Abstract

CTNNB1 mutations or APC abnormalities have been observed in ~85% of desmoids examined by Sanger sequencing and are associated with Wnt/β-catenin activation. We sought to identify molecular aberrations in ‘wild-type’ tumors (those without CTNNB1 or APC alteration) and to determine their prognostic relevance. CTNNB1 was examined by Sanger sequencing in 117 desmoids; a mutation was observed in 101 (86%) and 16 were ‘wild-type’. ‘Wild-type’ status did not associate with tumor recurrence. Moreover, in unsupervised clustering based on U133A-derived gene expression profiles, ‘wild-type’ and mutated tumors clustered together. Whole-exome sequencing of eight of the ‘wild-type’ desmoids revealed that three had a CTNNB1 mutation that had been undetected by Sanger sequencing. The mutation was found in a mean 16% of reads (vs 37% for mutations identified by Sanger). Of the other five ‘wild-type’ tumors sequenced, two had APC loss, two had chromosome 6 loss, and one had mutation of BMI1. The finding of low-frequency CTNNB1 mutation or APC loss in ‘wild-type’ desmoids was validated in the remaining eight ‘wild-type’ desmoids; directed miSeq identified low-frequency CTNNB1 mutation in four and comparative genomic hybridization identified APC loss in one. These results demonstrate that mutations affecting CTNNB1 or APC occur more frequently in desmoids than previously recognized (111 of 117; 95%), and designation of ‘wild-type’ genotype is largely determined by sensitivity of detection methods. Even true CTNNB1 wild-type tumors (determined by next-generation sequencing) may have genomic alterations associated with Wnt activation (chromosome 6 loss/BMI1 mutation), supporting Wnt/β-catenin activation as the common pathway governing desmoid initiation.

Keywords: Desmoid, fibromatosis, β-catenin, CTNNB1 mutation

INTRODUCTION

Desmoid-type fibromatosis represents a clonal proliferation arising from mesenchymal stem cell progenitors (Alman, et al. 1997a; Wu, et al. 2010). They are diagnosed in approximately 1000 patients in the United States each year. Desmoids have no metastatic potential, but can be locally aggressive, causing pain or intestinal obstruction and fistulization (Lewis, et al. 1999). For this reason, surgical resection has been the ‘gold standard’ of treatment. However, aggressive attempts at complete resection in many cases cause significant morbidity, and rates of local recurrence following surgery are as high as 70% in some series (Markhede, et al. 1986; Easter and Halasz 1989; Lopez, et al. 1990; Higaki, et al. 1995; Lewis, et al. 1999; Merchant, et al. 1999).

In the majority of desmoids, tumorigenesis is thought to be driven by disruptions of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. β-catenin, a transcription factor, is the final regulator in the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway, and desmoids frequently display nuclear staining of β-catenin (Ng, et al. 2005). In 85% of patients, the desmoid bears an activating mutation in the β-catenin gene, CTNNB1. Several activating mutations of CTNNB1 are known, all of them in exon 3 (Huss, et al. 2013). In a small minority of patients, desmoids result from germline or sporadic loss of APC (Alman, et al. 1997b; Li, et al. 1998; Tejpar, et al. 1999). Because APC is a negative regulator of β-catenin stability, loss of APC leads to activation of β-catenin.

Because of the presence of CTNNB1 or APC mutations, Wnt/β-catenin activation is thought to represent the central oncogenic event in most cases of desmoid-type fibromatosis. However, approximately 15% of desmoids lack known APC or CTNNB1 disruption, so it is unclear what drives the formation of these so-called wild-type lesions (Tejpar, et al. 1999; Salas, et al. 2010). Recent reports suggest that patients with ‘wild-type’ desmoids have better outcomes than patients whose tumor harbors a defined mutation in CTNNB1 (T41A, S45F, or S45P), but this report has not been universally validated (Lazar, et al. 2008; Colombo, et al. 2013; Mullen, et al. 2013).

In this study, we performed a genomic characterization of ‘wild-type’ desmoids to identify genetic drivers of tumorigenesis. We also compared the ‘wild-type’ desmoids with CTNNB1-mutant desmoids to assess heterogeneity in clinicopathologic characteristics between the

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Tissue Procurement, Immunohistochemistry, and Nucleic Acid Preparation

Tumor and adjacent normal fat or muscle tissue samples were collected from 117 individual patients after surgical resection of desmoid-type fibromatosis between 2002 and 2013. Clinicopathologic characteristics describing patients and tumors, therapeutic interventions, follow-up dates, and disease status were recorded in a prospectively maintained database. Patients with a recorded history of familial adenomatous polyposis were excluded from this analysis. All patients provided informed consent per a protocol (#02-060) that was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Samples were snap-frozen and cryomolds prepared. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)—stained slides from each cryomold were reviewed by a sarcoma-specific pathologist (M.H.) and regions of normal tissue removed by macrodissection. This procedure allowed all analyses to be performed on samples composed of >90% tumor. DNA and RNA were prepared using RNeasy and DNeasy Mini Kits (QIAGEN).

Gene Expression Array Preparation and Analysis

cDNA was synthesized in the presence of oligo(dT)24-T7 from Genset, and cRNA prepared using biotinylated CTP and UTP. cRNA was hybridized to HG U133A 2.0 mRNA expression arrays (Affymetrix). Results from these arrays were processed using the standard R/Bioconductor packages: gcRMA (based on Robust Multi-Array Average method) for quantitation and normalization and LIMMA empirical Bayes method for differential expression (Irizarry, et al. 2003; Smyth 2004). Unsupervised clustering was based on the 223 genes most variably expressed between each pairwise comparison; it was performed using the R function ‘dendrogram’ on one dimension.

