Abstract

Objective:

We compared the effect of clopidogrel plus aspirin vs aspirin alone on functional outcome and quality of life in the Clopidogrel in High-risk Patients with Acute Non-disabling Cerebrovascular Events (CHANCE) trial of aspirin-clopidogrel vs aspirin alone after acute minor stroke or TIA.

Methods:

Participants were assessed at 90 days for functional outcome using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) and quality of life using the EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D). Poor functional outcome was defined as mRS score of 2–6 at 90 days and poor quality of life as EQ-5D index score of 0.5 or less.

Results:

Poor functional outcome occurred in 254 patients (9.9%) in the clopidogrel-aspirin group, as compared with 299 (11.6%) in the aspirin group (p = 0.046). Poor quality of life occurred in 142 (5.5%) in the clopidogrel-aspirin group and in 175 (6.8%) in the aspirin group (p = 0.06). Disabling stroke at 90 days occurred in 166 (6.5%) in the clopidogrel-aspirin group and in 219 (8.5%) in the aspirin group (p = 0.01). In stratified analysis by subsequent stroke, there was no difference in 90-day functional outcome and quality of life between the 2 groups.

Conclusions:

In patients with minor stroke or TIA, the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin appears to be superior to aspirin alone in improving the 90-day functional outcome, and this is consistent with a reduction in the rate of disabling stroke in the dual antiplatelet arm.

Classification of evidence:

This study provides Class II evidence that for patients with acute minor stroke or TIA, clopidogrel plus aspirin compared to aspirin alone improves 90-day functional outcome (absolute reduction of poor outcome 1.70%, 95% confidence interval 0.03%–3.42%).

Minor ischemic stroke and TIA are common and 10%–20% of time may lead to subsequent disabling stroke at 90 days.1–4 Stroke remains the leading cause of adult major disability in China and in the world.5,6 To avoid stroke-related functional disability or physical dependence is one of the goals of stroke therapy. It is unclear if aggressive antiplatelet therapy given within the initial hours of stroke or TIA onset could reduce the risk of subsequent disability and improve quality of life.

The Clopidogrel in High-risk Patients with Acute Non-disabling Cerebrovascular Events (CHANCE) trial was designed to test the hypothesis that treatment with clopidogrel plus aspirin reduces the risk of recurrent ischemic stroke compared to aspirin alone in patients with acute high-risk TIA or minor ischemic stroke followed for 90 days.7 The trial found that stroke occurred in 8.2% of patients in the clopidogrel-aspirin group and 11.7% of patients in the aspirin alone group (hazard ratio 0.68; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.57–0.81; p < 0.001).8

In the CHANCE trial, our aim is to compare the effect of clopidogrel plus aspirin vs aspirin alone on prespecified 90-day functional outcome measured by modified Rankin Scale (mRS) and quality of life measured by EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D).

METHODS

Study design.

Details about the CHANCE study rationale, design, and result have been published elsewhere.7,8 Briefly, CHANCE was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted at 114 clinical centers in China. Between October 2009 and July 2012, within 24 hours after the onset of minor ischemic stroke or high-risk TIA, 5,170 patients were randomly assigned to either clopidogrel plus aspirin (clopidogrel at an initial dose of 300 mg, followed by 75 mg per day for 90 days, plus aspirin at a dose of 75 mg per day for the first 21 days) or placebo plus aspirin (75 mg per day for 90 days) group.

Study subjects.

The CHANCE trial recruited 5,170 eligible patients who met the following inclusion criteria: age 40 years or older; diagnosis of an acute minor ischemic stroke (NIH Stroke Scale9 [NIHSS] ≤ 3) or high-risk TIA (ABCD2 ≥ 4)10; and ability to start the study drug within 24 hours after symptom onset. Patients with preexisting disabling conditions defined as mRS11 score of >2 were excluded. For this prespecified outcome measure, 5,131 patients were included after excluding 38 patients with no mRS assessment at 90-day assessment and 1 patient with mRS of 3 at randomization.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The trial was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Tiantan Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants or their legal proxies. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (registration number NCT00979589).

Data collection.

