Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy of Bounce Back Now (BBN), a modular, web-based intervention for disaster-affected adolescents and their parents.

Method

A population-based randomized controlled trial used address-based sampling to enroll 2,000 adolescents and parents from communities affected by tornadoes in Joplin, MO, and Alabama. Data collection via baseline and follow-up semi-structured telephone interviews was completed between September 2011 and August 2013. All families were invited to access the BBN study web portal irrespective of mental health status at baseline. Families who accessed the web portal were assigned randomly to 3 groups: (1) BBN, which featured modules for adolescents and parents targeting adolescents’ mental health symptoms; (2) BBN plus additional modules targeting parents’ mental health symptoms; or (3) assessment only. The primary outcomes were adolescent symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression.

Results

Nearly 50% of families accessed the web portal. Intent-to-treat analyses revealed time × condition interactions for PTSD symptoms (B=−0.24, SE=0.08, p<.01) and depressive symptoms (B=−0.23, SE=0.09, p<.01). Post-hoc comparisons revealed fewer PTSD and depressive symptoms for adolescents in the experimental vs. control conditions at 12-month follow-up (PTSD: B=−0.36, SE=0.19, p=.06; depressive symptoms: B=−0.42, SE=0.19, p=0.03). A time × condition interaction also was found favoring the BBN vs. BBN + parent self-help condition for PTSD symptoms (B=0.30, SE=0.12, p=.02), but not depressive symptoms (B=0.12, SE=0.12, p=.33).

Conclusion

Results supported the feasibility and initial efficacy of BBN as a scalable disaster mental health intervention for adolescents. Technology-based solutions have tremendous potential value if found to reduce the mental health burden of disasters.

Keywords: adolescents, disaster mental health, technology, posttraumatic stress, depression

INTRODUCTION

A single disaster can adversely affect thousands or millions of families simultaneously. Adolescents are a vulnerable and understudied population. Most youth do not develop serious mental health problems after disasters, but many develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and substance abuse.1,2 Few disaster mental health interventions have undergone rigorous scientific evaluation; those that have are typically resource intensive and difficult to deploy.3–4 Scalable, sustainable interventions have tremendous potential value if found to reduce the psychological, health-related, and economic burden of disasters.5 Web-based self-help approaches may help to address this critical gap in resources.5–6

Adolescents and adults routinely use the Internet as a source of health information.7 Web-based approaches present an opportunity to deliver evidence-based resources widely and at low cost via any Internet-accessible device.6,7 Web interventions can be optimized to a range of mobile devices (e.g., smartphone, tablet) and can be interactive, accessed privately, tailored, easily updated and refined over time, and include multiformat content (written, video, audio).8 Interventions that are tailored and/or fully automated (i.e., do not require direct interaction with a mental health provider) may address common barriers to traditional care, including stigma, scheduling, transportation, and cost. Technology-based interventions have performed well in several methodologically rigorous efficacy studies as adjuncts to clinician-directed treatment and as front-line interventions with minimal or no clinician contact.6,9,10 However, no research has evaluated the efficacy of web-based self-help mental health interventions for youth affected by disasters,3–6 signaling the need for this study.

This study consisted of a randomized, controlled population-based trial of Bounce Back Now (BBN), a modular Web-based intervention for disaster-affected adolescents and parents. BBN targets common mental health correlates of disasters, including PTSD, depressed mood, and substance use problems. We hypothesized that youth whose families accessed BBN (i.e., teen, parent, or both) would report greater reductions in symptoms of PTSD, depression, and substance use than youth assigned to the assessment-only control condition. A secondary research question assessed the incremental utility of a separate multi-module adult self-help intervention that was made available to a randomly selected subsample of parents.

METHOD

Study Design

Address-based sampling was used to recruit 2,000 families living in communities affected by devastating tornadoes that affected Joplin, MO, and several areas of Alabama in 2011. Semi-structured baseline telephone interviews were conducted between September 2011 and June 2012. One designated parent participant was interviewed, followed by a randomly selected (if necessary) adolescent. Parents and adolescents were given a unique password and access to the study web portal at the end of the baseline interview. Families were randomized to 1 of 3 conditions after accessing the study website: (1) BBN for disaster-affected youth (i.e., youth and parent modules addressing adolescent post-disaster mental health), (2) BBN plus a 7-module adult self-help (ASH) intervention targeting parents’ mental health and substance use problems, or (3) an assessment only web-based Control condition. Follow-up interviews were conducted 4 and 12 months post-baseline. Data collection was completed in August, 2013.

