Abstract

Testicular cancer represents 1% to 1.5% of neoplasias in males and 5% of urologic tumors in general. The incidence of bilateral testicular tumors is 1–5%. Approximately one third of the cases are diagnosed as synchronous, while the other two thirds are diagnosed as metachronous tumors. Additionally, 5% of all patients diagnosed with testicular cancer may have contralateral intratubular germ cell neoplasia and may develop a contralateral germ cell tumor. However, few data are available regarding bilateral testicular germ cell tumors (BTGCTs). In this review, we aim to provide an overview of the incidence, pathological features and clinical outcomes.of BTGCTs.

Keywords: Bilateral testicular cancer, bilateral testicular germ cell tumor, testicular germ cell tumor

Though testicular cancers are rarely seen malignancies among male neoplasms, they are the most frequently encountered malignancies in men aged 20–40 years. Nonseminomatous tumors, and pure seminomas are most frequently seen in the third, and fourth decade of life, respectively. Besides, in developed countries, it has a rapidly increasing incidence within the last 30 years.[1] In the Western world, every year 3–6 new cases are seen among 100,000 men.[2] In Scandinavian countries testicular tumors are more frequently seen than Asian countries, and differ according to ethnicity, and socioeconomic level of the patients.

Recognized risk factors in the development of testicular tumors include past or current history of cryptorchidism or undescended testis, Klinefelter syndrome, testicular cancer in the first degree relatives, presence of tumor or intraepithelial neoplasia in the contralateral testis, and infertility.[3–5] In a relevant study, cryptorchidism was detected in 9.5% the patients with bilateral, and in 2.2% of unilateral germ cell tumors.[3] In a study performed in M.D. Anderson Cancer Center on bilateral testis tumors, the investigators couldn’t reveal any history of cryptorchidism in any of their study population.[6] Patel et al.[7] published outcomes of a study on synchronous, and metachronous bilateral testicular tumors performed by Mayo Clinic, and detected past history of cryptorchidism in 10.5% of 19 patients (one patient with bilateral, and one with unilateral cryptorchidism). Besides, atrophic testis was associated with the development of testicular tumor.[8]

Pathological features, and incidence rates of BGCTs

Germ cell tumors constitute 90–95% of testicular tumors. Seminomas, and nonseminomatous tumors constitute 40, and 60% of these tumors. Bilateral testicular tumors generally have the same histological structure. Seminomas are the most frequently (48%) seen histological type, followed by nonseminomatous (15%), and nongerminal (22%) tumors.[9] In men over 50 years of age, most often testicular lymphomas are seen. They are bilateral in 35% of the cases with frequently bilateral involvement.[10]

The incidence of bilateral testicular tumor ranges between 1, and 5 percent.[11–14] One of the first investigations on bilateral testicular germ cell tumors (BGCT) was performed in the year 1941 by Gilbert, and Hamilton on 1466 patients with primary testicular tumors. They detected bilateral testicular tumors in 1.6% of the patients.[15] Aristizabal et al.[16] analyzed 4864 patients with testicular tumors in the year 1978, and detected bilateral tumors in 1.56% of their patients. Incidence of bilateral tumors was reported as 1.2% by Johnson et al.[17] in 1974, and 5.8% by Cockburn et al.[18] in 1983. In the year 1990, Patel et al.[7] detected bilateral testicular tumors in 500 patients with testicular tumors. Che et al.[6] 2431 detected bilateral testicular germ cell tumors in 1% of the patients with testicular germ cell tumors. In our cocuntry, Akdoğan et al.[19] investigated 987 patients, and detected bilateral testicular tumors in 3% of these patients.