Sequencing

Bidirectional Sanger sequencing was performed as previously reported (Pratilas, et al. 2008; Janakiraman, et al. 2010). Briefly, CTNNB1 exon 3 was amplified by PCR using primers with sequences GTAAAACGACGGCCAGTTCACTGAGCTAACCCTGGCT and CAGGAAACAGCTATGACCTCCACAGTTCAGCATTTACCT and HotStart Taq (Kapa Biosystems). Templates were purified (AMPure, Agencourt Biosciences) and sequenced bidirectionally with Big Dye Terminator Kit v. 3.1 (Applied Biosystems). After removal of dye terminators (CleanSEQ, Agencourt Biosciences), reactions were run on ABI PRISM 3730xl sequencing apparatus (Applied Biosystems). Reads were assembled against the reference sequence using Consed 16.0 (Gordon, et al. 1998). Mutations were called by Polyphred 6.02b and Polyscan 3.0 and annotated with Genomic Mutation Consequence Calculator (Nickerson, et al. 1997; Chen, et al. 2007; Major 2007).

Whole-exome sequencing and data analysis were performed as previously described (Chmielecki, et al. 2013). Briefly, DNA (100 ng) from tumor and a normal muscle or fat sample from each patient was sheared. After end repair, samples were phosphorylated and ligated to barcoded sequence adaptors. Fragments between 200 and 350 bp underwent exonic hybrid capture with SureSelect v2 Exome bait (Agilent), then captured fragments were sequenced on Illumina HiSeq flowcells. The Firehose pipeline was used to manage input and output files, and MuTect and MutSig algorithms were used to identify statistically significant somatic mutations. The CapSeg (Copy number from exome sequencing) was used to identify copy number alterations and dRanger to identify somatic fusions (Chmielecki, et al. 2013; Cibulskis, et al. 2013; Lawrence, et al. 2013).

454 and MiSeq Validation of Gene Mutations

For 454 sequencing, genomic DNA extracted from tumor (DES1002) and normal control tissue from the same patient was used for PCR using primers with 454 tails (CGTATCGCCTCCCTCGCGCCATCAGTCTCAGGATATGAATTAGCTTATTTAGTTG and CTATGCGCCTTGCCAGCCCGCTCAGTACCCTCCACAAAGCACACACATATTAGTT). For MiSeq sequencing, biotinylated probes covering CTNNB1 exon 3 were used to prepare samples. In both cases, PCR was performed using the KAPA HiFi HotStart DNA polymerase.

In 454 sequencing, libraries were hybridized to the 454FLX platform. Between 1500 and 2000 reads per amplicon were generated using a 454 FLX platform (Roche). Alignment and variant detection was alternatively carried out both with ssahaSNP (Sanger Institute) and with a pipeline that combined BWA alignment, Picard tools, and VarScan (Koboldt, et al. 2009) variant detection.

In MiSeq sequencing, libraries were hybridized to the Illumina MiSeq platform (IDT Xgen lockdown protocol). Results were analyzed using BWA alignment and the Haplotype mutation caller (GATK) (Ho, et al. 2013).

Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (CGH) and Molecular Cytology

Genomic DNA was analyzed with Agilent 1M oligonucleotide arrays according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A DNA reference set [Human genomic DNA from blood (buffy coat); Roche Applied Science] was applied in conjunction with DNA prepared from tumor to allow for competitive hybridization. Array CGH data were processed using a normalization method that corrects for GC artifacts and then segmented using the standard CBS segmentation algorithm. Gene-level copy number calls were determined using the R-package algorithm Copynumber (Nilsen, et al. 2012).

Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed with a 3-color probe comprising centromeric repeat plasmids for chromosomes 6, 7, and 17. Tissue sections were de-waxed and hybridized according to standard procedures. FISH signals were scored for a minimum of 100 nuclei.

Statistical Analysis

Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical characteristics were compared across subgroups of desmoids defined according to underlying mutation using Fisher’s exact test analysis on all samples. Univariate analysis of recurrence-free survival stratified based on mutation status was performed for patients undergoing R0 or R1 resection using Kaplan-Meier analysis and log rank test; the corresponding multivariate analysis was performed using Cox regression analysis.

RESULTS

Sanger Sequencing of CTNNB1 in Desmoid-type Fibromatosis

Sanger sequencing of CTNNB1 exon 3 was performed on sporadic desmoids resected from 117 individual patients (Tables S1, S2). CTNNB1 T41A (n=55; 46%), S45F (n=35; 29%), and S45P (n=8; 6.7%) mutations were identified in 98 patients (82%), a proportion similar to that in previous reports. Two patients had deletions in exon 3 of CTNNB1 (H36del and A39-G48del) and another had a deletion (A39del) as well as T41A and T40A mutations; based on the structure of β-catenin, all these mutations are expected to be activating. The remaining 16 patients (13%) had no discernible mutation in CTNNB1 exon 3 as assessed by Sanger sequencing (‘wild-type’ tumors; Figure S1).

Clinicopathologic Comparison of ‘Wild-type’ and Mutated Desmoids

Patients with ‘wild-type’ tumors were similar to subsets of patients with each defined CTNNB1 mutation (i.e., T41A, S45F, S45P, or deletion) in terms of age, gender, tumor size, and primary vs recurrent presentation status (all p>0.1; Table S1). Mutation was, however, highly correlated with tumor site (p=0.006). Tumors with S45F mutation were most often localized to the extremity (57%), T41A-associated tumors to the abdominal cavity (44%), and ‘wild-type’ tumors to the abdominal wall (38%).

Immunohistochemistry was used to examine β-catenin in 40 desmoids. Twenty-one (52%) had nuclear β-catenin staining (Figure S2). Nuclear staining was positive in 4 of 8 (50%) ‘wild-type’ tumors and in 17 of 32 tumors (53%) with known CTNNB1 mutation (4 of 11 with S45 mutation, 12 of 18 with T41A mutation, 1 of 2 with S45P mutation, and not in the tumor with H36del). Frequency of nuclear staining did not differ significantly between subgroups of tumors with each unique mutation (p=0.44) or between ‘wild-type’ tumors and those with all defined mutations (0.874), suggesting that β-catenin signaling is dysregulated in both mutated and ‘wild-type’ tumors.

