Abstract

Background

Phencyclidine (PCP) is a synthetic compound derived from piperidine and used as an anesthetic and hallucinogenic. Little has been recently published regarding the clinical presentation of PCP intoxication. PCP use as a recreational drug is resurging.

Objective

Our objective was to describe clinical findings in patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) under the influence of PCP.

Methods

This was a case series study conducted at a tertiary care center with an annual census of 100,000 patients/year. Emergency physicians, residents, physician assistants, and research assistants identified patients with possible PCP intoxication. Self-reported PCP use, report by bystanders or Emergency Medical Services (EMS) staff, was used in this process. A structured data collection form was completed, documenting both clinical and behavioral events observed by the treating team during the ED visit.

Results

We collected data on 219 patients; 184 were analyzed; two patients were excluded secondary to incomplete data. The mean age of patients was 32.5 years (±7 years) with 65.2 % being males. PCP use was self-reported by 60.3 % of patients. Of the 184 patients, 153 (83.1 %) received a urine drug screen (UDS); 152 (98.7 %) were positive for PCP. On arrival, 78.3 % of patients were awake and alert, and 51.6 % were oriented to self, time/date, and place. Mean physiological parameters were the following: heart rate 101.1 bpm (±24.3), RR 18.9 bpm (±3.4), BP 146.3 (±19.4)/86.3 (±14.0) mmHg, 36.9° C (±0.5), and pulse oximetry 98.2 % (±1.9). Clinical findings were the following: retrograde amnesia in 46 (25 %), horizontal nystagmus in 118 (64.1 %), vertical nystagmus in 90 (48.9 %), hypertension in 87 (47.3 %), and agitation in 71 (38.6 %). Concomitant use of at least one other substance was reported by 99 (53.8 %) patients. The mean length of stay in the ED for all subjects was 261.1 (±172.8) minutes. Final disposition for 152 (82.6 %) patients was to home. Of the 184 patients, 14 (7.6 %) required admission; 12 were referred to Crisis Response Center.

Conclusion

Patients with PCP intoxication tended to be young males. The prevalent clinical signs and symptoms were the following: retrograde amnesia, nystagmus, hypertension, and psychomotor agitation. Co-use of other substances was the norm. Most patients presenting to the ED with PCP intoxication do well and can be discharged home after a period of observation.

Keywords: Phencyclidine, Anesthetic, Hallucinogenic

Introduction

Phencyclidine (PCP) is a synthetic compound derived from piperidine with anesthetic and hallucinogenic properties. PCP use as a recreational drug is resurging. The 2011 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration reported 75,538 emergency department (ED) visits related to PCP use [1]. Further, the number of PCP-related ED visits has increased more than 50 % since 2004 [1]. The 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data showed that 6.1 million Americans, 12 years or older, reported using PCP in their lifetime [2]. The recent Monitoring the Future survey results suggest that use of PCP has reemerged in recent years after being forgotten for decades. This may be due to a phenomenon called “generational forgetting” [3]. Appearance of synthetic analogs of PCP and ketamine is also an emerging concern [4].

Review of the literature demonstrates that little has been published on clinical presentation of PCP intoxication in recent years. Researchers published extensively on PCP symptomatology in the 1970s and 1980s demonstrating that presenting symptoms of altered mental status, agitation, violent behavior, nystagmus, and hypertension were prominent findings. Co-use with other illicit drugs was also common [5–8]. Anecdotal evidence of recent increase in PCP-related ED admissions at our facility has made revisiting this topic of interest to us. There is clear evidence that PCP use is on the rise nationally as well [2].

Objectives

The objective of this study was to review and update clinicians on the pattern of acute toxicity associated with PCP use.

Methods

This was a case series study conducted in the ED of a tertiary care center with an annual census of approximately 100,000 patients per year. Emergency medicine-trained physicians and residents completed a structured data collection form on both clinical and behavioral events in identified patients presenting to the ED with presumed PCP ingestion. The study was purely observational, and no study-related interventions were performed. Data was gathered without unique identifiers from June of 2011 to March of 2013. This study was approved by our hospital institutional review board. The study was determined to be IRB exempt.

