels in the ltn1Δ and ltn1Δnot4Δ mutants, even though the arrest was much weaker compared to the K12-M construct as evident by efficient production of full-length protein in all strains (Fig2E).

Taken together, the data show that the loss of Not4 in addition to Ltn1 enhanced the expression of arrested nascent polypeptides and increased ribosome stalling and subsequent release of truncated polypeptides. Thus, defective polypeptides can escape cotranslational quality control in the absence of Not4 and Ltn1 and accumulate in the cytosol.

Since ribosome stalling on K12 or P12 sequences is transient, we analysed whether Not4 also inhibits the expression of arrested polypeptides when ribosomes encounter insurmountable obstacles. Translation of non-stop (NS) mRNAs, which lack an in-frame stop codon, likely proceeds into the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) and the poly(A)-tail where ribosomes become stalled by the synthesis of long polylysine sequences or on the 3′ end of the mRNA, leading to destruction of the transcript (Inada & Aiba, 2005) and degradation of the nascent chain (Ito-Harashima et al, 2007). According to previous observations (Bengtson & Joazeiro, 2010), the level of NS proteins was enhanced in ltn1Δ mutants (Fig2F). However, the combined deletion of NOT4 and LTN1 did not further increase NS protein levels. As a positive control, we included cells lacking Ski7, a protein that plays a role in NS mRNA surveillance (van Hoof et al, 2002) and inhibits NS protein expression (Bengtson & Joazeiro, 2010). Deletion of SKI7 indeed increased NS protein levels, and this effect was stronger in ski7Δltn1Δ mutants (Fig2F).

We also analysed ribosome stalling at the end of truncated mRNAs by introducing a self-cleaving RNA segment, the hammerhead ribozyme (Rz), between the GFP- and Flag-encoding sequence to obtain the GFP-Rz-Flag-His3 fusion construct (Rz-M, Fig2G). The Rz sequence cuts the mRNA site specifically in cis after transcription, which generates truncated mRNAs that cause ribosome stalling at the cleavage site (Tsuboi et al, 2012). Thus, the translation arrest product (GFP-Rz) of the construct can be detected by GFP-specific antibodies. Expression of GFP-Rz was weak in wild-type and not4Δ cells and increased in cells lacking Ltn1 (Fig2G). Simultaneous deletion of NOT4 and LTN1 did not further increase the level of arrested polypeptides (the level was rather decreased relative to ltn1Δ).

We conclude that whereas in general Ltn1 is required to prevent the accumulation of translation arrest products, Not4 acts more specifically and inhibits the expression of transiently arrested proteins, but not of those that result from ribosome stalling on NS or truncated mRNAs. Translation arrest on NS or truncated mRNAs is likely stronger, and the topology of stalled ribosomes on the 3′ end of an mRNA is different and thus may require other quality control mechanisms.

Not4 functions in translational repression

Not4 could inhibit the expression of transiently arrested polypeptides by different mechanisms including: (i) destabilization of arrest products, (ii) translational repression or (iii) enhanced turnover of mRNAs that cause ribosome stalling.

The observation that deletion of NOT4 alone does not increase arrest product levels challenges the hypothesis that Not4 contributes directly to the degradation of arrested polypeptides. Accordingly, the stability of K12-M and P12-M arrest products was similar in ltn1Δ and not4Δltn1Δ cells (Supplementary Fig S3) and thus does not explain the strong increase of arrest product levels in not4Δltn1Δ mutants.

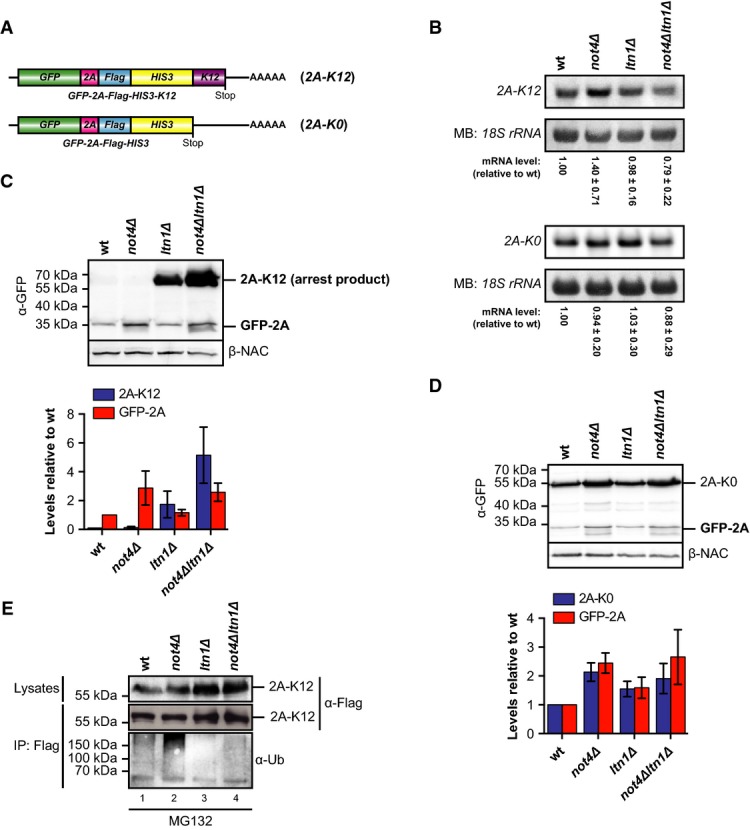

An alternative scenario could be that Not4 contributes to translational repression, which restricts arrest product synthesis. To investigate this possibility, we analysed the effect of Not4 on K12 reporter synthesis independent from degradation of the arrested products. We thus generated constructs which contain the 2A sequence of FMDV (foot-and-mouth disease virus) (Fig3A). Insertion of 2A between GFP and Flag induces polylysine-independent ribosome pausing at the end of the 2A-encoding sequence and rapid release of a GFP-2A fragment from a subset of nascent chains, followed by translation “re-initiation” and synthesis of the downstream products by the same ribosomes (Donnelly et al, 2001; Doronina et al, 2008). Therefore, the GFP-2A levels report on translation efficiency regardless of the stability of the full-length protein (Ito-Harashima et al, 2007). As the 2A-arrested product is cotranslationally released, it should escape destabilization by Ltn1 and thus reveal the effect of Not4 on reporter translation.

Figure 3.

Not4 acts in translational repression

- A Schematic of mRNA encoding the reporter constructs GFP-2A-Flag-His3 (2A-K0) and GFP-2A-Flag-His3-K12 (2A-K12) containing an in-frame insertion of the FMDV 2A sequence.

- B Northern blot analysis of 2A-K12 and 2A-K0 mRNA levels in yeast cells. The membrane was stained with methylene blue (MB) to visualize the 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) as a loading control. The reporter mRNA signals were quantified and normalized to the loading control. Shown is mean ± SD (n = 4 for 2A-K12 and n = 5 for 2A-K0).

- C, D Lysates of yeast cells expressing 2A-K12 (C) or 2A-K0 (D) were analysed by Western blotting with antibodies against GFP (α-GFP) and β-NAC. Bar graph: Western blot signals of full-length proteins and GFP-2A of three independent experiments were quantified, normalized to the loading control and expressed relative to values in wild-type (wt) cells. Shown is mean ± SD (n = 3).

- E Yeast cells were transformed with a plasmid expressing the ribosome-stalling construct 2A-K12. Cells were grown in SCD −His medium to the mid-log phase and treated with MG132. Lysates were prepared and the fusion proteins were immunoprecipitated. Samples of the lysates and the precipitated proteins were analysed by Western blotting. Proteins were detected with Flag-specific antibodies, and ubiquitination was detected with ubiquitin-specific (α-Ub) antibodies. Similar results were obtained in at least two separate experiments.

Source data are available online for this figure.

We analysed the expression of GFP-2A-Flag-His3-K12 (2A-K12) containing a K12-stalling sequence at the C-terminus, and GFP-2A-Flag-His3 (2A-K0), which lacks a C-terminal stalling sequence (Fig3A). The mRNA levels of both constructs were similar in all strains, and only the 2A-K12 mRNA levels were slightly elevated in not4Δ cells (Fig3B). In agreement with the data shown above, arrested full-length 2A-K12 protein could only be detected in ltn1Δ cells (Fig3C) and the signal was further enhanced in not4Δltn1Δ mutants, whereas full-length 2A-K0 was expressed in all strains (Fig3D). Importantly, the N-terminal GFP-2A fragment of 2A-K12 and 2A-K0 was produced in all strains independent of LTN1 deletion albeit detectable only at lower levels (Fig3C). Nevertheless, the GFP-2A levels of the 2A-K12 and 2A-K0 reporter constructs were significantly elevated (∼2- to 3-fold) in not4Δ and not4Δltn1Δ mutants (Fig3C and D). A similar tendency was observed for full-length 2A-K0, whereas the levels of the K0 construct which lacks the 2A element were less increased in these strains (compare Figs3D and 2D). Thus, loss of Not4 enhanced the synthesis of 2A-containing proteins independent of Ltn1. Together, these data are consistent with a role of Not4 in translational repression induced by transient ribosome stalling within open reading frames.

