Abstract

CONTEXT

Family planning is highly beneficial to women’s overall health, morbidity, and mortality, particularly in developing countries. Yet, in much of sub-Saharan Africa, contraceptive prevalence remains low while unmet need for family planning remains high. It has been frequently hypothesized that the poor quality of family planning service provision in many low-income settings acts as a barrier to optimal rates of contraceptive use but this association has not been rigorously tested.

METHODS

Using data collected from 3,990 women in 2010, this study investigates the association between family planning service quality and current modern contraceptive use in five cities in Kenya. In addition to individual-level data, audits of select facilities and service provider interviews were conducted in 260 facilities. Within 126 higher-volume clinics, exit interviews were conducted with family planning clients. Individual and facility-level data are linked based on the source of the woman’s current method or other health service. Adjusted prevalence ratios are estimated using binomial regression and we account for clustering of observations within facilities using robust standard errors.

RESULTS

Solicitation of client preferences, assistance with method selection, provision of information by providers on side effects, and provider treatment of clients were all associated with a significantly increased likelihood of current modern contraceptive use and effects were often stronger among younger and less educated women.

CONCLUSION

Efforts to strengthen contraceptive security and improve the content of contraceptive counseling and treatment of clients by providers have the potential to significantly increase contraceptive use in urban Kenya.

Family planning plays an important role in reproductive rights and the protection of maternal health, yet is underutilized in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Regionally, approximately 20 percent of married women are modern method users and, on average, one in four women has a desire to space or limit pregnancy but is not using a modern contraceptive method [1]. While family planning programs in developing countries have worked to increase service delivery points and expand into remote areas, effective programs must also address quality-related issues in the populations they serve [2]. Many family planning experts hypothesize that low-quality family planning services may act as a barrier to more widespread contraceptive use [3–6].

Substantial increases in contraceptive use and corresponding declines in fertility have been consistently observed throughout the developing world in previous decades, although the degree of contraceptive increase and fertility decline has been limited in sub-Saharan Africa relative to other developing regions [7]. In Kenya, the prevalence of contraceptive use has increased since the 1970s, at which time only seven percent of married women of reproductive age used any method of family planning [8]. By 1998, this figure had grown to nearly 40 percent [8]. As contraceptive use has increased, Kenya’s total fertility rate has dropped from more than eight children per woman in the early 1970’s to approximately five children by the late 1990s. However, progress over the last 15 years has been much slower; Kenya’s current contraceptive prevalence has only increased seven percentage points since 1998 and the average woman in Kenya still has between four and five children [8, 9].

Motivated by the hypothesis that improvements in service quality may facilitate greater contraceptive use, two prior large-scale, facility-level, quantitative studies have assessed the quality of family planning service delivery in health care facilities in Kenya. Kenya’s first nationwide assessment of family planning quality was conducted in 1989 among 99 randomly selected public facilities; this study found several deficiencies in service quality including restricted choice of methods, little information on management of side effects, failure on the part of providers to ascertain the client’s reproductive goals, and a dearth of mechanisms in place to ensure follow-up [10]. Results from a subsequent study in 1993, focusing on public facilities in Nairobi, did not differ markedly from the national study [11].

Prior studies in Kenya have described the quality of family planning service delivery, but have been unable to assess the relationship between quality of care and current contraceptive use. Such an assessment typically requires both facility- and individual-level data as well as the ability to link women to a facility where they report or are assumed to receive services. A limited number of studies have taken this type of multi-level approach to assessing the relationship between family planning service quality and contraceptive prevalence or continuation, with mixed results. Three studies conducted in Peru, Egypt, and Morocco in the late 1980s and early 1990s found little to no effect of quality on method use or continuation [12–14]. Conversely, studies conducted between 1991 and 2003 in Tanzania, Egypt, the Philippines, and Nepal found moderate to strong associations between service quality and use [15–18]. Possible explanations for conflicting results among existing multi-level studies include variations in the way that quality is defined and measured. For example, a 1988 study in Egypt found no significant relationship between quality and continued method use yet measured quality solely through interviews with staff and defined quality by the number of trained personnel, number of available methods, and presence of female doctors [12]. In contrast, a 2003 study in Egypt found a significant association between quality and use and measured quality with a variety of tools including provider and client interviews and observations and created a quality of care index [17].

Studies which fail to find a notable link between quality and use may accurately reflect the absence of a strong relationship between the two. However, it is possible such null findings are a result of measurement error, as suggested by the wide variation in approaches to measuring and defining family planning service quality. It should also be noted that prior multi-level studies linked women to a facility based on her location. This linking strategy assumes that women seek services at health care facilities within the geographic cluster to which they have been assigned. Some have suggested this assumption should not be made and instead women participating in demographic surveys should be asked to report the facility where they seek services in order to ensure correct exposure classification [19].

The objective of this study is to investigate the relationship between family planning service quality and current contraceptive use among women in urban Kenya; our ability to link women’s contraceptive use to facility-level quality at a health care facility where she reports receiving care addresses an important research gap. As urban populations in Africa are expected to double between 2000 and 2030 [20], a focus on urban women is timely. We hypothesize that those women attending facilities with higher quality services, compared to those receiving poor quality services, will be more likely to be using modern contraception. It is also possible that the effect of high quality services on use of modern contraception will be stronger in some demographic subgroups, such as younger or less educated women because these women have fewer resources to compensate for low quality services.

METHODS

Data

This study utilizes data from the Measurement, Learning & Evaluation (MLE) Project, implemented by the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In 2009, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the Urban Reproductive Health Initiative (Urban RH Initiative), a five-year project to increase the contraceptive prevalence rate in select urban areas of Kenya, Senegal, Nigeria, and Uttar Pradesh, India. The MLE project is a six-year endeavor to evaluate this initiative. The country-level program of the Urban RH Initiative in Kenya, Tupange, is led by Jhpiego, an international health organization affiliated with The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

In Kenya, the MLE/Tupange study collected baseline data at both the individual (N=8,932) and facility levels (N=279). Individual-level baseline data collection was conducted between September and November 2010 and facility-level baseline data collection was conducted between August and November 2011 in five urban areas in Kenya. In this multi-level analysis, the exposure of service quality is measured at the facility level and the outcome of contraceptive use is measured at the individual level. Although exposure data were collected up to one year after the collection of outcome data, we do not suspect any meaningful changes in family planning service quality occurred between September 2010 and November 2011 as Tupange did not implement facility-level quality improvement activities until after all baseline data were collected.

Individual-level data

Individual-level baseline data collection for the MLE/Tupange study involved a multi-stage sampling design in which government census enumeration areas in each city served as primary sampling units (PSUs) for obtaining a representative sample of women from each city. Within each selected PSU, a random sample of 30 households was selected for household interview; a listing of usual household residents was obtained during the household interview and from this list all eligible women (ages 15–49) were asked to participate via an informed consent protocol. The response rate for the individual women’s questionnaire was 85 percent and survey weights were used to account for non-response and differentials in selection probability.

