Abstract

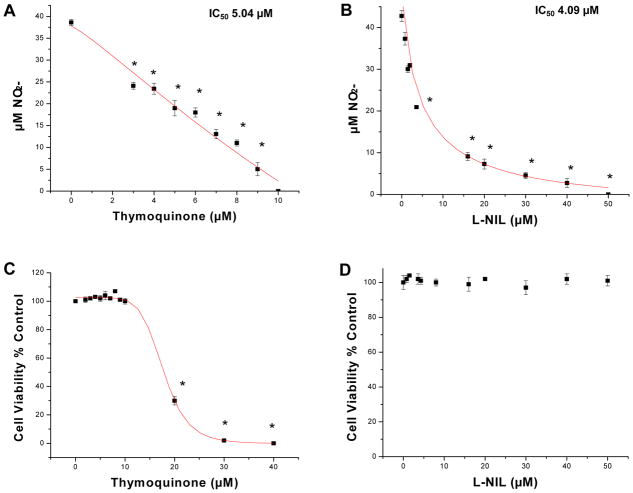

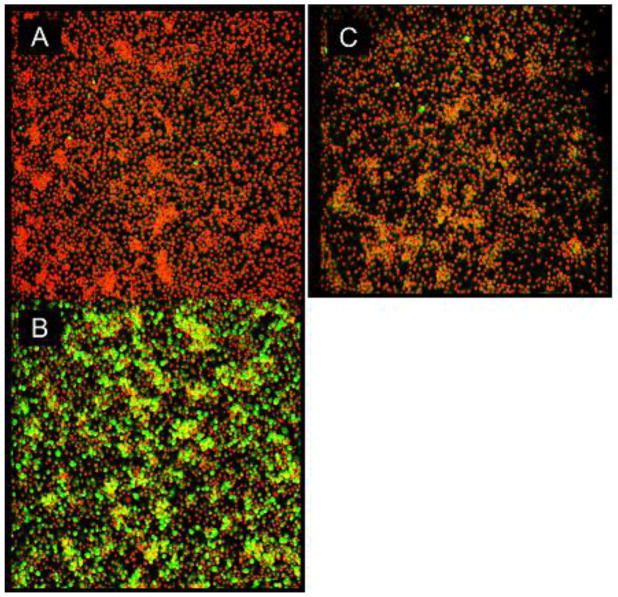

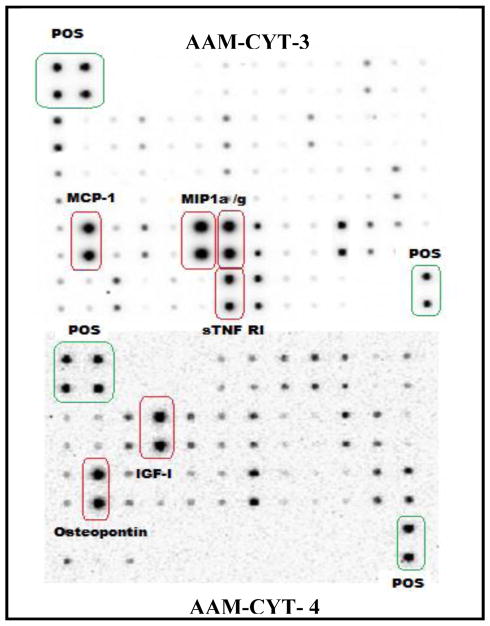

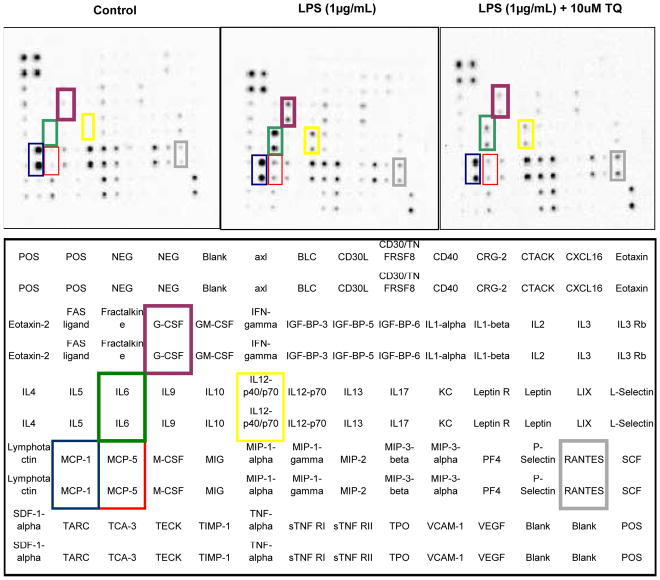

Thymoquinone (TQ), the main pharmacological active ingredient within the black cumin seed (Nigella sativa) is believed to be responsible for therapeutic effects on chronic inflammatory conditions such as arthritis, asthma and neurodegeneration. In this study, we evaluated the potential anti-inflammatory role of TQ in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated BV-2 murine microglia cells. The results obtained indicated that TQ was effective in reducing NO2- with an IC50 of 5.04 μM, relative to selective iNOS inhibitor LNIL- L-N6-(1-Iminoethyl)lysine (IC50 4.09 μM). TQ mediated reduction in NO2- was found to parallel the decline of iNOS protein expression as confirmed by immunocytochemistry. In the next study, we evaluated the anti-inflammatory effects of TQ on ninety – six (96) cytokines using a RayBio AAM-CYT-3 and 4 cytokine antibody protein array. Data obtained establish a baseline protein expression profile characteristic of resting BV-2 cells in the order of osteopontin > MIP-1alpha > MIP-1g > IGF-1 and MCP-I. In the presence of LPS [1ug/ml], activated BV-2 cells produced a sharp rise in specific pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokine’s IL-6, IL-12p40/70, CCL12 /MCP-5, CCL2 / MCP-1, and G-CSF which were attenuated by the addition of TQ (10μM). The TQ mediated attenuation of MCP-5, MCP-1 and IL-6 protein in supernatants from activated BV-2 cells were corroborated by independent ELISA and mRNA expression profiling using RT2 Profiler PCR cytokine arrays. Moreover, the data obtained from the RT2 PCR demonstrated a similar pattern where the LPS mediated elevation of mRNA for IL-6, CCL12 /MCP-5, CCL2 / MCP-1 were significantly attenuated by TQ (10μM). Also, in this study, consistent data were obtained for both protein antibody array densitometry and ELISA assays. In addition, TQ was found to reduce LPS mediated elevation in gene expression of Cxcl10 and a number of other cytokines in the panel. These findings demonstrate the significant anti-inflammatory properties of TQ in LPS activated microglial cells. Therefore, the obtained results might indicate the usefulness of TQ in delaying the onset of inflammation-mediated neurodegenerative disorders involving activated microglia cells.