Our results furthermore disfavour a function of Not4 in degradation of arrested polypeptides. To investigate this directly, we analysed ubiquitination of 2A-K12 proteins. Cells were treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 prior to lysis to prevent degradation of arrested nascent chains, and therefore, full-length 2A-K12 was detected in wild-type and not4Δ cells (Fig3E). 2A-K12 proteins were then immunoprecipitated and analysed for ubiquitination. 2A-K12 ubiquitination was detected in wild-type cells but not in ltn1Δ mutants (Fig3E; Bengtson & Joazeiro, 2010; Brandman et al, 2012). In contrast, 2A-K12 ubiquitination was strongly enhanced in not4Δ cells, which is consistent with increased reporter synthesis in the absence of Not4 but argues further against a role of Not4 in ubiquitination of arrested polypeptides. The simultaneous deletion of LTN1 and NOT4 reduced ubiquitination of 2A-K12 proteins back to the level of ltn1Δ cells. This again implies that Ltn1 ubiquitinates arrested K12 proteins, whereas Not4 does not. In addition, expression of the E3 ligase-deficient mutant Not4-L35A (Mulder et al, 2007) efficiently reduced arrest product levels in not4Δltn1Δ cells to the ltn1Δ level (Supplementary Fig S4), suggesting that Not4-mediated inhibition of arrest product expression does not require its E3 ligase activity.

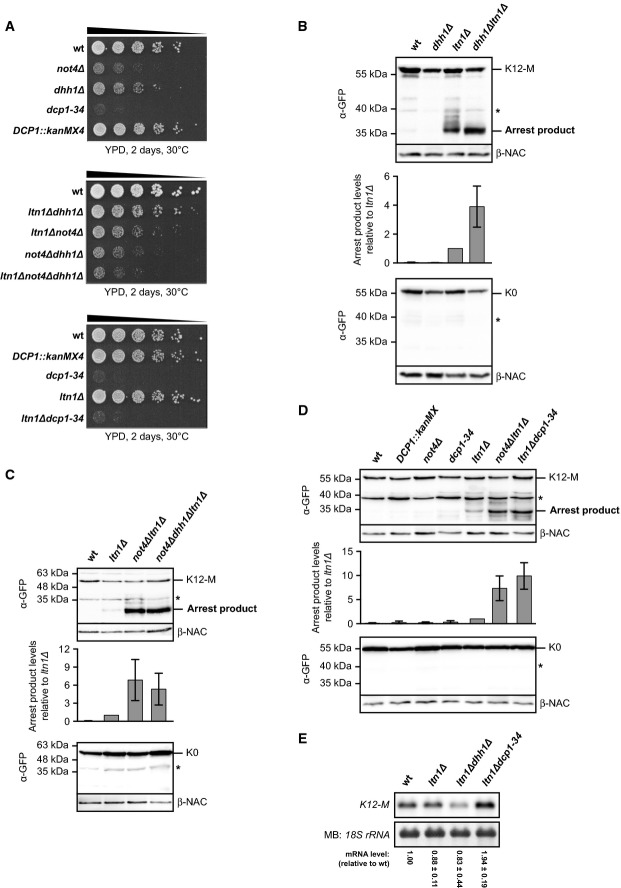

Altered mRNA levels have a minor effect on the expression of polylysine-arrested polypeptides

We observed increased expression and ubiquitination of K12-arrested polypeptides in the absence of Not4 and assumed that this is due to a loss of translational repression. However, it has been shown earlier that mutations that interfere with mRNA decay enhance protein expression and accordingly cotranslational ubiquitination (Duttler et al, 2013). We therefore addressed whether Not4 influences steady-state mRNA levels of the K12-M reporter since the arrest products of this construct were strongly enhanced in not4Δltn1Δ cells (Fig2B and D). Indeed, the levels of the K12-M mRNA were elevated about twofold in the absence of Not4, while the levels of the non-stalling K0 mRNA were similar in all strains (Fig4A). Thus, increased mRNA levels may contribute to enhanced K12-M protein expression in not4Δltn1Δ cells and hence to increased ribosome stalling and nascent chain ubiquitination. The mRNA half-lives of both, the K0 and K12-M mRNAs, were moderately elevated in the absence of Not4, which may explain the increased levels of the K12-M mRNA in not4Δ cells (Fig4A; Supplementary Fig S5). This also indicates that minimal sequence changes, such as introduction of the K12-encoding sequence, can cause differences in mRNA stabilities and levels in the different strains.

Figure 4.

Altered mRNA levels have a minor influence on expression of arrested proteins

- Northern blot analysis of K12-M or K0 mRNA levels in yeast cells. The membrane was stained with methylene blue (MB) to detect the 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) as a loading control. Bar graph: The mRNA signals were quantified, normalized to the loading control and expressed relative to wild-type (wt). Shown is mean ± SD (n = 4 for K12-M and n = 3 for K0).

- Northern blot analysis as in (A) of K12-M and K0 mRNA levels in ccr4–not mutants. Shown is mean ± SD (n = 4 for K12-M and n = 3 for K0).

- Parallel analysis of K12-M mRNA levels (top) and K12-M protein levels (bottom). Northern blot analysis was performed as in (A). GFP- (α-GFP) and Flag-specific (α-Flag) antibodies were used to detect reporter proteins by Western blotting. Arrest product levels were normalized to the β-NAC control signals. The asterisk marks non-specific bands. Similar results were obtained in three separate experiments.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Since Not4 is part of the Ccr4–Not complex, we analysed reporter mRNA levels also in other ccr4-not mutants, including cells lacking the major mRNA deadenylases Ccr4 and Caf1 (Fig4B). We found that the mRNA levels of K12-M were similarly increased in not4Δ mutants and in cells lacking Ccr4 and Caf1. However, in contrast to not4Δ cells, also the K0 mRNA signals were increased in ccr4Δ and caf1Δ mutants, respectively. This agrees well with a general role of Ccr4 and Caf1 in mRNA decay and suggests a more specific effect of Not4 on the stability of ribosome-stalling mRNAs.

We then directly compared the effects of NOT4 or CCR4 deletion on K12-M mRNA levels and the levels of the corresponding translation arrest product in the absence of Ltn1. K12-M mRNA levels were similarly increased in ccr4Δltn1Δ and not4Δltn1Δ cells, whereas the arrest product levels were only moderately enhanced in ccr4Δltn1Δ mutants compared to ltn1Δ cells (Fig4C). Only the combined deletion of LTN1 and NOT4 resulted in a strong increase of arrest product levels. Thus, although K12 mRNA levels influence reporter expression, they do not account for the strongly elevated K12 protein levels in not4Δltn1Δ mutants. This suggests that the effect of Not4 on the expression levels of K12-arrested polypeptides is mainly caused by translational repression.

Not4 and decapping proteins are required for fast global translational repression upon nutrient withdrawal

To further investigate the potential role of Not4 in translational repression, we took advantage of earlier observations that cells repress overall translation in response to a variety of stresses to prevent accumulation of defective proteins. It is known that yeast cells lacking the mRNA decapping proteins Dcp1 and Dcp2 as well as the decapping activator Dhh1 show defects in fast translational repression upon nutrient withdrawal (Holmes et al, 2004; Coller & Parker, 2005), a condition that rapidly reduces the cellular concentration of aminoacyl-tRNAs and may promote ribosome stalling. Interestingly, a physical interaction between the Ccr4–Not complex and Dhh1 has been reported in yeast (Hata et al, 1998; Coller et al, 2001; Maillet & Collart, 2002; Rouya et al, 2014). Therefore, we investigated whether loss of Not4 or Dhh1 causes a defect in translational repression after nutrient withdrawal.