Respondents were asked about current contraceptive use, demographic characteristics, and fertility desires, among other things. The baseline individual questionnaire also collected data on the source of the woman’s current contraceptive method, current maternal and child health services, current vaccination services, and current HIV services. This information was used to link women in the individual-level survey to a facility where they recently received health care services. This linking strategy is based on the hypothesis that the quality of family planning service delivery at the facility where a woman reports actually receiving services will impact her decision to use contraception, i.e. that her direct experience at a facility is a key factor in contraceptive use rather than the quality of the facility in a woman’s nearest proximity or the average level of quality among facilities in her geographic area.

Of the 8,932 women in the original sample, a total of 692 women were excluded from this analysis because they reported being currently pregnant or unable to become pregnant for reasons such as menopause or hysterectomy. These women are not in need of contraception. Similarly, an additional 762 women were excluded because they reported a desire to become pregnant now. Lastly, 1,871 women were excluded because they reported not receiving any type of health care service at a facility; these women are not eligible for this analysis because only those women receiving health services in a facility have any possibility of being exposed to service quality. For women not entering a health care facility, our research question is not relevant and we are not intending to apply our results to this population. In total, 3,259 women were excluded from the analysis, leaving 5,673 eligible women.

Facility-level data

In addition to individual-level data, the MLE/Tupange study attempted to collect data at 286 service delivery points, including hospitals, health centers, and clinics that offer family planning or maternal and child health services. The selected facilities included those where the Tupange initiative planned to implement quality improvement activities as well as those facilities identified by women in the individual survey as locations where they go for family planning services (preferred providers). The MLE/Tupange study also attempted to include a census of public facilities. Of the 286 selected facilities, two were unable to participate in the audit due to lack of staff availability while another five facilities refused participation, for a participation rate of 97.6 percent. Nineteen of the 279 participating facilities were excluded from this study because they do not provide family planning services, resulting in a final sample size of 260 facilities. These 260 facilities represent approximately 44 percent of all operational health care facilities with family planning provision in the five study cities. Approximately 60 percent of all operational hospitals with family planning services were included and more than half of the excluded facilities were smaller, private-sector facilities, according to the Kenya Master Health Facility List [21]. Three types of facility-level data were collected within these sites: facility audits, provider interviews, and client exit interviews. The last of these, client exit interviews, were only conducted in higher volume facilities (n=152) with sufficient flow of clients.

The facility audit, conducted in collaboration with a manager, collected data on training and experience profiles of staff, services provided, integration of available services, and the provision and availability of each of 12 types of family planning methods. The audit also checked for adequacy of storage and standard operating procedures, and the presence of certain basic items such as sterile equipment, electricity, running water, and private exam rooms.

Of the 260 participating facilities providing family planning services, provider interviews were collected at 255 facilities. Between one and four providers were interviewed at each facility and, within those facilities with five or more service providers, four providers were chosen at random. Health care providers were asked to provide their informed consent to participate in the survey and were asked questions on pre-service and in-service training, counseling procedures for family planning, integration of family planning with other health care services, and quality assurance, among other things. A total of 692 providers were selected for interview. Seven of those selected did not complete an interview due to lack of available time (n=3), or refusal (n=5), for a participation rate of 99.0 percent.

Client exit interviews were conducted with a convenience sample of 4,230 women visiting one of the 152 higher volume facilities for services such as family planning, maternal and child health, HIV management or testing and counseling, or curative services. Interview eligibility was determined at the completion of each woman’s facility visit using a screening question to find out what service they received. Interviews were conducted at each facility for a period of one to five days, depending on the client volume at each clinic. Among exiting clients who reported family planning as the main health service they came to the facility to receive that day, client exit interviews collected data on number of methods discussed by the provider, wait time, client satisfaction, perceived treatment, and information given during the counseling session on topics including side effects, method use, and when to return to the facility. This analysis includes only data from exiting clients whose main reason for a facility visit was to initiate or continue contraceptive use. Therefore client exit interview data from a total of 1,316 women attending 126 higher-volume facilities are used here.

Outcome Variable

The outcome of interest, current modern contraceptive use, was measured at the individual level during baseline data collection in 2010. This was measured by asking participants which method(s), if any, they (or their partner) were currently using. For the purposes of this analysis, modern methods include the following: condoms, pills, injectables, implants, intrauterine devices, sterilization, emergency contraception, spermicide, and the lactational amenorrhea method. A small number of participants (5 percent in the women’s weighted sample) using traditional methods (the rhythm method, withdrawal, or standard days method) were classified as not using modern methods.

Independent Variables

Exposure classification is guided by a standardized quality of care framework developed by researchers at The Population Council in 1990 which includes the following six elements: choice of methods, information given to user, provider competence, client provider relations, continuity or follow-up mechanisms, and appropriate constellation of services [22]. The specific questions within each survey instrument that were used to measure each quality element, as well as information on the coding of these variables, are included in the appendix (Table A1).

Choice of Methods. Choice of methods is determined by the physical availability of a satisfactory selection of methods as well as willingness on the part of the provider to discuss multiple methods and to ascertain client preferences [11].

Information Given to Clients. Providing information to clients means that clients receive information from their service provider to assist with the selection and proper use of and management of side effects for their selected method as well as potential warning signs [23].

Provider Competence. A competent provider is one who demonstrates adequate technical competence and adherence to medical guidelines and protocols [22].

Interpersonal Relations. Interpersonal relations can be viewed as the personal or human aspect of service provision, such as respectful treatment and bi-directional communication [24].

Continuity and Follow-up: This element of quality ensures that follow-up mechanisms are in place, such as scheduling of future appointments or home visits, to encourage contraceptive continuity [22].

Appropriate Constellation of Services: Integrating family planning into additional health services such as child immunizations, postpartum care, and HIV-related care ensures convenient access to services [23].

In preparing to assess the relationship between quality and contraceptive use, some researchers have suggested that achieving a high level of service quality may not be realistic in the absence of adequate service infrastructure [25, 26]. RamaRao (2003) [27] notes that program managers have cited deficiencies in the service infrastructure as a key barrier to providing good quality services. As such, the term “quality” can be expanded to include not only the dynamics of the interaction between the provider and client but also the degree to which facilities are prepared to offer services. For this reason we also include variables related to facility infrastructure including basic items, family planning guidelines, and quality assurance measures.

Lastly, we consider the relationship between client satisfaction and current contraceptive use, in which client satisfaction serves as a proxy for high quality services. Components of client satisfaction in this analysis include overall satisfaction with services, satisfaction with amount of wait time, satisfaction with amount of information provided, client belief that they will use the facility again, and client agreement to recommend the facility to others. These variables are only available for higher volume facilities.

Coding of Independent Variables

With the exception of the variable representing the number of methods provided, available, or not out-of-stock, which was coded as a continuous variable (range = 0 to 8), all variables from the facility audit were coded as binary variables. As previously mentioned, between one and four provider interviews were conducted at each of 255 participating facilities; for each quality indicator, the proportion of providers at each clinic responding affirmatively was calculated, and clinics were then dichotomized as having a provider proportion of positive responses at/above versus below the sample-wide proportion for that indicator. Between one and 44 client interviews were conducted at each facility and relevant quality-related variables from this instrument were also averaged for each facility; once averaged, client interview variables were entered into the model as continuous variables. Before being entered into the model, client variables were multiplied by 4 to range from 0–4, so that estimated prevalence ratios reflect the change in contraceptive prevalence associated with a 25 percentage point increase in that indicator.