Baseline evaluation included patient demographic information, symptoms of the index event, pretreatment mRS, medications, vascular risk factors, examination findings, and laboratory tests. Vascular risk factors analyzed included history of stroke or TIA, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, angina or congestive heart failure, current or previous smoking, and moderate or heavy alcohol consumption (≥2 standardized alcohol drinks per day). Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg, any use of antihypertensive drug, or self-reported history of hypertension. Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose concentration ≥7.0 mmol/L, nonfasting glucose concentration ≥11.1 mmol/L with classic symptoms of hyperglycemia or hyperglycemic crisis, any use of glucose-lowering drugs, or any self-reported history of diabetes. Dyslipidemia was defined as serum triglyceride ≥150 mg/dL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥130 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≤40 mg/dL, any use of lipid-lowering drugs, or any self-reported history of dyslipidemia.

Outcome assessment.

All investigators and coordinators completed training modules on NIHSS, mRS, and EQ-5D, and were certified. Patients were evaluated by certified investigators who were blinded to patients' clinical status and treatment allocation. The functional outcome and quality of life were assessed at 90 days. The 90-day follow-up was done by face-to-face visit. Severity of functional outcome was measured by mRS (scores range from 0 [no symptoms] to 6 [death]) at 90 days. The primary outcome was dependence or death, defined as mRS of 2–6.

Quality of life was evaluated with the EQ-5D12 assessment, which included domains in mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression. Each dimension was divided into 3 categories12: no problem, moderate problem, or extreme problem. Score of EQ-5D index (preference-based health status) was also calculated based on 5 dimensions of EQ-5D using US preference weights developed by Shaw et al.13 A score of 0 represented death. Poor quality of life was defined as EQ-5D index score of 0.5 or less according to results of the Factor 7 for Acute Hemorrhagic Stroke (FAST) Trial.14

All reported stroke events were verified by a central adjudication committee that was blinded to the study group assignments. We also compared ordinal stroke severity of 2 treatment groups, that is, 3-level ordinal stroke scale with stroke ordered by its severity using mRS at 90 days: no stroke, nondisabling stroke (mRS 0–1), or disabling stroke including fatal stroke (mRS 2–6).

Statistical analysis.

Continuous variables were expressed as median with interquartile range while categorical data were presented as proportions. We compared baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in 2 study groups using the χ2 and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

The difference in rate of poor functional outcome or quality of life between 2 treatment groups was compared by the χ2 test among eligible participants. We also performed the nonparametric test to see if there was a difference in the original mRS (0–6) as an ordinal variable between treatment and control groups. Meanwhile, we built the ordinal logistic regression model with the aspirin group as reference to test whether patients on clopidogrel and those on aspirin had the same mRS scores by grouping mRS into 3 levels (0–2, 3–4, and 5–6). With regard to quality of life, we made exploratory analysis for comparing differences in each of 5 EQ-5D domains (mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression) by using the χ2 test. We also made overall comparison on rate of 3-level ordinal stroke scale (no stroke, nondisabling stroke, and disabling stroke) between 2 treatment groups using the χ2 test and further looked at these 2 contrasts with Bonferroni correction (no stroke vs nondisabling stroke, no stroke vs disabling stroke). The reason for stratified analysis by stroke was to determine whether better outcomes in functional status or quality of life were due to reduction in stroke as reported in main chance results.

We further explored the effect of combined therapy on functional outcome and quality of life among all patients stratified by whether subsequent stroke occurs or not, using a logistic regression model with adjustment for baseline variables remaining imbalanced between 2 groups. All analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.2 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Two-tailed p values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Classification of evidence.

The primary research question was whether clopidogrel plus aspirin vs aspirin alone could improve the functional outcome measured by the mRS score at 90 days in patients with acute minor ischemic stroke or TIA. This study provides Class II evidence that for patients with acute minor stroke or TIA, clopidogrel plus aspirin compared to aspirin alone improves 90-day functional outcome.

