Abstract

Introduction

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Although gender has not been included in prognostic systems, male gender has been found as a bad prognostic indicator in Hodgkin lymphoma, follicular lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. The relationship between gender and prognosis is not clear in patients with DLBCL treated with rituximab-containing regimens. The aim of this meta-analysis is to determine the prognostic/predictive role of gender in patients with DLBCL treated with rituximab-containing regimens.

Material and methods

We systematically searched for studies investigating the relationships between gender and prognosis in DLBCL treated with rituximab-containing regimens. After careful review, survival data were extracted from eligible studies. A meta-analysis was performed to generate combined hazard ratios for overall survival, disease-free survival (DFS) and event-free survival (EFS).

Results

A total of 5635 patients from 20 studies were included in the analysis. Our results showed that male gender was associated with poor prognosis in terms of overall survival (OS) (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.155; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.037–1.286; p < 0.009). The pooled hazard ratio for DFS and EFS showed that male gender was not statistically significant (HR = 1.219; 95% CI: 0.782–1.899; p = 0.382, HR = 0.809; 95% CI: 0.577–1.133; p = 0.217).

Conclusions

The present meta-analysis indicated male gender to be associated with a poor prognosis in patients with DLBCL treated with rituximab-containing regimens.

Keywords: diffuse large B cell lymphoma, gender, prognosis

Introduction

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Thirty-one percent of all NHLs and 80% of aggressive lymphomas are DLBCL, which is generally seen in the 6th and 7th decades of life [1, 2]. Prognostic factors in DLBCL are age, performance score, stage, proliferation fraction and gene expression profiles [3, 4]. Today, the International Prognostic Index (IPI) and age-adjusted International Prognostic Index (aaIPI) are the most important scores used in daily practice to determine the prognosis and treatment strategies. The IPI scoring system includes age, performance status, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, stage and extranodal involvement; the aaIPI includes stage, LDH, performance status and age older than 60 years.

In the last decade, the standard of care in patients with DLBCL has been the addition of anti-CD20 antibody-rituximab to classic cytotoxic chemotherapy. More sophisticated methods and drugs targeting oncogenic pathways and gene expression profiles have been used to predict the prognosis and response to therapy in recent years [5–7]. Although gender has not been included in prognostic systems, male gender has been found to be a bad prognostic indicator in Hodgkin lymphoma, follicular lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia [8–10]. However, the prognostic significance of gender has not been shown in all studies [11, 12].

The aim of this meta-analysis was to determine the prognostic/predictive role of gender in patients with DLBCL treated with rituximab-containing regimens.

Material and methods

Research strategy

A computer-based literature search using the PubMed/Medline database was performed by two independent researchers (VK, OD). The initial PubMed search using the combined term (rituximab) and (lymphoma, large B-cell, diffuse) resulted in 1520 returns up to August 7, 2013. Only English language and human studies were included in this analysis. Full text articles of all selected studies were retrieved. If a paper was selected for inclusion, the bibliographic references were carefully investigated to look for additional studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Prospective and retrospective randomized controlled studies involved patients older than 18 years who were treated according to rituximab-containing regimens. Case reports and series, letters, commentaries, lymphoma series including those other than DLBCLs and studies not containing an effect size for survival according to gender were not included.

Selection of studies

Two independent reviewers decided which studies to include (MY, SP). The abstracts of all papers found to be appropriate for meta-analysis were read. The full texts of the candidate papers for this analysis were evaluated. Patients with DLBCL treated with rituximab-containing regimens were included in this analysis. If the patients had been included in different studies by the same author, the higher quality study was considered for this meta-analysis.

Assessment of study quality

The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale was used for the evaluation of non-randomized controlled studies and the Jadad scoring system was used for the evaluation of randomized controlled studies by two independent reviewers (MY, VK). The Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale is used to determine the choice of patient population, comparability, follow-up and results of the studies. For these criteria studies are scored with stars between 0 and 9. A score of nine stars indicates the highest quality [13]. The Jadad scoring system is based on 5 stars [14]. Discrepancies between the authors after evaluations were re-evaluated and consensus was reached for all data.

Data extraction

For studies evaluating gender and rituximab-containing regimens in cases of NHL treated with rituximab-containing regimens, the following variables were extracted: essential data about study, author, publication year, country of study, design of the study, demographic data, gender distribution, treatment schedules, stage, and effect size of gender on the overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS) and event-free survival (EFS).

