Abstract

Interventional endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) based on EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration has rapidly spread as a minimally invasive procedure. Especially in patients with failed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, EUS-guided biliary intervention is reported to be useful as salvage therapy. EUS-guided biliary interventions are carried out using three techniques: EUS-guided bilioenteric anastomosis, EUS-guided rendezvous procedure, and EUS-guided antegrade treatment. Although interventional EUS is not yet a standardized procedure, there have been recent advances in this field that address various biliary diseases. Here, we summarize the indications, techniques, clinical results of previous studies, and future perspectives.

Keywords: Endosonography-guided biliary intervention, Choledochoduodenostomy, Hepaticogastrostomy, Rendezvous procedure, Antegrade treatment

Core tip: Endoscopic-ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage (EUS-BD) is widely accepted as salvage therapy for transpapillary treatment. However, there are few data comparing the clinical efficacy of EUS-BD and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with regard to which is the treatment of choice. As EUS-BD is performed under direct visualization, it has the potential to replace ERCP. However, a prospective randomized study is necessary to confirm it.

INTRODUCTION

The endoscopic transpapillary approach based on the endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) technique has been a standard treatment for various biliary diseases, such as choledocholithiasis and biliary obstruction[1,2]. ERCP sometimes fails, however, for various reasons[3]. Recently, interventional endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) based on EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) has been developed as a salvage therapy for transpapillary treatment. In patients with failed ERCP, percutaneous or surgical interventions are mandatory but are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality[4-6]. Interventional EUS could manage these patients with minimal invasion. Although interventional EUS is not yet a standardized procedure, there have been recent advances in this field that address various biliary diseases.

EUS-GUIDED BILIARY INTERVENTION TECHNIQUES

EUS-guided biliary interventions are carried out using three techniques: EUS-guided bilioenteric anastomosis (EUS-BEA), EUS-guided rendezvous procedure (EUS-RV), and EUS-guided antegrade treatment (EUS-AT). EUS-guided biliary drainage is performed with the armamentarium available for EUS-FNA and ERCP-related procedures such as an EUS-FNA needle, a guidewire, and a biliary stent.

EUS-BEA

EUS-BEA is performed to create an artificial fistula between the intestine and the bile duct by placing a stent. One indication for this procedure is the palliation of obstructive jaundice in patients with malignant diseases who have failed biliary drainage by ERCP. The procedure is mainly divided into three methods according to the anatomical site of the fistula: EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy (EUS-CDS), EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy (EUS-HGS), and EUS-guided gallbladder drainage (EUS-GBD). In these cases, the echoendoscope is advanced into the upper gastrointestinal tract (stomach, duodenum and jejunum), after which, the biliary system (bile duct or gallbladder) is punctured by a needle. The guidewire is then advanced into the biliary system followed by dilation of the fistula. Finally, the stent is deployed between the biliary system and the gastrointestinal tract.

EUS-CDS is undertaken to create a fistula between the extrahepatic bile duct and the duodenal bulb (Figure 1). Since the first report in 2001 by Giovannini et al[7], EUS-CDS has been widely accepted as an effective alternative therapy for palliation of distal malignant biliary obstruction after failed ERCP (Table 1)[8-13], although it is impossible to perform EUS-CDS in patients with altered upper gastrointestinal tract anatomy. Because of the anatomical proximity of the viscera, EUS-CDS is not technically challenging. The technical success rate is reported to be 86%-100%. Artifon et al[14] reported that the clinical success and complication rates were similar for EUS-CDS and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) for patients in whom ERCP failed. Plastic stents were mainly placed in the early cases of EUS-CDS, whereas more recently self-expandable metallic stents (SEMSs) have played a major role. EUS-CDS is mainly indicated for patients with distal malignant biliary obstruction in whom ERCP has failed. However, the feasibility of EUS-CDS as the first-line treatment for distal malignant biliary obstruction was recently reported[12]. The complication rate was reported at 9%-23%. Biliary peritonitis and pneumoperitoneum were the most frequent complications. Others were stent migration, bleeding, and cholangitis. There are no standardized techniques for managing these complications, so it is important to be ready to handle any situation[15-19]. Recently, the feasibility of performing EUS-CDS with specialized stents has been reported[20-22]. Widespread use of sophisticated SEMSs for EUS-CDS could reduce the incidence of complications.