Setting and Sampling Frame

Families were recruited from two regions that sustained severe impact from tornadoes. On April 27, 2011, northern Alabama experienced a historic 39 tornadoes ranging from Enhanced Fujita (EF) scale categories 4 (winds 166–200mph) to EF-5 (winds > 200mph). The tornadoes caused significant property damage, injury, and death. Over 14,000 homes were destroyed or uninhabitable, 2,200 people were injured, and 240 individuals lost their lives.11–13 On May 22, 2011, an EF-5 tornado struck Joplin, MO, leaving over 150 dead and 1,000 injured, and almost 7,000 homes destroyed.14 Families living in close geographic proximity to the paths of these tornadoes were considered most likely to benefit from the intervention under study.

A highly targeted address-based sampling strategy ensured precision in defining the sampling frame. This was necessary due to the localized nature of tornadoes; traditional random-digit-dial (RDD) approaches cannot be applied to narrowly defined, community-level recruitment. Recruitment of cell-phone-only households was another key advantage of this strategy over traditional RDD methodologies. Tornado track severity and latitude/longitude coordinates obtained from NOAA12,14 incident reports defined the sampling frame. The distances of the radii surrounding the latitude/longitude coordinates (5 miles for EF-4/EF-5; 2 miles for EF-2/EF-3) ensured that a high percentage of households were recruited from neighborhoods directly affected by the tornadoes.

Participants

The sample consisted of 2,000 adolescents (M age=14.5, SD=1.7) with roughly equal gender distribution (boys: n=981, 49.0%; girls: n=1019, 51.0%). Race was 62.5% White, 22.6% Black, and 3.8% other (11.1% declined); 2.7% reported Hispanic ethnicity. Most households had partnered parents (73.4%). Median annual income was between $40,000 and $60,000 in the sample, consistent with U.S. Census estimates of household income in Alabama and Missouri. Nearly 1 in 4 families (24%) reported household incomes under $20,000. Most (71.1%) parents reported at least some college education. More mothers (73.7%) participated than fathers (26.3%). Nearly all households had internet access (only 2.1% of screen-outs were excluded on the basis of this criterion), consistent with national data from the Pew Internet and American Life Project indicating that over 95% of families with school-aged children access the internet.

Reports from the baseline interview revealed that over 90% of participants were present in the affected area when the tornado touched down. Roughly 75% of caregivers reported concern about the safety or whereabouts of family members. Physical injury was uncommon (2.9%). Nearly one-tenth of families experienced displacement, with many families reporting loss or damage to residence (40%), cars (19%), other household contents (18%), sentimental possessions (10%), and pets (4%).

Intervention: Experimental Conditions

Families assigned to the BBN or BBN+ASH conditions received BBN, a modular intervention in which adolescents and parents self-selected the content they wished to access. Four multi-session modules were available to adolescents addressing PTSD symptoms, Cigarette Use, Alcohol Use, and symptoms of Depression (the modules were labeled “Stress,” “Smoking,” “Alcohol,” and “Moods,” respectively). Adolescents were permitted to access as many modules as they chose.

After entering the PTSD, Cigarette Use, or Depression module, a brief screener assessed hallmark symptoms (e.g., avoidance of trauma cues, loss of interest or pleasure in activities) to ensure relevance of the module to adolescents’ needs. Adolescents who endorsed 2 or more symptoms of depression, 3 or more PTSD symptoms, or tobacco use were identified as a positive screen and encouraged to complete the respective module. Those with a negative screen were invited (but not required) to exit the module. No screening mechanism was used for adolescents who accessed the Alcohol Use module because it was intended to be preventative.

It was anticipated that many adolescents would only make a single visit to the site. For this reason, adolescents’ first visit to a module exposed them to most of the basic education addressed within that module. Content was guided by behavioral principles and procedures associated with efficacious behavioral interventions.15,16 The PTSD module provided education as well as evidence-based recommendations focused on exposure, reduction of avoidance of traumatic cues, coping strategies, and anxiety management.17 The Depression module featured behavioral activation strategies, which have shown promise as easily understood, efficacious, parsimonious, and cost effective approaches in treatment of depression.18,19 The Cigarette Use and Alcohol Use modules made use of combined brief motivational-enhancement and cognitive-behavioral strategies that have received support in the literature.20,21 Content was displayed using different media to enhance engagement (e.g., text, graphics, animations, videos, quizzes).

Once adolescents completed an initial visit, they were encouraged to return to the site to track their progress and receive additional education. Adolescents who returned to the module (roughly 50% of adolescents and 53% of parents who accessed the site visited the site at least twice22) were provided a brief symptom tracking activity and were prompted to indicate barriers that they had experienced in carrying out recommendations from their prior visit (e.g., not enough time in the day, transportation barriers, limited support network). Motivational and educational content was provided in response to each barrier the user endorsed.

Parents who accessed BBN were presented one module with four primary components addressing parent-adolescent communication, psychoeducation relating to common post-disaster mental health problems, adolescent internalizing problems, and adolescent problematic behavior. Parents were permitted to access as many of these components as they chose. Parents assigned to the BBN+ASH condition also were provided access to a separate portal on the site that directed them to seven self-help modules designed to address their own mental health. This adult disaster mental health intervention, Disaster Recovery Web, has been described in detail elsewhere and has performed well in feasibility testing.8,22

Comparison Condition

Control condition content included questions assessing knowledge of prevalent disaster mental health problems, including myths and facts questions that were used to deliver education in the experimental conditions. No education or feedback was provided. Control participants did not receive any recommendations featured in the experimental conditions.

