Abstract

Background

Plasmodium vivax infections commonly contain multiple genetically distinct parasite clones. The detection of multiple-clone infections depends on several factors, such as the accuracy of the genotyping method, and the type and number of the molecular markers analysed. Characterizing the multiplicity of infection has broad implications that range from population genetic studies of the parasite to malaria treatment and control. This study compared and evaluated the efficiency of neutral and non-neutral markers that are widely used in studies of molecular epidemiology to detect the multiplicity of P. vivax infection.

Methods

The performance of six markers was evaluated using 11 mixtures of DNA with well-defined proportions of two different parasite genotypes for each marker. These mixtures were generated by mixing cloned PCR products or patient-derived genomic DNA. In addition, 51 samples of natural infections from the Brazil were genotyped for all markers. The PCR-capillary electrophoresis-based method was used to permit direct comparisons among the markers. The criteria for differentiating minor peaks from artifacts were also evaluated.

Results

The analysis of DNA mixtures showed that the tandem repeat MN21 and the polymorphic blocks 2 (msp1B2) and 10 (msp1B10) of merozoite surface protein-1 allowed for the estimation of the expected ratio of both alleles in the majority of preparations. Nevertheless, msp1B2 was not able to detect the majority of multiple-clone infections in field samples; it identified only 6 % of these infections. The merozoite surface protein-3 alpha and microsatellites (PvMS6 and PvMS7) did not accurately estimate the relative clonal proportions in artificial mixtures, but the microsatellites performed well in detecting natural multiple-clone infections. Notably, the use of a less stringent criterion to score rare alleles significantly increased the sensitivity of the detection of multi-clonal infections.

Conclusions

Depending on the type of marker used, a considerable amplification bias was observed, which may have serious implications for the characterization of the complexity of a P. vivax infection. Based on the performance of markers in artificial mixtures of DNA and natural infections, a minimum panel of four genetic markers (PvMS6, PvMS7, MN21, and msp1B10) was defined, and these markers are highly informative regarding the genetic variability of P. vivax populations.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12936-015-0846-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Malaria, Plasmodium vivax, Multiple-clone infection, Molecular markers, Genetic variability, PCR-capillary electrophoresis-based method, Molecular epidemiology

Background

Plasmodium vivax is globally the most widely distributed Plasmodium species that infects humans, being common in tropical and sub-tropical areas outside of Africa [1, 2]. Several factors have highlighted the clinical importance of malaria caused by P. vivax, such as the spread of parasite resistance to available drugs [3]. In addition, the concept of vivax malaria as a benign disease has evolved with the description of severe cases and even deaths [4–6]. Finally, dormant forms of the parasite in the liver, i.e., hypnozoites, act as a reservoir for the disease and have hindered the control of malaria caused by P. vivax [7]. These factors have all increased interest in vivax malaria, primarily in the new Malaria Eradication Research Agenda (malEra) [8].

Plasmodium vivax infections are often characterized by the presence of two or more genetically distinct parasites in the same individual [9–11]. These infections are very common in malaria-endemic areas worldwide [12–11] and can arise from a single mosquito bite carrying a mixture of parasites or from inoculation by different mosquitoes carrying single clones. Additionally, relapses of P. vivax infection due the reactivation of hypnozoites can contribute to increased clonal diversity. As a result, the association between the multiplicity of P. vivax infection and malaria endemicity is weak, with areas of low endemicity sometimes featuring high rates of multiple infections [10–12]. The number of parasite clones in a patient varies greatly, and some infections contain up to nine clones [12]. Characterizing the multiplicity of infection has broad implications ranging from population genetic studies of the parasite to malaria treatment and control. First, evolutionary and population genetic studies rely on accurate parasite genotype/haplotype inference, which is non-trivial when more than one clone is present and clones differ at examined loci [13, 14]. Second, characterizing the within-host diversity is essential to address several issues, such as differentiation between new infection and recrudescence, in order to better estimate the true risk of treatment failure and explore the dynamics of clones influenced by host immunity during anti-malarial treatment or challenge with vaccine [12, 15, 16]. Third, malaria patients infected by multiple parasite strains have been shown to be at a higher risk of treatment failure [17]. Thus, a broad understanding of the genetic diversity of parasite populations can contribute to the definition of control measures, including an appropriate anti-malarial treatment.

The publication of the complete genome sequence of P. vivax has led to the discovery of many molecular markers, such as microsatellites, tandem repeats and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [18]. These markers have proven useful for population genetic studies and for the characterization of the multiplicity of P. vivax infections. However, many studies have shown that the characterization of multi-clonal infections depends on both the accuracy of the genotyping method, and the type and number of the molecular markers analysed [19, 20]. Thus, the use of different approaches may significantly affect the ability to detect multi-clonal P. vivax infections and may hinder comparability among studies [21, 22]. Furthermore, the method used may influence the estimation of the relative abundance of clones in multiple infections.

