Abstract

AIM: To compare the efficacy of hepatic resection (HR) and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for patients with solitary huge (≥ 10 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

METHODS: Records were retrospectively analyzed of 247 patients with solitary huge HCC, comprising 180 treated by HR and 67 by TACE. Long-term overall survival (OS) was compared between the two groups using the Kaplan-Meier method, and independent predictors of survival were identified by multivariate analysis. These analyses were performed using all patients in both groups and/or 61 pairs of propensity score-matched patients from the two groups.

RESULTS: OS at 5 years was significantly higher in the HR group than the TACE group, across all patients (P = 0.002) and across propensity score-matched pairs (36.4% vs 18.2%, P = 0.039). The two groups showed similar postoperative mortality and morbidity. Multivariate analysis identified alpha-fetoprotein ≥ 400 ng/mL, presence of vascular invasion and TACE treatment as independent predictors of poor OS.

CONCLUSION: Our findings suggest that HR can be safe and more effective than TACE for patients with solitary huge HCC.

Keywords: Hepatic resection, Transarterial chemoembolization, Solitary huge hepatocellular carcinoma, Overall survival, Propensity score matching

Core tip: Hepatic resection (HR) and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) are the generally accepted treatment options for huge hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (≥ 10 cm), but the most appropriate treatment option for treating solitary huge HCC (≥ 10 cm) is controversial. This subtype of huge HCC involves similar clinicopathology and prognosis as small HCC after HR. Since reports of TACE to treat solitary huge HCC are limited, we compared the efficacy of HR and TACE in a retrospective analysis with and without propensity score matching.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common malignant tumor and the third most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide. More than 660000 new cases of HCC are registered every year, and incidence in most countries appears to be increasing[1,2]. Huge HCC (≥ 10 cm) is common in clinical practice, and hepatic resection (HR) and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) are the generally accepted treatment options. The most appropriate treatment option for huge HCC remains controversial[3]. HR is technically difficult for treating huge HCC because extensive resection is usually required, which may be associated with high risk of mortality and poor prognosis. While TACE should provide reasonable efficacy and low procedure-related mortality based on comparisons of HR and TACE in patients with other types of HCC, studies suggest 5-year overall survival (OS) is < 10% in patients with huge HCC[4,5].

Even less clear is the most appropriate treatment for patients with a subtype of huge HCC known as solitary huge HCC. Several large case series suggest that the large tumor size does not affect prognosis, such that patients with this subtype generally have similar clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis as those with small HCC after HR[6,7]. Moreover, one large case series concluded that HR should be more effective than TACE as initial treatment for huge HCC[3]. The clinical reality is unknown, since we are unaware of direct comparisons of HR and TACE in patients with solitary huge HCC, and few studies have even looked at TACE in these patients.

Therefore we investigated the long-term OS of patients with solitary huge HCC who received HR or TACE. Post-treatment complications and mortality were analyzed, and independent factors associated with prognosis were identified. To reduce patient selection bias inherent in this non-randomized comparison of interventions, we performed propensity score matching to generate pairs of patients from both treatment arms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This retrospective analysis examined patients newly diagnosed with solitary huge HCC (≥ 10 cm) at our hospital between April 2008 and April 2010. Patients were excluded if they showed metastasis at the time of diagnosis or had received any initial HCC treatment, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, supportive care, or sorafenib. Patients were also excluded if they had Child-Pugh C liver function or if medical records were incomplete, such that 5-year OS could not be determined.

HCC diagnosis was confirmed in TACE patients by needle biopsy or by analysis using two image methods [ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)] in conjunction with serum level of α-fetoprotein (AFP) > 400 ng/mL. Needle biopsy was performed in patients with uncertain diagnosis based on imaging and AFP level.

Patients enrolled in the study were assigned to groups based on whether they were treated initially with HR or TACE. Indications for surgery were lack of ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and hypersplenism, as well as the presence of appropriate residual liver volume, as determined by volumetric computed tomography[8,9]. Indications for TACE were lack of ascites, Child-Pugh A liver function or Child-Pugh B liver function with a score of 7, and insufficient estimated residual liver volume for HR[9]. Patients who satisfied the indications for both HR and TACE were treated with HR unless they requested TACE.

