Abstract

An economic crisis has been defined as a situation in which the scale of a country's economy becomes smaller in a period of time. Economic crises happen for various reasons, including economic sanctions. Economic crises in a country may affect national priorities for investment and expenditure and reduce available resources, and hence may affect the health care sector including access to medicines. We reviewed the pharmaceutical policies that the countries adopted in order to mitigate the potential negative effects on access to medicines. We reviewed published reports and articles after conducting a comprehensive search of the PubMed and the Google Scholar. After extracting relevant data from the identified articles, we used the World Health Organization (WHO) access to medicines framework as a guide for the categorization of the policies. We identified a total of 40 studies, of which 10 reported the national pharmaceutical policies adopted to reduce the negative impacts of economic crises on access to medicines in high-income and middle-income countries. We identified 89 policies adopted in the 11 countries and categorized them into 12 distinct policy directions. Most of the policies focused on financial aspects of the pharmaceutical sector. In some cases, countries adopted policies that potentially had negative effects on access to medicines. Only Italy had adopted policies encompassing all four accesses to medicine factors recommended by the WHO. While the countries have adopted many seemingly effective policies, little evidence exists on the effectiveness of these policies to improve access to medicines at a time of an economic crisis.

Keywords: Access to medicine, economic or financial crisis, economic sanction, pharmaceutical policy

INTRODUCTION

The economic crisis has been defined as a situation in which the economy scale of a country becomes smaller. In other words, the size of a country's economic activities such as investment level, national earning, capital circulation, and employment is reduced to the extent that eventually may lead to decreasing credits and negative economic growth in the country.[1] Economic crises may happen for various reasons, such as unexpected decline in the value of important assets (e.g., the housing sector), stock market crash, banking crisis, currency devaluation, devaluation of major sources of national income (e.g., raw product exports) and inability to pay heavy debts, and in certain cases it can be inflicted upon a country by economic sanctions. Most of these factors do not occur in isolation from each other, and the presence of one of these factors may result in others to follow. For example, an economic crash in the housing market may result in a credit crisis, which may be followed by a major reduction in household consumption and production levels. Similarly, an economic sanction can trigger most of the above factors.

Economic crises in a country inevitably may affect the priorities of the country for investment and expenditure. The affected countries may need to implement certain strategies to shorten the crisis period and expedite the economic recovery. The countries may also redirect financial resources from certain public responsibilities, such as healthcare or education, to more “pressing needs.” As such, given that within a crisis both the government's and the households’ ability to provide and pay for health care will be affected, a crisis may potentially damage the household's access to required health care and medicines, and increase the frequency of observed drug shortages.[2] In summary, while access to medicines has been one of the most important concerns at national and international levels, and remains a top priority for the World Health Organization (WHO) and other international organizations with similar mandates,[3,4,5,6] economic crises may prevent countries from achieving their desired health care goals, including households’ access to required medicines.

Nonetheless as a result of any concerns over the reduction in access to medicines in a country, policymaker seeking intervention to alleviate the concerns and improve access to medicines.[7] Several European countries were affected by a major economic crisis that started in 2008.[8] Furthermore, several countries around the world have faced economic sanctions that have had negative effects on their economy.[9,10,11,12] In the case of Iran, during 2010–2014 the country faced a major escalation of economic sanctions targeting the country.[9] Several reports documented the challenges these countries faced in the provision of adequate access to medicines and the policy reactions they adopted in response to the economic crises.[13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]

The purpose of this study is to review the pharmaceutical policies and strategies adopted by countries to deal with economic crises and sanctions in order to ensure access to medicines.

METHODS

This article is a policy review based on published reports and articles to assess the policies that different countries have adopted during economic crises and sanctions to diminish the negative effects on access to medicines.

Data sources

We conducted a comprehensive search of the PubMed and complemented the search in the Google scholar to retrieve potentially relevant policy documents published up to February 2015. The following keywords were used: Economic or financial crisis (es), economic sanction(s), medicine or pharmaceutical policy (ies), and access to medicine(s). We considered all studies reporting the relevant policy development, adoption or implementation without imposing any limitations related to study designs. In order not to miss the documents relevant to previous occurrences of economic crises, no time limit was imposed on the identified reports or articles. In addition, we specifically searched for documents about Iran pharmaceutical policies adopted in response to the recent economic sanctions.