Subjects included for analysis were patients over 18 years of age presenting to the ED with a presumed PCP intoxication. Excluded patients were those who were under 18 years old, denied PCP use with a negative or uncollected urine drug screen (UDS). Subjects identified as possible PCP intoxications had a standardized survey form completed by the physician in charge of their care.

Data gathered included demographics, PCP use, route, concomitant use of other drugs, presenting symptoms, vital signs, physical findings, UDS results, and hematology and blood chemistry. The patients’ duration of stay in the ED and their disposition from the ED to home, hospital admission, or transfer to a psychiatric Crisis Response Center (CRC) were recorded as well.

No statistical methods were used to calculate sample size since there is no intervention being measured. A priori, we decided to capture data on 200 patients. The incidences of all parameters mentioned above were calculated. Mean, standard deviation, median, interquartile range (IQR), and minimum and maximum values were calculated as when needed.

Results

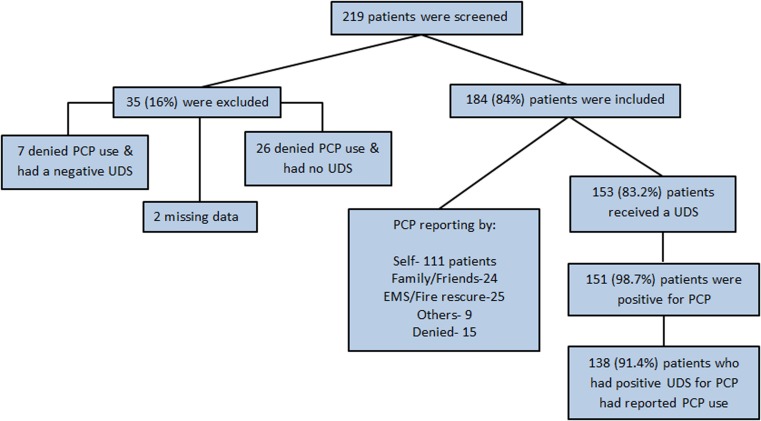

We were able to screen 219 cases in a period of 21 months. Out of all screened patients, we were able to collect data on 184 subjects. Of the 35 excluded, two did not have a completed data; seven denied PCP use, and their UDS was negative for PCP; 26 denied PCP use and had no UDS performed (Fig. 1). The mean age of the study population was 32.5 ± 7.0 years (range 20–53 years). Males accounted for 65.2 % of the population. The results of vital signs and clinical findings are described in Tables 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Collected data of 219 screened patients

Table 1.

Vital signs

| Parameter | Number | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (bpm) | 162 | 101.0 (24.3) | 98 (84.8–115) |

| Respiratory rate (RR) | 155 | 18.9 (3.4) | 18 (16–20) |

| Systolic pressure (mm Hg) | 164 | 146.3 (19.4) | 145 (134.3–161.8) |

| Diastolic pressure (mm Hg) | 164 | 87.3 (14.0) | 87 (77–98) |

| Temperature (°C) | 148 | 36.9 (0.5) | 36.9 (36.7–37.2) |

| Pulse oximetry on room air (%) | 171 | 98.2 (1.9) | 98 (97–100) |

bpm beats per min, mm Hg millimeters of mercury

Table 2.