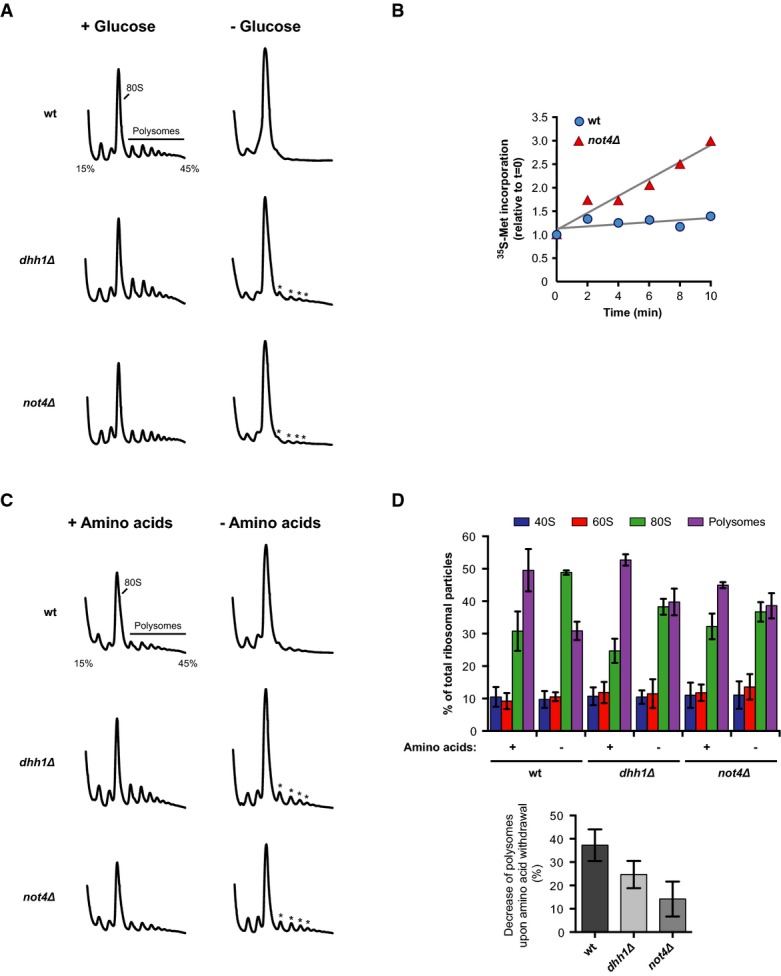

Glucose depletion caused the rapid conversion of polysomes into 80S monosomes in wild-type cells, reflecting severe reduction of translation activity (Fig5A). In contrast, residual polysome peaks were still detected in dhh1Δ mutants after glucose withdrawal, which agrees well with the reported defect in translational repression. Importantly, cells lacking Not4 showed a similar defect (Fig5A) and the relative rate of protein synthesis upon glucose depletion was higher in not4Δ mutants than in wild-type cells (Fig5B). Translational repression in dhh1Δ and not4Δ cells was also affected shortly after amino acid withdrawal as evident by the smaller decrease of polysomes (Fig5C and D). These data suggest that Dhh1 and Not4 are both important for fast translational repression during nutrient starvation.

Figure 5.

Not4 is required for fast translational repression in response to nutrient withdrawal

- A Polysome profiling with wild-type (wt) or mutant yeast cells. Absorbance traces at 254 nm (A254) are shown. Cells were grown to an optical density (OD600) of 0.5 in YPD, pelleted, resuspended in YP with or without 2% glucose and incubated for 10 min. Translation was stopped by the addition of cycloheximide, and cells were collected for polysome profiling on 15–45% sucrose gradients.

- B 35S-methionine incorporation into proteins after glucose depletion. Cells were grown in SCD medium to OD600 0.5 and transferred to SC labelling medium without glucose containing radioactive 35S-methionine. Cells were incubated for 10 min and samples were taken. TCA-precipitable radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation counting. Translation activity is given as incorporated radioactivity relative to t = 0. Best-fit trendlines are shown in grey.

- C, D Polysome profiling of wt and mutant cells as in (A). Cells were grown in SCD medium to OD600 0.5 and transferred to SCD or yeast nitrogen base (YNB) containing 2% glucose without amino acids. Cells were incubated for 10 min prior to polysome analysis. Quantitative analysis of individual ribosome species is shown in (D) with mean values ± SD (n = 3).

Source data are available online for this figure.

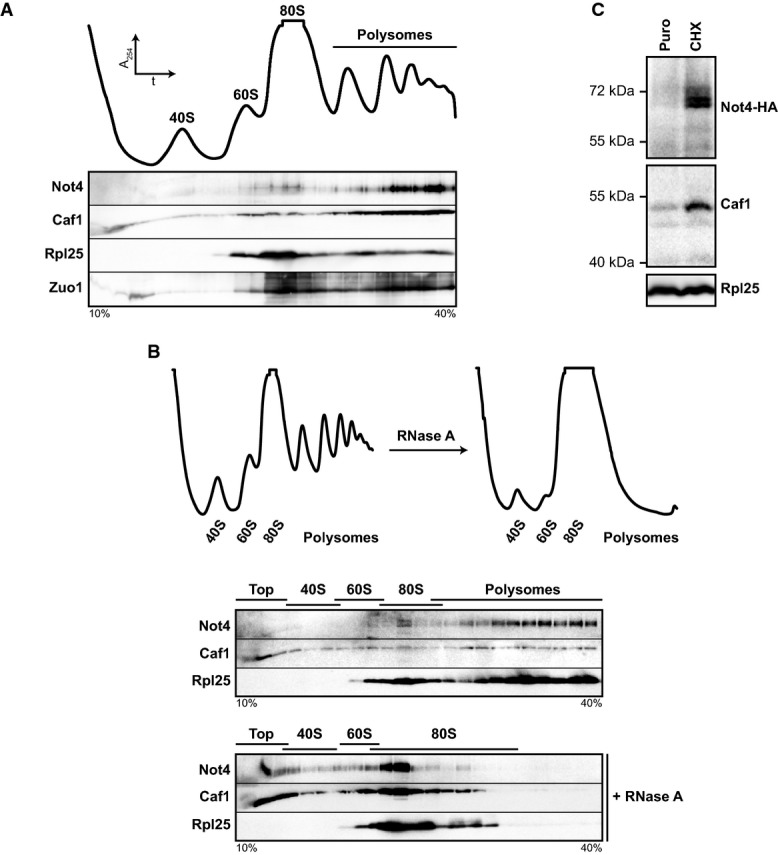

Not4 and decapping proteins are required for translational repression during ribosome stalling

Based on the similar defects of cells lacking Not4 or Dhh1 in global translational repression upon nutrient withdrawal, we investigated whether loss of Dhh1 and Dcp1–Dcp2 decapping complex function might also increase expression of translation arrest products at normal growth conditions. As we were unable to delete DCP1 or DCP2 in our yeast strain, we introduced a genomic point mutation in DCP1 (dcp1-34), which causes strong loss of function (Tharun & Parker, 1999). Growth of dhh1Δ cells was only slightly impaired at 30°C, whereas not4Δ and dcp1-34 mutants had a pronounced growth defect (Fig6A). Insertion of a kanMX cassette at the DCP1 locus, which was required for dcp1-34 construction, did not affect growth. Further mutational analysis revealed that not4Δdhh1Δ double mutants were viable in our strain background and showed only a slightly increased growth defect (Fig6A).

Figure 6.

Not4 and Dhh1 act in transcript-specific translational repression

- A Spot assay to monitor growth defects of mutant yeast cells. Cells were adjusted to an optical density (OD600) of 0.5, and 5-fold serial dilutions were spotted onto YPD plates. The plates were incubated as indicated.

- B–D The ribosome-stalling K12-M or the non-stalling K0 control construct was expressed in wild-type (wt) and mutant yeast cells. Normalized lysates were applied to Western blot analysis. Full-length proteins and translation arrest products were detected with GFP-specific (α-GFP) antibodies. β-NAC was detected as a loading control. The asterisk indicates unspecific bands. Bar graph: Arrest product levels of three experiments were quantified, normalized to the loading control and expressed relative to ltn1Δ. Shown is mean ± SD (n = 3 in B; n = 6 in C and D).

- E Northern blot analysis of K12-M levels. The membrane was stained with methylene blue (MB) to visualize the 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) as a loading control. The reporter mRNA signals from independent experiments were quantified and normalized to the loading control. Shown is mean ± SD (n = 3).

Source data are available online for this figure.

To investigate translation arrest product levels in the decapping mutants, we additionally deleted LTN1, which did not significantly influence the growth defects (Fig6A). Whereas no K12-M arrest products were detected in dhh1Δ cells, the combined deletion of DHH1 and LTN1 increased the level of K12-M arrest products compared to ltn1Δ cells, but not the level of the non-arrested K0 proteins (Fig6B). Moreover, deletion of LTN1, NOT4 and DHH1 altogether did not further increase the K12-M arrest product level relative to not4Δltn1Δ mutants (Fig6C), suggesting that Dhh1 and Not4 act in the same pathway of translational repression. As anticipated, the K12-M arrest product level was also increased in ltn1Δdcp1-34 cells, whereas no arrest products were detected in dcp1-34 single mutants (Fig6D). The K12-M mRNA levels were only increased in ltn1Δdcp1-34 cells (∼2-fold), but not in dhh1Δltn1Δ mutants (Fig6E). Thus, Dhh1 and decapping proteins contribute to inhibition of the synthesis of polybasic proteins. The strong correlation in function and the reported physical association of Dhh1 with the Ccr4–Not complex suggest that the decapping factors Dhh1 and Dcp1 operate together with Not4 in the same pathway. This agrees also with the observed dynamic interaction of Dhh1 with polysomes (Sweet et al, 2012). Accordingly, we found HA-tagged Dhh1 (Dhh1-HA) comigrating with polysomes in sucrose gradients (Supplementary Fig S6). Dhh1-HA associated with polysomes also in not4Δ cells but the signals appeared weaker, suggesting that Not4 may influence the association of Dhh1 with polysomes. Taken together, these results point to a role of Not4 together with decapping proteins in global and ribosome stalling-induced translational repression.