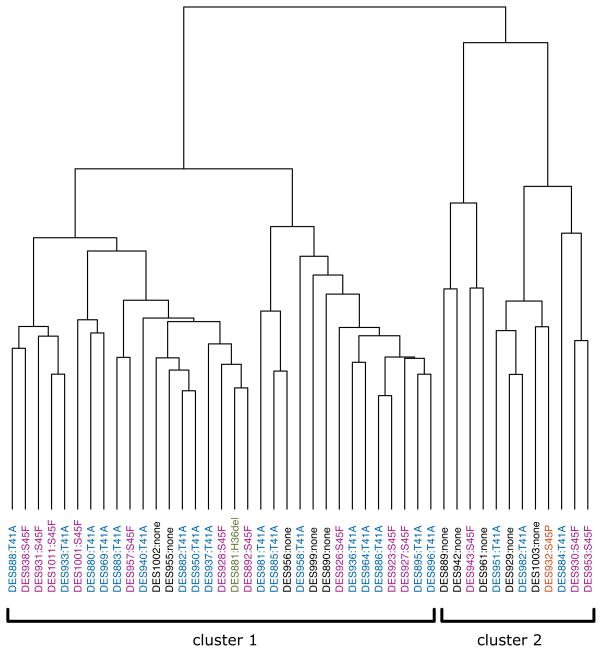

Similar to results observed in clinicopathologic analyses, gene expression profiles did not clearly define differences between the CTNNB1 mutant and ‘wild-type’ desmoid-type fibromatosis. RNA isolated from 45 tumors and 16 normal mesenchymal tissue samples (8 fat and 8 muscle) was analyzed using U133A 2.0 expression arrays. Unsupervised clustering demonstrated that all the desmoids clustered separately from normal tissue (Figure S3), but ‘wild-type’ tumors did not cluster separately from CTNNB1 mutant tumors. Similarly, unsupervised clustering of the tumors alone did not separate the two tumor subsets (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Unsupervised clustering of desmoid-type fibromatoses based on the 1% of genes whose expression was most variable between tumors. ‘Wild-type’ tumors are indicated with black text; tumors with CTNNB1 detected by Sanger sequencing are indicated with colored text.

Finally, patient outcomes were analyzed in tumors designated ‘wild-type’ based on Sanger sequencing and those with Sanger-identified CTNNB1 mutations. Median follow-up (from the time of initial resection at Memorial Sloan Kettering) was 40 months. No significant differences in local recurrence rates were observed between patients with T41A, S45F, or S45P CTNNB1 mutations as compared to those with none of these three mutations identified by Sanger sequencing (Figure S4A). Patients with ‘wild-type’ tumors tended to have longer recurrence-free survival than those with S45F mutant tumors during early follow-up, but this association was not clearly sustained at later time points and did not reach significance in univariate analysis (p=0.17). In a multivariate analysis that included mutation status and tumor site, the association between mutation status and recurrence-free survival was clearly non-significant (p>0.4), whereas tumor site was strongly associated with recurrence-free survival (multivariate hazard ratio 3.56 for extremity vs non-extremity; p=0.013) (Table 1). We also analyzed the subset of 80 patients who underwent resection for primary desmoids (Figure S4B; Table 1), and the results were nearly identical to those for the entire cohort. In particular, there continued to be no significant difference in recurrence-free survival for patients with T41A or S45F mutation compared to those with ‘wild-type’ tumors as defined by Sanger sequencing.

Table 1.

Analyses of factors prognostic for local recurrence in desmoid-type fibromatoses.

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Hazard ratio | p | Hazard ratio | p | |

| All patients | ||||

| Mutation (vs. none)* | ||||

| T41A | 0.76 | 0.64 | 0.92 | 0.89 |

| S45F | 2.15 | 0.17 | 1.59 | 0.41 |

| Site (vs. non-extremity) | ||||

| Extremity | 3.56 | <0.001 | 2.79 | 0.013 |

|

| ||||

| Patients with primary tumors only | ||||

| Mutation (vs. none)* | ||||

| T41A | 0.76 | 0.65 | – | – |

| S45F | 2.15 | 0.17 | – | – |

mutation status as defined by Sanger sequencing

Whole-exome Sequencing of Desmoid-type Fibromatosis

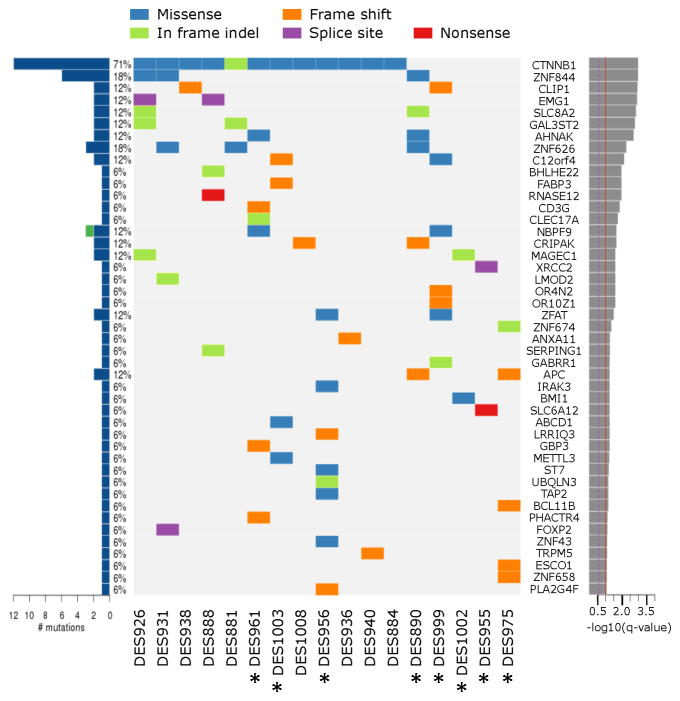

To further characterize the genomic events underlying initiation in ‘wild-type’ desmoids, whole-exome sequencing was performed on DNA from eight of the ‘wild-‘type’ tumors, eight of the tumors with CTNNB1 point mutations, and one tumor with H36del mutation. On average 29 Mb was sequenced for each tumor, and 87% of exons were captured at a depth of 88x or greater. The number of non-synonymous mutations detected per tumor ranged from 4 to 29, with less than one mutation detected per Mb (Figure S5, Table S3). This corresponded to 249 somatically mutated genes, with 45 reaching statistical significance as determined by the MutSig algorithm (q<0.1; Figure 2) (Lawrence, et al. 2013).