This study evaluated and compared the ability of different molecular markers—two microsatellites, one tandem repeat and three antigen-coding genes—to estimate the number and the relative abundance of alleles present in multi-clonal P. vivax infections. In order to simulate multiple-clone infections with well-defined proportions of different parasite genotypes, cloned PCR products or patient-derived genomic DNA were artificially mixed. In addition, the performance of these markers was also evaluated by genotyping P. vivax isolates that had infected patients from the Brazilian Amazon. The PCR-capillary electrophoresis-based method (PCR-CE), which offers several advantages, such as high resolution (1 bp), reproducibility in determining fragment size, and a cost-benefit for the analysis of a large number of field samples, was used to genotype all markers [23]. Although this method of quantification is subject to some limitations, many studies have shown that the peak heights correspond to the actual relative proportions of clones in an infection when data are properly normalized [19, 24, 25]. The ability to identify less abundant clones depends on the criteria applied to differentiate minor peak from artifacts, which allows the multiplicity of infection to be properly defined. Two criteria are commonly used to score multiple alleles per locus: cut-off values for minor peak detection of (1) one-fourth or (2) one-third the height of the predominant peak [9, 12, 26–29]. Although the one-third criterion is the most widely used, few studies have evaluated the sensitivity of these criteria for the detection of multi-clonal infections [19]. Here, the results showed the necessity to apply the less stringent one-fourth criterion to increase the detection of multiple-clone infections. Specifically, a minimum panel of four markers was defined to characterize the multiplicity of a P. vivax infection.

This is the first study to show that depending on the type of marker used for P. vivax analysis, a considerable amplification bias is observed. This relationship may have serious implications for the characterization of the complexity of an infection. Moreover, these findings were facilitated by the use of parasite DNA samples with well-defined proportions of each genotype in artificial mixtures as well as the use of molecular markers with different features, such as neutral and non-neutral markers.

Methods

Field isolates and DNA extraction

Fifty-one P. vivax isolates were obtained from the blood of infected patients from the Brazilian Amazon, including 22 samples previously characterized as having multi-clonal infection [9, 11]. The mono-infections were confirmed by 6 to 11 molecular markers described here or elsewhere [9, 11]. DNA was extracted from whole blood samples using the Gentra Puregene Blood Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of René Rachou Research Center (Protocol number 20/2009).

Artificial mixtures of DNA

To simulate multiple-clone infections with a known proportion of each clone, two plasmid DNAs (pDNA), each containing distinct variants of each locus (A-type and B-type alleles), were mixed in different proportions to produce 11 different mixtures prior to PCR amplification and genotyping. To set up mixtures, each pDNA was quantified in a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA), and the number of plasmid copies was estimated as follows: plasmid copy number = [(6.02 × 1023 copies/mol) × DNA quantity (g)]/[DNA length (bp) × 660 (g/mol/bp)]. Two-fold serial dilutions of pDNA were prepared for each experiment, with DNA concentrations ranging from 3.13 × 107 to 1.0 × 109 copies/µL of the plasmid. For all PCR reactions, 1 µL of each plasmid in a specific concentration was added to reaction to produce a curve with varied proportions of pDNA. In addition, mixed genomic DNA (gDNA) samples from two P. vivax-infected patients previously identified as being mono-clonal were also used to simulate multi-clonal infections [9]. To this end, samples with similar parasitaemia (microscopy) and leukocyte counts (leukogram determination) were selected, and the gDNA concentration was determined using a spectrophotometer. The parasite density in samples from P. vivax-infected patients ranged from 3000 to 7500 parasites/µL, as determined by light microscopy. The genomic DNA was two-fold serially diluted (8–0.25 ng), and 1 µL of each sample was added to each PCR reaction. To estimate the relative abundance of alleles in the mixture after genotyping, the ratio between the two peak heights (given in arbitrary fluorescence units) was calculated for each mixture. Data shown represent the average of two independent experiments, and each experiment was analysed in duplicate in an automatic DNA sequencer.

The observed data were normalized according to Havryliuk et al. [17] to allow direct comparisons between expected ratios and observed values. Specifically, the peak height ratios observed in a 1:1 mixture were used as normalization factors in subsequent analyses.

PCR amplification and genotyping of molecular markers

The six loci selected for this study consisted of two microsatellites (PvMS6 and PvMS7), one tandem repeat (MN21), and blocks 2 and 10 of merozoite surface protein-1 (msp1B2 and msp1B10) and merozoite surface protein-3 alpha (msp3α). These fragments were amplified using specific primers and conditions as described previously [10, 11, 34]. The nested approach described by Koepfli et al. [10] was modified to capture more variability and used to amplify block 2 of msp1 and msp3α. The primers used in the nested reaction were changed to the following: msp1B2 (forward primer 5′GACGATATTGGAAAATTGGA3′; reverse primer 5′CTCCTTCAGCACTTTCACGCGCTT3′); and for msp3α (forward primer 5′CCCGCATGAGGAGCCAAACAACTT3′; reverse primer 5′CCTTTGCATTTTTTGCCGCAG3′). For msp1b2, these new primers anneal in a more conserved region of the gene, and the new msp3α primers were designed to amplify a larger and more polymorphic fragment. All forward primers used in the genotyping were conjugated to the fluorescent dye 6-FAM. The following mixture was subjected to nested PCR: 1 μL of PCR product of the first reaction (diluted 1:1000 in H2O), 1 µM of each primer (Integrated DNA Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA), 0.125 mM of dNTPs, 2 μL of 10X Taq polymerase buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 1 U of recombinant Taq polymerase (Invitrogen) in a final volume of 20 μL. The magnesium concentration varied from 3 mM (msp1B2) to 2 mM (msp3α). The cycling parameters were set to the following: 1 cycle at 94 °C for 4 min; 25 cycles consisting of 40 s of denaturation at 94 °C, 30 s of annealing at 64 °C (for msp1B2) or 63 °C (msp3α), and 40 s of elongation at 72 °C; and a final cycle of 10 min at 72 °C.

