Abstract

This paper reports on the 6-month follow-up outcomes of an effectiveness study testing a multiple family group (MFG) intervention for clinic-referred youth (aged 7–11) with disruptive behavior disorders (DBDs) and their families in socioeconomically disadvantaged families compared to services-as-usual (SAU) using a block comparison design. The settings were urban community-based outpatient mental health agencies. Clinic-based providers and family partner advocates facilitated the MFG intervention. Parent-report measures targeting child behavior, social skills, and impairment across functional domains (i.e., relationships with peers, parents, siblings, and academic progress) were assessed across four timepoints (baseline, mid-test, post-test, and 6-month follow-up) using mixed effects regression modeling. Compared to SAU participants, MFG participants reported significant improvement at 6-month follow-up in child behavior, impact of behavior on relationship with peers, and overall impairment/need for services. Findings indicate that MFG may provide longer-term benefits for youth with DBDs and their families in community-based settings. Implications within the context of a transforming healthcare system are discussed.

Keywords: Effectiveness trials, Service delivery, Child disruptive behavior disorders, Socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, Inner-city communities

Introduction

Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD) are prevalent and, oftentimes, chronic psychiatric disorders of childhood (American Psychiatric Association 2000). These disorders, collectively referred to as disruptive behavior disorders (DBDs), are disproportionately found in low-income communities with high proportions of racial and ethnic minorities (Tolan et al. 2000). Youth residing in such communities are often deeply affected by the convergence of stressors associated with urban living and socioeconomic disadvantage (e.g., community crime and violence, unstable housing, limited supportive resources). Further, long-term outcomes for inner-city, behaviorally challenged youth of color are often poor (Appleyard et al. 2005). Although publicly funded child mental health clinics provide services within inner-city communities, low-income minority families frequently experience significant challenges to initial and ongoing engagement (Gopalan et al. 2010). Thus, providing effective and engaging mental health services to treat DBDs in these communities is imperative.

Parent management training is a particularly efficacious approach to treat DBDs for preschool and school-age youth (Eyberg et al. 2008), resulting in a growing interest to gauge effectiveness of this type of intervention when embedded in routine practice settings. However, questions remain as to whether findings from efficacy studies on parent management training reflect an accurate estimate of the extent to which such treatments are effective in typical practice. A vast majority of studies evaluating youth mental health treatments have not examined factors that reflect the real-world context in which the interventions are to be embedded (Michelson et al. 2013; Weisz et al. 2013). Specifically, few treatment studies targeting DBDs in youth have included key parameters such as: treating clinic-referred youth, offering treatment in routine community-based clinical settings; and providing treatment by existing practicing clinicians in those settings (as opposed to clinicians hired solely for research purposes). As a result, substantial concerns exist as to whether parent management training interventions can be readily translated to low-resource, routine service settings serving high-risk youth and their families. This is the typical context for publicly funded outpatient child mental health clinics.

As a result, research findings are likely to generalize to everyday practice when study designs consider key parameters relevant to typical public mental health practice (Hoagwood et al. 2002; Weisz et al. 2013). These parameters include treating clinic-referred, school-aged youth with DBDs, providing treatment in routine community-based clinic settings, and utilizing clinic-based providers. The multiple family group (MFG) intervention to reduce youth DBDs (e.g., Chacko et al. in press; McKay et al. 2011, 2010, 2002, 1999, 1995; Stone et al. 1996) was developed within this framework. Designed for delivery in outpatient mental health clinics within socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, MFG attempts to address clinical, financial, and regulatory constraints of these settings. Using a common elements approach (Chorpita and Daleiden 2009), MFG incorporates a group therapy delivery method and treatment targets (e.g., parental discipline and monitoring; contingent rewards; family organization; family communication) from the empirical literature in key areas (i.e., parent management training; family therapy) for effective treatment of youth with DBDs. Sessions focus on core effective family processes for treatment of child behavioral difficulties (“4 Rs”: Rules; Responsibility; Relationships; Respectful communication), as well as those factors impacting mental health services engagement (“2 Ss”: Stress and Social support). MFG content and practice activities are delivered through a collaborative facilitation model with a family partner advocate and a clinician. This team approach is an emerging innovation in family support services delivery within child mental health treatment (Hoagwood et al. 2010). Family partners advocates (also known as family peer support partners) are parents who have successfully navigated through the mental health system with their own families and are now helping other families do the same by facilitating engagement and reducing barriers in services (Hoagwood et al. 2010). Furthermore, the MFG model accounts for the training and supervision constraints of routine community-based out-patient mental health clinics in mind. Training for MFG (i.e., approximately 5–6 h interspersed across 1–2 days) and supervision (weekly group supervision for approximately 60 min with each facilitator team), lends itself amenable for adoption within the constraints of existing clinic settings.

MFG utilizes evidence-based engagement strategies known to improve retention in mental health services among socioeconomically disadvantaged families, including active problem solving and phone reminders (McKay et al. 1996, 1998). To further increase efficiency of and engagement in treatment, MFG relies on a multiple family group format, where multiple generations within a family interact with other families in a group setting. Group-delivered services address significant limitations in service capacity within inner-city neighborhoods by serving multiple families simultaneously, and are effective in teaching specific parenting skills (Miller and Prinz 1990; O’Shea and Phelps 1985; Prinz and Jones 2003; Webster-Stratton 1990). For minority families, who have been known to avoid mental health services due to stigma and fears of being blamed for their children’s difficulties, groups which focus on sharing and support may be more acceptable than traditional mental health treatment (Alvidrez 1999; Barrio 2000; Boyd-Franklin 1995; McKay and Bannon 2004; Snowden 2001). The group format allows for validation of members’ strengths, normalization of family struggles and mental health difficulties, empowerment among members through mutual aid, as well as much-needed social support to low-income urban families who frequently suffer from social isolation and high stress (Kazdin 1995). Group delivered services further maximize change within families as feedback from peers can be more credible than suggestions offered by clinical facilitators (McKay et al. 1995). However, groups are generally underutilized in clinic settings. When groups are offered, they typically involve separating parents from target children as well as excluding siblings. In contrast, MFG is an alternative treatment modality that allows parents, children with DBDs, and their siblings to remain together in session. In this way, MFG can expand available care options within community mental health settings.

Prior small-scale and preliminary studies of MFG (McKay et al. 2002, 1999) conducted in low-income, inner-city community mental health clinics demonstrated that youth receiving MFG had significantly greater improvements in conduct problems, hyperactivity, impulsivity and learning problems, as well as greater retention in mental health services, as compared to those receiving services-as-usual (SAU). More recently, a large clinical effectiveness trial compared MFG to a SAU comparison group across five timepoints (baseline, mid-test, post-test, 6-month follow-up, 18-month follow-up) for the treatment of DBDs in youth and their families within outpatient mental health clinics in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities (McKay et al. 2011). Findings suggested that at immediate post-treatment, MFG resulted in significantly reduced child oppositional/defiant behavior symptoms and improved social skills compared to youth in the SAU condition. Moreover, attendance for MFG sessions was substantially higher than established rates within child mental health services in socio-economically disadvantaged communities (Chacko et al. in press).