Figure 2.

Somatically mutated genes in desmoid tumors reaching statistical significance. Desmoids designated ‘wild-type’ by Sanger sequencing are annotated (*). The bar chart at the left shows the number of mutations found and the percentage of tumors affected; blue indicates non-silent mutations and green denotes the one silent mutation found in these genes (in NBPF9). For ZNF844, six mutations were found in three tumors. The center panel shows the types of non-silent mutations in each tumor. The bar graph at right shows the statistical significance of each mutated gene (derived from MutSig), with the red line indicating the threshold for significance (q<0.1).

Surprisingly, the whole-exome sequencing detected mutations in CTNNB1 in three of the eight ‘wild-type’ samples. In each case, the mutation was present at a low mutant allele frequency (10%, 10%, and 21%), presumably below the limit of detection for Sanger sequencing. In two other tumors, somatic mutations in the APC gene were identified. Thus, five of the eight ‘wild-type’ desmoids (62%) had CTNNB1 or APC mutation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Whole-exome sequencing of desmoids

| Sample | CTNNB1 mutation By Sanger | Whole-exome sequencing results (allele frequency)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTNNB1 mutation | APC mutation | Other event noted | ||

| DES1008 | S45F | S45F (32%) | None | |

| DES931 | S45F | S45F (32%) | None | |

| DES938 | S45F | S45F (46%) | None | |

| DES926 | S45F | S45F (38%) | None | |

| DES884 | T41A | T41A (36%) | None | |

| DES888 | T41A | T41A (33%) | None | |

| DES936 | T41A | T41A (22%) | None | |

| DES940 | T41A | T41A (54%) | None | |

| DES881 | H36del | H36del (30%) | None | |

|

| ||||

| DES1003 | None | T41A (10%) | None | |

| DES956 | None | T41A (21%) | None | |

| DES961 | None | T41A (10%) | None | |

| DES890 | None | None | I1918fs (61%) | APC loss |

| DES975 | None | None | K1462fs (70%) | APC loss |

| DES955 | None | None | None | Chr 6 loss |

| DES999 | None | None | None | Chr 6 loss |

| DES1002 | None | None | None | BMI1 Q59E (8%) |

Of the three remaining ‘wild-type’ tumors analyzed by whole-exome sequencing, two had no somatic mutations that can be clearly linked to regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, but one had a missense mutation affecting the BMI1 gene (Q59E; 8.8% of reads). BMI1 activates Wnt signaling by downregulation of the DKK family of proteins (Cho, et al. 2013). The mutation in BMI1 was confirmed by 454 sequencing (3% of reads in tumor, but absent in normal blood from the same patient).

Copy Number Alterations in ‘Wild-type’ Desmoid-type Fibromatosis

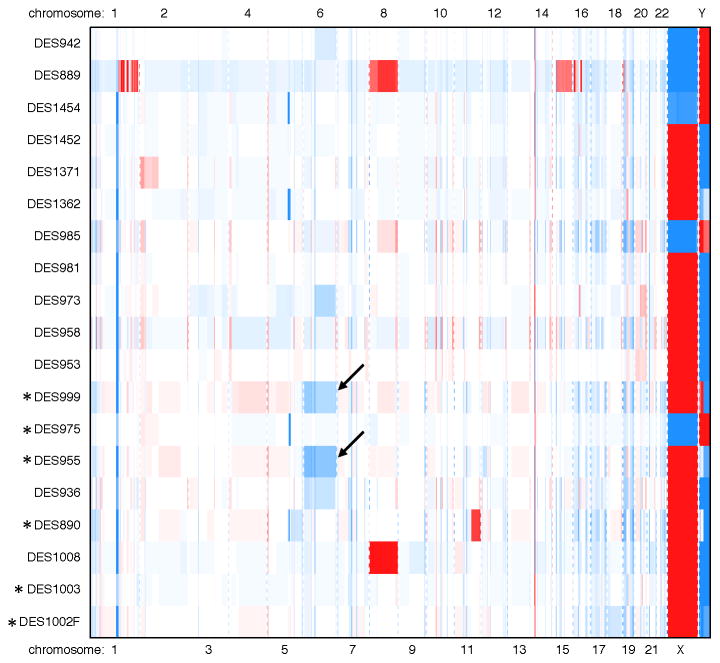

Whole-exome data on ‘wild-type’ and CTNNB1 desmoids were analyzed to identify potential fusion proteins and copy number alterations that may affect tumorigenesis. No recurrent fusions were identified (Table S4), but a few recurrent copy number alterations were identified (Figure S6). In both of the wild-type tumors with identified mutation in APC, we also detected copy number loss in a stretch of chromosome 5 that encompasses APC, suggesting a ‘second hit’ contributing to desmoid initiation. In the two tumors with no definable mutation in genes regulating Wnt signaling (CTNNB1, APC, or BMI1), the analysis demonstrated chromosome 6 loss, an event previously associated with medulloblastomas with activated Wnt signaling cascades. This finding was supported by both array CGH (Figure 3) and FISH analysis with probe directed to the centromere of chromosome 6, with chromosome 7 and 17 centromere probes as controls (Figure S7). In the tumor DES999, 89% of nuclei had 0 or 1 signals detected for chromosome 6, compared to 69% for chromosome 7 and 77% for chromosome 17. In the other tumor, DES955, the percentages of nuclei with 0–1 signals detected were 81%, 62%, and 61% for chromosomes 6, 7, and 17, respectively.