For capillary electrophoresis, 2 μL of the diluted PCR products (1:20 in H2O) was mixed with the size standard ET-Rox 550 or ET-Rox 900 (Amersham Biosciences) diluted 1:40 in 0.1 % Tween-20 to a final volume of 10 μL. After capillary electrophoresis, alleles were visualized and scored in an automatic DNA sequencer (MegaBACE; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Their lengths and relative abundance (peak heights in electropherograms) were determined using the MegaBACE™ Fragment Profiler version 1.2 software (Amersham Biosciences). For the electropherogram analysis, the minimum peak height was set to 150 arbitrary fluorescence units (rFU). Additionally, cut-off values for minor peak detection of one-fourth or one-third the height of the predominant peak were used to exclude artifact peaks.

Cloning of PCR products

For each locus, two variants differing in size were cloned into the pGEM-T Vector (Promega) or TOPO-TA Cloning Vector (Invitrogen): 305 or 203 bp for PvMS6; 362 or 350 bp for PvMS7; 641 or 692 bp for msp3α; 402 or 429 bp for msp1B2; 252 or 258 bp for msp1B10; 292 or 257 bp for MN21 (Additional file 1). The fragments cloned into the pGEM-T Vector were termed A-type, and those cloned into the TOPO-TA Cloning Vector were termed B-type. The PCR amplicons were cloned according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Recombinant vectors were used to transform the competent Escherichia coli Top10 strain using thermal shock, and the cells were plated in LB agar supplemented with ampicillin (50 μg/mL), X-Gal (1 mg/mL) and IPTG (0.1 mM) [30]. The plasmid DNAs were extracted using a QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen).

Results

Evaluation of amplification bias in artificial mixtures of plasmid DNA

Mixtures of DNA were prepared using known proportions of two different pDNAs (cloning vectors, each containing one of the two variants of a locus studied). Overall, the efficiencies of six genetic markers (two microsatellites, one tandem repeat, and three antigen-coding markers) to detect alleles in artificial mixtures were compared. All six molecular markers accurately identified the correct alleles in samples containing a single clone. However, an amplification bias was detected for most markers in the 1:1 mixtures; specifically, one of the two alleles at a given locus was predominantly amplified (Additional files 2 and 3).

Only three of the six markers (msp1B2, msp1B10 and the tandem repeat MN21) were able to detect the correct proportions of each clone in most of the artificial mixtures (Fig. 1 and Additional file 2). For both msp1 markers, the correspondence between the expected and observed proportions was evident, even for non-normalized data (Additional file 2). Thus, six to seven of ten tested dilutions corresponded to the expected proportions of the two cloned msp1 markers in the infection (Fisher´s exact test, P > 0.05). These results agree with linear regression analyses, which indicated a significant relationship between the actual peak height and the known mixture of pDNA based on high regression values (R2) and a slope close to the expected value of unity for both msp1 markers and MN21 (Additional file 2).

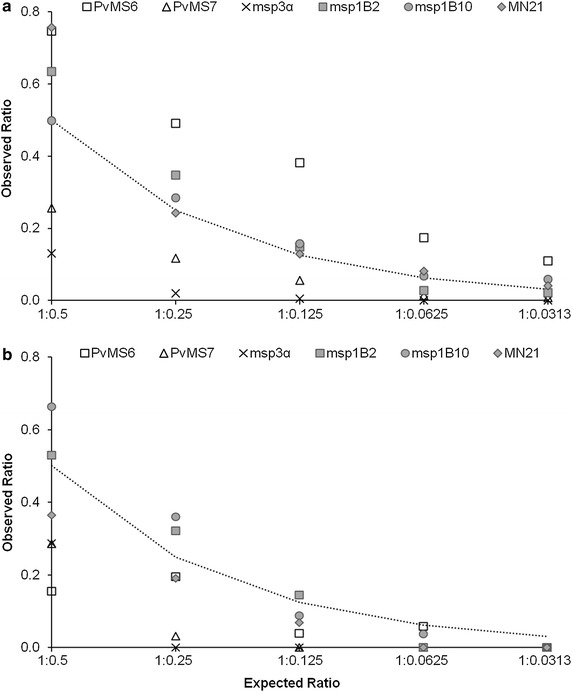

Fig. 1.