Interventions

HR was performed as described[9-11], while TACE was performed as follows. With the patient under local anesthesia, a 4F-to-5F French catheter was introduced into the abdominal aorta via the superficial femoral artery using the Seldinger technique. Hepatic arterial angiography was performed using fluoroscopy to guide the catheter into the celiac and superior mesenteric artery. Then the feeding arteries, tumor, and vascular anatomy surrounding the tumor were identified. A microcatheter was introduced through the 4F-to-5F catheter into the feeding arteries. An emulsion of 5-15 mL lipiodol (Andre Guerbet, Aulnay-sous-Bois, France) and 5-fluorouracil (500 mg/m2) with or without adriamycin (30 mg/m2) was infused into the feeding arteries until blood flow nearly stopped[12]. Follow-up CT scanning was performed one month later to evaluate the effects of TACE. The course was repeated once every 1-2 mo for 2-6 cycles.

Follow-up

Every 2-3 mo after HR or TACE, especially during the first 2 years, patients underwent follow-up liver function testing, serum AFP determination, chest radiography and liver imaging by CT, MRI, and ultrasonography.

Outcome

OS was calculated from the day of surgery until the date of the last follow-up, and survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Since residual viable tumor cells remained after TACE, disease-free survival (DFS) was not used as an outcome to compare the two interventions.

Propensity score matching

We used propensity score matching to reduce potential effects of patient selection bias and baseline differences in this non-randomized comparison of interventions[13]. Matching was performed using the PSM module developed by Felix Thoemmes for SPSS[9]. Propensity scores were estimated for each patient using a logistic regression model based on age, gender, tumor size, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection status, Child-Pugh class, total bilirubin, serum AFP level, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), prothrombin time, albumin and platelet count. One-to-one matching without replacement was performed using a 0.1 caliper width. Then we assessed whether the two groups showed sufficient overlap in their propensity scores to ensure that propensity score matching was feasible in our cohort (data not shown). Balance in the matched cohort was assessed by calculating standardized differences, with differences of < 10% indicating good balance[14].

OS was compared between all patients and between propensity score-matched patients in the HR and TACE groups.

Statistical analysis

Results for continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD and compared between the HR and TACE groups using the t-test. Results for categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Differences in OS were assessed for significance using the log-rank test. Multivariate analysis was carried out using the Cox proportional hazards model to identify independent prognostic factors. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 19.0 (Chicago, IL, United States) using a significance threshold of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