Figure 3.

Copy number alterations in desmoid tumors as identified from array CGH results by the R-package algorithm copynumber. Desmoids designated ‘wild-type’ by Sanger sequencing are annotated (*). Blue indicates copy number loss and red indicates gain. Chromosome 6 loss was found in two tumors with no identifiable abnormality in CTNNB1 or APC (DES955, DES999; see arrows) as well as in two tumors with CTNNB1 mutation.

Directed Genomic Analysis of Additional ‘Wild-type’ Desmoids

In light of the whole-exome results described above, we sequenced CTNNB1 exon 3 using the MiSeq platform in eight additional ‘wild-type’ desmoid samples (i.e., the desmoids identified as ‘wild-type’ in our initial Sanger sequencing that were not analyzed by whole-exome sequencing). Average coverage of exon 3 in the region of common CTNNB1 mutations was greater that 2300x. Consistent with our whole-exome analysis, four of the eight tumors had CTNNB1 mutations: three T41A (6%, 16%, and 33% of reads) and one A39V (1% of reads). Of note, repeat Sanger sequencing performed on the sample with 33% mutated reads again failed to identify the mutation by this traditional method (Figure S8).

The four remaining samples were analyzed by array CGH to look for loss of APC or deletion of chromosome 6. One of these samples had loss of APC. Therefore, five of this set of eight ‘wild-type’ samples had genomic events affecting CTNNB1 or APC. Taken together with whole-exome sequencing and MiSeq data, this result demonstrates that ten of 16 ‘wild-type’ samples in the study cohort and 111 of 117 total samples (95%) had CTNNB1 mutation, APC mutation, and/or APC loss. In general, those tumors with CTNNB1 mutation detected by whole exome sequencing or MiSeq had lower mutant allele frequencies than did those tumors with mutation detected by Sanger sequencing.

Having refined our knowledge of which tumors were CTNNB1 mutant and which wild type, we re-analyzed the associations of CTNNB1 mutation status, now defined by next-generation sequencing platforms, with tumor site and with patient outcome. Mutation status persisted in being highly correlated with site (p=0.0015). Though only one patient with true wild-type genotype (defined by whole exome or MiSeq analysis) had a recurrence, CTNNB1 wild-type genotype was not clearly associated with improved recurrence-free survival even on univariate analysis (hazard ratio 0.31 and p=0.26 for wild-type vs S45F mutation; hazard ratio 0.77 and p=0.80 for wild-type vs T41A mutation). This may reflect the rarity of the wild-type genotype and the consequent limited power of this analysis. In fact, it may not be feasible to characterize true ‘wild-type’ lesions as defined by next-generation sequencing since these tumors may be driven by a range of extremely rare genomic events.

DISCUSSION

Although disruptions of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway are believed to underlie pathogenesis of most desmoids, in multiple studies approximately 15% of desmoids have shown no aberrations in CTNNB1 or APC (Alman, et al. 1997b; Salas, et al. 2010). To determine what molecular events underlie pathogenesis in these ‘wild-type’ desmoids, we undertook a genomic analysis of 117 desmoids, with in-depth, multiplatform analysis being performed on 16 with no mutation in CTNNB1 as assessed by Sanger sequencing. Our gene expression and clinicopathologic results were consistent with the idea of a common oncogenic pathway in CTNNB1 mutant and ‘wild-type’ desmoids as assessed by Sanger sequencing. When gene expression profiles were examined, the ‘wild-type’ tumors did not cluster separately from other desmoids, ‘wild-type’ lesions did not have a different clinical behavior from tumors with either a CTNNB1 mutation, and a substantial number of ‘wild-type’ tumors stained for nuclear β-catenin, as do tumors with classic mutations in the Wnt pathway components. Of note, rates of IHC positivity were lower than those commonly reported in the literature, potentially because staining was done on a tissue microarray, and the small samples combined with heterogeneous staining observed for β-catenin may affect sensitivity of the stain.

APC loss, previously observed in sporadic desmoids, was identified in three of these ‘wild-type’ desmoids (Alman, et al. 1997b). Surprisingly, however, deep sequencing clearly demonstrated that CTNNB1 mutation was present in seven of the ‘wild-type’ tumors, albeit generally at lower frequency than in the tumors in which a CTNNB1 mutation was detected by traditional Sanger sequencing. One mutation, A39V, has not commonly been observed in desmoids. These results demonstrate that a larger proportion of desmoids than previously recognized have an activating CTNNB1 exon 3 mutation or APC loss (95% in this study as compared to ~85% in previous reports). This finding has important implications for attempts to use mutation status to predict patient outcomes. A subset of recent studies has suggested that desmoids without mutations in CTNNB1 have lower local recurrence rates than those with detectable mutation (Lazar, et al. 2008; Colombo, et al. 2013) though this has not been universally observed (Mullen, et al. 2013). Our study suggests that standard laboratory testing may not be accurate in defining ‘wild-type’ mutation status, and difference in methodologies used to detect mutations may also underlie variation between studies on the prognostic significance of ‘wild-type’ designation.

