Abstract

Mild traumatic brain injury, often referred to as concussion, is a common, potentially debilitating, and costly condition. One of the main challenges in diagnosing and managing concussion is that there is not currently an objective test to determine the presence of a concussion and to guide return-to-play decisions for athletes. Traditional neuroimaging tests, such as brain magnetic resonance imaging, are normal in concussion, and therefore diagnosis and management are guided by reported symptoms. Some athletes will under-report symptoms to accelerate their return-to-play and others will over-report symptoms out of fear of further injury or misinterpretation of underlying conditions, such as migraine headache. Therefore, an objective measure is needed to assist in several facets of concussion management. Limited data in animal and human testing indicates that intracranial pressure increases slightly and cerebrovascular reactivity (the ability of the cerebral arteries to auto-regulate in response to changes in carbon dioxide) decreases slightly following mild traumatic brain injury. We hypothesize that a combination of ultrasonographic measurements (optic nerve sheath diameter and transcranial Doppler assessment of cerebrovascular reactivity) into a single index will allow for an accurate and non-invasive measurement of intracranial pressure and cerebrovascular reactivity, and this index will be clinically relevant and useful for guiding concussion diagnosis and management. Ultrasound is an ideal modality for the evaluation of concussion because it is portable (allowing for evaluation in many settings, such as on the playing field or in a combat zone), radiation-free (making repeat scans safe), and relatively inexpensive (resulting in nearly universal availability). This paper reviews the literature supporting our hypothesis that an ultrasonographic index can assist in the diagnosis and management of concussion, and it also presents limited data regarding the initial use of this index in healthy controls.

Keywords: Concussion, optic nerve sheath diameter, transcranial Doppler, intracranial pressure, cerebrovascular reactivity

INTRODUCTION

Mild traumatic brain injury (referred to as “concussion” throughout the rest of this article) affects between 1.6 and 3.8 million athletes in the United States each year, and military personnel and other civilians are also affected at high rates. (1–3) It is estimated that direct and indirect costs related to concussion totaled $12 billion in the United States in 2000. (4) Concussion is defined as a blow to the head that causes a brief loss or alteration of consciousness or post-traumatic amnesia. (2) There are many issues related to concussion that are of importance, including prevention and treatment, but clinicians who care for patients with concussion realize that some of the most pressing issues involve diagnosis and return-to-play. (5,6) The lack of objective biomarkers of concussion and reliance upon reported symptoms can result in inaccurate diagnoses and uncertainty regarding timing of return-to-play. Athletes might minimize symptoms to avoid a concussion diagnosis and accelerate return-to-play, which may increase the risk of the devastating second impact syndrome and the development of long-term conditions such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy. (7,8) Conversely, athletes may overemphasize symptoms, because of fear, misinterpretation of previously existing symptoms such as migraine headache, or even secondary gain. While this is perhaps less dangerous than returning to play too soon, it may be associated with increased anxiety and depression in athletes. (9)

Currently, athletes are diagnosed with concussion following biomechanically induced trauma that results in alterations of memory and orientation, and they should be cleared to return to play only when symptoms have resolved. (10) Commonly used tools to assess concussion include the post-concussion symptom scale, graded symptom checklist, standardized assessment of concussion, balance error scoring system, and combinations of these tools such as the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool 2 (SCAT2) and the National Football League Sideline SCAT. (11) These tools are limited by their subjectivity and moderate accuracy. (10) Recent efforts have been made to identify biomarkers of concussion, including the use of serum and imaging markers. (12,13)

Results of routine intracranial imaging modalities, such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are typically normal in concussion, though very subtle changes can be detected in a subset of patients using specialized MRI techniques. (13) While normal imaging is helpful in excluding major intracranial pathology in concussion, it is of limited utility otherwise in the guidance of clinical care and decision-making. Although these anatomic imaging modalities may be normal, it is known that subtle pathophysiologic changes not detected by routine imaging occur secondary to microscopic axonal injury in the brains of those with concussion. (14) In addition, preliminary studies show subtle changes in intracranial pressure and blood flow in concussion, (15,16) which has led us to consider that a non-invasive measure of intracranial pressure and blood flow may be a powerful tool in the evaluation of concussion. Since ultrasound is non-invasive, radiation-free, and can measure both intracranial pressure (through the assessment of optic nerve sheath diameter) and blood flow (through transcranial Doppler assessment of the ability of the cerebral arteries to auto-regulate in response to changes in carbon dioxide, termed “cerebrovascular reactivity”), it is an ideal imaging modality and was a critical piece in the generation of our hypothesis.

HYPOTHESIS

We hypothesize that individuals with concussion will have a subtle increase in intracranial pressure (detectable by an increase in optic nerve sheath diameter) and a decrease in cerebrovascular reactivity (detectable by a decrease in cerebrovascular reactivity to breath holding during transcranial Doppler), and a combination of these parameters into a single index will create an accurate and responsive biomarker of concussion.

