Abstract

Objectives

Adolescents with juvenile fibromyalgia (JFM) are typically sedentary despite recommendations for physical exercise, a key component of pain management. Interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are beneficial but do not improve exercise participation. The objective of this study was to obtain preliminary information about the feasibility, safety, and acceptability of a new intervention - Fibromyalgia Integrative Training for Teens (FIT Teens), which combines CBT with specialized neuromuscular exercise training modified from evidence-based injury prevention protocols.

Methods

Participants were 17 adolescent females (ages 12–18) with JFM. Of these, 11 completed the 8-week (16-session) FIT Teens program in a small-group format with 3–4 patients per group. Patients provided detailed qualitative feedback via individual semi-structured interviews after treatment. Interview content was coded using thematic analysis. Interventionist feedback about treatment implementation was also obtained.

Results

The intervention was found to be feasible, well-tolerated, and safe for JFM patients. Barriers to enrollment (50% of those approached) included difficulties with transportation or time conflicts. Treatment completers enjoyed the group format and reported increased self-efficacy, strength, and motivation to exercise. Participants also reported decreased pain and increased energy levels. Feedback from participants and interventionists was incorporated into a final treatment manual to be used in a future trial.

Discussion

Results of this study provided initial support for the new FIT Teens program. An integrative strategy of combining pain coping skills via CBT enhanced with tailored exercise specifically designed to improve confidence in movement and improving activity participation holds promise in the management of JFM.

Keywords: juvenile fibromyalgia, pediatric chronic pain, cognitive-behavioral therapy, physical exercise

Introduction

Juvenile Fibromyalgia (JFM) is a chronic musculoskeletal pain condition that occurs in 2–6% of children, primarily adolescent girls [1–5], and is associated with significant physical and emotional impairment [6–11]. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been found to be effective in reducing functional disability and depressive symptoms in JFM [12]; however, CBT alone has relatively modest effects on pain reduction [12]. One possible reason is because CBT treatment by itself does not result in greater engagement in more vigorous types of activity or exercise [13]. In particular, for musculoskeletal conditions such as JFM, engagement in regular physical exercise is recommended for pain management [14], and this not well addressed in traditionally delivered CBT. Several studies have shown the benefits of both aerobic and strengthening exercise programs in reducing pain [15–19]. Yet, in order for exercise to be effective in the long term, patients need to incorporate exercise into their daily routine even after formal training programs have ended [15]. Adequate maintenance of daily physical activity is a primary challenge for patients with fibromyalgia because the majority, including adolescents with JFM [20–22], are sedentary and adherence to exercise regimens in fibromyalgia patients is generally found to be quite poor [23, 24].

Barriers to maintenance of exercise in patients with fibromyalgia may be related to pain, activity avoidance and features of the disease itself that make patients more prone to experiencing increased pain with exercise. It has been found that adolescents with chronic pain tend to reduce physical activity following days with higher pain intensity [25] and that adolescents with JFM show decreased strength and altered biomechanics [26]. Studies in adults have indicated that patients with fibromyalgia have dysfunctional pain inhibition whereby they do not show the typical endogenous hypoalgesia following exercise [27–29]. Thus the combination of JFM pain, pain-related activity-avoidance and poor body mechanics likely makes exercise difficult and uncomfortable [30–32] and may ultimately resulting in a downward spiral of pain and disability [33, 34].

A recent study documented altered biomechanics, decreased strength and deficits in functional performance, along with marked self-reported fear of movement in adolescents with JFM compared to their healthy peers [35]. The movement patterns identified in these patients using sophisticated biomechanical tests including 3-dimensional motion analysis are similar to movement deficits that place individuals at risk for injury [36, 37]. Therefore, traditional aerobic or resistance training programs may be difficult to sustain for patients with JFM because of poor movement confidence and a lack of fundamental movement competence. It has become clear that tailored exercise programs are needed for fibromyalgia patients [28] but thus far, finding the most appropriate type of exercise that is both tolerable and sustainable for these patients has been a challenge for the field. Using what is known from injury prevention research from the field of exercise science in conjunction with the knowledge we have gained about improving psychological coping skills from our evidence-based CBT program, we have devised a new and innovative treatment - the Fibromyalgia Integrative Training for Teens (FIT Teens) program. This intensive 8-week program is focused on enhancing CBT with the integration of specialized neuromuscular exercise training [38, 39]. FIT Teens was designed to instill confidence in patients with JFM to safely engage in physical activity and motivate them to incorporate regular exercise which could be an important step towards improved fibromyalgia pain control.