Statistical analysis

The primary aim of this study was to analyze the effect of gender on the OS in patients with DLBCL treated with rituximab-containing regimens. Disease-free survival and EFS were also analyzed. Hazard ratio (HR) was calculated with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Hr > 1 and not including 95% coincidence interval 1 were considered as significant. If there was no HR, summary statistics were used. Homogeneity was evaluated using the χ2-based test of homogeneity and inconsistency index. A p-value < 0.10 for χ2 or I 2 > 50% was accepted as heterogeneity. Results were given using a fixed model. A p-value for summary HR of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Publication bias was examined using Egger's regression intercept, Begg-Mazumdar rank correlation analysis, and a visual inspection of a funnel plot [15, 16]. Statistical analyses were performed using Comprehensive Metaanalysis V 2.0 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ).

Results

Study eligibility

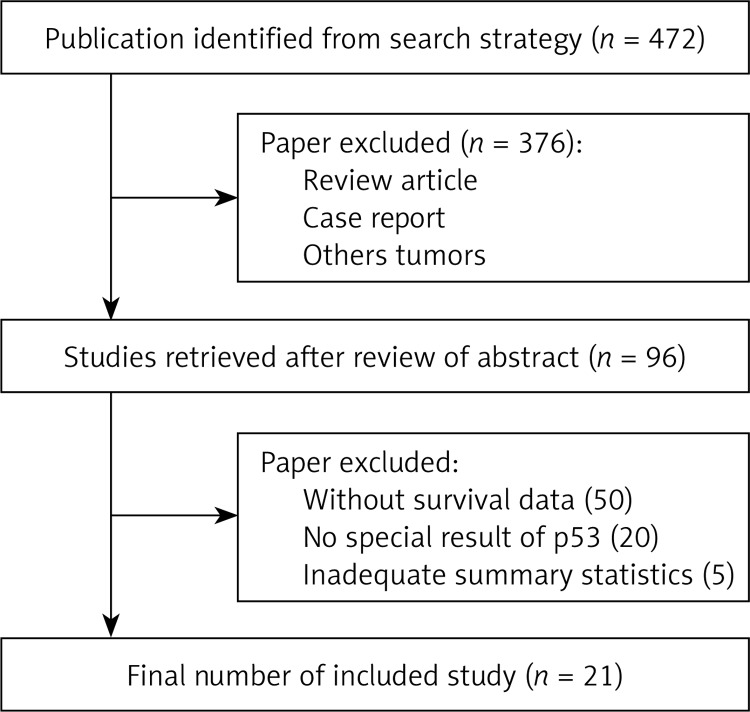

The computer-based literature search using PubMed/Medline resulted in 1520 articles. Evaluation of the title and abstract of these articles revealed 377 case reports, 188 reviews, 32 letters, 34 comments, 63 non-English language studies, 13 pediatric studies, 11 cell studies, and 3 animal studies, and these were excluded from further analysis, leaving 799 papers. Of these 11 were cases series, 69 had included other lymphoma subtypes, 120 papers had not included rituximab-containing regimens, 3 did not report subgroup survival analyses, and 564 did not include the data effect size for gender. All these papers were excluded, leaving 26 papers. However, among these 26 papers, there were no effect size data in cases receiving rituximab according to gender in 5 papers and these papers were thus excluded from further analysis. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of articles included in this meta-analysis. Ultimately, 20 studies were included in this meta-analysis (Table I [11, 17–35]).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection process

Table I.

Summary of trials included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Country | Study design | Total number of patients | Male | Female | Median age | Stage | Median follow-up time [months] | Treatment arms | HR (OS) | Value of p (OS) | HR (DFS) | Value of p (DFS) | HR (EFS) | Value of p (EFS) | Study quality score | Conclusion | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kang, 2013 | Korea | Retrospective | 567 | 288 | 231 | 3–4 | 33.2 | CHOP-R | 0.849 | 0.354 | 0.866 | 0.497 | 7 | NS | 14 | |||

| Lanic, 2013 | France | Retrospective | 82 | 36 | 46 | 80.2 | 1–4 | 32.8 | CHOP-R | 0.62 | 0.1 | 0.63 | 0.1 | 7 | NS | 15 | ||