Measures

Structured baseline and 4- and 12-month post-baseline telephone interviews assessed demographics, mental health functioning, and substance use. Highly trained interviewers employed by Abt SRBI—a large survey research firm—used computer-assisted telephone interview methodology, which maximized efficiency by supporting skip patterns and minimizing errors in administration. Branching logic was minimized for data quality purposes.

Adolescent PTSD symptoms were assessed using the National Survey of Adolescents (NSA) PTSD module,23 which addressed DSM-IV symptom criteria for PTSD based on presence of each symptom for two weeks or longer during the past month. This measure has strong reliability and concurrent validity.23

Adolescent depressive symptoms were assessed using the NSA Depression module. This structured diagnostic interview assessed for the presence of each DSM-IV major depressive episode (MDE) symptom criterion for a period of two weeks or longer during the past month. Psychometric data support the scale’s internal consistency and convergent validity.23

Adolescent alcohol use and binge drinking was assessed using a series of questions adapted from the NSA substance use modules.24 Alcohol use was assessed with 3 questions. First, adolescents were asked whether they had ever used alcohol. Next, they were asked to estimate the frequency of their alcohol use over the prior 30 days. Third, they were asked to estimate the average number of drinks they consumed on days that they drank alcohol. Binge drinking frequency was based on adolescents’ reports of the number of times in the past 30 days in which they consumed 4 (girls) or 5 (boys) alcoholic beverages.25

Adolescent cigarette use was assessed as use of cigarettes in the past 30 days. Two questions were used to distinguish between adolescents who were regular vs. infrequent tobacco users. Adolescents were asked if they ever used cigarettes and then were asked if their lifetime use exceeded 100 cigarettes. Those who endorsed these items were asked if they had used cigarettes in the past 30 days; this question identified current smokers.

Procedure

Eligible families were recruited via a two-stage process. First, we identified households in the designated sampling regions with a landline telephone match in public listings. Second, households without a landline telephone match, most being cell-phone-only households, were mailed a letter describing the study and a brief eligibility screen. Families received $5 regardless of eligibility for returning the screen. The survey research firm contacted households within both the landline-matched and mail-screen samples to assess study eligibility.

Verbal informed consent was obtained from parents and adolescents. Families were eligible to participate if they had an adolescent aged 12–17 years and resided at their household address at the time of the tornado. Exclusion criteria included residence in an institutional setting, households without Internet or telephone access, and non-English speakers (budget restrictions precluded translating the intervention at this stage of evaluation).

The baseline interview averaged 25 min. It was conducted between September, 2011, and June, 2012, an average of 8.8 months after tornado exposure (SD=2.6, range=4.0–13.5). The overall cooperation rate, calculated according to the American Association for Public Opinion Research industry standards (i.e., [number screened] divided by [number screened + screen-outs + unknown eligibility]), was 61%. After the baseline interview, participants were given instructions and unique user identifiers (IDs) to access the study Website. Parents and adolescents were assigned different user IDs to ensure access only to parent- or adolescent-oriented content. A letter mailed to the household reviewed these instructions. Interviewers were blind to intervention condition. Families were compensated $15 for completion of each interview and $25 for accessing the study website.

Data Analytic Plan

All analyses were conducted in SPSS. Preliminary comparisons across the intervention conditions were made using one-way ANOVAs and chi-square tests. The same analyses were used to determine if there were differences between those who completed vs. dropped out of the intervention.

