Abstract

Introduction

Theoretic models suggest that associations between substance use and dating violence perpetration may vary in different social contexts, but few studies have examined this proposition. The current study examined whether social control and violence in the neighborhood, peer, and family contexts moderate the associations between substance use (heavy alcohol use, marijuana, and hard drug use) and adolescent physical dating violence perpetration.

Methods

Adolescents in the eighth, ninth, and tenth grades completed questionnaires in 2004 and again four more times until 2007 when they were in the tenth, 11th and 12th grades. Multilevel analysis was used to examine interactions between each substance and measures of neighborhood, peer, and family social control and violence as within-person (time-varying) predictors of physical dating violence perpetration across eighth through 12th grade (N=2,455). Analyses were conducted in 2014.

Results

Physical dating violence perpetration increased at time points when heavy alcohol and hard drug use were elevated; these associations were weaker when neighborhood social control was higher and stronger when family violence was higher. Also, the association between heavy alcohol use and physical dating violence perpetration was weaker when teens had more-prosocial peer networks and stronger when teens’ peers reported more physical dating violence.

Conclusions

Linkages between substance use and physical dating violence perpetration depend on substance use type and levels of contextual violence and social control. Prevention programs that address substance use–related dating violence should consider the role of social contextual variables that may condition risk by influencing adolescents’ aggression propensity.

Introduction

Physical dating violence perpetration (PDVP), which is the use of physical violence against a dating partner during adolescence, is a prevalent national problem1 that can result in devastating consequences.2 One risk factor that has been consistently linked to adult3–13 and adolescent14–20 partner violence is substance use. The predominant explanation for this linkage is that psychopharmacologic effects impair cognition and disinhibit aggression.10,11 However, many individuals who engage in substance use do so without engaging in partner violence, suggesting other factors may play a role in conditioning their association.4,5,10,11 This notion is consistent with numerous theoretic “interaction” models that suggest the effects of substance use on PDVP will vary depending on characteristics of the individual and their social context.21–25 Some research with adults supports this proposition21,26–33; however, few studies have examined moderators of the linkage between substance use and adolescent PDVP. A better understanding of the contextual factors that condition associations between substance use and PDVP could inform primary prevention efforts that go beyond focusing exclusively on individual risk factors to changing the social contexts that influence risk for substance-related PDVP. To this end, the current longitudinal study examined whether indicators of violence exposure and social control drawn from family, peer, and neighborhood environments, three critical social contexts that influence adolescent development, moderated associations between substance use (heavy alcohol use [HALC], marijuana use [MAR], and hard drug use [HDRG]) and PDVP across eighth through 12th grade.

Empirical studies with adults suggest that substance use works synergistically with other aggression-provoking factors to predict the use of partner violence.21,26–33 These findings are consistent with theoretic models that propose that substance use will more likely lead to partner violence among individuals with greater propensity for aggression.21,25 The basic reasoning underlying these models posits that individuals vary in their aggression threshold, which is the point at which the strength of aggressive motivation exceeds the strength of aggressive inhibitions; when the threshold is exceeded, violent behavior results. Substance use intoxication may lower the threshold by impairing cognitive function. Intoxication will thus be more likely to lead to partner violence among individuals with increased aggression propensity because they already have low thresholds, even in the absence of intoxication.5,21,25 Conversely, this reasoning suggests that substance use may be less likely to lead to partner violence among individuals with high aggression thresholds (e.g., owing to strong inhibitions against the use of aggression) because intoxication will not lower the threshold enough for violence to occur.

Contextual social control and violence are aspects of adolescents’ social environments that may influence aggression propensity and thus moderate associations between substance use and PDVP. Contexts (i.e., neighborhoods, peer groups, families) that promote social control may increase constraints or inhibitions against aggressive behavior, producing a higher aggression threshold, through social regulation of deviant behavior and by encouraging conformity to prosocial values and norms, including antiviolence and social responsibility norms.34,35 As such, the effects of substance use on PDVP may be weaker among adolescents nested in social environments with higher levels of social control (e.g., higher levels of parent monitoring) because these controls establish a higher aggression threshold.

