Abstract

Objective

Lung cancer is still the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. However, most elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have been undertreated and the outcome related to age is controversial. A retrospective analysis was conducted for advanced NSCLC in order to investigate the characteristics and prognosis of older patients.

Methods

Medical records were collected from 165 patients with NSCLC (stages IIIA–IIIB) who had been treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT) or radiotherapy from January 2009 to January 2011. The cases were divided into two age groups 1) patients ≥70 years old; 2) patients <70 years old. There were 73 patients in group I, 92 in group II. Patient characteristics, treatment toxicities, and prognosis were evaluated.

Results

Of the 165 patients analyzed, 34 patients (34/73) in group I received concurrent CRT while 47 (47/92) in group II completed that treatment. No significant difference was observed in the reason for patients who discontinued CRT in two groups (P>0.05). In the patients with adenocarcinoma, more cases were found in group II than that in group I; the more squamous cell carcinoma and the more smokers with squamous cell carcinoma were seen in older group (P<0.05). With a median follow-up of 20.5 months, the 1-year survival for group I and II were 49.3% and 40.2% respectively (P=0.243). Two-year survival for the two groups was 20.5% and 16.3% (P=0.483); 3-year survival was 9.6% and 9.8% (P=0.967). There was no significant difference between two groups statistically in survival by univariate analysis (P>0.05). The therapy-related toxicities in group I seem to be similar to the group II (P>0.05).

Conclusion

More adenocarcinoma patients were found in youthful lung cancer and the more smokers with squamous cell carcinoma were seen in older group. Age is not the important factor for the selection and allocation of treatment in advanced NSCLC. The same prognosis and toxicities had been shown in older and young. Age may not be an independent increased risk of death in advanced NSCLC.

Keywords: advanced non-small-cell lung cancer, age, prognosis

Introduction

Lung cancer remains the most frequent cause of cancer-related death worldwide nowadays.1 Of these deaths, non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for over 85% with a 5-year survival rate of 10%–12%.2,3 Among them, elderly person make up a substantial part of NSCLC. The number is expected to increase and estimated to represent 70% of all with cancer by 2030.4 Despite the quickly increasing incidence of elderly patients, the elderly lung cancer patients have been significantly underrepresented in clinical trials.5 Because the advanced age has often been associated with a poor performance status and comorbidities, the advanced age has been a prevalent cause for not administering treatment according to the guidelines.6,7 Some trials suggested that elderly patients have a poor prognosis and unresectable tumor.8 Other studies have showed that lung cancer in young patients may constitute an entity with distinct clinicopathologic characteristics.9,10 Thus, it is still controversial whether younger patients have better or worse outcomes compared with the older counterparts with lung cancer.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Among the patients with NSCLC, when diagnosed, around 60%–65% have either metastatic disease or unresectable.11 Lung cancer usually affects patients in their 60s and 70s.12,13 However, data on management of stages III and IV in NSCLC are insufficient, especially in the elderly.14 Most elderly patients with advanced NSCLC do not receive chemotherapy or have been undertreated, since they are still underrepresented in clinical trials.15–17 Another problem has been that few of the existing trials concerning this patient group have adhered to the standard treatment.18,19 Few elderly patients meet the inclusion criteria although most studies do not have a superior age limit.20 Compared to reality, not only is the data on elderly patients rare, but also the number of eligible elderly patients is very low. Thus, more research in older populations are necessary that could explain a difference in prognosis.

The determination of the outcome is complicated, including the risk of death from competing stage of disease, method of treatment, histologic type, and age-related illnesses. The outcome of NSCLC related to age is controversial. Therefore, the aim of this retrospective study was to compare elderly patients with their younger counterparts with advanced NSCLC. We assessed the patients’ characteristics, treatment, prognosis, and toxicities and also aimed to evaluate if there are certain different factors between the older and younger patients.

Materials and methods

Definition of the elderly subgroup and study aims

The elderly was defined as patients aged ≥70 years in accordance with common practice.5,8,18,21,22 Age was a stratification factor specified in the original protocol. The aims of this analysis were to 1) explore the characteristics, treatment, prognosis, and safety of therapy in elderly patients (aged ≥70 years) with advanced NSCLC; 2) compare the results with those of younger patients.

Patients

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University. Data was collected retrospectively from the records of 165 consecutive patients with advanced lung cancer who had been treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT) or radiotherapy from January 2009 to January 2011. They all had provided written informed consent for the treatment.

