Abstract

Instrumental behavior often consists of sequences or chains of responses that minimally include procurement behaviors that enable subsequent consumption behaviors. In such chains, behavioral units are linked by access to one another and eventually to a primary reinforcer, such as food or a drug. The present experiments examined the effects of extinguishing procurement responding on consumption responding after training of a discriminated heterogeneous instrumental chain. Rats learned to make a procurement response (e.g., pressing a lever) in the presence of a distinctive discriminative stimulus; making that response led to the presentation of a second discriminative stimulus that set the occasion for a consumption response (e.g., pulling a chain), which then produced a food-pellet reinforcer. Experiment 1 showed that extinction of either the full procurement-consumption chain or procurement alone weakened the consumption response tested in isolation. Experiment 2 replicated the procurement extinction effect and further demonstrated that the opportunity to make the procurement response, as opposed to simple exposure to the procurement stimulus alone, was required. In Experiment 3, rats learned 2 distinct discriminated heterogeneous chains; extinction of 1 procurement response specifically weakened the consumption response that had been associated with it. The results suggest that learning to inhibit the procurement response may produce extinction of consumption responding through mediated extinction. The experiments suggest the importance of an associative analysis of instrumental behavior chains.

Keywords: heterogeneous behavior chains, instrumental learning, extinction, mediated extinction

Operant behavior usually consists of chains of linked behaviors that are each necessary to produce the primary reinforcer. Such chains minimally involve at least two behaviors: a response that directly yields the reinforcer (and can be called a “consumption” response) and a response that provides access to the consumption response (and can be called a “procurement” response; Collier, 1981). Other terms that have been used to refer to chained behaviors are given in Table 1. Behavior chains often include separate discriminative stimuli (SD) for each response; a procurement stimulus first sets the occasion for a procurement response, and a consumption stimulus then sets the occasion for a consumption response while also reinforcing the preceding procurement response (as a conditioned reinforcer, e.g., Gollub, 1977). In the laboratory, chained schedules (e.g., Catania, 1998) are typically arranged either for responses on a single manipulandum signaled by distinct SDs, or for different responses addressed to different manipulanda. The former, which may be referred to as homogeneous chains, have been used to study conditioned reinforcement (Williams, 1994). The latter, which may be referred to as heterogeneous chains, may or may not include explicit SDs setting the occasion for each response. When they do not include separate SDs, it is nonetheless common to assume that stimuli related to the response (e.g., proprioceptive feedback) might play a role analogous to that of more explicit discriminative stimuli (e.g., Catania, 1998).

Table 1.

Common Terms Used to Describe the Linked Behaviors in Heterogeneous Instrumental Chains

| Terms | Representative study |

|---|---|

| Procurement-Consumption | Collier, 1981 |

| Distal-Proximal | Balleine et al., 1995 |

| Seeking-Taking | Olmstead et al., 2001; Zapata et al., 2010 |

| R1–R2 | Ostlund, Winterbauer, & Balleine 2009 |

Note. R = Response.

The present experiments focused on discriminated heterogeneous behavior chains, which involved separate and explicit SDs for each behavior, because these may be most analogous to the chains individuals engage in when they procure and consume junk food or drugs of abuse (Ostlund & Balleine, 2008). To illustrate a discriminated heterogeneous chain, consider a simple sequence of behaviors that might be involved in human cigarette smoking. Here, a procurement response (e.g., buying cigarettes) occurs in the presence of a procurement stimulus (e.g., a cigarette machine or minimart) and then produces a consumption stimulus (e.g., a pack of cigarettes) that reinforces procurement and then sets the occasion for consumption (e.g., smoking). Because smoking is part of a behavior chain, successful quitting might benefit from suppressing each part of the chain. That is, a smoker might benefit from stopping both smoking and buying cigarettes. Extinction is a fundamental procedure and process in which organisms learn to quit performing operant behavior. An understanding of the extinction of heterogeneous chains may thus provide insight into methods for treating sequences of maladaptive behavior.

Recent work on heterogeneous chains has characterized the motivational processes affecting procurement and consumption. Balleine, Garner, Gonzalez, and Dickinson (1995; see also Balleine, Paredes-Olay, & Dickinson, 2005) investigated the effects of motivational shifts on the performance of heterogeneous chains. In a nondiscriminated procedure, consumption responses were found to be controlled by Pavlovian incentive process and immediately sensitive to changes in deprivation state. In contrast, procurement responses were only sensitive to changes in motivation after an experience with the outcome in the presence of the changed deprivation state (i.e., after incentive learning; Balleine, 1992). Corbit and Balleine (2003) provided a particularly clear example of the different motivational processes controlling procurement and consumption. Rats first received pretraining of Pavlovian pairings of two auditory stimuli with either grain or sucrose reinforcers. They then learned to perform a partially discriminated heterogeneous chain consisting of two lever press responses. Responses on a procurement lever caused insertion of a consumption lever; responses on the consumption lever were then reinforced with either grain or sucrose. In a test of Pavlovian-to-instrumental transfer (PIT), lever pressing on each response was compared in the presence and absence of each Pavlovian stimulus. Presentation of stimuli selectively increased a consumption response that had been associated with the same outcome (outcome-selective PIT). However, the same Pavlovian stimuli had no impact on procurement responding. In a second experiment, Corbit and Balleine (2003) showed that incentive learning enabled by eating food while nondeprived weakened procurement responding, but had no effect on consumption responding. These studies demonstrate that procurement and consumption responses may be influenced by doubly dissociable processes (see also Johnson, Bannerman, Rawlins, Sprengel, & Good, 2007; Wassum et al., 2012).

A small amount of research has been directed at understanding the extinction of behavior chains. Drug self-administration studies in rats have shown that extinction of the consumption response (drug taking) can decrease procurement responding (drug seeking). For example, Olmstead, Lafond, Everitt, and Dickinson (2001) trained rats to perform a discriminated chain in which insertion of a procurement lever set the occasion for procurement responses, which caused the procurement lever to retract and a consumption lever to be inserted. Consumption responses then led to an infusion of cocaine. In the next phase, the rats received extinction of the consumption response, in which repeated opportunities to press the consumption lever no longer led to the delivery of cocaine. A control group continued to receive response-contingent drug infusions. In a subsequent test of the procurement response, rats that had received extinction of consumption demonstrated weaker procurement behavior. The authors argued that the results suggest that procurement responding can be goal-directed in that it depends on the current status of its associated goal (see also Zapata, Minney, & Shippenberg, 2010).

It is worth noting that, in the world outside the laboratory, consumption behaviors are rarely extinguished this directly. For example, the drug injector rarely injects saline instead of the drug, and a smoker rarely smokes denicotinized cigarettes. Can an associative analysis of behavior chains nevertheless suggest other ways to depress consumption responding? One possibility is that, if procurement and consumption become associated, as the effects of consumption extinction on procurement suggest, then extinction of procurement might conversely weaken consumption. Thus, inhibition of cigarette purchasing (procurement) might have an impact on smoking (consumption) when a pack of cigarettes is later available. Such a result would be consistent with research in Pavlovian conditioning suggesting that extinction can occur to a stimulus that has been associated with another stimulus that is put directly through extinction (Holland, 1990; Holland & Ross, 1981; Holland & Wheeler, 2009). The present experiments were designed to ask whether such mediated extinction can also occur with instrumental chains. We developed a discriminated chain procedure modeled roughly on conditions in which individuals procure and consume food, drugs, or cigarettes as explained previously. Procurement and consumption responses thus occurred in the presence of distinct SDs. In addition to modeling what might be an important aspect of natural behavior chains, the present approach allowed us to begin to characterize the crucial associations between responses, SDs, and reinforcers that might develop and control performance in such a situation.

Rats were first trained to perform a discriminated heterogeneous chain. Experiment 1 then demonstrated that extinction of either the full chain or procurement responding in isolation can indeed weaken consumption responding. Experiment 2 further suggested that the effect of procurement extinction depends on the rats making the actual procurement response in extinction. Experiment 3 then ruled out other nonspecific processes as potential explanations for the effect, and further supported an account of the effect based on mediated extinction (e.g., Holland, 1990).

Experiment 1

The design of Experiment 1 is shown in Table 2. It sought to characterize simple extinction of a discriminated behavior chain and its effects on performance of the consumption response. Three groups of rats learned to perform a chain that involved both lever-press and chain-pull responses (order counterbalanced). On each trial, an SD (panel light) signaled the opportunity to perform a procurement response. Procurement responding then resulted in the presentation of a second SD that in turn signaled the opportunity to perform a consumption response for a food pellet reinforcer. Each presentation of the procurement SD was separated by a variable intertrial interval (ITI). Following the acquisition of chain performance, groups received one of three treatments. Group Chain Extinction received extinction of the entire chain, in which the rats were repeatedly allowed to perform the entire procurement-consumption sequence without the delivery of a food pellet. Group Procurement Extinction received extinction of procurement only, in which responses on the procurement manipulandum in the presence of the procurement SD did not produce the consumption SD (or the final delivery of a food pellet). Group Handle received equivalent handling without exposure to the SDs, responses, or operant chamber. Rats were then tested for consumption responding in the presence of the consumption SD alone. The question was whether extinction of procurement responding alone might cause a decrement in consumption responding, and whether such extinction was more or less effective at weakening consumption than extinction of the full chain.