Covariates

Based on our knowledge of their relationship with both quality of care and contraceptive use, the following variables were included as covariates in this multivariate analysis: age, marital status, religion, education, wealth, and residence (slum or non-slum location). These covariates were measured at the individual level using data from the women’s questionnaires administered at baseline and were included in the multivariate model as indicator variables. See Table 1 for categorization of these variables.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of women ages 15 to 49 in urban Kenya, 2010.

| Women included in the analysis | Women excluded from the analysis because they link to a non-MLE facility | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| N=3246* | % | N=2399* | % | |

|

|

|

|

||

| Age | ||||

|

|

|

|

||

| 15–19 | 184 | 6% | 232 | 10% |

| 20–24 | 886 | 27% | 814 | 34% |

| 25–29 | 967 | 30% | 565 | 24% |

| 30–34 | 608 | 19% | 325 | 14% |

| 35–39 | 352 | 11% | 256 | 11% |

| 40–49 | 249 | 8% | 207 | 9% |

| Missing | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

|

|

|

|

||

| Education | ||||

|

|

|

|

||

| No education | 68 | 2% | 72 | 3% |

| Primary Incomplete | 442 | 14% | 261 | 11% |

| Primary Complete | 942 | 29% | 564 | 24% |

| Secondary plus | 1795 | 55% | 1501 | 63% |

| Missing | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

|

|

|

|

||

| Religion | ||||

|

|

|

|

||

| Catholic | 764 | 24% | 626 | 26% |

| Protestant/other Christian | 2183 | 67% | 1581 | 66% |

| Muslim/none/other | 295 | 9% | 190 | 8% |

| Missing | 4 | 0% | 2 | 0% |

|

|

|

|

||

| Marital Status | ||||

|

|

|

|

||

| Currently married | 2367 | 73% | 1206 | 50% |

| Not currently married | 869 | 27% | 1188 | 50% |

| Missing | 10 | 0% | 5 | 0% |

|

|

|

|

||

| Parity | ||||

|

|

|

|

||

| No children | 322 | 10% | 726 | 30% |

| 1 child | 996 | 31% | 696 | 29% |

| 2 children | 883 | 27% | 455 | 19% |

| 3 children | 516 | 16% | 259 | 11% |

| 4 or more children | 528 | 16% | 264 | 11% |

| Missing | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

|

|

|

|

||

| Fertility Intentions | ||||

|

|

|

|

||

| Wants a pregnancy later | 1630 | 50% | 1441 | 60% |

| Does not want a pregnancy | 1408 | 43% | 781 | 33% |

| Not sure she can get pregnant | 16 | 1% | 18 | 1% |

| Other | 20 | 1% | 18 | 1% |

| Doesn’t know | 160 | 5% | 135 | 6% |

| Missing | 12 | 0% | 6 | 0% |

|

|

|

|

||

| City | ||||

|

|

|

|

||

| Nairobi | 2269 | 70% | 1967 | 82% |

| Mombasa | 599 | 18% | 320 | 13% |

| Kisumu | 236 | 7% | 77 | 3% |

| Machakos | 61 | 2% | 20 | 1% |

| Kakamega | 81 | 2% | 15 | 1% |

| Missing | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

|

|

|

|

||

| Wealth | ||||

|

|

|

|

||

| Poorest | 594 | 18% | 396 | 16% |

| Poor | 702 | 22% | 429 | 18% |

| Middle | 715 | 22% | 505 | 21% |

| Rich | 663 | 20% | 476 | 20% |

| Richest | 573 | 18% | 591 | 25% |

| Missing | 0 | 0% | 3 | 0% |

|

|

|

|

||

| Residence | ||||

|

|

|

|

||

| Slum | 790 | 24% | 406 | 17% |

| Non-Slum | 2456 | 76% | 1993 | 83% |

| Missing | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

All numbers and percentages are weighted.

Statistical Analysis

After exploring the facility audit instrument and the questionnaires for interviewing family planning providers and clients, we identified a total of 48 variables related to facility level service quality, infrastructure, or client satisfaction. Such a large number of exposure variables can complicate the presentation of results. Additionally, there is the potential for correlation among related variables. For this reason, we employed factor analysis as a means of reducing the number of quality-related exposure variables in this analysis from 48 to 35. The following sets of variables were grouped together based on an alpha greater than 0.70 and a Factor 1 Eigenvalue greater than 1.0, suggesting the observed variables in each group have a similar pattern of response and are appropriately grouped for the purposes of data reduction:

Method choice, measured by facility audits (variables grouped together include: number of methods provided, mix1 of methods provided, number of methods currently available, mix of methods currently available)

Method choice, measured by client interviews (variables grouped together include: provider provided information about different FP methods, provider asked the client about her method of choice)

Information given, measured by client interviews (variables grouped together include: provider explained how to use the method, provider talked about possible side effects, provider told client what to do if they have any problems)

Bidirectional communication, measured by client interviews (variables grouped together include: provider asked the client if she had any questions, client felt comfortable to ask questions during the visit, provider answered all of the clients questions)

Presence of basic items and private exam room, measured by facility audits (variables grouped together include: are the following items available on a functioning basis: running water, electricity, blood pressure cuff, speculum and is there a private examination room)

Client satisfaction, measured by client interviews (variables grouped together include: client would use this facility again and would recommend it to others)

We estimated prevalence ratios using binomial regression. The model was stabilized by using the Poisson distribution for the residuals. Each of the 35 exposure variables was entered into a separate model with the same covariates. We accounted for clustering of observations within facilities using robust standard errors. Our presentation of results includes two models: one model includes the full sample of women while the alternative model includes only those women who linked to a higher volume facility; this was done because client data were only collected at the higher volume facilities.

RESULTS

Descriptive Results

Sample of women. A total of 5,673 eligible and consenting women completed the individual women’s questionnaire. Of the eligible women, 3,990 (approximately 70 percent) could be linked to a facility for which the MLE/Tupange study collected quality-related facility-level data at baseline in 2011. Of these 3,990 women, 3,083 were linked to a facility of higher volume where data from exiting family planning clients were collected. More than half (57 percent) of the women in the weighted sample were between 20 and 29 years of age and a similar number (55 percent) completed at least a secondary education (Table 1). Most were Protestant, currently married, and had experienced at least two live births. More than two thirds (70 percent) of the weighted sample resided in Nairobi and approximately one fourth (24 percent) resided in slum-like conditions.

Outcome prevalence. Slightly less than two-thirds (65 percent) of the 3,990 women included in this analysis were currently using a modern contraceptive method (i.e. dependent variable positive, Table 2). Close to half of the 2,267 women using contraception were using injectable contraception (45 percent). Another fifth were using the pill (22 percent). Around 15 percent of method users in the weighted sample were using long-acting or permanent methods including the IUD, the implant, or female or male sterilization.