The current study examines whether such findings are maintained at the 6-month follow-up assessment. Several recent effectiveness studies utilizing variations of parent management training approaches to treat DBDs in community settings document that treatment gains can be maintained on child disruptive behavior at 6 months (e.g., Behan et al. 2001; Costin and Chambers 2007; Gardner et al. 2006; Kling et al. 2010; Kjobli and Ogden 2013), 12 months (e.g., Axberg and Broberg 2012; Hagen et al. 2011) or longer (e.g., Gardner et al. 2006; Weisz et al. 2012) follow-up assessments. Studies that have evaluated social competence have also revealed maintenance of gains on these outcomes (e.g., Hagen et al. 2011; Kjobli and Ogden 2013). Consequently, in the current study, we hypothesize benefits associated with MFG found at post-treatment on disruptive behavior and social competence will be at least maintained at the 6-month follow-up assessment.

Method

Participants

This study has received Institutional Review Board approval. Between October 2006 and 2010, participants were recruited from 13 community-based outpatient mental health clinics in low-income communities throughout the New York City metropolitan area. Clinic staff identified children with serious behavior difficulties at intake, and informed their adult caregivers about the study. Interested families were referred to research staff. Legal guardians signed written consent forms and youth participants provided verbal assent. In order to participate in the study, youth had to be between the ages of 7–11 years-old, and meet criteria at screening for a diagnosis of ODD or CD (American Psychiatric Association 2000), as ascertained by research staff via screening using the DBDs Rating Scale (Pelham et al.1992). As previously described, (Chacko et al. in press; McKay et al. 2011), n = 320 youth and their families were enrolled. The vast majority of participants identified as Latino (53 %) or Black/African American (30 %). Seventy-nine percent of families reported living on <$30,000 per year, with 67 % reported as single-parent households. The majority of youth participants (68 %) were male.

Procedures

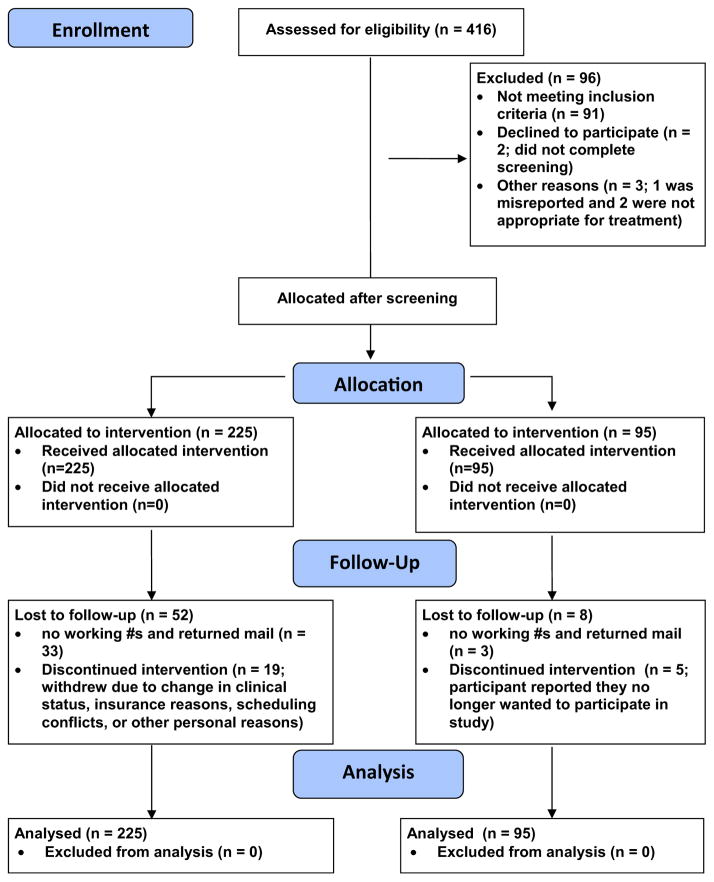

Study procedures have been previously described (McKay et al. 2011; Chacko et al. in press). Once the diagnosis of ODD or CD was confirmed, participants were assigned to the MFG experimental (n = 225) or clinical services as usual (SAU; n = 95) treatment conditions. Other caregivers and youth siblings were also enrolled. In order to ensure sufficient numbers of families were available to start MFG groups at participating clinics, condition assignment procedures were as follows. First, a set of participants (up to eight families) were recruited at each site and all were assigned to one of the two study conditions. Once the first set of families were assigned to the study condition, a second set of participants was assigned to the other study condition. Using a 2:1 allocation ratio, 6–8 eligible families were allocated to MFG, while 3–4 eligible families were assigned to SAU. This allocation ratio was utilized in order to ensure MFG groups could be populated as quickly and efficiently as possible. Importantly, decisions regarding condition assignment were not controlled by field staff consenting participants; rather, those decisions were made by project coordinators as to which of the two conditions was sequentially next to be filled. Finally, the use of unequal group ratios only significantly reduces the validity of a study when the ratio is 3:1 or more (Dumville et al. 2006). Consequently, the current study’s allocation ratio maximized study efficiency with little impact on statistical validity. This block comparison design is commonly used for health services trials with logistical constraints due to the need to deliver the intervention to groups of people at the same time (e.g., Goodwin et al. 2001). Attempts were made to minimize the potential influences of confounding variables on outcomes. Specifically, research staff and investigators were blind to youth and family profiles during allocation, and had no control regarding the order with which participants enrolled in study conditions. Figure 1 presents the CONSORT Diagram for this study.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT Diagram

At baseline, there were significantly greater percentage of married or cohabiting couples as primary caregivers (Chi square = 11.83, df = 5, p = 0.04) in the MFG group compared to the SAU group, where there were more grandparents (Chi square = 11.04, df = 4, p = 0.03) and single parents. On average, caregivers in the MFG group tended to be younger (t = −2.29, df = 308, p = 0.03). Post-hoc sensitivity analyses indicated that these baseline differences had no impact on the outcomes reported in this study, and as a result, were not included as covariates in analyses. The CONSORT diagram in Fig. 1 indicates the number of participants who dropped out by condition. The total number of participants who reported 6-month follow up data was n = 221. Analyses testing differential rates of attrition by condition indicated no differences between the experimental and control groups based on the number of participants responding at baseline, mid-test, and post-test assessment periods. At 6-month follow-up, a greater percentage of control group participants (79 %, n = 75) responded compared to participants in the experimental group (65 %, n = 146). This difference was significant (Chi square = 6.18, df = 1, p = 0.01). Analyses of demographic differences between responders and non-responders at 6-month follow-up indicated a significant association by response status and caregiver ethnicity (Chi square = 14.30, df = 5, p = 0.01). Seventy-seven percent of African-American caregivers, 68 % of Hispanic caregivers, and 100 % of Native American caregivers responded at 6-month follow-up, compared to only 50 % of Caucasian caregivers. However, among those participants who responded at the 6-month follow-up, there were no significant differences on baseline demographic variables by treatment condition.