Exposure to violence in different contexts may also influence aggression propensity and thus moderate the influence of substance use on PDVP. In particular, elevated levels of contextual violence may increase adolescent propensity for aggression (and thus lower aggression thresholds) by making it more likely that youth access aggressive scripts and schemas as guides for behavior or by increasing negative affect.36–40 Increased propensity for aggression that results from violence exposure (e.g., family violence exposure) may work synergistically with substance use to increase risk for PDVP.

The Current Study

The current study aims to determine whether and how indicators of contextual social control and violence moderate associations between HALC, MAR, and HDRG and PDVP. The overarching hypotheses are that associations between substance use and PDVP will be weaker when contextual social control is elevated and stronger when contextual violence is elevated. Hypotheses are tested with longitudinal data using an analytic strategy focused on within-person changes in substance use in relation to within-person changes in PDVP; this approach allows for determining if PDVP increases at time points when substance use is elevated, an expectation based on the psychopharmacologic effects model of substance use on PDVP, and whether that effect is moderated by changes in contextual social control or violence.41 The potential for sex differences in moderated effects is also explored based on work suggesting that associations between substance use and PDVP may differ for boys and girls.16–18

Few studies have examined contextual moderators of the association between substance use and PDVP. The only study to examine social control as a contextual moderator found that neighborhood collective efficacy, defined as community social cohesion and willingness to intervene for the common good, did not moderate the association between a composite measure of substance use and PDVP assessed 6 years later42; however, that study did not distinguish among specific substances, and focused on the distal effects of early substance use on later PDVP. Previous research using the same data source as the current study found that the association between HALC and PDVP was moderated by family and peer violence, but not neighborhood violence. However, that study did not control for or examine interactions with other substances or examine measures of contextual social control as potential moderators.39 The current study addresses these limitations and builds on this previous work by simultaneously examining interactions between indicators of contextual social control and violence and the unique effects of three substance use behaviors (HALC, MAR, and HDRG) as predictors of PDVP.

Methods

Data were from a multi-wave study of adolescent health.43,44 Participants were enrolled in public school systems located in two counties. Four waves of data were collected beginning when adolescents were in eighth to tenth grades (2003) and continuing until they were in tenth to 12th grade (2005). Six-month time intervals separated the first three waves and a 1-year interval separated the last two waves. Parents could refuse consent for their child’s participation by returning a form or via a toll-free telephone number. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Public Health IRB approved study protocols.

Study Sample

Of the 3,343 students eligible for participation at Wave 1 (W1), 2,636 (79%) completed a questionnaire. Analyses excluded respondents who were missing data on race (n=40), dating status (n=67), or PDVP (n=74) across all waves, yielding an analytic sample size of 2,455. Nearly all students contributed at least two waves of data (n=2,299, 94%), with 78% participating in three or more waves (n=1,920). The analytic sample was 47% black, 48% were male, and 40% reported that the highest education obtained by either parent was high school or less. Table 1 presents W1 sample characteristics and descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Wave 1 (n=2,455)

| % | M [SD] | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 48 | -- |

| Female | 52 | -- |

| Race | ||

| White | 43 | -- |

| Black | 47 | -- |

| Other race ethnicity | 10 | -- |

| Parent education | ||

| Less than high school | 10 | |

| High school graduate | 30 | |

| More than high school | 60 | |

| Grade | ||

| 8 | 35 | -- |

| 9 | 34 | -- |

| 10 | 31 | -- |

| Past three month substance use | ||

| Heavy alcohol use | 18 | 0.25 [0.74] |

| Marijuana use | 21 | 0.50 [1.14] |

| Hard drug use | 4 | -- |

| Past three month physical dating violence perpetration | 15 | 0.62 [2.43] |

| Contextual social control | ||

| Neighborhood control | -- | 2.70 [1.02] |

| Peer control | -- | 2.93 [0.40] |

| Family control | -- | 2.11 [0.85] |

| Contextual violence | ||

| Neighborhood violence | -- | 1.13 [1.04] |

| Peer dating violence | -- | 0.46 [0.66] |

| Family violence | -- | 1.14 [1.23] |

Note: Means (M) and SD are based on scale scores; percentages (%) for substance use and physical dating violence perpetration denote proportion of sample reporting any past three month involvement in the behavior.

Measures

To assess physical dating violence perpetration, adolescents were asked: During the past 3 months, how many times did you do each of the following things to someone you were dating or on a date with? Don’t count it if you did it in self-defense or play. Six items listing physically violent behavioral acts were listed (e.g., hit or slapped them). Response options ranged from never (0) to ten or more times (4). Scores were summed to create a composite (Cronbach’s α=0.93).