Table 2.

Experimental Designs

| Group | Acquisition | Extinction | Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | |||

| Chain extinction | SP:P→SC:C+ (P, C) | SP:P→SC:C− (P, C) | SC:C− (P, C) |

| Procurement extinction | SP:P→SC:C+ (P, C) | SP:P− (P) | SC:C− (P, C) |

| Handle | SP:P→SC:C+ (P, C) | — | SC:C− (P, C) |

| Experiment 2 | |||

| SP-P (C) | SP:P→SC:C+ (P, C) | SP:P− (P, C) | SC:C− (P, C) |

| SP-P | SP:P→SC:C+ (P, C) | SP:P− (P) | SC:C− (P, C) |

| SP only | SP:P→SC:C+ (P, C) | SP: − | SC:C− (P, C) |

| Handle | SP:P→SC:C+ (P, C) | — | SC:C− (P, C) |

| Experiment 3 | |||

| Extinguished | SP1:P1→SC1:C1+ (P1, C1, P2, C2) | SP1:P1− (P1) | SC1:C1− (C1, C2) |

| SP2:P2→SC2:C2+ | SC2:C2− (C1, C2) | ||

| Handle | SP1:P1→SC1:C1+ (P1, C1, P2, C2) | — | SC1:C1− (C1, C2) |

| SP2:P2→SC2:C2+ | SC2:C2− (C1, C2) | ||

Note. P and C, and SP and SC refer to procurement and consumption responses, and discriminative stimuli, respectively. + designates reinforcement, − designates nonreinforcement (extinction), — designates handling without exposure to the experimental apparatus. Parentheses indicate which response manipulanda were present.

Method

Subjects

Twenty-four female rats (75–90 days old) were housed in suspended wire mesh cages and maintained at 80% of their free-feeding weights. Rats had unlimited access to water in their homecages and were given supplementary feeding approximately 2 hr after each session.

Apparatus

The apparatus consisted of two unique sets of four conditioning chambers (model ENV-007-VP; Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) located in separate rooms of the laboratory. Each chamber was housed in its own sound-attenuating chamber. All boxes measured 31.75 × 24.13 × 29.21 cm (length × width × height). The sidewalls consisted of clear acrylic panels, and the front and rear walls were made of brushed aluminum. A recessed food cup was centered on the front wall approximately 2.5 cm above the floor. A retractable lever (model ENV-112CM, Med Associates) was positioned to the left of the food cup. The lever was 4.8 cm wide and 6.3 cm above the grid floor. It protruded 2.0 cm from the front wall when extended. A chain-pull response manipulandum (model ENV-111C, Med Associates) was positioned to the right of the food cup. The chain was 23.5 cm long and 5.7 cm above the grid floor. It was spaced 2.0 cm from the front wall. Two 28-V (2.8 W) panel lights (diameter = 2.5 cm) were mounted on the wall near each manipulandum, 10.8 cm above the floor and 6.4 cm from the center of food cup. One light was immediately above the lever and the other was behind the chain. The chambers could be illuminated by 7.5-W incandescent bulbs mounted to the ceiling of the sound-attenuation chamber. Ventilation fans provided background noise of 65 dBA.

The two sets of chambers had unique features that allowed them to serve as different contexts in other experiments, although they were not used for that purpose here. In one set of boxes, the floor consisted of 0.5 cm diameter stainless steel floor grids spaced 1.6 cm apart (center-to-center) and mounted parallel to the front wall. The ceiling and side wall had black horizontal stripes, 3.8 cm wide and 3.8 cm apart. In the other set of chambers, the floor consisted of alternating stainless steel grids with different diameters (0.5 and 1.3 cm, spaced 1.6 cm apart). The ceiling and side wall were covered with dark dots (2 cm in diameter). Reinforcement consisted of the delivery of a 45 mg food pellet into the food cup (MLab Rodent Tablets; TestDiet, Richmond, IN). The apparatus was controlled by computer equipment in an adjacent room

Procedure

Food restriction began one week prior to the beginning of training. During training, one session was conducted each day, 7 days a week. Animals were handled each day and maintained at their target weight with supplemental feeding when necessary.

Acquisition

Rats first received two 30-min sessions of magazine training with response manipulanda removed. In each session, there were 60 noncontingent pellet deliveries scheduled according to a random time (RT) 30 s schedule. Over the next two sessions, the consumption response was trained. At this time, only the consumption manipulandum was present and the consumption stimulus was presented on 30 trials with a 45 s variable ITI. Manipulanda (lever or chain) were counterbalanced across subjects; the consumption SD was always the panel light near the consumption manipulandum. A consumption response turned the SD off and immediately produced a food pellet according to a continuous reinforcement (CRF) schedule. A trial was terminated if a response was not made within 20 s of stimulus onset. In the following session, the procurement response manipulandum was added to the chamber. At the start of each of 30 trials, the new procurement SD (panel light near the procurement manipulandum) was now turned on. A single procurement response in the presence of the procurement SD turned off the stimulus, and immediately turned on the consumption SD, in the presence of which a single consumption response then produced a food pellet. Training of both responses on CRF proceeded this way for four sessions. Next, there were two sessions in which the response requirement was increased to random ratio (RR) 2 in both links of the chain. Finally, over the last 6 sessions of the phase, the response requirement was RR 4 in both links. Sessions lasted approximately 35 min. Two rats failed to acquire the chain with RR 4 and were dropped from the experiment (N = 22).

Extinction

Once acquisition was finished, rats were separated into three groups matched on percentage of the trials that were successfully completed (i.e., ended in reinforcement) in the last session of acquisition. Two groups then received extinction sessions in which the rats were either allowed to complete the entire RR 4 procurement-consumption chain without a pellet (Group Chain Extinction; n = 7), or were allowed to complete the procurement link with RR 4 without a consumption stimulus following it (Group Procurement Extinction; n = 8). For the latter group, procurement responding continued to terminate the procurement SD. The consumption manipulandum had been removed. The remaining rats (Group Handle, n = 7) were not run in sessions but were handled in an equivalent manner to the other groups. There were three extinction sessions that each involved 30 trials. If responding failed to meet the RR4 requirement in either SD, trials ended after 20 s.

Consumption test

After three sessions of extinction, all rats received a test session in which both response manipulanda were present. There were 30 consumption trials, that is, 30 occasions on which the consumption SD was presented without being preceded the procurement SD. Trials were separated by a variable 45-s ITI. Responses on the consumption manipulandum during the consumption SD turned off the stimulus according to RR 4, but did not produce a food pellet. Consumption trials otherwise ended with the SD going off after 20 s had elapsed.

Data analysis

To describe procurement and consumption responding occasioned by the corresponding SD, we calculated elevation scores by subtracting the response rate on procurement and consumption manipulanda during the 30 s immediately before the procurement stimulus was presented (the preprocurement period) from the response rate during the procurement and consumption stimuli, respectively. The elevation scores and preprocurement response rates were evaluated with analyses of variance (ANOVAs) using a rejection criterion of p < .05. Effect sizes are reported where appropriate. Confidence intervals (CIs) for effect sizes were calculated according to methods suggested by Steiger (2004).

Results

Acquisition

Each group acquired reliable performance of the chain during the acquisition phase. Figure 1a shows procurement and consumption elevation scores as a function of RR 4 session in acquisition in all groups. Elevation scores were analyzed in a Group (3) × Session (6) repeated-measures ANOVA. The analysis confirmed a significant increase in procurement responding across sessions of acquisition, F(5, 95) = 7.42, MSE = 30.94, p < .01, , 95% CI [.11, .38], and found no differences between groups and no interaction, Fs < 1. Consumption elevation scores were similarly compared in a Group (3) × Session (6) ANOVA. Consumption responding increased across sessions of acquisition, F(5, 95) = 17.37, MSE = 37.40, p < .01, , 95% CI [.31, .57]; there were no differences between groups and no interaction, largest F = 1.39. Mean procurement response rates in the preprocurement SD period were 3.5, 6.4, and 7.9 in the first session of RR 4 training, and 5.2, 7.6, and 12.9 in the final session for Groups Chain, Procurement, and Handle, respectively. A Group × Session ANOVA comparing procurement response rates in the preprocurement SD period found no significant effects of session or group, and no interaction, largest F = 2.05. Mean consumption response rates in the preprocurement SD period were 6.5, 4.7, and 4.8 in the first session of RR 4 training, and 3.4, 3.7, and 3.6 in the final session for Groups Chain, Procurement, and Handle, respectively. A Group × Session ANOVA comparing consumption response rates in the preprocurement SD period found a significant decrease in responding across sessions, F(1, 19) = 24.35, MSE = 2.40, p < .01, , 95% CI [.21, .72], and no group difference or interaction, largest F = 1.78.