Multiple Family Group (MFG)

MFG is a manualized intervention involving 6–8 families, composed of identified youth, their adult caregiver(s), and sibling(s) between the ages of 6 and 18. Weekly sessions take place over a 16-week period. Focusing on what the extant literature has identified as core effective family processes for treating child behavioral difficulties (“4 Rs”: Rules; Responsibility; Relationships; Respectful communication), as well as those factors impacting mental health services engagement (“2 Ss”:Stress and Social support), sessions (90–120 min long) also provided opportunities for exchanging information among families, practicing skills, and reviewing homework. The study was conducted in a state, similar to many other states with public child mental health systems, which employed family partner advocates and added family support services as an essential service offering (Hoagwood et al. 2010). Within the current study, family partner advocates had received initial base training provided by the state mental health authority. Competency was certified in a core set of areas, including engagement, system navigation, facilitation of groups, boundary setting, and self-care. Funding for these positions came from existing agency resources. However, many states across the US are increasingly allowing services provided by family partner advocates to be billable under typical insurance coverage (Hoagwood et al. 2010).

MFG groups were co-delivered by clinicians employed at each site and family partner advocates. Information on facilitator training, fidelity, and attendance has been previously reported in Chacko et al. (in press). MFG participants were not restricted from seeking additional services from the clinicsites or elsewhere. Although research staff provided support for clinics in incorporating the group model within their array of clinic services, it was ultimately clinic staff decision to determine how best to coordinate care across service types. For example, in some cases, MFG was a standalone treatment. In other instances, the MFG facilitators also saw families individually or referred to other types of care as needed. These decisions were based upon best clinical judgment of clinicians and clinic administrators. Table 1 summarizes additional services received at 6-month follow-up by treatment group. Please see Chacko et al. (in press) for more information on the MFG intervention.

Table 1.

Additional services received at 6-month follow-up by treatment group

| MFG (%) | SAU (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Individual child therapy | 26 | 26 |

| Outpatient family-based | 26 | 30 |

| Outpatient child group-based | 6 | 7 |

| Medication management | 28 | 24 |

| School-based | 6 | 5 |

| Case management | 4 | 3 |

| Crisis management | 2 | 2 |

| Inpatient/residential | 2 | 3 |

| Receiving no additional services | 52 | 30 |

| Receiving 1 additional service | 17 | 17 |

| Receiving 2 additional services | 23 | 22 |

| Receiving 3 additional services | 8 | 24 |

| Receiving 4 or more additional services | 0 | 7 |

MFG multiple family group, SAU services as usual

Services-As-Usual (SAU)

The SAU condition referred to any service offered by participating outpatient mental health clinic sites, including case management, individual therapy, family therapy, group therapy, and/or medication management. As with participants in the MFG group, SAU participants were also not restricted from seeking any available service at the participating outpatient mental health clinic (see Table 1).

Measures

IOWA Connors Rating Scale (IOWA CRS; Waschbusch and Willoughby 2008)

This, brief, widely used parent-report measure evaluates severity of inattentive-impulsive-overactive (IO) and oppositional-defiant (OD) behavior in children. This study focused on the five items measuring OD behaviors [not at all (0); just a little (1); pretty much (2); and very much (3)]. Items were summed to compute subscales (range 0–15). Higher scores indicate greater symptom severity. The current study utilized the OD subscale reported at baseline (α = 0.80), mid-test (α = 0.83), post-test (α = 0.86), and 6-month follow-up (α = 0.86). Cronbach’s α’s are reported for the current sample.

Social Skills Rating System: Social Skills Subscale (SSRS-SSS; Gresham and Elliott 1990)

Caregivers rated the importance and frequency of youth social skills (e.g., youth cooperation, assertion, responsibility, empathy, self-control) using a 3-point likert rating scale [0 (“never”) to 2 (“often”)], with higher scores signifying greater frequency of prosocial skills. Total score is computed by summing all 38 items (range 0–76). Cronbach’s α’s for the current sample at baseline, posttest, and 6-month follow-up assessments for SSRS-SSS were 0.88, 0.91 and 0.92, respectively.

Impairment Rating Scale (IRS; Fabiano et al. 2006)

Caregivers rate the severity of the impact of their children’s difficulties across functional domains on this 6-item rating scale (i.e., relationship with playmates or peers, relationship with the parent[s], relationship with sibling[s], academic progress, family functioning, self-esteem, overall need). The visual analogue scale ranges from 0 (“Not a problem at all. Definitely does not need treatment or special services”) to 6 (“Extreme problem; Definitely needs treatment and special services”), with higher scores indicating greater impairment. For the current study, we utilized the individual IRS items as separate, individual outcomes in the analyses, measured at baseline, post-test, and 6-month follow-up.

Data Analysis

In order to compare the effect of the two treatment conditions at the 6-month follow-up assessment, an intention to treat (ITT) analysis strategy was used. We conducted mixed effects regression (also known as multilevel linear modeling) with SuperMix software (Hedeker et al. 2008). With these analyses, parameters (intercepts and slopes) for measurements over time within cases are allowed to vary between cases while also accounting for correlations between measurements within cases. Mixed effects regression modeling is appropriate for modeling longitudinal change where there is attrition over time, with the assumption that data is at least missing at random (MAR) (e.g., ignorable). The MAR assumption was confirmed as reasonable through preliminary exploratory and sensitivity analyses conducted with the data (e.g., examining differences on baseline demographic variables between those with missing data and those with complete data). Mixed effects regression modeling permits different times and numbers of measurements within cases by using all available information to make estimates at each time point, accommodating for partially missing data. Consequently, analyses include cases where there is at least one data point among all assessment periods. For each outcome variable, regression models included a dichotomous variable for treatment condition (1 = MFG, 0 = SAU), and dummy variables signifying each measurement period (baseline as reference). Dummy variables at mid-test, post-test, and 6-month follow-up were included for the Iowa CRS OD scales. As the SSRS and IRS items were not measured at mid-test, only dummy variables for post-test and 6-month follow-up were included for these outcomes. Preliminary analyses of the data examined the level of clustering in the outcome variables presented in this study by MFG groups. Using reliability analysis, we found no evidence of clustering by group as all intraclass correlation coefficients were non-significant, with Cronbach α’s all close to zero. Consequently, we determined that accounting for nesting of MFG participants into groups was not necessary. For all analyses, intercepts were allowed to vary randomly, while regression models included the condition by assessment period dummy variable interactions (e.g., Condition × 6-month follow-up). Individual participant identification variables were used as a second level function. The third level of analysis included family-level identification variables as n = 22 families had more than one child enrolled in the study. Subsequently, we used linear contrasts (e.g., subtracting the sum of all multivariate coefficients for the MFG condition from the sum of all multivariate coefficients for the SAU condition, testing the difference in scores using Z-statistics) to test for significant differences between the MFG and SAU conditions on each outcome variable at 6-month follow-up. Linear contrasts also tested for within-group changes in outcomes over time from baseline to 6-month follow-up. We obtained Cohen’s d effect sizes by dividing each linear contrast estimate with the pooled sample baseline standard deviation for that outcome variable.