Clinical findings

| Parameter | All cases (N = 184) | Lone PCP positive on UDS (N = 61) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.6 |

| Abnormal proprioception | 10 | 5.4 | 4 | 6.6 |

| Abnormal stereognosis | 2 | 1.1 | 1 | 1.6 |

| Amnesia (retrograde) | 46 | 25 | 18 | 29.5 |

| Ataxia | 16 | 8.7 | 3 | 4.9 |

| Auditory hallucinations | 3 | 1.6 | 1 | 1.6 |

| Decreased pain perception | 20 | 10.9 | 5 | 8.2 |

| Delusions | 14 | 7.6 | 6 | 9.8 |

| Diaphoresis | 19 | 10.3 | 5 | 8.2 |

| Diplopia | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.6 |

| Dissociation | 6 | 3.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Dysphoria | 18 | 9.8 | 6 | 9.8 |

| Hypersalivation | 7 | 3.8 | 4 | 6.6 |

| Hypertension | 87 | 47.3 | 32 | 52.5 |

| Miosis | 10 | 5.4 | 2 | 3.3 |

| Mydriasis | 11 | 6 | 3 | 3.3 |

| Nystagmus, horizontal | 118 | 64.1 | 38 | 62.3 |

| Nystagmus, rotatory | 3 | 2.6 | 2 | 3.2 |

| Nystagmus, vertical | 90 | 48.9 | 30 | 49.2 |

| Paranoia | 32 | 17.4 | 8 | 13.1 |

| Physically abusive | 25 | 13.6 | 10 | 16.4 |

| Psychomotor agitation | 71 | 38.6 | 24 | 39.3 |

| Tachycardia | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Verbally abusive | 19 | 10.3 | 5 | 8.2 |

| Visual hallucinations | 7 | 3.8 | 3 | 4.9 |

Route of administration was reported to be smoking in 154 patients (83.2 %); one patient reported snorting, and data on route was not available for 29 (15.7 %) cases. Co-use of at least one other substance was reported by 99 (53.8 %) patients; 23 (12.5 %) reported no co-ingestion; for 62 (33.7 %) cases, this data was missing. Of the 184 cases, 18 (9.8 %) reported co-ingestion of at least two substances in addition to PCP and five (2.7 %) reported using at least three substances in addition to PCP. All concomitant substances used and a comparison of reported use versus the UDS results are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Concomitant substances and comparison of reported vs. UDS results

| Drug | Reported use (N = 184) | UDS positive (N = 153) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | |

| PCP | 169 | 91.8 | 151 | 98.7 |

| Alcohol | 37 | 20.1 | Not done | – |

| Amphetamine | 2 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Barbiturates | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.3 |

| Benzodiazepine | 13 | 7.1 | 39 | 25.5 |

| Cocaine | 10 | 5.4 | 14 | 9.1 |

| Heroin | 2 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Marijuana | 47 | 25.5 | 63 | 41.2 |

| Opiates | 2 | 1.1 | 19 | 12.4 |

Clinical findings varied greatly from subject to subject, and most were temporary. Patients in the emergency department displayed varying degrees of mentation. We attempted to collect data on time of ingestion in order to correlate with degree of symptoms but were only successful in 17 cases out of the 184 (9.2 %). Due to the very small number of cases, this was not further analyzed. Out of the 184 cases, 144 (78.3 %) were alert at presentation. Orientation was fully intact in 95 (51.6 %) of patients. Retrograde amnesia was reported in 46 patients (25 %); out of these 46 cases, 11 patients had a positive UDS for benzodiazepine. Most patients had temporary minor vital sign abnormalities deemed clinically insignificant. Out of all the patients enrolled, 14 (7.6 %) required supplemental oxygen.

Urine drug screen was performed on 153 patients out of the 184 patients included. PCP was positive in 151 out of 184 (82.1 %). UDS result for all concomitant substances is described in Table 3.

The mean length of stay in the ED for all subjects was 261.1 (±172.8) min. The median length was 211 min (IQR 150–328 min). Final disposition for 152 (82.6 %) patients was to home. Of the 184 patients, 14 (7.6 %) required admission, 12 were referred to CRC, and final disposition for six could not be confirmed. Of the 14 admitted patients, four (28.6 %) were admitted to the general medical floor; four (28.6 %) to observation unit; one (7.1 %) to the step down unit, telemetry, intensive care, and antenatal unit, respectively. The step down unit at our institution is a medical unit that manages patients whose clinical condition is of intermediate acuity between general medical floor and the intensive care unit. This unit has higher trained nurses and a lower nursing ratio.