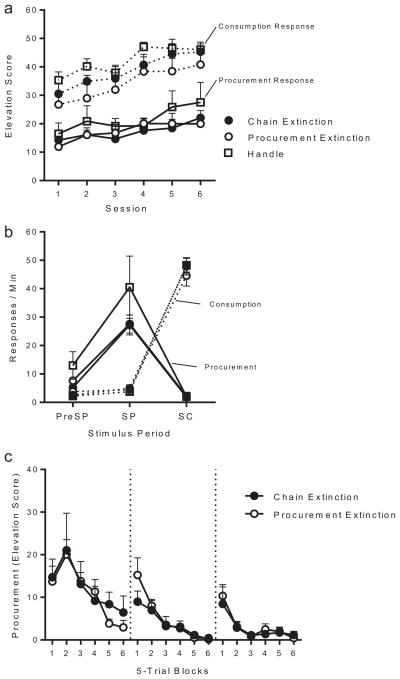

Figure 1.

Acquisition and extinction of responding in Experiment 1. (a) Acquisition of procurement and consumption responding. (b) Procurement and consumption response rates during preprocurement, procurement, and consumption discriminative stimuli periods (preprocurement [Pre-SP], procurement [SP], and consumption [SC], respectively) during the final session of acquisition. (c) Elevation scores of Procurement response rates in 4-trial blocks across sessions of extinction. Error bars are the SEM, and only appropriate for between-groups comparisons.

By the final session of acquisition, procurement and consumption responding were under good stimulus control. Figure 1b shows low levels of procurement and consumption responding during the preprocurement period, elevated procurement responding (but not consumption responding) in the procurement stimulus, and elevated consumption responding (but not procurement responding) in the consumption stimulus. Separate Group (3) × Response (procurement vs. consumption) ANOVAs applied to response rates during each period confirmed these observations. In preprocurement, there was more procurement than consumption responding, F(1, 19) = 10.78, MSE = 33.37, p = .004, η2 = .36, 95% CI [.05, .59]. Groups did not differ in the amount of responding, F(2, 19) = 1.35, MSE = 35.94. p = .28, and there was no Group × Response interaction, F(2, 19) = 2.05, p = .15. In the procurement stimulus, there was more procurement than consumption responding, F(1, 19) = 48.48, MSE = 169.47, p < .001, η2 = .72, 95% CI [.43, .82]. Groups did not differ in the amount of responding, F(2, 19) = 1.05, MSE = 168.42. p = .37, and there was no Group × Response interaction, F(2, 19) = 1.37, p = .28. In the consumption stimulus, there was more consumption than procurement responding, F(1, 19) = 737.24, MSE = 29.96, p < .001, η2 = .97, 95% CI [.94, .98]. Groups did not differ in the amount of responding, and there was no Group × Response interaction, Fs < 1.

Extinction

Figure 1c shows procurement responding over 5-trial blocks in each session of extinction. Procurement responding decreased rapidly, and at a similar rate, in the Chain Extinction and Procurement Extinction groups. A Group (Chain vs. Procurement) by Block (6) × Session (3) ANOVA supported these observations. There were significant effects of session, F(2, 26) = 21.93, MSE = 85.08, p < .001, , 95% CI [.33, .74], and block, F(5, 65) = 14.88, MSE = 48.13, p < .001, , 95% CI [.33, .62], as well as a Session × Block interaction, F(10, 130) = 4.18, MSE = 30.10, p < .001, , 95% CI [.07, .31]. There was no effect of group, and no interactions of group with session or block, Fs < 1. Mean procurement response rate in the preprocurement SD period was 1.4 and 1.8 for Groups Chain Extinction and Procurement Extinction in the first session of extinction and 0.7 and 0.9 during the final session, respectively. A Group × Block × Session ANOVA on these data revealed a main effect of block, F(5, 65) = 5.34, MSE = 3.63, p < .001, , 95% CI [.08, .41], and a marginal effect of session, F(2, 26) = 3.33, MSE = 4.73, p = .05, , 95% CI [.00, .41], but no group effect or interaction, largest F = 1.30.

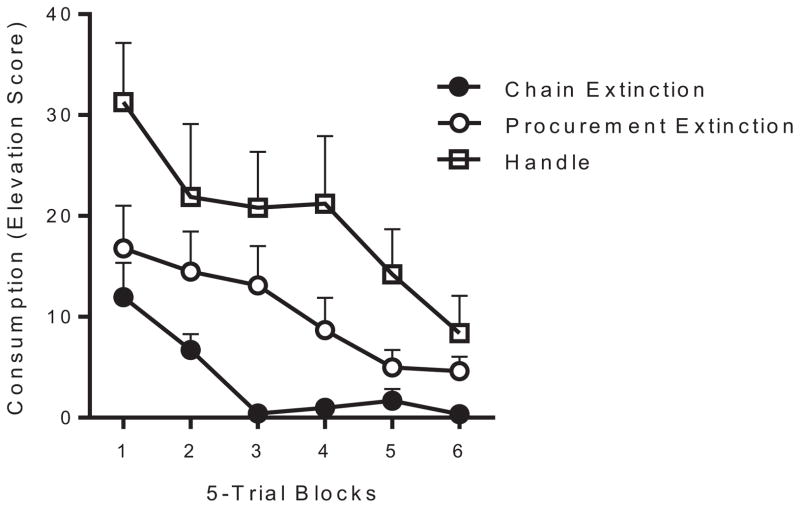

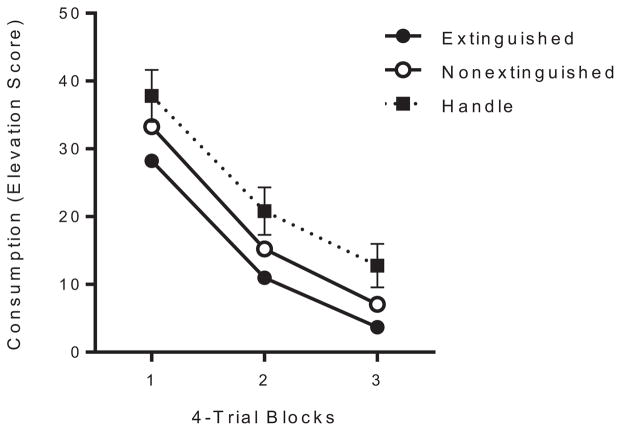

Consumption test

Figure 2 shows consumption responding (elevation scores) over the 30 tests of the consumption stimulus alone. Responding was highest in the Handle group, which had received no extinction, and lowest in the Chain Extinction group. The Procurement Extinction group showed an intermediate level of responding. A Group (3) × Block (6) ANOVA confirmed these observations. There were significant effects of group, F(2, 19) = 6.53, MSE = 413.03, p < .01, , 95% CI [.05, .60], and block F(5, 95) = 13.65, MSE = 48.79, p < .001, , 95% CI [.24, .51], which did not interact, F(10, 95) = 1.26, p = .26. Planned comparisons found consumption responding in Group Procurement Extinction to be lower than that in Group Handle, p = .04, suggesting that procurement extinction had weakened consumption responding. In addition, while Group Chain Extinction responded significantly less than Group Handle, p < .01, consumption responding in the Chain and Procurement groups did not differ significantly, p = .13. The lack of a statistical difference between Groups Chain and Procurement, which was not the main focus of the experiment, could have been because of insufficient statistical power. The use of elevation scores was not complicated by group differences in responding in the preconsumption SD periods. Average consumption response rates in the preconsumption SD period were 0.1, 0.5, and 0.3 in the first block and 0.00, 0.01, and 0.02 in the final block for Groups Chain Extinction, Procurement Extinction, and Handle, respectively. A Group × Block ANOVA found a significant decrease in consumption response rate during preconsumption SD periods, F(5, 95) = 11.03, MSE = 0.02, p < .001, , 95% CI [.19, .47], but no group difference or interaction, largest, F = 1.75.

Figure 2.

Test of consumption responding in Experiment 1. Consumption response rate elevation scores across blocks of 5 consumption stimulus discriminative stimuli presentations. Error bars are the SEM.

Discussion

The rats learned the discriminated heterogeneous chain and showed excellent stimulus control of each behavior by the end of training. More important, extinction of either the entire procurement-consumption chain or procurement alone was found to weaken subsequent consumption responding when it was tested separately. It is important that the Procurement Extinction group responded significantly less than the Handle group, which did not experience extinction. This result adds to previous studies that have shown that extinction of one component of a chain can weaken responding in the other component (Olmstead et al., 2001; Zapata et al., 2010). However, the present results are the first to show that procurement extinction weakens consumption, as opposed to the reverse. Either effect is consistent with the possibility that the animal associates the procurement and consumption links (whether stimuli or behavior) during training.

One surprising finding was that the Procurement and Chain Extinction groups did not differ in their procurement responding during extinction. For the Chain Extinction group, the procurement response led to the consumption SD, a putative conditioned reinforcer, even though it did not lead to food. The lack of difference between the groups suggests that any conditioned reinforcing value of the consumption SD was not particularly effective in prolonging extinction in the Chain Extinction group. To our knowledge, this is the first examination of conditioned reinforcement in the context of extinction of a heterogeneous instrumental chain (Fantino, 1965). The fact that there was so little evidence of it suggests that presentation of the consumption SD as a consequence of procurement responding is not a crucial contingency within the present method. It is also worth noting that Group Chain Extinction, but not Group Procurement Extinction, had the consumption manipulandum present during extinction. If anything, this also should have promoted more responding in Group Chain Extinction because of enhanced stimulus generalization from the acquisition phase. The results suggest that neither conditioned reinforcement provided by the consumption SD nor the presence of the consumption manipulandum in the chamber had much impact on procurement responding during the procurement extinction phase.