Keywords: cytokines, nitric oxide, microglial cells, Parkinson’s, neurodegeneration, thymoquinone, black cumin seed

Introduction

Chronic low grade central nervous system (CNS) neuro-inflammation is a pathological component of many degenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Shivers et al., 2014), Alzheimer’s (AD) (Sacino et al., 2014) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Rizzo et al., 2014). The presence of activated microglia and glial cells circumscribe necrotic neuronal debris associated with diverse types of inflammatory brain injury (Gyoneva et al., 2014, Ramsey and Tansey, 2014, Russo et al., 2014), which reciprocally exacerbate neurodegenerative processes in a cyclical fashion.

For centuries, particularly in the Middle East, black cumin seeds (Nigella sativa) have been used to treat a diverse range of peripheral and central inflammatory related illnesses such as diabetes, asthma, arthritis, colitis, periodontitis and encephalomyelitis (Butt and Sultan, 2010, Padhye et al., 2008, Sankaranarayanan and Pari, 2011, Shabana et al., 2013, Woo et al., 2012). Moreover, unlike some synthetic drugs, the anti-inflammatory properties of black cumin seeds are accompanied by a milieu of health promoting effects on almost every major system (i.e. cardiovascular, respiratory, immune) (Padhye, Banerjee, 2008) and organ (i.e. digestive tract, kidney, pancreas and liver) of the human body (Ahmad et al., 2013, Alkharfy et al., 2011, Basarslan et al., 2012, Nili-Ahmadabadi et al., 2011, Sankaranarayanan and Pari, 2011).

With advances in biomedical sciences, we now know that the anti-inflammatory effects of black cumin seed on health are largely attributable to its primary active component; thymoquinone (TQ) (Ali and Blunden, 2003). TQ possesses a number of pharmacological therapeutic values with respect to CNS neuroinflammation including its inherent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory (Gilhotra and Dhingra, 2011, Idris-Khodja and Schini-Kerth, 2012, Mansour et al., 2002, Tesarova et al., 2011) and neuroprotective properties (Mohamed et al., 2003) evidenced in diverse models of injury such as multiple sclerosis, (Mohamed et al., 2005) forebrain ischemia-reperfusion injury, (Al-Majed et al., 2006, Hosseinzadeh et al., 2007) ethanol-induced or heavy metal neurodegeneration. (Radad et al., 2014, Ullah et al., 2012)

The ability of TQ to block NF-kappaB activation and its molecular targets (Kundu et al., 2013, Xuan et al., 2010) can account for much of its anti-neuroinflammatory effects which are strengthened by ability to attenuate cytokines including TNF-alpha, IL-1beta (Tekeoglu et al., 2007), nitric oxide (NO) / iNOS, IL-6, IFN-gamma, prostaglandin E2 (Umar et al., 2012), TGF-beta1 (Ammar el et al., 2011), 5-lipoxygenase activity (Landa et al., 2013) and cyclooxygenase-2 (Salem, 2005, Yang et al., 2012). Heightened biological activity of these processes are associated with age related neurodegenerative diseases often perpetuated by chronic CNS inflammation via resident macrophages in the brain; glial/ microglia cells (Batool et al., 2013, Furusawa et al., 2009, Hirai et al., 2007, Wong, 2013).

While several studies have demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects of TQ in LPS activated macrophages (Wilkins et al., 2011), there are meager studies evaluating for the effects of TQ on microglia / glial cell immunological response. In this study, we evaluate the propensity of TQ to inhibit LPS activated BV2 microglial cells relative to a known control, selective iNOS inhibitor N6-(1-iminoethyl)-L-lysine, dihydrochloride L-NIL.

Methods and Materials

Hanks Balanced Salt Solution, (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) (HEPES), ethanol, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 96 well plates, general reagents and supplies, were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO), and VWR International (Radnor, PA). Imaging probes were supplied by (Life Technologies Grand Island, NY). All Chemicals and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company Inc., Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Cell Culture

BV-2 microglial cells were kindly provided by Elizabeta Blasi (Blasi et al., 1990). Cells were cultured in DMEM media containing 5% FBS, 4 mM L-glutamine, and penicillin/streptomycin (100 U /0.1 mg/ml). Culture conditions were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2/atmosphere and every 2–3 days, the media was replaced and cells sub-cultured. For performing each experiment, plating media consisted of DMEM (minus phenol red), 2.5% FBS and no penicillin/streptomycin. L-N6-(1-Iminoethyl)lysine (L-NIL) and thymoquinone (TQ) were dissolved in DMSO [20mg/ml] and dilutions were prepared in sterile HBSS + 5 mM HEPES, adjusted to a pH of 7.4. Activation of BV-2 cells was established using 1μg/ml of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli 0111:B4.

Cell Viability

Cell viability was assessed using resazurin (Alamar Blue) indicator dye (Evans et al., 2001). Approximately 0.5 × 105 cells/ml (100μl per well) were plated in 96 well plates over night. The next day cells were first stimulated with 1μg/mL LPS for 1 hr then treated with different concentrations (0–100μM) TQ and incubated at 37°C for 24 hr. Following the desired time points, 20μl of Alamar blue solution (0.5 mg/ml) was added and incubated again for another 6 hr. The florescent signal was monitored using 485 nm excitation and 590 nm emission wavelengths using a microplate fluorometer, Model 7620, version 5.02 (Cambridge Technologies Inc, Watertown, MA). The fluorescent and colorimetric signal generated from the assay is proportional to the number of living cells in the sample. The data were expressed as percent of live untreated controls.

Nitrite (NO2–)/ iNOS Assay

Quantification of nitrite (NO2–) was determined by using the Greiss reagent. The Greiss reagent was prepared by mixing an equal volume of 1.0% sulfanilamide in 0.5 N HCl and 0.1% N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine in deionized water. The Griess reagent was added directly to the cell supernatant suspension and incubated under reduced light at room temperature for 10 min. A standard curve for NO2– was generated from dilutions of sodium nitrite (NaNO2) (1–100 μM) prepared in plating medium. Controls and blanks were run simultaneously, and subtracted from the final value to eliminate interference. Samples were analyzed at 550 nm on a UV microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Wincoski, VT, USA).

