Abstract

Introduction

Patients with stage II/III rectal cancers are treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiation and surgical resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy (CT) per practice guidelines. It is unclear whether adjuvant CT provides survival benefit, and the purpose of this study was to measure outcomes in patients who did and did not receive adjuvant CT.

Materials and Methods

We used a prospectively collected database for patients treated at The Ohio State University, and analyzed overall survival (OS), time to recurrence, patient characteristics, tumor features, and treatments. Survival curves were estimated using Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Age was compared using the Wilcoxon test, and other categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher exact test.

Results

Between August 2005 and July 2011, 110 patients were identified and 71 patients had received adjuvant CT. There was no significant difference in sex, race, pathologic tumor stage, and pathologic complete response between the 2 patient groups. Although patient characteristics showed a difference in age (median age 54.3 vs. 62 y, P = 0.01) and advanced pathologic nodal status (43% vs. 19%, P = 0.02), there was a significant difference in OS. Median OS was 72.6 months with CT versus 36.4 months without CT (P = 0.0003). Median time to recurrence has not yet been reached.

Conclusions

In this retrospective analysis, adjuvant CT was associated with a longer OS despite more advanced pathologic nodal staging. Prospective randomized studies are warranted to determine whether adjuvant CT provides a survival benefit for patients across the spectrum of stage II and III rectal cancer.

Keywords: rectal cancer, adjuvant chemotherapy, survival, neo-adjuvant chemoradiation

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common malignancies in the world. In 2011, approximately 39,870 new cases of rectal cancer were diagnosed in the United States, with a significant proportion having locally advanced disease.1 In patients with locally advanced rectal cancer, a surgical approach with a total mesorectal excision is the treatment of choice. To improve the rate of margin-negative resection, sphincter preservation, and to decrease the rate of local recurrence and prolong overall survival (OS), patients with locally advanced, clinically resectable (T3/T4 and/or positive nodal status) rectal cancer are recommended to receive concurrent chemoradiation (CRT). Studies have shown that neo-adjuvant CRT significantly increased local control with decreased rates of local recurrence compared with post-operative chemoradiation or preoperative radiotherapy alone. Long-term follow-up did not show any survival differences in patients who received neoadjuvant versus adjuvant chemo-radiation therapy.2–4 However, there is uncertainty as to whether adjuvant chemotherapy (CT) provides any additional benefit in patients who have previously received neoadjuvant CRT. Clinical trials that have attempted to address this inquiry have left clinicians with a lack of clarity. Several clinical trials suggested a lack of benefit for adjuvant CT following neoadjuvant chemoradiation and surgery in resectable rectal cancer. These studies had significant limitations that complicate interpretation including the inconsistent use of neoadjuvant chemoradiation (PROCTOR/SCRIPT), poor adherence (EORTC 22921), lack of optimal dosing, and/or prolonged postoperative complications.3,5–9

However, based on adjuvant CT recommendations extrapolated from stage III colon cancer data, current NCCN guidelines suggest patients with rectal tumors staged as a T3 or N1 and higher are to consider adjuvant fluoropyrimidine-based CT (either 5-FU or capecitabine) with or without oxaliplatin following neoadjuvant CRT and surgery.10–14 To assess the efficacy and outcomes of adjuvant CT following neoadjuvant therapy and surgery in rectal cancer, we conducted a study utilizing a prospectively maintained database in predefined patients with stage II or III rectal cancer who received neo-adjuvant chemoradiation followed by surgical resection and subsequent adjuvant CT at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Ohio State University Institutional Review Board. Data were obtained from a prospectively collected database for patients with stage II and III rectal cancer who were treated at the Ohio State University from August 2005 to July 2011. Patients were included in our analysis if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) histologically confirmed rectal cancer, (2) stage II or III disease, and (3) received neoadjuvant CRT and surgery. The time period from 2005 to 2011 was selected for the following reasons: (1) sufficient patient data were available for patients diagnosed in 2005; and (2) the 2011 cutoff allowed for sufficient follow-up at the time of outcome analysis. Using these data, we analyzed OS, time to recurrence (TTR), patient characteristics, tumor features, and treatments. OS was determined from the date of initial diagnosis to death of any cause. Patients who were still alive were censored at the date of last follow-up. TTR was calculated from the date of initial diagnosis to disease recurrence. Patients who were still disease free were censored at the date of last disease-free follow-up. Survival curves were estimated using Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Age was compared using the Wilcoxon test and other categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test. Duration of adjuvant CT was compared among the different types of adjuvant CT (1 drug vs. 2 drugs vs. unknown) using Kruskal-Wallis test. Multivariate Cox regression hazard models were used to adjust for patient characteristics and estimate hazard ratios with 95% CI for OS and TTR. A P-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