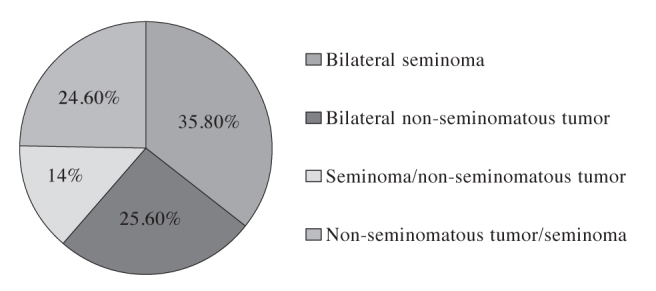

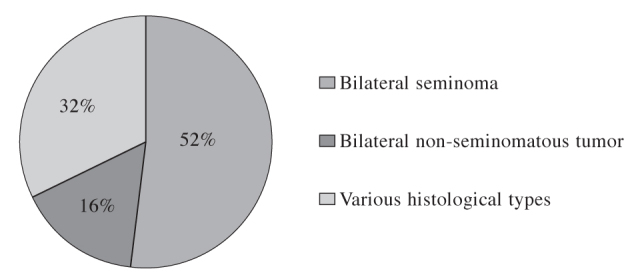

Bilateral testicular tumors are either synchronous (simultaneous) or metachronous (developed at different time points). Synchronous tumors become apparent at the time of diagnosis or within the first two months after establishment of the diagnosis. The incidence of synchronous tumors is 1–2.8%, while of metachronous tumors it is 2.4–5.2 percent.[9] Hentrich et al.[20] followed up 1180 patients with testicular germ cell tumors, and detected synchronous, and metachronous testicular tumors in 1.1 (n=14), and 2.7% (n=33) of the patients, respectively. Fifty-eight (1.5%) bilateral testicular tumors (synchronous 17%, and metachronous, 83%) were detected in a large-scale study on 3984 patients with testicular tumors in a survey performed by Holzbeierlein et al.[21] from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer. From the perspective of tumor histology, synchronous or metachronous types demonstrate differences (Figures 1, 2). Finally, in a systematic study published in 2012 where 50.376 patients were screened, incidence of bilateral testicular tumors was 1.82% including metachronous (1.26%), and synchronous (0.56%) cases.[22]

Figure 1.

Histological characteristics of metachronous BTGCTs

BTGCT: bilateral testicular germ cell tumors

Figure 2.

Histological characteristics of synchronous BTGCTs

BTGCT: bilateral testicular germ cell tumors

The terms testicular intraepithelial neoplasia (TIN), carcinoma in situ (CIS), intratesticular germ cell neoplasia (ITGCN) define the same histology. TIN is the precursor lesion of spermatocytic seminoma in the elderly, and yolk sac tumors in infants, and testicular germ cell tumors excluding mature teratoma. TIN is confined within seminifer tubuli, and therefore it is noninvasive. It was originally defined by Skakkebaek in 2 patients who were biopsied with the indication of infertility.[23]

The incidence of TIN in general population ranges between 1 and 5%, and various factors are effecting its incidence.[24,25] The reported incidence rates of TIN are as follows: cryptorchidism, 2–4%; infertility, 2.2%, and contralateral testicular tumor, 5%.[26–28]

Different biopsy criteria for the investigation of the presence of TIN which is the precursor lesion of testicular germ cell tumors have been suggested in the literature. In some European centers contralateral testicular biopsies were obtained because of detection of concomitant TIN in 4–6% of the cases. Von der Maase et al.[29] indicated risk of invasive growth of TIN as 40, and 50% within the first 3, and 5 years after establishment of diagnosis, respectively. However, in the USA, testicular biopsies are not routinely performed. Herr et al.[30] did not recommend routine contralateral testis biopsy in that it has a lower rates of positivity, and also induces emotional stress in patients. A consensus has been built in the literature concerning its use in high-risk patients, and those with a history of infertility, cryptorchidism, and atrophic testis.[31] European Germ Cell Cancer Consensus Group (EGCCCG) defined patients with smaller testicular volume (<12 mL), history of cryptorchidism or those younger than 30 years of age as high-risk patients for contralateral testicular biopsy.[32] In conclusion, despite lack of consensus concerning testicular biopsy, contralateral testicular biopsy should be included among alternatives which must be discussed with the patient before the final decision.