For iNOS protein expression, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/ permeabilized in 0.1% triton X 100 in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with anti-iNOS, N-Terminal antibody produced in rabbit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 2 hours at 37°C. Samples were washed in PBS and subsequently incubated with anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor® 488 conjugate for two hours at 37°C. Samples were counterstained with propidium iodide and photographically using a Nikon TE 900 inverted microscope, Nikon PCM 2000 confocal microscope and data acquisition using C-imaging systems confocal PCI-Simple software (Compix Inc. Cranberry Township, PA, USA).

Mouse Cytokine Antibody Array

RayBiotech Mouse Cytokine Antibody Array (Cat# AAM-CYT-1000) was used to profile the effect of TQ on 96 (in duplicate) cytokine proteins. Each experiment was carried out in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, antibody- coated array membranes were first incubated for 30min with 1 ml of blocking buffer. After 30min, blocking buffer was decanted and replaced with 1ml supernatant from control (untreated) samples treated with (1ug/ml LPS only, 10 μM TQ only, 10 μM TQ + 1ug/ml LPS). Membranes were allowed to incubate overnight at 4°C with shaking. The next day, the medium was decanted, the membranes were washed with washing buffer and then incubated with 1 ml biotin-conjugated antibodies (overnight 4°C with shaking). Mixture of biotin-conjugated antibodies was removed and membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated streptavidin (2hrs). Detection of spots using chemiluminescence was acquired with semi-quantitative analysis of signal intensities from Quantity One software. Intensities were normalized as a percentage of positive controls on each membrane.

Cytokine ELISAs

Murine Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) (Catalog # ELM-MCP1-001), Monocyte chemoattractant protein-5 (Catalog # ELM-MCP5-001) and IL-6 (Cat#: ELM-IL6-001C) quantitative ELISAs (Raybio ®) were used for detection and quantification of specific cytokines produced /released. Experiments were performed according to the manufacturer’s guidelines and quantified at 450 nm (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Wincoski, VT, USA).

RNA Extraction and PCR Array

Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy Mini extraction kit (Qiagen, Cat# 74104) and then first-strand cDNA was synthesized using RT2 first Strand Kit(Qiagen, Cat.# 330401) following the manufacturer protocol. PCR amplification was performed using RT2 SYBR Green Fluor PCR Mastermix (Qiagen, Cat. # 330510). From each sample 25 μl PCR product was used to run the RT2 Profiler PCR array (Qiagen, PAMM-150A-2) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The PCR thermal cycling programs were first denaturation 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1min. Data analysis was performed using RT2 Profiler PCR array data analysis on line software (http://www.sabiosciences.com/pcrarraydataanalysis.php).

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism (version 3.0; Graph Pad Software Inc. San Diego, CA, USA) with significance of difference between the groups assessed using a one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey post hoc means comparison test, or Student’s t test. IC50s were determined by regression analysis using Origin Software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA).

Results

Preliminary studies were conducted to establish an optimum dose of LPS to induce maximum NO2- after 24 hours, which was determined to 1μg/mL (data not shown). The anti-inflammatory effects of TQ were demonstrated by a reduction of NO2- in activated BV-2 cells (Fig. 1A) at sub-lethal concentrations [<10μM] (Fig. 1C), with comparable potency to the iNOS inhibitor control - L-NIL (Fig. 1B) – which was not toxic at concentrations up to 50μM (Fig. 1D). The effects of TQ in the attenuation of NO2- from activated BV-2 cells corresponded to reduction of iNOS protein expression as confirmed by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

A–D. The effects of TQ relative to L-NIL on reducing NO2- production in LPS activated BV-2 microglial cells. The data represents μM NO2- produced (A,B) and cell viability (C,D) as % untreated control (HBSS), both are expressed as the Mean ± S.E.M., n=4. Statistical differences between the HBSS untreated control groups (zero uM) vs. treatments were evaluated by a one-way ANOVA, followed by a Tukey post hoc test, * p<0.05.

Fig. 2.

Effect of TQ on iNOS protein expression. BV2 cells were permeabilized and immunocytochemistry was conducted with anti-iNOS, N-Terminal antibody produced in rabbit conjugated to goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor®488 (green) / and nuclear counterstained with PI (red). A= Control B= LPS [1μg/mL] C= LPS + TQ (10μM).

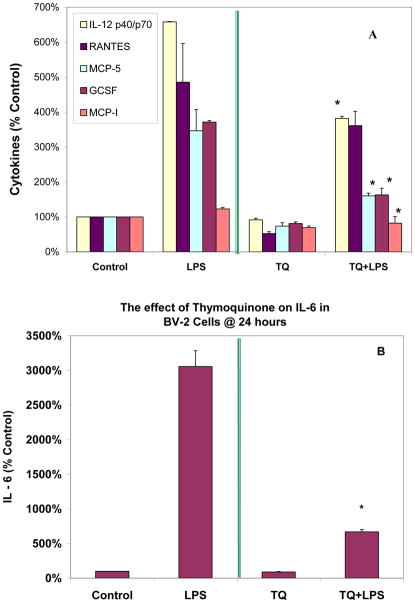

In order to establish a baseline profile of cytokine production in resting BV-2 cells, a RayBio AAM-CYT-3 & 4 murine cytokine array was utilized to assess quantity of pro-inflammatory molecules (Fig. 3 ). The data showed predominant expression and release of osteopontin > MIP-1α (CCL3) > MIP-1γ (CCL9) > IGF-1 and MCP-1(CCL2). Most of these proteins are reportedly highly expressed by microglia, possibly exerting a role in glial proliferation (Tambuyzer et al., 2012), neuroprotection (Brown, 2012) and CNS inflammatory processes (Lu et al., 2013). Relative to resting cells, LPS actived BV-2 cells produced greater levels of IL-6, MCP-5 (CCL12), MCP-1 (CCL2), IL-12 p40/p70, GCSF and CCL5/ RANTES (Fig. 4), all of which were reduced by TQ (Fig. 5A,B).

Fig. 3.

Cytokine expression in BV-2 resting microglial cells.

Fig. 4.

Cytokine expression in treated microglia cells; control vs. LPS (1μg/mL) vs. LPS (1μg/mL) + TQ (10μM) and showing corresponding membrane identification chart (Bottom) and membrane images (Top).