Table 2.

Family planning and specific method use among women ages 15 to 49 in urban Kenya, 2010.

| Women included in the analysis | Women excluded from the analysis because they link to a non-MLE facility | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| N=3246* | % | N=2399* | % | |

|

|

|

|

||

| Family Planning Use | ||||

|

|

|

|

||

| Modern Method | 2119 | 65% | 1402 | 58% |

| Traditional Method | 148 | 5% | 114 | 5% |

| Non-use | 979 | 30% | 882 | 37% |

|

|

|

|

||

| Method Mix | N=2267* | % | N=1516** | % |

|

|

|

|

||

| Female/Male Sterilization | 50 | 2% | 30 | 2% |

| Pill | 491 | 22% | 352 | 23% |

| Intrauterine Device | 116 | 5% | 56 | 4% |

| Injectable | 1023 | 45% | 495 | 33% |

| Male Condom | 200 | 9% | 370 | 24% |

| Implant | 173 | 8% | 38 | 2% |

| Other Modern Method | 66 | 3% | 62 | 4% |

| Traditional Method | 148 | 7% | 114 | 8% |

All numbers and percentages are weighted

In order to examine whether there were selection effects with respect to the users of facilities included in the baseline survey, we considered background characteristics and method use among women excluded because they linked to a facility not included in the MLE baseline facility-level survey (Tables 1 and 2). Significant differences between excluded women and the women we included in our analysis suggest the sample of facilities included at baseline attract a different set of women by marital status and parity. Those excluded because they went to a facility not included in the MLE baseline survey were twice as likely as included women to be unmarried and three times as likely to be nulliparous (Table 1). Excluded women were also more likely to rely on condoms for pregnancy prevention (Table 2).

Sample of facilities. One third of the health care facilities selected for the facility-level baseline survey were public facilities and the majority of these public facilities (84 percent) were non-hospital facility types such as health centers and dispensaries (Table 3). Among private facilities, a similar amount (87 percent) was smaller in size than hospitals, such as clinics and maternity homes. On average, each of these facilities employed nine service providers and, on average, the MLE project interviewed 10 clients at each of the higher volume facilities.

- Quality of care.

-

○Facility audit data (Table 4a). Regarding method choice, on average, the facilities included in this analysis provided seven contraceptive methods, but had fewer than six methods currently available at the time of the facility audit, and had only about four methods that had not been stocked out at some point in the previous year. According to responses from facility supervisors, integration of family planning with other health care services (including child health services, postnatal services, and HIV-related services) is fairly widespread, occurring in at least 78 percent of all facilities in the sample. Regarding infrastructure, the majority of facilities (79 percent or more) have private exam rooms, running water, electricity, and basic items often used in the provision of family planning methods such as blood pressure cuffs and specula. Far fewer facilities could point to the presence of national family planning guidelines within the facility (52 percent) and even fewer could demonstrate quality assurance measures (39 percent).

-

○Provider interview data (Table 4b). With respect to method choice, while most providers (81 percent) reported discussing multiple methods with their clients, less than half of providers (48 percent) reported asking their clients about their family planning preferences. For indicators related to information given to users, between approximately 30 and 50 percent of providers offered information to clients such as helping with method selection, explaining method use, and discussing potential warning signs; larger numbers of providers (81 percent) reported explaining possible side effects of the client’s chosen method. This analysis uses training as a proxy for technical capacity. Exactly half of the providers interviewed reported that they had received in-service training on the provision of family planning services. For follow-up practices, nearly all providers (93 percent) report informing their family planning clients when to return to the facility for method resupply; this represents follow-up mechanisms. Regarding integration, providers self-reported slightly lower levels of integrated services than found with facility audit data. According to these reports, family planning is integrated into child health services by 72 percent of providers, into postnatal services by 70 percent of providers, and into HIV-related services by 81 percent of all providers interviewed at baseline.

-

○Client interview data (Table 4c). According to client interview data pertaining to method choice, around half of clients (47 percent) received information on multiple methods and a slightly higher percentage (57 percent) was asked about their method of choice. Client reports of the information offered by providers differed from provider responses, with approximately two-thirds reporting their provider explained proper method use and discussed how to manage problems while just 58 percent said their provider discussed potential side effects. Regarding the relationship between providers and clients, around one third of clients reported their provider asked about their reproductive goals and treated them very well, while approximately one fifth of clients said other staff within the facility treated them very well. Indicators used to measure client reports of whether the provider solicited questions, whether the client felt comfortable asking questions, and whether all questions were answered by the provider, ranged from 66 to 91 percent. In terms of client satisfaction, approximately nine out of ten clients felt they had adequate privacy during their visit, believed in the confidentiality of their services, felt they received the right amount of information, and were satisfied with services overall. Clients reported nearly universally that they would use the same facility again and would recommend it to others. Fewer clients – only 3 out of 4 – were satisfied with the amount of time they had to wait for services.

-

○

Table 3.

Characteristics of select health care facilities surveyed by MLE/Tupange in urban Kenya, 2011.

| Total health care facilities | N= 260 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Public Facilities | N=87 | 33% |

| Public hospitals Other types of public facilities |

14 73 |

16% 84% |

| Private Facilities | N= 173 | 67% |

| Private hospitals Other types of private facilities |

22 151 |

13% 87% |

| Mean (Range) | ||

| Providers interviewed per facility | 3 (1–4) | |

| Providers per facility, overall | 9 (1–267) | |

| Family planning clients interviewed per facility | 10 (1–44) | |

Table 4.

Quality of care in select health care facilities surveyed by MLE/Tupange in urban Kenya, 2011.

| A: FACILITY AUDITS | N=260 facilities | |

|---|---|---|

| Choice of methods | ||

|

| ||

| Mean number of methods provided (range) | 7.3 (1–12) | |

| Mean number of methods provided and currently available (range) | 5.5 (0–8) | |

| Mean number of methods provided and not out of stock in the previous year (range) | 3.8 (0–8) | |

| Facilities with at least one long-acting, one shorter-term, and one barrier method provided | 63.1% | |

| Facilities with at least one long-acting, one shorter-term, and one barrier method provided and currently available | 55.8% | |

| Facilities with at least one long-acting, one shorter-term, and one barrier method not out of stock in previous year | 33.1% | |

|

| ||

| Integration | ||

|

| ||

| Facilities integrating family planning with child health services | 85.8% | |

| Facilities integrating family planning with post natal care services | 78.1% | |

| Facilities integrating family planning with HIV services | 90.0% | |

|

| ||

| Infrastructure or facility “readiness” | ||

|

| ||

| Facilities with a private exam room | 87.3% | |

| Facilities with water | 78.5% | |

| Facilities with electricity | 93.9% | |

| Facilities with blood pressure cuff | 95.4% | |

| Facilities with a speculum | 82.3% | |

| Facilities with family planning guidelines | 51.5% | |

| Facilities with quality assurance measures in place | 38.9% | |

| B: PROVIDER INTERVIEWS | N=648 providers | |

|---|---|---|

| Choice of methods | ||

|

| ||

| Provider discusses different FP methods with clients | 80.9% | |

| Provider asks the client about their preferred method | 47.5% | |

|

| ||

| Information given to users | ||

|

| ||

| Provider helps clients select a method | 43.1% | |

| Provider explains how to use the selected method to clients | 52.6% | |

| Provide r explains side effects of selected method to clients | 81.0% | |

| Provider discusses potential warning signs related to selected method with clients | 29.8% | |