EVALUATION OF THE HYPOTHESIS

Though the data are not fully developed, there is evidence in both animal models and humans that subtle increases in intracranial pressure and decreases in cerebrovascular reactivity occur following mild traumatic brain injury, and both of these findings are discussed below. Additionally, the generation of a single index from two ultrasonographic parameters is outlined below, including pilot data from a small sample of healthy young adults.

Increased Intracranial Pressure

In 2012, Bolouri and colleagues reported their results regarding intracranial pressure in a Wistar rat model of concussion in which the rats were fitted with aluminum helmets. (15) Following simulated concussion, the mean intracranial pressure increased from a baseline of approximately 6 mmHg to a peak of approximately 14 mmHg at 10 hours after the simulated concussion. Intracranial pressure returned to baseline within 7 days of the simulated concussion.

In humans, it is more difficult to demonstrate intracranial pressure increases following concussion because invasive monitoring is not routinely performed. However, evidence exists supporting the occurrence of increased intracranial pressure in humans. First, intracranial pressure clearly increases after moderate or severe TBI, as detected by invasive intracranial monitoring in clinical settings, and since concussion is the mild part of the traumatic brain injury spectrum it is assumed that intracranial pressure increases also occur to some degree in concussion. (17) Second, Pomschar and colleagues reported in 2013 that MRI measurements of venous drainage and cerebrospinal fluid flow, as assessed via cine imaging, allow for measurements of brain compliance and intracranial pressure. (18) Using this technique, 15 subjects with concussion had a mean estimated intracranial pressure of 12.5 mmHg compared to an intracranial pressure of 8.8 mmHg in 15 controls (p < 0.0007).

Over the past 20 years, a large number of studies have reported that the diameter of the optic nerve sheath, measured 3 mm behind the posterior portion of the globe, correlates closely with intracranial pressure. (19,20) This measurement can be easily and rapidly obtained using a moderate to high frequency linear array ultrasound transducer (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A 12 MHz linear array transducer was used to obtain this image, which shows the globe and the optic nerve (marked by calipers). The “+” calipers are used to mark 3 mm deep to the posterior globe and the “x” calipers mark the width of the optic nerve sheath.

Decreased Cerebrovascular Reactivity

Whereas measurements of intracranial pressure in humans historically involve invasive monitoring or sampling, measurements of intracranial blood flow historically have been accomplished using non-invasive imaging techniques, with several decades of reports supporting the use of transcranial Doppler. Therefore, there are many more human studies of the intracranial vasculature in concussion than there are studies of intracranial pressure. Several studies have assessed proximal middle cerebral artery (MCA) blood flow associated with concussion, with some showing an increased velocity compared to controls and others not showing a significant increase. These studies are limited by study size and timing of transcranial Doppler relative to concussion. (16,21) More universal agreement has been reached regarding a decrease in cerebrovascular reactivity following concussion. Breath holding in healthy controls leads to increased carbon dioxide and an autoregulatory increase in MCA velocity, but in those with concussion this cerebrovascular reactivity is decreased as early as the day of concussion and may quickly resolve or persist for days. (16,21–23) The cause of the decreased cerebrovascular reactivity following concussion is unknown, but proposed mechanisms include an alteration in the local chemical environment of the cerebral vessels and a more systemic loss of cardiovascular regulation. (22)

As with optic nerve sheath diameter measurement, transcranial Doppler measurement of MCA blood flow before and after breath-holding is relatively easily and rapidly obtained (Figure 2). Several methods can be used to challenge cerebrovascular reactivity, including inhaled carbon dioxide, oral acetazolamide, hyperventilation, and breath-holding. Breath-holding is simple yet accurate and reproducible, (22) which is why it is the method of choice in the index we propose. The breath-holding index is calculated using the following formula:

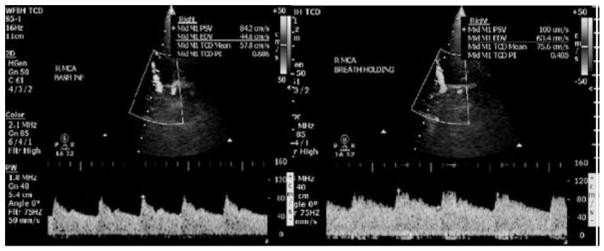

Figure 2.

On the left is the proximal right MCA transcranial Doppler at baseline (mean velocity 57.8 cm/s), and on the right is at the end of 30 seconds of breath holding (mean velocity 75.6 cm/s). This is a 31% increase and can be visualized as the taller Doppler waveforms on the right. The vessel is outlined by the white trapezoidal-shaped window.