RESULTS

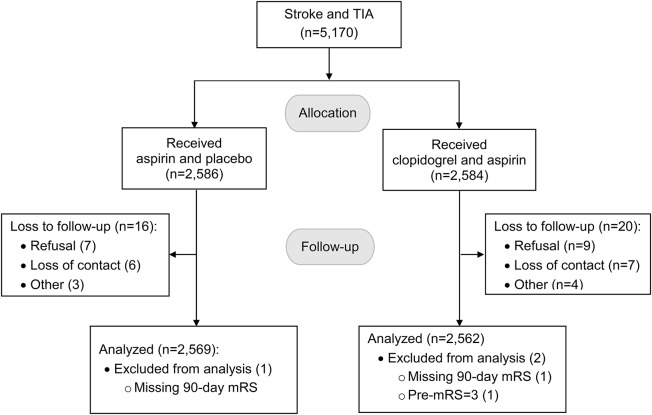

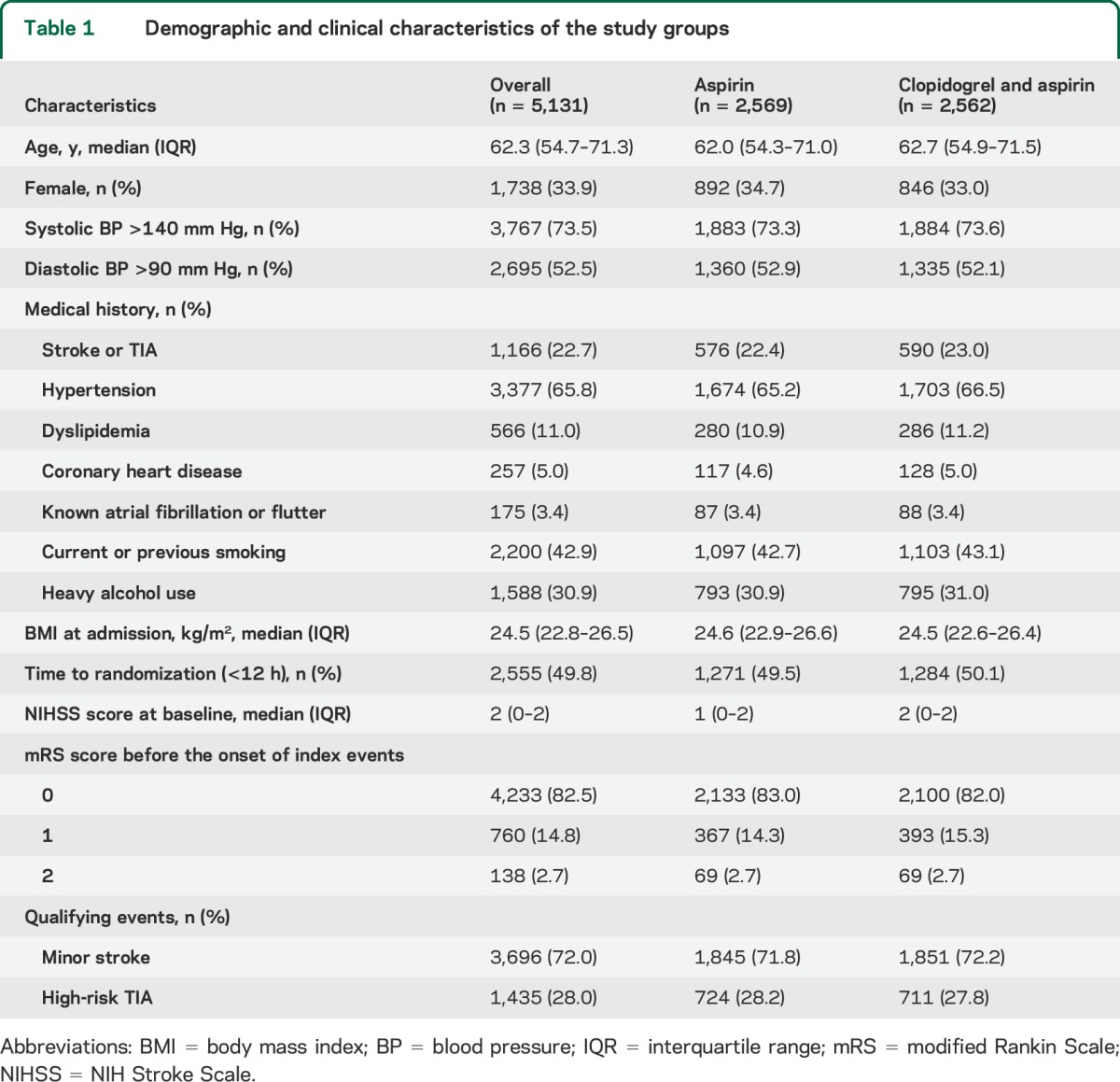

A total of 5,131 patients were included in the final analysis after 39 were excluded due to lack of mRS scores at 90-day follow-up or mRS of >2 at randomization (figure 1). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, including baseline mRS and NIHSS scores, did not differ between the 2 treatment groups (table 1).