Integrative neuromuscular exercise training focuses on the development of core strength, conditioning, and fundamental movement skills [38, 40]. This approach has been well studied in adolescent athletes and found to improve core stability and strength [38, 41–44]. However, to our knowledge neuromuscular training has not yet been employed with adolescents with JFM, nor has it been applied in combination with CBT. The neuromuscular training component of the FIT Teens program was tailored for adolescents with JFM through a careful iterative process including consultation with experts in rheumatology, sports medicine/exercise science, and behavioral medicine. Exercise progressions were specifically modified to gradually increase the level of challenge and minimize muscle actions that would induce delayed-onset muscle soreness that might mimic JFM symptoms. The CBT components of the program were based on our established CBT treatment [12] modified to include application to in-vivo exercise training (e.g., activity pacing, breathing relaxation techniques, distraction, dealing with negative thoughts/anticipation of pain) which were closely integrated with the exercise component.

The primary objectives of this pilot, qualitative study were to 1) obtain information about the feasibility, safety, and tolerability of the 8-week (16 session) group-based FIT Teens intervention for adolescents with JFM and 2) gather detailed feedback from participants about their impressions of the acceptability, format, and content of the program. We hypothesized that the program would be feasible in terms of patients’ willingness to participate, and safe/tolerable – because the CBT component is already well-tested and the newly added exercise component is progressive and specially designed to minimize pain. We further anticipated that the JFM patients would enjoy the group-format of training with other similar-age JFM patients, and find the content beneficial.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Patients were eligible if they were 12–18 years old and diagnosed with JFM by a pediatric rheumatologist or pain physician. Consistent with our prior studies, we used the Yunus and Masi (1985) criteria for JFM classification which require widespread pain, associated symptoms (fatigue, sleep disturbance etc.), and at least 5 painful tender points upon palpation [5]. Additional inclusion criteria were: moderate to high level of disability (Functional Disability Inventory score ≥ 12 [45]); and moderate pain intensity (≥ 4 on a 0–10 cm visual analog scale of average pain). Exclusion criteria were: diagnosis of a comorbid rheumatic disease (e.g., juvenile arthritis, systemic lupus erythematous), untreated major psychiatric diagnosis (e.g., major depression, bipolar disorder, and psychosis), use of opioid medication, documented developmental delay, or any other medical condition determined by their physician to be a contraindication for exercise (e.g., severe orthostatic hypotension, vertigo, recent surgery or untreated seizure disorder), or ongoing participation in CBT for pain.

Recruitment

Potential participants meeting screening criteria were identified by a trained research assistant from pediatric rheumatology and pain clinics at a large children’s hospital. Medical eligibility was confirmed by a physician who introduced the study to patients and their caregivers. If interested, a research assistant provided a thorough overview of the study, answered any questions, and obtained written informed consent and assent. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the children’s hospital.

Intervention

The format of the initial FIT Teens program piloted in this study was 16 in-person sessions (twice per week) in a small-group format, 60 minutes for each session (~30 minutes each devoted to CBT and neuromuscular training). The intervention took place at a Children’s Hospital in the Sports Medicine Biodynamics and Human Performance Laboratory (similar to a gym setting) with the CBT component conducted in an adjoining conference room. Sessions were led jointly by a psychology post-doctoral fellow with specialized training in pediatric pain and a master’s level exercise physiologist who was experienced (5+ years) in the delivery of neuromuscular training as part of injury prevention research protocols. They were supervised by a senior licensed psychologist (SKZ) and a doctoral level Sports Medicine researcher (GDM) via weekly team meetings.