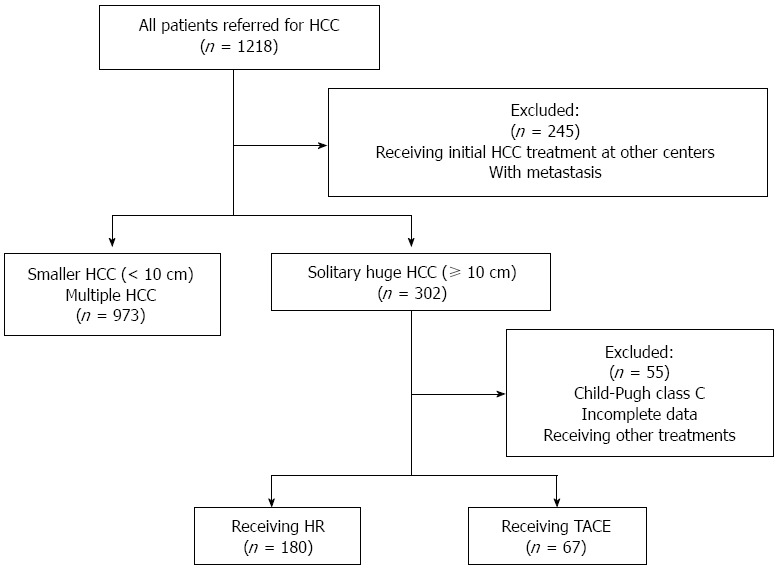

Medical records for 1218 patients newly diagnosed with HCC at our hospital between April 2008 and April 2010 were retrospectively analyzed (Figure 1). Of these patients, 245 were excluded because they had metastasis at the time of diagnosis or had received initial HCC treatment at other centers. Among the remaining 973 patients, 302 had solitary huge HCC (≥ 10 cm). Of these patients, 38 were excluded because they had received other treatments, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, supportive care, or sorafenib; another 17 were excluded because they had Child-Pugh C liver function or medical records were incomplete. The remaining 247 patients were assigned to either a group that received HR (n = 180) or a group that received TACE (n = 67). Patients in the TACE group received a mean of 2.04 ± 0.99 cycles of chemoembolization (range: 1-5).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient selection. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; HR: Hepatic resection; TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization.

The clinicopathological characteristics of the two groups were compared (Table 1). The two groups were similar for all parameters analyzed, except that the HR group contained a significantly greater proportion of HBsAg-positive patients, as well as significantly higher levels of total bilirubin and albumin. The standardized difference of most variables between the two groups was > 10%, indicating that the two groups were not well matched for most baseline characteristics.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic features of all study participants with solitary huge hepatocellular carcinoma (≥ 10 cm) receiving hepatic resection or transarterial chemoembolization n (%)

| Variable | HR (n = 180) | TACE (n = 67) | Standardized difference, % | P-value |

| Age, yr | 46.3 ± 11.9 | 48.1 ± 12.4 | 14.2 | 0.307 |

| M/F | 158 (87.8)/22 (12.2) | 64 (95.5)/3 (4.5) | 37.2 | 0.073 |

| Tumor size, cm | 11.3 ± 2.2 | 11.9 ± 2.2 | 26.7 | 0.059 |

| HBsAg (+) | 153 (85) | 65 (97.0) | 70.1 | 0.009 |

| Child-Pugh class | ||||

| A | 175 | 64 | 8.2 | 0.790 |

| B | 5 | 3 | ||

| Cirrhosis | 133 (73.9) | 57 (85.1) | 31.2 | 0.064 |

| AFP | ||||

| ≥ 400 ng/mL | 75 (41.7) | 37 (55.2) | 27.1 | 0.057 |

| ≤ 400 ng/mL | 105 (58.3) | 30 (44.8) | ||

| Total bilirubin, μmol/L | 13.4 ± 5.9 | 16.1 ± 8.4 | 37.6 | 0.004 |

| ALT, U/L | 50.7 ± 52.4 | 63.6 ± 44.5 | 29.1 | 0.074 |

| AST, U/L | 60.6 ± 40.9 | 56.0 ± 35.4 | 13.0 | 0.418 |

| Prothrombin time, s | 12.8 ± 1.4 | 13.1 ± 2.3 | 9.7 | 0.355 |

| Albumin, g/L | 39.4 ± 4.6 | 37.5 ± 6.5 | 29.0 | 0.012 |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 210.0 ± 77.6 | 213.4 ± 89.4 | 3.8 | 0.771 |

| Vascular invasion | 26 (14.4) | 6 (9.0) | 19.1 | 0.253 |

Values with ‘‘±’’ are written as mean ± SD or number (%) of patients. ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein; HR: Hepatic resection; TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization.