Figure 1. Patient flowchart.

mRS = modified Rankin Scale.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study groups

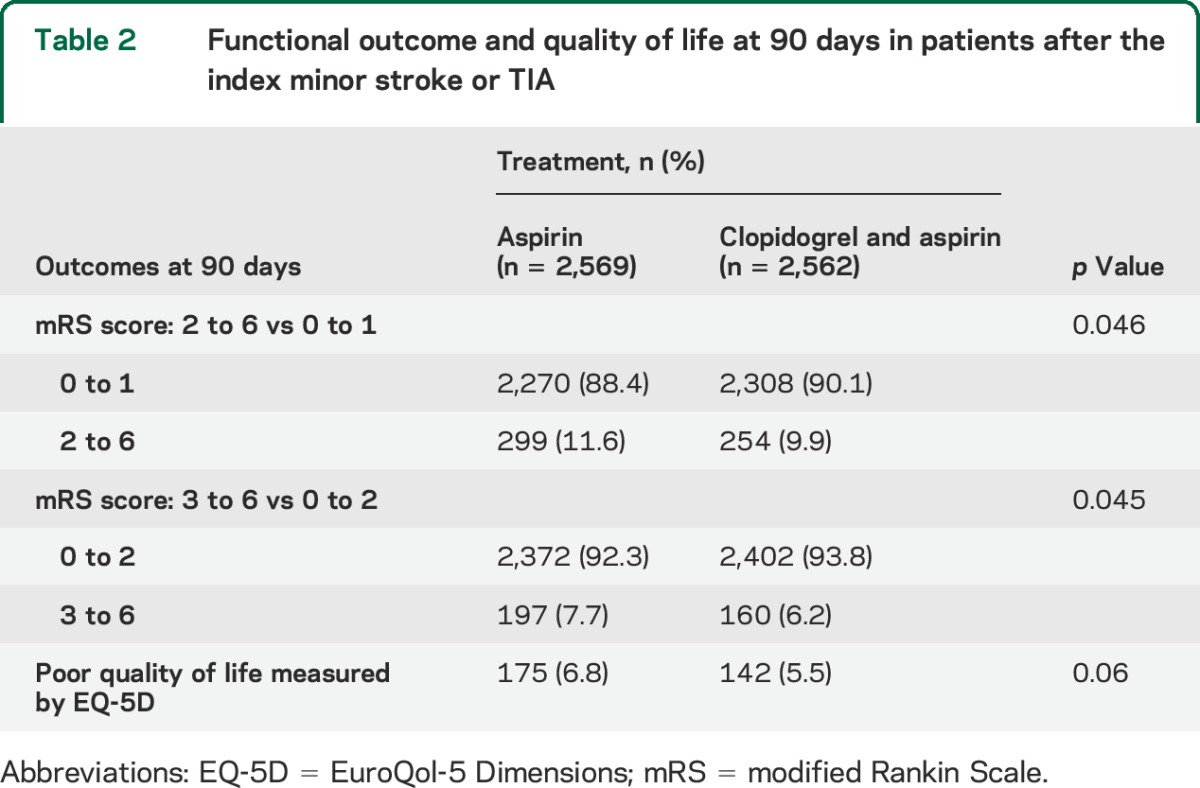

Poor functional outcome (mRS of 2–6) at 90 days occurred in 254 patients (9.9%) in the clopidogrel-aspirin group, as compared with 299 patients (11.6%) in the aspirin group (absolute difference of poor outcome, 1.70%; 95% CI 0.03%–3.42%; p = 0.046); the number needed to treat to avoid a functional disability over 90 days is 59. An mRS of 3–6 at 90-day assessment occurred in 160 patients (6.2%) in the clopidogrel-aspirin group, and in 197 patients (7.7%) in the aspirin group (p = 0.045) (table 2). The ordinal logistic regression analysis also suggested that patients with clopidogrel were more likely to have lower mRS scores than those on aspirin (odds ratio [OR] 1.24; 95% CI 1.002–1.544; p = 0.048). Wilcoxon 2-sample test showed that there was no difference (p = 0.95) in the original mRS (0–6) as an ordinal variable. Distribution of patients at each value of 90-day mRS among 2 study groups is presented in table e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org. Poor quality of life at 90 days occurred in 142 patients (5.5%) in the clopidogrel-aspirin group and in 175 (6.8%) in the aspirin group (p = 0.06) (table 2).