Results

Table 2 presents means and standard deviations by treatment group and measurement period. As reported in a previous paper (Chacko et al. in press), significant differences between MFG and SAU groups at post-test were found on the IOWA CRS OD subscale and the SSRS-SSS. Linear contrasts testing differences in outcomes by treatment condition at the 6-month follow-up assessment period are presented in Table 3. Table 3 indicates that improvements in IOWA CRS OD symptoms were maintained at the 6-month follow-up assessment when comparing MFG versus SAU participants (b = −1.17, SE = 0.51, Z = −2.29, p = 0.02, d = 0.34). However, there was no significant difference in SSRS-SSS scores between MFG and SAU groups at the 6-month follow-up assessment. Contrast estimates for the 6-month follow-up assessment indicated significantly reduced levels of impairment for MFG versus SAU participants on the IRS Item no. 1: impairment with playmates (b = −0.40, SE = 0.20, Z = −2.01, p = 0.04), and IRS Item no. 6: overall impairment and need for services (b = −0.39, SE = 0.19, Z = −2.12, p = 0.03), with effect sizes of 0.27–0.35, respectively.

Table 2.

Means and SDs for outcomes measures by time and treatment group

| Variable | MFG

|

SAU

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (N = 220) M (SD) |

Mid-test (N = 174) M (SD) |

Post-test (N = 177) M (SD) |

6-month follow-up (N = 146) M (SD) |

Baseline (N = 95) M (SD) |

Mid-test (N = 70) M (SD) |

Post-test (N = 83) M (SD) |

6-month follow-up (N = 75) M (SD) |

|

| Iowa connors OD | 9.28 (3.37) | 7.73 (3.62) | 7.74 (3.75) | 7.39 (3.87) | 9.05 (3.70) | 8.27 (3.57) | 9.01 (3.81) | 8.83 (4.03) |

| SSRS-SSS | 38.27 (10.64) | 43.59 (11.50) | 43.24 (12.00) | 39.66 (11.09) | 39.72 (10.77) | 41.51 (12.35) | ||

| IRS #1 | 3.60 (1.47) | 2.95 (1.47) | 2.68 (1.27) | 3.66 (1.43) | 2.98 (1.35) | 3.11 (1.35) | ||

| IRS #2 | 3.91 (1.46) | 3.04 (1.48) | 2.89 (1.33) | 3.46 (1.42) | 2.98 (1.36) | 2.97 (1.39) | ||

| IRS #3 | 4.03 (1.55) | 3.33 (1.55) | 3.20 (1.38) | 4.16 (1.51) | 3.55 (1.53) | 3.36 (1.30) | ||

| IRS #4 | 3.95 (1.46) | 3.16 (1.51) | 3.01 (1.34) | 3.75 (1.45) | 3.43 (1.43) | 3.45 (1.35) | ||

| IRS #5 | 4.15 (1.40) | 3.32 (1.47) | 3.17 (1.29) | 3.57 (1.43) | 3.23 (1.37) | 3.33 (1.29) | ||

| IRS #6 | 4.59 (1.15) | 3.49 (1.35) | 3.28 (1.26) | 4.45 (1.06) | 3.68 (1.39) | 3.70 (1.18) | ||

MFG = Multiple Family Group; SAU = Services As Usual; IOWA Connors ODD = Iowa Connors Oppositional/Defiant Subscale; SSRS-SSS = Social Skills Rating Scale Social Skills Subscale; IRS #1 = Impairment Rating Scale Impairment with Playmates; IRS #2 = Impairment Rating Scale Impairment with parents; IRS #3 = Impairment Rating Scale Impairment with Academics; IRS #4 = Impairment Rating Scale Impairment with Self-Esteem; IRS #5 = Impairment Rating Scale Impairment with family; IRS #6 = Impairment Rating Scale Overall Impairment/Need for Services

Table 3.

Tests of between group differences (MFG vs. SAU) at 6-month follow-up

| Outcome variable | No of cases used in analyses | Contrast estimate (b) | SE | Z-statistic | p value | Effect size (Cohen’s d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iowa connors OD | 312 | −1.17 | 0.51 | −2.29 | 0.02* | 0.34 |

| SSRS-SSS | 309 | 1.33 | 1.59 | 0.84 | 0.40 | 0.12 |

| IRS #1 | 316 | −0.40 | 0.20 | −2.01 | 0.04* | 0.27 |

| IRS #2 | 315 | −0.03 | 0.21 | −0.13 | 0.90 | 0.02 |

| IRS #3 | 316 | −0.17 | 0.21 | −0.82 | 0.41 | 0.11 |

| IRS #4 | 316 | −0.39 | 0.21 | −1.83 | 0.07+ | 0.27 |

| IRS #5 | 316 | −0.10 | 0.21 | −0.49 | 0.62 | 0.07 |

| IRS #6 | 316 | −0.39 | 0.19 | −2.12 | 0.03* | 0.35 |

IOWA connors OD = Iowa Connors Oppositional/Defiant Subscale; SSRS-SSS = Social Skills Rating Scale Social Skills Subscale; IRS #1 = Impairment Rating Scale Impairment with Playmates; IRS #2 = Impairment Rating Scale Impairment with parents; IRS #3 = Impairment Rating Scale Impairment with Academics; IRS #4 = Impairment Rating Scale Impairment with Self-Esteem; IRS #5 = Impairment Rating Scale Impairment with family; IRS #6 = Impairment Rating Scale Overall Impairment/Need for Services

p <.10;

p <.05;

p <.01

Table 4 presents linear contrasts for testing changes in outcome from baseline to 6-month follow-up within each treatment group. Change score estimates (6-month follow-up—baseline) indicate significant improvements on the IOWA CRS OD, SSRS-SSS, IRS no. 4: impairment with self-esteem, and IRS no. 5: impairment with family between baseline and 6-month follow-up assessments for the MFG experimental group, but not for participants in the SAU group. Significant improvements for both treatment groups between baseline to 6-month follow-up were also evident for IRS items no. 1: impairment with playmates, IRS no. 2: impairment with parents, IRS no. 3: impairment with academics, and IRS no. 6: overall impairment and need for services. Effect sizes for significant results ranged 0.36–1.16, although effect sizes for the changes were generally higher for the MFG group. Notably, the largest effect size for within group differences was obtained for the IRS no. 6: Overall impairment and need for services for MFG participants (d = 1.16).