An intent-to-treat (ITT) approach was used for the primary outcome analysis such that participants who were randomized to an intervention condition were included in the final outcome analysis. The primary outcome variables were counts of symptoms (i.e., PTSD, depression, frequency of alcohol use, binge drinking episodes). Primary outcomes were analyzed using a generalized estimating equation (GEE), which is an extension of the general linear model. GEE accounts for the autocorrelation associated with repeated measurements and has the flexibility to account for a variety of distributions of outcome variables. A negative binomial distribution was determined as optimal for all outcomes because the distributions were positively skewed with a high proportion of zeros.26 Primary hypotheses were tested with a model that included an intercept that corresponded to baseline, a main effect for time, and a time × condition interaction. The main effect for time indicates that outcomes changed in a linear fashion over the 12-month assessment period. Omitting the main effect of the condition constrains the baseline levels of the outcome variable for the treatment groups to be equal as is appropriate in a randomized trial. Of interest to the current hypotheses is the interaction term. A non-significant interaction term indicates parallel trajectories, or that changes in outcomes do not differ across the intervention and control conditions.27 A significant interaction term indicates non-parallel trajectories, or that intervention and control conditions differ at one or more points. Post-hoc time-point specific comparisons using model-based contrasts as appropriate are conducted to determine at which timepoint the control and intervention conditions differ. This modeling option was chosen because it is generally more powerful than competing strategies for baseline adjustment in longitudinal analyses.27 Hypotheses were addressed with a priori planned contrasts. First, the BBN and BBN+ASH conditions were collapsed and compared to the Control condition. Next, the two experimental conditions were compared to one another. Missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood. Subsequent models included covariates for disaster exposure, number of modules completed, demographic variables, and tornado location.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The intervention conditions did not differ demographically or on baseline assessments of PTSD symptoms, depressive symptoms, use of tobacco in the past 30 days, drinks in the past 30 days, and binge drinking episodes (Table 1). There were no differences in the proportion of BBN (PTSD: 8.0%; depression: 10.1%), BBN+ASH (PTSD: 8.1%; depression: 7.2%), and Control (PTSD: 6.7%; depression: 6.7%) adolescents who met criteria for PTSD (χ2(2)=3.19, p=.20) or major depressive episode (χ2(2)=3.36, p=.19). There were no differences in the number of PTSD and depression symptoms among those who accessed the intervention and those who did not (PTSD symptoms: B=−0.07, p=.18; Depression symptoms: B=0.01, p=.83). There were more female parents (76.1%) in the sample than the non-access sample (71.4%), X2(1)=5.61, p=0.02. There was a small difference in age between the ITT sample (M=44.24; SD=10.13) and the non-access sample (M=45.77; SD=8.32), t(1998)=3.67, p<.001. These differences were not found to moderate outcomes. There was a significant interaction between parent gender, time, and condition for PTSD symptoms (B=−0.30, SE=.13, p=0.03). However, there was no effect of parent gender on treatment at each time point (Baseline: B= −0.05, p=0.22; 4-Month: B=0.12, p=0.79; 12-Month: B=−0.15, p=0.77). It was concluded that the interaction term likely reflects a Type I error. Parent gender was not related to other outcomes. There were no other differences in demographics across groups. Demographic variables, including tornado location, also were unrelated to outcomes.

Table 1.

Demographic data and baseline symptom severity among families randomized to condition (i.e., intent-to-treat) (n = 987)

| BBN (n = 364) |

BBN+ASH (n = 366) |

Control (n = 257) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Adolescent Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | p |

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Gender (% Male) | 171 | 47.0 | 176 | 48.8 | 118 | 45.7 | 0.34 | .845 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 3.50 | .174 | ||||||

| White | 234 | 64.4 | 228 | 62.4 | 168 | 65.3 | ||

| African American | 75 | 20.5 | 95 | 26.1 | 50 | 19.6 | ||

| Hispanic | 8 | 2.1 | 9 | 2.5 | 6 | 2.2 | 0.05 | .976 |

| Tobacco Use | 5 | 1.30 | 6 | 1.00 | 8 | 3.20 | 2.88 | .237 |

|

|

|

|||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | p | |

|

|

|

|||||||

| Age | 14.49 | 1.78 | 14.43 | 1.83 | 14.64 | 1.68 | 0.98 | .377 |

| PTSD Symptoms | 2.73 | 3.65 | 2.26 | 3.25 | 2.54 | 3.35 | 1.86 | .156 |

| Depressive Symptoms | 1.40 | 2.00 | 1.22 | 1.81 | 1.43 | 1.96 | 1.47 | .231 |

| Alcohol Use | 0.43 | 3.03 | 0.67 | 4.38 | 1.12 | 9.25 | 1.09 | .336 |

| Binge Drinking Episodes | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.13 | 0.43 | 0.15 | 0.50 | 0.28 | .757 |

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Parent Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | p |

|

| ||||||||

| Gender (% Male) | 79 | 21.7 | 100 | 27.2 | 58 | 22.6 | 3.56 | .169 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.12 | .942 | ||||||

| White | 265 | 73.0 | 244 | 66.7 | 180 | 70.2 | ||

| African American | 77 | 21.1 | 97 | 26.7 | 63 | 24.4 | ||

| Hispanic | 4 | 1.1 | 6 | 1.7 | 3 | 1.1 | 0.47 | .791 |

|

|

|

|

||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | p | |

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Age | 44.24 | 8.48 | 44.68 | 8.28 | 43.65 | 8.15 | 1.16 | .315 |

Note: BBN = Bounce Back Now intervention; BBN+ASH = Bounce Back Now intervention plus Adult Self Help modules; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