| Koh, 2013 | Korea | Retrospective | 120 | 75 | 45 | 59.5 | 1–4 | NR | CHOP-R | 1.621 | 0.209 | 6 | NS | 17 | ||||

| Zho, 2013 | China | Retrospective | 227 | 128 | 99 | 53.2 | 1–4 | NR | CHOP-R | 0.657 | 0.14 | 6 | NS | 18 | ||||

| Aoki, 2013 | Japan | Retrospective | 109 | 61 | 48 | NR | 1–4 | 27 | CHOP-R | 2.1 | 0.057 | 7 | NS | 19 | ||||

| Tomita, 2013 | Japan | Retrospective | 190 | 111 | 79 | 63 | 1–2 | 52 | CHOP-R | 0.9 | 0.36 | 0.7 | 0.41 | 8 | NS | 20 | ||

| Yri, 2013 | Norway | Retrospective | 340 | 192 | 148 | 60 | 1–4 | 66 | CHOP-R | 1.09 | 0.7 | 6 | NS | 21 | ||||

| Castillo, 2013 Western | Multicenter | Retrospective | 257 | 150 | 107 | 63 | 1–4 | 36 | CHOP-R | 1.42 | 0.1 | 7 | NS | 22 | ||||

| Castillo, 2013 Asian | Multicenter | Retrospective | 455 | 247 | 248 | 64 | 1–4 | 36 | CHOP-R | 1.09 | 0.61 | 7 | NS | 22 | ||||

| Huang, 2012 | China | Retrospective | 97 | 60 | 37 | 59 | 1–4 | 56 | CHOP-R | 0.55 | 0.158 | 0.562 | 0.168 | 7 | NS | 23 | ||

| Flowers, 2013 | USA | Retrospective | 342 | NR | NR | NR | 1–4 | 35 | CHOP-R | 0.97 | 5 | NS | 24 | |||||

| Carella, 2013 | Italy, Brazil | Retrospective | 1793 | 943 | 850 | 62 | 1–4 | 36 | CHOP-R | 1.52 | 0.001 | 8 | S | 25 | ||||

| Pregno, 2012 | Italy | Prospective | 88 | 41 | 47 | 55 | 1–4 | 26.2 | CHOP-R | NR | 1.06 | 0.895 | 5 | NS | 26 | |||

| Merli, 2012 | Italy | Prospective | 110 | 55 | 55 | 71 | 1–4 | 42 | CHOP-R/miniCEOP | 0.96 | NR | 5 | NS | 27 | ||||

| Tanaka, 2012 | Japan | Retrospective | 95 | 50 | 45 | 68 | 1–4 | 34.5 | CHOP-R | 3.636 | 0.058 | 6 | NS | 28 | ||||

| Aoki, 2012 | Japan | Retrospective | 59 | 36 | 23 | 71 | 1–4 | 70 | CHOP-R/CVP-R | NR | 0.94 | 0.912 | 6 | NS | 29 | |||

| Riihijarvi, 2010 | Sweden | Retrospective | 217 | 126 | 91 | 61 | 1–4 | 49 | CHOP-R/CHOEP-R | NR | 0.51 | 0.014 | 6 | S | 11 | |||

| Yoo, 2010 | Korea | Retrospective | 126 | 64 | 52 | 57 | 3–4 | 22.4 | CHOP-R | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.13 | 0.76 | 7 | NS | 30 | ||

| Ennishi, 2010 | Japan | Retrospective | 131 | 79 | 52 | 68 | 1–4 | 32 | CHOP-R/CHOEP-R | 1.44 | NR | 1.47 | 6 | NS | 31 | |||

| Terada, 2009 | Japan | Retrospective | 100 | 55 | 45 | 60 | 1–4 | 21.2 | CHOP-R | 2.6 | 0.14 | 8 | NS | 32 | ||||

| Chae, 2010 | Korea | Retrospective | 90 | 51 | 39 | 58 | 1–4 | 27.4 | CHOP-R | NR | 0.15 | 0.179 | 6 | NS | 33 |

Quality of papers included in this meta-analysis

Two of 20 studies included in this analysis were prospective and 18 were retrospective. The quality of retrospective studies was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. In this scale 1–3 is considered as a low quality study, 4–6 as an intermediate quality study and 7–9 as a high quality study. The median Jadad score was 6 and 5 for retrospective and prospective studies, respectively.