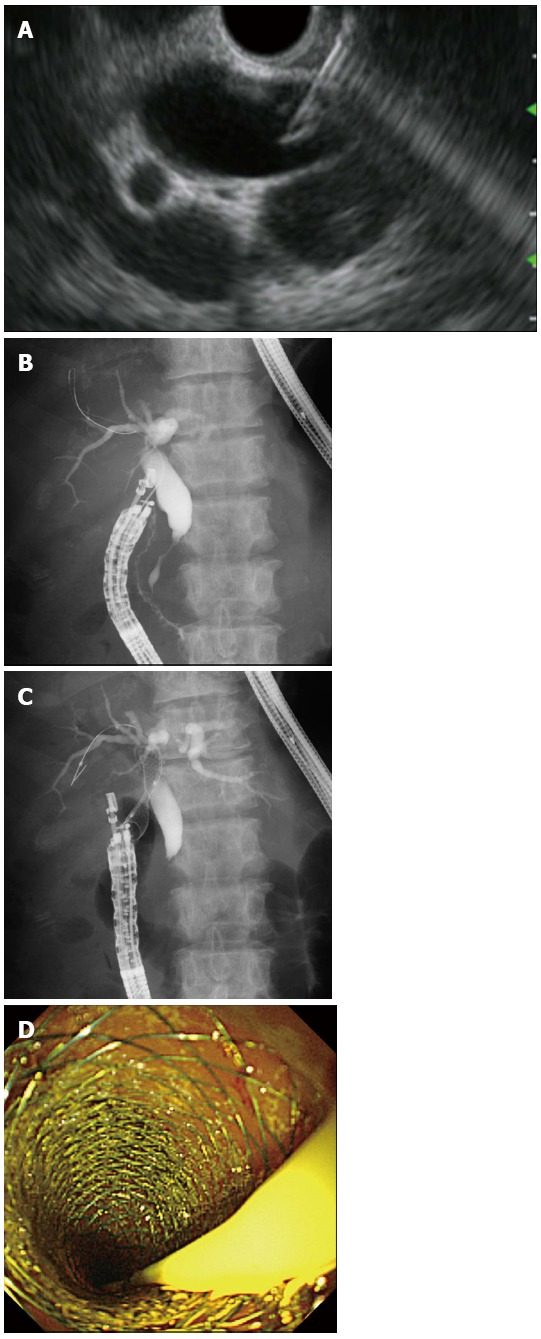

Figure 1.

Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided choledochoduodenostomy. A: Endoscopic ultrasonography showing that extrahepatic bile duct was punctured by the needle; B: Guidewire was advanced through the needle into the right liver lobe; C: A self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS) was placed between the bile duct and the duodenum; D: Endoscopic view showing that the distal end of a SEMS was located at the duodenum.

Table 1.

Published data of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided choledochoduodenostomy (EUS-CDS or HGS) (n > 20)

| Ref. | No. of patients | Study design | CDS or HGS | Stent | Technical success | Complication rate | Patency | Complication |

| Park et al[9] | 55 | P | CDS, HGS | PS, MS | 92, 100 | 21, 19 | 152, 132 | Peritonitis, pneumoperitoneum, Bleeding |

| Hara et al[11] | 18 | P | CDS | PS | 94 | 17 | 272 | Peritonitis, hemobilia |

| Khashab et al[25] | 20 | R | CDS, HGS | PS, MS | 100 | 10 | - | NA |

| Kawakubo et al[8] | 64 | R | CDS, HGS | PS, MS | 95, 95 | 14, 30 | - | Bile leak, stent misplacement, bleeding |

| Hara et al[12] | 18 | P | CDS | MS | 94 | 11 | NR | peritonitis |

| Vila et al[10] | 65 | R | CDS, HGS | NA | 86, 65 | 15, 29 | - | Biloma, bleeding, perforation, pancreatitis, cholangitis, hematoma, abscess, pseudocyst |

| Dhir et al[13] | 30 | R | CDS, HGS | MS | 92.3 | 20 | - | Cholangitis, perforation, bile leak, pneumoperitoneum, death |

P: Prospective; R: Retrospective; CDS: Choledochoduodenostomy; HGS: Hepaticogastrostomy; PS: Plastic stent; MS: Metallic stent; NA: Not available; NR: Not reached.