Propensity score matching

Propensity score matching generated 61 pairs of patients, for which baseline characteristics showed no significant differences (P > 0.05) and for which the standardized difference was < 10% for all parameters (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinicopathologic features of propensity score-matched study participants with solitary huge hepatocellular carcinoma (≥ 10 cm) receiving hepatic resection or transarterial chemoembolization n (%)

| Variables | HR (n = 61) | TACE (n = 61) | Standardized difference, % | P-value |

| Age (yr) | 46.3 ± 11.9 | 48.1 ± 12.4 | 4.3 | 0.808 |

| Gender (M/F), n (%) | 58 (95.1)/3 (4.9) | 58 (95.1)/3 (4.9) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 11.9 ± 3.0 | 11.8 ± 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.915 |

| HBsAg (+) | 60 (98.4) | 60 (98.4) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Child-Pugh class | ||||

| A | 58 | 58 | 0 | 1.000 |

| B | 3 | 3 | ||

| Cirrhosis | 52 (85.2) | 51 (83.6) | 4.4 | 0.803 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | ||||

| ≥ 400 | 31 (50.8) | 32 (52.5) | 3.3 | 0.856 |

| ≤ 400 | 30 (49.2) | 29 (47.5) | ||

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 13.6 ± 6.8 | 15.1 ± 8.1 | 8.9 | 0.261 |

| ALT (U/L) | 59.0 ± 56.5 | 60.2 ± 42.6 | 3.0 | 0.888 |

| AST (U/L) | 57.6 ± 30.3 | 57.4 ± 36.3 | 0.4 | 0.983 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 12.7 ± 1.4 | 13.0 ± 2.3 | 9.7 | 0.504 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 37.7 ± 4.6 | 37.7 ± 6.6 | 0.5 | 0.972 |

| Platelet count (109/L) | 218.1 ± 86.9 | 213.0 ± 88.6 | 3.8 | 0.750 |

| Vascular invasion | 5 (8.2) | 6 (9.8) | 5.5 | 0.752 |

Values with ‘‘±’’ are written as mean ± SD. ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein; HR: Hepatic resection; TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization.

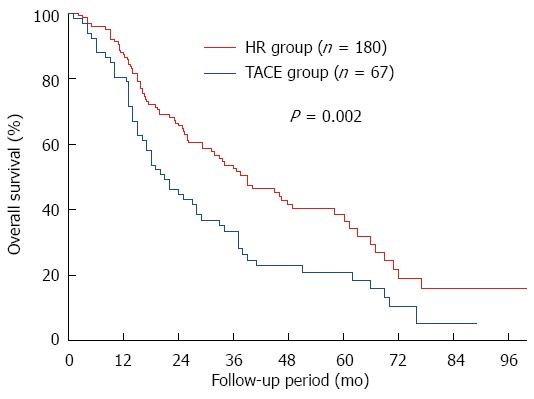

OS

Median follow-up across all patients (without propensity score matching) was 47.1 mo in the HR group and 33.4 mo in the TACE group. OS was significantly higher in the HR group at 1 year (87.4% vs 80.6%), 3 years (52.7% vs 33.4%), and 5 years (38.7% vs 20.8%) (P = 0.002; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of overall survival across all study participants with solitary huge hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing hepatic resection or transarterial chemoembolization. HR: Hepatic resection; TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization.

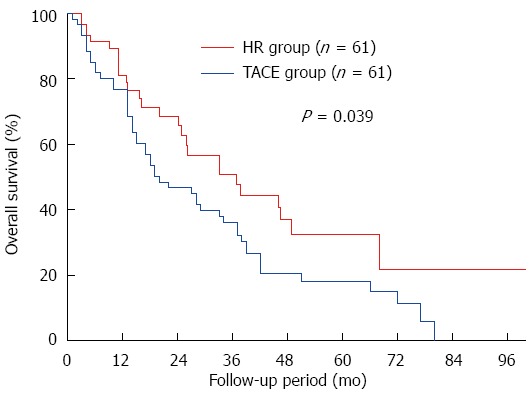

Median follow-up among the propensity score-matched pairs was 49.7 mo in the HR group and 32.6 mo in the TACE group. OS was significantly higher in the HR group at 1 year (89.1% vs 76.9%), 3 years (55.4% vs 36.1%), and 5 years (36.4% vs 18.2%) (P = 0.039; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of overall survival across propensity score-matched study participants with solitary huge hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing hepatic resection or transarterial chemoembolization. HR: Hepatic resection; TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization.