Table 4.

Tests of within group differences (6-month follow-up—baseline assessments)

| Outcome variable | No of cases used in analyses | Condition | Contrast estimate | SE | Z statistic | p value | Effect size (Cohen’s d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iowa CRS OD | 312 | MFG | −1.75 | 0.31 | −5.64 | 0.00** | 0.50 |

| SAU | −0.30 | 0.44 | −0.69 | 0.49 | 0.09 | ||

| SSRS-SSS | 309 | MFG | 4.67 | 0.90 | 5.20 | 0.00** | 0.43 |

| SAU | 1.80 | 1.21 | 1.49 | 0.14 | 0.17 | ||

| IRS #1 | 316 | MFG | −0.95 | 0.13 | −7.57 | 0.00** | 0.65 |

| SAU | −0.60 | 0.18 | −3.35 | 0.00** | 0.41 | ||

| IRS #2 | 315 | MFG | −0.99 | 0.13 | −7.73 | 0.00** | 0.68 |

| SAU | −0.53 | 0.18 | −2.89 | 0.00** | 0.36 | ||

| IRS #3 | 316 | MFG | −0.86 | 0.13 | −6.41 | 0.00** | 0.56 |

| SAU | −0.83 | 0.19 | −4.31 | 0.00** | 0.54 | ||

| IRS #4 | 316 | MFG | −0.96 | 0.13 | −7.42 | 0.00** | 0.65 |

| SAU | −0.34 | 0.18 | −1.86 | 0.06+ | 0.23 | ||

| IRS #5 | 316 | MFG | −0.94 | 0.12 | −7.78 | 0.00** | 0.65 |

| SAU | −0.24 | 0.17 | −1.37 | 0.17 | 0.16 | ||

| IRS #6 | 316 | MFG | −1.30 | 0.12 | −11.17 | 0.00** | 1.16 |

| SAU | −0.78 | 0.17 | −4.63 | 0.00** | 0.69 |

IOWA Connors OD = Iowa Connors Oppositional/Defiant Subscale; SSRS-SSS = Social Skills Rating Scale Social Skills Subscale; IRS #1 = Impairment Rating Scale Impairment with Playmates; IRS #2 = Impairment Rating Scale Impairment with parents; IRS #3 = Impairment Rating Scale Impairment with Academics; IRS #4 = Impairment Rating Scale Impairment with Self-Esteem; IRS #5 = Impairment Rating Scale Impairment with family; IRS #6 = Impairment Rating Scale Overall Impairment/Need for Services

p <.10;

p <.05;

p <.01

Discussion

This paper extends prior work on outcomes of the MFG clinical effectiveness trial (Chacko et al. in press) by examining the longer-term outcomes associated with participation in an MFG intervention designed to treat youth DBDs among socioeconomically disadvantaged families compared to SAU in outpatient mental health settings. Findings are presented for the MFG effectiveness study at 6-month follow up on outcomes related to child ODD symptoms, social skills, and impairment across functional domains. Results suggest that improvements found immediately after treatment on some key outcomes (e.g., oppositional behavior) were maintained at 6-month follow up. There was also improvement in certain areas of children’s impairment as reported by parents, specifically the parent’s perceptions of the impact of children’s difficulties on his/her relationship with peers as well as the overall severity of their child’s problems and need for treatment. Finally, results also indicate significant improvement at 6-month follow-up for those in the MFG condition, but not the SAU condition, in child behaviors, social skills, and parent’s perceptions on how children’s difficulties affect their family.

Findings from this study provide further support for MFG in improving oppositional behavior in routine mental health settings. These findings parallel those found in smaller clinical trials of MFG (McKay et al. 2002, 1999). The current study, moreover, extends findings from the smaller clinical trials by reporting maintenance of treatment gains for ODD and improvements in certain functional domains (e.g., relationship with playmates or peers, overall severity of child problems and need for treatment) at 6-month follow-up. Such findings are also consistent with the maintenance of treatment effects from post-test to follow-up assessment periods for similar parent management training programs tested within routine clinic settings (e.g., Axberg and Broberg 2012; Behan et al. 2001; Costin and Chambers 2007; Gardner et al. 2006; Hagen et al., 2011; Hautmann et al. 2009; Kleve et al. 2010; Kling et al. 2010; Kjobli and Ogden 2013; Larsson et al. 2009; Ogden and Hagen 2008).

At the same, findings from the present study are particularly salient given that socioeconomic status (SES) often moderates treatment effects, such that participants with disadvantaged SES tend to show less improvement at follow-up than those with non-disadvantaged SES (e.g., Leijten et al. 2013). Additionally, Lundahl et al. (2006) reported that group-delivered services were less effective than individually delivered treatment for low SES families. This suggests that some youth and their families have difficulties maintaining acute benefits of treatment without active and individualized intervention supports, owing to various socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., few resources) inter-personal (e.g., low levels of social support), and intra-personal (e.g., high levels of stress, psychopathology) factors. Consequently, the present study’s findings are particularly notable, because of a predominant focus on low-income families (compared to more heterogeneous samples in the previously cited studies), exclusive use of group therapy in the experimental condition compared to mostly individual treatment in the SAU condition, and maintenance of improvement in oppositional behavior despite exposure to the high-risk effects of residing in resource-poor communities.

Given that social competence is often impaired in youth with behavioral problems (Maag 2006), there has been a long-standing interest in ameliorating these difficulties. Results for the current study indicate that, although MFG participants manifested significantly greater social skills at post-test compared to SAU participants, this difference between the two conditions decreased at 6-month follow-up and was not significant. Findings from within group analyses indicate, however, that youth social skills for MFG significantly improved from baseline to 6-month follow-up, while such improvement in the SAU condition did not meet statistical significance. Post-hoc analyses of trends over time (not shown) indicate that, while MFG participants’ social skills remained constant from post-test to 6-month follow-up, SAU participants’ social skills improved during this same time period. As such, differences between the two treatment groups at follow-up were no longer statistically significant. Surprisingly, however, caregivers of youth in the MFG group did report that impairment experienced in peer relationships improved relative to youth in the SAU condition at 6-month follow up, effects that were not observed at immediate post-treatment. It may be that improvements in social skills/competence at post-treatment set the stage for subsequent improvements in peer relationships at later points in time. This may be a viable explanation as social skills of a child will likely have to improve first in order for there to be changes in peer relationships.