Fig. 5.

The effect of TQ (10μM) on resting and LPS (1μg/mL) treated BV-2 microglia cells. The data represent protein expression of cytokines (A) and IL-6 (B) as normalized intensity, expressed as % controls arrays (n=6 arrays) as Mean ± S.E.M.. Statistical Differences from the control vs TQ and LPS vs LPS + TQ were evaluated by a students t-test, * p<0.05.

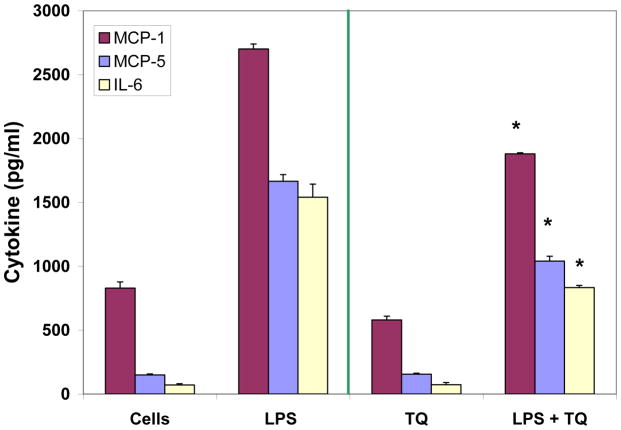

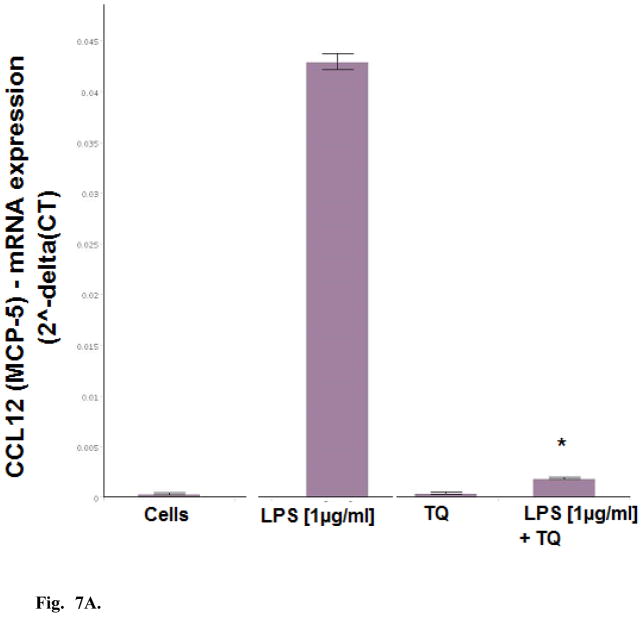

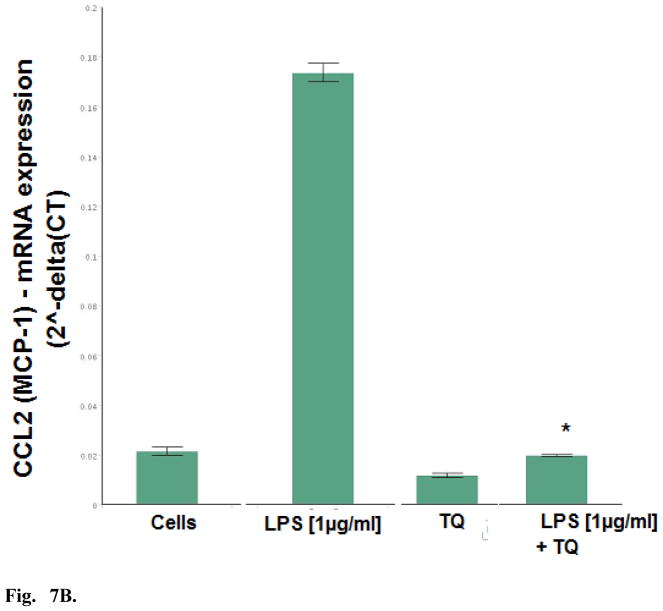

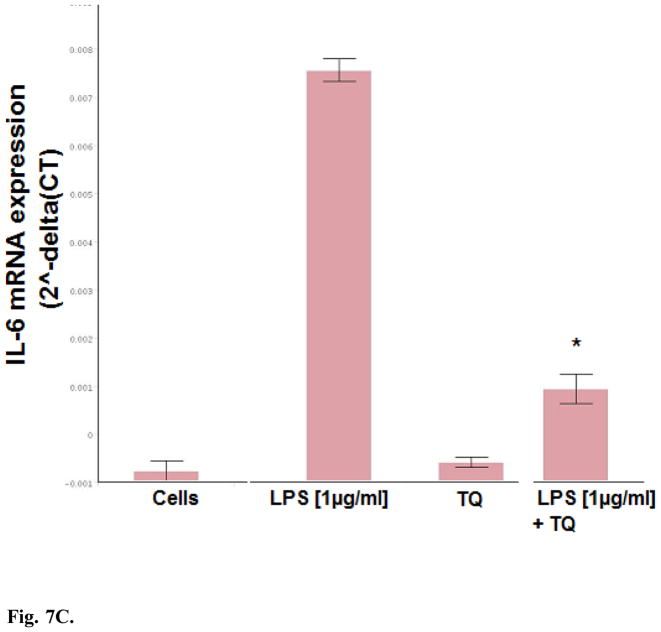

Dual detection methods were used to corroborate the anti-inflammatory effects of TQ using individual ELISAs, where effects of TQ were found to attenuate LPS induced MCP-1, MCP-5, and IL-6 (Fig. 6). Evaluation of mRNA expression on a panel of cytokines was also investigated using RT2 Profiler PCR PAMM-150, (Table 1.) setting criteria cut off values at P <0.05 (between control and LPS / and LPS and TQ + LPS groups), fold change > 3 and CT count in LPS treated cells <35 to reduce changes near the limit of detection. The shift in the genomic values were consistent with protein data and showed TQ mediated reduction in expression profiles for MCP-1, MCP-5 and IL-6 by TQ (Fig. 7A–C). These findings establish general anti-inflammatory effects of TQ in microglia cells.

Fig. 6.

Effect of TQ (10μM) on MCP-1, MCP-5 and IL-6 protein release in resting and LPS stimulated BV-2 microglia cells. The data represent cytokine [pg/ml] released and are expressed as the Mean ± S.E.M., n=4. Statistical differences from the LPS vs LPS +TQ treated were evaluated by a students t-test, * p<0.001.