Data extraction and synthesis

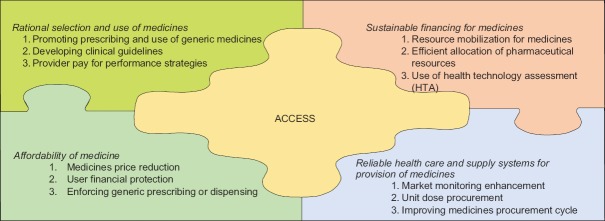

We used the WHO framework for access to medicines as a guide for the identification and categorization of the identified policies. The framework includes four factors that influence access to medicines in a country: Rational selection and use of medicines, affordability of medicines, sustainable financing for medicines, and a reliable health care and supply systems for provision of medicines.[23,24] We extracted the following information from each identified document: The document title, publication year and authors, the affected country name(s), the policy titles, and a description of the elements and objectives of the adopted policies.

We used a qualitative synthesis approach for data analysis, in which the authors discussed and put together the policies that had similar characteristics and policy goals. Then, we categorized the synthesized policies within the WHO access to medicines framework of four factors.

RESULTS

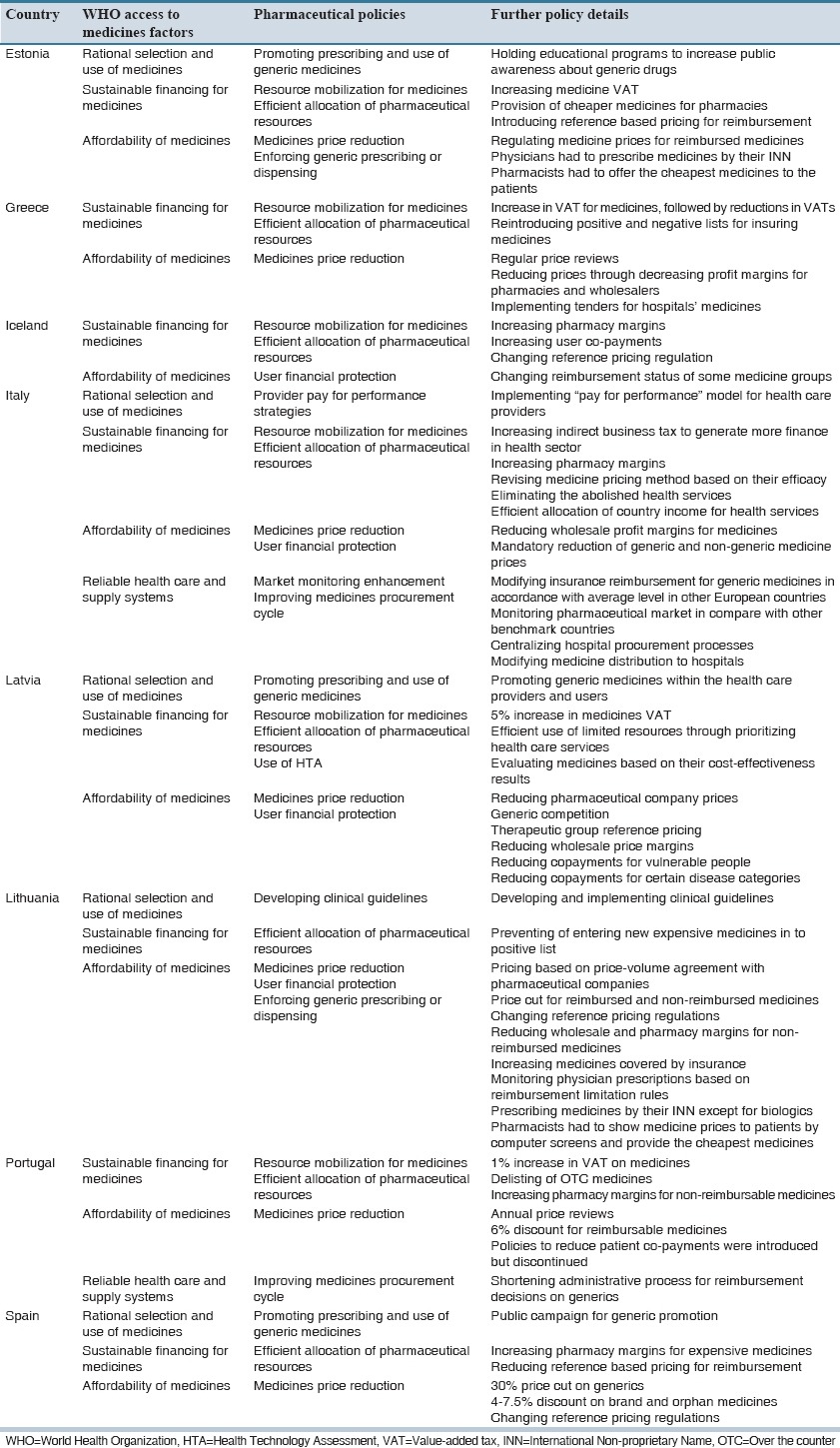

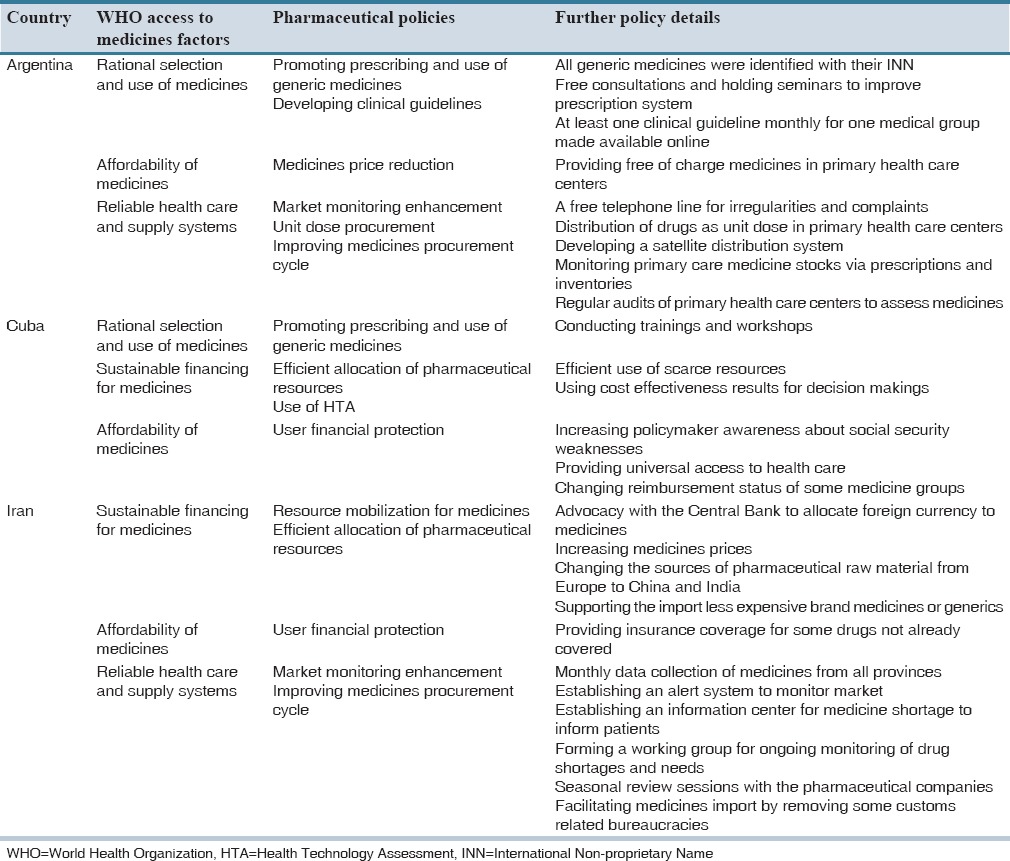

We identified a total of 40 studies (11 reports and 29 articles) that 10 of them reported the development, adoption or implementation of national pharmaceutical policies to reduce the negative impacts of economic crises on access to medicines in eleven countries: Argentina,[15] Cuba,[18,19] Estonia,[17] Greece,[21] Iran,[13] Italy,[14] Latvia,[16] Lithuania[20] and a cross-country assessment of European countries.[22] Table 1 presents the policies identified in eight high-income countries, and Table 2 presents findings related to three middle-income countries. There are no published documents about pharmaceutical policies that were adopted against the economic crisis in lower middle-income or low-income countries.

Table 1.

List of pharmaceutical policies adopted by high income countries

Table 2.

List of pharmaceutical policies adopted by middle income countries

We identified 89 policies adopted by the countries to mitigate the negative effects of economic crises on access to medicines and categorized them into 12 distinguished policy directions. These 12 policy directions were further categorized based on the WHO defined four factors that influence access to medicines [Figure 1].[23,24]

Figure 1.