All substance use measures used a past 3–month reference period with response options that ranged from never (0) to ten or more times (3). HALC was measured by averaging four items assessing how many times respondents had: three or four drinks in a row, five or more drinks in a row, gotten drunk from drinking alcohol, or been hung over (α=0.95). MAR was assessed by asking respondents how often they had engaged in MAR. HDRG was assessed by asking how often respondents had engaged in other hard drug use (cocaine, LSD, heroin, ecstasy, or other); owing to low prevalence (4% at W1), responses were dichotomized to denote whether the respondent had (1) or had not (0) used hard drugs in the past 3 months.

Family control was measured by averaging three items (α=0.76) assessing the respondent’s report of parent rule setting and monitoring (e.g., he/she has rules that I must follow). Using a directory of enrolled students, adolescents were asked to identify up to five of their closest friends. Peer control was measured via two scales assessing the extent to which the respondents’ nominated friends endorsed conventional beliefs (three items; e.g., it’s good to be honest) and prosocial values (three items; e.g., it’s important to finish high school); scores were averaged to create a composite measure (standardized α=0.75). Neighborhood control was measured by averaging five items (α=0.80) assessing respondents’ perceptions of neighborhood social cohesion, adult monitoring of youth, and willingness to intervene to prevent deviance.

Family violence was measured by averaging three items (α=0.87) from Bloom’s family functioning scale (e.g., family members sometimes hit each other).45 Neighborhood violence was measured by averaging three items (α=0.87) assessing perceptions of violence and safety in their neighborhood (e.g., people there have violent arguments). Peer dating violence was measured by summing the number of nominated friends who reported any PDVP.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed in 2014. Data were reorganized by grade (rather than wave) and multilevel analysis (using SAS, version 9.3) was used to examine the within-person (time-varying) effects of substance use, contextual moderators, and their interactions on levels of PDVP (logged) across eighth through 12th grades. The best-fitting unconditional trajectory model of PDVP included both linear (grade) and quadratic (grade2) fixed effects for grade-level, heteroscedastic errors, and a random intercept. Following standard recommendations for examining within-person effects of time-varying covariates, all substance use and contextual moderator variables were person-mean centered.46 Models controlled for the linear and quadratic effects of grade, sex, race/ethnicity, parent education, and dating abuse victimization (i.e., experiencing any dating violence in the previous 3 months). Multiple imputation (20 imputations) using SAS PROC MI/MIANALYZE was used to address missing data.47

A series of conditional multilevel models were estimated to test hypotheses. First, a baseline model was estimated that included the time-varying (“main”) effects of each substance use type and contextual moderator as well as controls. Next, sets of two- and three-way interactions among HALC, the contextual moderators, and sex were added to the baseline model and the joint significance of the contribution of each set of interactions to the model was evaluated using a multiparameter Wald test, which was set at a Bonferroni-corrected value of 0.002 (α=0.05/9 sets of interactions). Individual significant (p<0.05) interactions within each set of interactions that contributed significantly to the model were retained. This model reduction procedure was repeated for examining interactions involving MAR and HDRG. Significant individual interactions were probed by producing model-estimated simple slopes denoting the association between the focal substance use variable and PDVP at high (+1 SD above the mean) and low (−1 SD below the mean) levels of the moderator variable.48