Table 1.

Effect of LPS alone and LPS ± TQ on cytokine expression profile of BV 2 cells, criteria cut off values P <0.05 (between control and LPS / and LPS and TQ LPS), fold change > 3 and CT count in LPS treated cells <35.

| Control vs LPS (BV2 Cells) | LPS vs TQ + LPS (BV2 Cells) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Well | Direction | FOLD CHANGE LPS/ Control | P-Value | Direction | FOLD CHANGE LPS + TQ / Control | P-Value | FOLD CHANGE LPS / LPS + TQ | P-Value |

| Ccl12 | A08 | ▲ | 195.99 | <.001 | ▼ | 8.39 | 0.000 | −23.350 | <.001 |

| Ccl2 | A11 | ▲ | 8.06 | <.001 | ▼ | −1.09 | 0.142 | −8.807 | <.001 |

| Ccl22 | B01 | ▲ | 23.56 | 0.005 | ▼ | 17.70 | 0.007 | −1.331 | 0.004 |

| Ccl3 | B03 | ▲ | 4.15 | <.001 | ▼ | 2.72 | 0.001 | −1.525 | <.001 |

| Ccl4 | B04 | ▲ | 15.40 | <.001 | ▼ | 1.51 | 0.000 | −10.211 | <.001 |

| Ccl5 | B05 | ▲ | 696.83 | <.001 | ▲ | 854.73 | 0.000 | 1.227 | 0.001 |

| Ccl7 | B06 | ▲ | 7.13 | <.001 | ▼ | −5.56 | 0.000 | −39.634 | <.001 |

| Cd70 | B08 | ▲ | 31.52 | 0.001 | ▼ | 18.89 | 0.001 | −1.669 | <.001 |

| Cxcl10 | C04 | ▲ | 638.26 | 0.002 | ▼ | 112.41 | 0.003 | −5.678 | 0.104 |

| Cxcl16 | C08 | ▲ | 7.49 | <.001 | ▼ | 2.80 | 0.002 | −2.673 | <.001 |

| Cxcl3 | C09 | ▲ | 43.75 | <.001 | ▼ | 30.19 | 0.000 | −1.449 | 0.004 |

| Cxcl9 | C11 | ▲ | 10.76 | 0.031 | ▼ | 5.87 | 0.073 | −1.834 | <.001 |

| Il12b | D08 | ▲ | 29.54 | 0.014 | ▼ | 11.57 | 0.068 | −2.553 | 0.359 |

| Il15 | D10 | ▲ | 4.84 | <.001 | ▼ | 3.56 | 0.000 | −1.358 | 0.001 |

| Il1a | E03 | ▲ | 5.23 | <.001 | ▲ | 7.81 | 0.000 | 1.493 | <.001 |

| Il1b | E04 | ▲ | 34.81 | 0.002 | ▼ | 9.91 | 0.012 | −3.511 | <.001 |

| Il1rn | E05 | ▲ | 4.72 | 0.001 | ▼ | 4.04 | 0.002 | −1.166 | 0.040 |

| Il23a | E09 | ▲ | 3.72 | 0.001 | ▼ | 3.32 | 0.001 | −1.121 | 0.076 |

| Il27 | E11 | ▲ | 12.48 | <.001 | ▼ | 6.09 | 0.001 | −2.050 | <.001 |

| Il6 | F03 | ▲ | 623.68 | <.001 | ▼ | 139.68 | 0.000 | −4.465 | <.001 |

| Il7 | F04 | ▲ | 14.94 | 0.013 | ▼ | 8.95 | 0.028 | −1.669 | 0.035 |

| Lif | F06 | ▲ | 16.73 | <.001 | ▲ | 41.82 | 0.000 | 2.499 | <.001 |

| Lta | F07 | ▲ | 30.65 | <.001 | ▲ | 53.54 | 0.000 | 1.747 | <.001 |

| Tnf | G06 | ▲ | 23.02 | <.001 | ▼ | 17.58 | 0.000 | −1.309 | <.001 |

| Tnfsf10 | G08 | ▲ | 49.11 | 0.002 | ▼ | 40.58 | 0.003 | −1.210 | 0.013 |

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7A. Effect of TQ (10μM) on CCL12 /MCP-5 mRNA expression in resting and LPS stimulated BV-2 microglia cells determined using RT2 Profiler PCR Arrays. The data represent CCL12 /MCP-5 [fold change from Cells (Control)] and are expressed as the Mean ± S.E.M., n=4. Statistical differences from the LPS control vs LPS TQ treated were evaluated by a students t-test, * p<0.001.

Fig. 7B. Effect of TQ (10μM) on Ccl2 / MCP-1 mRNA expression in resting and LPS stimulated BV-2 microglia cells determined using RT2 Profiler PCR Arrays. The data represent Ccl2 / MCP-1 [2^-delta(CT)] and are expressed as the Mean ± S.E.M., n=3. Statistical differences from the LPS control vs LPS TQ treated were evaluated by a students t-test, * p<0.001.

Fig. 7C. Effect of TQ (10μM) on IL-6 mRNA expression in resting and LPS stimulated BV-2 microglia cells determined using RT2 Profiler PCR Arrays. The data represent IL-6 [2^-delta(CT)] and are expressed as the Mean ± S.E.M., n=3. Statistical differences from the LPS control vs LPS TQ treated were evaluated by a students t-test, * p<0.001.

Discussion

The data obtained in this study provide information on baseline cytokine profile of [1] resting BV-2 microglial cells, [2] cytokines and chemokines induced by LPS in activated microglia and [3] the anti-inflammatory effects of TQ on these systems. In resting BV-2 cells, osteopontin was the highest protein expressed, which could be a function of immortality as it is consistently reported in aggressive malignant glioblastomas (Jang et al., 2006, Matusan-Ilijas et al., 2008), in cerebrospinal fluid samples from glioma cancer patients (Yamaguchi et al., 2013) and its concentration is associated with invasiveness potential (Jan et al., 2010). Although very little is known about a role of osteopontin in primary microglia cells, it has been suggested to be a contributing factor to protection of nigral dopaminergic neurons somehow involving integrin and CD44 receptor interactions that promote neuronal remodeling (Hasegawa-Ishii et al., 2011, Liao et al., 2011) and survival (Del Rio et al., 2011). In this study, its quantity did not vary with LPS activation indicating its function is likely not related to inflammation.