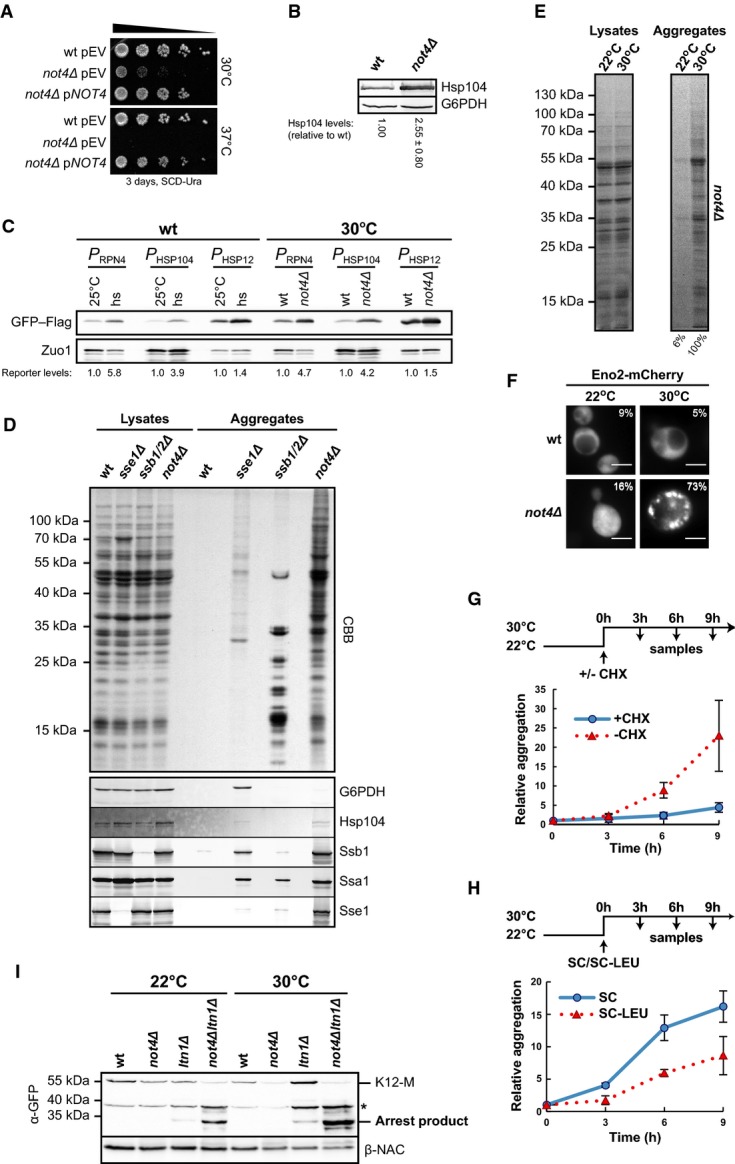

Not4 and decapping factors are required for the maintenance of cellular protein homeostasis

Regulation of protein synthesis and cotranslational quality control are critical to facilitate the coordinated supply of new and functional proteins according to cellular demand. We thus addressed whether deregulated translation in not4Δ cells interferes with protein homeostasis. Indeed, cells lacking Not4 were unable to grow at elevated temperature (Fig7A) and expression of the stress-inducible chaperone Hsp104 was enhanced in not4Δ cells at 30°C (Fig7B). Induction of the protein stress response was confirmed with reporter constructs consisting of stress-responsive promoters of three different genes (HSP12, RPN4 and HSP104) fused to a GFP–Flag-encoding sequence (Fig7C), indicating constitutive folding stress in not4Δ cells. Moreover, we detected severe aggregation of proteins distributed over a broad molecular weight range in not4Δ cells at 30°C and aggregates were enriched in proteins larger than 30 kDa (Fig7D). As a control, we included the analysis of cells lacking the chaperones Ssb1/Ssb2 or Sse1 where predominantly small ribosomal proteins or larger-sized proteins aggregate, respectively [Fig7D and (Koplin et al, 2010)]. Mass spectrometry analysis identified more than 500 proteins in the insoluble fraction of not4Δ mutants (Supplementary Table S1) including some molecular chaperones such as Hsp104, Ssa1, Sse1 and Ssb1/2, which was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig7D). It is difficult to distinguish between aggregated proteins that are directly affected by the absence of Not4 and those that are affected indirectly, for example due to the loss of a binding partner. Nevertheless, sequence analysis of the aggregation-prone protein species revealed no obvious common characteristics, such as enhanced hydrophobicity or enrichment of low-complexity regions, compared to the non-aggregated yeast proteins. However, the mean protein length of aggregated proteins was increased (621 aa for aggregated proteins vs. 412 aa for non-aggregated proteins; Supplementary Fig S7A), which is consistent with the enrichment of larger proteins in the insoluble fraction of not4Δ cells (Fig7D). In addition, sequence comparison with genome-wide mRNA translation profile data (Arava et al, 2003) revealed that the mean number of ribosomes associated with mRNAs of aggregated proteins was elevated (7 for the aggregated fraction vs. 5 for the non-aggregated fraction; Supplementary Fig S7B). This may reflect high translation rates since there was no obvious correlation between length of the mRNAs and the number of ribosomes associated with them (Supplementary Fig S7C).

Figure 7.

Deletion of NOT4 affects cellular protein homeostasis

- Wild-type (wt) and not4Δ cells with a complementation plasmid (pNOT4) or empty vector (pEV) were adjusted to an optical density (OD600) of 0.5, and 5-fold serial dilutions were spotted onto SCD −Ura plates. Plates were incubated as indicated.

- Cells were grown at 30°C to the mid-log phase, and Hsp104 levels were analysed in normalized lysates by immunoblotting. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) was detected as a loading control. Hsp104 signals were quantified and normalized to the loading control. Shown is mean ± SD (n = 4).

- Wt and not4Δ cells were transformed with plasmids encoding GFP–Flag. Expression was controlled by either one of three different heat-shock responsive promoters (P) derived from the HSP104, RPN4 and HSP12 genes (PHSP104, PRPN4 and PHSP12). Expression was analysed by Western blotting using Flag-specific antibodies. Immunodetection of Zuo1 served as a loading control. The signals were quantified and normalized to the loading control. Left: As a control, wt cells were grown at 25°C to OD600 0.8 and samples were taken before and 40 min after heat-shock (hs) at 38°C. Right: Wt and not4Δ cells expressing the reporter constructs were grown at 30°C to OD600 0.8 and samples were taken.

- Analysis of protein aggregation in wt and mutant yeast cells. Cells were grown in YPD to OD600 0.8, and protein aggregates were isolated from equal volumes of normalized lysates. The insoluble proteins and samples of the normalized lysates were separated by SDS–PAGE and visualized by CBB staining. Bottom: Parallel Western blot analysis of the total and aggregate fractions. G6PDH and the chaperones Hsp104, Ssb1, Ssa1 and Sse1 were detected.

- not4Δ cells were grown at 22°C or 30°C to OD600 0.8 and aggregates were analysed as in (D).

- Eno2-Flag-mCherry was expressed in wt and not4Δ cells at 22°C or 30°C and analysed by fluorescence microscopy. Numbers give the percentage of cells that showed discrete mCherry foci. Scale bars, 5 μm.

- not4Δ mutants were grown at 22°C to OD600 0.8 and shifted to 30°C with or without cycloheximide (CHX). Samples were taken at the indicated time intervals and aggregates were isolated for quantification. Mean values and SD bars of three experiments (n = 3) are shown.

- Leucine auxotrophic not4Δ mutants were grown at 22°C to OD600 0.8 and shifted to 30°C with or without leucine. Samples were taken and analysed as in (G). Shown is mean ± SD (n = 3).

- Expression of the K12-M reporter at 22°C and 30°C was analysed by Western blotting with antibodies against GFP (α-GFP) and β-NAC. The asterisk marks a non-specific band.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Much less insoluble proteins were isolated from not4Δ cells grown at 22°C compared to 30°C (Fig7E). To visualize aggregation in vivo, we fused a fluorescent Flag-mCherry moiety to enolase 2 (Eno2-Flag-mCherry), which was identified in the insoluble fraction of NOT4-deficient cells (Supplementary Table S1). The fusion protein formed multiple foci in not4Δ cells at 30°C but was homogenously distributed at 22°C (Fig7F). Thus, folding stress-induced aggregation can be ameliorated in not4Δ cells by reducing the growth temperature.