The inclusion criteria were histological or cytological proof of NSCLC, stage IIIA or stage IIIB, good performance status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] 0 [asymptomatic], or 1 [symptomatic but ambulatory]), no connective tissue disease, no uncontrolled concomitant disease, and no prior irradiation. The patients were divided into two groups 1) patients ≥70 years old; 2) patients <70 years old. There were 73 in group I, 92 in group II.

Radiation therapy

External beam radiation therapy was delivered using a 10 MV photon beam from a linear accelerator in a conventional fraction (2 Gy/fraction, 5 fractions/week). A total dose of 60 Gy was administered. Patients were seen weekly for a complete blood count test. If the white blood cell count fell below 1,000/mm3 or if platelets fell below 50,000/mm3, external beam radiation therapy was interrupted and was resumed once counts rose above these levels.

Chemotherapy

Either cisplatin–gemcitabine or cisplatin–vinorelbine was used. Vinorelbine was given in a dose of 25 mg/m2 on day 1 and day 8, gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 on day 1 and day 8, and cisplatin (40 mg/m2/day for 3 days) every 3 weeks for two cycles; up to two to six cycles. Chemotherapy was stopped if creatinine clearance was <30 mL/min, and interrupted if platelets were ≤100,000/mm3, or the total white blood cell count was ≤4,000/mm3.

Toxicity

During treatment, toxicities were assessed in accordance with the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria of Adverse Events version 3.0: 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe; and 4, life-threatening or disabling.23

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 17.0 software. The Kaplan–Meier approach and the log-rank test were used to compare survival profiles between the two patient groups. P<0.05 was considered significant for all statistical analysis.

Follow-up

After completion of treatment, patients were followed-up at 1-month intervals for 3 months, 3-month intervals for 1 year, 6-month intervals for 3 years, and annually thereafter. Investigations included complete blood count, chest CT, head/neck CT where necessary, and bone scan.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are described in Table 1. In total, 165 patients were included from January 2009 to January 2011. Four patients had a family history of lung cancer and eight patients had a family history of other malignancies. The mean age of the patients at the time of diagnosis were 71.8±0.5 years (range 70–85 years) in group I and 40.5±0.7 (range 21–69 years) years old in group II (P<0.05). In the older group, there were 43 (58.9%) male and 30 (41.1%) female patients. Thirty-eight (52.1%) smokers were identified (P>0.05 vs 40 [43.5%] patients in group II). Pathological results showed 95 adenocarcinoma patients (31 [42.5%], group I; 64 [69.6%], group II); squamous cell carcinoma in 53 patients (32 [43.8%], group I; 21 [22.8%], group II) and other in the remaining. But in the patients with adenocarcinoma, more cases were found in group II than that in group I; the more squamous cell carcinoma and the more smokers with squamous cell carcinoma were seen in older group (P<0.05). Seventy-five patients were diagnosed in stage IIIA (35 [47.9%], group I; 40 [43.5%], group II) and 90 patients in stage IIIB (38 [52.1%], group I; 52 [56.5%], group II). Of the 165 patients analyzed, 34 patients (34/73) in group I received concurrent CRT while 47 (47/92) in group II completed that treatment.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients by treatment group (n, %)

| Characteristic | Group Ia 73 | Group IIb 92 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG performance status | |||

| 0 or 1 | 60/73 (82.2%) | 71/92 (77.2%) | 0.429 |

| >1 | 13/73 (17.8%) | 21/92 (22.8%) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 43/73 (58.9%) | 64/92 (69.6%) | 0.154 |

| Female | 30/73 (41.1%) | 28/92 (30.4%) | |

| Stage | |||

| IIIA | 35/73 (47.9%) | 40/92 (43.5%) | 0.567 |

| IIIB | 38/73 (52.1%) | 52/92 (56.5%) | |

| Histologic type | |||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 32/73 (43.8%) | 21/92 (22.8%) | 0.002 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 31/73 (42.5%) | 64/92 (69.6%) | |

| Other | 10/73 (13.7%) | 7/92 (7.6%) | |

| Initial treatment | |||

| R | 39/73 (53.4%) | 45/92 (48.9%) | 0.565 |

| R+C | 34/73 (46.6%) | 47/92 (51.1%) | |

| Smoking status | |||

| Smoker | 38/73 (52.1%) | 40/92 (43.5%) | 0.273 |

| Nonsmoker | 35/73 (47.9%) | 52/92 (56.5%) | |

Notes:

Patients ≥70 years old, n=73.

Patients <70 years old, n=92.

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; R, radiotherapy; R+C, radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

The reason for patients who discontinued CRT were disease progression (12 patients in group I; five patients in group II), unacceptable toxicity (seven patients in group I; six patients in group II), undercurrent disease (five patients in group I; three patients in group II), patient request (five patients in group I; four patients in group II), and other (seven patients in group I; seven patients in group II). No significant difference was observed in two groups (P>0.05).