The main finding of the experiment, however, is that exposure to the procurement SD and the procurement response during extinction (Group Procurement Extinction) was sufficient to weaken consumption responding during the consumption test.

Experiment 2

Recent studies have identified an important role for the response in instrumental extinction learning (Bouton, Todd, Vurbic, & Winterbauer, 2011; Todd, 2013; Todd, Vurbic, & Bouton, 2014). Making the response in extinction may be necessary to extinguish it (cf. Rescorla, 1997). For example, in a study of ABA renewal, where the response returns in the original conditioning context (A) after extinction in a second context (B), Bouton et al. (2011, Experiment 4) found that exposure to Context A alone, without the opportunity to make the lever-pressing response, was insufficient to reduce the renewal effect. Other evidence suggests that making a specific response in extinction reduces renewal of the same response in that context, but not a different response, when the responses are controlled by different SDs (Todd et al., 2014). These results and others (Todd, 2013) suggest that instrumental extinction results in a form of context-dependent inhibition of a specific response.

Experiment 2 was therefore conducted to replicate and explore the role of the response in the effect of procurement response extinction on consumption behavior. Its design is summarized in Table 2. Rats were first trained to perform the discriminated heterogeneous chain studied in Experiment 1. Next, three groups received a series of extinction exposures to the procurement SD with either (1) both the procurement and consumption manipulanda present [Group SP-P (C)], (2) the procurement manipulandum but not the consumption manipulandum present (Group SP-P) (as in Experiment 1), or (3) neither manipulandum present (Group SP only). The presence/absence of the different manipulanda during extinction arranged things so that Group SP-P (C) could make both responses, Group SP-P could only make procurement responses, and Group SP only could not make either. The consumption SD was never presented. A fourth group received the same treatment as Group Handle in Experiment 1. All groups were then tested for consumption responding during trials in which the consumption stimulus was presented, in extinction, with the opportunity to make either the consumption or the procurement response. The extinction groups allowed us to assess whether learning to inhibit the procurement response is required for procurement extinction to weaken the consumption response. If mere exposure to the procurement SD were sufficient to weaken the consumption response, then Group SP only would show weakened consumption responding, as we expected in Groups SP-P and SP-P (C). The inclusion of both Group SP-P and Group SP-P (C) allowed us to assess any influence of the presence versus absence of the consumption manipulandum while procurement responding was extinguished.

Method

Subjects and apparatus

Thirty-two female Wistar rats from the same supplier were used. Their age, housing, and maintenance conditions were identical to those described in Experiment 1. The apparatus was also the same as that used in Experiment 1.

Procedure

Acquisition

Sessions were conducted daily and lasted approximately 30 min. All rats experienced each training phase, and were given brief remedial training in a separate session if they failed to respond during the main session. Magazine and consumption response training followed the procedure used in Experiment 1, with the exception that the stimulus was terminated after 60 s if there was no response. On the next session, the procurement manipulandum was introduced and training of the entire chain commenced in a similar manner to that in Experiment 1. Following two sessions of CRF chain training, there were two sessions in which the schedule in both links was RR 2. For the remaining sessions, the schedule was always RR 4 in both links. Time allowed in the procurement and consumption stimuli to meet the RR 4 requirement decreased in steps from 60 s, 45 s, 30 s, to the terminal value of 20 s over the first four sessions of RR 4 training. The maximal stimulus duration of 20 s remained in effect for a final 4 sessions of acquisition.

Extinction

Rats were then randomly assigned to one of four groups (ns = 8). Over the next four sessions, three of the groups received extinction sessions in which there were 30 presentations of the procurement stimulus without reinforcement. In Groups SP-P (C) and SP-P, procurement responding terminated the stimulus on RR 4, but did not produce the consumption stimulus or an opportunity to earn a food pellet. For Group SP-P (C), both the procurement and consumption manipulanda were available. For Group SP-P, only the procurement manipulandum was present (the consumption manipulandum was removed). For Group SP only, neither manipulandum was present; these rats merely received 30 20-s presentations of the procurement stimulus in the absence of reinforcement. Treatment of Group Handle was the same as in Experiment 1.

Consumption test

On the day following the last extinction session, all rats were given a test of consumption responding with both manipulanda following the procedure used in Experiment 1.

Results

Acquisition

Training of the instrumental chain was successful. All rats acquired performance of the chain on RR 4. Figure 3a presents procurement and consumption responding expressed as elevation scores during the eight sessions of RR 4 training. During acquisition, procurement elevation scores were compared in a Group (4) × Session (8) ANOVA. The analysis found a significant increase in responding across sessions, F(7, 196) = 15.67, MSE = 17.54, p < .01, , 95% CI [.23, .43], but no group effect or Group × Session interaction, Fs < 1. Consumption responding during acquisition also increased across sessions, F(7, 196) = 14.96, MSE = 83.28, p < .001, , 95% CI [.22, .42], with no effect of group or interaction, Fs < 1. Average procurement response rates in the preprocurement SD period were 4.4, 5.0, 8.1, and 6.5 in the first session of RR 4 chain training and 8.4, 7.9, 11.7, and 9.3 in the final session for Groups SP-P (C), SP-P, SP only, and Handle, respectively. A Group × Session ANOVA found a significant increase in procurement responding in the preprocurement SD period over sessions, F(7, 196) = 8.34, MSE = 5.48, p < .001, , 95% CI [.11, .30], but no effect of group or interaction, Fs < 1. Average consumption response rates in the preprocurement SD period were 4.3, 8.3, 4.5, and 5.4 in the first session of RR 4 chain training and 2.6, 7.2, 3.9, and 3.6 in the final session for Groups SP-P (C), SP-P, SP only, and Handle, respectively. A Group × Session ANOVA found a significant decrease in consumption responding in the preprocurement SD period over sessions, F(7, 196) = 3.56, MSE = 3.74, p = .001, , 95% CI [.02, .17], and no group effect or interaction, largest F(3, 28) = 1.98.

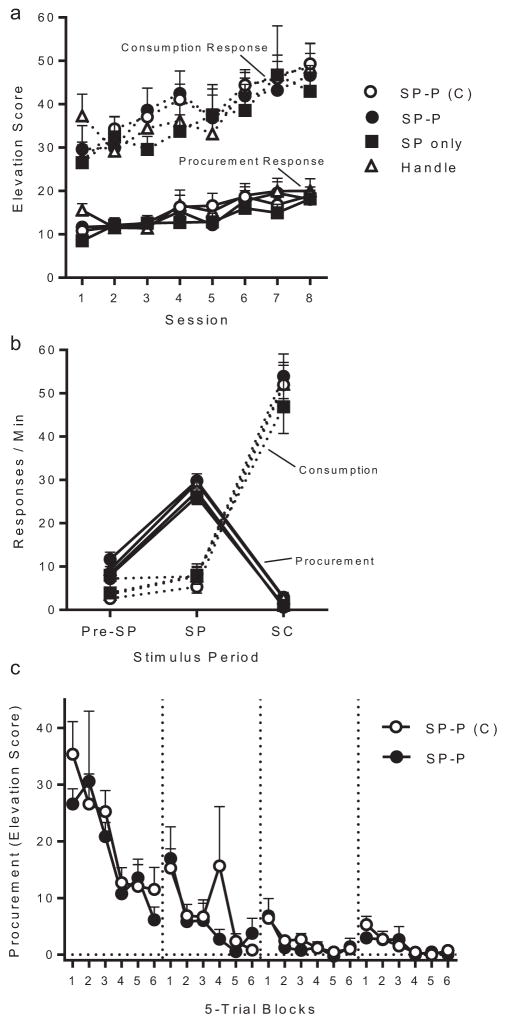

Figure 3.

Acquisition and extinction of responding in Experiment 2. (a) Acquisition of procurement and consumption responding in each group. (b) Response rates in each group during preprocurement (Pre-SP), procurement (SP), and consumption (SC) discriminative stimuli periods in the final session of acquisition. (c) Elevation scores of Procurement response rates in 4-trial blocks across sessions of extinction. Error bars are the SEM, and only appropriate for between-groups comparisons.

Figure 3b shows procurement and consumption responding during preprocurement, procurement, and consumption stimulus periods in the final session of acquisition. As in Experiment 1, there was excellent stimulus control by the end of training. Response rates were low during the preprocurement period, and procurement responding appropriately increased during the procurement stimulus and were replaced by consumption responding during consumption stimulus presentations. Separate Group (4) by Manipulandum (procurement vs. consumption) ANOVAs confirmed these observations. In the preprocurement period, the rats made more procurement than consumption responses, F(1, 28) = 17.44, MSE = 22.84, p < .001, η2 = .38, 95% CI [.11, .58]. There was also a difference in the overall amount of preprocurement period responding between groups, F(3, 28) = 5.74, MSE = 8.86, p = .003, η2 = .38, 95% CI [.06, .54], but no interaction, F < 1. Planned comparisons identified higher preprocurement responding in the SP-P group, and no differences in the remaining groups. In the procurement stimulus period, procurement responses were higher than consumption responses, F(1, 28) = 189.53, MSE = 36.99, p < .001, η2 = .87, 95% CI [.76, .91], and there was no group difference or interaction, Fs < 1. In the consumption stimulus, consumption response rates were in turn higher than procurement response rates, F(1, 28) = 382.93, MSE = 36.99, p < .001, η2 = .93, 95% CI [.87, .95], with no group effect or interaction, Fs < 1.