Expected and normalized observed ratios of molecular marker alleles amplified from mixtures of cloned DNA with predominance of A-type allele (a) and B-type allele (b). Two microsatellite markers (PvMs6 and PvMS7), one tandem repeat (MN21), and three antigen-coding markers (msp1B2, msp1B10 and msp3α) were PCR amplified and analysed by capillary electrophoresis. The dotted line indicates the expected ratios of peak heights according to the proportion of molecules (cloned DNA) from each allele used as a template for PCR amplification. Data represent the average of two independent experiments

In most mixtures, the correct proportions of the two clones were not accurately determined using the microsatellite markers PvMS6 and PvMS7 (Additional file 2). Nevertheless, these markers were sensitive to the decreased relative abundance of alleles in artificial mixtures, mainly when the A-type allele was predominant (for mixtures ranging from 1:0.5 to 1:0.0313) (Fig. 1a). For PvMS6, the analysis of the non-normalized data showed that the shorter (B-type) allele was preferentially amplified, even when the expected ratio of A-type to B-type alleles was as high as 1:0.125 (Additional file 2). For example, the B-type allele clearly predominated (1:1.49) for this expected ratio (1:0.125). A similar result was observed for mixtures of genomic DNA without cloning (Additional file 4).

Criteria for detection of rare alleles in artificial mixtures of plasmid DNA

Two criteria are frequently used to score rare alleles in multiple-clone infections: (1) the one-third criterion, wherein peak heights of rare alleles are equal or higher than 33 % of the height of the predominant peak, and (2) the one-fourth criterion, in which a cut-off value of 25 % is applied to detect rare alleles. When the one-third criterion was applied, PvMS6 and both msp1 markers detected 36–45 % of multiple infections (Fig. 2). For PvMS6, the use of the one-fourth criterion allowed an increase of 18 % in the detection rate of multiple infections, increasing the overall rate to 54 %. For PvMS7, msp3α and MN21, the multi-clonal parasite rates were below 30 % using either of the cut-off value criteria (25 or 33 %).

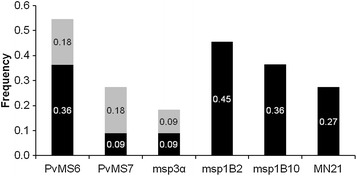

Fig. 2.

Detection of alleles in artificial mixtures of plasmid DNA by applying different criteria for rare allele identification. The frequency of detection of multiple alleles was calculated considering all 11 of the artificial mixtures assayed for each marker. The bars represent the total proportion of infections identified by each marker. Two criteria for minor allele detection were considered: a cut-off value of one-third (colored in black only) or one-fourth (the entire bar, including both black and grey bars), of the height of the predominant peak. The increase in the rate of detection of alleles with one-fourth criterion is highlighted in grey

Based on the tested mixtures, the application of the one-third criterion allowed the detection of the rare alleles up to a dilution of 1:0.0625 (16× diluted), whereas the one-fourth criterion permitted the identification of rare alleles in more unbalanced mixtures (32x diluted) (Additional file 5). Overall, the use of the one-fourth criterion improved the detection rate of multiple infections up to 33 %, as shown for 1:1 mixtures.

Genotyping of Plasmodium vivax isolates from natural infections

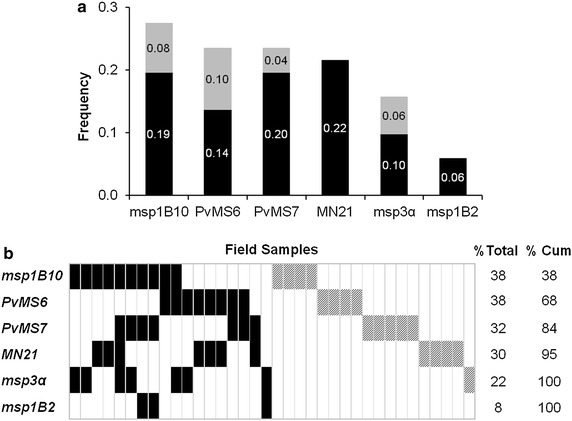

Fifty one samples from the Brazilian Amazon were genotyped with the six markers based on the one-fourth criterion, and 36 (70.6 %) samples were identified as multiple-clone infections, for which at least one locus contained more than one allele. The greatest number of multiple-clone infections was identified using msp1B10 and the microsatellite markers (27 and 24 % of all samples, respectively) (Fig. 3a). Conversely, the msp1B2 marker only identified three (5.9 %) multiple-clone infections. A detailed analysis of the data showed that three additional infections were likely lost by the msp1B2 marker due to a weak fluorescent signal for the rare allele. Moreover, half of the 36 multi-clonal infections defined using the one-fourth criterion were identified using two or more markers (Fig. 3b). msp1B10 identified 38 % of the multiple-clone infections, and this proportion increased to 68 % when msp1B10 was combined with PvMS6 (Fig. 3b). The further addition of PvMS7 and MN21 detected 95 % of the clonal infections. Combined with an analysis based on msp3α, the percentage of identified multi-clonal infections reached 100 %.

Fig. 3.