It should be noted that many of the desmoids we analyzed by next-generation sequencing, despite being prepared from cryomolds that were dissected to remove contaminating tissues, had CTNNB1 mutation in only a small number of reads (e.g., 6%). This suggests a significant amount of intratumoral heterogeneity, which could represent infiltration of the tumors by normal stromal or immune cells. Given the relatively homogeneous histologic appearance of desmoid-type fibromatosis, however, and the fact that not all tumor cells within a section stain for β-catenin, it is also possible that our findings represent mosaicism within at least some desmoids. Similar findings have been observed in subsets of endochondromas and spindle cell hemangiomas (IDH1 mutations) and osteochondroma (EXT1 and EXT2 mutations) (Bovee 2010; Pansuriya, et al. 2011). Some of the tumors with infrequent mutations detected by whole-exome sequencing or MiSeq showed significant heterogeneity in nuclear β-catenin, but this was also observed in many of the samples with mutations detected by Sanger sequencing (data not shown), so it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions from these data.

Wnt signaling in neoplasms can be affected by mutations other than the canonical abnormalities in CTNNB1 and APC (e.g., AXIN2 and RNF43 mutations) (Liu, et al. 2000; Giannakis, et al. 2014). Although we detected no genomic changes in AXIN2 or RNF43, we did detect other aberrations that could disrupt Wnt/β-catenin signaling in three of the six ‘wild-type’ tumors without CTNNB1 mutation or APC loss. One tumor had mutation of BMI1 (a regulator of the DKK family of Wnt inhibitors), and two had loss of chromosome 6, an event exclusively associated with subsets of medulloblastoma with known Wnt activation (Clifford, et al. 2006; Cho, et al. 2013). Thus, among 117 desmoids, only three were not shown to have genetic aberrations hypothesized to affect Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Because these three tumors had not undergone whole-exome sequencing, it remains possible that they had mutations in APC, BMI1, or other regulators of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

Systemic therapies have been of little efficacy in patients with desmoid-type fibromatosis, and those, such as sorafenib and adriamycin, that can effect responses do so by unclear mechanisms. Although we lack clinically effective Wnt and β-catenin inhibitors, given the near universal finding genomic events altering Wnt/β-catenin signaling molecules, it is obvious that future studies should seek to understand the signaling aberrations induced by the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in desmoid-type fibromatosis. This may allow us to develop predictive markers for response to treatments already in clinical use or to develop novel therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Clinical characteristics and CTNNB1 mutations of sporadic desmoid-type fibromatoses.

Figure S1. Representative Sanger sequencing chromatographs of wild-type CTNNB1 and common CTNNB1 exon 3 mutations found in desmoid-type fibromatoses.

Figure S2. Representative immunohistochemical staining of desmoids, showing samples that stained negative and positive (both heterogeneous and diffuse) for nuclear β-catenin.

Figure S3. Unsupervised clustering of desmoid and normal tissues based on the 1% of genes whose expression was most variable between samples.

Figure S4. Local recurrence–free survival in the entire cohort (A) and in primary tumors (B) after resection of desmoids, stratified by CTNNB1 mutation status as determined by Sanger sequencing. The group labeled “no missense mutation” does not include tumors with deletion mutations in CTNNB1.

Figure S5. Number of mutations (A), Mb sequenced (B), and mutations per Mb (C) calculated for each tumor specimen analyzed by whole-exome sequencing. dbSNP mutations represent those catalogued in the National Institute for Biotechnology Information dbSNP database and likely represent normal human variants.

Figure S6. Copy number alterations in desmoids as identified from whole-exome sequencing by the CapSeg algorithm. Blue indicates copy number loss and red indicates gain. APC loss was identified in two tumors with APC mutation, and chromosome 6 loss was identified in two tumors with no identifiable abnormality in CTNNB1 or APC.

Figure S7. Results of FISH staining for chromosome 6, with chromosomes 7 and 17 as controls. (A) A representative figure demonstrating CEP6 (pink) and CEP7 (green) staining in a section of DES999. (B) Graphs show number of FISH signals per nucleus in two ‘wild-type’ desmoids, DES999 and DES955, quantitated for a minimum of 100 nuclei.

Figure S8. Chromatograph from Sanger sequencing for the desmoid found to be ‘wild-type’ by this traditional sequencing method but having a CTNNB1 exon 3 mutation (T41A) in 33% of reads by MiSeq.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Margaret Leversha for assistance with cytogenetic studies, Agnes Viale, Christophe Lemetre, and Kety Huberman for aid with directed exon sequencing, Janet Novak for editorial assistance, and Heidi Trenholm and Christina Curtin for database support. This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute through the SPORE in Soft Tissue Sarcoma grant P50-CA140146 (S.S, L.-X.Q., A.M.C., N.D.S, M.H.) and the MSKCC Institutional Cancer Center Core Grant P30-CA008748. A portion of this work was conducted as part of the Slim Initiative for Genomic Medicine, a project of the Carlos Slim Foundation in Mexico. J.C. was supported by an American Cancer Society AstraZeneca postdoctoral Fellowship. A.M.C. is supported by the Kristen Ann Carr Foundation, Alicia and Corey Pinkston, Cycle for Survival and a Mentored Research Scholar Grant in Applied and Clinical Research MRSG-15-064-01-TBG from the American Cancer Society.