Survival

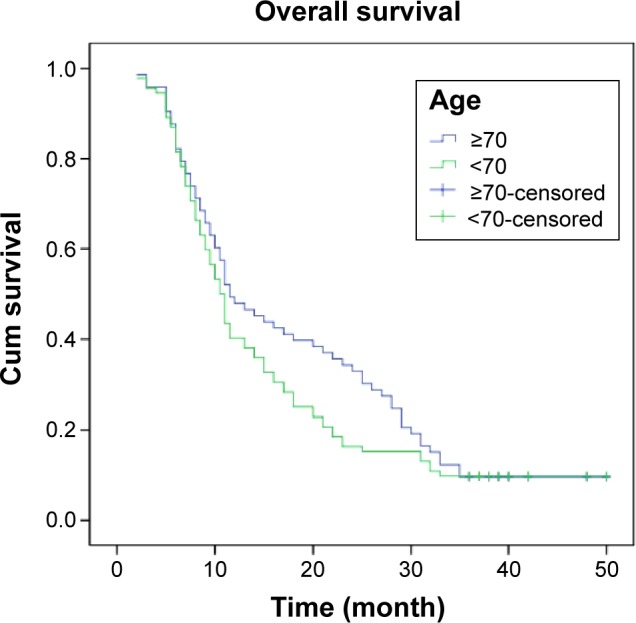

With a median follow-up of 20.5 months, the 1-year survival for group I and II were 49.3% and 40.2% respectively (P=0.243). Two-year survival for the two groups was 20.5% and 16.3% (P=0.483); 3-year survival was 9.6% and 9.8% (P=0.967). There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in survival as shown by univariate analysis (P>0.05) (Figure 1 and Table 2).

Figure 1.

Survival analysis in locally advanced lung cancer, stratified by groups I and II (P>0.05).

Table 2.

Survival rates stratified by patient group (n, %)

| Group Ia | Group IIb | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-year survival | 36/73 (49.3%) | 37/92 (40.2%) | 0.243 |

| 2-year survival | 15/73 (20.5%) | 15/92 (16.3%) | 0.483 |

| 3-year survival | 7/73 (9.6%) | 9/92 (9.8%) | 0.967 |

Notes:

Patients ≥70 years old, n=73.

Patients <70 years old, n=92.

Other clinical parameters, including ECOG performance, sex, histologic type, and smoking status, significantly affected the survival rates in the evaluated patients (P in log-rank was <0.05). The Cox regression led to a model containing three independent terms that were predictive of overall and progression-free survival: peritumoral lymphatic vessel density, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage, and pathology type (P<0.05). On multivariate analysis, ECOG performance was the only clinical factor with a significant effect (95% confidence interval, 0.019–0.085; P<0.01).

Toxicities

Anemia and neutropenia were found in eight and 47 patients, respectively. In group I, four and 20 patients developed anemia and neutropenia, while in group II, four and 27 patients developed these side effects. No differences in acute hematologic toxicity between the two patient groups was found (P=0.737 for anemia; P=0.783 for neutropenia). Twelve patients developed thrombocytopenia. The incidence of it was 6.8%, and 7.6% in group I and II respectively (P=0.852). There was no statistical difference between the patient groups in terms of the incidence of radiation-related esophagitis and pneumonitis (P=0.626, P=0.520) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Toxicities stratified by patient group

| Group Ia | Group IIb | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anemia | 4/73 (5.5%) | 4/92 (4.3%) | 0.737 |

| Neutropenia | 20/73 (27.4%) | 27/92 (29.3%) | 0.783 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 5/73 (6.8%) | 7/92 (7.6%) | 0.852 |

| Esophagitis | 24/73 (32.9%) | 27/92 (29.3%) | 0.626 |

| Pneumonitis | 13/73 (17.8%) | 13/92 (14.1%) | 0.520 |

Notes:

Patients ≥70 years old, n=73.

Patients <70 years old, n=92.

Discussion

In the older group, clinicopathologic features including sex distribution, differentiation of cancer cells and stage were comparable with those in the younger group. Some previous studies suggested that adenocarcinoma is common in nonsmoker and female patients, and presents a predominance of adenocarcinoma, the advanced stage at diagnosis, and thus a generally poor prognosis.12,13 Many studies have shown that lung cancer in the young had its different clinicopathologic characteristics with distinct sex distribution, pathological features, stage at diagnosis, and prognosis.12,13 In this study, more adenocarcinoma patients were found in youthful lung cancer. This is in accordance with the reported data. Moreover, in our study, the more squamous cell carcinoma and the more smoker with squamous cell carcinoma were seen in older group, which could also confirmed that lung cancer is always associated with tobacco use.