Table 2.

Functional outcome and quality of life at 90 days in patients after the index minor stroke or TIA

Approximately 85% of patients in each of the 2 study groups reported no problems for each item of EQ-5D (figure e-1). However, in dimensions of mobility or activities, proportions of patients with extreme problems in the clopidogrel-aspirin group tended to be lower than in the aspirin group (mobility, 4.4% vs 6.0%, p = 0.05; self-care, 5.2% vs 6.2%, p = 0.08; usual activities, 4.7% vs 6.2%, p = 0.07) (figure e-1).

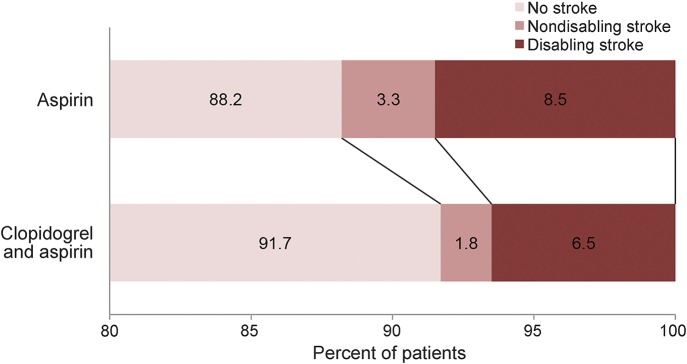

Of 5,131 patients in the trial, 515 patients experienced a new stroke during 90-day follow-up (130 nondisabling stroke and 385 disabling stroke). No stroke occurred in 2,350 patients (91.7%), nondisabling stroke in 46 (1.8%), and disabling stroke in 166 (6.5%) in the clopidogrel-aspirin group, vs no stroke in 2,266 (88.2%), nondisabling stroke in 84 (3.3%), and disabling stroke in 219 (8.5%) in the aspirin group (overall p < 0.001). There were also differences between 2 study groups for disabling stroke vs no stroke (p = 0.01) and for nondisabling stroke vs no stroke (p = 0.001), but no difference for disabling stroke vs nondisabling stroke (p = 0.36) (figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of 3-level ordinal stroke scale by treatment regimen in TIA or minor stroke patients.

There were differences with the Bonferroni adjustment between 2 study groups for disabling stroke vs no stroke (p = 0.01) and for nondisabling stroke vs no stroke (p = 0.001).