The CBT components of the program were based on our published clinical trial [12] and consisted of training pain coping skills including education about the gate-control theory of pain, relaxation skills, distraction, activity pacing, problem solving, and modifying negative and catastrophic thoughts about pain. The content was modified to apply coping skills in-vivo while participants learned neuromuscular exercises for a more integrated approach. The specialized resistive training protocol used in neuromuscular training progressed through four levels focusing on a different muscle action; Level 1: Holding Exercises, Level 2: Creating Movement Exercises, Level 3: Resisting Movement Exercises, and Level 4: Functional Movement Exercises (see Table 1. for a description of each level of progression along with an illustrative example; complete protocol published in Thomas et al. [46]). The progression of exercises was collectively designed in order to reduce muscle pain and delayed-onset muscle soreness by moving from most basic isometric “hold” exercises to concentric “muscle shortening” exercises to eccentric “muscle lengthening” exercises to the full range of motion for “functional movement”. By gradually building upon the foundation of movement by focusing on each type of muscle action, the protocol allows participants to master each level before advancing. The final level is designed to pull together each level into functional movements that are relevant for activities of daily life. New exercises were introduced every 2 weeks with ongoing constructive feedback regarding proper form and technique before being incorporated into the full functional movement exercises in Level 4. The program was also tailored to minimize pain during exercise by specifically tailoring the program to each person based on their baseline levels of fitness and confidence. For example, for patients unable to perform a squat, minimizing the range of motion and providing external support were the some of the modifications made which participants practiced until they were able to achieve a squat position. In contrast to traditional resistance training programs, this protocol did not include any external resistance exercises. Rather, exercises were designed to mimic movements that occur in normal daily activities and individualized for difficulty based upon participants’ baseline ability. Further, the exercise trainer ensured neutral joint positioning, particularly for any JFM patients with co-occurring joint hypermobility (as documented by a Beighton score ≥ 5) for whom joint protection should be kept in mind. Education was provided to all patients normalizing temporary muscle soreness when beginning a new exercise regimen and differentiating muscle soreness from a JFM pain flare.

Table 1.

Example of exercise progression along with instructions to perform the exercise

| Level | Type of Movement | Example Exercise | Description of Exercise |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Hold Exercises” (Isometric) |

BOSU Double Leg Deep Hold w/ TRX Upper Body Assistance

|

The patient starts by standing on the BOSU with the round side up and holding onto the TRX handles. Then, the patient bends their hips and knees until their knees are bent to approximately 90°, using the TRX handles as support. The patient holds this position for the prescribed time. |

| 2 | “Creating Movement Exercises” (Concentric) |

BOSU Double Leg Squat UP - with TRX Assistance DOWN |

The patient starts by standing on the BOSU with the round side up and holding onto the TRX handles. Then, the patient bends their hips and knees until their knees are bent to approximately 90°, using the TRX handles as support on the way down. The patients will slowly (3 count) raise themselves back to the starting position, using as LITTLE support from the TRX handles as possible (arms are relaxed). |

| 3 | “Resisting Movement Exercises” (Eccentric) |

BOSU Double Leg Squat DOWN - with TRX Assistance UP |

The patient starts by standing on the BOSU with the round side up and holding onto the TRX handles. Then, the patient slowly (count of 3) bends their hips and knees until their knees are bent to approximately 90°, using the TRX handles as LITTLE as possible for support on the way down. With support from the TRX handles, the patient will raise back to the starting position. |

| 4 | Functional Movement Exercises |

BOSU Squats w/ TRX Upper Body Assistance |

The patient starts by standing on the BOSU with the round side up. Then, the patient bends their hips and knees until their knees are bent to approximately 90°. The patient then returns to the starting position and repeats. Using the TRX for a LITTLE assistance as possible through the entire range of motion. |

At the end of each session, participants were provided home practice instructions for coping skills and physical exercises along with daily diaries to monitor progress. Participants were requested to complete a daily paper-pencil diary once at the end of each day with ratings of daily pain intensity and fatigue (both rated on a 0–10 scale), and practice of coping skills and physical exercise. Diaries were reviewed by the trainers at the following session to discuss progress and problem-solve barriers to independent home practice. Missed sessions were re-scheduled to ensure that all participants received the full course of the intervention.