Clinical features, and treatment

Because of scarcity of bilateral testicular germ cell tumors, most of the publications are in the form of case reports or small-scale studies. This fact restricts the scope of debates on treatment strategies.[23] Bilateral testicular tumors are generally diagnosed at an early stage, and they have a good prognosis. Hentrich et al.[20] performed a study on 1180 patients with testicular tumors, and reported an average disease-free survival of 37 months in 14 patients with bilateral synchronous tumors. In metachronous tumors, after an average of 71 months, the investigators noticed a second tumor, and detected Stage I metachronous tumors in 30 out of 33 patients with metachronous tumors. Similarly Holzbeierlein et al.[21] shared their nearly 50 years of their experiences, and investigated 3984 patients with testicular tumors, and stated that generally low-stage metachronous tumors became apparent an average of 50 months after their first diagnosis. In a review article by Zequi et al.[22], 5-year survival rates were detected to be 88, and 95% for synchronous, and metachronous tumors, respectively. In the same review article, the authors indicated that nearly 50% of synchronous, and 74% of metachronous tumors were Stage 1 tumors. In our country, Akdoğan et al.[19] reported that metachronous tumors had developed after an average of 75 months, most of them being Stage 1 tumors. They also stated that seminomas carry 2-fold higher risk as for development of bilateral testicular tumors. Numerous studies suggested the effective role of platinum-based chemotherapeutics in the decreased incidence of contralateral testicular tumors. Van Basten et al.[33] detected 3-fold lower rates of contralateral tumors in patients receiving chemotherapeutic agents. In a SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program) study conducted by Fossa et al.[34], the authors attributed lower incidence rates of contralateral cancer to the use of platinum-based chemotherapeutic agents.

Current guidelines contain scarce information about bilateral disease.[35] Therapeutic approach of especially infertile patients with bilateral germ cell testicular tumors or solitary testicular cancer is organ preserving surgery. Management of secondary testicular tumors should be achieved in consideration of histology, and stage of the primary tumor which is not different from treatment principles of primary tumor. If adjuvant radiotherapy or retroperitoneal lymph node was applied for a primary tumor, then monitorization or chemotherapy can be implemented based on the stage of the secondary tumor.[20] Recently, organ preserving surgery is in the foreground, and partial orchidectomy which has been revived nowadays as an alternative to partial orchidectomy can be performed in experienced centers. Fundamental foundation of partial orchidectomy rests on the maintenance of physiological androgen production, and fertility. It was firstly performed by Richie in USA in the year 1984.[36] Weissbach[37] described the principles of partial orchidectomy. Partial orchidectomy can be applied in synchronous or metachronous organ-confined testicular tumors smaller than 2 cm localized away from testicular vasculature which involve less than 30% of the testicular volume with negative surgical margins without histopathologically detected TIN in intraoperative biopsy specimens.[38] Because of higher rates of TIN concomitancy (80–90%), the patients should receive postoperative radiotherapy at a dose of 18–20 Gy.[39] Potential development of infertility, and androgen insufficiency secondary to postoperative radiotherapy should be kept in mind, and before initiation of the radiotherapy the patients should be informed about this issue.

Patients with testicular tumors should be monitored for lifelong. In addition to examinations, and analytical tests required from the clinician, patient’s self-examination conveys importance. The patients should also receive appropriate education on this subject. Various studies have demonstrated that self-examination attempts were effective in the detection of smaller secondary tumors at an early stage.

Hormone replacement therapy should be provided to treat potential androgen insufficiency which might develop following bilateral or partial orchidectomy. Among various testosterone formulations, controlled-release transdermal patches which ensure more stable serum testosterone levels should be preferred.[39] Serum testosterone levels of these patients should be regularly monitored.

An important consideration in bilateral testicular tumors which are seen in the second, and fourth decade of life is that patients who wants to be a father should undergo preoperative sperm freezing procedure, and they should be informed about assisted reproductive technologies. Besides, the patients should be provided with detailed information about cosmetically important testicular prostheses.

In conclusion, despite its increasing incidence in recent years, still bilateral testicular tumors have lower incidence rates. Bilateral testicular tumors have generally the same histological structure, and most frequently testicular seminomas are seen. Since TIN is observed in 5% of the cases with contralateral testicular tumor, routine contralateral testicular biopsy is not recommended for the detailed evaluation of TIN in these patients. Partial orchiectomy can be an alternative for eligible patients in experienced centers. Self-examination of the patients is very important. Since these tumors are seen in youngsters, these patients should receive necessary treatments for infertility, and androgen insufficiency. With appropriate treatment modalities, excellent outcomes, and longer survival rates can be achieved in bilateral testicular tumors.