Based on some research, age is usually to be seen as an important factor for the selection and allocation of treatment, especially in advanced disease.24–26 Age especially influences the choice of therapy: chemoradiation or radiotherapy. It is well known that the elderly are less likely to receive aggressive therapy. But in our study, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in therapy, suggesting that the two groups were equal about the treatment. This finding is different from other study that reported more elderly patients discontinued treatment than younger patients and age seems to be a powerful predictor.13 Moreover, our data showed that overall survival times were similar in both groups, although several researches suggested that younger patients had a better outcome than their older counterparts with lung cancer.9,12 It may reflect a different biological behavior of the tumor, and correlate with both more adenocarcinoma in our younger patients and similar treatment in both groups. Indeed, some study suggested that platinum-based therapy in advanced NSCLC patients offered an advantage, with a 10% improvement in 1-year survival.27 The association of a platinum compound with a third-generation agent improves survival.28,29 It seems to be the most effective therapeutic choice in advanced NSCLC. With a platinum compound, doublet chemotherapy is considered to be the standard care for elderly patients.14 In this study, concomitant CRT may explain that they have survival similar to the youngest group.

In addition, elderly patients with advanced NSCLC did not experience more toxicity and side effects from CRT and radiotherapy than younger patients in this research, such as acute hematologic toxicity, radiation-induced esophagitis, and pneumonitis, which seems to be in contrast with the previous study.30 The elderly patients discontinuing treatment is not always due to the side effects of therapy. In fact, there are some other reasons. First, prolonged hospital stay was associated with therapy refusal.31 Pain is subjectively rated as worse during hospitalization and their daily routine is disrupted after the elderly are removed from their familiar environment.32 Second, elderly NSCLC smokers are highly accustomed to smoking. Giving up tobacco may be more difficult than it would be for younger patients. From previous studies, patients who discontinued therapy were former smokers or smokers.31 Finally, many elderly patients failed to adjust to the behavioral necessary changes for the therapy. In some cases, in order to maintain the previous habits as long as possible, the elderly may discontinue treatment.31 The behavioral changes required by antineoplastic treatment often do not allow the elderly to maintain the usual activities they performed prior to initiation of treatment. Some clinical research states that NSCLC is related to psychological consequences.33 Therefore, family and social support are more needed by the elderly.

In a word, a multidisciplinary team is needed that can support elderly cancer patients throughout therapy, encourage the elderly patient to continue therapy and provide psychological, medical help. The findings of this study have really provided a brand new idea and increased attention should be given to the elderly patient. Therefore, the development of age-specific guidelines may be warranted and the clinical impressions should be confirmed, with which to move forward in developing the study for elderly.

However, there are some limitations in this study. First, in fact, some patients with stage IIIA/B lung cancer refused chemoradiation or radiotherapy because of economic factor/religious beliefs in outpatient service and was not in hospital; so the patients who were selected undergoing chemoradiation or radiotherapy in hospital were consecutive; maybe these small proportion of patients not undergoing therapy resulted in affected a strong selector for the fittest patients among this age group and the result was affected. Second, the study’s results are limited by its retrospective design and the data from a single institution. Finally, our results would be more attractive if we could discuss the molecular characteristics of lung cancer related to age. Further research about the older patients with lung cancer should be anticipated in the future.