Similar to what was found with relationship with peers, MFG caregivers reported that the overall impairment/need for treatment was significantly reduced relative to care-givers in the SAU condition at the 6-month follow up point. These differences, however, did not emerge immediately post-treatment. Such findings suggests that relatively short (i.e., 4-month) treatment does not appear to reduce care-giver’s perspectives regarding the overall need for treatment for their child, but that these perspectives change over the course of a 6-month follow-up period. As MFG focuses on the proximal development of skills utilized by each family member which has a downstream impact on improving child behavior, changes in more distal outcomes (perceived need for treatment/overall impairment) likely requires more time to be observed. The data from this study support this contention.

Importantly, the vast majority of studies testing evidence-based parenting- and family-focused interventions targeting disruptive behavior in youth have been efficacy trials prioritizing internal validity of the study (e.g., does the intervention work?). Unfortunately, these types of trials typically have limited external validity (e.g., is the intervention generalizable?) to the typical practice context, given the differences in patient, therapist, and setting characteristics (Hoagwood et al. 2001). The current effectiveness study focuses on the extent to which a treatment can work in applied practice settings. In comparison to other effectiveness studies focused on treatment of youth with behavior disorders in community settings (Axberg and Broberg 2012; Behan et al. 2001; Costin and Chambers 2007; Gardner et al. 2006; Hagen et al. 2011; Hautmann et al. 2009; Kleve et al. 2010; Kling et al. 2010; Kjobli and Ogden 2013; Larsson et al. 2009; Ogden and Hagen 2008), the current study is unique as it has been conducted within typical inner-city community child mental health clinics within the US with a predominantly low-income sample.

Effect sizes for between-group analyses in the current study are consistent with those reported for long-term follow-up among effectiveness studies we reviewed using an active, SAU control group, which is most similar to the current study. Specifically, Kjobli and Ogden (2013) found statistically significant small to medium (i.e., 0.39–0.47) effect sizes in reduction of child behavior difficulties at 6-month follow-up using ITT analyses. Hagen et al. (2011) reported no significant between-group differences on analyses including 1-year follow-up measures on child behavior outcomes using ITT analyses, and only small effect sizes (i.e., 0.08–0.29) among those who actually received treatment. Effect sizes for between group analyses in the current study are also consistent with those reported (average d = 0.30) by Lee et al. (2013) in their analysis of 13 effectiveness studies conducted in routine clinic settings for treating youth DBDs.

Regarding social skills, Kjobli and Ogden (2013) reported a significant small to medium effect size (d = 0.38) for increase in social competence at 6-month follow-up, using ITT analyses. Hagen et al. (2011) reported no significant differences on social competence using analyses incorporating 1-year follow-up assessment measures using ITT analyses, and a small significant effect size (d = 0.29) among those who received treatment. However, the current study indicated only a small, non-significant effect size for between-group analyses on the social skills outcome measure at 6-month follow-up.

Only two effectiveness studies conducted in routine clinic settings that we reviewed (Axeberg and Broberg 2012; Costin and Chambers 2007) included within-group effect sizes for changes in child behavior outcomes including a follow-up assessment period. Axeberg and Broberg reported a large effect size (d = 1.69) in changes in the child behavior difficulties from pre-intervention to 1-year follow-up. Costin and Chambers (2007) reported an overall medium effect size (d = 0.69) for reduction in child behavior symptoms over time including a 5-month follow-up assessment period. In contrast, the within-group effect sizes for the MFG condition assessing changes in child behavior from baseline to 6-month follow-up range from 0.43 to 1.16. The within group effect size for reduction in ODD symptoms (d = 0.50) in the current study is also lower than the average within group effect size (d = 0.68) reported by Lee et al. (2013).

Despite statistically significant differences between treatment conditions at 6-month follow up on oppositional/defiant behaviors and key areas of child impairment, the data indicate that these differences are relatively small. The effect size data also suggest that MFG is unlikely to be sufficient for some families. MFG, a group-based multi-family format, was developed to reduce the barriers to help-seeking and engagement to services that ethnic-minority families typically experience (e.g., stigma) and increase efficiency in service delivery. However, group-formats follow a prescribed format (e.g., content, processes, pace, delivery, duration), which poses significant difficulties in tailoring an intervention to meet the needs of different families. Moreover, the size of the groups (e.g., 6–8 families) may create difficulty during session to address each family’s individual problems. Perhaps augmenting the MFG group with individual family meetings may be useful. Importantly, however, determining for whom and when augmented services are needed is a critical issue in the field. Approaches such as adaptive treatment regimens (Collins et al. 2004) which utilize decision rules during treatment based on an individual’s (or families’) ongoing treatment response (e.g., engagement; attendance, homework completion, etc.) may offer a promising approach to tailoring MFG to those who may need more than the standard MFG group. Evaluating adaptive regimens may be informative, as such a strategy mirrors how clinical decision-making occurs in practice. Specifically, clinicians base their decisions on the course of treatment as a function of their client’s response to the current intervention. It may also be important to provide families with additional “booster” sessions and check-ins during the follow-up time period to maintain treatment gains. These may take the form of monthly MFG support groups for families who wish to continue their interactions with group members from the active treatment period, as well as utilizing family partner advocates to provide individual phone and home visit contact periodically following active treatment. At the same time, some may argue that interventions with small effects, but which can be readily implemented in practice settings (thereby having a broad reach), may be practically more useful than interventions reporting large effects but are impractical for wide-spread implementation in routine practice.

Although findings are promising, this study has limitations suggesting that it should be replicated. More specifically, the block comparative design did not use 1:1 randomization procedures. Although procedures to reduce selection bias were in place, this design limitation exists. In addition, this study is limited by the significant differential attrition by treatment conditions at 6-month follow-up, where MFG participants were less likely to respond at 6-month follow-up compared to SAU participants, suggesting that participants remaining in the sample may not have been representative of the full sample. However, further analyses indicated that minority caregivers were more likely to respond at 6-month compared to White/Caucasian caregivers. Given that minority participants dominated the full sample, the significant association between caregiver ethnicity and response pattern at 6-month follow-up does not indicate that the remaining sample were likely to be unrepresentative of the target population. Moreover, as there were no significant differences by treatment condition on baseline demographic variables among those participants who responded at 6-month follow-up, the threat that attrition reduced sample representativeness appears minimal.

An additional limitation is the exclusive use of parent-report measures of outcomes. Parents may be biased in responding as they are only likely to report on what they can observe (e.g., behavior in the home) compared to behaviors observed at school. Unfortunately, using a larger, more traditional battery of multi-method and multi-reporter assessments used in family-based treatment of DBDs (e.g., independent observations of parent–child interaction) would not have been feasible for this study. The constraints of conducting an effectiveness study within the context of public, community-based, outpatient child mental health clinics as well as enrolling families who were actively seeking treatment necessitated the implementation of measurements that would be least burdensome to families and clinic staff. Future research on MFG will benefit from more recent methodological and technological advances in order to incorporate low-burden assessment instruments (e.g., web-based survey measures sent directly to teachers) in order to reduce reporter bias and gain a more complete picture of participant children’s behavior both at home and in school.