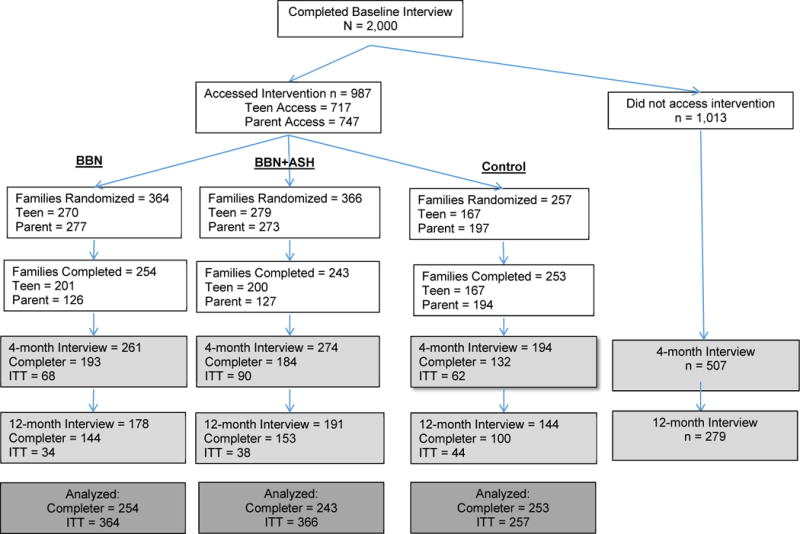

Intent-to-Treat and Completer Samples

All 2,000 families were given access to the study website; 49.4% accessed and 37.5% completed at least one module (Figure 1). This defined the ITT and completer samples. Among those accessing the site, 43.9% accessed all four modules, 13.4% accessed three modules, 14.8% accessed two modules, and 27.9% accessed one module. Among those completing at least one module, 25.8% completed all four modules, 17.9% completed three modules, 21.4% completed two modules, and 34.8% completed one module. Number of modules completed was unrelated to outcomes. Correlates of teen and parent access and completion are summarized elsewhere.22,28 Collapsed across study conditions, no differences were found between the completer and ITT samples on baseline PTSD symptoms [F(1,984)<0.01, p=.98], depressive symptoms [F(1,983)=0.11, p=.74], or alcohol use [F(1,980)=0.23, p=.63]. ITT and completer analyses yielded similar results except where noted. Results of ITT analyses are reported.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram.

Note: Families are defined as having either a teen or parent access the intervention. All families were contacted for follow-up interviews, irrespective of their involvement with the intervention. Intent-to-treat (ITT) includes all participants who accessed the intervention. Completer/Completed = completer sample; includes all participants in which a family member (teen or parent) completed at least one intervention module. Lightly shaded boxes refer to interview participation, whereas the prior two rows of unshaded boxes refer to web access and completion, respectively. BBN = Bounce Back Now. BBN+ASH = Bounce Back Now plus Adult Self Help.

Changes between Baseline and 12-Month Post-Baseline Interviews

Table 2 provides the means and standard deviations for all outcome variables at each measurement point. GEE results for the primary outcomes are presented in Table 3. Tobacco use and binge drinking baserates across all time points were too low to permit a satisfactorily powered comparison between intervention conditions; descriptive statistics for both are reported in Table 4. There was a significant time × condition interaction for PTSD (B=−0.24, SE=0.08, p<.01) and depressive symptoms (B=−0.23, SE=0.09, p<.01), indicating that the intervention conditions differed at one or more post-intervention time points. Post-hoc comparisons between the conditions at each time point suggested no significant difference in PTSD symptoms between the experimental and control groups 4-months post-baseline (B=−0.08, SE=0.17, p=.65). The difference in PTSD symptoms at the 12-month post-baseline interview was marginally significant and suggested that adolescents in the experimental conditions had fewer PTSD symptoms than those in the control condition (B=−0.36, SE=0.19, p=.06). A closer examination of the model-implied means and 95% CIs at 12-month follow-up revealed that the 95% CI for the experimental conditions (M=1.06, 95% CI:0.85–1.33) and control condition (M=1.52, 95% CI:1.12–2.05) did not include the means of the other condition. This lack of overlap provides additional support for a meaningful difference in PTSD symptoms at 12-month post-baseline between the conditions. For depressive symptoms, there was no significant difference between conditions at the 4-month post-baseline interview (B=0.05, SE=0.17, p=.79). However, there was a significant difference between the groups at the 12-month post-baseline interview (B=−0.42, SE=0.19, p=0.03) such that adolescents in the experimental conditions (M=0.58, 95% CI:0.46–0.74) had significantly fewer symptoms than those in the control condition (M=0.89, 95% CI:0.66–1.20). There was no significant difference between groups when comparing alcohol use for the control versus combined active treatment conditions (interaction effect: B=−0.31, SE=0.36, p=.38).

Table 2.