Detection of multiple-clone infections in field samples. The six markers were genotyped in 51 samples from malaria-endemic area of Brazil. A cut-off value of one-fourth was considered for the analysis. a The frequency of multi-clonal infections was calculated considering both criteria for minor allele detection: a cut-off value of one-third (black bars only) or one-fourth (the entire bar, including both black and grey bars) of the height of the predominant peak. The increase in the rate of detection of multiple-clone infections with the one-fourth criterion is highlighted in grey. b Results of genotyping are shown for the 36 samples with multiple-clone infection detected by one (hatched rectangles) or more markers (rectangles colored in black). Each column represents the same sample genotyped with the six markers. The frequency of multi-clonal infections (% Total) was calculated for each marker. The increase in the number of multiple-clone infections detected, resulting from the combination of two or more markers, is indicated as the cumulative percentage (% Cum)

The potential of each marker to identify polymorphisms can vary considerably and reflects an estimate of the multiplicity of infection. For this part of the study, many samples (22 out 51) that were selected have been previously characterized as multiple-clone infections [9, 11, 34]. Thus, they were not used to determine the rate of multi-clonal infection and the genetic diversity of this parasite population in order to prevent overestimation. To compare the genetic diversity of parasite populations estimated by these markers, the available data for P. vivax from different geographic regions were compiled. The estimates of diversity were highest for the antigen-encoding loci msp1B10 (HE range 0.880–0.902) and msp1B2 (0.813–0.875) (Additional file 6). For the microsatellites PvMS6,PvMS7, and MN21, only data from Brazil were available and the estimate of diversity was lower (mean HE of 0.584, 0.785 and 0.650, respectively).

Discussion

Numerous studies have revealed substantial clonal diversity of Plasmodium within its vertebrate hosts. The characterization of this diversity can influence treatment outcome and elucidate within-host dynamics that may be shaped by several factors, such as host immunity, density-dependent control mechanisms and drug treatment [12, 16, 31]. Furthermore, estimates of within-host variability are relevant to correctly infer evolutionary and population genetics parameters, e.g., selection and recombination [13, 14]. To infer the multiplicity of infection of P. vivax, a panel of suitable molecular markers was defined herein, which included microsatellites, a tandem repeat and antigen-coding genes.

The analysis of artificial DNA mixtures with well-defined proportions of cloned products showed that the commonly used msp1 antigen-coding marker and the tandem repeat MN21 allowed for the estimation of the expected ratio of both alleles in the majority of preparations when using normalized data. Conversely, the microsatellite markers were sensitive to the decreased relative abundance of alleles but, in addition to msp3α, did not accurately estimate the relative clonal proportions in artificial mixtures. For example, a preferential amplification of the shortest allele (with fewest repeats) for PvMS6 was consistently observed in tested dilutions. Accordingly, the preferential amplification of alleles of differing length was previously reported for other microsatellite and antigen-coding loci [32–34]. As indicated by Walsh et al. [27], the extent of preferential amplification is related to the size difference between the allelic PCR products, which was significantly greater for PvMS6 (102 bp). Although not assessed in this study, several other conditions may lead to preferential PCR amplification, such as significant differences in the GC content between alleles, stochastic fluctuation in the presence of low amounts of target DNA molecules [33], and reduced amplification efficiency due to sequence polymorphism in the primer-binding site [35]. Finally, the capillary-based instrument itself may introduce errors in measured relative density of the PCR product for each allele. However, instrument-based errors are unlikely in this study because the results presented here indicate that the method is reproducible. Specifically, replicate experiments yielded similar results, as also reported in other studies [24].

Although some markers, such as the antigen-coding marker msp1 and the tandem repeat, provide an indication of the actual relative proportions of clones in artificial infections, the quantification yielded by the method described herein is subjected to limitations. First, traditional end-point PCR may lead to bias in the template-to-product ratios of target sequences amplified during PCR, particularly for nested PCR, due to increasing numbers of PCR cycles [36, 37]. Thus, the amplification bias observed in the 1:1 mixtures and other dilutions of microsatellites and msp3α may be the result of reaction saturation (plateau phase). At later cycles, the efficiency of PCR eventually declines for a number of reasons, including the exhaustion of reagents and the enzyme, the accumulation of inhibitors and the rehybridization of PCR products, which may interfere with primer binding or extension [37–39]. As a consequence, templates that reach inhibitory concentrations essentially stop amplifying while others continue to efficiently undergo amplification. In addition, the results shown here and by others indicate that accurate quantification requires normalization using a baseline mixture of known proportion to calibrate samples to be analysed [19, 24, 25]. Such normalization restricts the use of this method for experimental infection models. To circumvent these limitations, quantitative PCR (qPCR) or next-generation sequencing (NGS) may be applied to more reliably estimate the relative abundance of clones in an infection. Whereas qPCR is restricted to known single-species infections, like the method described here [34], the applications of NGS are much broader. As recently published for P. falciparum and P. vivax, NGS robustly represents clonal multiplicity and is very promising for drug-resistance or population genetics studies [40–43]. Nevertheless, genomic-level studies remain infeasible in many settings.

Many criteria have been used to differentiate rare alleles from artifacts, such as stutter (peaks that result from DNA strand slippage during PCR at intervals corresponding to nucleotide repeat sizes) or non-specific peaks [11, 11, 26]. Because the sensitivity and specificity of these criteria can vary, comparing studies that applied different criteria is problematic. The present study sought to compare the rates at which multi-clonal infections were detected using the two criteria that are frequently applied to score multiple alleles per locus, i.e., minor peaks ≥33 % or ≥25 % of the height of the predominant peak. Overall, the one-fourth criterion allowed the detection of rare alleles in more unbalanced mixtures and the detection of significantly more alleles, especially for microsatellite markers. The results clearly show that when the one-third criterion is applied for microsatellites, multi-clonal infections may be underestimated, even when the clones were present in similar proportions. This finding was not surprising because several technical difficulties have been described related to the scoring of microsatellite alleles, such as the preferential amplification of alleles with fewer repeats and the higher probability of failing to detect the less abundant alleles [19, 25].