EUS-HGS is performed to create a fistula between the left intrahepatic bile duct and the stomach (Figure 2). The indication for EUS-HGS is similar to that for EUS-CDS, that is, palliation of distal malignant biliary obstruction. However, EUS-HGS could be also performed in patients with altered upper gastrointestinal tract anatomy or gastric outlet obstruction. In addition, palliation of a left intrahepatic bile duct with a malignant hilar biliary obstruction is possible with EUS-HGS[23,24]. The technical success rate with EUS-HGS is 81%-100% (Table 1)[8,9,13,25]. EUS-HGS itself has serious complications, however, because the fistula traverses the peritoneum[26]. The complication rate ranges from 19% to 30%. Common complications are pneumoperitoneum, bleeding, bile leak, cholangitis, and stent migration. In particular, inward stent migration can be fatal. It is important to manage these complications[27,28]. To prevent inward stent migration, a longer stent might be better and it should be deployed not under fluoroscopic guidance but rather direct endoscopic visualization. Although some specialized SEMSs for EUS-HGS have been developed[22], highly dedicated SEMSs for EUS-HGS are necessary to reduce the complication rate. Recently, the feasibility of EUS-HGS for treating isolated right intrahepatic bile duct was reported[29,30]. Also, bilateral EUS-HGS for palliation of hilar malignant biliary obstruction could be feasible in the near future.

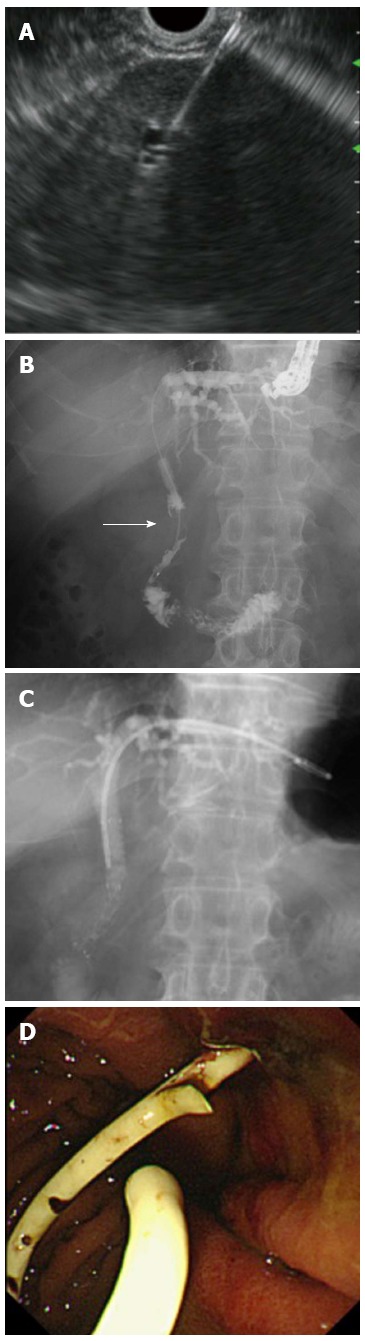

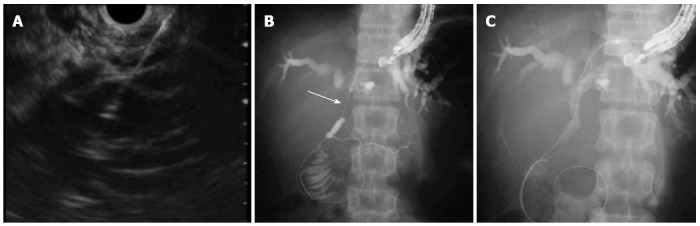

Figure 2.

Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided hepaticogastrostomy. A: Left intrahepatic bile duct was punctured; B: Cholangiography showing distal malignant stricture (arrow); C: Following antegrade self-expandable metallic stent placement, a plastic stent was deployed between the intrahepatic bile duct and stomach; D: Endoscopic view showing that the distal end of the plastic stent was located at the stomach.