Conclusion

More adenocarcinoma patients were found in youthful lung cancer and the more smokers with squamous cell carcinoma were seen in older group. Age is not the important factor for the selection and allocation of treatment in advanced NSCLC. The same prognosis and toxicities had been shown in old and young age-groups. Age may not be an independent increased risk of death.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of People’s Republic of China (No 81301937) and the International Cooperation Foundation of Shaanxi Province of People’s Republic of China (No 2013KW-27-03).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberg AJ, Ford JG, Samet JM. American College of Chest Physicians. Epidemiology of lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition) Chest. 2007;132(3 Suppl):29S–55S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iachina M, Green A, Jakobsen E. The direct and indirect impact of comorbidity on the survival of patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a combination of survival, staging and resection models with missing measurements in covariates. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e003846. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2758–2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sacher AG, Le LW, Leighl NB, Coate LE. Elderly patients with advanced NSCLC in phase III clinical trials: are the elderly excluded from practice-changing trials in advanced NSCLC? J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:366–368. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31827e2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanco JAG, Toste IS, Alvarez RF, Cuadrado GR, Gonzalvez AM, Martín IJ. Age, comorbidity, treatment decision and prognosis in lung cancer. Age Ageing. 2008;37:715–718. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Rijke JM, Schouten LJ, Velde ten GPM, et al. Influence of age, comorbidity and performance status on the choice of treatment for patients with non-small cell lung cancer; results of a population-based study. Lung Cancer. 2004;46:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strøm HH, Bremnes RM, Sundstrøm SH, et al. How do elderly poor prognosis patients tolerate palliative concurrent chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer stage III? a subset analysis from a clinical phase III trial. Clin Lung Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2014.08.005. S1525–7304(14)00236–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radzikowska E, Roszkowski K, Głaz P. Lung cancer in patients under 50 years old. Lung Cancer. 2001;33:203–211. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramalingam S, Pawlish K, Gadgeel S, Demers R, Kalemkerian GP. Lung cancer in young patients: analysis of a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:651–657. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kowalski DM, Krzakowski M. New agents in chemotherapy of disseminated non-small cell lung cancer – real benefits. Wspolczesna Onkol. 2001;5:278–284. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subramanian J, Morgensztern D, Goodgame B, et al. Distinctive characteristics of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in the young: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:23–28. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c41e8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye T, Pan Y, Wang R, et al. Analysis of the molecular and clinicopatho-logic features of surgically resected lung adenocarcinoma in patients under 40 years old. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(10):1396–1402. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.08.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss J, Langer C. Treatment of lung cancer in the elderly patient. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:802–809. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1358560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidoff AJ, Tang M, Seal B, Edelman MJ. Chemotherapy and survival benefit in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2191–2197. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beckett P, Callister M, Tata LJ, et al. Clinical management of older people with non-small cell lung cancer in England. Thorax. 2012;67:836–839. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meoni G, Cecere FL, Lucherini E, Di Costanzo F. Medical treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer in elderly patients: a review of the role of chemotherapy and targeted agents. J Geriatr Oncol. 2013;4:282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gridelli C. Lung cancer: locally advanced NSCLC in the elderly: which treatment? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:434–435. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wisnivesky JP, Strauss GM. Treating elderly patients with stage III NSCLC. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:650–651. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70178-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maione P, Rossi A, Sacco PC, Bareschino MA, Schettino C. Treating advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the elderly. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2010;2:251–260. doi: 10.1177/1758834010366707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gore E, Movsas B, Santana-Davila R, Langer C. Evaluation and management of elderly patients with lung cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2012;22:304–310. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atagi S, Kawahara M, Yokoyama A, et al. Thoracic radiotherapy with or without daily low-dose carboplatin in elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial by the Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG0301) Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:671–678. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Cancer Institute . Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. Version 3.0. DCTD, NCI, NIH, NHHH. Rockville: National Cancer Institute; [Accessed March 31, 2003]. Available from: http://cteo.cancer.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodheart M, Jacobson G, Smith BJ, Zhou L. Chemoradiation for invasive cervical cancer in elderly patients: outcomes and morbidity. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18(1):95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright JD, Gibb RK, Geevarghese S, et al. Cervical carcinoma in the elderly: an analysis of patterns of care and outcome. Cancer. 2005;103(1):85–91. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao Y, Ma JL, Gao F, Song LP. The evaluation of older patients with cervical cancer. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:783–788. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S45613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D’Addario G, Pintilie M, Leighl NB, Feld R, Cerny T, Shepherd FA. Platinum-based versus non-platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of the published literature. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2926–2936. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gridelli C, Gallo C, Shepherd FA, et al. Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine compared with cisplatin plus vinorelbine or cisplatin plus gemcitabine for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial of the Italian GEMVIN Investigators and the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3025–3034. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:92–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gridelli C, Rossi A, Maione P. Challenges treating older non-small cell lung cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(suppl 7):vii109–vii113. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leppert W, Turska A, Majkowicz M, Dziegielewska S, Pankiewicz P, Mess E. Quality of life in patients with advanced lung cancer treated at home and at a palliative care unit. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2012;29:379–387. doi: 10.1177/1049909111426135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alexa T, Lavinia A, Luca A, Miron L, Alexa ID. Incidence of chemotherapy discontinuation and characteristics of elderly patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with platinum-based doublets. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2014;18:340–343. doi: 10.5114/wo.2014.45293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farbicka P, Nowicki A. Palliative care in patients with lung cancer. Contemp Oncol. 2013;17:238–245. doi: 10.5114/wo.2013.35033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]