This study examined six loci were of differing molecular features that have been widely used in studies of population genetics and the molecular epidemiology of vivax malaria [9, 12, 11, 34]. These loci included selectively neutral and non-neutral markers on different chromosomes and markers differing in mutation rate (microsatellites, a tandem repeat and an antigen-encoding gene). Thus, most of the variability of P. vivax populations should have been captured, and the within-host diversity should have been effectively characterized in different epidemiological settings. In these areas, several factors may modulate the genetic variability of a locus and/or of complete genomes, such as the malaria transmission rates, selective constraints imposed by the host’s immunity and anti-malarial drug use, and the historical-demographic processes of the parasite population. Compiling the available data on the genetic diversity of P. vivax from different geographic regions higher estimates of diversity were found for antigen-encoding loci and less variable estimates for microsatellites and tandem repeat loci. When samples from the Brazilian Amazon were genotyped for all six markers, msp1B10, microsatellite markers and the tandem repeat MN21 yielded similar results. Interestingly, a significant difference was observed between blocks 2 and 10 of msp1. Whereas msp1B10 was able to detect almost 40 % of the 36 multi-clonal infections identified, msp1B2 allowed the detection of only 6 % of these infections. Moreover, msp3α also showed poor performance in the detection of multiple-clone infections from field samples. Because these loci encode antigens exposed to the immune system, these results suggest that the patterns observed could reflect the different regimes of immune selection that these antigens are exposed to in this population. Notably, 50 % of the multiple-clone infections were detected by only one marker, indicating that adding additional loci may further increase the probability of detecting these infections.

Determining whether a sample is mono-clonal or contains multiple clones of the parasite requires the careful selection of markers because most randomly selected markers may not faithfully depict the true complexity of an infection. Based on the performances of the six markers used here to characterize parasite diversity in both artificial mixtures of clones and in field samples, the combination, including PvMS6, PvMS7, MN21, and msp1B10 were selected for use in molecular epidemiology studies. These markers comprise a panel containing highly informative loci that exhibit genetic variability in all examined P. vivax populations as well as loci that are less sensitive to PCR amplification biases and were able to better characterize the multiplicity of infection. In this study, a PCR-CE was proposed for allele scoring, which has the advantage of allowing the accurate and fast genotyping of a large number of field samples at relatively low cost. Furthermore, a less stringent criterion for rare allele identification significantly increases the sensitivity of this method. Thus, a minimum of one-fourth should be used as a cut-off value for minor peak detection. Although the results described apply to a small subset of alleles and field samples likely contain several unknown alleles, they reveal information about amplification bias, which can be used to identify markers and conditions under which such biases are minimized. Field samples from the Brazilian Amazon region, an area of low and unstable malaria transmission, were used to define the proposed panel. Nevertheless, further characterization is required, especially in regions of high endemicity, where this panel would also provide information about multi-clonal infections due to the high genetic variability of parasite population in such areas.

Conclusions

This study showed that the analysed molecular markers varied in their ability to detect and estimate the relative abundance of different clones in a P. vivax infection, which may bias the estimated of the genetic diversity of the parasite population. Using artificial mixtures of DNA and the genotyping of field isolates from Brazil, four markers (two microsatellites, one tandem repeat and one antigen-encoding gene) were selected based on their ability to characterize the within-host parasite diversity. Moreover, the use of a less stringent criterion is recommended to increase the probability of detecting rare alleles.

Authors’ contributions

TNS and CFAB designed the study. AMS and FCFA performed the experiments. TNS, AMS and FCFA analysed the data. CFAB, LHC and CJFF contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. TNS, CFAB, LHC, and AMS wrote the manuscript; all authors contributed to the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the patients who made this study possible. We thank American Journal Experts for reviewing the manuscript. We also thank the Programme for Technological Development in Tools for Health—PDTIS platform (FIOCRUZ) for DNA sequencing facilities. CJF, LHC and CAB thank CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development) for the research scholarship support. TNS thanks FIOCRUZ/CNPq for the research scholarship support. AMS and FCA thank FAPEMIG for PhD scholarship support. This study has financial support from FAPEMIG (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do estado de Minas Gerais) and CNPq.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

- msp1B2

block 2 of merozoite surface protein 1 gene

- msp1B10

block 10 of merozoite surface protein 1 gene

- msp3α

merozoite surface protein 3 alpha gene

- PCR-CE

PCR-capillary electrophoresis-based method

- PCR-RFLP

PCR-Restriction fragment length polymorphism

- pDNA

DNA plasmid

- gDNA

genomic DNA

- HE

virtual expected heterozygosity

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- rFU

arbitrary fluorescence units

Additional files

Additional file 1. Allele frequencies (%) and genetic diversity analysis of molecular markers of Plasmodium vivax isolates from Brazil.

Additional file 2. Expected and observed ratio of alleles amplified from 11 artificial mixtures of plasmid DNA. The relative abundance of alleles was estimated as the ratio between the heights of the peaks (measured in arbitrary fluorescence units).