When cells were pre-grown at 22°C, where most proteins were soluble, and then shifted to 30°C to induce aggregation, the simultaneous addition of the translational inhibitor cycloheximide efficiently prevented protein aggregation, while insoluble proteins accumulated in cells without translational inhibition (Fig7G). This suggests that ongoing protein synthesis is causative for protein aggregation at 30°C in not4Δ cells. Similar results were obtained when protein synthesis was reduced by leucine depletion (Fig7H). Importantly, the turnover of newly made proteins was not significantly impaired in not4Δ cells (Supplementary Fig S8A) and LTN1 deletion had no influence on the accumulation of insoluble polypeptides (Supplementary Fig S8B), indicating that aggregation was not due to defects in cotranslational protein degradation. In addition, aggregation was not increased in cells lacking proteins involved in mRNA degradation such as Ccr4 and Caf1 or in the absence of the 5′–3′ exonuclease Xrn1 (Supplementary Fig S8C). Moreover, although almost no proteins aggregated in not4Δ cells at 22°C, inhibition of K12-M translation arrest product expression was still affected in ltn1Δ and not4Δltn1Δ mutants at 22°C (Fig7I). These data point to a strong correlation between misregulated protein synthesis and aggregation in the absence of Not4 and suggest that loss of Not4-dependent translational control causes severe protein folding stress.

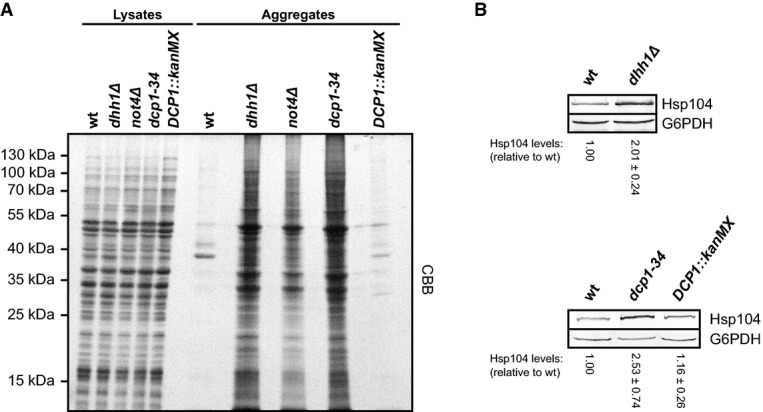

Finally, we hypothesized that if Not4 cooperates functionally with Dhh1 and Dcp1–Dcp2 during translational repression, the proteome integrity should be similarly disturbed in dhh1Δ and dcp1-34 cells. Indeed, strong protein aggregation was detected in dhh1Δ and dcp1-34 mutants and the pattern of insoluble proteins was very similar to NOT4-deficient cells (Fig8A). In addition, like in not4Δ cells, the Hsp104 chaperone levels were increased in dhh1Δ and dcp1-34 mutants (Fig8B), indicating constitutive folding stress. Thus, mutations that interfere with translational repression severely affect protein homeostasis.

Figure 8.

Decapping factors are required for the maintenance of cellular protein homeostasis

- Protein aggregation was analysed in wild-type (wt) and mutant yeast cells. Cells were grown in YPD to an optical density (OD600) of 0.8. Aggregated proteins were isolated from equal volumes of normalized lysates. Insoluble proteins and samples of the normalized lysates were separated by SDS–PAGE and visualized by CBB staining.

- Cells were grown to the mid-log phase at 30°C, and Hsp104 levels were analysed in normalized lysates by Western blotting. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) was detected as a loading control, and Hsp104 signals were quantified and normalized to the loading control. Shown is mean ± SD (n = 4).

Source data are available online for this figure.

Discussion

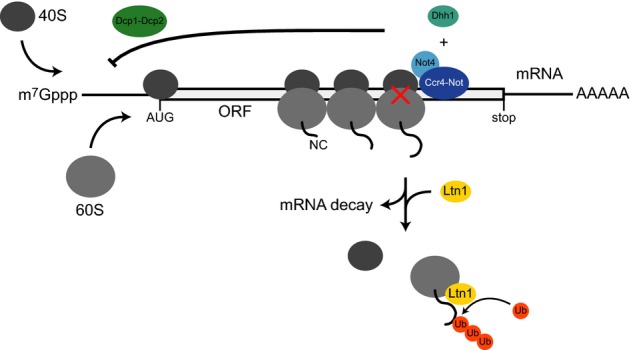

Although several key players of cotranslational quality control in eukaryotes have been identified recently, many details about their activities and their functional relationship remain elusive. Among those proteins are the two E3 ligases Not4 and Ltn1, which are conserved from yeast to humans and both have proposed functions in the turnover of arrested nascent polypeptides. Whereas Ltn1 is required for efficient cotranslational degradation of arrested nascent chains, we found that Not4 is involved in the negative regulation of translation (Fig9).

Figure 9.

Translational repression of ribosome-stalling mRNAs involves Not4, Dhh1 and the decapping factors Dcp1–Dcp2

Not4, together with the Ccr4–Not complex, associates with polysomes (grey) that likely contain stalled (red cross) and jammed ribosomes. Transient ribosome stalling on mRNAs within open reading frames (ORF) leads to Not4-dependent translational repression. The decapping activator Dhh1 and the decapping proteins Dcp1–Dcp2, which remove the 7-methylguanosine (m7Gppp) cap structure from the 5′ end of mRNAs, are also required for translational repression of ribosome-stalling mRNAs, suggesting that the Ccr4–Not complex and the decapping machinery act together in this process. Potential repression mechanisms include modulation of transcript-specific decapping or direct inhibition of translation initiation. This prevents further ribosome jamming and synthesis of arrested proteins. Upon disassembly of stalled ribosomes, the arrested nascent chains (NC) are ubiquitinated by Ltn1 to initiate their degradation and mRNAs may become eliminated.

The defects in overall translational repression upon nutrient withdrawal as well as severe translation-dependent protein folding stress in the absence of Not4 suggest that Not4 (and probably other components of the Ccr4–Not complex) plays a rather general role in translational repression important to maintain protein homeostasis.

Another important observation was that deletion of NOT4 in combination with LTN1 in particular increased the expression of translation arrest products. This result is based on the analysis of reporter constructs, which induce strong cotranslational ribosome stalling, for example by consecutive lysine residues. Likewise, ribosomes stall during translation of defective endogenous transcripts before the latter become recognized and eliminated by mRNA surveillance mechanisms (Shoemaker & Green, 2012). Apart from that, ribosome stalling may occur on various non-erroneous mRNAs, such as the ones with stable secondary structures, rare codons or regions encoding stretches of positively charged amino acids. Recent ribosome profiling data indicate that translation is rather inhomogeneous (Ingolia et al, 2011) and ribosomes stall transiently on many natural transcripts. In any case, ribosome stalling on mRNAs causes jamming of subsequent ribosomes, which leads to the formation of large polysomes. This agrees well with the finding that Not4 and also other subunits of the Ccr4–Not complex were enriched in the late polysomal fractions of sucrose gradients (Fig1; Supplementary Fig S1) and suggests that they may be specifically recruited to stalled ribosomes to repress further translation of the transcript and to prevent the accumulation of defective proteins (Fig9).

Not4 is assumed to locate adjacent to the mRNA deadenylases Ccr4 and Caf1 in the Ccr4–Not complex (Bai et al, 1999; Basquin et al, 2012). Not4 may thus not only repress translation of transcripts that cause ribosome stalling but also promote their deadenylation and turnover. We indeed observed moderately elevated levels of the ribosome-stalling K12-M mRNA in cells lacking Not4 (Fig4A), but our data suggest that differences in mRNA levels have a minor influence on the levels of translation arrest products (Figs3 and4). Moreover, the role of the E3-ligase activity of Not4 in cotranslational protein quality control is still unclear as deletion of NOT4 enhanced ubiquitination of transiently stalled nascent polypeptides and an E3 ligase-deficient mutant fully compensated the loss of Not4 function in translational repression.

To obtain more insights into how Not4 may contribute to translational repression of certain mRNAs, we searched for other proteins that are connected to the Ccr4–Not complex and function in translational repression. The DExD-box ATPase and decapping activator Dhh1 meets both criteria. Yeast Dhh1 interacts physically with the Ccr4–Not complex (Hata et al, 1998; Coller et al, 2001; Maillet & Collart, 2002) and contributes to translational repression (Coller & Parker, 2005). Moreover, an interaction between Dhh1 and polysomes has been described (Drummond et al, 2011) and components of the Ccr4–Not complex including Not proteins and Dhh1 localize to cytoplasmic foci called P-bodies (Muhlrad & Parker, 2005; Parker & Sheth, 2007), where turnover of translationally repressed mRNA takes place. Indeed, we found that also Dhh1 contributes to the repression of K12 protein synthesis (Fig6B). Since the efficiency of translation initiation depends on intact 5′ mRNA cap structures, it is possible that Not4 exerts its regulatory effect by modulating decapping or cap-dependent translation initiation through Dhh1 and the decapping enzymes (Fig9). It is known that the decapping holoenzyme Dcp1–Dcp2 is controlled by decapping activators and some of them recruit Dcp1–Dcp2 to specific transcripts (Li & Kiledjian, 2010). Moreover, decapping can occur during translation on polysomes (Hu et al, 2009, 2010) and thus allows for cotranslational as well as mRNA-specific translational repression. In addition, Not2, Not4 and Not5 have been implicated in stimulation of deadenylation-independent decapping of certain mRNAs (Muhlrad & Parker, 2005), which supports a function of Not4 in translational repression and decapping. This conclusion is further supported by the finding that dcp1-34 cells show similar defects in translational repression as not4Δ and dhh1Δ mutants.