We identified 110 patients with stage II or III rectal cancer who were treated with neoadjuvant CRT between August 1, 2005 and July 31, 2011. Baseline patient and tumor characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of the 110 patients who were eligible to receive adjuvant CT, 39 patients (35%) did not receive adjuvant CT (Table 2). Of those, 29 (75%) did not receive adjuvant therapy due to physician discretion for reasons other than performance status, surgical complications, or comorbidities, 4 (10%) due to postoperative complications, 4 (10%) due to patient choice, and 2 patients (5%) developed metastatic disease shortly after resection (Table 2).

Table 1. Patient and Tumor Characteristics.

| N (%) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| No Adjuvant Chemotherapy (N = 39)* | Adjuvant Chemotherapy (N = 71) | ||

| Median age (range) (y) | 62 (21-79) | 54.3 (27-76) | 0.01 |

| Sex | 0.24 | ||

| Female | 12 (31) | 30 (42) | |

| Male | 27 (69) | 41 (58) | |

| Race | 0.07 | ||

| Black | 4 (10) | 1 (1) | |

| Chinese | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | |

| Other Asian | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| White | 35 (90) | 67 (94) | |

| Pathologic T stage | 0.75 | ||

| Pathologic T0-T1 | 10 (26) | 16 (24) | |

| Pathologic ≥T2 | 28 (74) | 52 (76) | |

| Pathologic N stage | 0.02 | ||

| Pathologic N0 | 29 (81) | 37 (57) | |

| Pathologic N1 | 5 (14) | 20 (31) | |

| Pathologic N2 | 2 (5) | 8 (12) | |

| Downstaging (decrease in either T or N in pathologic staging from clinical staging) | 0.10 | ||

| Yes | 25 (68) | 33 (51) | |

| No | 12 (32) | 32 (49) | |

| Complete pathologic response | 0.12 | ||

| Yes | 8 (21) | 7 (10) | |

| No | 31 (79) | 64 (90) | |

Table 2. Reasons Why Patients (N = 110) Did Not Receive Adjuvant Chemotherapy.

| Reasons | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Physician choice | 29 (26) |

| Patient choice | 4 (4) |

| Postoperative complications | 4 (4) |

| Developed metastatic disease shortly after resection | 2 (2) |

There were no significant differences in sex, race, pathologic tumor stage, downstaging after neoadjuvant chemoradiation, or complete pathologic response between patients who received adjuvant CT versus those who did not. However, patients who received adjuvant CT were younger with a median age of 54.3 years, in comparison with a median age of 62 years (P = 0.01) in patients who did not receive adjuvant treatment. Conversely, patients who were treated with adjuvant CT were less likely to achieve a pathologic complete response (10% vs. 21%, P = 0.12). These patients had more advanced pathologic nodal stage compared with patients who did not receive adjuvant therapy (43% vs. 19%, P = 0.02). All patients received a total mesorectal excision, the standard of care at our institution, with similar surgical procedures between patients who did or did not receive adjuvant CT, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Type of Surgery.

| N (%) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| No Adjuvant Chemotherapy (N = 39) | Adjuvant Chemotherapy (N = 71) | ||

| Abdominoperineal resection | 12 (31) | 23 (32) | 0.37 |

| Low anterior resection | 20 (51) | 41 (58) | |

| Total proctocolectomy | 1 (3) | 2 (2) | |

| Total pelvic extenteration | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| Transanal excision | 4 (10) | 6 (8) | |