Additional file 3. Relative abundance of alleles of the six molecular markers in the mixtures of plasmid DNA. The relative abundance of alleles was estimated as the ratio between the heights of the peaks for non-normalized data: A-type allele (in grey) and B-type allele (black).

Additional file 4. Relative abundance of Plasmodium vivax molecular marker alleles amplified from mixtures of genomic DNA samples from two Plasmodium vivax-infected patients.

Additional file 5. Ratio of rare to predominant alleles in the artificial mixtures of plasmid DNA.

Additional file 6. Summary of previous studies reporting the genetic diversity and multiplicity of infection of Plasmodium vivax.

Contributor Information

Aracele M. de Souza, Email: aracelesouza@cpqrr.fiocruz.br

Flávia C. F. de Araújo, Email: flaviac@cpqrr.fiocruz.br

Cor J. F. Fontes, Email: corfontes@gmail.com

Luzia H. Carvalho, Email: lhcarvalho@cpqrr.fiocruz.br

Cristiana F. A. de Brito, Email: cristiana@cpqrr.fiocruz.br

Taís N. de Sousa, Email: tais@cpqrr.fiocruz.br

References

- 1.Battle KE, Gething PW, Elyazar IR, Moyes CL, Sinka ME, Howes RE, et al. The global public health significance of Plasmodium vivax. Adv Parasitol. 2012;80:1–111. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-397900-1.00001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gething PW, Elyazar IR, Moyes CL, Smith DL, Battle KE, Guerra CA, et al. A long neglected world malaria map: Plasmodium vivax endemicity in 2010. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Price RN, von Seidlein L, Valecha N, Nosten F, Baird JK, White NJ. Global extent of chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium vivax: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:982–991. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70855-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lacerda MV, Fragoso SC, Alecrim MG, Alexandre MA, Magalhaes BM, Siqueira AM, et al. Postmortem characterization of patients with clinical diagnosis of Plasmodium vivax malaria: to what extent does this parasite kill? Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:e67–e74. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tjitra E, Anstey N, Sugiarto P, Warikar N, Kenangalem E, Karyana M, et al. Multidrug-resistant Plasmodium vivax associated with severe and fatal malaria: a prospective study in Papua, Indonesia. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Douglas NM, Pontororing GJ, Lampah DA, Yeo TW, Kenangalem E, Poespoprodjo J, et al. Mortality attributable to Plasmodium vivax malaria: a clinical audit from Papua, Indonesia. BMC Med. 2014;12:217. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0217-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells TN, Burrows JN, Baird JK. Targeting the hypnozoite reservoir of Plasmodium vivax: the hidden obstacle to malaria elimination. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alonso PL, Brown G, Arevalo-Herrera M, Binka F, Chitnis C, Collins F, et al. A research agenda to underpin malaria eradication. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orjuela-Sanchez P, Sa JM, Brandi MC, Rodrigues PT, Bastos MS, Amaratunga C, et al. Higher microsatellite diversity in Plasmodium vivax than in sympatric Plasmodium falciparum populations in Pursat, Western Cambodia. Exp Parasitol. 2013;134:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2013.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreira MU, Karunaweera ND, da Silva-Nunes M, da Silva NS, Wirth DF, Hartl DL. Population structure and transmission dynamics of Plasmodium vivax in rural Amazonia. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1218–1226. doi: 10.1086/512685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunawardena S, Karunaweera ND, Ferreira MU, Phone-Kyaw M, Pollack RJ, Alifrangis M, et al. Geographic structure of Plasmodium vivax: microsatellite analysis of parasite populations from Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:235–242. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunawardena S, Ferreira MU, Kapilananda GM, Wirth DF, Karunaweera ND. The Sri Lankan paradox: high genetic diversity in Plasmodium vivax populations despite decreasing levels of malaria transmission. Parasitology. 2014;141:880–890. doi: 10.1017/S0031182013002278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor AR, Flegg JA, Nsobya SL, Yeka A, Kamya MR, Rosenthal PJ, et al. Estimation of malaria haplotype and genotype frequencies: a statistical approach to overcome the challenge associated with multiclonal infections. Malar J. 2014;13:102. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hastings IM, Smith TA. MalHaploFreq: a computer programme for estimating malaria haplotype frequencies from blood samples. Malar J. 2008;7:130. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takala SL, Coulibaly D, Thera MA, Dicko A, Smith DL, Guindo AB, et al. Dynamics of polymorphism in a malaria vaccine antigen at a vaccine-testing site in Mali. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e93. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenhouse B, Dokomajilar C, Hubbard A, Rosenthal PJ, Dorsey G. Impact of transmission intensity on the accuracy of genotyping to distinguish recrudescence from new infection in antimalarial clinical trials. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3096–3103. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00159-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SA, Yeka A, Nsobya SL, Dokomajilar C, Rosenthal PJ, Talisuna A, et al. Complexity of Plasmodium falciparum infections and antimalarial drug efficacy at 7 sites in Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1160–1163. doi: 10.1086/501473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlton J, Adams J, Silva J, Bidwell S, Lorenzi H, Caler E, et al. Comparative genomics of the neglected human malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax. Nature. 2008;455:757–763. doi: 10.1038/nature07327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Havryliuk T, Orjuela-Sánchez P, Ferreira M. Plasmodium vivax: microsatellite analysis of multiple-clone infections. Exp Parasitol. 2008;120:330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imwong M, Nair S, Pukrittayakamee S, Sudimack D, Williams JT, Mayxay M, et al. Contrasting genetic structure in Plasmodium vivax populations from Asia and south America. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37:1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Havryliuk T, Ferreira M. A closer look at multiple-clone Plasmodium vivax infections: detection methods, prevalence and consequences. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:67–73. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762009000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joshi H, Prajapati S, Verma A, Kang’a S, Carlton J. Plasmodium vivax in India. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selkoe KA, Toonen RJ. Microsatellites for ecologists: a practical guide to using and evaluating microsatellite markers. Ecol Lett. 2006;9:615–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ford AF, Vardo-Zalik AM, Schall JJ. Relative clonal density of malaria parasites in mixed-genotype infections: validation of a technique using microsatellite markers for Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium mexicanum. J Parasitol. 2010;96:908–913. doi: 10.1645/GE-2499.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vardo-Zalik AM, Ford AF, Schall JJ. Detecting number of clones, and their relative abundance, of a malaria parasite (Plasmodium mexicanum) infecting its vertebrate host. Parasitol Res. 2009;105:209–215. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1385-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson TJ, Su XZ, Bockarie M, Lagog M, Day KP. Twelve microsatellite markers for characterization of Plasmodium falciparum from finger-prick blood samples. Parasitology. 1999;119(Pt 2):113–125. doi: 10.1017/S0031182099004552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson T, Haubold B, Williams J, Estrada-Franco J, Richardson L, Mollinedo R, et al. Microsatellite markers reveal a spectrum of population structures in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:1467–1482. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chenet SM, Tapia LL, Escalante AA, Durand S, Lucas C, Bacon DJ. Genetic diversity and population structure of genes encoding vaccine candidate antigens of Plasmodium vivax. Malar J. 2012;11:68. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van den Eede P, Erhart A, Van der Auwera G, Van Overmeir C, Thang ND, le Hung X, et al. High complexity of Plasmodium vivax infections in symptomatic patients from a rural community in central Vietnam detected by microsatellite genotyping. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:223–227. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishimura A, Morita M, Nishimura Y, Sugino Y. A rapid and highly efficient method for preparation of competent Escherichia coli cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6169. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Portugal S, Carret C, Recker M, Armitage AE, Goncalves LA, Epiphanio S, et al. Host-mediated regulation of superinfection in malaria. Nat Med. 2011;17:732–737. doi: 10.1038/nm.2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenhouse B, Myrick A, Dokomajilar C, Woo J, Carlson E, Rosenthal P, et al. Validation of microsatellite markers for use in genotyping polyclonal Plasmodium falciparum infections. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:836–842. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walsh P, Erlich H, Higuchi R. Preferential PCR amplification of alleles: mechanisms and solutions. PCR Methods Appl. 1992;1:241–250. doi: 10.1101/gr.1.4.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu S, Mu J, Jiang H, Su XZ. Effects of Plasmodium falciparum mixed infections on in vitro antimalarial drug tests and genotyping. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:178–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwok S, Kellogg DE, McKinney N, Spasic D, Goda L, Levenson C, et al. Effects of primer-template mismatches on the polymerase chain reaction: human immunodeficiency virus type 1 model studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:999–1005. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.4.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polz MF, Cavanaugh CM. Bias in template-to-product ratios in multitemplate PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3724–3730. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3724-3730.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki MT, Giovannoni SJ. Bias caused by template annealing in the amplification of mixtures of 16S rRNA genes by PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:625–630. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.625-630.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kainz P. The PCR plateau phase—towards an understanding of its limitations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1494:23–27. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4781(00)00200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathieu-Daude F, Welsh J, Vogt T, McClelland M. DNA rehybridization during PCR: the ‘Cot effect’ and its consequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2080–2086. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.11.2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manske M, Miotto O, Campino S, Auburn S, Almagro-Garcia J, Maslen G, et al. Analysis of Plasmodium falciparum diversity in natural infections by deep sequencing. Nature. 2012;487:375–379. doi: 10.1038/nature11174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robinson T, Campino SG, Auburn S, Assefa SA, Polley SD, Manske M, et al. Drug-resistant genotypes and multi-clonality in Plasmodium falciparum analysed by direct genome sequencing from peripheral blood of malaria patients. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin JT, Hathaway NJ, Saunders DL, Lon C, Balasubramanian S, Kharabora O, et al. Using amplicon deep sequencing to detect genetic signatures of Plasmodium vivax relapse. J Infect Dis. 2015;pii:jiv142. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor SM, Parobek CM, Aragam N, Ngasala BE, Martensson A, Meshnick SR, et al. Pooled deep sequencing of Plasmodium falciparum isolates: an efficient and scalable tool to quantify prevailing malaria drug-resistance genotypes. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1998–2006. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zakeri S, Safi N, Afsharpad M, Butt W, Ghasemi F, Mehrizi AA, et al. Genetic structure of Plasmodium vivax isolates from two malaria endemic areas in Afghanistan. Acta Trop. 2010;113:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]