Results

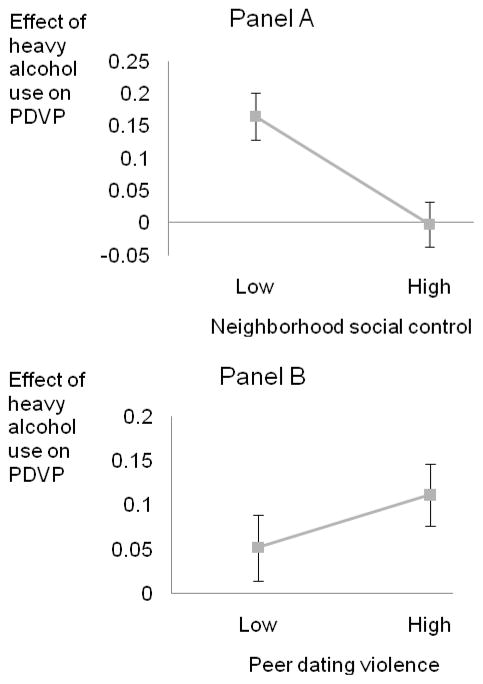

Table 2 presents results from the reduced models. The final HALC model (Column 1) retained significant interactions with neighborhood control (p<0.001), peer control (p=0.02), peer dating violence (p=0.01), and family violence (p=0.003). Simple slopes analyses found that, as expected, neighborhood and peer control buffered the effects of HALC on PDVP (Figure 1, Panels A and C). Increased HALC was not associated with increased PDVP when neighborhood control was high (p=0.85), but was associated with PDVP when it was low (coefficient=0.17, p<0.001). HALC was positively related to PDVP when peer control was both high and low; however, associations were significantly weaker when peer control was high (coefficient=0.05, p=0.01) compared with when it was low (coefficient=0.11, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Contextual Moderators of Longitudinal Within-Person Associations Between Substance Use and Physical Dating Violence Perpetration

| Heavy alcohol use interactions | Marijuana use interactions | Hard drug use interactions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (se) | p | b (se) | p | b (se) | p | |

| Main Effects | ||||||

| Heavy alcohol use (HALC) | 0.08 (0.01) | <0.001 | 0.10 (0.01) | <0.001 | 0.09 (0.01) | <0.001 |

| Marijuana use (MAR) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.05 | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.05 | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.11 |

| Hard drug use (HDRG) | 0.45 (0.04) | <0.001 | 0.48 (0.04) | <0.001 | 0.10 (0.06) | 0.13 |

| Neighborhood control | −0.02 (0.01) | 0.01 | −0.03 (0.01) | 0.003 | −0.02 (0.01) | 0.01 |

| Peer control | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.57 | −0.02 (0.02) | 0.36 | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.46 |

| Family control | −0.001 (0.01) | 0.93 | −0.004 (0.01) | 0.77 | −0.001 (0.01) | 0.94 |

| Neighborhood violence | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.30 | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.32 | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.38 |

| Peer dating violence | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.14 | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.11 | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.14 |

| Family violence | 0.03 (0.01) | <0.001 | 0.03 (0.01) | <0.001 | 0.03 (0.01) | <0.001 |

| Heavy alcohol use interactions | ||||||

| HALC X Neighborhood control | −0.11 (0.02) | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| HALC X Peer control | −0.08 (0.03) | 0.03 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| HALC X Peer dating violence | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| HALC X Family Violence | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.003 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Marijuana use interactions | ||||||

| MAR X Neighborhood SC | -- | -- | −0.04 (0.01) | <0.001 | -- | -- |

| Hard drug use interactions | ||||||

| HDRG X Male | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.61 (0.08) | <0.001 |

| HDRG X Neighborhood control | -- | -- | -- | -- | −0.29 (0.05) | <0.001 |

| HDRG X Family violence | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.12 (0.04) | 0.01 |

Note: Variables were time-varying and person-mean centered. Models controlled for sex, grade, race, parent education, and dating abuse victimization.

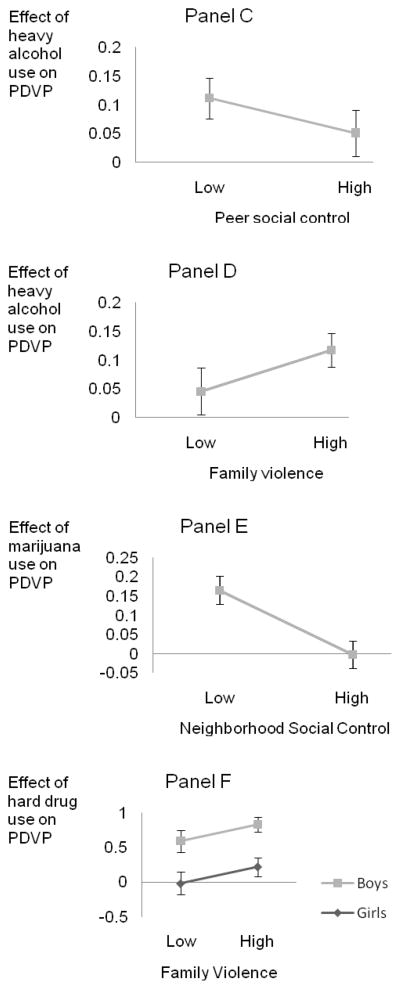

Figure 1.