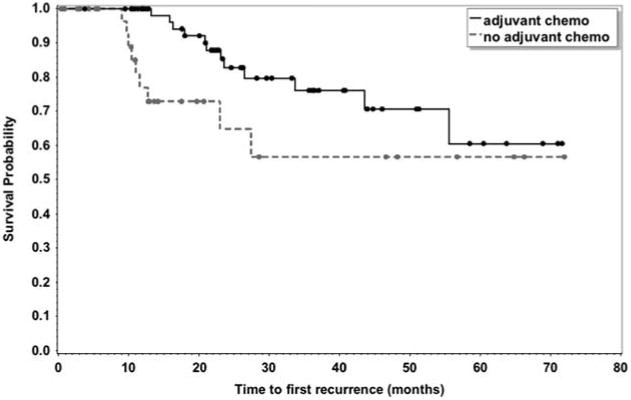

Overall, in patients who received adjuvant CT, the median duration of treatment was 3.5 months (range, 2 to 6 mo). Adjuvant CT regimen was based on physician choice, with 38 patients who received single-agent fluoropyrimidine (5-FU or capecitabine) and 33 patients received FOLFOX. In patients who received adjuvant CT, the median OS was 72.6 months compared with 36.4 months in patients who underwent observation (Fig. 1, OS; P = 0.0003). At the time of analysis, the median TTR was not reached. However, adjuvant CT had a trend toward an improvement in the median TTR (Fig. 2, TTR). Using a multivariate Cox regression model, and after adjusting for treatment, pathologic N status, and age, advantages in median OS and time to first recurrence in the adjuvant CT arm remained significantly improved in the adjuvant CT group (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Association between overall survival and adjuvant chemotherapy.

Figure 2.

Association between time to recurrence and adjuvant chemotherapy.

Table 4. Association Between Baseline Characteristics and OS/TTR.

| OS | TTR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | |

| Treatment | ||||

| No adjuvant Chemotherapy (reference) | — | — | — | — |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.18 (0.06-0.57) | 0.004 | 0.24 (0.08-0.71) | 0.01 |

| Pathologic N status | ||||

| N0 (reference) | — | — | — | — |

| N1-N2 | 1.35 (0.42-4.32) | 0.61 | 3.46 (1.33-8.99) | 0.01 |

| Age at diagnosis | 0.99 (0.94-1.03) | 0.50 | 0.96 (0.92-1) | 0.04 |

CI indicates confidence interval; OS, overall survival; TTR, time to recurrence.

Discussion

Despite the lack of evidence from randomized clinical trials supporting the use of adjuvant CT in rectal cancer following neoadjuvant CRT and surgical resection, it has become the de facto integrated strategy based on practice guidelines. The rationale for adjuvant therapy has been mostly based on data extrapolated from colon cancer trials in addition to the described patterns of recurrence seen in resected rectal cancer. A number of studies, including a recent Cochrane review, showed a 17% risk reduction in death and a 25% risk reduction in disease recurrence among rectal cancer patients who received neoadjuvant CRT and surgical resection followed by adjuvant CT compared with those who did not receive adjuvant CT.15–17 Other studies that investigated the use of adjuvant CT following neoadjuvant CRT and surgical resection (PROCTOR/SCRIPT, EORTC 22921) yielded negative results. In contrast, in our study, patients with resected rectal cancer following neoadjuvant CRT who received adjuvant CT were found to have a significant survival benefit and time to first recurrence over those who did not receive adjuvant therapy. Most recently, a number of studies presented at ASCO 2014 (ADORE, CAO/ARO/AIO-04) support the results of our findings by suggesting an improved clinical outcome in rectal cancer patients with advanced disease (stage II/III) who received neoadjuvant chemoradiation and surgery followed by adjuvant FOLFOX CT.9,18

In our study, patients who received CT were younger but had more advanced nodal disease involvement, an adverse prognostic factor. Among patients who did not receive adjuvant CT, 29 did not based on physician choice. Most commonly stated reasons for this choice were the absence of data that supported adjuvant treatment in this setting, less adverse prognostic factors such as less advanced disease, and less occasionally older age. Interestingly, the OS benefit advantage persisted in a multivariable model after controlling for the baseline characteristics of age and nodal status.