Patients

The total number of patients included in this meta-analysis was 5635: 2879 (54.4%) men and 2414 (45.6%) women, giving a female/male ratio of 0.83. (In one study there were 346 patients in the group treated with rituximab, but there was no information about gender.) The median age was 62.9 and rituximab had been used as first-line therapy.

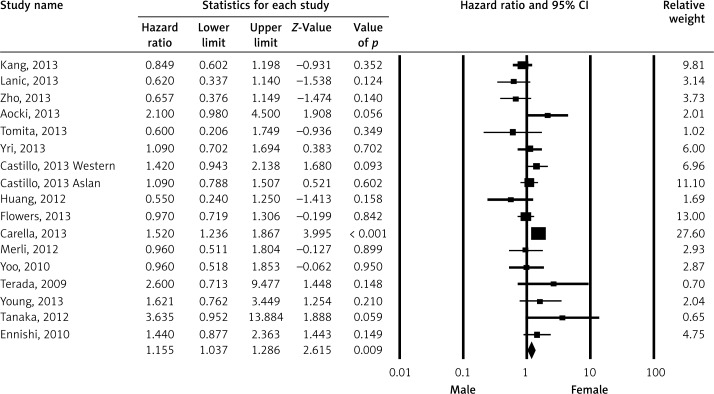

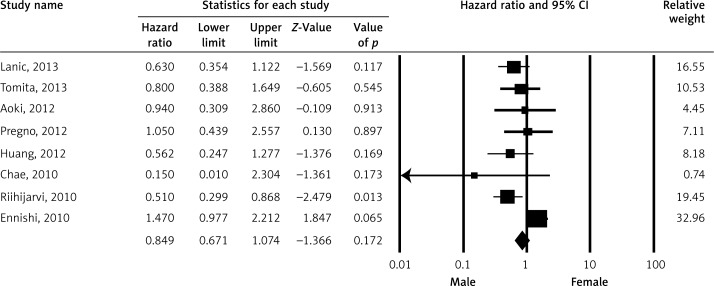

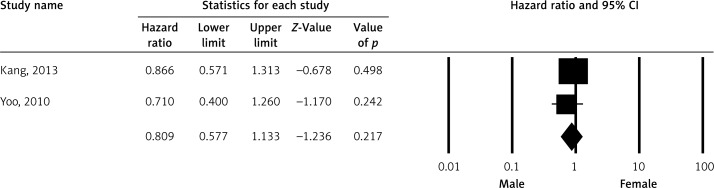

Overall survival, disease-free survival, event-free survival

Pooled HR for OS was evaluated in 16 studies and male gender was found to be associated with OS (HR = 1.155; 95% CI: 1.037–1.286; p < 0.009) (Figure 2). The association between gender and progression-free survival (PFS) was evaluated in eight studies and there was no statistically significant association (HR = 0.849; 95% CI: 0.671–1.074; p = 0.171) (Figure 3). Event-free survival was evaluated in two studies and there was no association between gender and EFS (HR = 0.809; 95% CI: 0.577–1.133; p = 0.217) (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of overall survival among patients receiving rituximab according to gender

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of disease-free survival among patients receiving rituximab according to gender

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of event-free survival among patients receiving rituximab according to gender

Publication bias

There was no publication bias for OS (Begg's test, p = 0.564; Egger test, p = 0.557). The funnel plot did not show publication bias for OS (Figure 5 A). There was no publication bias for PFS (Begg's test, p = 0.286; Egger test, p = 0.254). The funnel plot was symmetric and did not show publication bias for OS (Figure 5 B). Publication bias could not be determined for EFS because only two studies were evaluated.

Figure 5.

Publication bias determination using funnel plot for (A) overall survival and (B) disease-free survival

Discussion

Male gender has been found to be a bad prognostic indicator for OS in cases treated with rituximab-containing regimens in some studies [17, 18]. An OS advantage has been shown in patients with DLBCL treated with rituximab-containing regimens for every age and risk group [36, 37].

Immunochemotherapy is the standard of care in patients with DLBCL; however, variable responses have been documented. This means that more sensitive prognostic and/or predictive factors are required. Although it has not been evaluated in all studies, male gender has been found to be a prognostic factor at least in some studies [38]. The relationship between gender and prognosis has been considered in recent years. Although this analysis covers studies between 2002 and 2013, the majority of the studies in this meta-analysis were published in 2013. Male sex has been shown to be a bad prognostic indicator in patients with DLBCL treated with rituximab-containing regimens [11, 27].