Parameter estimates and 95% CIs for the within-person effects of heavy alcohol (Panels A–D), marijuana (Panel E) and other hard drug use (Panels F–G) on physical dating violence perpetration (PDVP) at low (−1 std below the mean) and high (+1 std above the mean) levels of contextual social control and violence.

Note: Error bars depict 95% CIs. Effects for hard drug use are depicted separately for boys and girls because there was a significant two-way interaction between hard drug use and sex.

Also as expected, peer dating violence and family violence exacerbated the effects of HALC on PDVP (Figure 1, Panels B and D). Findings replicate those reported previously39 and show that the prior findings are robust to inclusion of controls for other substance use behaviors as well as the contextual social control indicators and their interactions with HALC. Elevated HALC was associated with increased PDVP when peer dating violence was both high and low; however, associations were stronger when peer violence was high (coefficient=0.11, p<0.001) compared with low (coefficient=0.05, p=0.01). Similarly, associations were stronger when family violence was high (coefficient=0.12, p<0.001) compared with low (coefficient=0.05, p=0.04).

The reduced model for MAR (Table 2, Column 2) included one significant interaction with neighborhood control (p<0.001). As expected, neighborhood control buffered the association between MAR and PDVP (Figure 1, Panel E); elevated MAR was not significantly associated with PDVP when neighborhood control was high (p=0.12), but was when it was low (coefficient=0.05, p<0.001).

The reduced model for HDRG (Table 2, column 3) included significant two-way interactions with family violence (p=0.01) and neighborhood control (p<0.001). As expected, family violence exacerbated and neighborhood control buffered the effects of increased HDRG on PDVP. The strength and pattern of these moderating effects was the same for boys and girls (i.e., there was no three-way interaction with sex); however, because there was a significant two-way interaction between HDRG and sex (p<0.001), simple slopes were probed separately for boys and for girls (Figure 1, Panels F and G). Among girls, HDRG and PDVP were not associated when neighborhood control was high (p=0.09), but they were associated when neighborhood control was low (p<0.001); also, the association for girls was significant when family violence was high (p=0.002) but not low (p=0.79). Among boys, associations between HDRG and PDVP were significantly weaker when neighborhood control was high (coefficient=0.49, p<0.001) compared with low (coefficient=0.93, p<0.001), and stronger when family violence was high (coefficient=0.83, p<0.001) compared with low (coefficient=0.59, p<0.001).

Ancillary analyses examined whether findings held when all significant interactions were modeled simultaneously (results not shown). Interactions with HALC and HDRG maintained statistical significance (family violence interactions were marginal); however, the interaction between MAR and neighborhood control became non-significant (p=0.60), thus this finding should be viewed with caution.

Discussion

This study extends previous research that has established a linkage between substance use and PDVP by demonstrating that associations depend on characteristics of the social context in which the adolescent is embedded. In particular, associations between specific substances (HALC, MAR, and HDRG) and PDVP were buffered by neighborhood and peer control and exacerbated by family and peer violence, though findings depended on substance use type.

Associations between all three substances and PDVP were weaker when teens reported higher levels of neighborhood control; associations between HALC and PDVP were also buffered by peer control. Social disorganization perspectives suggest that higher levels of neighborhood control may be associated with exposure to positive conflict resolution models, antiviolence norms, and the availability of prosocial supports and helping resources to teens; these effects, in turn, may lower aggression propensity and strengthen aggressive inhibitions, dampening the effect of substance use on PDVP.43,49–51 Similarly, teens nested in prosocial peer networks may have lower aggression propensity because they are exposed to positive peer models of conflict resolution and believe that using dating violence could harm their peer relationships; this decreased aggression propensity may weaken the influence of HALC on PDVP. Unexpectedly, family control did not moderate associations between any of the substances and PDVP; it may be that increased parental controls do not strengthen adolescent inhibitions against the use of aggression in romantic relationships.