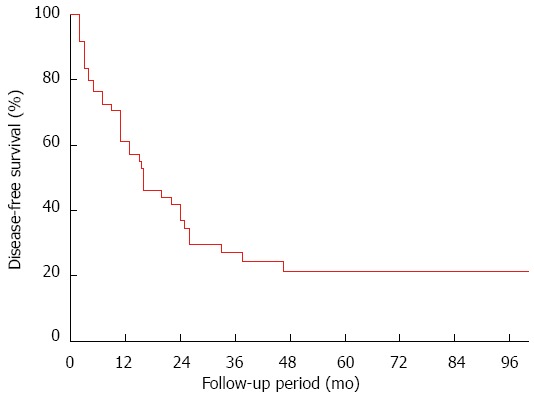

Tumor recurrence

Among the 61 propensity score-matched patients in the HR group, recurrence occurred in 20 (32.8%), 12 of whom suffered intrahepatic recurrence, 2 extrahepatic recurrence and 6 concurrent intra- and extrahepatic recurrence. Nine of the 20 patients received additional treatment, including re-resection (n = 4), TACE (n = 3) and ablation (n = 2). DFS for propensity score-matched patients who received HR was 61.2% at 1 year, 27.1% at 3 years and 21.3% at 5 years (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Disease-free survival in propensity score-matched patients with solitary huge hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing hepatic resection.

Safety

Across all patients in the study, two patients in the HR group and one patient in the TACE group died within 30 d of treatment (P = 1.000). Mortality at 90 d was also similar in both groups (3.3% vs 3.0%; P = 1.000), as was the incidence of postoperative complications. The most common complication was hydrothorax in the HR group (3.9) and liver failure in the TACE group. Across the 61 pairs of propensity score-matched patients, the HR and TACE groups again showed similar mortality at 30 and 90 d (P = 1.000 for both). Liver failure was the most common complication in both groups. Specific complications in the two groups are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Treatment outcomes in patients with solitary huge hepatocellular carcinoma receiving hepatic resection or transarterial chemoembolization, before and after propensity score matching n (%)

|

Before matching |

After matching |

|||||

| HR (n = 180) | TACE (n = 67) | P-value | HR (n = 61) | TACE (n = 61) | P-value | |

| 30-d mortality | 2 (1.1) | 1 (1.5) | 1.000 | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.6) | 1.000 |

| 90-d mortality | 6 (3.3) | 2 (3.0) | 1.000 | 3 (4.9) | 2 (3.3) | 1.000 |

| Postoperative complications | 36 (20.0) | 11 (16.4) | 0.524 | 14 (23.0) | 10 (16.4) | 0.362 |

| Liver failure | 5 (2.8) | 5 (7.5) | 0.194 | 4 (6.6) | 4 (6.6) | 1.000 |

| Bleeding | 4 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 0.507 | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Wound infection | 5 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 0.384 | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 0.476 |

| Puncture hematoma | 0 (0) | 3 (4.5) | 0.019 | 0 (0) | 3 (4.9) | 0.242 |

| Bile fistula | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Pulmonary infection | 6 (3.3) | 3 (4.5) | 0.964 | 2 (3.3) | 3 (4.9) | 1.000 |

| Incision dehiscence | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Abdominal infection | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 0.565 | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Hydrothorax | 7 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 0.228 | 4 (6.6) | 0 (0) | 0.127 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1.000 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

HR: Hepatic resection; TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization.

Identification of prognostic factors for OS

Cox proportional hazards regression of data from the 61 pairs of propensity score-matched patients identified several predictors of OS (Table 4). Univariate analysis identified three predictors of increased risk of poor OS, all of which were confirmed by multivariate analysis: AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL (HR = 1.997, 95%CI: 1.259 to 3.166, P = 0.003), vascular invasion (HR = 2.347, 95%CI: 1.051 to 5.242, P = 0.037) and TACE treatment (HR = 2.492, 95%CI: 1.550 to 4.006, P < 0.001).

Table 4.