Post-Intervention Interview

After the final session, adolescents met individually with a trained research staff member who was not part of the treatment team to complete a 30–45 minute semi-structured interview. The majority of interviews were conducted in-person, and one interview was conducted over the phone due to scheduling difficulties. All interviews were digitally audio-recorded, assigned an identification number to anonymize content, and transcribed for coding. Interview questions (Appendix 1) were developed a priori to examine the feasibility, tolerability, safety, content, and format of the new FIT Teens program. The interview included uniform open-ended questions, which offered flexibility for participants to provide additional relevant information and for the interviewer to ask clarifying questions.

Feedback from Interventionists

In addition to qualitative information from participants, the exercise physiologist and psychotherapist provided feedback regarding implementation of the study protocol throughout the FIT Teens program during weekly supervision meetings. They also maintained session logs documenting safety and tolerability (reports of pain during specific exercises, soreness after exercises, any JFM pain flares). Interventionists’ feedback was reviewed throughout the program to clarify the need for subsequent protocol refinements.

Data Analysis

Regarding the domain of feasibility, the number of patients approached, the number who agreed to participate and those that declined (and reasons for declining) was recorded. The number of patients who dropped out and reasons for drop out were also documented. To assess for safety, the trainers recorded adverse events (e.g., any falls, injuries, excessive pain or any symptom requiring medical consultation caused by the training exercises) at each session. Temporary muscle soreness in the muscles being “worked” during exercise was an expected reaction as most patients with JFM have some level of deconditioning - and therefore not defined as an adverse reaction. Trainers tracked participants’ ability and comfort completing exercises during each session as one indicator of tolerability. Trainers kept a log of participants’ completion, modification, and level of difficulty of exercises completed by each patient and any adverse events at each session.

Qualitative Interview Analysis

Informed by Grounded Theory [47], thematic analysis [48], a rigorous, systematic and iterative method, was used to classify the verbatim responses from patients. Each transcript was reviewed independently by two trained coders (from a team including a clinical psychologist, a psychology resident, and two clinical research coordinators) and a line-by-line content analysis was used to extract data that detailed the feasibility, safety, tolerability, format, and content of the FIT Teens program. Themes were identified, defined, and refined through review of the interviews. Regular coding meetings were held to discuss the identified themes. When discrepancies occurred or content appeared to overlap more than one domain, the coders clarified the meaning of emerging themes by reviewing transcripts for contextual supporting information to inform a consensus interpretation of the text, and data were assigned to the one domain which best represented the content. Finally, domains were identified based on commonalities among themes reported by participants.

Study Interventionist feedback

The trainer and therapist made notes/comments about the implementation of the protocol at each session which were used by the team to make iterative changes after each group ended.

Results

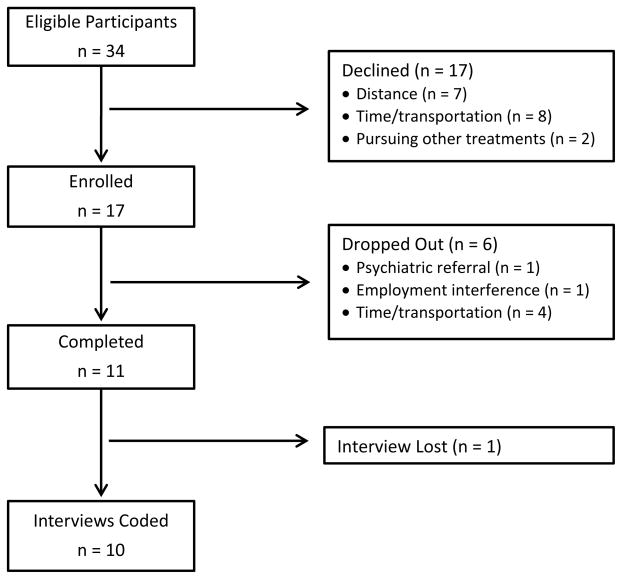

Of the 34 eligible patients approached to participate, 17 declined (7 due to distance from the hospital, 8 for time/transportation constraints, and 2 for pursuing other treatments), and 17 enrolled over the course of one year. Six participants dropped out: one individual reported suicidal ideation that was not revealed at the initial evaluation and was referred for psychiatric care, one started employment that interfered with program completion, and four others had difficulty making regular appointments and transportation arrangements. A total of 11 participants (all female, 12–18 years, M = 16.00 years, SD = 2.15) completed the FIT Teens program in its entirety during three 8-week groups and completed the post-intervention interview. One interview was lost due to recorder malfunction; therefore, 10 complete interviews were available for coding and analysis.