Extinction

During extinction (Figure 3c), procurement responding in Groups SP-P (C) and SP-P decreased systematically. This observation was confirmed by a Group [SP-P (C) versus SP-P] × Block (6) by Session (4) ANOVA. There were significant effects of session, F(3, 42) = 57.35, MSE = 113.42, p < .001, , 95% CI [.67, .85], and block, F(5, 70) = 14.12, MSE = 83.17, p < .001, , 95% CI [.30, .60], and a Session × Block interaction, F(15, 210) = 3.49, MSE = 78.94, p < .001, , 95% CI [.06, .24]. There were no significant effects or interactions involving group, largest F = 1.18. Procurement responding in the preprocurement SD period was 3.2 and 3.1 for Groups SP-P (C) and SP-P in the first session of extinction and 0.6 and 0.5 during the final session respectively. A Group [SP-P (C) versus SP-P] by Block (6) × Session (4) ANOVA found significant effects of session, F(3, 42) = 28.95, MSE = 1.29, p < .001, , 95% CI [.47, .76], block, F(5, 70) = 9.76, MSE = 1.00, p < .001, , 95% CI [.20, .52], and a Session × Block interaction, F(15, 210) = 4.21, MSE = .81, p < .001, , 95% CI [.09, .27]. It is important, again, that there were no significant effects or interactions involving group, Fs < 1. As an additional analysis, the average amount of time spent in the presence of the procurement SD in extinction was compared for SP-P (C), SP-P, and SP only groups. Recall that Group SP only was not able to respond, and therefore experienced the full 20 s SD in each presentation, whereas the other groups terminated the SD if they satisfied the RR 4 requirement. Groups SP-P (C) and SP-P experienced the procurement SD for a mean of 16.1 s and 16.8 s per stimulus, respectively. A one-way ANOVA found an overall group difference, F(2, 21) = 50.28, MSE = 0.69, p < .001, η2 = .83, 95% CI [.63, .88]. Follow-up comparisons (Tukey) found no difference between Groups SP-P (C) and SP-P, p > .05, and revealed that both of these groups had less time in the stimulus than Group SP only, ps < .01.

For Group SP-P (C), the consumption manipulandum was uniquely present during extinction, and it is interesting to note that consumption responding did in fact occur after the completion of the procurement RR requirement. We examined consumption responding in this group immediately after the procurement SD was successfully terminated. During Sessions 1 and 4, the mean consumption response rate in the time period just after the procurement SD that was equal in duration to the average time spent in the SD (10.6 s and 18.8 s, respectively) was 5.5 and 0.6, respectively. In the baseline period (preprocurement SD period) it was 1.5 and 0.4. A Period (Pre vs. Post) × Session (4) ANOVA revealed a significant elevation of consumption responding after completing the procurement requirement, F(1, 7) = 7.77, MSE = 1.39, p = .03, , 95% CI [.00, .75]. There was also a reliable decrease in consumption responding over sessions of extinction, F(3, 21) = 10.69, MSE = 2.87, p < .01, , 95% CI [.23, .72], but no interaction, F = 1.93, MSE = 1.22.

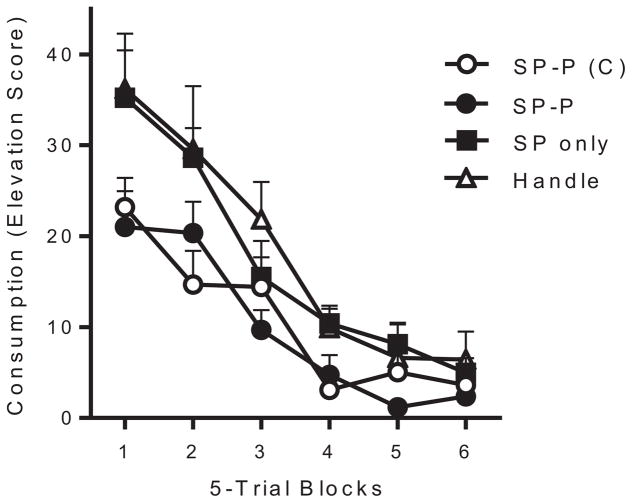

Consumption test

Figure 4 shows the results of the test of consumption responding. Consumption was weaker in the groups that had received extinction of the procurement response [Groups SP-P (C) and SP-P] than in the other groups. A Group (4) × Block (6) ANOVA found significant effects of group, F(3, 28) = 3.55, MSE = 258.05, p = .03, , 95% CI [.00, .45], and block, F(5, 140) = 51.35, MSE = 66.03, p < .001, , 95% CI [.54, .70], but no interaction, F(15, 140) = 1.18, p = .29. Planned comparisons found that Groups SP only and Handle responded more than Groups SP-P (C) and SP-P, ps = .05, and .03, .02, and .01, respectively, but did not differ from each other, p = .7. Groups SP-P (C) and SP-P did not differ from each other, p = .81. The use of elevation scores was not complicated by differences in ITI responding. Mean consumption response rates in the preconsumption SD period were 1.6, 3.9, 3.1, and 2.3 in the first block of the Consumption test and 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, and 0.1 in the last block for Groups SP-P (C), SP-P, SP only, and Handle, respectively. A Group × Block ANOVA found a significant decrease in consumption response rates during the preconsumption SD period, F(5, 140) = 22.84, MSE = 1.27, p < .001, , 95% CI [.31, .53], and no effect of group, or interaction, largest F = 1.19.

Figure 4.

Consumption test in Experiment 2. Consumption response rate elevation scores across blocks of 5 consumption discriminative stimuli presentations. Error bars are the SEM.

Discussion

As in Experiment 1, after training with the discriminated heterogeneous chain, groups that received procurement extinction showed weakened consumption responding. However, the results also establish that the performance of the procurement response in extinction [Groups SP-P (C) and SP-P] is required to observe this effect. Simple exposure to the procurement SD only (Group SP only) was not sufficient to suppress consumption responding. Interestingly, the impact of SD-only exposure was weaker than response exposure even though the SD-only animals received more time being exposed to the procurement SD. From a mediated extinction perspective, the fact that SD-only exposure had so little effect on consumption responding suggests that retrieval during extinction of several events that might be associated with the SD (e.g., the consumption SD, or, more remotely, the reinforcer itself) are not sufficient to weaken the consumption response. It is also worth noting that the rats in Group SP-P (C) often emitted the consumption response after completing the procurement response requirement during extinction—even though no consumption SD was presented. That result suggests that the consumption SD was not necessary to set the occasion for the consumption response. Performance of the procurement response (or perhaps termination of the procurement SD) was instead sufficient to promote consumption. Notice, however, that termination of the procurement SD—which was experienced by Group SP-only—was not sufficient to weaken consumption responding. The results thus begin to suggest that making the procurement response may play the major role in reducing consumption behavior because it is directly associated with (and evokes a representation of) the consumption response (or consumption response/SD combination). It is also worth noting that, although rats in Group SP-P (C) did emit the consumption response during the present extinction phase, the results of Group SP-P (as well as Group Procurement Extinction in Experiment 1) suggest that emitting the consumption response during extinction is not essential to weaken consumption responding during testing; in these cases, procurement response extinction weakened subsequent consumption responding even when the consumption manipulandum was not available.

It is possible that SD-only exposure failed to affect consumption responding because of reduced stimulus generalization between the conditions of procurement extinction and consumption testing: Unlike Groups SP-P (C) and SP-P, Group SP-only had no response manipulanda present during the extinction phase. It is worth noting, however, that the presence/absence of response manipulanda had little effect on generalization in Experiments 1 and 2. For example, in the present experiment, the absence of the consumption lever in Group SP-P during extinction did not prevent that group from showing the same effect on consumption responding as the group that had both manipulanda during extinction and testing [Group SP-P (C)]. And in Experiment 1, a group that had both manipulanda present during procurement extinction (Group Chain Extinction) showed no more procurement responding than a group that had only the procurement manipulandum available (Group Procurement Extinction). In and of themselves, the presence/absence of the response manipulanda do not appear to support much stimulus generalization in the present method.

Experiment 3

As we have noted throughout this article, extinction of procurement may have weakened consumption responding in Experiments 1 and 2 through a process related to mediated extinction. Holland (1981, 1985, 1990; Holland & Wheeler, 2009) has extensively documented such a process in Pavlovian conditioning situations. In an example that may be especially relevant to the current experiments, Holland and Ross (1981, Experiment 2b) studied mediated extinction after training a light-tone-food sequential compound. During conditioning, rats received a 5-s light followed immediately by a 5-s tone before receiving a food-pellet reinforcer. In one experiment, subsequent extinction of the light alone was found to weaken the ability of the tone to evoke conditioned responding (head-jerking) when it was tested alone. Holland and Ross argued that after light-tone-food conditioning, nonreinforced light-alone presentations activated a representation of the tone, which allowed the tone as well as light to undergo extinction. They also showed that only responding to the specific stimulus trained in serial compound with the extinguished element was weakened when they had first trained the rats with two separate serial compounds in a within-subject design.