|

| ||

| Provider competence | ||

|

| ||

| Provider received in-service training in FP provision | 50.0% | |

|

| ||

| Client-Provider relations | ||

|

| ||

| Provider discusses reproductive goals with clients | 44.0% | |

|

| ||

| Integration | ||

|

| ||

| Provider integrates family planning with child health services | 72.1% | |

| Provider integrates family planning with post natal care services | 70.2% | |

| Provider integrates family planning with HIV services | 80.9% | |

| C: CLIENT INTERVIEWS | N=1315 clients | |

|---|---|---|

| Choice of methods | ||

|

| ||

| Provider told client about different FP methods | 46.7% | |

| Provider asked client about their method of choice | 56.7% | |

|

| ||

| Information given to users | ||

|

| ||

| Provider helped client select a method (n=472; new and switching clients only) | 40.7% | |

| Provider explained to client how to use selected method (n=472; new and switching clients only) | 65.9% | |

| Provider told client about possible side effects of chosen method | 57.6% | |

| Provider discussed with client what to do if client has problems with method (n=472; new and switching clients only) | 64.6% | |

|

| ||

| Client-Provider relations | ||

|

| ||

| The provider asked client about their reproductive goals | 34.8% | |

| Provider treated client very well | 33.4% | |

| Other facility staff treated client very well | 21.3% | |

| Provider asked client if they have any questions | 66.4% | |

| Client felt comfortable asking questions during the visit | 91.1% | |

| Provider answered all of the client’s questions | 79.1% | |

|

| ||

| Follow-up mechanisms | ||

|

| ||

| Provider informed client when to return for resupply | 93.4% | |

|

| ||

| Client satisfaction | ||

|

| ||

| Client believed other clients could not see them | 83.9% | |

| Client believed that other clients could not hear them | 93.8% | |

| Client believed that their information will be kept confidential by the provider | 87.3% | |

| Client believed that they received the right amount of information (not too much and not too little) | 91.0% | |

| Client felt wait time was satisfactory | 76.3% | |

| Client felt satisfied with services | 91.8% | |

| Client will use this facility again | 98.9% | |

| Client will recommend this facility to others | 97.8% | |

Multivariate Analyses

Facility Audit Data (Table 5a). Within the full sample of facilities that includes both higher and lower volume facilities (Model 1), one aspect of method choice measured by the facility audit was marginally significant in its associated with current modern method use: providing a mix of methods that have not been stocked out in the previous year (adjusted prevalence ratio of 1.1). Within the sample that includes only higher volume facilities (Model 2), a consistently stocked mix of methods also has a significant relationship to family planning use and the magnitude of the effect is slightly larger than in the unrestricted sample of facilities (prevalence ratio of 1.2).

Provider Interview Data (Table 5b). Method choice was also significantly associated with contraceptive use when measured by provider interviews. In particular, within the restricted sample (Model 2), women attending facilities where providers report asking clients about their family planning preferences were significantly more likely to use contraception (prevalence ratio 1.1). Regarding information offered to clients, in the full sample, women attending facilities where providers report discussing side effects were significantly more likely to be current family planning users (prevalence ratio 1.1), although this effect was not seen in the restricted sample of facilities.

Client Interview Data (Table 5c). Two aspects of quality were found to have a significant relationship with contraceptive use when measured by client self-reports: information given to users and provider-client relations. With respect to information given to users, in the restricted sample of facilities, those women attending facilities where clients report receiving help with method selection had a six percent greater likelihood of current contraceptive use for each 25 percentage point increase in this indicator. Therefore an increase from 41 percent of providers reporting discussion of side effects to 66 percent of providers reporting the same will correspond to a six percent greater likelihood of contraceptive use. Regarding client-provider relations, women attending facilities where exiting clients reported being treated very well by their provider had a 10 percent greater likelihood of current contraception use compared to women attending facilities where this was not the case. No other measurements of a positive provider-client relationship – such as discussion of reproductive goals, treatment by other staff, or bidirectional communication – appear to be significantly associated with contraceptive use in this population. Regarding client satisfaction, women attending facilities where exiting clients reported visual privacy were significantly less likely to be current contraceptive users (prevalence ratio, 0.9). Those women attending facilities where exiting clients reported they would use the facility again and/or recommend to others were 1.2 times as likely to be current users as women attending facilities where clients reported they would not return to or recommend the facility. Other indicators of client satisfaction such as audial privacy, and satisfaction with information or wait times, as well as overall satisfaction with services, had no relationship with current contraceptive use among women in this sample.

Across all three types of data collection instruments, provider competence, follow-up mechanisms, integration, and facility infrastructure showed no relationship to contraceptive use. We found no association between provider in-service training in FP provision and current use. Similarly, we did not find increased likelihood of contraceptive use among women attending facilities where exiting clients reported receiving information on when to return for follow-up services. We also found no significant association between contraceptive use and the integration of family planning into other health services, as measured by both facility audits and provider reports. Lastly, no aspect of facility infrastructure was associated with current modern method use.

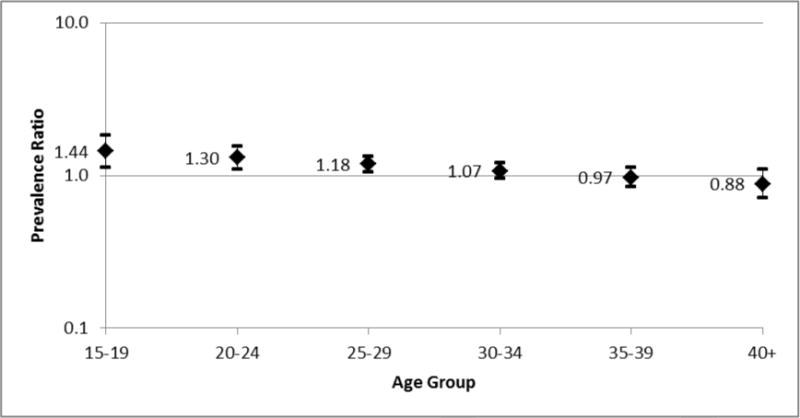

We found that these results are modified by both age and education. In general, the association between several aspects of quality and contraceptive use was much stronger for younger women and those who were less educated. Figure 1 demonstrates modification by age of the relationship between the provider’s treatment of the client and current contraceptive use. This figure illustrates an effect of client treatment on contraceptive use in the younger age groups that is diminished in the older age groups. The effect of provider treatment on contraceptive use is strongest among women 15 to 19 years of age (prevalence ratio of 1.4). As age increases, the effect of client treatment on contraceptive use is diminished such that, for women ages 35 or more there is no significant relationship between client treatment and contraceptive use. A similar relationship was observed for some aspects of quality and education, where the magnitude of effect was strongest among the least educated women. For example, the effect of a provider offering the client a choice of methods is strongest among women without any education (prevalence ratio or 1.3, data not shown) and this effect diminishes as educational attainment increases.