Translation initiation and mRNA decapping are competing processes. Accordingly, decapping can be directly inhibited by cap-binding translation initiation factors which dissociate from transcripts before decapping occurs (Schwartz & Parker, 1999, 2000; Tharun & Parker, 2001). Although the mechanism for the latter process is still unclear, it likely marks the exit of an mRNA from translation before its degradation. Thus, Not4-dependent translational repression may occur more directly on the level of translation initiation, for example by inhibition or displacement of an initiation factor. Importantly, in vitro experiments suggest that Dhh1 primarily represses translation initiation, which then indirectly promotes decapping (Coller & Parker, 2005; Nissan et al, 2010), whereas other data suggest that Dhh1 rather inhibits translation elongation (Sweet et al, 2012).

Not4 and the Ccr4–Not complex repress translation of specific mRNAs in the germline of fruit flies (Kadyrova et al, 2007). In this and other cases, the Ccr4–Not complex is recruited to the 3′ UTRs of target mRNAs via pumilio family proteins (Goldstrohm et al, 2006; Van Etten et al, 2012). In animal cells, the Ccr4–Not complex acts in microRNA-mediated translational repression and deadenylation of specific transcripts (Cooke et al, 2010; Braun et al, 2011; Chekulaeva et al, 2011; Fabian et al, 2011) involving also Dhh1 orthologs (Chen et al, 2014b; Mathys et al, 2014; Rouya et al, 2014). The principal function of Ccr4–Not components in translational repression seems thus to be conserved. However, ribosome stalling-dependent translational repression in yeast cannot be explained by targeting of Not4 to specific sequences in the 3′ UTR and thus requires other recruitment signals. For example in metazoans, the translational repressor protein FMRP, which shows a similar distribution in polysome profiles as Not4 (Darnell et al, 2011), first binds to its target mRNAs and later during translation directly to ribosomes, where it likely inhibits elongation through steric effects (Chen et al, 2014a). The FMRP–ribosome interaction involves RNA-binding motifs. Not4 also contains a RNA recognition motif (RRM) raising the possibility of a similar mode of interaction. However, unlike FMRP, Not4 dissociates from ribosomes upon their disassembly with puromycin (Fig1C), indicating different interaction characteristics. In addition, Not4 recruitment could be mediated by another component of the Ccr4–Not complex. Interestingly, Not4 seems not to be a core subunit of the Ccr4–Not complex in metazoans (Lau et al, 2009; Temme et al, 2010), suggesting potential functional and mechanistic differences.

Deletion of either the NOT4 or DHH1 gene as well as a DCP1 mutation caused translational misregulation, constitutive folding stress and strong protein aggregation. These very similar defects in the different mutants suggest that: (i) Not4, Dcp1 and Dhh1 act in the same pathway, and (ii) that the loss of negative control during protein synthesis is causative for the proteostatic imbalance in these cells. The observation that aggregation in not4Δ cells can be ameliorated by inhibition of protein synthesis supports this assumption. Interestingly, we did not observe severe aggregation in cells lacking Ltn1 or in mutants with defective mRNA decay, suggesting that efficient backup systems exist that can substitute for these activities. In contrast, cells lacking Not4 cannot suppress protein aggregation although the heat-shock response is induced, emphasizing the unique function of Not4 in translational quality control and its importance for cellular protein homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains and growth conditions

All yeast strains used in this study were isogenic derivatives of BY4741 and BY4743 (Brachmann et al, 1998). Unless described otherwise, cells were grown under standard conditions at 30°C in YPD [1% (w/v) Bacto-yeast extract, 2% (w/v) Bacto-peptone, 2% (w/v) dextrose] or defined synthetic complete (SC) media (6.7 g/l Bacto-yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 2 g/l SC amino acid mix) containing 2% (w/v) glucose (SCD) (Guthrie & Fink, 2002; Amberg et al, 2005). Spot assays were performed by adjusting yeast cultures to the same optical density (OD600), and fivefold serial dilutions were spotted onto agar plates. Plates were incubated as indicated.

Polysome profiling

Yeast cells were grown at 30°C in YPD medium to OD600 1.0. The culture was poured on crushed ice and harvested by centrifugation at 4°C in the presence of 100 μg/ml cycloheximide to stabilize translating ribosomes. Lysates were prepared by glass bead disruption (FastPrep-24, MP) of the yeast cells in lysis buffer [20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 100 mM potassium acetate, 2 mM magnesium acetate, 0.5 mM DTT, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 100 μg/ml cycloheximide, 1× Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)]. Afterwards, the lysates were cleared twice by centrifugation at 16,000 g at 4°C for 10 min and absorbance values at 260 nm (A260) were normalized with lysis buffer. Volumes of each lysate equivalent to eight A260 absorbance units were loaded onto an 11 ml 15–45% (w/v) sucrose gradient prepared with a gradient forming instrument (Gradient Master, Biocomp Instruments) in lysis buffer without PMSF and centrifuged in a TH-641 rotor (Sorvall) at 39,000 rpm for 2 h at 4°C. Upon centrifugation, the gradients were fractionated from the top with a gradient fractionator (Teledyne Isco, Inc.) and the A254 signals were recorded to detect the fractions containing soluble proteins, ribosomal subunits, 80S monosomes as well as polysomes. The absorbance data were processed with PeakTrak V1.1 (Teledyne Isco, Inc.), and ribosome species were quantified by calculating the area under the absorbance curve. The collected fractions were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid (TCA), and the proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE followed by Western blotting. Larger gradients were prepared where indicated. For that, volumes equivalent to 180–200 A260 units were loaded onto a 38 ml 10–40% (w/v) sucrose gradient and centrifuged in a SW28 rotor (Beckman) at 25,000 rpm for 7 h at 4°C. The readout was performed as described above. To disrupt polysomes, the lysates were treated with RNase A (Fermentas) at a final concentration of 300 μg/ml and incubated for 15 min on ice prior to density gradient centrifugation.

Analysis of translation arrest in vivo

Yeast cells were transformed with plasmids encoding ribosome-stalling reporter proteins and grown to the exponential phase in SCD −His medium. Cells were lysed by glass bead disruption in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 100 mM potassium acetate, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 2× Complete protease inhibitor mix) and analysed by SDS–PAGE and Western blotting.

Nutrient withdrawal experiments

Nutrient withdrawal experiments were performed as described in Ashe et al (2000) and Holmes et al (2004) with minor modifications. To analyse translational repression upon glucose depletion, yeast cells were grown in 1 l YPD to OD600 0.5. The culture was split and cells were sedimented at 1,000 g for 3 min at 30°C. The cells were then resuspended in 500 ml pre-warmed YP with or without 2% (w/v) glucose and incubated at 30°C. After 10 min translation was stopped with 100 μg/ml cycloheximide and cells were rapidly chilled by pouring the culture on crushed ice. The cells were harvested for polysome profiling as described above. Amino acid depletion was performed likewise except that cells were grown in SCD and resuspended in pre-warmed starvation medium [6.7 g/l Bacto-yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 2% (w/v) glucose] with or without 2 g/l SC amino acids.

Measurement of translation activity upon glucose withdrawal

Measurement of translation activity upon glucose depletion was performed as previously described (Ashe et al, 2000). Cells were grown in 20 ml SCD medium to OD600 0.5 at 30°C. A total of 2 OD600 units of cells were sedimented for 2 min at 1,000 g and resuspended in 10 ml pre-warmed labelling medium [SC −Met, 59.5 ng/ml methionine, 0.5 ng/ml 35S-methionine (1,000 Ci/mmol, Hartmann Analytic)] with or without 2% (w/v) glucose.

Isolation of protein aggregates

Aggregates were prepared as described previously (Koplin et al, 2010). Liquid yeast cultures were inoculated with stationary cells to OD600 0.1. Cells were grown in YPD at 30°C to OD600 0.8–1.0, harvested in 50 ml aliquots in the presence of 15 mM sodium azide and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. For cell lysis, the frozen pellets were resuspended in 1 ml buffer I [20 mM potassium phosphate pH 6.8, 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20, protease inhibitors, 1 mM PMSF, 1.25 U/ml DNase (Sigma)] containing 3 mg/ml Zymolyase-T20 (MP Biomedicals), incubated for 20 min at room temperature and chilled on ice. Upon sonication (Branson tip-sonifier; eight times at level 4 and 50% duty cycle), the samples were centrifuged for 20 min at 200 g and the protein concentrations of the supernatants were normalized in a final volume of 800 μl. A sample of each normalized lysate was taken as an input control. The aggregated proteins were sedimented at 16,000 g for 20 min. The pellets were washed twice with buffer II [20 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.8), protease inhibitors] containing 2% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, sonicated (six times at level 4 and 50% duty cycle) and centrifuged at 16,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. Finally, the aggregated proteins were washed in buffer II, suspended in sample buffer and separated by SDS–PAGE. The proteins were visualized by Coomassie staining and quantified using ImageJ64 (NIH).