Resting BV-2 cells also exhibited a high baseline expression of three major chemokines ; MIP-1α (CCL3) > MIP-1g (CCL9) > and MCP-I (CCL2) all of which are elevated in CNS disease, trauma (Kochanek et al., 2013, Rhodes et al., 2009), excitotoxic neurodegeneration (Okamura et al., 2012), MPTP damage to dopaminergic neurons (Kalkonde et al., 2007) and in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (Liao, Guan, 2011). In AD models, MIP-1α can activate astrocytes and microligal cells associated with Abeta (1–40) damage to the hippocampus, suggesting a primary role in neurodegeneration (Passos et al., 2009). While the presence of these proteins were abundant in resting microglia cells, the findings from this study show the LPS mediated rise of a diverse set of cytokines including IL-6, IL-1β, IL-12p40/70, (CCL12)/MCP-5, (CCL2)/MCP-1, GCSF, and Cxcl 10/IP-10 all of which were reduced by TQ. Typically, most all of these pro-inflammatory markers are commonly observed in neurodegenerative conditions such as neuromyelitis optica, multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury, (Uzawa et al., 2010) with chemokines such as MIP-2, MCP-1 being released in the area of degenerative neurons (Rhodes, Sharkey, 2009).

These findings are somewhat in alignment with previous reports investigating LPS activation in microglial cells, in particular for elevation of MIP-2, TNF-alpha, IL-1a, IL-6, MIP-1a, MCP-1 and GCSF, NO, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (Soliman et al., 2013) where others report elevation of additional pro-inflammatory markers such as free radicals, osteopontin (Hasegawa-Ishii, Takei, 2011, Mayer et al., 2011), IL-1beta (Ye et al., 2013), PGE2 (Kim et al., 2013b) and increased the levels of cyclooxygenase (Cox) 1 and 2 (Soliman, et al 2013). In general pro-inflammatory processes associated with activated BV-2 microglial cells involved a number of signaling pathways that involve Src-MEK1/2-ERK1/2 (Manivannan et al., 2013, Yeh et al., 2013) p38MAPK phosphorylation (Kim et al., 2013a), phosphorylation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase and the nuclear translocation of NF-kappaB p65 (Jung et al., 2013, More et al., 2013) /activation of NFkappaB-signaling pathway (Yeh, Yang, 2013) or down-regulation of HO-1 / and PKA-mediated CREB phosphorylation.(Park et al., 2012) Future studies will be required to further corroborate these signaling pathways to be involved with the anti-inflammatory effects of TQ.

In conclusion, these findings suggest a general anti-inflammatory effect of TQ on activated microglia to involve attenuation of cytokines, NO, iNOS which could provide therapeutic value different neurodegenerative diseases (Dariani et al., 2013, Ullah, Ullah, 2012).

Highlights.

The anti-inflammatory role of thymoquinone (TQ) in microglia were investigated.

TQ reduced LPS induced NO2- and corresponding iNOS protein expression.

TQ reduced LPS induced IL-6,MCP-5, MCP-1 and G-CSF protein expression.

TQ reduced LPS induced IL-6,MCP-5, MCP-1 and G-CSF mRNA transcription.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health through Grant Number 8 G12MD007582-28 and Grant Number 1P20 MD006738-01. We would like to also thank Elizabetta Blast (Department of Experimental Medicine and Biochemical Sciences, University of Perugia, Italy) for providing the BV-2 microglia cell line.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