Means and SD at each time point for the three treatment conditions.

| Pretreatment | 4-Month Post-Baseline | 12-Month Post-Baseline | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| BBN (n = 364) |

BBN+ASH (n = 366) |

Control (n = 257) |

BBN (n = 231) |

BBN+ASH (n = 249) |

Control (n = 174) |

BBN (n = 178) |

BBN+ASH (n = 193) |

Control (n = 144) |

||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| PTSD Symptoms | 2.73 | 3.65 | 2.26 | 3.25 | 2.54 | 3.35 | 1.34 | 2.74 | 1.01 | 2.15 | 1.30 | 2.63 | 1.01 | 2.40 | 1.14 | 2.50 | 1.50 | 2.78 |

| Depression Symptoms | 1.40 | 2.00 | 1.22 | 1.81 | 1.43 | 1.96 | 0.79 | 1.61 | 0.64 | 1.30 | 0.69 | 1.40 | 0.54 | 1.44 | 0.60 | 1.28 | 0.83 | 1.58 |

| Alcohol Use | 0.43 | 3.03 | 0.67 | 4.38 | 1.12 | 9.25 | 0.78 | 5.91 | 0.50 | 4.56 | 0.92 | 9.61 | 0.33 | 1.66 | 0.78 | 4.83 | 1.93 | 12.28 |

Note: BBN = Bounce Back Now intervention; BBN+ASH = Bounce Back Now intervention plus Adult Self Help modules; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Table 3.

Primary outcome analyses comparing experimental to control conditions and the BBN vs. BBN+ASH conditions.

| PTSD | Depression | Alcohol Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Experimental compared to control | ||||||

| Time | −0.20** | 0.06 | −0.22** | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.34 |

| Time * Group | −0.24** | 0.08 | −0.23** | 0.09 | −0.31 | 0.36 |

|

| ||||||

| Self-Help + compared to Self-Help − | ||||||

| Time | −0.59** | 0.10 | −0.51** | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.30 |

| Time * Group | 0.30* | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | −0.10 | 0.36 |

Note: BBN = Bounce Back Now intervention; BBN+ASH = Bounce Back Now intervention plus Adult Self Help modules; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

p < .05

p < .01

Table 4.

Prevalence of tobacco use and binge drinking in the 30 days prior to each assessment.

| Pretreatment | 4-Month Post-Baseline | 12-Month Post-Baseline | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| BBN (n=364) |

BBN+ASH (n=366) |

Control (n=257) |

BBN (n=231) |

BBN+ASH (n=249) |

Control (n=174) |

BBN (n=178) |

BBN+ASH (n=193) |

Control (n=144) |

||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Binge Drinking Episodes | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.13 | 0.43 | 0.15 | 0.50 | 0.07 | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.37 | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.14 | 0.46 | 0.22 | 0.58 |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Tobacco Use | 5.00 | 1.30 | 6.00 | 1.70 | 8.00 | 3.20 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 0.80 | 7.00 | 2.70 | 4.00 | 1.10 | 4.00 | 1.10 | 9.00 | 3.50 |

Note: BBN = Bounce Back Now intervention; BBN+ASH = Bounce Back Now intervention plus Adult Self Help modules.

The effect of disaster exposure on outcomes was explored for all outcomes. A significant association emerged between being present at the time of the tornado and PTSD symptoms (B=.55, SE=0.25, p=0.03). When the interaction was probed, those who were present for the tornado had significantly more PTSD symptoms at 4-month (B=1.33, SE=0.50, p=.01) than those who were not present. The interaction between treatment condition and presence for the tornado was marginally significant (B=−1.20, SE=0.62, p=0.055). Interpreting the interaction suggests that the intervention condition had a protective effect in that those who were in the control condition who were present for the tornado had significantly greater symptoms. No other types of disaster exposure were found to be related to outcomes.

A second set of GEEs compared the two active intervention conditions. For PTSD symptoms, the time × condition interaction was significant (B=0.30, SE=0.12, p=.02), suggesting a difference in PTSD symptoms for the active intervention groups over time. Follow-up comparisons found a significant difference at 12-month post-baseline (B=0.47, SE=0.16, p<.01) suggesting that the BBN+ASH group had significantly higher symptoms than the BBN group. There were no significant time × condition interactions for depressive symptoms and alcohol use indicating similar trajectories over time for the two active intervention groups (depression: B=0.12, SE=0.12, p=.33; alcohol use: B=−0.10, SE=0.36, p=.78).

Among those who met criteria for PTSD at baseline, 21 in the BBN condition, 18 in the BBN+ASH, and 8 in the control condition no longer met criteria at the four month assessment. At the 12-month assessment, 22 in the BBN condition, 11 in the BBN+ASH, and 5 in the control condition did not meet PTSD criteria at the 12-month assessment. Of those who met criteria for depression at baseline, 24 in the BBN condition, 15 in the BBN+ASH, and 8 in the control condition no longer met criteria at the four month assessment. At the 12-month assessment, 20 in the BBN condition, 8 in the BBN+ASH, and 9 in the control condition did not meet depression criteria at the 12-month assessment.