Footnotes

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - H.S.; Design - H.S.; Supervision - M.E.; Funding - H.S.; Materials - O.T.; Data Collection and/or Processing - H.S., O.T.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - M.E.; Literature Review - H.S., O.T.; Writer - H.S.; Critical Review - O.T.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Huyghe E, Matsuda T, Thonneau P. Increasing incidence of testicular cancer worldwide: a review. J Urol. 2003;170:5–11. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000053866.68623.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schottenfeld D, Warshauer ME, Sherlock S, Zauber AG, Leder M, Payne R. The epidemiology of testicular cancer in young adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;112:232–46. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dieckmann KP, Loy V, Buttner P. Prevalence of bilateral testicular germ cell tumours and early detection based on contralateral testicular intra-epithelial neoplasia. Br J Urol. 1993;71:340–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb15955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westergaard T, Olsen JH, Frisch M, Kroman N, Nielsen JW, Melbye M. Cancer risk in fathers and brothers of testicular cancer patients in Denmark. A population-based study. Int J Cancer. 1996;66:627–31. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960529)66:5<627::AID-IJC8>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albers P, Albrecht W, Algaba F, Bokemeyer C, Cohn-Cedermark G, Fizazi K, et al. EAU guidelines on testicular cancer: 2011 update. Eur Urol. 2011;60:304–19. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Che M, Tamboli P, Ro JY, Park DS, Ro JS, Amato RJ, et al. Bilateral testicular germ cell tumors: twenty-year experience at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. Cancer. 2002;95:1228–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel SR, Richardson RL, Kvols L. Synchronous and metachronous bilateral testicular tumors. Mayo Clinic experience. Cancer. 1990;65:1–4. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900101)65:1<1::aid-cncr2820650103>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGlynn KA, Devesa SS, Sigurdson AJ, Brown LM, Tsao L, Tarone RE. Trends in the incidence of testicular germ cell tumors in the United States. Cancer. 2003;97:63–70. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrew JS, Timothy DG. Neoplasms of the Testis Campell-Walsh Urology. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2012. pp. 837–70. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitolo U, Ferreri AJ, Zucca E. Primary testicular lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:183–9. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osterlind A, Berthelsen JG, Abildgaard N, Hansen SO, Hjalgrim H, Johansen B, et al. Risk of bilateral testicular germ cell cancer in Denmark: 1960–1984. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:1391–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.19.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colls BM, Harvey VJ, Skelton L, Thompson PI, Frampton CM. Bilateral germ cell testicular tumors in New Zealand: experience in Auckland and Christchurch 1978–1994. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2061–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.7.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheiber K, Ackermann D, Studer UE. Bilateral testicular germ cell tumors: a report of 20 cases. J Urol. 1987;138:73–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)42995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dieckmann KP, Boeckmann W, Brosig W, Jonas D, Bauer HW. Bilateral testicular germ cell tumors. Report of nine cases and review of the literature. Cancer. 1986;57:1254–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860315)57:6<1254::aid-cncr2820570632>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilbert JB, Hamilton JB. Studies in malignant tumor of the testis. IV. Bilateral testicular cancer. Incidence, nature and bearing open management of the patient with a single testicular cancer. Cancer Res. 1942;21:125–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aristizabal S, Davis JR, Miller RC, Moore MJ, Boone MLM. Bilateral primary germ cell testicular tumors. Report of four cases and review of the literature. Cancer. 1978;42:591–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197808)42:2<591::aid-cncr2820420227>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson DW, Morneau JE. Bilateral sequential germ cell tumors of the testis. Urology. 1974;4:567–70. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(74)90491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cockburn AG, Vugrin D, Batata M, Hajdu S, Whitmore WF. Second primary germ cell tumors in patients with seminoma of the testis. J Urol. 1983;130:357–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)51149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akdoğan B, Divrik RT, Tombul T, Yazıcı S, Tasar Ç, Zorlu F, et al. Bilateral testicular germ cell tumors in Turkey: Increase in incidence in last decade and evaluation of risk factors in 30 patients. J Urol. 2007;178:129–33. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hentrich M, Weber N, Bergsdorf T, Liedl B, Hartenstein R, Gerl A. Management and outcome of bilateral testicular germ cell tumors: Twenty-five year experience in Munich. Acta Oncol. 2005;44:529–36. doi: 10.1080/02841860510029923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holzbeierlein JM, Sogani PC, Sheinfeld J. Histology and clinical outcomes in patients with bilateral germ cell tumors: The Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center experience 1950 to 2001. J Urol. 2003;169:2122–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000067462.24562.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zequi Sde C, da Costa WH, Santana TB, Favaretto RL, Sacomani CA, Guimaraes GC. Bilateral testicular germ cell tumours: a systematic review. BJU Int. 2012;110:1102–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skakkebaek NE. Possible Carsinoma-in-situ of the testis. Lancet. 1972;2:516–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)91909-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dieckmann KP, Skakkebaek NE. CIS of the testis: Review of biological and clinical features. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:815–22. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19991210)83:6<815::aid-ijc21>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sonneveld DJ, Schraffordt Koops S, Sleijfer D, Hoekstra HJ. Bilateral testicular germ cell tumors in patients with initial stage I disease: Prevalence and Prognosis- Asingle centre’s 30 years experience. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1363–7. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moller H, Skakkebaek NE. Risk of testicular cancer in subfertile men: Case-control study. BMJ. 1999;83:815–22. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7183.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dieckmann KP, Pichlmeier U. Clinical epidemiology of testicular germ cell tumors. World J Urol. 2004;22:2–14. doi: 10.1007/s00345-004-0398-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giwercman A, Bruun E, Frimodt-Moller C, Skakkebaek NE. Prevalence of carcinoma in situ and other histopatological abnormalities in testes of men with a history of cryptorchidism. J Urol. 1989;142:998–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38967-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Von der Maase H, Rorth M, Walbom-Jorgensen S, Sorensen B, Christophersen IS, Hald T, et al. Carsinoma in situ of contralateral testis in patients with testicular germ cell cancer: Study of 27 cases in 500 patients. Br Med J (Clin Re Ed) 1986;293:1398–401. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6559.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herr HW, Sheinfeld J. Is biopsy of the contalateral testis necessary in patients with germ cell tumors? J Urol. 1997;158:1331–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee E, Holzbeierlein J. Management of the contralateral testicle in patients with unilateral testicular cancer. World J Urol. 2009;27:421–6. doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0410-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krege S, Beyer J, Souchon R, Albers P, Albrecht W, Algaba F, et al. European consensus conference on diagnosis and treatment of germ cell cancer.: A report of the second meeting of the European Germ Cell Cancer Consensus Group (EGCCCG): Part I. Eur Urol. 2008;53:478–96. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Basten JP, Hoekstra HJ, van Driel MF, Sleijfer DT, Droste JH, Schraffordt Koops H. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy changes the incidence of bilateral testicular cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4:342–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02303585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fossa D, Chen J, Schonfeld SJ, McGlynn KA, McMaster ML, Gail MH, et al. Risk of contralateral testicular cancer: A population-based study of 29,515 U.S. men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1056–66. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parker S, Armitage M. Experience with transdermal testosterone replacement for hypogonadal men. Clin Endoc. 1999;50:57–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1999.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richie JP. Simultaneous bilateral testis tumors with unorthodox management. World J Urol. 1984;2:74. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weissbach L. Organ preserving surgery of malignant germ cell tumors. J Urol. 1995;153:90–3. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199501000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bazzi WM, Raheem OA, Stroup SP, Kane CJ, Derweesh IH, Downs TM. Partial orchiectomy and testis intratubular germ cell neoplasia: World literature review. Urol Ann. 2011;3:115–8. doi: 10.4103/0974-7796.84948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Albers P, Albrecht W, Algaba F, Bokemeyer C, Cohn-Cedermark G, Fizazi K, et al. EAU guidelines on testicular cancer: 2011 update. Eur Urol. 2011;60:304–19. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]