N/A

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmad A, Husain A, Mujeeb M, Khan SA, Najmi AK, Siddique NA, et al. A review on therapeutic potential of Nigella sativa: A miracle herb. Asian Pacific journal of tropical biomedicine. 2013;3:337–52. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60075-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Majed AA, Al-Omar FA, Nagi MN. Neuroprotective effects of thymoquinone against transient forebrain ischemia in the rat hippocampus. European journal of pharmacology. 2006;543:40–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali BH, Blunden G. Pharmacological and toxicological properties of Nigella sativa. Phytotherapy research : PTR. 2003;17:299–305. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkharfy KM, Al-Daghri NM, Al-Attas OS, Alokail MS. The protective effect of thymoquinone against sepsis syndrome morbidity and mortality in mice. International immunopharmacology. 2011;11:250–4. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammar el SM, Gameil NM, Shawky NM, Nader MA. Comparative evaluation of anti-inflammatory properties of thymoquinone and curcumin using an asthmatic murine model. International immunopharmacology. 2011;11:2232–6. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basarslan F, Yilmaz N, Ates S, Ozgur T, Tutanc M, Motor VK, et al. Protective effects of thymoquinone on vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Human & experimental toxicology. 2012;31:726–33. doi: 10.1177/0960327111433185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batool S, Nawaz MS, Greig NH, Rehan M, Kamal MA. Molecular interaction study of N1-p-fluorobenzyl-cymserine with TNF-alpha, p38 kinase and JNK kinase. Anti-inflammatory & anti-allergy agents in medicinal chemistry. 2013;12:129–35. doi: 10.2174/1871523011312020004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A. Osteopontin: A Key Link between Immunity, Inflammation and the Central Nervous System. Translational neuroscience. 2012;3:288–93. doi: 10.2478/s13380-012-0028-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt MS, Sultan MT. Nigella sativa: reduces the risk of various maladies. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition. 2010;50:654–65. doi: 10.1080/10408390902768797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dariani S, Baluchnejadmojarad T, Roghani M. Thymoquinone Attenuates Astrogliosis, Neurodegeneration, Mossy Fiber Sprouting, and Oxidative Stress in a Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Journal of molecular neuroscience : MN. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s12031-013-0043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rio P, Irmler M, Arango-Gonzalez B, Favor J, Bobe C, Bartsch U, et al. GDNF-induced osteopontin from Muller glial cells promotes photoreceptor survival in the Pde6brd1 mouse model of retinal degeneration. Glia. 2011;59:821–32. doi: 10.1002/glia.21155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Casartelli A, Herreros E, Minnick DT, Day C, George E, et al. Development of a high throughput in vitro toxicity screen predictive of high acute in vivo toxic potential. Toxicology in vitro : an international journal published in association with BIBRA. 2001;15:579–84. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(01)00064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furusawa J, Funakoshi-Tago M, Mashino T, Tago K, Inoue H, Sonoda Y, et al. Glycyrrhiza inflata-derived chalcones, Licochalcone A, Licochalcone B and Licochalcone D, inhibit phosphorylation of NF-kappaB p65 in LPS signaling pathway. International immunopharmacology. 2009;9:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilhotra N, Dhingra D. Thymoquinone produced antianxiety-like effects in mice through modulation of GABA and NO levels. Pharmacological reports : PR. 2011;63:660–9. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyoneva S, Shapiro L, Lazo C, Garnier-Amblard E, Smith Y, Miller GW, et al. Adenosine A2A receptor antagonism reverses inflammation-induced impairment of microglial process extension in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiology of disease. 2014;67:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa-Ishii S, Takei S, Inaba M, Umegaki H, Chiba Y, Furukawa A, et al. Defects in cytokine-mediated neuroprotective glial responses to excitotoxic hippocampal injury in senescence-accelerated mouse. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2011;25:83–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai S, Kim YI, Goto T, Kang MS, Yoshimura M, Obata A, et al. Inhibitory effect of naringenin chalcone on inflammatory changes in the interaction between adipocytes and macrophages. Life sciences. 2007;81:1272–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinzadeh H, Parvardeh S, Asl MN, Sadeghnia HR, Ziaee T. Effect of thymoquinone and Nigella sativa seeds oil on lipid peroxidation level during global cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat hippocampus. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology. 2007;14:621–7. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idris-Khodja N, Schini-Kerth V. Thymoquinone improves aging-related endothelial dysfunction in the rat mesenteric artery. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s archives of pharmacology. 2012;385:749–58. doi: 10.1007/s00210-012-0749-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan HJ, Lee CC, Shih YL, Hueng DY, Ma HI, Lai JH, et al. Osteopontin regulates human glioma cell invasiveness and tumor growth in mice. Neuro-oncology. 2010;12:58–70. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang T, Savarese T, Low HP, Kim S, Vogel H, Lapointe D, et al. Osteopontin expression in intratumoral astrocytes marks tumor progression in gliomas induced by prenatal exposure to N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea. The American journal of pathology. 2006;168:1676–85. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HW, Kang SY, Park KH, Oh TW, Jung JK, Kim SH, et al. Effect of the semen extract of Thuja orientalis on inflammatory responses in transient focal cerebral ischemia rat model and LPS-stimulated BV-2 microglia. The American journal of Chinese medicine. 2013;41:99–117. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X13500080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkonde YV, Morgan WW, Sigala J, Maffi SK, Condello C, Kuziel W, et al. Chemokines in the MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease: absence of CCL2 and its receptor CCR2 does not protect against striatal neurodegeneration. Brain research. 2007;1128:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Li YX, Dewapriya P, Ryu B, Kim SK. Floridoside suppresses pro-inflammatory responses by blocking MAPK signaling in activated microglia. BMB reports. 2013a;46:398–403. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2013.46.8.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Kim JI, Choi JW, Kim M, Yoon NY, Choi CG, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of hexane fraction from Myagropsis myagroides ethanolic extract in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated BV-2 microglial cells. The Journal of pharmacy and pharmacology. 2013b;65:895–906. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek PM, Dixon CE, Shellington DK, Shin SS, Bayir H, Jackson EK, et al. Screening of biochemical and molecular mechanisms of secondary injury and repair in the brain after experimental blast-induced traumatic brain injury in rats. Journal of neurotrauma. 2013;30:920–37. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu JK, Liu L, Shin JW, Surh YJ. Thymoquinone inhibits phorbol ester-induced activation of NF-kappaB and expression of COX-2, and induces expression of cytoprotective enzymes in mouse skin in vivo. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.07.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa P, Kutil Z, Temml V, Malik J, Kokoska L, Widowitz U, et al. Inhibition of in vitro leukotriene B4 biosynthesis in human neutrophil granulocytes and docking studies of natural quinones. Natural product communications. 2013;8:105–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Guan ZZ, Ravid R. Changes of nuclear factor and inflammatory chemotactic factors in brain of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Zhonghua bing li xue za zhi Chinese journal of pathology. 2011;40:585–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Zhao LX, Cao DL, Gao YJ. Spinal injection of docosahexaenoic acid attenuates carrageenan-induced inflammatory pain through inhibition of microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in the spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2013;241:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manivannan J, Tay SS, Ling EA, Dheen ST. Dihydropyrimidinase-like 3 regulates the inflammatory response of activated microglia. Neuroscience. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour MA, Nagi MN, El-Khatib AS, Al-Bekairi AM. Effects of thymoquinone on antioxidant enzyme activities, lipid peroxidation and DT-diaphorase in different tissues of mice: a possible mechanism of action. Cell biochemistry and function. 2002;20:143–51. doi: 10.1002/cbf.