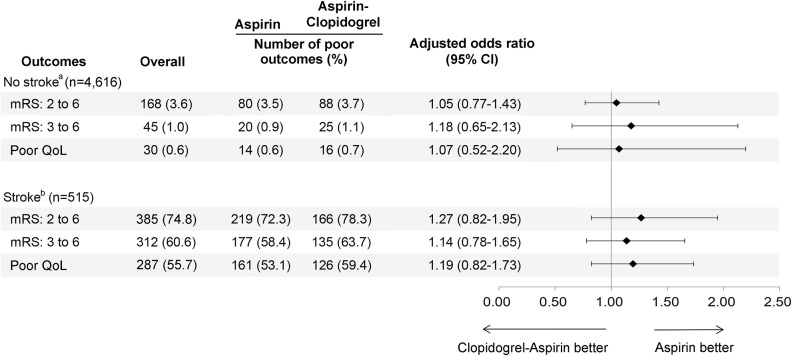

Adjusted ORs in 2 subgroups stratified by stroke are reported in figure 3. Among patients with no stroke at 90 days (n = 4,616), there were no differences between 2 study groups in 90-day mRS of 2–6 (adjusted OR 1.05; 95% CI 0.77–1.43; p = 0.77), in 90-day mRS of 3–6 (adjusted OR 1.18; 95% CI 0.65–2.13; p = 0.59), or in poor quality of life (adjusted OR 1.07; 95% CI 0.52–2.20; p = 0.86), after the adjustment of baseline age remaining unbalanced in 2 study groups (upper part of figure 3 and table e-2). Among patients with a stroke during follow-up (n = 515), there were also no differences between 2 study groups in 90-day mRS of 2–6 (adjusted OR 1.27; 95% CI 0.82–1.95; p = 0.28), in 90-day mRS of 3–6 (adjusted OR 1.14; 95% CI 0.78–1.65; p = 0.50), or in poor quality of life (adjusted OR 1.19; 95% CI 0.82–1.73; p = 0.35), after the adjustment of NIHSS on admission, diastolic blood pressure (>90 mm Hg), and previous dyslipidemia due to baseline unbalance in 2 groups (lower part of figure 3 and table e-3).

Figure 3. Adjusted odds ratios for poor functional outcome and quality of life among patients with subsequent stroke or not.

Patients were stratified by whether subsequent stroke occurred or not at 90 days. CI = confidence interval; mRS = modified Rankin Scale; QoL = quality of life measured by EuroQol-5 Dimensions. aAdjusted for baseline age remaining unbalanced in 2 study groups. bAdjusted for NIH Stroke Scale score on admission, diastolic blood pressure (>90 mm Hg), and previous dyslipidemia due to baseline unbalance in 2 study groups.

DISCUSSION

In the large-scale CHANCE trial involving patients with acute minor ischemic stroke or high-risk TIAs, we found that the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin appeared to improve poor functional outcome at 90 days compared to aspirin, and this was consistent with a reduction in rate of disabling stroke in the dual antiplatelet arm. The rate of disability or death at 90 days was high, and clopidogrel was associated with 1.7% absolute reduction of poor functional outcome, which is equivalent to a number needed to treat of 59 patients to prevent a functional disability. Stratified analysis by stroke showed that there was no difference between 2 treatment groups in functional outcome and quality of life between 2 subgroups of no stroke or stroke.

Our data showed that clopidogrel plus aspirin reduced the absolute proportion of poor functional outcome (mRS of 2–6) by 1.7% when compared with those on aspirin alone. The proportion of patients in the dimensions of mobility and activities associated with quality of life was also lower in the clopidogrel-aspirin group. This might be achieved through an absolute risk reduction of 3.5% for subsequent stroke, especially for disabling stroke (figure 2). Furthermore, of patients experiencing subsequent stroke, approximately three-quarters were disabled or died (mRS of 2–6), while 3.6% of the patients without strokes had this poor outcome (figure 3). Thus, the majority of strokes in the short term after minor stroke or TIA are disabling and the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin might lower this risk. With regard to more aggressive inhibition of platelet aggression for improving stroke disability, the ongoing Triple Antiplatelets for Reducing Dependency After Ischaemic Stroke (TARDIS) trial will determine whether triple antiplatelet strategy will be superior to dual antiplatelet therapy for reducing functional disability and dependence in patients with high risk of stroke.15

Nonparametric analysis in the original mRS did not show statistical difference in the functional outcome between 2 study groups but χ2 analysis in the categorical mRS did; the reason for the difference in results between the ordinal mRS and the categorical mRS might be the unbalanced distribution of patients in each value of mRS (table e-1). With regard to mRS as an ordinal or a categorical variable, which one has more power or whether they have equivalent power would be dependent on the pattern of treatment effect of intervention.16 However, it might not be easy to determine patterns of clinical improvement, because real trials will generally show less pure patterns of response. Thus, given the unbalanced distribution of patients in each value of mRS and characteristics of the target population in this trial, the dichotomized mRS for this study might be a more appropriate approach than the ordinal mRS.

Additionally, we did not find that combination of clopidogrel and aspirin was superior to aspirin alone in improving poor functional outcome and quality of life in stratified analysis by whether subsequent stroke occurred or not at 90 days. Two interpretations for this stratified result are as follows: first, there might not be a direct effect of combined therapy regimen in improving quality of life and lowering rates of functional impairment beyond that aforementioned mediator of the regimen (reducing risk of disabling stroke); second, dual antiplatelet therapy also might not make recurrent stroke less disabling, as compared with monotherapy. However, the result of exploratory analysis should be further validated in future trials with similar biological coherence.