An additional limitation is the use of the IRS as single item, parent-report measures, which typically manifest poor reliability. As noted in the manuscript, investigators attempted to balance brevity with psychometrically valid assessments used in other studies (Chacko et al. 2009). The IRS, in particular, is used as single items to measure impairment across multiple functional domains, rather than collapse items for a single measure of severity. Each item in the IRS has shown strong convergence with other measures of functional impairment that are substantially longer (e.g., Fabiano et al. 2006). Moreover, this study’s results are consistent with the smaller scale and preliminary studies conducted on MFG (McKay et al. 2002, 1999; Stone et al. 1996) and incorporated psychometrically valid and treatment-sensitive measures that have been utilized in other studies (e.g., Chacko et al. 2009) increasing confidence in the validity of the positive outcomes reported in this paper.

Given the length and multi-component nature of MFG, future research should examine what features and components are essential for attaining benefits for youth and their families. Methods such as the multiphase optimization strategy (MOST; Collins et al. 2007) allow for the systematic testing of intervention components to better understand “active ingredients” of treatments, thereby resulting in more parsimonious and effective interventions. In addition, process data (e.g., family functioning) collected in this trial are currently being analyzed to better elucidate how MFG has an impact on outcomes, which will further assist in developing a more parsimonious MFG model. Given that 6-month follow-up data may be limited in light of other intervention studies that have found positive effects through even longer term follow-ups, future studies are planned to look at the impact of MFG in longer-term follow-up periods (i.e., 18-month follow-up). This data should further shed light on the clinical utility of the MFG model as well as SAU for youth with DBDs.

In conclusion, MFG can lead to improvements at 6-month follow-up in disruptive behaviors and in overall severity/need for treatment. This is especially important as the study was conducted in a high risk, low-income community and in routine outpatient clinics. Findings from this study are particularly relevant given the transformative changes occurring in child mental health services as a result of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in the US (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010). There are several implications of the MFG intervention for this new system. First, MFG represents an evidence-informed approach that aligns service provision with existing evidence that parent and family processes can bolster child mental health. Second, the MFG protocol has been carefully designed to directly address service disparities in that it targets families least likely to be engaged in typical services. Third, the group format maximizes efficiency and potentially reduces costs of care, although further study is certainly needed in this area. Finally, for a large number of families, participation in MFG was the sole service provided. Consequently, MFG’s flexibility for delivery with high-need families who often do not access services is noteworthy. The ACA will demand flexible, evidence-informed interventions that can reach high-need families and that can be delivered feasibly within the complex landscape of routine community care. As a result, the MFG intervention may make a potential contribution to the types of services needed within the changing healthcare system.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was obtained through R01 MH072649 (PI: McKay). Salary support for this study also came from NIMH (F32MH090614; Gopalan). Dr. Gopalan is also an investigator with the Implementation Research Institute (IRI), at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis; through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (R25MH080916-01A2) and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI)

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Geetha Gopalan, Email: ggopalan@ssw.umaryland.edu, School of Social Work, University of Maryland, 525 West Redwood Street, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA.

Anil Chacko, Department of Applied Psychology, New York University, New York, NY, USA.

Lydia Franco, Silver School of Social Work, McSilver Institute for Poverty, Policy, and Research, New York University, New York, NY, USA.

Kara M. Dean-Assael, Silver School of Social Work, McSilver Institute for Poverty, Policy, and Research, New York University, New York, NY, USA

Lauren E. Rotko, Silver School of Social Work, New York University, New York, NY, USA

Sue M. Marcus, Division of Biostatistics, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

Kimberly E. Hoagwood, Department of Child Psychiatry, New York University, New York, NY, USA

Mary M. McKay, Silver School of Social Work, McSilver Institute for Poverty, Policy, and Research, New York University, New York, NY, USA

References

- Alvidrez J. Ethnic variations in mental health attitudes and service use among low-income African American, Latina, and European American young women. Community Mental Health Journal. 1999;35(6):515–530. doi: 10.1023/a:1018759201290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders—Text revision. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello JE, Burns BJ, Erkanli A, Farmer EMZ. Effectiveness of nonresidential specialty mental health services for children and adolescents in the “Real World”. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(2):154–160. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200002000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleyard K, Egeland B, van Dulmen MHM, Sroufe LA. When more is not better: The role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(3):235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axberg U, Broberg AG. Evaluation of “the incredible years” in sweden: The transferability of an american parent-training program to sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2012;53(3):224–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2012.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrio C. The cultural relevance of community support programs. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51(7):879–884. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.7.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behan J, Fitzpatrick C, Sharry J, Carr A, Waldron B. Evaluation of the parenting plus programme. The Irish Journal of Psychology. 2001;22(3–4):238–256. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N. Therapy with African American inner-city families. In: Mikesell RH, Lusterman DD, McDaniel SH, editors. Integrating family therapy: Handbook of family psychology and systems theory. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1995. pp. 357–371. [Google Scholar]