In Experiments 1 and 2, making the procurement response during extinction may have analogously activated a representation of the consumption link (SD and/or response) through an association formed during training of the discriminated chain. This may have allowed the consumption response to undergo extinction in a manner analogous to the Holland and Ross (1981) result. However, neither Experiment 1 nor Experiment 2 presented evidence to favor this account over at least two other possibilities. For one thing, learning to inhibit the procurement response may have generalized to some extent to the consumption response (although the strong stimulus control of procurement and consumption at the end of training indicates that the animals clearly discriminated between the two responses). Alternatively, extinction of procurement responding could have generated frustration (e.g., Amsel, 1962) or some other process that could have interfered with both responses generally.

To separate such possibilities from mediated extinction, Experiment 3 asked whether extinction of procurement weakens only a consumption response that was specifically associated with it. Its design is summarized in Table 2. Animals first learned to perform two separate discriminated heterogeneous chains. Two new response manipulanda were added to the conditioning chambers so that two procurement responses (P1 and P2) were available along with two consumption responses (C1 and C2). Training consisted of intermixed presentations of two procurement SDs which signaled that either P1 or P2 could be performed to gain access to food by performing a specific consumption response (C1 or C2). Thus, one chain consisted of P1-C1 and the other consisted of P2-C2. Following acquisition, an experimental group received extinction of one procurement response (e.g., P1), and a control group received only equivalent handing. The groups were then tested on both consumption responses (C1 and C2). If extinction of procurement weakens consumption responding through frustration or generalization between responses, then extinction of P1 should weaken the two consumption responses to a similar extent. However, if extinction of procurement weakens consumption responding through mediated extinction, then extinction of P1 will primarily weaken the consumption response that was specifically associated with it (C1). Although the critical test of mediated extinction was within-subject (i.e., C1 vs. C2 in the experimental group), the handling control group was also included to assess whether other nonspecific factors might play an additional role.

Method

Subjects

Thirty-two female Wistar rats from the same supplier were used. Their age, housing, and maintenance conditions were identical to those described in Experiments 1 and 2.

Apparatus

The apparatus consisted of two unique sets of four conditioning chambers (model ENV-008-VP; Med Associates) housed in separate rooms of the laboratory. Each chamber was in its own sound attenuation chamber. All boxes measured 30.5 × 24.1 × 23.5 cm (Length × Width × Height). The side walls and ceiling were made of clear acrylic plastic, while the front and rear walls were made of brushed aluminum. A recessed food cup measured 5.1 cm × 5.1 cm and was centered on the front wall approximately 2.5 cm above the level of the floor. Two retractable levers (model ENV-112CM, Med Associates) were located on the front wall on either side of the food cup. The levers were 4.8 cm long and 6.3 cm above the grid floor. Levers protruded 1.9 cm from the front wall when extended. Directly across from each lever on the rear wall were chain pull and nose poke response manipulanda. The chain pull (14.5 cm long) was located 6.3 cm above the chamber floor near the opposite side wall, and the nose poke (2.5 cm in diameter and 2 cm deep) was located 6.3 cm (to center) above the chamber floor near the side panel that functioned as the chamber door. Four 28-V (2.8 W) panel lights (diameter = 2.5 cm) were mounted on the walls above (behind in the case of the chain) each response, 10.8 cm above the floor and 6.4 cm from the center of the front or rear wall. The chambers were illuminated by two 7.5 W incandescent bulbs mounted to the ceiling of the sound attenuation chamber, 34.9 cm from the grid floor, ventilation fans provided background noise of 65 dBA. The two sets of boxes had unique features that allowed them to serve as different contexts in other experiments but were not used for that purpose here. In one set of boxes, the grids of the floor were spaced 1.6 cm apart (center-to-center). In the other set of boxes, the floor consisted of alternating stainless steel grids with different diameters (0.5 and 1.3 cm, spaced 1.6 cm apart). There were no other distinctive features between the two sets of chambers. The reinforcer and control of events was the same as in Experiments 1 and 2.

Procedure

Training was conducted 7 days a week, with two sessions a day separated by approximately 3 hours. On the day prior to response training, rats received two sessions of magazine training in which they were trained to retrieve and consume food pellets from the food cup. Sessions consisted of 30 pellet deliveries according to a random-time 60-s schedule.

Individual chain training

Rats were then trained to perform each chain individually. Procurement responses consisted of chain pull or nose poke (counterbalanced) and consumption responses consisted of pressing the left or right levers (also counterbalanced). Individual chain training was conducted with only two manipulanda in the chamber at one time (one procurement and one consumption). Rats first learned to perform one of the consumption responses. In the first two sessions, there were 20 presentations of a consumption SD, separated by a variable 45-s ITI. If a consumption response was made within 60 s of stimulus onset, the stimulus turned off immediately and a pellet was delivered (CRF). Otherwise, the SD ended without a pellet after 60 s. In the next session, the procurement manipulandum (chain pull or nose poke) was introduced to the chamber and the first chain was trained. Procurement responses were counterbalanced such that half the rats were required travel along the side walls to reach the associated consumption response, and half had to cross the chamber diagonally. Single chain sessions consisted of 20 presentations of the procurement SD separated by a variable 45-s ITI. If a single procurement response was made within 60 s, the procurement SD terminated and the consumption SD was turned on, allowing the consumption response to be reinforced. Presentations of the procurement SD that did not lead to a procurement response ended after 60 s without the presentation of the consumption SD or a food pellet. Training of the first chain was conducted over six consecutive sessions. In the first two sessions, procurement and consumption responding were reinforced according to CRF (as described previously). On the final 4 sessions, the response requirement for procurement and consumption was RR 2. The second chain was then trained in an identical manner with the manipulanda used for the first chain removed from the chamber. As before, there were two sessions of training the consumption response and then 6 sessions of training the procurement-consumption chain.

Multiple chain training

Following training of the second chain, animals were trained to perform both chains in the same session. All four manipulanda were now present, and trials with the opportunity to perform each chain were presented in pseudo-random order. The response requirement for both procurement and consumption was initially reduced to CRF and increased to RR 4 over 8 sessions. The maximum stimulus durations that were allowed when there was no response were decreased from 60 s to 20 s. There were 40 chain trials in each session (20 with each chain). In addition, probe trials were added after every tenth trial. A probe trial consisted of the presentation of one of the procurement stimuli; when the response requirement (or 20 s stimulus) was met, both consumption SDs were presented simultaneously. A single correct consumption response, defined as a response to the lever associated with the probed procurement response, was immediately reinforced. A response to the wrong consumption manipulandum had no scheduled consequences. Probe trials ended without reinforcement if a correct response was not made before 60 s had elapsed. Probe trials provided a measure of whether the animals followed the chained structure of the task, as opposed to merely tracking the different SDs. Rats received 10 sessions of training with the terminal schedule parameters (RR 4 in all links on both chains). Sessions lasted approximately 40 min.

Extinction

Following acquisition, the rats were assigned to two groups. One group received 3 sessions of extinction training with one procurement response (Group Extinguished). The selected procurement response was fully counterbalanced for parallel/diagonal, nosepoke/chain, and position in the order in which the response sequence was initially trained. There were 40 presentations of the procurement stimulus in each session separated by a 45-s ITI. Except for the procurement manipulandum, all manipulanda were removed from the chamber. The remaining rats (Group Handle) received handling and transport in the same manner as the extinguished group, but were returned to the colony instead of being placed into the chamber for extinction.

Consumption test

All rats then received a test session in which each consumption response was tested in the presence of each consumption stimulus. Both consumption manipulanda were present in the chamber. The procurement manipulanda were absent. The test session consisted of 12 presentations of each consumption SD in an ABBA or BAAB order (counterbalanced). Consumption responses during a consumption SD turned off the stimulus according to RR 4, but did not produce food. Consumption SDs were otherwise terminated after 20 s on each trial.