Associations between HALC and PDVP were stronger for teens reporting elevated levels of family and peer violence; family violence also exacerbated associations between HDRG and PDVP. Elevations in family and peer violence may increase aggression propensity, and thus work synergistically with HALC and HDRG to increase PDVP risk, because adolescents draw on family and peer models as immediate sources of information as to how to act when faced with dating conflict or because violence exposure may contribute to negative affect (e.g., anger).38 Unexpectedly, neighborhood violence did not moderate associations between use of the substances and PDVP; interactions with neighborhood control or with the more-proximal violence exposures may have accounted for the moderating effect of neighborhood violence.

Some findings differed by substance use type. The only interaction found for MAR was with neighborhood social control, which was not robust in ancillary analyses. We view this finding with caution, particularly given the inconsistent results of research examining associations between MAR and adult partner violence.10,52–56 It is also notable that peer violence and control only conditioned associations between HALC and PDVP. Perhaps when teens engage in HALC on dates, they are particularly likely to do so in social events where peers are present, enabling them to have a proximal influence on dating conflict.

Together, findings suggest that interventions that increase neighborhood control by fostering interaction among neighbors (e.g., community network–building programs) and establishing informal community social control networks (e.g., via community policing programs) could reduce HALC-, MAR-, and HDRG-related PDVP.57 In addition, violence interventions for teens exposed to family violence should address the link between HALC and HDRG and PDVP. Finally, interventions that promote prosocial values and antiviolence norms in peer networks may be particularly effective in reducing alcohol-related PDVP.

Limitations

The following limitations should be considered. The observational design of the study precludes our ability to make any causal inferences with respect to the associations that were detected. Measures were self-reported and thus subject to social desirability and same-source bias; further, measures were composed of relatively few items, potentially limiting their ability to assess complex multidimensional constructs. In addition, the study examined only three substances and did not examine associations with psychological or sexual violence.