EUS-GBD is performed to create a fistula between the gallbladder and gastrointestinal tract (stomach or duodenum) (Figure 3). This procedure is indicated for drainage in patients with acute cholecystitis as an alternative to percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD), and who are not suitable candidates for emergency cholecystectomy. The technical success rate is reported to be around 100% (Table 2)[31-33]. A plastic stent or nasobiliary tube is used in patients with temporary stent placement, whereas SEMSs are used for patients who are not suitable for future cholecystectomy. Jang et al[33] reported that the technical and clinical success rates for EUS-GBD were similar to those for PTGBD. Also, the pain scores were lower following EUS-GBD than after PTGBD in patients prior to cholecystectomy. A recent report indicated that, if a specialized SEMS is used, EUS-GBD is feasible for patients who are not suitable candidates for elective cholecystectomy[34]. In the future, EUS-GBD might be the treatment of choice for acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients.

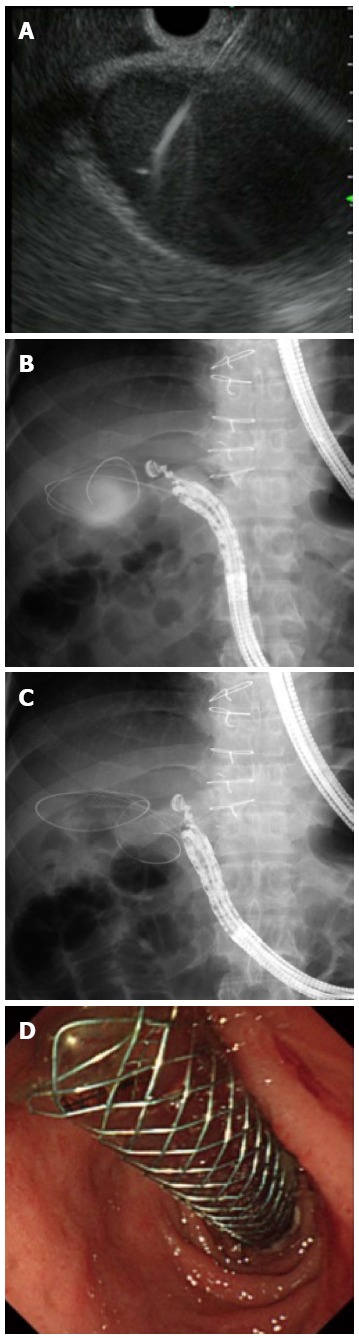

Figure 3.

Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided gallbladder drainage. A: Endoscopic ultrasonography showing that the gallbladder was punctured by the needle; B: Guidewire was advanced through the needle into the gallbladder; C: A self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS) was placed between the gallbladder and the duodenum; D: Endoscopic view showing that distal end of a SEMS was located at the stomach.

Table 2.

Published data of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided gallbladder drainage (n > 10)

| Ref. | No. of patients | Study design | Stent | Technical success | Complication rate | Complication |

| Jang et al[33] | 30 | P | ENBD | 97% | 7% | Pneumoperitoneum |

| Choi et al[32] | 63 | R | MS | 98% | 5% | Perforation, pneumoperitoneum |

P: Prospective; R: Retrospective; ENBD: Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage; MS: Metallic stent.

EUS-RV

An indication for the EUS-RV is biliary cannulation in patients who have failed biliary cannulation in conventional ERCP. For EUS-RV, the bile duct is punctured and a guidewire is advanced through the needle to the duodenum. An ERCP-related procedure is then performed using the guidewire. EUS-RV is indicated when biliary access fails during ERCP. There are two biliary access routes depending on the site to be addressed: transhepatic and transduodenal (Figure 4). The transduodenal route is further divided according to the endoscope position: long (push) and short (pull)[35]. The short endoscopic position is referred to as the tip of the endoscope oriented in the caudal direction, while the endoscope is directed cranially in the long endoscopic position. The echoendoscope is advanced into the upper gastrointestinal tract (esophagus, stomach, duodenum and jejunum), and the bile duct is punctured by an FNA biopsy needle. The guidewire is then advanced through the needle antegradely across the papilla to the duodenum. In patients undergoing choledochojejunostomy, the guidewire is passed through the anastomosis to the jejunum. The echoendoscope is then pulled out, keeping the guidewire in place. The ERCP endoscope (duodenoscope or enteroscope) is then advanced to the papilla or the anastomosis where the guidewire has been placed. Biliary access is then achieved alongside or over the guidewire after grasping and withdrawing the instrument through the accessory channel of the endoscope. The biliary intervention is then begun. EUS-RV is indicated when biliary cannulation fails or a biliary stricture cannot be passed. The technical success rate varies from 63% to 98% (Table 3)[10,36-39]. The technical success rate for the transduodenal route is reported to be higher than that for the transhepatic route. Dhir et al[39] noted that the biliary cannulation success rate was higher with EUS-RV than that for the precut technique in patients with difficult ERCP cannulation. The complication rate was around 10%. The most common complications were biliary peritonitis and pancreatitis. Shah et al[38] reported that the transhepatic route could have a tamponade effect and protect against bile leakage, but a prospective study is needed to confirm their results.