Policies’ categorization based on World Health Organization access to medicine framework

More detail explanations of each policy with their objectives and actions done by studied countries are described below:

Rational selection and use of medicines

Promoting prescribing and use of generic medicines

One-way of ensuring access to appropriate medicine at the right time is through the promotion of rational use of medicines. Countries use different methods in this area such as holding workshops to increase the public awareness about the fact that generics and brand medicines were the same with the only differences in their prices, encouraging generic prescribing and dispensing for example via conducting training activities for physicians and pharmacists as the main providers of health services.[15,16,17,18,19,22]

Developing clinical guidelines

One important way to assure the rational use of medicines is developing and using clinical guidelines along with effective implementation strategies that help physicians to prescribe the appropriate medicines for the right patients based on health care priorities.[15,16,17,18,19,20]

Provider pay for performance strategies

One method to control medicine's expenditures is preventing the induced demand for less-effective or expensive medicines by using “pay for performance” models that support prescribing of more cost-effective medicines. This method in addition to cost saving has resulted in promoting rational use of medicines.[14]

Sustainable financing for medicines

Resource mobilization for medicines

A number of countries have adopted some policies to enhance access to medicines by allocation of financial resources to medicines such as prioritizing public resources for the importation of medicines and their raw materials over other imported goods, public share of health expenditure (including medicines), diverting public resources from other sectors to health care and medicines, or generating new ear-marked financing routes for medicines.[13,14,16,17,21,22]

Efficient allocation of pharmaceutical resources

This policy targeted pharmaceutical resource allocation through encouragement and support of using domestically produced medicines over imported medicines, import of generic instead of brand medicines, and developing positive lists for medicine reimbursement through insurance coverage or other financing modes. Other countries tried to change their sources of raw material to new producers (of acceptable quality) that offered lower prices to reduce the costs of medicines.[13,14,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]

Use of health technology assessment

Optimal allocation of resources in response to economic crisis is very important for governments and one of the efficient methods in this condition is health technology assessment tool, through which policymakers could be ensured that health resources are being utilized in the best possible way. Therefore, approaches such as using results of economic evaluation for the inclusion of drugs in the country's pharmaceutical list was one of the pharmaceutical policies implemented by some countries during economic crises.[16,18,19]

Affordability of medicines

Medicines price reduction

This policy has been implemented with the purpose of enhancing people's ability to buy medicines. This approach is based on reducing price of medicines through modifying price of particular medicines, mandatory reduction in price of generic medicines, reducing profit margins of medicines or pharmacies and wholesalers, reforming pricing strategies for generics or other medicines by prudent use of reference pricing, offering tenders for hospital medicines, and negotiating with pharmaceutical companies to reduce the price of medicines.[14,15,16,17,20,22]

User financial protection

The other approach to increase drug affordability is user protection against the financial implications of the use of medicines. Usually, two main approaches are followed to achieve this aim. First, reforming insurance reimbursement system by increasing reimbursement for generics, and enhancing insurance coverage through reduced or abolished co-payments; and second, building targeted social safety nets (via health insurance or otherwise) that enhance access to medicines for socioeconomically disadvantaged groups or those affected with expensive to treat diseases.[13,14,16,18,19,20,22]

Enforcing generic prescribing or dispensing

The policy involved obligatory measures (as compared with promotional interventions) to ensure physicians prescribe medicines by their International Nonproprietary Names, pharmacies substitute generics, compulsory availability of cheapest generic medicines, and clear display of medicines prices to patients.[17,20]

Ensuring a reliable health care and supply systems for provision of medicines

Market monitoring enhancement

This policy has been implemented in different countries by various methods in order to identify more rapidly and accurately the market needs and medicine shortages in the country. The approaches include monthly collections of medicine consumption or distribution data, establishing an immediate warning system to detect the shortages, expanding the data collection network to all parts of the country, establishing an information center for medicine shortages (e.g., a hotline or webpage), developing working groups to review the country's drug list appropriate to market needs, increasing interactions with the pharmaceutical manufacturers and importers, for example via formal meetings or forums, and executing programs to receive customers’ complaints about medicine availability.[13,14,15]

Unit dose procurement

Unit dose procurement is a pharmaceutical administration approach in which medicines are packaged in single unit packages for individual use per day. This administration approach can be used as policy with the main goal of reducing or preventing medicines’ waste at the administration level and diminishing the administration errors. Some countries adopted this policy for hospitals, primary health care centers or community pharmacies to improve their pharmaceutical supply chain.[15]

Improving medicines procurement cycle

This policy has been applied to reform the supply chain through various approaches. Some examples include changing medicine supply and distribution system, especially in the area of hospital medicines, or facilitating medicines import route through removing some administrative or customs bureaucracies.[13,14,15,22]

DISCUSSION

We identified 89 policies adopted by the countries that were in line with the main objective of ensuring access to medicines. The policy directions most frequently adopted by both high and upper middle-income countries were efficient allocation of pharmaceutical resources (10 countries), medicines price reductions (eight countries), and user financial protection (six countries). Upper middle-income countries focused more on increasing affordability of medicines through medicine price reduction and user financial protection policies.