Conclusions

The current study used longitudinal data to examine the dynamic associations between within-individual changes in substance use and PDVP and potential social contextual moderators of these associations. Findings suggest that risk for substance-related adolescent dating violence perpetration may be exacerbated by contextual violence and constrained by contextual social control. Interventions that address substance-related dating violence should consider the role of contextual variables that may condition risk by influencing aggression propensity.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA13459, S Ennett, Principal Investigator [PI]) and CDC (R49CCV423114, V Foshee, PI). Secondary data analysis and manuscript writing was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1R03DA033420-01A1, H Reyes, PI) and by an inter-agency personnel agreement (IPA) between Dr. Reyes and CDC (13IPA130569) and between Dr. Foshee and CDC (13IPA1303570). The conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63(Suppl 4):1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, Rothman E. Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):71–78. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1029. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afifi TO, Henriksen CA, Asmundson GJG, Sareen J. Victimization and perpetration of intimate partner violence and substance use disorders in a nationally representative sample. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200(8):684–691. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182613f64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182613f64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foran HM, O’Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(7):1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klostermann KC, Fals-Stewart W. Intimate partner violence and alcohol use: Exploring the role of drinking in partner violence and its implications for intervention. Aggress Violent Behav. 2006;11(6):587–597. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2005.08.008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraanen FL, Vedel E, Scholing A, Emmelkamp PMG. Prediction of intimate partner violence by type of substance use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014;46(4):532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.10.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Testa M, Derrick JL. A daily process examination of the temporal association between alcohol use and verbal and physical aggression in community couples. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28(1):127–138. doi: 10.1037/a0032988. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0032988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Margolin G, Ramos MC, Baucom BR, Bennett DC, Guran EL. Substance use, aggression perpetration, and victimization: Temporal co-occurrence in college males and females. J Interpers Violence. 2013;28(14):2849–2872. doi: 10.1177/0886260513488683. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260513488683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore TM, Elkins SR, McNulty JK, Kivisto AJ, Handsel VA. Alcohol use and intimate partner violence perpetration among college students: Assessing the temporal association using electronic diary technology. Psychol Violence. 2011;1(4):315–328. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0025077. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore TM, Stuart GL, Meehan JC, Rhatigan DL, Hellmuth JC, Keen SM. Drug abuse and aggression between intimate partners: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(2):247–274. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shorey RC, Stuart GL, Cornelius TL. Dating violence and substance use in college students: A review of the literature. Aggress Violent Behav. 2011;16(6):541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2011.08.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith PH, Homish GG, Leonard KE, Cornelius JR. Intimate partner violence and specific substance use disorders: Findings from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26(2):236–245. doi: 10.1037/a0024855. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0024855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Testa M. The role of substance use in male-to-female physical and sexual violence - A brief review and recommendations for future research. J Interpers Violence. 2004;19(12):1494–1505. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269701. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260504269701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein-Ngo QM, Cunningham RM, Whiteside LK, et al. A daily calendar analysis of substance use and dating violence among high risk urban youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;130(1–3):194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haynie DL, Farhat T, Brooks-Russell A, Wang J, Barbieri B, Iannotti RJ. Dating violence perpetration and victimization among U.S. adolescents: Prevalence, patterns, and associations with health complaints and substance use. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(2):194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reyes HLM, Foshee VA, Bauer DJ, Ennett ST. Proximal and time-varying effects of cigarette, alcohol, marijuana and other hard drug use on adolescent dating aggression. J Adolesc. 2014;37(3):281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.02.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivera-Rivera L, Allen-Leigh B, Rodriguez-Ortega G, Chavez-Ayala R, Lazcano-Ponce E. Prevalence and correlates of adolescent dating violence: Baseline study of a cohort of 7960 male and female mexican public school students. Prev Med. 2007;44(6):477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.02.020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothman EF, Reyes LM, Johnson RM, LaValley M. Does the alcohol make them do it? dating violence perpetration and drinking among youth. Epidemiol Rev. 2012;34(1):103–119. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxr027. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxr027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothman EF, Stuart GL, Winter M, et al. Youth alcohol use and dating abuse victimization and perpetration: A test of the relationships at the daily level in a sample of pediatric emergency department patients who use alcohol. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27(15):2959–2979. doi: 10.1177/0886260512441076. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260512441076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Temple JR, Shorey RC, Fite P, Stuart GL, Vi Donna Le. Substance use as a longitudinal predictor of the perpetration of teen dating violence. J Youth Adoles. 2013;42(4):596–606. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9877-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9877-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fals-Stewart W, Leonard K, Birchler G. The occurrence of male-to-female intimate partner violence on days of men’s drinking: The moderating effects of antisocial personality disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(2):239–248. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finkel EJ. The I-3 model: Metatheory, theory, and evidence. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2014;49:1–104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800052-6.00001-9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leonard KE. U.S. DHHS, editor. Research monograph 24: Alcohol and interpersonal violence: Fostering multidisciplinary perspectives. Rockville, MD: NIH; 1993. Drinking patterns and intoxication in marital violence: Review, critique, and future directions for research; pp. 253–280. NIH Publication No. 93–3496. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clements K, Schumacher JA. Perceptual biases in social cognition as potential moderators of the relationship between alcohol and intimate partner violence: A review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2010;15(5):357–368. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2010.06.004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parker R, Auerhahn K. Alcohol, drugs, and violence. Annu Rev Sociol. 1998;24:291–311. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.291. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cunradi CB. Drinking level, neighborhood social disorder, and mutual intimate partner violence. Alcoholism (NY) 2007;31(6):1012–1019. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00382.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foran HM, O’Leary KD. Problem drinking, jealousy, and anger control: Variables predicting physical aggression against a partner. J Fam Violence. 2008;23(3):141–148. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10896-007-9136-5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levinson CA, Giancola PR, Parrott DJ. Beliefs about aggression moderate alcohol’s effects on aggression. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;19(1):64–74. doi: 10.1037/a0022113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0022113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schumacher JA, Coffey SF, Leonard KE, O’Jile JR, Landy NC. Self-regulation, daily drinking, and partner violence in alcohol treatment-seeking men. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;21(1):17–28. doi: 10.1037/a0031141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0031141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schumacher JA, Homish GG, Leonard KE, Quigley BM, Kearns-Bodkin JN. Longitudinal moderators of the relationship between excessive drinking and intimate partner violence in the early years of marriage. J Fam Psychol. 2008;22(6):894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0013250. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0013250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shorey RC, Stuart GL, Moore TM, McNulty JK. The temporal relationship between alcohol, marijuana, angry affect, and dating violence perpetration: A daily diary study with female college students. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28(2):516–523. doi: 10.1037/a0034648. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0034648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stalans LJ, Ritchie J. Relationship of substance use/abuse with psychological and physical intimate partner violence: Variations across living situations. J Fam Violence. 2008;23(1):9–24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10896-007-9125-8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watkins LE, Maldonado RC, DiLillo D. Hazardous alcohol use and intimate partner aggression among dating couples: The role of impulse control difficulties. Aggressive Behav. 2014;40(4):369–381. doi: 10.1002/ab.21528. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ab.21528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Booth JA, Farrell A, Varano SP. Social control, serious delinquency, and risky behavior. Crime Delinq. 2008;54(3):423–456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0011128707306121. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellis WE, Chung-Hall J, Dumas TM. The role of peer group aggression in predicting adolescent dating violence and relationship quality. J Youth Adolesc. 2013;42(4):487–499. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9797-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9797-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon VA, Furman W. Interparental conflict and adolescents’ romantic relationship conflict. J Res Adolesc. 2010;20(1):188–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00635.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Mueller V, Grych JH. Youth experiences of family violence and teen dating violence perpetration: Cognitive and emotional mediators. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2012;15(1):58–68. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0102-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reyes HLM, Foshee VA, Bauer DJ, Ennett ST. Heavy alcohol use and dating violence perpetration during adolescence: Family, peer and neighborhood violence as moderators. Prev Sci. 2012;13(4):340–349. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0215-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11121-011-0215-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bandura A. Social-learning theory of aggression. J Commun. 1978;28(3):12–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1978.tb01621.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1978.tb01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White HR, Fite P, Pardini D, Mun E, Loeber R. Moderators of the dynamic link between alcohol use and aggressive behavior among adolescent males. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41(2):211–222. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9673-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9673-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schnurr MP, Lohman BJ. The impact of collective efficacy on risks for adolescents’ perpetration of dating violence. J Youth Adolesc. 2013;42(4):518–535. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9909-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9909-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Foshee VA, Reyes HLM, Ennett ST, et al. Risk and protective factors distinguishing profiles of adolescent peer and dating violence perpetration. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(4):344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Hussong A, et al. The peer context of adolescent substance use: Findings from social network analysis. J Res Adolesc. 2006;16(2):159–186. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00127.x. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bloom BL. A factor analysis of Self-Report measures of family functioning. Fam Process. 1985;24(2):225–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1985.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raudenbush Stephen W, Bryk Anthony S. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Vol. 1. Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(2):147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Banyard VL, Cross C, Modecki KL. Interpersonal violence in adolescence: Ecological correlates of self-reported perpetration. J Interpers Violence. 2006;21(10):1314–1332. doi: 10.1177/0886260506291657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rothman EF, Johnson RM, Young R, Weinberg J, Azrael D, Molnar BE. Neighborhood-level factors associated with physical dating violence perpetration: Results of a representative survey conducted in Boston, MA. J Urban Health. 2011;88(2):201–213. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9543-z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11524-011-9543-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing “neighborhood effects”: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual review of sociology. 2002:443–478. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141114.