Results

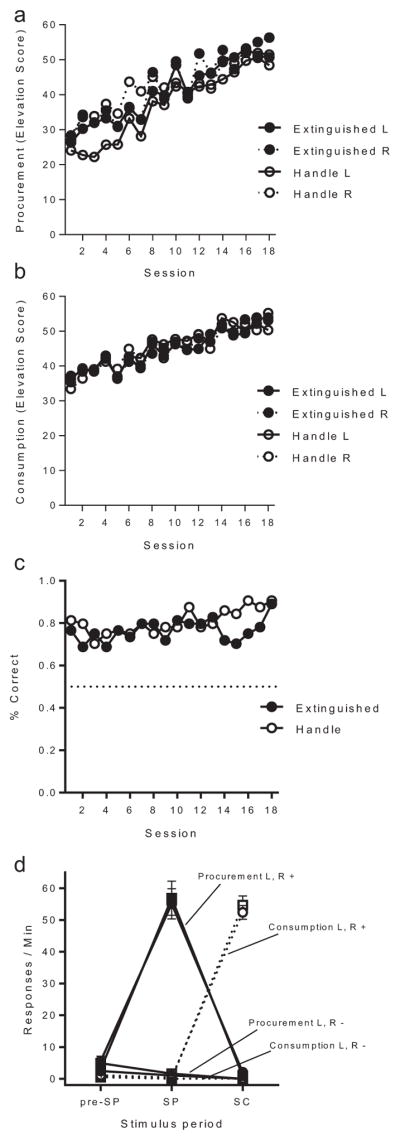

Acquisition

All rats acquired both chains. Figure 5 presents acquisition data for each chain. Consumption responses on the left and right levers and procurement responses that led to the left and right levers (nosepoke and chain, counterbalanced) are shown separately. (Focusing on L and R was a convenient way to distinguish between each animal’s two chains; recall that the various manipulanda were counterbalanced.) Figure 5a presents procurement responding as an elevation score. Each group (Extinguished and Control) increased procurement responding over training and procurement responses that led to left and right levers (L and R) were similar. Statistical analysis of acquisition was restricted to the final 10 sessions in which the final training parameters were in effect. Procurement responding in each group for each response was compared in a Group (Extinguished vs. Control) × Response (L vs. R) × Session (10) ANOVA. Responding increased across sessions, F(9, 270) = 8.27, MSE = 169.36, p < .001, η2 = .22, 95% CI [.11, .27], and there were no other differences or interactions, Fs < 1. Average procurement response rates during the preprocurement SD period were 2.8 and 4.1, 2.4 and 1.9 on the first RR 4 session, and 5.6 and 5.5, and 3.4 and 2.5 in Groups Extinguished and Handle on procurement responses L and R, respectively. A Group × Response × Session ANOVA revealed an increase in procurement responding during preprocurement SD periods, F(9, 270) = 4.42, MSE = 6.34, p < .001, , 95% CI [.04, .18], but no other significant effects or interactions, largest F = 1.46, MSE = 253.50.

Figure 5.

Acquisition of responding in Experiment 3. (a) Procurement response rate elevation scores, L and R refer to procurement responses that led to a left or right lever consumption response, respectively. (b) Consumption response rate elevation scores for left (L) and right (R) levers, respectively. (c) Accuracy (percent correct) on probe trials during acquisition. (d) Average response rate on each manipulandum in preprocurement, procurement, and consumption discriminative stimuli periods (preprocurement [Pre-SP], procurement [SP], and consumption [SC], respectively) collapsed over group. L and R refer to the different chains with left and right lever consumption manipulanda, respectively, “+” and “−” refer to response rates in reinforced and nonreinforced trials, respectively. Error bars are the SEM, and only appropriate for between-groups visual comparisons.

Consumption responding (Figure 5b) also increased over sessions and groups did not differ in responding on either lever. A Group (Extinguished vs. Control) × Response (L vs. R) × Session (10) ANOVA confirmed the effect of Session, F(9, 270) = 4.68, MSE = 132.47, p < .001, , 95% CI [.04, .18], and found no differences or interactions with session, Fs < 1. Average consumption response rates during the preprocurement SD period were 0.3 and 0.5, 0.5 and 0.3 on the first RR 4 session, and 0.3 and 0.3, and 0.5 and 0.7 in Groups Extinguished and Handle on consumption responses L and R, respectively. A Group × Response × Session ANOVA found no differences in consumption during preprocurement SD periods, largest F(1, 30) = 1.21.

Results of the probe trials are presented in Figure 5c. The first consumption response on each probe trial served as a measure of accuracy of responding in the chains. If the first response after consumption stimuli onset was to the consumption lever that was being trained in the specific chain, then the trial was counted as correct. Trials in which the first response was to the other lever were counted as incorrect. It is clear that the rats chose the correct response most of the time. Percent correct over the final 10 sessions of training was compared in a Group (Extinguished vs. Control) × Session (10) ANOVA. Overall accuracy in each group was always high, but a marginal effect of block, F(9, 558) = 1.76, MSE = 0.06, p = .07, suggested that accuracy may have nonetheless increased over blocks. Groups did not differ in their accuracy, and there was no Group × Block interaction, largest F = 1.39.

Figure 5d shows procurement and consumption response rates during the preprocurement, procurement, and consumption stimulus periods in the final session of acquisition. Once again, there was evidence of excellent stimulus control. Neither Group nor Chain factors differed across sessions of acquisition, therefore separate Response (procurement vs. consumption) × Status (reinforced chain vs. nonreinforced chain) ANOVAs for each stimulus period were applied to response rates collapsed over Group and Chain factors. In preprocurement, procurement responding was higher than consumption responding, F(1, 63) = 31.86, MSE = 19.84, p < .001, , 95% CI [.15, .48], and there were no effects of status or interaction, Fs < 1. In the procurement stimulus, procurement responding was also higher than consumption, F(1, 63) = 256.14, MSE = 203.37, p < .001, , 95% CI [.71, .85]. The procurement response associated with the reinforced chain was performed at a higher rate than that of the nonreinforced chain. This was confirmed by a significant status effect, F(1, 63) = 233.03, MSE = 206.76, p < .001, 95% CI [.69, .84], and a Response × Status interaction, F(1, 63) = 224.86, MSE = 210.07, p < .001, , 95% CI [.68, .84]. Similarly, there was significantly higher consumption responding than procurement responding in the presence of the consumption stimulus, F(1, 63) = 819.03, MSE = 53.05, p < .001, , 95% CI [.89, .95]. Effects of status, F(1, 63) = 852.95, MSE = 56.69, p < .001, , 95% CI [.90, .95], and a Response × Status interaction, F(1, 63) = 808.81, MSE = 53.49, p < .001, , 95% CI [.89, .95], further confirm strong discrimination of the reinforced chain in the presence of the consumption stimulus.

Extinction

Extinction of procurement responding in the Extinguished group proceeded without incident. Figure 6 summarizes the decline in procurement responding in each extinction session as a function of 4-trial blocks for procurement responses associated with either consumption response (L and R). A Response (L vs. R) × Block (10) × Session (3) ANOVA comparing within-session responding to each procurement stimulus across each session of extinction confirmed that responding decreased within each session, F(9, 126) = 24.00, MSE = 93.55, p < .001, , 95% CI [.50, .68], and across sessions, F(2, 28) = 13.58, MSE = 220.54, p < .01, , 95% CI [.18, .64]. A significant Session × Block interaction further confirmed that spontaneous recovery decreased across sessions of extinction, F(18, 252) = 4.93, MSE = 60.85, p < .001, , 95% CI [.12, .30], there were no other significant effects or interactions, Fs < 1. Average procurement response rates in the pre-SD period were 0.02 and 0.02 in the first session of extinction, and 0.02 and 0.01 in the last session for procurement responses 1 and 2, respectively. A Response × Block × Session ANOVA comparing procurement response rates during the preprocurement SD periods found no significant effects or interactions, largest F = 3.47, MSE = 0.005.

Figure 6.

Extinction of procurement in Experiment 3. Elevation scores of each Procurement response in 4-trial blocks across sessions of extinction. L and R refer to procurement responses that led to left- and right-lever consumption responses, respectively.

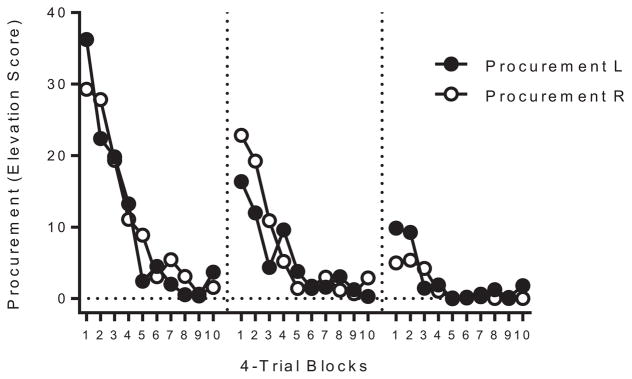

Consumption test

Consumption responding in Group Extinguished during the test session is presented as the solid lines in Figure 7. As suggested by the figure, the group responded less on the consumption lever that had been associated with the extinguished procurement response. This was confirmed by an ANOVA, which revealed a significant effect of response, F(1, 15) = 5.65, MSE = 52.98, p = .03, , 95% CI [.00, .54]. Responding also generally decreased across blocks, F(2, 30) = 52.98, MSE = 102.23, p < .001, , 95% CI [.59, .85], although there was no consumption Response × Block interaction, F < 1.

Figure 7.

Consumption test responding in Experiment 3. Consumption response elevation scores across blocks of 4 consumption discriminative stimuli presentations. Error bars are the SEM and only appropriate for interpreting between-groups comparisons.