Prognostic factors in 700 cases from eight centers in Asian and Western countries treated by R-CHOP were compared by Castillo et al. They found no difference for PFS and OS, but male sex was found to be a bad prognostic indicator in multivariate analysis of patients of Asian origin [24]. This point is important, and more studies from different countries will be required to evaluate racial differences.

The prognostic role of gender in DLBCL has been reported in only a limited number of papers. In one of these papers, Carella et al. investigated the prognostic role of gender in 1793 patients with DLBCL treated with a rituximab-containing regimen between 2001 and 2007. In this study gender was found to be a bad prognostic indicator and the HR was 1.52. A higher dose of rituximab in males was suggested by the authors [27].

Gender was also found to be an independent prognostic factor by Gisselbrecht et al. in relapsed/refractory DLBCL treated with rituximab maintenance after autologous stem cell transplantation [39].

Lower serum rituximab levels, shorter exposure times and worse outcome in men were observed in the RICOVER-60, RICOVERnoRTh and pegfilgrastim trials (R1, R2, R3), and the SEXIE-R-CHOP 14 trial has been planned and performed. In the last ASCO conference this study was presented and a significantly improved outcome in male patients was observed with higher rituximab doses (500 mg/m2 instead of 375 mg/m2) [40]. These results confirm the worse outcome with standard R-CHOP in men.

The mechanism underlying the different prognosis in men and women is not clear. Pharmacokinetic studies suggest that higher serum levels are associated with lower drug clearance in females [41]. Additionally, gender-associated gene polymorphisms may be a contributing factor in the higher response to immune-chemotherapy in females. GSTT1 deletion has been suggested as a causative factor for resistance to R-CHOP and also poor prognosis in male Korean patients [42].