Only one country (Italy) had adopted policies encompassing all four factors influencing access to medicine based on the WHO framework.

Among these countries, two of them were affected by economic crises as a result of economic sanctions. While many more countries had faced economic crises within the last few decades (including at least 15 countries inflicted by economic sanctions)[25] few published reports existed to include in this study.

Our study also revealed adoption of certain policies that might have resulted in a reduced access to medicines rather than improving it, for example increased pharmacy margins (e.g., Iceland, Italy), increase in medicine prices via increase in medicines’ value-added tax or medicines prices (e.g., Estonia, Greece, Iran, Latvia, Portugal), and increase in user co-payments (e.g., Iceland).[13,14,16,17,21,22] Such policies had been apparently adopted to increase the financial viability of the pharmaceutical sector or the health sector through the crisis period, still were not in line with the main policy objective of improving access to medicines in the countries. As a result some countries (e.g., Greece) had reversed the policies that increased the costs of the medicines. It seems that medicines’ price increases might have happened more widely in several countries for reasons not related to the economic situation of the countries affected by the economic crises.[26]

Among studies conducted about economic crises and their effects on the health sector, there are few cases that assessed the pharmaceutical policies adopted by inflicted countries. A recent survey of European countries assessed the policies implemented in the pharmaceutical sector of these countries after the financial crisis.[22] While we have included the findings of the survey in our results, our study adds some advantages. First our study is not limited to European countries and includes countries affected by a financial crisis for any reason that has occurred anywhere around the world. Second, we used the WHO access to medicines framework to categorize the policies. And finally we included all the related policies while Vogler et al. study mainly focused on policies dealing with the pricing and financing aspects of the pharmaceutical sector.[22] Furthermore, there are reports about economic crises and their effects on health status and pharmaceutical sector conducted by international organizations such as the OECD, the World Bank, and the WHO. In general, these reports explain the global situation and do not evaluate the policies adopted against economic crises in detail.[26,27,28]

The observable focus on financial aspects of the pharmaceutical sector during the economic crises shows that such policies, at least in the view of national policy makers, are part of a prudent response to mitigate the negative effects of the crises. The publication of reports explaining financial policies in the pharmaceutical sector is a welcome shift in the literature as previous reviews had documented the scarcities of such studies.[23] Still we had anticipated to see a more diverse set of policies, and, in particular, a further focus on the demand side aspects of access to medicines. It is important to note it might also be possible to decrease pharmaceutical expenditure without decreasing the availability of pharmaceuticals or appropriate access to medicine by the more vigorous promotion of generics and rational prescribing and use of medicines.[15,20] Policies taken in order to prioritize health services based on their effectiveness (e.g., development and implementation of evidence-based clinical guidelines) may help substitution of less-effective or more costly medicines with cost-effective options.[29] However, it should be noted that such policies are more time-consuming to implement than policies focused on price or financial aspects of the pharmaceutical market, and as such may not be applicable within a short-term period of an on-going economic crisis.

Countries have also used the economic crises to implement system-wide reforms in the health system that may also enhance equitable access to medicines. Argentina, Cuba, and Latvia concentrated on enhancing primary health care, providing free essential medicines, and improving their social safety nets in order to diminish the negative effects of the economic crises on access to medicines.[15,16,18,19]

Still a major limitation of our study, and the included studies, is that the available evidence does not provide reliable evidence of effect (or a lack of effect) of the adopted policies, although some studies claimed that countries such as Lithuania had achieved their goals.[20] Future studies should focus on the primary evaluation of the policies’ impact using research designs such as interrupted times series.[30] Another important limitation is that we only included papers published in English language, although we did not face any relevant one published in other languages.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors contributed the idea of research, design of study, data analysis and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Financial support and sponsorship Nil.