- Chacko A, Gopalan G, Franco LM, Dean-Assael KM, Jackson JM, Marcus S, McKay MM. Multiple family group service model for children with disruptive behavior disorders: Child outcomes at post-treatment. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. doi: 10.1177/1063426614532690. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacko A, Wymbs BT, Arnold FW, O’Connor B. Enhancing traditional behavioral parent training for single-mothers of children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:206–218. doi: 10.1080/15374410802698388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL. Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):566–579. doi: 10.1037/a0014565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Murphy SA, Bierman KL. A conceptual framework for adaptive preventive interventions. Prevention Science. 2004;5(3):185–196. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000037641.26017.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L, Murphy S, Stetcher V. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and sequential multiple assignment randomization trial (SMART): New methods for more potent eHealth interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32(5s):S112–S118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costin J, Chambers SM. Parent management training as a treatment for children with oppositional defiant disorder referred to a mental health clinic. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;12:511–524. doi: 10.1177/1359104507080979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumville JC, Hahn S, Miles JNV, Torgerson DJ. The use of unequal randomization ratios in clinical trials: A review. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2006;27:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg S, Nelson M, Boggs S. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):215–237. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WEJ, Waschbusch DA, Burrow-sMacLean L. A practical measure of impairment: Psychometric properties of the impairment rating scale in samples of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and two school-based samples. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(3):369–385. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3503_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F, Burton J, Klimes I. Randomised controlled trial of a parenting intervention in the voluntary sector for reducing child conduct problems: Outcomes and mechanisms for change. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(11):1123–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin PJ, Leszcz M, Ennis M, Koopmans J, Vincent L, Guther H, Hunter J. The effect of group psychosocial support on survival in metastatic breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345(24):1719–1726. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan G, Goldstein L, Klingenstein K, Sicher C, Blake C, McKay MM. Engaging families into child mental health treatment: Updates and special considerations. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;19(3):182–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN. Social skills rating system: Manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hagen KA, Ogden T, Bjornebekk G. Treatment outcomes and mediators of parent management training: A one-year follow-up of children with conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40(2):165–178. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.546050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hautmann C, Stein P, Hanisch C, Eichelberger I, Pluck J, Walter D, Dopfner M. Does parent management training for children with externalizing problem behavior in routine care result in clinically significant changes? Psychotherapy Research. 2009;19(2):224–233. doi: 10.1080/10503300902777148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons R, du Toit M, Cheng Y. Supermix: Mixed effects models. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood K, Burns BJ, Kiser L, Ringeisen H, Schoenwald SK. Evidence-based practice in child and adolescent mental health services. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(9):1179–1189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood K, Burns B, Weisz J. A profitable conjunction: From science to service in children’s mental health. In: Burns B, Hoagwood K, editors. Community treatment for youth: Evidenced-based interventions for severe emotional and behavioral disorders. New York: Oxford Press; 2002. pp. 327–338. [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood KE, Cavaleri MA, Olin S, Burns B, Slaton E, Gruttadaro D, et al. Family support in children’s mental health: A review and synthesis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2010;3:1–45. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Conduct disorders in childhood and adolescence. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kjobli J, Ogden T. A randomized effectiveness trial of brief parent training in primary care settings. Prevention Science. 2013;13:616–626. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0289-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleve L, Crimlisk S, Shoebridge P, Greenwood R, Baker B, Mead B. Is the incredible years programme effective for children with neuro-developmental disorders and for families with social services involvement in the “real world” of community CAMHS? Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;16(2):253–264. doi: 10.1177/1359104510366280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kling A, Forster M, Sundell K, Melin L. A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of parent management training with varying degrees of therapist support. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:530–542. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson B, Fossum S, Clifford G, Drugli MB, Handegard BH, Morch W. Treatment of oppositional defiant and conduct problems in young Norwegian children: Results of a randomized controlled trial. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;18:42–52. doi: 10.1007/s00787-008-0702-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Horvath C, Hunsley J. Does it work in the real world? The effectiveness of treatments for psychological problems in children and adolescents. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2013;44:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Leijten P, Raaijmakers MAJ, Orobio de Castro B, Matthys W. Does socioeconomic status matter? A meta-analysis on parent training effectiveness for disruptive child behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2013 doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.769169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl B, Risser HJ, Lovejoy MC. A meta-analysis of parent training: Moderators and follow-up effects. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(1):86–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maag J. Social skills training with students with emotional and behavioral disorders: A review of reviews. Behavioral Disorders. 2006;32:5–17. [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Bannon W. Engaging families in child mental health services. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2004;13:905–921. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Gonzales J, Quintana E, Kim L, Abdul-Adil J. Multiple family groups: An alternative for reducing disruptive behavioral difficulties of urban children. Research on Social Work Practice. 1999;9(5):593–607. [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Gonzales JJ, Stone S, Ryland D, Kohner K. Multiple family therapy groups: A responsive intervention model for inner city families. Social Work with Groups. 1995;18(4):41–56. [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Gopalan G, Franco L, DeanAssael K, Chacko A, Jackson JM, Fuss A. A collaboratively designed child mental health service model: Multiple family groups for urban children with conduct difficulties. Research on Social Work Practice. 2011;21(6):664–674. doi: 10.1177/1049731511406740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Gopalan G, Franco L, Kalogerogiannis KN, Olshtain-Mann O, Bannon W, Umpierre M. It takes a village to deliver and test child and family-focused prevention programs and mental health services. Research in Social Work Practice. 2010;20(5):476–482. doi: 10.1177/1049731509360976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Harrison ME, Gonzales J, Kim L, Quintana E. Multiple-family groups for urban children with conduct difficulties and their families. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(11):1467–1468. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.11.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, McCadam K, Gonzales JJ. Addressing the barriers to mental health services for inner city children and their caretakers. Community Mental Health Journal. 1996;32(4):353–361. doi: 10.1007/BF02249453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Stoewe J, McCadam K, Gonzales J. Increasing access to child mental health services for urban children and their caregivers. Health and Social Work. 1998;23(1):9–15. doi: 10.1093/hsw/23.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson D, Davenport C, Dretzke J, Barlow J, Day C. Do evidence-based interventions work when tested in the “real world”? A systematic review and meta-analysis of parent management training for the treatment of child disruptive behavior. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2013;16:18–34. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Prinz RJ. Enhancement of social learning family interventions for childhood conduct disorder. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108(2):291–307. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea MD, Phelps R. Multiple family therapy: Current status and critical appraisal. Family Process. 1985;24(4):555–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1985.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden T, Hagen KA. Treatment effectiveness of parent management training in Norway: A randomized controlled trial of children with conduct problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(4):607–621. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. (2010). 42 U.S.C. § 18001 et seq.

- Pelham WE, Evans SW, Gnagy EM, Greenslade KE. Teacher ratings of DSM-III—R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders: Prevalence, factor analyses, and conditional probabilities in a special education sample. School Psychology Review. 1992;21(2):285–299. [Google Scholar]

- Prinz RJ, Jones TL. Family-based interventions. In: Essau CA, editor. Conduct and oppositional defiant disorders: Epidemiology, risk factors, and treatment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. pp. 279–298. [Google Scholar]

- Snowden LR. Barriers to effective mental health services for african americans. Mental Health Services Research. 2001;3:181–187. doi: 10.1023/a:1013172913880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone S, McKay MM, Stoops C. Evaluating multiple family groups to address the behavioral difficulties of urban children. Small Group Research. 1996;27(3):398–415. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Loeber R. Developmental timing of onsets of disruptive behaviors and later delinquency of inner-city youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2000;9(2):203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Waschbusch DA, Willoughby MT. Parent and teacher ratings on the iowa Conners Rating Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2008;30(3):180–192. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. Stress: A potential disruptor of parent perceptions and family interactions. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1990;19(4):302–312. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Jensen-Doss A, Hawley KM. Evidence-based youth psychotherapies versus usual clinical care: A meta-analysis of direct comparisons. American Psychologist. 2006;61(7):671–689. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Palinkas LA, Schoenwald SK, Miranda J, Bearman SK Research Network on Youth Mental Health. Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy treating depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in youth: A randomized effectiveness trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Ugueto AM, Cheron DM, Herren J. Evidence-based youth psychotherapy in the mental health ecosystem. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2013 doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.764824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]