Creation of the Rapid Ultrasonographic Brain Index (RUBI)

It is hypothesized that a combination of ultrasonographic measures of intracranial pressure and cerebrovascular reactivity into a single index will create an accurate and responsive objective measure of concussion, and we term this the rapid ultrasonographic brain index (RUBI). The following formula will be used to calculate the RUBI:

This formula employs an expected mean optic nerve sheath diameter of 4.0 mm and standard deviation of 0.5 mm, which are based on data obtained from several populations of healthy controls. (19,20) It also uses an expected mean breath holding index of 1.8 with a standard deviation of 0.5, which too are based on values obtained from healthy controls. (24,25)

Pilot Data

To initiate an investigation into the RUBI as a biomarker of concussion, we designed a pilot study to assess the RUBI in five healthy young adults. Prior to initiation of the study, it was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and all participants signed written informed consent. Five young adults without underlying medical conditions were recruited from students and personnel at our medical center. Each underwent measurement of the optic nerve sheath and MCA velocity bilaterally, before and after 30 seconds of breath-holding, and this was conducted at 8:00 AM, 12:00 PM, and 5:00 PM in each individual to determine if time of day had any effect on the RUBI calculation.

The mean age of the participants was 25 years old and mean BMI was 22.0. The mean optic nerve sheath diameter (calculated by averaging the bilateral results in each participant), mean breath-holding index (calculated by averaging the bilateral breath-holding indices in each participant), and mean RUBI at each collection time are reported in Table 1. For each collection time the mean RUBI was 0.01, indicating that time-of-day may not affect the RUBI and that our choice of mean values in the RUBI formula may be appropriate, as healthy controls would be expected to have RUBI values near 0. However, it should be noted that these data are preliminary and further investigation is needed to assess the RUBI in healthy controls.

Table 1.

The data in this table were collected from five healthy volunteers, with a mean age of 25 and BMI of 22.0.

| Time of Day | Mean Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter (mm) | Mean Breath-holding Index | Mean Rapid Ultrasonographic Brain Index (RUBI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8:00 AM | 3.28 | 1.13 | 0.01 |

| 12:00 PM | 3.35 | 1.12 | 0.01 |

| 5:00 PM | 3.27 | 1.03 | 0.01 |

CONSEQUENCES OF THE HYPOTHESIS

The hypothesis that individuals with concussion will have a subtle increase in intracranial pressure and decrease in cerebrovascular reactivity, and a combination of these parameters into a single index termed the RUBI will create an accurate and responsive biomarker of concussion is supported by research in animal models and humans with concussion. However, further investigation is needed to fully evaluate this potential biomarker. Initial research should focus on healthy controls, and the effects that time-of-day, age, underlying medical conditions, and recent exercise may have on the RUBI. This would allow for the formula to be optimized, and for the identification of any variables that may influence the RUBI.

Once studied thoroughly in healthy controls, the next step would be to obtain baseline RUBI measurements in individuals at risk for concussion, such as high school and college athletes in contact sports. Baseline RUBIs could be compared to the RUBI immediately following a concussion and 24, 72, and 192 hours after the concussion to determine post-concussive RUBI changes over time. This would be correlated with concussion scales currently in use to determine the accuracy of the RUBI for diagnosis and determining a return to baseline to guide safe return-to-play.

Although the combination of ultrasonographic parameters into the RUBI is a promising tool for studying concussion, there are potential drawbacks. First, ultrasound is operator-dependent, and therefore one or both of the parameters may lack intra- or inter-rater reliability. This is testable, and should be one focus of the initial investigations that occurs with this technique. If not reliable, changes in technique or more extensive training would be likely to ameliorate this potential problem. Second, it is possible that changes in intracranial pressure and cerebrovascular reactivity will occur, but that the ultrasonographic techniques described above will not be sensitive enough to detect these changes. If this occurs, further investigation into ultrasonographic imaging techniques will need to be conducted, which may include adding further parameters or altering devices or techniques. Third, it is possible that intracranial pressure and/or cerebrovascular reactivity will not reliably change following concussion, despite the promising information that has been obtained in animal models and humans. While unlikely, if this finding is detected through investigations using the RUBI in healthy controls and individuals with concussion, then this will, at the very least, advance understanding of the pathophysiology of concussion.

We hypothesize that the RUBI will be sensitive, specific, and responsive as a biomarker of concussion, and therefore the RUBI could be implemented as a standard tool to guide concussion care. Since ultrasound is non-invasive, involves no radiation, can be conducted rapidly and in many settings, and is nearly universally available, it has the potential to positively impact concussion care for athletes of all ages and skill levels, as well as those that suffer concussion in non-sports settings.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: No funding was received for this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Langlois JA, Rutland-Brown W, Wald MM. The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006 Oct;21(5):375–8. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200609000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilk JE, Herrell RK, Wynn GH, Riviere LA, Hoge CW. Mild traumatic brain injury (concussion), posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in U.S. soldiers involved in combat deployments: association with postdeployment symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2012 Apr;74(3):249–57. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318244c604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaloshnja E, Miller T, Langlois JA, Selassie AW. Prevalence of long-term disability from traumatic brain injury in the civilian population of the United States, 2005. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2008 Dec;23(6):394–400. doi: 10.1097/01.HTR.0000341435.52004.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkelstein E. The incidence and economic burden of injuries in the United States. Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray IR, Murray AD, Robson J. Sports concussion: time for a culture change. Clin J Sport Med Off J Can Acad Sport Med. 2015 Mar;25(2):75–7. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levin HS, Diaz-Arrastia RR. Diagnosis, prognosis, and clinical management of mild traumatic brain injury. Lancet Neurol. 2015 May;14(5):506–17. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinstein E, Turner M, Kuzma BB, Feuer H. Second impact syndrome in football: new imaging and insights into a rare and devastating condition. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013 Mar;11(3):331–4. doi: 10.3171/2012.11.PEDS12343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stern RA, Riley DO, Daneshvar DH, Nowinski CJ, Cantu RC, McKee AC. Long-term consequences of repetitive brain trauma: chronic traumatic encephalopathy. PM R. 2011 Oct;3(10 Suppl 2):S460–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harmon KG, Drezner J, Gammons M, Guskiewicz K, Halstead M, Herring S, et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sport. Clin J Sport Med Off J Can Acad Sport Med. 2013 Jan;23(1):1–18. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31827f5f93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giza CC, Kutcher JS, Ashwal S, Barth J, Getchius TSD, Gioia GA, et al. Summary of evidence-based guideline update: evaluation and management of concussion in sports: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013 Jun 11;80(24):2250–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828d57dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Johnston K, Dvorak J, Aubry M, Molloy M, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport - the Third International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2008. Phys Sportsmed. 2009 Jun;37(2):141–59. doi: 10.3810/psm.2009.06.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shan R, Szmydynger-Chodobska J, Warren OU, Zink BJ, Mohammad F, Chodobski A. A New Panel of Blood Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury/Concussion in Adults. J Neurotrauma. 2015 Mar 20; doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuh EL, Mukherjee P, Lingsma HF, Yue JK, Ferguson AR, Gordon WA, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging improves 3-month outcome prediction in mild traumatic brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2013 Feb;73(2):224–35. doi: 10.1002/ana.23783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barkhoudarian G, Hovda DA, Giza CC. The molecular pathophysiology of concussive brain injury. Clin Sports Med. 2011 Jan;30(1):33–48. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2010.09.001. vii – iii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolouri H, Säljö A, Viano DC, Hamberger A. Animal model for sport-related concussion; ICP and cognitive function. Acta Neurol Scand. 2012 Apr;125(4):241–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2011.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jünger EC, Newell DW, Grant GA, Avellino AM, Ghatan S, Douville CM, et al. Cerebral autoregulation following minor head injury. J Neurosurg. 1997 Mar;86(3):425–32. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.3.0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heegaard W, Biros M. Traumatic brain injury. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007 Aug;25(3):655–78. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pomschar A, Koerte I, Lee S, Laubender RP, Straube A, Heinen F, et al. MRI evidence for altered venous drainage and intracranial compliance in mild traumatic brain injury. PloS One. 2013;8(2):e55447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helmke K, Hansen HC. Fundamentals of transorbital sonographic evaluation of optic nerve sheath expansion under intracranial hypertension. I. Experimental study. Pediatr Radiol. 1996 Oct;26(10):701–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01383383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimberly HH, Shah S, Marill K, Noble V. Correlation of optic nerve sheath diameter with direct measurement of intracranial pressure. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2008 Feb;15(2):201–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Len TK, Neary JP, Asmundson GJG, Candow DG, Goodman DG, Bjornson B, et al. Serial monitoring of CO2 reactivity following sport concussion using hypocapnia and hypercapnia. Brain Inj. 2013;27(3):346–53. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2012.743185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Len TK, Neary JP, Asmundson GJG, Goodman DG, Bjornson B, Bhambhani YN. Cerebrovascular reactivity impairment after sport-induced concussion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011 Dec;43(12):2241–8. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182249539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becelewski J, Pierzchała K. Cerebrovascular reactivity in patients with mild head injury. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2003 Apr;37(2):339–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bago-Rozanković P, Lovrencić-Huzjan A, Strineka M, Basić S, Demarin V. Assessment of breath holding index during orthostasis. Acta Clin Croat. 2009 Sep;48(3):299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lepur D, Kutleša M, Baršić B. Prospective observational cohort study of cerebrovascular CO2 reactivity in patients with inflammatory CNS diseases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol. 2011 Aug;30(8):989–96. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1184-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]