In conclusion, OS was found to be better in female cases than males with DLBCL treated with immunochemotherapy in this meta-analysis. Higher doses of rituximab could be more useful in males; the ongoing SEXI-R-CHOP-14 study will help clarify this point.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Martelli M, Ferreri AJ, Agostinelli C, Di Rocco A, Pfreundschuh M, Pileri SA. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;87:146–71. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2008. WHO classification of tumors of haematopoietic and lymphoidt issues. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferreri AJ. How I treat primary CNS lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:510–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-321349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zucca E, Conconi A, Mughal TI, et al. Patterns of outcome and prognostic factors in primary large-cell lymphoma of the testis in a survey by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:20–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, et al. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403:503–11. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenwald A, Wright G, Chan WC, et al. The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large-B cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1937–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 2004;103:275–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasenclever D, Diehl V. A prognostic score for advanced Hodgkin's disease. International Prognostic Factors Projection Advanced Hodgkin’ s Disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1506–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Federico M, Vitolo U, Zinzani PL, et al. Prognosis of follicular lymphoma: a predictive model based on a retrospective analysis of 987 cases. Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi. Blood. 2000;95:783–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catovsky D, Fooks J, Richards S. Prognostic factors in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: the importance of age, sex and response to treatment in survival. A report from the MRC CLL 1 trial. MRC Working Party on Leukaemia in Adults. Br J Haematol. 1989;72:141–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1989.tb07674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riihijarvi S, Taskinen M, Jerkeman M, et al. Male gender is an adverse prognostic factor in B-cell lymphoma patients treated with immunochemotherapy. Eur J Haematol. 2011;86:124–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ngo L, Hee SW, Lim LC, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma: before and after the introduction of rituximab. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:462–9. doi: 10.1080/10428190701809156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells GA, Brodsky L, O'Connell D, et al. An evaluation of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale: an assessment tool for evaluating the quality of non-randomized studies; In: XI Cochrane Colloquium Barcelona: XI International Cochrane Colloquium Book of Abstracts; 2003. p. 26. Vol.O-63. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br Med J. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang BW, Moon JH, Chae YS, et al. Clinical outcome of rituximab-based therapy (RCHOP) in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients with bone marrow involvement. Cancer Res Treat. 2013;45:112–7. doi: 10.4143/crt.2013.45.2.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanic H, Kraut-Tauzia J, Modzelewski R, et al. Sarcopenia is an independent prognostic factor in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Leuk Lymph. 2014;55:817–23. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.816421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koh YW, Hwang HS, Jung SJ, et al. Receptor tyrosine kinases MET and RON as prognostic factors in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients receiving R-CHOP. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:1245–51. doi: 10.1111/cas.12215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou D, Xie WZ, Hu KY, et al. Prognostic values of various clinical factors and genetic subtypes for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients: a retrospective analysis of 227 cases. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:929–34. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.2.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aoki K, Takahashi T, Tabata S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of reduced-dose 21-day cycle rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone therapy for elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:2441–7. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.780654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomita N, Takasaki H, Miyashita K, et al. R-CHOP therapy alone in limited stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2013;161:383–8. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yri OE, Ekstrøm PO, Hilden V, et al. Influence of polymorphisms in genes encoding immunoregulatory proteins and metabolizing enzymes on susceptibility and outcome in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:2205–14. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.774392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castillo JJ, Sinclair N, Beltrán BE, et al. Similar outcomes in Asian and Western patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Leuk Res. 2013;37:386–91. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang Y, Ye S, Cao Y, et al. Outcome of R-CHOP or CHOP regimen for germinal center and nongerminal center subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of Chinese patients. Sci World J. 2012;2012:897178. doi: 10.1100/2012/897178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flowers CR, Shenoy PJ, Borate U, et al. Examining racial differences in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presentation and survival. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:268–76. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.708751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carella AM, de Souza CA, Luminari S, et al. Prognostic role of gender in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab containing regimens: a Fondazione Italiana Linfomi/Grupo de Estudos em Moléstias Onco-Hematológicas retrospective study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:53–7. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.691482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pregno P, Chiappella A, Bellò M, et al. Interim 18-FDG-PET/CT failed to predict the outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated at the diagnosis with rituximab-CHOP. Blood. 2012;119:2066–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-359943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merli F, Luminari S, Rossi G, et al. Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone and rituximab versus epirubicin, cyclophosphamide, vinblastine, prednisone and rituximab for the initial treatment of elderly „fit” patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the ANZINTER3 trial of the Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:581–8. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.621565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka T, Shimada K, Yamamoto K, et al. Retrospective analysis of primary gastric diffuse large B cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: a multicenter study of 95 patients in Japan. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:383–90. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1306-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aoki T, Nishiyama T, Imahashi N, Kitamura K. Lymphopenia following the completion of first-line therapy predicts early relapse in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:375–82. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoo C, Kim S, Sohn BS, et al. Modified number of extranodal involved sites as a prognosticator in R-CHOP-treated patients with disseminated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Korean J Intern Med. 2010;25:301–8. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2010.25.3.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ennishi D, Maeda Y, Niitsu N, et al. Hepatic toxicity and prognosis in hepatitis C virus-infected patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab-containing chemotherapy regimens: a Japanese multicenter analysis. Blood. 2010;116:5119–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-289231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terada Y, Nakamae H, Aimoto R, et al. Impact of relative dose intensity (RDI) in CHOP combined with rituximab (R-CHOP) on survival in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:116. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chae YS, Kim JG, Sohn SK, et al. Lymphotoxin alfa and receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 gene polymorphisms may correlate with prognosis in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;65:571–7. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfreundschuh M, Trumper L, Osterborg A, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:379–91. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70664-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasselblom S, Ridell B, Nilsson-Ehle H, et al. The impact of gender, age and patient selection on prognosis and outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma – a population-based study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:736–45. doi: 10.1080/10428190601187703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gisselbrecht C, Schmitz N, Mounier N, et al. Rituximab maintenance therapy after autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with relapsed CD20(+) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: final analysis of the collaborative trial in relapsed aggressive lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4462–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.9416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfreundschuh M, Held G, Zeynalova S, et al. German High-Grad Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL). Increased rituximab (R) doses and effect on risk of elderly male patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphomas: results from the SEXIE-R-CHOP-14 trial of the DSHNHL. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32 5s (suppl; abstr 8501) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pfreundschuh MM, Zeyanalova S. Male sex is associated with lower rituximab trough serum levels and evolves as a significant prognostic factor in elderly patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP: results from 4 prospective trials of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin-Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL) Blood. 2009;114:1431. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cho HJ, Eom HS, Kim HJ, Kim IS, Lee GW, Kong SY. Glutathione-S-transferase genotypes influence the risk of chemotherapy-related toxicities and prognosis in Korean patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;198:40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]