Protein synthesis-dependent aggregation

To study protein synthesis-dependent aggregation, not4Δ cells were grown at 22°C to OD600 0.8 in YPD medium. A total of 300 μg/ml cycloheximide was added to half of the cells to stop protein synthesis, while the other half remained untreated. Both cultures were shifted to 30°C to induce protein aggregation. Samples were taken at different time points and aggregated proteins were extracted as described above. The aggregated proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE and quantified. Alternatively, not4Δ cells were grown at 22°C to OD600 0.8 in YPD medium and washed twice with sterile water. The cells were then resuspended in SCD medium with or without leucine (SCD −Leu) and shifted to 30°C (note that the yeast cells were leucine auxotrophic). Samples were taken at different time intervals and protein aggregates were isolated.

Ribosome cosedimentation assay

For the release of nascent peptides from ribosomes, yeast cells were grown in SCD medium without uracil (SCD −Ura) to OD600 1 and 40 OD600 units were collected by centrifugation. The cells were washed in SCD medium lacking uracil and methionine (SCD −Ura −Met), resuspended in SCD −Ura −Met and starved for 45 min at 30°C. To label nascent polypeptide chains and newly synthesized proteins, 20 μCi/ml of 35S-methionine (Hartmann Analytik) was added to the cells for 50 s. Afterwards, the cells were chilled on ice. Half of the cells were treated with 300 μg/ml cycloheximide to stabilize ribosome-nascent chain complexes, whereas the other half was incubated with 0.1 mM puromycin for 5 min on ice to release nascent polypeptides from ribosomes. The cells were then pelleted and lysed by glass bead disruption in buffer III (50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 100 mM potassium acetate, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 2× Complete protease inhibitor cocktail) with or without 300 μg/ml cycloheximide. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 16,000 g for 10 min at 4°C, protein concentrations were normalized, and a sample was taken. The lysate from the puromycin-treated cells was again incubated for 1 h with 0.6 mM puromycin on ice to increase the efficiency of nascent chain release. Next, equal volumes of the lysates were loaded onto a 20% (w/v) sucrose cushion prepared in buffer III with or without 300 μg/ml cycloheximide, respectively, and centrifuged for 90 min at 200,000 g at 4°C to sediment the ribosomes. Upon centrifugation, the ribosomes were resuspended in lysis buffer. The A260 values of the ribosome solutions were normalized and equal volumes were supplemented with SDS sample buffer. Volumes equivalent to 1.1 A260 units of ribosomes as well as 20 μg of the total samples were loaded per lane onto a gel and analysed by SDS–PAGE and Western blotting. To confirm the release of nascent chains by puromycin treatment, radioactive signals in the ribosomal pellet fractions were detected by autoradiography with the FLA-9000 system (Fujifilm). To analyse the ribosome association of translation arrest products, yeast cells were transformed with plasmids encoding the K12-M ribosome-stalling construct and the cells were cultured to the exponential phase in SCD −His medium. Cell lysates were prepared by glass bead disruption in lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 100 mM potassium acetate, 2 mM magnesium acetate, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 2× protease inhibitor mix). Volumes of lysates equivalent to 1.5 A260 units were diluted to 200 μl and loaded onto a 600 μl sucrose cushion [25% (w/v) sucrose in lysis buffer]. Ribosomes were pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 200,000 g for 90 min (rotor S140-AT; Sorvall) at 4°C and resuspended in SDS sample buffer. Samples of the normalized lysates and supernatants were precipitated with TCA and resuspended in alkaline SDS sample buffer. Aliquots of each fraction were analysed by SDS–PAGE and Western blotting.

Immunoprecipitation (IP)

Denaturing IP of K12 proteins was performed as described in Bengtson and Joazeiro (2010). Yeast cells were transformed with the plasmid p413GPD-GFP-2A-FLAG-HIS3-K12 and grown overnight in SCD −His medium containing 0.17% (w/v) yeast nitrogen base without ammonium sulphate and 0.1% (w/v) proline. The cells were used to inoculate fresh medium containing 0.003% (w/v) SDS to OD600 0.5 and grown for 3 h at 30°C. Afterwards, 75 μM MG132 was added for 30 min (Liu et al, 2007) and cells were collected. The cells were then incubated 5 min in 0.1% (w/v) NaOH at room temperature, pelleted, resuspended in lysis buffer [1% (w/v) SDS, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 8 μg/ml pepstatin A] and boiled. The cleared lysates were adjusted to a protein concentration of 4 μg/μl in 100 μl lysis buffer, diluted with 900 μl IP-buffer A [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 250 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% (v/v) NP40] and incubated with 25 μl anti-FLAG M2 magnetic beads (Sigma) for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with IP-buffer A, and bound proteins were eluted by boiling in 2× SDS sample buffer. Samples of the adjusted lysates and the IP eluates were analysed by Western blotting. Ubiquitinated proteins were detected with polyclonal anti-ubiquitin antibodies (Dako).

Northern blotting

Yeast cells were transformed with reporter plasmids and grown in SCD −His medium to OD600 0.8. Total RNA was extracted with the hot-phenol method (Schmitt et al, 1990) followed by ethanol precipitation. Equal amounts of RNA were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and transferred to a Biodyne A membrane (Pall Life Sciences). The membrane was stained with methylene blue to confirm equal loading. Digoxigenin (DIG)-labelled RNA probes were synthesized with the DIG RNA Labeling Kit (Roche), and mRNA was detected with reagents provided by the DIG Northern Starter Kit (Roche). The signals on the blots were detected with the LAS-3000 system (Fujifilm). The oligonucleotides 5′-GAACTCTTCACTGGAGTTGTCC-3′ and 5′-gatcTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGgtttgtctgccatgatgtatac-3′ were used to amplify template DNA for the T7-based in vitro synthesis of DIG-labelled GFP RNA probe. To determine mRNA half-lives, the K0 and K12-M reporter mRNAs were expressed under control of a galactose-inducible promoter (GAL1) on a centromeric plasmid [pRS316(GAL1)-GFP–Flag-HIS3 and pRS316(GAL1)-GFP-K12-Flag-HIS3], respectively. The cells were grown in SC −Ura medium containing 2% (w/v) galactose for steady-state expression of the reporter mRNAs to OD600 0.8 and transferred to SCD −Ura medium [supplemented with 2% (w/v) glucose] for transcriptional shut-off. Samples were taken at different time intervals and RNA was extracted for Northern blotting. The Northern blot signals were quantified and normalized to the 18S ribosomal RNA. Half-lives were determined by non-linear regression analysis using Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.) and calculated as described in Coller (2008) with the equation t1/2 = ln(2)/k, where k = rate constant for mRNA decay.

Stress reporter assay

Yeast cells were transformed with the plasmids p413PRPN4-GFP–Flag, p413PHSP12-GFP–Flag and p413PHSP104-GFP–Flag, respectively. Single clones were isolated and grown in SCD −His medium to OD600 0.8 at 25°C. To test the responsiveness of the reporter constructs to heat shock, a sample was taken from wild-type cells carrying the different plasmids before and after a temperature shift to 38°C for 40 min. To test for constitutive expression of the stress reporters in the wild-type and not4Δ strain, stationary overnight cultures were used to inoculate SCD −His medium to OD600 0.15 and the cultures were grown at 22°C or 30°C until OD600 0.8 was reached. Afterwards, the cells were pelleted, resuspended in FPB [50 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 100 mM potassium acetate, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 2× Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)] on ice and lysed by glass bead disruption. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 16,000 g for 2 min, and the protein concentrations were determined (Protein Assay, Bio-Rad). Fifteen micrograms of each lysate were loaded on a SDS gel. Expression of the GFP–Flag reporter constructs was detected by Western blotting.

Microscopy

For standard and fluorescence microscopy, yeast cells were grown in YPD to OD600 1 at 22°C or 30°C. Then, the cells were fixed by the addition of 4% (v/v) formaldehyde for 10 min and one OD600 unit of cells was pelleted. Microscopy was performed with a Visitron microscope (37081 Visitron Systems, Axio, Carl Zeiss Inc.) equipped with a 100× magnification Plan-Apochromat oil objective. All images were recorded at room temperature and in PBS (pH 7.4) as imaging medium. Fluorescence was observed using a FITC filter. Pictures were recorded with the Spot Pursuit camera (model 23.0) and 1.4 MP monochrome without irradiation. VisiView (Visitron Systems) was used as an acquisition software, and the images were processed with Photoshop CS3 (Adobe) and ImageJ64 (NIH).