Prognostic factors predicting overall survival in propensity score-matched patients with solitary huge hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing hepatic resection or transarterial chemoembolization

| Variable |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

||||

| HR | 95%CI | P-value | HR | 95%CI | P-value | |

| Age (yr) | 0.988 | 0.970-1.007 | 0.220 | |||

| Gender (M/F) | 1.459 | 0.357-5.962 | 0.599 | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | 1.054 | 0.973-1.141 | 0.197 | |||

| HBsAg (+/-) | 1.391 | 0.340-5.685 | 0.646 | |||

| Child-Pugh class (A/B) | 0.919 | 0.289-2.921 | 0.887 | |||

| Cirrhosis (present/absent) | 1.207 | 0.621-1.611 | 0.579 | |||

| AFP (≥ 400/< 400 ng/mL) | 1.721 | 1.097-2.347 | 0.018 | 1.997 | 1.259-3.166 | 0.003 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 1.025 | 0.994-1.057 | 0.116 | |||

| ALT (U/L) | 1.004 | 1.000-1.009 | 0.052 | |||

| AST (U/L) | 1.003 | 0.997-1.008 | 0.322 | |||

| Prothrombin time (s) | 1.052 | 0.922-1.201 | 0.453 | |||

| Albumin (g/L) | 1.010 | 0.969-1.053 | 0.653 | |||

| Platelet count (109/L) | 0.998 | 0.995-1.001 | 0.190 | |||

| Vascular invasion (present/absent) | 2.335 | 1.057-5.159 | 0.036 | 2.347 | 1.051-5.242 | 0.037 |

| Treatment modality (TACE/hepatic resection) | 2.343 | 1.468-3.741 | < 0.001 | 2.492 | 1.550-4.006 | < 0.001 |

ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein; HR: Hazard ratio; TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization.

DISCUSSION

The present study provides some of the few data available on efficacy and safety of TACE in patients with solitary huge HCC, and we believe it to be the most rigorous direct comparison of HR and TACE in such patients. Our results suggest that HR is safe and effective in these patients and is associated with significantly higher long-term OS than TACE.

One previous study comparing HR and various nonsurgical therapies (hepatic arterial infusion, transcatheter arterial embolization, and percutaneous acetic acid injection) to treat patients with solitary huge HCC found that HR provided longer 5-year OS (24.5% vs 8.2%, P < 0.001)[4]. Consistently, another study reported 5-year OS in such patients to be 7% when not treated by HR[5]. The present study significantly extends that previous work because it minimizes the effects of confounding factors using propensity score matching. In the end, our key finding of longer OS with HR was obtained both across all patients and across propensity score-matched pairs.

The large tumors in solitary huge HCC are surgically challenging because of the increased bleeding, higher risk of liver failure and other complications, and higher postoperative mortality. Nevertheless, surgical techniques have improved substantially in recent years. Mortality in our propensity score-matched patients, regardless of treatment, was 1.6% at 30 d and approximately 3% at 90 d; this is at the low end of the range of 0%-6.9% reported for postoperative 30-d mortality for huge HCC[15]. In addition, both treatments in the propensity score-matched patients showed a 16%-23% rate of complications. These favorable outcomes may reflect the skill and experience of surgeons at our medical center, which annually performs more than 400 HRs on patients with HCC, as well as rigorous patient selection procedures. As a result, liver failure, a well-established complication of HR, occurred with the same frequency (6.6%) in propensity score-matched patients treated by either procedure.

Various prognostic factors for patients with huge HCC have been reported[5-8,15-17], but those studies aggregated data for patients with solitary or multinodular huge HCC. The present study focused on propensity score-matched patients with solitary huge HCC and identified three independent predictors of poor OS: AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL, vascular invasion and TACE treatment. Several European and Japanese reports have stressed the importance of preoperative AFP levels in prognosis, integrating them in prognostic scoring systems[18,19]. Vascular invasion has already been shown to be a risk factor for poor prognosis in HCC[3,7]. Even though our data implicate TACE as a predictor of poor prognosis, several studies, including from our own research group, have suggested that adjuvant TACE after HR can improve survival and reduce risk of recurrence[20-22]. Therefore, the present findings and previous work suggest that combining HR with adjuvant TACE may prove the most effective for treating solitary huge HCC. Future studies should examine this possibility.