References

- Alman BA, Pajerski ME, Diaz-Cano S, Corboy K, Wolfe HJ. Aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumor) is a monoclonal disorder. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1997a;6:98–101. doi: 10.1097/00019606-199704000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alman BA, Li C, Pajerski ME, Diaz-Cano S, Wolfe HJ. Increased beta-catenin protein and somatic APC mutations in sporadic aggressive fibromatoses (desmoid tumors) Am J Pathol. 1997b;151:329–334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovee JV. EXTra hit for mouse osteochondroma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1813–1814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914431107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, McLellan MD, Ding L, Wendl MC, Kasai Y, Wilson RK, Mardis ER. PolyScan: an automatic indel and SNP detection approach to the analysis of human resequencing data. Genome Res. 2007;17:659–666. doi: 10.1101/gr.6151507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielecki J, Crago AM, Rosenberg M, O’Connor R, Walker SR, Ambrogio L, Auclair D, McKenna A, Heinrich MC, Frank DA, Meyerson M. Whole-exome sequencing identifies a recurrent NAB2-STAT6 fusion in solitary fibrous tumors. Nat Genet. 2013;45:131–132. doi: 10.1038/ng.2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JH, Dimri M, Dimri GP. A positive feedback loop regulates the expression of polycomb group protein BMI1 via WNT signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:3406–3418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.422931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, Sivachenko A, Jaffe D, Sougnez C, Gabriel S, Meyerson M, Lander ES, Getz G. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford SC, Lusher ME, Lindsey JC, Langdon JA, Gilbertson RJ, Straughton D, Ellison DW. Wnt/Wingless pathway activation and chromosome 6 loss characterize a distinct molecular subgroup of medulloblastomas associated with a favorable prognosis. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2666–2670. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.22.3446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo C, Miceli R, Lazar AJ, Perrone F, Pollock RE, Le Cesne A, Hartgrink HH, Cleton-Jansen AM, Domont J, Bovee JV, Bonvalot S, Lev D, Gronchi A. CTNNB1 45F mutation is a molecular prognosticator of increased postoperative primary desmoid tumor recurrence: An independent, multicenter validation study. Cancer. 2013;119:3696–3702. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easter DW, Halasz NA. Recent trends in the management of desmoid tumors. Summary of 19 cases and review of the literature. Ann Surg. 1989;210:765–769. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198912000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannakis M, Hodis E, Jasmine Mu X, Yamauchi M, Rosenbluh J, Cibulskis K, Saksena G, Lawrence MS, Qian ZR, Nishihara R, Van Allen EM, Hahn WC, Gabriel SB, Lander ES, Getz G, Ogino S, Fuchs CS, Garraway LA. RNF43 is frequently mutated in colorectal and endometrial cancers. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1264–1266. doi: 10.1038/ng.3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D, Abajian C, Green P. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 1998;8:195–202. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higaki S, Tateishi A, Ohno T, Abe S, Ogawa K, Iijima T, Kojima T. Surgical treatment of extra-abdominal desmoid tumours (aggressive fibromatoses) Int Orthop. 1995;19:383–389. doi: 10.1007/BF00178355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho AS, Kannan K, Roy DM, Morris LG, Ganly I, Katabi N, Ramaswami D, Walsh LA, Eng S, Huse JT, Zhang J, Dolgalev I, Huberman K, Heguy A, Viale A, Drobnjak M, Leversha MA, Rice CE, Singh B, Iyer NG, Leemans CR, Bloemena E, Ferris RL, Seethala RR, Gross BE, Liang Y, Sinha R, Peng L, Raphael BJ, Turcan S, Gong Y, Schultz N, Kim S, Chiosea S, Shah JP, Sander C, Lee W, Chan TA. The mutational landscape of adenoid cystic carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:791–798. doi: 10.1038/ng.2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huss S, Nehles J, Binot E, Wardelmann E, Mittler J, Kleine MA, Kunstlinger H, Hartmann W, Hohenberger P, Merkelbach-Bruse S, Buettner R, Schildhaus HU. beta-catenin (CTNNB1) mutations and clinicopathological features of mesenteric desmoid-type fibromatosis. Histopathology. 2013;62:294–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janakiraman M, Vakiani E, Zeng Z, Pratilas CA, Taylor BS, Chitale D, Halilovic E, Wilson M, Huberman K, Ricarte Filho JC, Persaud Y, Levine DA, Fagin JA, Jhanwar SC, Mariadason JM, Lash A, Ladanyi M, Saltz LB, Heguy A, Paty PB, Solit DB. Genomic and biological characterization of exon 4 KRAS mutations in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5901–5911. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koboldt DC, Chen K, Wylie T, Larson DE, McLellan MD, Mardis ER, Weinstock GM, Wilson RK, Ding L. VarScan: variant detection in massively parallel sequencing of individual and pooled samples. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2283–2285. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, Kryukov GV, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Carter SL, Stewart C, Mermel CH, Roberts SA, Kiezun A, Hammerman PS, McKenna A, Drier Y, Zou L, Ramos AH, Pugh TJ, Stransky N, Helman E, Kim J, Sougnez C, Ambrogio L, Nickerson E, Shefler E, Cortes ML, Auclair D, Saksena G, Voet D, Noble M, DiCara D, Lin P, Lichtenstein L, Heiman DI, Fennell T, Imielinski M, Hernandez B, Hodis E, Baca S, Dulak AM, Lohr J, Landau DA, Wu CJ, Melendez-Zajgla J, Hidalgo-Miranda A, Koren A, McCarroll SA, Mora J, Lee RS, Crompton B, Onofrio R, Parkin M, Winckler W, Ardlie K, Gabriel SB, Roberts CW, Biegel JA, Stegmaier K, Bass AJ, Garraway LA, Meyerson M, Golub TR, Gordenin DA, Sunyaev S, Lander ES, Getz G. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013;499:214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar AJ, Tuvin D, Hajibashi S, Habeeb S, Bolshakov S, Mayordomo-Aranda E, Warneke CL, Lopez-Terrada D, Pollock RE, Lev D. Specific mutations in the beta-catenin gene (CTNNB1) correlate with local recurrence in sporadic desmoid tumors. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1518–1527. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JJ, Boland PJ, Leung DH, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. The enigma of desmoid tumors. Ann Surg. 1999;229:866–872. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199906000-00014. discussion 872–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Bapat B, Alman BA. Adenomatous polyposis coli gene mutation alters proliferation through its beta-catenin-regulatory function in aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumor) Am J Pathol. 1998;153:709–714. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65614-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Dong X, Mai M, Seelan RS, Taniguchi K, Krishnadath KK, Halling KC, Cunningham JM, Boardman LA, Qian C, Christensen E, Schmidt SS, Roche PC, Smith DI, Thibodeau SN. Mutations in AXIN2 cause colorectal cancer with defective mismatch repair by activating beta-catenin/TCF signalling. Nat Genet. 2000;26:146–147. doi: 10.1038/79859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez R, Kemalyan N, Moseley HS, Dennis D, Vetto RM. Problems in diagnosis and management of desmoid tumors. Am J Surg. 1990;159:450–453. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)81243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major JE. Genomic mutation consequence calculator. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:3091–3092. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markhede G, Lundgren L, Bjurstam N, Berlin O, Stener B. Extra-abdominal desmoid tumors. Acta Orthop Scand. 1986;57:1–7. doi: 10.3109/17453678608993204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant NB, Lewis JJ, Woodruff JM, Leung DH, Brennan MF. Extremity and trunk desmoid tumors: a multifactorial analysis of outcome. Cancer. 1999;86:2045–2052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen JT, Delaney TF, Rosenberg AE, Le L, Iafrate AJ, Kobayashi W, Szymonifka J, Yeap BY, Chen YL, Harmon DC, Choy E, Yoon SS, Raskin KA, Hornicek FJ, Nielsen GP. beta-Catenin Mutation Status and Outcomes in Sporadic Desmoid Tumors. Oncologist. 2013;18:1043–1049. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng TL, Gown AM, Barry TS, Cheang MC, Chan AK, Turbin DA, Hsu FD, West RB, Nielsen TO. Nuclear beta-catenin in mesenchymal tumors. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:68–74. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson DA, Tobe VO, Taylor SL. PolyPhred: automating the detection and genotyping of single nucleotide substitutions using fluorescence-based resequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2745–2751. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.14.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen G, Liestol K, Van Loo P, Moen Vollan HK, Eide MB, Rueda OM, Chin SF, Russell R, Baumbusch LO, Caldas C, Borresen-Dale AL, Lingjaerde OC. Copynumber: Efficient algorithms for single- and multi-track copy number segmentation. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:591. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pansuriya TC, van Eijk R, d’Adamo P, van Ruler MA, Kuijjer ML, Oosting J, Cleton-Jansen AM, van Oosterwijk JG, Verbeke SL, Meijer D, van Wezel T, Nord KH, Sangiorgi L, Toker B, Liegl-Atzwanger B, San-Julian M, Sciot R, Limaye N, Kindblom LG, Daugaard S, Godfraind C, Boon LM, Vikkula M, Kurek KC, Szuhai K, French PJ, Bovee JV. Somatic mosaic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are associated with enchondroma and spindle cell hemangioma in Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1256–1261. doi: 10.1038/ng.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratilas CA, Hanrahan AJ, Halilovic E, Persaud Y, Soh J, Chitale D, Shigematsu H, Yamamoto H, Sawai A, Janakiraman M, Taylor BS, Pao W, Toyooka S, Ladanyi M, Gazdar A, Rosen N, Solit DB. Genetic predictors of MEK dependence in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9375–9383. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas S, Chibon F, Noguchi T, Terrier P, Ranchere-Vince D, Lagarde P, Benard J, Forget S, Blanchard C, Domont J, Bonvalot S, Guillou L, Leroux A, Mechine-Neuville A, Schoffski P, Lae M, Collin F, Verola O, Carbonnelle A, Vescovo L, Bui B, Brouste V, Sobol H, Aurias A, Coindre JM. Molecular characterization by array comparative genomic hybridization and DNA sequencing of 194 desmoid tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:560–568. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3:Article3. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejpar S, Nollet F, Li C, Wunder JS, Michils G, dal Cin P, Van Cutsem E, Bapat B, van Roy F, Cassiman JJ, Alman BA. Predominance of beta-catenin mutations and beta-catenin dysregulation in sporadic aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumor) Oncogene. 1999;18:6615–6620. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Nik-Amini S, Nadesan P, Stanford WL, Alman BA. Aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumor) is derived from mesenchymal progenitor cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7690–7698. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Clinical characteristics and CTNNB1 mutations of sporadic desmoid-type fibromatoses.