- 52.Shorey RC, Stuart GL, McNulty JK, Moore TM. Acute alcohol use temporally increases the odds of male perpetrated dating violence: A 90-day diary analysis. Addict Behav. 2014;39(1):365–368. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reingle JM, Jennings WG, Connell NM, Businelle MS, Chartier K. On the pervasiveness of event-specific alcohol use, general substance use, and mental health problems as risk factors for intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2014;29(16):2951–2970. doi: 10.1177/0886260514527172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260514527172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reingle JM, Staras SAS, Jennings WG, Branchini J, Maldonado-Molina MM. The relationship between marijuana use and intimate partner violence in a nationally representative, longitudinal sample. J Interpers Violence. 2012;27(8):1562–1578. doi: 10.1177/0886260511425787. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0886260511425787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith PH, Homish GG, Collins RL, Giovino GA, White HR, Leonard KE. Couples’ marijuana use is inversely related to their intimate partner violence over the first 9 years of marriage. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28(3):734–742. doi: 10.1037/a0037302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0037302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moore T, Stuart G. A review of the literature on marijuana and interpersonal violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2005;10(2):171–192. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2004.10.002. [Google Scholar]

- 57.ACE Prevention Strategies. Centers for Disease Prevention and Control website. [Accessed March 5, 2015]; www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/ace/prevention_strategies.html. Updated Jan 14, 2014.