Mean disability score on the Functional Disability Inventory for the group was in the moderate range (M = 24.09, SD = 11.42) and the mean pain rating for the past week (0–10 scale) was 5.87 (SD = 1.96). Patients obtained their usual medication management through our pain and rheumatology clinics. Typical medications used in these clinics include one or more of the following: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or anticonvulsants (i.e., gabapentin) for pain, tricyclic antidepressants (i.e., amitriptyline) or muscle relaxants (i.e., cyclobenzaprine) for sleep, and serotonin and/or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, if needed, for mood symptoms.

Regarding safety, no adverse events were recorded during the intervention. A few participants reported occasional JFM pain flares during the intervention time span, but they reported that they were able to distinguish between pain/soreness after exercise and their usual JFM pain fluctuations that they believed were not due to the introduction of new exercises. In terms of tolerability, while modifications were made on an individual basis according to ability (e.g., starting with a half squat without using the full range of motion if needed), all participants were able to perform a form of each exercise. Patient reports of pain or inability to perform a new exercise was used by the exercise trainer as a cue to modify the exercise to a lower level of challenge until the patient was able to do the exercise with minimal discomfort.

The content of the interviews was categorized into the following a priori domains: 1) Feasibility, 2) Tolerability/Acceptability, 3) Safety, 4) Content, and 5) Format. Within each domain, common themes were identified and defined (see bold italics), and key quotes that encapsulated each theme were identified. Two additional domains that emerged beyond the a priori categories were: 1) Perceived Efficacy and 2) Continued Physical Activity Participation. Primary findings are summarized below by content domain, with representative quotes from each theme provided in Tables 2–7.

Table 2.

Representative Quotes from Domain 1: Feasibility

Theme: Practice

|

Theme: Usability of Skills

|

Theme: Program Adherence

|

Theme: Barriers to Feasibility

|

Table 7.

Additional Domains

| Representative Quotes from Domain 6: Perceived Efficacy |

Theme: Confidence and Self-Efficacy

|

Theme: Strength and Stamina

|

Theme: Physical Functioning

|

Theme: Reduction in Physical Symptoms

|

Theme: Sleep

|

| Representative Quotes from Domain 7: Continued Physical Activity Participation |

|

Domain 1: Feasibility

Overall, participants reported that the coping skills and the physical exercises were easy to learn and perform within the sessions (Table 2). Most participants also provided specific examples of how they were able to regularly practice the skills they learned. Additionally, all participants described the usability of skills outside of sessions. Several participants discussed aspects of the program that enhanced its utility and their ability to adhere to the regimen. In particular, the specialized exercise program and being able to learn new exercises along with other teens with JFM was stated as a positive and motivating aspect of the program. Regarding barriers to feasibility, participants also identified potential barriers to maintaining the treatment regimen, including difficulty exercising during pain flares, fatigue, or demands on their time after school.

Domain 2: Tolerability/Acceptability

Participants expressed no difficulties with the coping skills component of treatment. With respect to the integrated neuromuscular training, most participants observed that although the exercises were challenging and they could feel their muscles “working”, exercises were physically tolerable (Table 3). Nearly all participants reported that the pace and progression of learning exercises was a positive feature, and the majority reported that the interventionists appropriately modified the exercises as needed to meet individual levels of ability. Teens consistently identified some exercises as being the most difficult, particularly those including squats, hamstring curls, lying prone while extending arms and legs (“Superman”), and hip hinge on one leg. However, participants reported that if needed, the exercise physiologist made modifications to these exercises and they were able to perform them correctly. Several participants reported liking the squats and hamstring curls by the end of the program.