To further assess the effect of procurement extinction on consumption responding, the two consumption responses in Group Extinguished were compared with responding in Group Handle, which had received no extinction treatment during the extinction phase. Group Handle’s averaged response rate is shown over trials in Figure 7 with broken lines. Group Extinguished’s extinction-associated response was significantly lower than responding in Group Handle, F(1, 30) = 8.04, MSE = 269.23, p < .01, , 95% CI [.02, .43]. ]. Consumption responding decreased across blocks, F(2, 60) = 59.03, MSE = 87.45, p < .001, , 95% CI [.51, .74], and the Consumption response effect did not interact with Block, F < 1. In contrast, Group Extinguished’s not-associated-with-extinction response did not differ from responding in Group Handle, F(1, 30) = 2.41, MSE = 276.54, p = .13, although it also decreased across blocks, F(2, 60) = 48.78, MSE = 112.55, p < .001, , 95% CI [.45, .71]. Finally, there were no group differences in preconsumption SD responding. Mean consumption response rates during the preconsumption SD period were 0.1 and 0.1 in the first block, and 0.02, and 0.02 in the last block for the consumption response associated with the extinguished procurement response in Group Extinguished and the average consumption response in Group Handle, respectively. A Group × Block ANOVA found a significant effect of block, F(2, 60) = 13.52, MSE = 0.007, p < .001, , 95% CI [.12, .46], and no effect of group or interaction, Fs < 1. For the nonextinguished consumption response in Group Extinguished, response rate during the preconsumption SD period was 0.2 in the first block of the consumption test, and 0.03 in the last. A Group × Block ANOVA found a significant effect of block, F(2, 60) = 15.95, MSE = 0.01, p < .001, , 95% CI [.15, .49], and no effect of group or interaction, largest F = 3.81, MSE = 0.012.

Discussion

The rats learned to perform two discriminated heterogeneous chains and demonstrated a high level of accuracy in choosing the correct consumption response after each procurement link during the probe tests. More important, in the experimental group, extinction of a procurement response selectively weakened the consumption response that had been associated with it during training. Moreover, procurement extinction did not measurably suppress the consumption response from the other chain, as suggested by comparison with responding in a control that received no extinction at all (Group Handle). The results thus suggest that procurement extinction can weaken consumption responding through a mechanism that does not reduce to response generalization or nonspecific effects such as frustration. The effect also cannot be explained by possible depression or inhibition of the animal’s representation of the reinforcer, which was common to both chains. The results are instead consistent with previous Pavlovian sequential compound conditioning studies that support a role for associatively based mediated extinction (Holland, 1990; Holland & Ross, 1981). In this case, the mediating link might be an association between a specific procurement response and a specific consumption response (or consumption response/SD combination).

General Discussion

The present experiments begin to characterize both extinction and the associative structure that underlies a discriminated heterogeneous instrumental chain. In all three experiments, extinction of a procurement response weakened subsequent performance of the consumption response that had followed it in a chain. Experiment 1 established this effect, and showed that extinction of the entire chain also weakened consumption responding. The results of Experiment 2 replicated the procurement extinction effect, and further demonstrated that making the procurement response played a necessary role in producing the effect; nonreinforced exposure to the procurement SD alone did not weaken the consumption response. The role of the response in extinction implied by that result may be consistent with previous work from this laboratory suggesting that learning to inhibit the response is especially important in instrumental extinction (Bouton et al., 2011; Todd et al., 2014). Experiment 3 then trained two separate discriminated heterogeneous chains and found that extinction of one of the two procurement responses selectively weakened the consumption response that had been associated with it. Rats performed the consumption response associated with the nonextinguished procurement response at a level that was not different from that in a control group that had received no procurement extinction (or even exposure to the conditioning chamber during extinction). The pattern argues strongly against explanations based on response generalization or on potential nonspecific effects of extinction (e.g., frustration). Instead, the results of Experiment 3 suggest that the effect of procurement extinction depended on the procurement response’s specific association with the consumption link that followed it in the instrumental training sequence.

In addition to demonstrating that animals associate the procurement and consumption links in discriminated chains, the present results suggest that responses in the chain can be influenced by mediated extinction (Holland, 1990). Mediated extinction has primarily been observed in conditioned taste aversion and appetitive Pavlovian serial compound conditioning paradigms. For example, Holland and Forbes (1982) gave rats a series of tone-sucrose pairings followed by sucrose paired with lithium chloride. Extinction presentations of tone alone, like sucrose alone, were then found to weaken rats’ aversion to the sucrose. Thus, extinction exposures to a stimulus that was associated the sucrose was sufficient to create extinction to it. Holland and Ross (1981) produced similar results in an appetitive conditioning preparation we described in the Introduction to Experiment 3. When rats were given a serial light-tone-food sequence during conditioning, extinction trials with the light alone effectively weakened responding to the tone. Additionally, in a within-subject experiment comparing two separate serial compounds (Holland & Ross, 1981, Experiment 3), the effect was found to be specific to the stimulus trained in serial compound with the extinguished stimulus. The authors suggested that serial compound training resulted in a light-tone association, and that presentations of the light alone in extinction resulted in the activation of a representation of the tone that allowed responding to it to be extinguished (cf., Holland, 1990; Holland & Wheeler, 2009). The present experiments clearly share several characteristics with the design and results reported by Holland and Ross (1981). They suggest that the procurement and consumption links within a discriminated heterogeneous chain can also become associated and allow mediated extinction to occur.

The results also make preliminary headway into identifying the parts of the discriminated chain that are crucially associated to enable mediated extinction. First, the results of Experiment 2 suggest that the animals needed to make the procurement response in order for consumption behavior to be weakened. Repeated exposure to the procurement SD alone, as well as its termination, were not sufficient to weaken consumption. Second, in the extinction phase of Experiment 2, we found that when the animal completed the procurement response requirement, it quickly made the consumption response in the absence of the consumption SD. Although the procurement response also terminated the procurement SD there, as just noted, mere exposure to that event alone was not sufficient to weaken consumption responding. Thus, the role of the procurement response itself may be more crucial. But what are the important events with which the procurement response is associated? The next events in the chain are the consumption SD, the consumption response, and the reinforcer. The specificity of the effect of procurement extinction to the consumption response it was chained with (Experiment 3) argues against the role of the procurement response’s association with the reinforcer: Both chains ended with the same food pellet, and any inhibition of the reinforcer representation therefore should have depressed both consumption responses equally. The present results may thus narrow the crucial association to either one between the procurement response and the consumption response, or between the procurement response and the consumption SD. It is notable, however, that the consumption SD had surprisingly limited power in the present method. Although it was effective at setting the occasion for the consumption response when the response was tested outside the chain (as demonstrated in the consumption tests in each experiment), it was not demonstrably effective as a conditioned reinforcer (Experiment 1), and as just noted, its presentation was not necessary to set the occasion for consumption responding (Experiment 2). Performing the procurement response appears to have been sufficient to do that. Although these observations suggest a somewhat limited role for the consumption SD in supporting behavior in the present discriminated chain, the performance of the procurement response in extinction could have nonetheless activated or retrieved either a representation of the consumption response or the consumption SD to enable the present mediated extinction effect.

To our knowledge, the present experiments are the first to assess the impact of procurement extinction on consumption responding. As noted earlier, previous work has focused on extinction of consumption as a means of devaluing the consumption response and then assessing whether procurement behavior is sensitive to that devaluation (Olmstead et al., 2001; Zapata et al., 2010). The present results extend those findings by showing that consumption behavior is conversely sensitive to extinction of the procurement response. The results of Experiment 2 also uniquely suggest that making the procurement response in extinction was important for weakening consumption. The role of the response (as opposed to simple exposure to the SD alone) has yet to be isolated when extinction of consumption behavior weakens procurement.

In terms of application, the present results begin to suggest that extinction-based treatments that inhibit procurement behavior might also reduce associated consumption responses when they are made available. As noted earlier, consumption responses are rarely really extinguished directly in the sense that it is unusual for a drug injector to inject herself without the drug, the smoker to smoke denicotinized cigarettes, or the junk food eater to make chewing and swallowing movements without introducing food to the mouth. The present results begin to suggest that learning to inhibit the purchase or procurement of drugs, cigarettes, or junk food might facilitate a decrease in consuming the substance when it is offered later. Of course, any such effect might require a tight coupling between the specific procurement and consumption responses, like that provided here. Interestingly, recent studies of extinction exposure in smokers have targeted distal stimuli that might not be directly associated with actual consumption and shown that these stimuli evoke craving in a similar manner to more proximal stimuli (Conklin, Robin, Perkins, Salkeld, & McClernon, 2008).

In sum, the present experiments are the first to demonstrate that a decrement in consumption behavior can be produced by extinction of an associated procurement behavior in a discriminated heterogeneous instrumental chain. This decrement appears to be a result of learning about the procurement response, and is specific to a consumption response specifically associated with the extinguished procurement response. The specificity of the effect suggests that inhibition of procurement has the effect of weakening the consumption response through representation-mediated extinction. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of mediated extinction of instrumental behavior. Finally, the present results have practical application for clinicians seeking to identify efficient treatment targets for reducing problem behaviors such as drug abuse and overeating. To the extent that such behaviors are part of a discriminated heterogeneous chain like the one investigated here, suppression of a late part of the chain might benefit from extinction of an earlier part of the chain.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant RO1 DA033123 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Mark E. Bouton. We thank Joseph Carpenter, Scott Schepers, Sydney Trask, and Jeremy Trott for comments on the manuscript.

References

- Amsel A. Frustrative nonreward in partial reinforcement and discrimination learning: Some recent history and a theoretical extension. Psychological Review. 1962;69:306–328. doi: 10.1037/h0046200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0046200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balleine B. Instrumental performance following a shift in primary motivation depends on incentive learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1992;18:236–250. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0097-7403.18.3.236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balleine BW, Garner C, Gonzalez F, Dickinson A. Motivational control of heterogeneous instrumental chains. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1995;21:203–217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0097-7403.21.3.203. [Google Scholar]