This study has several limitations. It was an analysis on a secondary outcome rather than primary aim of CHANCE trial, so the results might be susceptible to type I error and need to be further confirmed in an independent trial. Second, our findings may not apply to other stroke populations who may have greater frequency of extracranial large-artery atherosclerosis or fewer poor metabolizers of clopidogrel.17 Third, the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin was only given for the first 21 days and longer duration treatment requires further study.18 Fourth, all outcomes in the trial were at 90 days and differences in the treatment groups may not persist long term. Finally, the availability of rehabilitation and the long-term support of stroke patients in China may affect quality of life and rates of disability differently than in other countries.

Our study shows that among patients with minor stroke or high-risk TIA who can be treated within 24 hours after onset of symptoms, the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin appears to be superior to aspirin alone in improving poor functional outcome measured by mRS 90 days after the initial event, and this is consistent with a reduction in the rate of disabling stroke in the dual antiplatelet arm. Together with its overall impact on stroke risk, this reinforces the evidence supporting its use.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank all participating investigators.

GLOSSARY

- CHANCE

Clopidogrel in High-risk Patients with Acute Non-disabling Cerebrovascular Events

- CI

confidence interval

- EQ-5D

EuroQol-5 Dimension

- mRS

modified Rankin Scale

- NIHSS

NIH Stroke Scale

- OR

odds ratio

Footnotes

Editorial, page 562

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yongjun Wang, S. Claiborne Johnston, Yilong Wang, X.Q. Zhao, and C.X. Wang conceived and designed the study. X.W. Wang and Yilong Wang interpreted analysis of the data and prepared the report. Yongjun Wang, S. Claiborne Johnston, Ying Xian, B. Hu, and David Wang contributed to comments on the draft manuscript and revised the report. Yilong Wang and L.P. Liu coordinated the study. Xia Meng, X.W. Wang, and A.X. Wang oversaw subject recruitment and monitored gathering clinical data. B. Hu, H. Li, and J.M. Fang conducted the statistical analysis.

STUDY FUNDING

Supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China. The grant no. is 2008ZX09312-008, 2011BAI08B02, 2012ZX09303, and 200902004.

DISCLOSURE

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kleindorfer D, Panagos P, Pancioli A, et al. Incidence and short-term prognosis of transient ischemic attack in a population-based study. Stroke 2005;36:720–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coull AJ, Lovett JK, Rothwell PM. Population based study of early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke: implications for public education and organisation of services. BMJ 2004;328:326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, Sidney S. Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA 2000;284:2901–2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coutts SB, Modi J, Patel SK, et al. What causes disability after transient ischemic attack and minor stroke? Results from the CT and MRI in the Triage of TIA and minor Cerebrovascular Events to Identify High Risk Patients (CATCH) Study. Stroke 2012;43:3018–3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2197–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang G, Wang Y, Zeng Y, et al. Rapid health transition in China, 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;381:1987–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Claiborne Johnston S. Rationale and design of a randomized, double-blind trial comparing the effects of a 3-month clopidogrel-aspirin regimen versus aspirin alone for the treatment of high-risk patients with acute nondisabling cerebrovascular event. Am Heart J 2010;160:380–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med 2013;369:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyden P, Brott T, Tilley B, et al. Improved reliability of the NIH Stroke Scale using video training: NINDS TPA Stroke Study Group. Stroke 1994;25:2220–2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 2007;369:283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, et al. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988;19:604–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med 2001;33:337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaw JW, Johnson JA, Coons SJ. US valuation of the EQ-5D health states: development and testing of the D1 valuation model. Med Care 2005;43:203–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christensen MC, Mayer S, Ferran JM. Quality of life after intracerebral hemorrhage: results of the Factor Seven for Acute Hemorrhagic Stroke (FAST) trial. Stroke 2009;40:1677–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.University of Nottingham. Triple Antiplatelets for Reducing Dependency After Ischaemic Stroke (TARDIS). Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01661322. Accessed July 3, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saver JL, Gornbein J. Treatment effects for which shift or binary analyses are advantageous in acute stroke trials. Neurology 2009;72:1310–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hankey GJ. Dual antiplatelet therapy in acute transient ischemic attack and minor stroke. N Engl J Med 2013;369:82–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. Platelet-oriented inhibition in new TIA and minor ischemic stroke (POINT) trial: rationale and design. Int J Stroke 2013;8:479–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.