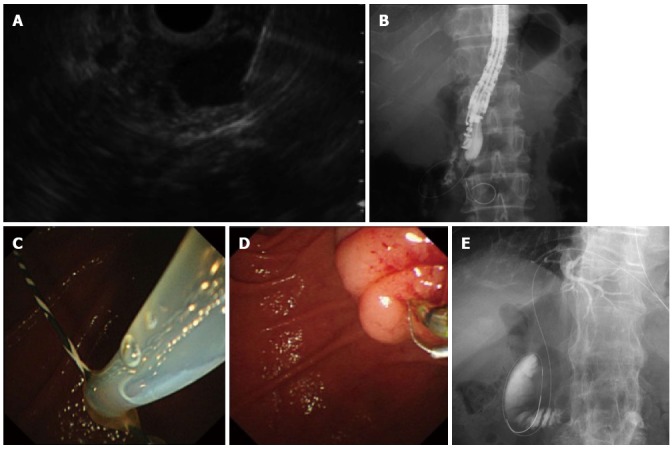

Figure 4.

Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided rendezvous procedure. A: Endoscopic ultrasonography showing that extrahepatic bile duct was punctured by the needle; B: Radiography showing the guidewire was passed through the needle into the duodenum across the papilla antegradely. The endoscope was in the short position; C: Following echoendoscope withdrawal, the duodenoscopic view showed that a guidewire passing through the papilla was grasped by the snare; D: After the guidewire was pulled out through the accessary channel of the duodenoscope, a catheter was inserted into the bile duct over the existing guidewire; E: Transhepatic approach. Abdominal radiography shows that a guidewire was placed through the papilla into the duodenum.

Table 3.

Published data of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided rendezvous procedure (n > 40)

| Ref. | No. of patients | Access route | Technical success | Complication rate | Complication |

| Maranki et al[36] | 49 | TD, TH | 63% | 16% | Pneumoperitoneum, bleeding, peritonitis, aspiration pneumonia |

| Iwashita et al[37] | 40 | TD, TH | 73% | 13% | Pancreatitis, pneumoperitoneum, sepsis |

| Shah et al[38] | 74 | NA | 74% | 8% | Pancreatitis, bile leak, perforation |

| Dhir et al[39] | 58 | TD | 98% | 3% | Bile leak |

| Vila et al[10] | 60 | NA | 68% | 22% | Biloma, bleeding, Perforation, pancreatitis, cholangitis, hematoma, abscess, pseudocyst |

NA: Not available; TD: Transduodenal route; TH: Transhepatic route.

EUS-AT

An indication for EUS-AT is biliary intervention in patients in whom conventional ERCP is impossible. EUS-AT is performed when it is necessary to approach the biliary intervention antegradely through a bilioenteric fistula. Antegrade is the opposite of retrograde in ERCP and is used to maintain bile flow. EUS-AT is indicated, for example, when biliary drainage is needed in patients whose upper gastrointestinal anatomy is altered, or who have malignant gastric outlet obstruction because it is impossible to perform conventional ERCP-related procedures in those patients. EUS-AT is usually performed via the transhepatic route (Figure 5). The echoendoscope is advanced into the upper gastrointestinal tract (esophagus, stomach and jejunum), and the left intrahepatic bile duct is punctured using an FNA biopsy needle. A cholangiogram is then obtained followed by antegrade guidewire insertion through the needle to the duodenum or jejunum across the papilla or the anastomosis. Finally, the biliary intervention is performed antegradely. It is thus possible to perform EUS-AT in patients with altered upper gastrointestinal anatomy[40]. There have been some small case series regarding the feasibility of EUS-AT to treat bile duct stones, malignant biliary obstruction, and anastomotic stricture. The technical success and complication rates for EUS-AT are 57%-100% and 0%-23%, respectively (Table 4)[38,41-43]. Although there are no large case series, the reported complications have been identified as bile leakage, pneumoperitoneum, and bleeding.