Conflict of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alcorta L, Nixson F. The Global Financial Crisis and the Developing World: Impact on and Implications for the Manufacturing Sector. Vienna: United Nations Industrial Development Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Protocol for the notification and communication of drug shortages. Quebec: 2013. The Multi-stakeholder Steering Committee on Drug Shortages. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Methodology Report 2012 Stakeholder Review: Access to Medicine Foundation. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Trade, Foreign Policy, Diplomacy, Health. [Last accessed on 2015 Apr 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/trade/glossary/story002/en/

- 5.The Changing Landscape on Access to Medicines. Geneva: IFPMA; 2012. International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations. [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO and UNICEF. Meeting Report: Essential Medicines for Children Expert Consultation 4. Geneva: 2006. Sep, [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis M, Verhoeven M. Financial Crises and Social Spending, the Impact of the 2008–2009 Crisis. Washington: World Bank; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karanikolos M, Mladovsky P, Cylus J, Thomson S, Basu S, Stuckler D, et al. Financial crisis, austerity, and health in Europe. Lancet. 2013;381:1323–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheraghali AM. Impacts of international sanctions on Iranian pharmaceutical market. Daru. 2013;21:64. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-21-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noland M. The (Non) Impact of UN Sanctions on North Korea. Washington: Peterson Institute for International Economics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrow D, Carrie M. The economic impacts of the 1998 sanctions on India and Pakistan. Nonproliferation Rev. 1999 Fall;:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garfield R. Relief and Rehabilitation Network. London: Overseas Development Institute; 1999. The Impact of Economic Sanctions on Health and Well-being. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosseini SA. Impact of sanctions on procurement of medicine and medical devices in Iran; a technical response. Arch Iran Med. 2013;16:736–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Belvis AG, Ferrè F, Specchia ML, Valerio L, Fattore G, Ricciardi W. The financial crisis in Italy: Implications for the healthcare sector. Health Policy. 2012;106:10–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Homedes N, Ugalde A. Improving access to pharmaceuticals in Brazil and Argentina. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21:123–31. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czj011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Behmane D, Innus J. Pharmaceutical policy and the effects of the economic crisis: Latvia. Eurohealth. 2011;4:69–79. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rüütel D, Pudersell K. Pharmaceutical policy and the effects of the economic crisis: Estonia. Eurohealth. 2011;17:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van der Stuyft P, De Vos P, Hilderbrand K. USA and shortage of food and medicine in Cuba. Lancet. 1997;349:363. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)62872-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garfield R. USA and shortage of food and medicine in Cuba. Lancet. 1997;349:363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)62871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garuoliene K, Alonderis T, Marcinkevicius M. Eurohealth: Pharmaceutical policy and the effects of the economic crisis: Lithuania. Eurohealth. 2011;17:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vandoros S, Stargardt T. Reforms in the Greek pharmaceutical market during the financial crisis. Health Policy. 2013;109:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogler S, Zimmermann N, Leopold C, de Joncheere K. Pharmaceutical policies in European countries in response to the global financial crisis. South Med Rev. 2011;4:69–79. doi: 10.5655/smr.v4i2.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rashidian A, Jahanmehr N, Jabbour S, Zaidi S, Soleymani F, Bigdeli M. Bibliographic review of research publications on access to and use of medicines in low-income and middle-income countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: Identifying the research gaps. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003332. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO. Equitable Access to Essential Medicines: A Framework for Collective Action. Geneva: WHO Policy Perspectives on Medicines; 2004. No. 008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Business and Sanctions Consultations. Netherlands. Sanctions List Countries. [Last accessed on 2015 Apr 15]. Available from: http://www.bscn.nl/sanctions-consulting/sanctions-list-countries .

- 26.Buysse IM, Laing RO, Mantel AK. Impact of the economic recession on the pharmaceutical sector. Utrecht: Universities Utrecht; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Gool K, Pearson M. Health, Austerity and Economic Crisis: Assessing the Short-term Impact in OECD Countries. OECD Health Working Papers; 2014. No. 76. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider P. Europe and Central Asia Knowledge Brief. Vol. 8. Washington DC: The World Bank; 2009. Mitigating the impact of the economic crisis on public sector health spending. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rashidian A. Adapting valid clinical guidelines for use in primary care in low and middle income countries. Prim Care Respir J. 2008;17:136–7. doi: 10.3132/pcrj.2008.00055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rashidian A, Joudaki H, Khodayari-Moez E, Omranikhoo H, Geraili B, Arab M. The impact of rural health system reform on hospitalization rates in the Islamic Republic of Iran: An interrupted time series. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;1(91):942–9. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.111708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]