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matusan-Ilijas K, Behrem S, Jonjic N, Zarkovic K, Lucin K. Osteopontin expression correlates with angiogenesis and survival in malignant astrocytoma. Pathology oncology research : POR. 2008;14:293–8. doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer AM, Clifford JA, Aldulescu M, Frenkel JA, Holland MA, Hall ML, et al. Cyanobacterial Microcystis aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide elicits release of superoxide anion, thromboxane B(2), cytokines, chemokines, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 by rat microglia. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2011;121:63–72. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed A, Afridi DM, Garani O, Tucci M. Thymoquinone inhibits the activation of NF-kappaB in the brain and spinal cord of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Biomedical sciences instrumentation. 2005;41:388–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed A, Shoker A, Bendjelloul F, Mare A, Alzrigh M, Benghuzzi H, et al. Improvement of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) by thymoquinone; an oxidative stress inhibitor. Biomedical sciences instrumentation. 2003;39:440–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- More SV, Park JY, Kim BW, Kumar H, Lim HW, Kang SM, et al. Anti-neuroinflammatory activity of a novel cannabinoid derivative by inhibiting the NF-kappaB signaling pathway in lipopolysaccharide-induced BV-2 microglial cells. Journal of pharmacological sciences. 2013;121:119–30. doi: 10.1254/jphs.12170fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nili-Ahmadabadi A, Tavakoli F, Hasanzadeh G, Rahimi H, Sabzevari O. Protective effect of pretreatment with thymoquinone against Aflatoxin B(1) induced liver toxicity in mice. Daru : journal of Faculty of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. 2011;19:282–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura T, Katayama T, Obinata C, Iso Y, Chiba Y, Kobayashi H, et al. Neuronal injury induces microglial production of macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha in rat corticostriatal slice cultures. Journal of neuroscience research. 2012;90:2127–33. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padhye S, Banerjee S, Ahmad A, Mohammad R, Sarkar FH. From here to eternity - the secret of Pharaohs: Therapeutic potential of black cumin seeds and beyond. Cancer therapy. 2008;6:495–510. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Kim YH, Kim Y, Lee SJ. Aromatic-turmerone’s anti-inflammatory effects in microglial cells are mediated by protein kinase A and heme oxygenase-1 signaling. Neurochemistry international. 2012;61:767–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passos GF, Figueiredo CP, Prediger RD, Pandolfo P, Duarte FS, Medeiros R, et al. Role of the macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha/CC chemokine receptor 5 signaling pathway in the neuroinflammatory response and cognitive deficits induced by beta-amyloid peptide. The American journal of pathology. 2009;175:1586–97. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radad K, Hassanein K, Al-Shraim M, Moldzio R, Rausch WD. Thymoquinone ameliorates lead-induced brain damage in Sprague Dawley rats. Experimental and toxicologic pathology : official journal of the Gesellschaft fur Toxikologische Pathologie. 2014;66:13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey CP, Tansey MG. A survey from 2012 of evidence for the role of neuroinflammation in neurotoxin animal models of Parkinson’s disease and potential molecular targets. Experimental neurology. 2014;256:126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JK, Sharkey J, Andrews PJ. The temporal expression, cellular localization, and inhibition of the chemokines MIP-2 and MCP-1 after traumatic brain injury in the rat. Journal of neurotrauma. 2009;26:507–25. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo F, Riboldi G, Salani S, Nizzardo M, Simone C, Corti S, et al. Cellular therapy to target neuroinflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2014;71:999–1015. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1480-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo I, Bubacco L, Greggio E. LRRK2 and neuroinflammation: partners in crime in Parkinson’s disease? Journal of neuroinflammation. 2014;11:52. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacino AN, Brooks M, McKinney AB, Thomas MA, Shaw G, Golde TE, et al. Brain injection of alpha-synuclein induces multiple proteinopathies, gliosis, and a neuronal injury marker. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2014;34:12368–78. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2102-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem ML. Immunomodulatory and therapeutic properties of the Nigella sativa L. seed. International immunopharmacology. 2005;5:1749–70. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaranarayanan C, Pari L. Thymoquinone ameliorates chemical induced oxidative stress and beta-cell damage in experimental hyperglycemic rats. Chemico-biological interactions. 2011;190:148–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabana A, El-Menyar A, Asim M, Al-Azzeh H, Al Thani H. Cardiovascular benefits of black cumin (Nigella sativa) Cardiovascular toxicology. 2013;13:9–21. doi: 10.1007/s12012-012-9181-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivers KY, Nikolopoulou A, Machlovi SI, Vallabhajosula S, Figueiredo-Pereira ME. PACAP27 prevents Parkinson-like neuronal loss and motor deficits but not microglia activation induced by prostaglandin J2. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014;1842:1707–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliman ML, Ohm JE, Rosenberger TA. Acetate reduces PGE2 release and modulates phospholipase and cyclooxygenase levels in neuroglia stimulated with lipopolysaccharide. Lipids. 2013;48:651–62. doi: 10.1007/s11745-013-3799-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambuyzer BR, Casteleyn C, Vergauwen H, Van Cruchten S, Van Ginneken C. Osteopontin alters the functional profile of porcine microglia in vitro. Cell biology international. 2012;36:1233–8. doi: 10.1042/CBI20120172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekeoglu I, Dogan A, Ediz L, Budancamanak M, Demirel A. Effects of thymoquinone (volatile oil of black cumin) on rheumatoid arthritis in rat models. Phytotherapy research : PTR. 2007;21:895–7. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesarova H, Svobodova B, Kokoska L, Marsik P, Pribylova M, Landa P, et al. Determination of oxygen radical absorbance capacity of black cumin (Nigella sativa) seed quinone compounds. Natural product communications. 2011;6:213–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah I, Ullah N, Naseer MI, Lee HY, Kim MO. Neuroprotection with metformin and thymoquinone against ethanol-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration in prenatal rat cortical neurons. BMC neuroscience. 2012;13:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-13-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umar S, Zargan J, Umar K, Ahmad S, Katiyar CK, Khan HA. Modulation of the oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokine response by thymoquinone in the collagen induced arthritis in Wistar rats. Chemico-biological interactions. 2012;197:40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzawa A, Mori M, Arai K, Sato Y, Hayakawa S, Masuda S, et al. Cytokine and chemokine profiles in neuromyelitis optica: significance of interleukin-6. Mult Scler. 2010;16:1443–52. doi: 10.1177/1352458510379247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins R, Tucci M, Benghuzzi H. Role of plant-derived antioxidants on NF-kb expression in LPS-stimulated macrophages - biomed 2011. Biomedical sciences instrumentation. 2011;47:222–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong WT. Microglial aging in the healthy CNS: phenotypes, drivers, and rejuvenation. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience. 2013;7:22. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo CC, Kumar AP, Sethi G, Tan KH. Thymoquinone: potential cure for inflammatory disorders and cancer. Biochemical pharmacology. 2012;83:443–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan NT, Shumilina E, Qadri SM, Gotz F, Lang F. Effect of thymoquinone on mouse dendritic cells. Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology. 2010;25:307–14. doi: 10.1159/000276563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y, Shao Z, Sharif S, Du XY, Myles T, Merchant M, et al. Thrombin-cleaved fragments of osteopontin are overexpressed in malignant glial tumors and provide a molecular niche with survival advantage. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:3097–111. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.362954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Bhandaru M, Pasham V, Bobbala D, Zelenak C, Jilani K, et al. Effect of thymoquinone on cytosolic pH and Na+/H+ exchanger activity in mouse dendritic cells. Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology. 2012;29:21–30. doi: 10.1159/000337583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, Liu Z, Wei J, Lu L, Huang Y, Luo L, et al. Protective effect of SIRT1 on toxicity of microglial-derived factors induced by LPS to PC12 cells via the p53-caspase-3-dependent apoptotic pathway. Neuroscience letters. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh CH, Yang ML, Lee CY, Yang CP, Li YC, Chen CJ, et al. Wogonin attenuates endotoxin-induced prostaglandin E2 and nitric oxide production via Src-ERK1/2-NFkappaB pathway in BV-2 microglial cells. Environmental toxicology. 2013 doi: 10.1002/tox.21847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]