Despite its insights, the present study has several important limitations. First, it was a single-center study performed in the Asia-Pacific region, where > 80% of HCC patients have chronic hepatitis B virus infection; this incidence is significantly higher than that in Western countries. Therefore our results may not be representative of all patients with solitary huge HCC. Second, the cohort in our study was enrolled between 2008 and 2010, when the chemotherapeutic agent 5-fluorouracil was routinely used. Current chemotherapeutics may be more effective and less toxic, suggesting that our results may overestimate the clinical advantage of HR over TACE. Third, our study involved relatively few patients and examined them using a non-randomized, retrospective design.

In conclusion, the present work suggests that HR may offer significantly better long-term OS than TACE to patients with solitary huge HCC, with no increase in mortality or morbidity. Large prospective studies are needed to verify and extend these findings.

COMMENTS

Background

Hepatic resection (HR) and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) are the generally accepted treatment options for huge hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (≥ 10 cm). Few studies have examined the safety and efficacy of TACE for a subtype of huge HCC known as solitary huge HCC (≥ 10 cm), and we are unaware of direct comparisons of HR and TACE for such patients.

Research frontiers

This study provides the first direct comparison of HR and TACE in patients with solitary huge HCC, and it provides the most rigorous data so far on the safety and efficacy of TACE in such patients. In addition, the authors use propensity score matching to reduce the potential bias in our non-randomized comparison of interventions.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This study provides the first direct evidence that, after controlling for confounders, HR provides better long-term overall survival than TACE for solitary huge HCC.

Applications

This study may help guide clinicians in choosing the optimal treatment for their patients with solitary huge HCC. It also lays the groundwork for future research, particularly large, prospective studies comparing HR and TACE in patients inside and outside the Asia-Pacific region, where chronic hepatitis B infection often co-occurs with HCC.

Terminology

HR and TACE are the generally accepted treatment options for huge HCC (≥ 10 cm). Solitary huge HCC (≥ 10 cm) was reported a specific subtype of huge HCC which has clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis similar to that of small HCC after HR. No direct comparative study of the treatment outcomes of HR and TACE in solitary huge HCC patients has been performed to date.

Peer-review

This article includes important data. The authors collected a consecutive series of 247 huge HCCs. Among them 67 HCCs received TACE and the other 180 HCCs received HR. Sixty-one pairs of matched patients were selected from each treatment arm by conducting propensity score matching. They found that survival rate was better in the HR group than in the TACE group.

Footnotes

Supported by National Science and Technology Major Special Project, No. 2012ZX10002010001009; Self-Raised Scientific Research Fund of the Ministry of Health of Guangxi Province, No. Z2015621 and No. Z2014241; and Guangxi University of Science and Technology Research Fund, No. KY2015LX056.

Institutional review board statement: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Affiliated Tumor Hospital of Guangxi Medical University and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent statement: All study participants or their legal guardian provided informed written consent prior to enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors disclose no conflicts.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: February 11, 2015