Table 5.

Multivariate binomial regression examining the relationship between quality of care and current use of modern contraception among women ages 15 to 49 in urban Kenya, 2010.

| A: FACILITY AUDIT DATA |

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a

|

Model 2b

|

|||

| aPR | CI | aPR | CI | |

| Choice of methods | ||||

|

| ||||

| Composite variable for method choice (number and mix of methods available and provided) | 0.98 | (0.91, 1.05) | 1.06 | (0.96, 1.18) |

| Number of methods provided that were not stocked out in the previous year | 1.01 | (0.98, 1.03) | 1.02 | (0.99, 1.05) |

| A mix of methods is provided and not stocked out in previous year | 1.10 | (0.98, 1.23) | 1.15 | (0.99, 1.34) |

|

| ||||

| Integration | ||||

|

| ||||

| Facility audit shows integration of family planning with child health services | 1.09 | (0.93, 1.28) | 1.09 | (0.90, 1.32) |

| Facility audit shows integration of family planning with postpartum services | 1.02 | (0.87, 1.19) | 0.99 | (0.84, 1.17) |

| Facility audit shows integration of family planning with HIV services | 1.05 | (0.90, 1.23) | 1.02 | (0.85, 1.22) |

|

| ||||

| Infrastructure or facility “readiness” | ||||

|

| ||||

| Composite variable for basic items (private exam room, running water, electricity, blood pressure cuff, speculum) | 0.96 | (0.89, 1.05) | 0.99 | (0.89, 1.10) |

| Facility audit shows presence of family planning guidelines | 0.96 | (0.86, 1.07) | 0.92 | (0.79, 1.06) |

| Facility audit shows quality assurance mechanisms in place | 1.05 | (0.95, 1.17) | 1.04 | (0.92, 1.18) |

| B: PROVIDER INTERVIEW DATA |

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a

|

Model 2b

|

|||

| aPR | CI | aPR | CI | |

| Choice of methods | ||||

|

| ||||

| Providers reported discussing different FP methods with clients | 1.02 | (0.91, 1.14) | 1.07 | (0.92, 1.23) |

| Providers reported asking the client about their preference | 1.03 | (0.93, 1.14) | 1.14 | (1.02, 1.28) |

|

| ||||

| Information given to users | ||||

|

| ||||

| Providers report helping with method selection | 1.03 | (0.92, 1.15) | 1.11 | (0.96, 1.29) |

| Providers report giving instructions for use | 1.05 | (0.94, 1.18) | 1.10 | (0.97, 1.26) |

| Providers report discussing side effects | 1.12 | (1.01, 1.23) | 1.08 | (0.95, 1.23) |

| Providers report discussing potential warning signs | 1.06 | (0.96, 1.18) | 1.09 | (0.95, 1.24) |

|

| ||||

| Provider competence | ||||

|

| ||||

| Providers report receiving in-service training in FP provision | 0.95 | (0.85, 1.06) | 0.98 | (0.84, 1.14) |

|

| ||||

| Client-Provider relations | ||||

|

| ||||

| Providers report asking clients about their reproductive goals | 0.99 | (0.88, 1.11) | 1.02 | (0.87, 1.19) |

|

| ||||

| Integration | ||||

|

| ||||

| Providers report integrating family planning with child health services | 1.00 | (0.87, 1.14) | 1.15 | (0.92, 1.43) |

| Providers report integrating family planning with postnatal services | 0.97 | (0.85, 1.10) | 1.05 | (0.88, 1.26) |

| Providers report integrating family planning with HIV services | 1.01 | (0.88, 1.16) | 1.05 | (0.85, 1.28) |

| C: CLIENT INTERVIEW DATA |

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a

|

Model 2b

|

|||

| aPR | CI | aPR | CI | |

| Choice of methods | ||||

|

| ||||

| Composite variable for method choice (client reports being told about different and asked method preference) | NA | — | 1.01 | (0.93, 1.11) |

|

| ||||

| Information given to users | ||||

|

| ||||

| Client reports provider helped them select a method | NA | — | 1.06 | (1.01, 1.11) |

| Composite variable for information (client reports provider discussed proper use, side effects & problem management) | NA | — | 0.96 | (0.86, 1.08) |

|

| ||||

| Client-Provider relations | ||||

|

| ||||

| Client reports being asked about their reproductive goals | NA | — | 1.05 | (0.97, 1.14) |

| Client reports being treated very well by their provider | NA | — | 1.10 | (1.01, 1.19) |

| Client reports being treated very well by other staff | NA | — | 1.06 | (0.95, 1.18) |

| Composite variable for bidirectional communication (provider solicited questions, client felt comfortable asking questions, provider answered all questions) | NA | — | 1.00 | (0.89, 1.11) |

|

| ||||

| Follow-up mechanisms | ||||

|

| ||||

| Clients report their provider informed them when to return | NA | — | 0.97 | (0.87, 1.07) |

|

| ||||

| Client satisfaction | ||||

|

| ||||

| Client believes other clients could not see them | NA | — | 0.92 | (0.85, 1.00) |

| Client believes other clients could not hear them | NA | — | 0.88 | (0.73, 1.05) |

| Client believes their information will be kept confidential by the provider | NA | — | 1.09 | (0.95, 1.26) |

| Client believes they received the right amount of information (not too much and not too little) | NA | — | 0.98 | (0.82, 1.17) |

| Client felt amount of wait time is acceptable | NA | — | 0.97 | (0.89, 1.06) |

| Clients was overall satisfied with services | NA | — | 0.96 | (0.82, 1.14) |

| Composite variable for satisfaction (client would use again and recommend to others) | NA | — | 1.17 | (1.02, 1.35) |

All models are adjusted for age, education, marital status, religion, city of residence, wealth, and slum residence.

Multivariate analysis performed on the full weighted sample size (n=2,949)

Multivariate analysis restricted to only those observations linked to a facility where client exit interviews were conducted (n=1,887)

aPR = Adjusted Prevalence Ratio

Figure 1.

Modification by age of the relationship between client treatment and current contraceptive use among women ages 15 to 49 in urban Kenya 2010.

* Client reports provider treated them “very well”

** Lines represent 95% confidence interval

DISCUSSION

This study found several indicators of family planning service quality to be significantly associated with current contraceptive use, including employing service providers who inquire into the client’s family planning preferences, assist with method selection, discuss possible side effects with clients, and treat their clients “very well”. Keeping a mix of methods on hand for clients throughout the year has a marginally significant association with contraceptive use. These aspects of method choice, information given, and client-provider relations were associated with increased likelihood of contraceptive use among the women in our sample.