Figure S1. Representative Sanger sequencing chromatographs of wild-type CTNNB1 and common CTNNB1 exon 3 mutations found in desmoid-type fibromatoses.

Figure S2. Representative immunohistochemical staining of desmoids, showing samples that stained negative and positive (both heterogeneous and diffuse) for nuclear β-catenin.

Figure S3. Unsupervised clustering of desmoid and normal tissues based on the 1% of genes whose expression was most variable between samples.

Figure S4. Local recurrence–free survival in the entire cohort (A) and in primary tumors (B) after resection of desmoids, stratified by CTNNB1 mutation status as determined by Sanger sequencing. The group labeled “no missense mutation” does not include tumors with deletion mutations in CTNNB1.

Figure S5. Number of mutations (A), Mb sequenced (B), and mutations per Mb (C) calculated for each tumor specimen analyzed by whole-exome sequencing. dbSNP mutations represent those catalogued in the National Institute for Biotechnology Information dbSNP database and likely represent normal human variants.

Figure S6. Copy number alterations in desmoids as identified from whole-exome sequencing by the CapSeg algorithm. Blue indicates copy number loss and red indicates gain. APC loss was identified in two tumors with APC mutation, and chromosome 6 loss was identified in two tumors with no identifiable abnormality in CTNNB1 or APC.

Figure S7. Results of FISH staining for chromosome 6, with chromosomes 7 and 17 as controls. (A) A representative figure demonstrating CEP6 (pink) and CEP7 (green) staining in a section of DES999. (B) Graphs show number of FISH signals per nucleus in two ‘wild-type’ desmoids, DES999 and DES955, quantitated for a minimum of 100 nuclei.

Figure S8. Chromatograph from Sanger sequencing for the desmoid found to be ‘wild-type’ by this traditional sequencing method but having a CTNNB1 exon 3 mutation (T41A) in 33% of reads by MiSeq.