Figure 5.

Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided antegrade treatment. A: Left intrahepatic bile duct was punctured; B: Guidewire was advanced through the needle across the stricture (arrow); C: A self-expandable metallic stent was placed antegradely across the stricture.

Table 4.

Published data of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided antegrade treatment (n > 10)

| Ref. | No. of patients | Study design | Stent | Technical success rate | Complication rate | Complication |

| Shah et al[38] | 16 | R | MS | 81% | 6% | Hematoma |

| Park et al[41] | 14 | P | MS | 57% | 0% | - |

| Dhir et al[42] | 35 | R | MS | 97% | 23% | Bleeding, cholangitis, bile leak, pneumoperitoneum |

| Ogura et al[43] | 12 | R | MS | 100% | 8% | Pancreatitis |

MS: Metallic stent; P: Prospective; R: Retrospective.

WHICH TECHNIQUE SHOULD WE SELECT?

In patients with an accessible papilla, any EUS-BD procedure could be possible. Artifon et al[14] reported that the technical and clinical success rates for EUS-CDS and EUS-HGS for treating distal malignant obstruction were similar. Also, Khashab et al[25] reported that the clinical efficacy and safety were similar for EUS-CDS and EUS-RV. Although the complication rate for EUS-RV was relatively lower than that for EUS-BEA, more prospective studies are necessary. For patients with an inaccessible papilla, EUS-HGS and EUS-AT are possible.

There are no data concerning which procedure should be chosen. Hence, it is important to understand the characteristics of each procedure (Table 5).

Table 5.

Important features of each procedure

| EUS-BEA | EUS-RV | EUS-AT | |

| Indication | Patients with malignant biliary obstruction after failed ERCP | Patients with failed biliary cannulation in ERCP | Patients with malignant biliary obstruction after failed ERCP |

| Advantage | Not traversing the malignant stricture | Leading to ERCP related procedure | Possible in patients with altered upper GI anatomy |

| Weak point | Necessity of fistula dilation | Difficult guidewire manipulation | Difficult guidewire manipulation |

| Lack of dedicated stent | Difficulty in patient who was not accessible to the papilla |

ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS-RV: Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided rendezvous procedure; EUS-BEA: Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided bilioenteric anastomosis; GI: Gastrointestinal; US-AT: Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided antegrade treatment.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

There are few data available that compare the clinical efficacy of EUS-BD and ERCP with regard to which is the treatment of choice. Dhir et al[42] reported that the short-term outcomes of EUS-BD (EUS-CDS and EUS-AT) were comparable with those achieved with ERCP. As EUS-BD is performed under direct visualization, it has the potential to substitute for ERCP. A prospective, randomized study is necessary, however, to confirm it. The future development of highly dedicated devices is mandatory.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest to declare.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: March 19, 2015