Surprisingly, three aspects of family planning service delivery appear to have no association with current contraceptive use: provider competence, follow-up mechanisms, and integrated services. It is possible that the means of measuring these aspects do not sufficiently capture their true meaning. For example, just because a provider has received in-service training on family planning provision, there is no guarantee that they are more competent in service provision compared to their peers who have not received such training. Additionally, giving clients verbal instructions on when to return for continued contraceptive supplies may not impact the future behavior of clients to the same extent as additional types of reminders such as appointment cards or follow-up phone-calls, which may not be standard practice in many parts of Kenya. It may also be the case that facility managers and providers self-report higher levels of integrated services than actually take place in practice, in an attempt to exaggerate service quality [6, 28]; such misreporting may attenuate an existing relationship. It is also possible that these aspects of quality have no association with current contraceptive use.

Lastly, facility infrastructure and many aspects of client satisfaction were unrelated to contraceptive use, including privacy issues, the amount of information given, wait time, and overall satisfaction. The reason for the negative association between visual privacy and current use is unclear and may merit further investigation.

Many of the prevalence ratios observed in this study were close to the null value (1.00). However, it should be noted that, in our sample of urban Kenyan women who are not trying to become pregnant, contraceptive prevalence is 65 percent (Table 2). A prevalence ratio of 1.2, although modest as a ratio measure, equates to a 20% increase in modern contraceptive use (form 65% to 78%). Therefore, while a prevalence ratio of 1.2 is a relatively small proportion, it may represent a clinically meaningful increase in contraceptive use.

Prior to this study, the most recent multi-region assessment of family planning service quality in Kenya utilizing the Bruce framework took place in 1989 among public facilities and identified several areas of quality in need of improvement [8]. Comparisons between our findings and this previous study should be interpreted cautiously given the focus on urban areas and the inclusion of private facilities in our study and a much smaller sample of clients and use of observational data in the previous study. However, it may be worth noting that a comparison of findings2 indicates increased discussion of side effects (from 60 to 81 percent) and decreased discussion of reproductive goals (from 56 to 44 percent) and multiple methods (from 94 to 47 percent). Discussion of an appropriate return date and general client satisfaction were consistently high (above 90 percent) in both studies.

As noted in our introduction, prior multi-level studies examining the relationship between quality and contraceptive use have produced mixed results [12–18]. Some previous studies, in agreement with our results, found a positive association between quality and use. However comparisons between our findings and prior research are challenging given stark differences in region of study as well as measurement and definition of family planning service quality. Only one previous multi-level study has been conducted in sub-Saharan Africa. This prior study, conducted in Tanzania, also found an association between the information provided to clients and current contraceptive use [15]. However, this earlier study measured information by the availability of educational and promotional material, rather than discussion of side effects, method selection, or proper method use, making comparisons between the two studies problematic. Additionally, the prevalence of current contraceptive use in the sample of women in the Tanzania study was 13 percent while the prevalence within our sample of women in urban Kenya was 65 percent; therefore the same relative change in contraceptive prevalence will correspond to very different absolute differences within the two populations.

Our study identifies several modifiable aspects of family planning service quality with the potential to increase contraceptive use within a country with high fertility and high unmet need, demonstrating the large public health importance of these results. Our results suggest that, in terms of quality improvements, increases in contraceptive prevalence may be most responsive to in-service and pre-service training with an increased emphasis on the ability of providers to excel in client treatment, assist with method selection, and impart critical information on the potential side effects of selected methods. Our results also suggest the need for more specific measures of provider technical competence as well as more innovative strategies for encouraging contraceptive continuation.

The MLE project is one of the first large-scale surveys to be able to link individual and facility-level data by individual woman rather than by cluster. This allows us to assess the relationship between quality and use without the restrictive assumption that all women in the sample attend the facility most preferred by the women in their primary sampling unit or the facility in closest proximity. To our knowledge, no other population-based studies have been able to link individual women to their current health facility, highlighting the novelty of this research. The MLE project is also the first large scale survey to focus exclusively on urban populations in developing countries, allowing for an in-depth investigation of this rapidly growing population. Lastly, this is one of only a handful of studies to consider all six aspects of quality as well as facility infrastructure and is the first comprehensive multi-region situation analysis conducted in Kenya since the early 1990s.

There are some limitations to this study which warrant discussion. Approximately 30 percent of the eligible women could not be linked to a facility at which the MLE project collected baseline facility-level data and therefore had to be excluded from the analysis; these exclusions suggest some bias in the MLE/Tupange study selection of facilities and caution should be used when generalizing results to unmarried and nulliparous women.

Additionally, aggregated indicators at the facility level may not represent the experience of an individual client; for example, just because the majority of provider or client self-reports suggest a facility provides poor quality of care, it is not necessarily the case that all women attending this same facility are subjected to low quality services, especially in facilities with multiple providers. Similarly, it is possible that provider performance varies from client to client, depending on numerous factors. For example, the same provider may typically discuss side-effects with their clients but may fail to do so on days when they experience a higher volume of clients.

Some women who did not report seeking family planning services were linked to a facility where they reported seeking other health care services, possibly leading to misclassification of their exposure status: these women may not have been exposed to the facility’s quality of family planning care. However, as seen in the results section, integration of family planning and other services is widespread among the clinics in this area. Further, the assumption that a woman is impacted by quality of care at a clinic she is known to have attended, even if she is not known to have received family planning services there, is stronger than the common assumption in prior similar studies that a woman is impacted by quality of care at proximal facilities which she is not known to have visited.

It is possible that providers may fail to provide an accurate report of their service delivery behaviors in an effort to portray their performance in a positive light. This could be the result of social desirability bias, whereby the respondent wants to offer the interviewer a pleasing answer. Similarly, client responses may be influenced by a desire to please the interviewer, protect themselves from retribution from facility staff, or by a cultural reluctance to provide negative information.

Also of note, given the large number of quality variables examined each for their association with contraceptive use, we would expect one or two spuriously significant results at an alpha level of five percent. Lastly, for some women, data on the exposure status were collected up to a year after data were collected on the outcome of current contraceptive use. However, we don’t expect that quality changed meaningfully during this time period and therefore should not have substantially biased our results.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this analysis support the concept of promoting facility-level improvements in the delivery of contraceptive services especially with respect to: assistance with method selection, counseling on contraceptive side effects, and client treatment. Increased attention around the importance of positive and informative interactions between providers and clients are potential strategies for increasing contraceptive use in this region of high unmet need.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant awarded to the Carolina Population Center (CPC) at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. We are grateful to CPC (R24 HD050924) for general support. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CPC or the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Appendix

Table A1.

Indicators that measure quality of care, corresponding data collection instrument, and coding scheme

| Element of Quality | Indicator | Survey Tool | Coding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Choice of Methods | Does this facility provide the following FP methods? Is the method currently available? Has this facility had a stock-out of the method in the last one year? |

Facility Audit | Coded as continuous (range 0–12) Coded as continuous (range 0-8) Coded as continuous (range 0-8) |

| Do you provide information about different methods? Do you discuss the client’s family planning preferences? |

Provider Interview | Coded as binary* | |

| Did your provider provide information about different FP methods? Did your provider ask about your method of choice? |

Client Interview | Coded as continuous** | |

| Information Given to User | Do you help a client select a suitable method? Do you explain the way to use the selected method? Do you explain the side effects? Do you explain specific medical reasons to return? |

Provider Interview | Coded as binary* |

| Did your provider help you select a method? Did your provider explain how to use the method? Did your provider talk about possible side effects? Did your provider tell you what to do if you have any problems? |

Client Interview | Coded as continuous** | |

| Provider Competence | Have you received any in-service training on providing methods of family planning? | Provider Interview | Coded as binary* |

| Client-Provider Relations | Do you identify reproductive goals of the client? | Provider Interview | Coded as binary* |

| Did your provider ask your reproductive goal? During your visit, how were you treated by the provider? During your visit, how were you treated by the other staff? Did you feel comfortable to ask questions during this visit? Did the provider ask you if you had any questions? Did the provider answer all of your questions? |

Client Interview | Coded as continuous** | |

| Continuity Mechanism | Did your provider tell you when to return for follow-up? | Client Interview | Coded as continuous** |

| Appropriate Constellation of Services | When a woman who has come in for child health services is also interested in receiving family planning counseling, does she always receive it on the same day? When a woman who has come in for postpartum services is also interested in receiving family planning counseling, does she always receive it on the same day? When a woman who has come in for HIV services is also interested in receiving family planning counseling, does she always receive it on the same day? |

Facility Audit | Coded as binary |

| During child immunization/child growth monitoring, do you provide information about FP routinely? During post-natal care visits, do you provide information about FP routinely? While providing HIV-related services (HIV/AIDS management, PMTCT, and/or VCT) to women and men, do you provide information on FP routinely? |

Provider Interview | Coded as binary* |

For each quality indicator from the provider interview, the proportion of providers at each facility responding affirmatively was calculated, and clinics were then dichotomized as having a provider proportion of positive responses at/above versus below the sample-wide proportion for that indicator.

For each quality indicator from the client interview, the proportion of clients at each facility responding affirmatively was calculated. Client interview variables were entered into the model as continuous variables and were multiplied by 4 to range from 0–4, so that estimated prevalence ratios reflect the change in contraceptive prevalence associated with a 25% increase in that indicator.

Footnotes

This is an early draft of an article published in June 2015 in International Perspectives in Sexual and Reproductive Health. Complete citation information for the final version of the paper, as published in the on-line edition of International Perspectives in Sexual and Reproductive Health, is available on the journal’s website at http://www.guttmacher.org/journals/toc/ipsrh4003toc.html.

A mix of methods is defined as at least one long acting or permanent method, one shorter-acting method, and one barrier method.

The prior study used only third-party observational data; we compare this to provider self-reports in our study. Unfortunately the prior study did not use client or provider interview data and our study did not use observational data; therefore a direct comparison is not possible.

References

- 1.Population Reference Bureau. Family Planning Worldwide 2013 Datasheet. 2013 < http://www.prb.org/pdf13/family-planning-2013-datasheet_eng.pdf>, accessed May 20, 2014.

- 2.Bongaarts J, Bruce J. The causes of unmet need for contraception and the social content of services. Studies in Family Planning. 1995;26(2):57–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardee K, Gould BJ. A Process for Quality Improvement In Family Planning Services. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1993;19(4):147–152. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain AK, Bruce J, Kumar S. Quality of services, programme efforts and fertility reduction. In: Phillips JF, Ross JA, editors. Family planning programmes and fertility. Clarendon Press; Oxford, England: 1992. pp. 202–221. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kols AJ, Sherman JE. Family planning programs: improving quality. Population reports Series J, Family planning programs. 1998;(47):1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simmons R, Elias C. The study of client-provider interactions: a review of methodological issues. Studies in Family Planning. 1994;25(1):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bongaarts J. Can family planning programs reduce high desired family size in sub-saharan Africa? International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2011;37(4):209–216. doi: 10.1363/3720911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The World Bank. World Development Indicators. 2014 < http://databank.worldbank.org/data/views/variableselection/selectvariables.aspx?source=world-development-indicators> accessed May 20, 2014.

- 9.The Measurement Learning & Evaluation Project website. Kenya: 2012. < https://www.urbanreproductivehealth.org/projects/kenya> accessed January 12, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller RA, et al. The Situation Analysis Study of the family planning program in Kenya. Studies in Family Planning. 1991;22(3):131–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mensch B, et al. Family Planning in Nairobi: A Situation Analysis of the City Commission Clinics. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1994;20:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ali MM. Quality of care and contraceptive pill discontinuation in rural Egypt. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2001;33(2):161–172. doi: 10.1017/s0021932001001614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnani RJ, et al. The impact of the family planning supply environment on contraceptive intentions and use in Morocco. Studies in Family Planning. 1999;30(2):120–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.1999.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mensch B, Arends-Kuenning M, Jain AK. The impact of the quality of family planning services on contraceptive use in Peru. Studies in Family Planning. 1996;27(2):59–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arends-Kuenning M, Kessy FL. The impact of demand factors, quality of care and access to facilities on contraceptive use in Tanzania. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2007;39(1):1–26. doi: 10.1017/S0021932005001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gubhaju B. Barriers to sustained use of contraception in Nepal: quality of care, socioeconomic status, and method-related factors. Biodemography and Social Biology. 2009;55(1):52–70. doi: 10.1080/19485560903054671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong R, Montana L, Mishra V. Family planning services quality as a determinant of use of IUD in Egypt. BMC Health Services Research. 2006;6:79–87. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.RamaRao S, et al. The link between quality of care and contraceptive use. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2003;29(2):76–83. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.29.076.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arends-Kuenning M, Mensch B, Garate MR. Comparing the Peru service availability module and situation analysis. Studies in Family Planning. 1996;27(1):44–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.United Nations. World Urbanisation Prospects: The 2005 Revision. Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.eHealth-Kenya Facilities. Master Facilities List (MFL) 2014 < http://www.ehealth.or.ke/facilities/> accessed February 18, 2014.

- 22.Bruce J. Fundamental elements of the quality of care: a simple framework. Studies in Family Planning. 1990;21(2):61–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain AK. Fertility reduction and the quality of family planning services. Studies in Family Planning. 1989;20(1):1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain A, Bruce J, Kumar S. Quality of services, programme efforts and fertility reduction. In: Phillips JF, Ross JA, editors. Family planning programmes and fertility. Clarendon Press; Oxford, England: 1992. pp. 202–21. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuoane M, Madise NJ, Diamond I. Provision of family planning services in Lesotho. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2004;30(2):77–86. doi: 10.1363/3007704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huezo C, Diaz S. Quality of care in family planning: clients’ rights and providers’ needs. Advances in Contraception. 1993;9(2):129–39. doi: 10.1007/BF01990143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.RamaRao S, Mohanam R. The quality of family planning programs: concepts, measurements, interventions, and effects. Studies in Family Planning. 2003;34(4):227–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2003.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tumlinson K, et al. Accuracy of Standard Measures of Family Planning Service Quality: Findings from the Simulated Client Method. Studies in Family Planning. 2014;45(4) doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00007.x. TBD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]