DISCUSSION

The current study tested a scalable, sustainable web-based intervention for adolescents using an innovative, population-based design. Population-based recruitment was used because most disaster victims who develop mental health problems do not receive treatment. A key challenge associated with this recruitment approach is that it results in inclusion of a high percentage of adolescents who do not have clinical need for intervention, which reduces opportunity to detect an intervention effect. Despite this challenge, data relating to the feasibility and efficacy of BBN were encouraging. First, nearly half of the 2,000 disaster-affected families accessed the intervention, suggesting that a web-based approach has potential for meaningful penetration after disasters. Such tools may be helpful in preventing escalation of symptoms for at-risk youth and promoting efficient resource allocation by identifying youth at highest risk who should be directed to more intensive levels of care. Non-completion was lower than in other web-based mental health interventions among adolescent community samples but higher than school-based trials.29 Implementation studies are needed to estimate penetration more precisely. Second, adolescents who received BBN vs. Control had greater benefit relative to PTSD and depressive symptoms. This is encouraging because most adolescents had few symptoms at baseline (i.e., means of only 2.5 PTSD and 1.4 depressive symptoms), which greatly limited the potential to detect benefit. Research in shelters and emergency settings soon after an event is needed to assist in estimating the impact of this approach with adolescents who have higher levels of risk for PTSD and depression. Third, the low baserate for smoking and alcohol use problems produced too little power for analysis and interpretation, but use of the modules was satisfactory and suggests the need for further investigation.

We hypothesized that incorporating self-help content for parents would have incremental value over BBN alone because improvements in parental mental health may be associated with improvements in adolescent mental health.30 However, data supported the opposite conclusion. The complexity of the BBN+ASH condition may have contributed to this finding. Parents assigned to BBN+ASH were given access to 11 intervention components in all: 7 addressing parents’ mental health and 4 addressing adolescents’ mental health. This may have reduced the time parents spent on the site learning strategies to address adolescent mental health relative to parents in the BBN-alone condition, who received content that was focused exclusively on facilitating adolescent mental health recovery.

Several strengths and limitations should be noted. The intervention, target population, and recruitment approach all were major strengths. Few disaster mental health intervention studies have been conducted with adolescents.3,4 Most extant studies did not involve parents, and none examined low-cost, highly sustainable technology-based interventions.3–4 Our large sample size and population-based sampling frame also were significant strengths. There also were several weaknesses. First, most adolescents had low symptom levels at baseline, which limited our ability to estimate impact with high-risk families that may have been most likely to benefit. Recruitment of adolescents and adults from shelters and emergency settings may address these weaknesses in future studies. Second, the system was unable to track objectively adolescents’ time spent using the intervention, which was assessed solely via self-report. Third, although representation of African American adolescents in the sample was satisfactory, sampling occurred in geographic areas with low percentages of Latino youth.

Cost-efficient, scalable, and sustainable solutions are needed to support the capacity of disaster-affected communities to facilitate mental health recovery. Public health interventions targeting adolescents and families are particularly important because little is known about their feasibility and utility. Technology-based interventions have potential to increase access to needed resources because they can be made widely and privately accessible at low cost. Yet, until this time, no such interventions have been evaluated in a randomized controlled trial among adolescents and their families. Much more work is needed to examine the efficacy, effectiveness, and reach of such interventions with high-risk samples. Although a small proportion of disaster-affected families may not have access to technology-based interventions, we balance this with the tremendous potential of a system that can be rapidly adopted after disasters throughout the U.S., and with the recognition that internet access via mobile devices is already high and will continue to grow.

Clinical Guidance.

Technology-based self-help interventions may be beneficial as a first-step approach for adolescents affected by disasters and other traumatic life events.

Population-health interventions available via internet-connected devices may have significant penetration after natural disasters. Adolescents and parents each accessed the study intervention at a high rate. Over one third of adolescents and parents recruited accessed the study intervention, and a high percentage of accessers were repeat visitors to the site.

The inclusion of parent-directed content may be valuable in technology-based interventions targeting adolescents, but impact may be reduced if the intervention is complex or contains too many content areas that go beyond adolescent mental health.

Technology-based stepped-care approaches after disaster should integrate additional screening as well as referral mechanisms to complement self-help interventions used in this context.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grant R01 MH081056 (PI: Ruggiero). This includes a Diversity supplement awarded to TMD. Grant R21 MH086313 (PI: Danielson) also supported some elements of this work. The preparation of this manuscript was supported by NIDA Grant K12DA031794 (PI: Brady; support to JM, ZA) and NIAAA K02AA023239 (PI: Amstadter). All views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funding agency or respective institutions.

The authors thank Tiffany Henderson, PhD, at Abt SRBI and Kyleen Welsh, BA, at MUSC for their valuable contributions. The authors also thank Josh Nissenboim, BA, and his staff at Fuzzco for their contributions toward designing and developing Bounce Back Now.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Clinical trial registration information

Web-based Intervention for Disaster-Affected Youth and Families; http://clinicaltrials.gov; NCT01606514.