First decision: March 10, 2015

Article in press: July 8, 2015

P- Reviewer: Morise Z, Tai DI S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Venook AP, Papandreou C, Furuse J, de Guevara LL. The incidence and epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a global and regional perspective. Oncologist. 2010;15 Suppl 4:5–13. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-S4-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferenci P, Fried M, Labrecque D, Bruix J, Sherman M, Omata M, Heathcote J, Piratsivuth T, Kew M, Otegbayo JA, et al. World Gastroenterology Organisation Guideline. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): a global perspective. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhong JH, Rodríguez AC, Ke Y, Wang YY, Wang L, Li LQ. Hepatic resection as a safe and effective treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma involving a single large tumor, multiple tumors, or macrovascular invasion. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e396. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mok KT, Wang BW, Lo GH, Liang HL, Liu SI, Chou NH, Tsai CC, Chen IS, Yeh MH, Chen YC. Multimodality management of hepatocellular carcinoma larger than 10 cm. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:730–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang YH, Wu JC, Chen SC, Chen CH, Chiang JH, Huo TI, Lee PC, Chang FY, Lee SD. Survival benefit of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma larger than 10 cm in diameter. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang L, Xu J, Ou D, Wu W, Zeng Z. Hepatectomy for huge hepatocellular carcinoma: single institute’s experience. World J Surg. 2013;37:2189–2196. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang LY, Fang F, Ou DP, Wu W, Zeng ZJ, Wu F. Solitary large hepatocellular carcinoma: a specific subtype of hepatocellular carcinoma with good outcome after hepatic resection. Ann Surg. 2009;249:118–123. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181904988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsieh CB, Yu CY, Tzao C, Chu HC, Chen TW, Hsieh HF, Liu YC, Yu JC. Prediction of the risk of hepatic failure in patients with portal vein invasion hepatoma after hepatic resection. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:72–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhong JH, Xiang BD, Gong WF, Ke Y, Mo QG, Ma L, Liu X, Li LQ. Comparison of long-term survival of patients with BCLC stage B hepatocellular carcinoma after liver resection or transarterial chemoembolization. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu SL, Ke Y, Peng YC, Ma L, Li H, Li LQ, Zhong JH. Comparison of long-term survival of patients with solitary large hepatocellular carcinoma of BCLC stage A after liver resection or transarterial chemoembolization: a propensity score analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhong JH, Ke Y, Gong WF, Xiang BD, Ma L, Ye XP, Peng T, Xie GS, Li LQ. Hepatic resection associated with good survival for selected patients with intermediate and advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2014;260:329–340. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung GE, Lee JH, Kim HY, Hwang SY, Kim JS, Chung JW, Yoon JH, Lee HS, Kim YJ. Transarterial chemoembolization can be safely performed in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma invading the main portal vein and may improve the overall survival. Radiology. 2011;258:627–634. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10101058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ke Y, Zhong J, Guo Z, Liang Y, Li L, Xiang B. [Comparison liver resection with transarterial chemoembolization for Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage B hepatocellular carcinoma patients on long-term survival after SPSS propensity score matching] Zhonghua Yi Xue Zazhi. 2014;94:747–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Agostino RB. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265–2281. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shrager B, Jibara GA, Tabrizian P, Schwartz ME, Labow DM, Hiotis S. Resection of large hepatocellular carcinoma (≥10 cm): a unique western perspective. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:111–117. doi: 10.1002/jso.23246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allemann P, Demartines N, Bouzourene H, Tempia A, Halkic N. Long-term outcome after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma larger than 10 cm. World J Surg. 2013;37:452–458. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1840-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi GH, Han DH, Kim DH, Choi SB, Kang CM, Kim KS, Choi JS, Park YN, Park JY, Kim do Y, et al. Outcome after curative resection for a huge (> or=10 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma and prognostic significance of gross tumor classification. Am J Surg. 2009;198:693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Predictive factors for long term prognosis after partial hepatectomy for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. The Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan. Cancer. 1994;74:2772–2780. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941115)74:10<2772::aid-cncr2820741006>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.A new prognostic system for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 435 patients: the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) investigators. Hepatology. 1998;28:751–755. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukuda S, Okuda K, Imamura M, Imamura I, Eriguchi N, Aoyagi S. Surgical resection combined with chemotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombus: report of 19 cases. Surgery. 2002;131:300–310. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.120668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xi T, Lai EC, Min AR, Shi LH, Wu D, Xue F, Wang K, Yan Z, Xia Y, Shen F, et al. Adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a non-randomized comparative study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:1198–1203. doi: 10.5754/hge09654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhong JH, Ma L, Li LQ. Postoperative therapy options for hepatocellular carcinoma. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:649–661. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.905626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]