Protein turnover experiments

The protocol for the measurement of protein turnover was adapted from Medicherla and Goldberg (2008) and Seufert and Jentsch (1990). Cells were grown in YPD to the exponential phase (OD600 0.5–0.8) at 30°C, washed and starved for 60 min in SCD −Met medium. 20 μCi/ml 35S-methionine was added for 5 min to label newly synthesized proteins. Protein synthesis was stopped with 0.5 mg/ml cycloheximide, cells were washed twice in ice-cold chase medium (SCD containing 0.5 mg/ml cycloheximide and 1 mg/ml methionine) and incubated in pre-warmed chase medium at 30°C. Samples were taken at different time intervals, and protein degradation was stopped by mixing with TCA at a final concentration of 10% (w/v) on ice. Radioactivity in the total sample and sample supernatant was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Protein degradation is given as the TCA-soluble fraction of total incorporated radioactivity released from cells during the chase period relative to t = 0.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Sachs, S. Zboron, J. Thielicke, A. Waizenegger and S. Schmid for technical assistance, S. Kreft for experimental advice and M. Collart for providing Caf1 antiserum. This work was supported by fellowships of the Konstanz Research School Chemical Biology to S.P., M.K., J.R. and A.S. and by research grants from the German Science Foundation (DFG; SFB969) and from Human Frontier in Science to E.D.

Author contributions

SP conceived the study, designed the experiments, performed the research, analysed the data and prepared the manuscript. JR performed the experiments, contributed to experimental design and analysed the data. MK performed the experiments, contributed to experimental design and analysed the data. AS performed the experiments and analysed the data. MB performed the experiments. TF analysed mass spectrometry data. ED directed the study, contributed to experimental design, data analysis and manuscript preparation and submitted the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Supplementary Figure S1

Supplementary Figure S2

Supplementary Figure S3

Supplementary Figure S4

Supplementary Figure S5

Supplementary Figure S6

Supplementary Figure S7

Supplementary Figure S8

Supplementary Table S1

Supplementary Legends, Materials and Methods

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 1

Source Data for Figure 2

Source Data for Figure 3

Source Data for Figure 4

Source Data for Figure 5

Source Data for Figure 6

Source Data for Figure 7

Source Data for Figure 8

References

- Amberg DC, Burke D, Strathern JN Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Course Manual. 2005 edn. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arava Y, Wang Y, Storey JD, Liu CL, Brown PO, Herschlag D. Genome-wide analysis of mRNA translation profiles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3889–3894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0635171100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashe MP, De Long SK, Sachs AB. Glucose depletion rapidly inhibits translation initiation in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:833–848. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.3.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Salvadore C, Chiang YC, Collart MA, Liu HY, Denis CL. The CCR4 and CAF1 proteins of the CCR4 NOT complex are physically and functionally separated from NOT2, NOT4, and NOT5. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6642–6651. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basquin J, Roudko VV, Rode M, Basquin C, Seraphin B, Conti E. Architecture of the nuclease module of the yeast Ccr4 not complex: the Not1-Caf1-Ccr4 interaction. Mol Cell. 2012;48:207–218. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson MH, Joazeiro CA. Role of a ribosome-associated E3 ubiquitin ligase in protein quality control. Nature. 2010;467:470–473. doi: 10.1038/nature09371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann CB, Davies A, Cost GJ, Caputo E, Li J, Hieter P, Boeke JD. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast. 1998;14:115–132. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980130)14:2<115::AID-YEA204>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandman O, Stewart-Ornstein J, Wong D, Larson A, Williams CC, Li GW, Zhou S, King D, Shen PS, Weibezahn J, Dunn JG, Rouskin S, Inada T, Frost A, Weissman JS. A ribosome-bound quality control complex triggers degradation of nascent peptides and signals translation stress. Cell. 2012;151:1042–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JE, Huntzinger E, Fauser M, Izaurralde E. GW182 proteins directly recruit cytoplasmic deadenylase complexes to miRNA targets. Mol Cell. 2011;44:120–133. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charneski CA, Hurst LD. Positively charged residues are the major determinants of ribosomal velocity. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chekulaeva M, Mathys H, Zipprich JT, Attig J, Colic M, Parker R, Filipowicz W. miRNA repression involves GW182-mediated recruitment of CCR4-NOT through conserved W-containing motifs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1218–1226. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Rappsilber J, Chiang YC, Russell P, Mann M, Denis CL. Purification and characterization of the 1.0 MDa CCR4-NOT complex identifies two novel components of the complex. J Mol Biol. 2001;314:683–694. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Sharma MR, Shi X, Agrawal RK, Joseph S. Fragile X mental retardation protein regulates translation by binding directly to the ribosome. Mol Cell. 2014a;54:407–417. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Boland A, Kuzuoglu-Ozturk D, Bawankar P, Loh B, Chang CT, Weichenrieder O, Izaurralde E. A DDX6-CNOT1 complex and W-binding pockets in CNOT9 reveal direct links between miRNA target recognition and silencing. Mol Cell. 2014b;54:737–750. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coller JM, Tucker M, Sheth U, Valencia-Sanchez MA, Parker R. The DEAD box helicase, Dhh1p, functions in mRNA decapping and interacts with both the decapping and deadenylase complexes. RNA. 2001;7:1717–1727. doi: 10.1017/s135583820101994x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coller J, Parker R. General translational repression by activators of mRNA decapping. Cell. 2005;122:875–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coller J. Methods to determine mRNA half-life in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 2008;448:267–284. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02614-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke A, Prigge A, Wickens M. Translational repression by deadenylases. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:28506–28513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.150763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JC, Van Driesche SJ, Zhang C, Hung KY, Mele A, Fraser CE, Stone EF, Chen C, Fak JJ, Chi SW, Licatalosi DD, Richter JD, Darnell RB. FMRP stalls ribosomal translocation on mRNAs linked to synaptic function and autism. Cell. 2011;146:247–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova LN, Kuroha K, Tatematsu T, Inada T. Nascent peptide-dependent translation arrest leads to Not4p-mediated protein degradation by the proteasome. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:10343–10352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808840200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly ML, Luke G, Mehrotra A, Li X, Hughes LE, Gani D, Ryan MD. Analysis of the aphthovirus 2A/2B polyprotein ‘cleavage’ mechanism indicates not a proteolytic reaction, but a novel translational effect: a putative ribosomal ‘skip’. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:1013–1025. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-5-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doronina VA, Wu C, de Felipe P, Sachs MS, Ryan MD, Brown JD. Site-specific release of nascent chains from ribosomes at a sense codon. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4227–4239. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00421-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond SP, Hildyard J, Firczuk H, Reamtong O, Li N, Kannambath S, Claydon AJ, Beynon RJ, Eyers CE, McCarthy JE. Diauxic shift-dependent relocalization of decapping activators Dhh1 and Pat1 to polysomal complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:7764–7774. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duttler S, Pechmann S, Frydman J. Principles of cotranslational ubiquitination and quality control at the ribosome. Mol Cell. 2013;50:379–393. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian MR, Cieplak MK, Frank F, Morita M, Green J, Srikumar T, Nagar B, Yamamoto T, Raught B, Duchaine TF, Sonenberg N. miRNA-mediated deadenylation is orchestrated by GW182 through two conserved motifs that interact with CCR4-NOT. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1211–1217. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstrohm AC, Hook BA, Seay DJ, Wickens M. PUF proteins bind Pop2p to regulate messenger RNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:533–539. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graille M, Seraphin B. Surveillance pathways rescuing eukaryotic ribosomes lost in translation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:727–735. doi: 10.1038/nrm3457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulshan K, Thommandru B, Moye-Rowley WS. Proteolytic degradation of the Yap1 transcription factor is regulated by subcellular localization and the E3 ubiquitin ligase Not4. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:26796–26805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.384719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie C, Fink GR. Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular and Cell Biology. Amsterdam: Academic Press; 2002. ; Boston; London: [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez E, Shin BS, Woolstenhulme CJ, Kim JR, Saini P, Buskirk AR, Dever TE. eIF5A promotes translation of polyproline motifs. Mol Cell. 2013;51:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halter D, Collart MA, Panasenko OO. The Not4 E3 ligase and CCR4 deadenylase play distinct roles in protein quality control. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e86218. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata H, Mitsui H, Liu H, Bai Y, Denis CL, Shimizu Y, Sakai A. Dhh1p, a putative RNA helicase, associates with the general transcription factors Pop2p and Ccr4p from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1998;148:571–579. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.2.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth J, Alver RC, Anderson M, Bielinsky AK. Ubc4 and Not4 regulate steady-state levels of DNA polymerase-alpha to promote efficient and accurate DNA replication. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:3205–3219. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-06-0452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes LE, Campbell SG, De Long SK, Sachs AB, Ashe MP. Loss of translational control in yeast compromised for the major mRNA decay pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2998–3010. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.2998-3010.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Sweet TJ, Chamnongpol S, Baker KE, Coller J. Co-translational mRNA decay in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2009;461:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature08265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Petzold C, Coller J, Baker KE. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decapping occurs on polyribosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:244–247. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]