Principle limitations to interpreting the results of our study include its retrospective nature, although the data were analyzed from a prospectively collected database, its limited sample size, and the fact that this is a single-center setting that may cause a selection bias. Among the parameters we examined, we did not take into account tumor location, which could have created an imbalance and effected outcomes between the patients who did and did not receive CT. Moreover, of the 39 patients who did not receive adjuvant CT, we reported documented reasons as to why they did not receive adjuvant treatment; however, there might have been an unforeseen and unaccounted bias in the selection of patients who received adjuvant CT.

In conclusion, based on our findings and those from most recent studies, for patients with stage II/III rectal cancers who are treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiation and surgical resection, strong consideration should be given to adjuvant CT. Although there seems to be a significant benefit in OS, further refinement is needed to determine the (clinical or molecular) subset of patients that is most likely to benefit from CT. It is also essential to determine the optimal duration and intensity of the adjuvant CT regimen. Finally, integrating novel-targeted therapies such as immunotherapies (eg, PDL-1) should be of prime interest.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, et al. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sauer R, Becker H, Hohenberger W, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1731–1740. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosset JF, Collette L, Calais G, et al. Chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1114–1123. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerard JP, Conroy T, Bonnetain F, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy with or without concurrent fluorouracil and leucovorin in T3-4 rectal cancers: results of FFCD 9203. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4620–4625. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glimelius B, Tiret E, Cervantes A, et al. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl 6):vi81–vi88. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breugom AJ, van den Broek CBM, van Gijn W, et al. The value of adjuvant chemotherapy in rectal cancer patients after preoperative radiotherapy or chemotherapy followed by TME-surgery: the PROCTOR/SCRIPT study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:S1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cionini L, Sainato A, De Paoli A, et al. Final results of randomised trial on adjuvant chemotherapy after preoperative chemoradiation in rectal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2010;96:S113–S114. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosset JF, Calais G, Mineur L, et al. Enhanced tumorocidal effect of chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer: preliminary results—EORTC 22921. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5620–5627. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosset JF, Calais G, Mineur L, et al. Fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy after preoperative chemoradiotherapy in rectal cancer: long-term results of the EORTC 22921 randomised study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:184–190. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andre T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2343–2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuebler JP, Wieand HS, O'Connell MJ, et al. Oxaliplatin combined with weekly bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin as surgical adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II and III colon cancer: results from NSABP C-07. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2198–2204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. [Accessed November 1, 2014];National Comprehensive Cancer NetworkRectal cancer. Available at: http://www.nccn.org.

- 13.Benson AB, Catalan P, Meropol NJ, et al. ECOG E3201: intergroup randomized phase III study of postoperative irinotecan, 5-fluorouracil (FU), leucovorin (LV) (FOLFIRI) vs. oxaliplatin, FU/LV (FOLFOX) vs. FU/LV for patients with stage II/III rectal cancer receiving either pre or postoperative radiation (RT)/FU. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18S):3526. 2006. ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofheinz RD, Wenz F, Post S, et al. Chemoradiotherapy with capecitabine versus fluorouracil for locally advanced rectal cancer: a randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:579–588. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70116-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Connell MJ, Martenson JA, Wieand HS, et al. Improving adjuvant therapy for rectal cancer by combining protracted-infusion fluorouracil with radiation therapy after curative surgery. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:502–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408253310803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen SH, Harling H, Kirkeby LT, et al. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy in rectal cancer operated for cure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD004078. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004078.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krook JE, Moertel CG, Gunderson LL, et al. Effective surgical adjuvant therapy for high-risk rectal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:709–715. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103143241101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong YS, Nam B, Kim KP, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with oxaliplatin/5-fluorouracil/leucovorin (FOLFOX) versus 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin (FL) for rectal cancer patients whose postoperative yp stage 2 or 3 after preoperative chemoradiotherapy: updated results of 3-year disease-free survival from a randomized phase II study (The ADORE) J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl):5s. abstract 3502. [Google Scholar]