First decision: April 23, 2015

Article in press: July 15, 2015

P- Reviewer: Rungsakulkij N, Sultan AM S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383–393. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(91)70740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsujino T, Kawabe T, Komatsu Y, Yoshida H, Isayama H, Sasaki T, Kogure H, Togawa O, Arizumi T, Matsubara S, et al. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for bile duct stone: immediate and long-term outcomes in 1000 patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman ML, Guda NM. ERCP cannulation: a review of reported techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:112–125. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02463-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith AC, Dowsett JF, Russell RC, Hatfield AR, Cotton PB. Randomised trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgical bypass in malignant low bileduct obstruction. Lancet. 1994;344:1655–1660. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90455-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robson PC, Heffernan N, Gonen M, Thornton R, Brody LA, Holmes R, Brown KT, Covey AM, Fleischer D, Getrajdman GI, et al. Prospective study of outcomes after percutaneous biliary drainage for malignant biliary obstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2303–2311. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1045-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueller PR, van Sonnenberg E, Ferrucci JT. Percutaneous biliary drainage: technical and catheter-related problems in 200 procedures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982;138:17–23. doi: 10.2214/ajr.138.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giovannini M, Moutardier V, Pesenti C, Bories E, Lelong B, Delpero JR. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided bilioduodenal anastomosis: a new technique for biliary drainage. Endoscopy. 2001;33:898–900. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawakubo K, Isayama H, Kato H, Itoi T, Kawakami H, Hanada K, Ishiwatari H, Yasuda I, Kawamoto H, Itokawa F, et al. Multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage for malignant biliary obstruction in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:328–334. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park do H, Jang JW, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. EUS-guided biliary drainage with transluminal stenting after failed ERCP: predictors of adverse events and long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1276–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vila JJ, Pérez-Miranda M, Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Abadia MA, Pérez-Millán A, González-Huix F, Gornals J, Iglesias-Garcia J, De la Serna C, Aparicio JR, et al. Initial experience with EUS-guided cholangiopancreatography for biliary and pancreatic duct drainage: a Spanish national survey. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1133–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hara K, Yamao K, Niwa Y, Sawaki A, Mizuno N, Hijioka S, Tajika M, Kawai H, Kondo S, Kobayashi Y, et al. Prospective clinical study of EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy for malignant lower biliary tract obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1239–1245. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hara K, Yamao K, Hijioka S, Mizuno N, Imaoka H, Tajika M, Kondo S, Tanaka T, Haba S, Takeshi O, et al. Prospective clinical study of endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy with direct metallic stent placement using a forward-viewing echoendoscope. Endoscopy. 2013;45:392–396. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhir V, Artifon EL, Gupta K, Vila JJ, Maselli R, Frazao M, Maydeo A. Multicenter study on endoscopic ultrasound-guided expandable biliary metal stent placement: choice of access route, direction of stent insertion, and drainage route. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:430–435. doi: 10.1111/den.12153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Artifon EL, Aparicio D, Paione JB, Lo SK, Bordini A, Rabello C, Otoch JP, Gupta K. Biliary drainage in patients with unresectable, malignant obstruction where ERCP fails: endoscopic ultrasonography-guided choledochoduodenostomy versus percutaneous drainage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:768–774. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31825f264c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawakami H, Kuwatani M, Kawakubo K, Kudo T, Abe Y, Kubo K, Sakamoto N. Endoscopic salvage technique for spontaneous dislocation and tumor ingrowth of a partially covered, self-expandable metallic stent after endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E58–E59. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1359163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawakami H, Kuwatani M, Sakamoto N. New stent exchange technique following endoscopic ultrasound-guided nasobiliary drainage (with video) Dig Endosc. 2013;25:343–344. doi: 10.1111/den.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawakami H, Kuwatani M, Kawakubo K, Kudo T, Abe Y, Kubo K, Kubota Y, Sakamoto N. Candy-like sign during endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy as an indication of the long distance between the bile duct and duodenal wall. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E406–E407. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawakubo K, Kawakami H, Kuwatani M, Haba S, Kudo T, Abe Y, Sakamoto N. Spontaneous intraductal stent migration after endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochogastrostomy. Endoscopy. 2013;45 Suppl 2 UCTN:E89–E90. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawakubo K, Isayama H, Tsujino T, Sasahira N, Nakai Y, Kogure H, Sasaki T, Yamamoto N, Hirano K, Tada M, et al. Endoscopic retrieval of a migrated stent after endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E370–E371. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itoi T, Binmoeller KF. EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy by using a biflanged lumen-apposing metal stent. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:715. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perez-Miranda M, De la Serna Higuera C, Gil-Simon P, Hernandez V, Diez-Redondo P, Fernandez-Salazar L. EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy with lumen-apposing metal stent after failed rendezvous in synchronous malignant biliary and gastric outlet obstruction (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:342; discussion 343–344. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song TJ, Lee SS, Park do H, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. Preliminary report on a new hybrid metal stent for EUS-guided biliary drainage (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:707–711. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.05.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park do H, Song TJ, Eum J, Moon SH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy with a fully covered metal stent as the biliary diversion technique for an occluded biliary metal stent after a failed ERCP (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park do H, Koo JE, Oh J, Lee YH, Moon SH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. EUS-guided biliary drainage with one-step placement of a fully covered metal stent for malignant biliary obstruction: a prospective feasibility study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2168–2174. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khashab MA, Valeshabad AK, Modayil R, Widmer J, Saxena P, Idrees M, Iqbal S, Kalloo AN, Stavropoulos SN. EUS-guided biliary drainage by using a standardized approach for malignant biliary obstruction: rendezvous versus direct transluminal techniques (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:734–741. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martins FP, Rossini LG, Ferrari AP. Migration of a covered metallic stent following endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy: fatal complication. Endoscopy. 2010;42 Suppl 2:E126–E127. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogura T, Masuda D, Kurisu Y, Edogawa S, Miyamoto Y, Hayashi M, Imoto A, Umegaki E, Uchiyama K, Higuchi K. A novel method for treating bilious vomiting following endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:454–455. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawakubo K, Isayama H, Kogure H, Takahara N, Miyabayashi K, Mizuno S, Mohri D, Sasaki T, Yamamoto N, Nakai Y, et al. Exchange of self-expandable metal stent in endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticogastrostomy. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 2 UCTN:E311–E312. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park SJ, Choi JH, Park do H, Choi JH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. Expanding indication: EUS-guided hepaticoduodenostomy for isolated right intrahepatic duct obstruction (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.04.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogura T, Sano T, Onda S, Imoto A, Masuda D, Yamamoto K, Kitano M, Takeuchi T, Inoue T, Higuchi K. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage for right hepatic bile duct obstruction: novel technical tips. Endoscopy. 2015;47:72–75. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1378111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jang JW, Lee SS, Park do H, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. Feasibility and safety of EUS-guided transgastric/transduodenal gallbladder drainage with single-step placement of a modified covered self-expandable metal stent in patients unsuitable for cholecystectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.03.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi JH, Lee SS, Choi JH, Park do H, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. Long-term outcomes after endoscopic ultrasonography-guided gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis. Endoscopy. 2014;46:656–661. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jang JW, Lee SS, Song TJ, Hyun YS, Park do H, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH, Yun SC. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural and percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage are comparable for acute cholecystitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:805–811. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Itoi T, Binmoeller KF, Shah J, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N, et al. Clinical evaluation of a novel lumen-apposing metal stent for endosonography-guided pancreatic pseudocyst and gallbladder drainage (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:870–876. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawakubo K, Isayama H, Sasahira N, Nakai Y, Kogure H, Hamada T, Miyabayashi K, Mizuno S, Sasaki T, Ito Y, et al. Clinical utility of an endoscopic ultrasound-guided rendezvous technique via various approach routes. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3437–3443. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2896-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maranki J, Hernandez AJ, Arslan B, Jaffan AA, Angle JF, Shami VM, Kahaleh M. Interventional endoscopic ultrasound-guided cholangiography: long-term experience of an emerging alternative to percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography. Endoscopy. 2009;41:532–538. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iwashita T, Lee JG, Shinoura S, Nakai Y, Park DH, Muthusamy VR, Chang KJ. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided rendezvous for biliary access after failed cannulation. Endoscopy. 2012;44:60–65. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah JN, Marson F, Weilert F, Bhat YM, Nguyen-Tang T, Shaw RE, Binmoeller KF. Single-operator, single-session EUS-guided anterograde cholangiopancreatography in failed ERCP or inaccessible papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dhir V, Bhandari S, Bapat M, Maydeo A. Comparison of EUS-guided rendezvous and precut papillotomy techniques for biliary access (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:354–359. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Itoi T, Sofuni A, Tsuchiya T, Ijima M, Iwashita T. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided transhepatic antegrade stone removal in patients with surgically altered anatomy: case series and technical review (with videos) J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:E86–E93. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park do H, Jeong SU, Lee BU, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. Prospective evaluation of a treatment algorithm with enhanced guidewire manipulation protocol for EUS-guided biliary drainage after failed ERCP (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dhir V, Itoi T, Khashab MA, Park do H, Yuen Bun Teoh A, Attam R, Messallam A, Varadarajulu S, Maydeo A. Multicenter comparative evaluation of endoscopic placement of expandable metal stents for malignant distal common bile duct obstruction by ERCP or EUS-guided approach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:913–923. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogura T, Masuda D, Imoto A, Takeushi T, Kamiyama R, Mohamed M, Umegaki E, Higuchi K. EUS-guided hepaticogastrostomy combined with fine-gauge antegrade stenting: a pilot study. Endoscopy. 2014;46:416–421. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]