Drs. Price and Knapp served as the statistical experts for this research.

Disclosure: Drs. Ruggiero, Price, Adams, Stauffacher, McCauley, Kmett Danielson, Knapp, Hanson, Davidson, Amstadter, Carpenter, Saunders, Kilpatrick, and Resnick report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Furr JM, Comer JS, Edmunds JM, Kendall PC. Disasters and youth: A meta-analytic examination of posttraumatic stress. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:765–780. doi: 10.1037/a0021482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65:207–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfefferbaum B, Sweeton JL, Newman E, et al. Child disaster mental health interventions: Techniques, outcomes, and methodological considerations. Disaster Health. 2014;2:46–57. doi: 10.4161/dish.27534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman E, Pfefferbaum B, Kirlic N, Tett R, Nelson S, Liles B. Meta-analytic review of psychological interventions for child survivors of natural and man-made disasters. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16:462. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0462-z. 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfefferbaum B, Varma V, Nitiema P, Newman E. Universal preventive interventions for children in the context of disasters and terrorism. Ch Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2014;23:363–382. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amstadter AB, Broman-Fulks J, Zinzow H, Ruggiero KJ, Cercone J. Internet-based interventions for traumatic stress-related mental health problems. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:410–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox S, Duggan M. Health online 2013. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project; http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/PIP_HealthOnline.pdf. Accessed February 28, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruggiero KJ, Resnick HS, Acierno R, et al. Internet-based intervention for mental health and substance abuse problems in disaster-affected populations. Behav Ther. 2006;37:190–205. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bickel WK, Christensen DR, Marsch LA. A review of computer-based interventions used in assessment, treatment, and research of drug addiction. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46:4–9. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson T, Stallard P, Velleman S. Computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for the prevention and treatment of depression and anxiety in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clin Ch Fam Psychol Rev. 2010;13:275–290. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Addy S, Ijaz A. April 27, 2011: A Day that Changed Alabama. University of Alabama: Center for Business and Economic Research; Accessed February 1, 2015 at http://cber.cba.ua.edu/pdf/Research%20Brief%20Alabama%20Tornadoes%20Economic%20Impact.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Historic Tornado Outbreak: April 27, 2011. Accessed June 1, 2015 at http://www.srh.noaa.gov/hun/?n=hunsur_2011-04-27_main.

- 13.Wind Science and Engineering Center. A Recommendation for an Enhanced Fujita Scale (EF-Scale) 2004 Accessed June 1, 2015 at http://www.spc.noaa.gov/faq/tornado/ef-ttu.pdf.

- 14.National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Joplin Tornado Survey. 2011 Accessed May 1, 2015 at http://www.crh.noaa.gov/sgf/?n=event_2011may22_survey.

- 15.Ruggiero KJ, Resnick HS, Paul LA, et al. Randomized controlled trial of an Internet-based intervention using random-digit-dial recruitment. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruggiero KJ, Davidson TM, McCauley J, et al. Bounce Back Now! A population-based randomized controlled trial of a web-based intervention with families affected by the 2011 spring tornadoes. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;40:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruggiero KJ, Morris TL, Scotti JR. Treatment for children with posttraumatic stress disorder: Current status and future directions. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2001;8:210–227. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopko DR, Lejuez CW, Ruggiero KJ, Eifert GH. Contemporary behavioral activation treatments for depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23:699–717. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruggiero KJ, Morris TL, Hopko DR, Lejuez CW. Application of behavioral activation treatment for depression to an adolescent with a history of child maltreatment. Clin Case Studies. 2007;6:64–78. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, et al. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: main findings from two randomized trials. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waldron HB, Kaminer Y. On the learning curve: The emerging evidence supporting cognitive-behavioral therapies for adolescent substance abuse. Addiction. 2004;99:93–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00857.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruggiero KJ. Bounce Back Now: An e-health intervention for disaster-affected families. Charleston, SC: 2013. Jun, 26th annual Update in Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, et al. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick HS, Best CL, Schnurr PP. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Courtney KE, Polich J. Binge drinking in young adults: Data, definitions, and determinants. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:142–156. doi: 10.1037/a0014414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. Vol. 998. New York: Wiley; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price M, Yuen E, Davidson TM, Hubel G, Ruggiero KJ. Access and completion of a web-based treatment in a population-based sample of tornado-affected adolescents. Psychol Serv. doi: 10.1037/ser0000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neil AL, Batterham P, Christensen H, Bennett K, Griffiths KM. Predictors of Adherence by Adolescents to a Cognitive Behavior Therapy Website in School and Community-Based Settings. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(1):e6. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wickramaratne P, Gameroff MJ, Pilowsky DJ, et al. Children of depressed mothers 1 year after remission of maternal depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:593–602. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10010032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]