Discussion

PCP is a hallucinogenic and anesthetic drug invented in 1926. Until 1970s, PCP was used as an anesthetic drug for patients requiring dissociative anesthesia. After the medicinal use, PCP was discontinued due to its hallucinogenic side effects; it emerged as a recreational drug in 1970s. Yaqo et al. in 1981 described blood sample testing of 145 consecutive patients presenting during a 48-h period to psychiatric emergency in Los Angeles area. Out of those, 43 % patients tested positive for PCP highlighting high incidence of PCP abuse at that time. The presenting symptoms although were described only as mania, depression, and psychosis. In the same year, McCarron et al. described most common clinical features of PCP intoxication in 1000 patients [6]. According to them the most common presenting symptoms were nystagmus and hypertension in 57 % of the patient followed by violence (35 %) and agitation in 34 % of the patients.

These findings are comparable to the presenting symptoms in our patients with horizontal nystagmus present in 64.1 % of patients followed by hypertension (47.3 %), vertical nystagmus (48.9 %), agitation (38.6 %), and retrograde amnesia (25 %). Half of the patients were fully oriented (51.6 %), and more than three quarters (78.3 %) were alert at the time of presentation. None of our patients experienced serious vital sign abnormalities as compared to 0.3 % of cardiac arrest and apnea in 2.8 % of patients described by McCarron et al [6]. Our population consisted mostly of young men. The prevalent clinical signs and symptoms were the following: retrograde amnesia, nystagmus, hypertension, and psychomotor agitation. Majority of the patients had minimal alteration in vital signs and were discharged once their symptoms resolved with only 7.6 % requiring admission.

This study has a number of limitations. The most important of these is that the presence of PCP in urine samples was measured by a urine immunoassay test. This was not confirmed by any other analytical technique; therefore, it is possible that the initial positive immunoassay result may have been due to cross-reaction with one or more prescribed, over the counter, or recreational drug(s). In addition, 25 % of our patients had retrograde amnesia and the frequency of UDS positivity for benzodiazepines was 25.5 %; it is possible that some or all of this amnesia was due to the benzodiazepines detected rather than the PCP. Several compounds may interfere with the Multigent Assay (Abbot Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA) used to test for PCP [9].

Conclusion

Patients presenting to the emergency department after PCP ingestion can have resource intensive visits. Most patients have poly-pharmacy ingestions when presenting to the ED. Length of stay for patients presenting to the ED after PCP use is usually a couple of hours. Most of the clinical manifestations in this population are temporary, and majority of the patients are discharged home. This study provides current day ED providers with an overview of the most common presenting clinical and behavioral signs and symptoms.

References

- 1.Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.htm#high3.

- 2.Drug enforcement administration office of diversion control drug & chemical evaluation section on PCP Jan 2013.

- 3.Monitoring the Future: National survey results on drug use 2013 overview http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2013.pdf.

- 4.Pourmand A, Armstrong P, Mazer-Amirshahi M, Shokoohi H. The evolving high: new designer drugs of abuse. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.McCarron MM, Schulze BW, Thompson GA, Conder MC, Goetz WA. Acute phencyclidine intoxication: clinical patterns, complications, and treatment. Ann Emerg Med. 1981;10(6):290–7. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(81)80118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarron MM, Schulze BW, Thompson GA, Conder MC, Goetz WA. Acute phencyclidine intoxication: incidence of clinical findings in 1,000 cases. Ann Emerg Med. 1981;10(5):237–42. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(81)80047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barton CH, Sterling ML, Vaziri ND. Phencyclidine intoxication: clinical experience in 27 cases confirmed by urine assay. Ann Emerg Med. 1981;10(5):243–6. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(81)80048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis BL. The PCP epidemic: a critical review. Int J Addict. 1982;17(7):1137–55. doi: 10.3109/10826088209056346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Multigent Urine Drug Assay: phencyclidene package insert for Architect/Aeroset system developed by Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA.