Abstract

Whether you are an avid reader of the Book Thief or a fan of the Blue Oyster Cult, you know that messing with me is serious business. Be warned, that if you want to outwit me, you better come armed with the ability to predict your future.

The Grim Reaper

Severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH) has a short term mortality rate that rivals the most feared of human maladies over centuries including the current day calamities of pancreatic cancer, AIDS, and even sepsis syndrome. AH presents as an acute deterioration of liver function in patients with active and excessive alcohol consumption. It manifests as jaundice, fever, hepatomegaly, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy with aspartate aminotransferase exceeding serum alanine aminotransferase, along with elevated leukocyte count. These parameters have helped to inform a variety of scoring systems that are used to determine severity and predict mortality. Recently, liver histology has also been used to predict disease severity but comes with the drawback that it is invasive and expensive.1 The non-invasive severity scoring systems are comparably effective in predicting mortality with Maddrey discriminant function (mDF) and Model for Endstage Liver Disease (MELD) score most widely utilized to determine the need for pharmacotherapy. The models are best characterized for risk benefit analysis for use of corticosteroids. Unfortunately, these models are associated with the deficiency that even patients below the cut-point dictating therapy still have significant risk of death.

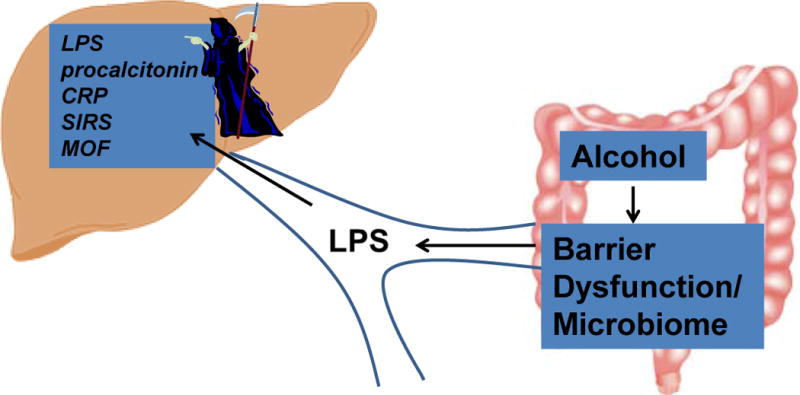

Research during the last several decades has led to a better understanding of the mechanisms of AH especially the key role of inflammation. In the canonical pathway, alcohol disrupts gut barrier function and alters resident microbiota which leads to elevated delivery of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to the portal circulation and resident liver cells. LPS and other bacterial products act through Toll like Receptors (TLRs) residing on multiple liver cell types to induce Kupffer cell activation. Activated Kupffer cells in turn, secrete interleukin (IL)-1β and other chemokines to stimulate the characteristic neutrophil infiltration observed in histological specimens of patients with severe AH.2 Can we utilize these pathophysiological mechanisms to better inform our predictive capacity for AH severity?

The Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) was initially defined by the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and Society of critical Care Medicine (SCCM).3 as the clinical manifestation of sepsis. The clinical features of SIRS are fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, and leukocytosis or leukopenia. SIRS was subsequently recognized as a marker of ongoing inflammation and noted in patients with acute liver failure as well as in patients with acute on chronic liver failure. Whereas SIRS may be precipitated by sepsis, a significant proportion of patients with SIRS may not have a documented source of infection and SIRS parameters may not be always helpful to identify risk of death in patient with severe sepsis.4 Irrespective of the precipitating event, SIRS triggers a cascade of events that culminate in multi-system organ failure.5 Our current knowledge of SIRS focuses on dysregulated and uncontrolled inflammatory response followed by a compensatory anti-inflammatory response that leads to increased susceptibility to infection and multiple organ failure (MOF); the risk of mortality increases with increasing presence of these SIRS parameters.

AH is marked by both an excessive systemic immune reaction and an impaired antibacterial immune response. Patients with AH have compromised immune function through chronic endotoxin-driven pathways targeting immune effector cells and that result in a reduction of interferon-γ/IL-10.6 Thus, the inflammatory/immune response in AH may paradoxically be counterproductive and predispose to infection.

The optimal strategy in patients with severe AH would be to identify those at risk for MOF and prevent MOF allowing improved short term survival. At present, corticosteroids and pentoxifylline are the most widely used drugs in the treatment of severe AH (with recent studies increasingly favoring the former) but they provide survival benefit in only 50% of patients.7

In this issue of Hepatology, Michelena et al8 present predictors of MOF and risk of death in severe AH patients. The authors identified SIRS as being associated with development of acute kidney injury (AKI), MOF, and mortality. Data were obtained from 162 severe AH patients with biopsy-proven, severe AH defined as Maddrey Discriminant Function (MDF) > 329 and/or ABIC score > 6.7110 admitted to the Liver Unit in Barcelona. Overall 90-day mortality was significantly higher among patients with SIRS at admission. Patients with SIRS had a higher incidence of MOF during hospitalization than patients without SIRS independent of the degree of liver dysfunction and the Lille score.11 Thus SIRS predicts mortality in AH.

In addition to the specific role of SIRS, the authors also identified serum biomarkers capable of predicting mortality and differentiating SIRS in the presence of infection from SIRS without infection. Importantly, the authors found procalcitonin, LPS and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) were associated with short term 90-day mortality in patients with severe AH. In subgroup analysis, serum levels of LPS could predict the development of MOF during hospitalization and also correlated with the severity of AH. Moreover, LPS at admission also predicted the response to corticosteroids suggesting that its measurement could presage non-responders to corticosteroids therapy. Procalcitonin levels were higher in patients with infection-associated SIRS than in patients with SIRS without infection. The compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome which limits inflammation but leads to immune paralysis and increased susceptibility to infection was not addressed in this study, but would be of interest to further refine this complex profile.

Pharmacotherapy is indicated for patients with severe AH, but it is essential that the benefits of therapy outweigh potential adverse effects. Therefore, treatment has to be individualized. It is important to know who will benefit from steroid therapy but also to determine which patient has infection, and in whom all treatment is likely to be futile. Early identification of infection and non-responders to corticosteroids treatment are therefore important strategies for AH management. While SIRS was demonstrated as risk of development of MOF and death, it was not always associated with infection. Indeed, infection is difficult to recognize and SIRS criteria cannot reliably differentiate sepsis from non-infectious SIRS. Identification of LPS as a potential biomarker for mortality and failure of corticosteroid therapy (which fits nicely with pathophysiological paradigms) is appealing but this message should be confirmed in prospective and independent studies. Another important question that arises is whether it is SIRS or infection that leads to increased mortality since increased LPS may not equate with active infection.

Although many aspects of SIRS, the compensatory anti-inflammatory response, and organ failure in AH remain unclear, this paper is a step in the right direction in our quest to develop better predictors of mortality and treatment response in AH. Continued innovation and translation of the knowledge from science to practice will help predict which patients who suffer from this lethal complication of alcoholic liver disease will die and conversely, which have a chance to outwit the Grim Reaper.

Figure 1. Alcoholic hepatitis: SIRS, MOF, infection, and the Grim Reaper.

Chronic alcohol consumption increases gut permeability and changes gut microbial flora resulting in high circulating lipopolysaccharide (LPS) which reaches the liver and the systemic circulation via the portal system. LPS stimulates the acute inflammatory response that manifests clinically as SIRS and can be detected by measuring LPS, C-reactive protein (CRP), and procalcitonin. SIRS is associated with infection in some cases and predicts mortality in AH in part due to “immune paralysis” (not shown) and MOF.

Acknowledgments

This article received funding from NIH through grant number U01 AA021788

References

- 1.Altamirano J, Miquel R, Katoonizadeh A, Abraldes JG, Duarte-Rojo A, Louvet A, Augustin S, Mookerjee RP, Michelena J, Smyrk TC, Buob D, Leteurtre E, Rincon D, Ruiz P, Garcia-Pagan JC, Guerrero-Marquez C, Jones PD, Barritt ASt, Arroyo V, Bruguera M, Banares R, Gines P, Caballeria J, Roskams T, Nevens F, Jalan R, Mathurin P, Shah VH, Bataller R. A histologic scoring system for prognosis of patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1231–9. e1–6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altamirano J, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new targets for therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:491–501. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaukonen K-M, Bailey M, Pilcher D, Cooper DJ, Bellomo R. Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome Criteria in Defining Severe Sepsis. New England Journal of Medicine. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415236. 0: null. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369:840–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markwick LJL, Riva A, Ryan JM, Cooksley H, Palma E, Tranah TH, Manakkat Vijay GK, Vergis N, Thursz M, Evans A, Wright G, Tarff S, O’Grady J, Williams R, Shawcross DL, Chokshi S. Blockade of PD1 and TIM3 Restores Innate and Adaptive Immunity in Patients With Acute Alcoholic Hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 148:590–602. e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singal AK, Kamath PS, Gores GJ, Shah VH. Alcoholic Hepatitis: Current Challenges and Future Directions. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014;12:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michelena J. Systemic Inflammatory response and serum lipopolysaccharide levels predict multiple organ failure and death in alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 2015 doi: 10.1002/hep.27779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maddrey WC, Boitnott JK, Bedine MS, Weber FL, Mezey E, White RI. CORTICOSTEROID-THERAPY OF ALCOHOLIC HEPATITIS. Gastroenterology. 1978;75:193–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dominguez M, Rincon D, Abraldes JG, Miquel R, Colmenero J, Bellot P, Garcia-Pagan JC, Fernandez R, Moreno M, Banares R, Arroyo V, Caballeria J, Gines P, Bataller R. A new scoring system for prognostic stratification of patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2747–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathurin P, O’Grady J, Carithers RL, Phillips M, Louvet A, Mendenhall CL, Ramond MJ, Naveau S, Maddrey WC, Morgan TR. Corticosteroids improve short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis: meta-analysis of individual patient data. Gut. 2011;60:255–60. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]