Table 3.

Representative Quotes from Domain 2: Tolerability/Acceptability

Theme: Exercise Tolerability

|

Theme: Pace and Progression

|

Theme: Difficult Exercises

|

Theme: Modifications

|

Domain 3: Safety

Participants generally reported that it was helpful to learn new exercises with modifications as needed in a supportive environment (Table 4). About half of the participants reported that it was useful to learn how to exercise with good form. Some participants also described that the intervention provided appropriate supervision and reassurance to ensure that participants felt comfortable with the level at which their physical abilities were challenged (supportive environment). Half of participants reported no pain flares, or a reduction in pain flares during the program; the other half reported experiencing typical JFM pain fluctuations that were described as unrelated to the exercises. Some participants reported soreness/aches or fatigue after the exercise sessions; one participant stated that this was likely due to an increase in overall physical activity from her baseline level of (in)activity.

Table 4.

Representative Quotes from Domain 3: Safety

Theme: Good Form

|

Theme: Supportive Environment

|

Theme: Reduction in Pain Flares

|

Theme: Soreness/Aches/Fatigue

|

Theme: Fibromyalgia Pain versus Exercise-Induced Muscle Soreness

|

The majority of participants also described learning to differentiate between their typical fibromyalgia pain versus exercise-induced muscle soreness which was more temporary.

Domain 4: Content

Overall, participants gave favorable reviews of exercises and coping skills learned during the intervention (Table 5). All participants gave examples of exercises that they particularly liked, highlighting 12 specific exercises out of the total 32. All participants also gave examples of coping skills that they liked, specifically mentioning all 7 coping skills.

Table 5.

Representative Quotes from Domain 4: Content

Theme: Exercises

|

Theme: Coping Skills

|

Theme: Least Favorite Exercises

|

Theme: Least Favorite Coping Skills

|

Theme: Combined Treatment

|

Participants identified specific exercises and coping skills that they did not like and described the reasons for their dislike (least favorite exercises and coping skills). Generally, participants described disliking specific neuromuscular exercises due to difficulty performing the exercise or feeling that the targeted muscles were not “working”. Less preferred coping skills were those that required more time to complete or those that they practiced less frequently (e.g., progressive muscle relaxation).

Most participants also demonstrated understanding of how the coping skills and physical exercise portions of the intervention were complementary (combined treatment).

Domain 5: Format

Participants were unanimously positive about the group format, mainly due to the supportive and encouraging group environment and the opportunity to meet other patients with JFM (Table 6). The majority of participants also enjoyed the structure of the program, progressively learning new exercises every two weeks before ultimately creating the full functional movement, and monitoring their own progress. With respect to challenges of the group format, two participants felt that it was sometimes difficult to get one-on-one attention when the trainer turned away to focus on other group members, and one participant would have preferred not to discuss coping skills in a group setting.

Table 6.

Representative Quotes from Domain 5: Format

Theme: Group Format

|

Theme: Structure of the Program

|

Theme: Challenges of Group Format

|

Additional Domains

Domain 6: Perceived Efficacy

Overall, participants reported feeling more confident and noticing a number of positive changes at the end of the FIT Teens program (Table 7). Nearly all participants reported increased confidence and self-efficacy as a result of the program, having a sense of pride in their accomplishment, and being happier. The majority also reported noticing a progressive increase in their strength, stamina, and physical functioning. Most participants also reported noticing a reduction in physical symptoms as a result of the program, particularly a reduction in pain. Over half of the participants also reported improvement in sleep, or feeling rested or having more energy during the day. Specifically, five reported reducing or eliminating naps from their routine. Two participants reported continued difficulty with sleep (e.g., falling asleep).

Domain 7: Continued Physical Activity Participation

During the program, all participants noted that they had increased their overall daily physical activity, incorporated planned physical activities into their daily schedules (Table 7), and experienced increased motivation to go out or be with their friends even if they had pain.

Feedback from Trainers

The psychotherapist and exercise physiologist provided feedback throughout the FIT Teens program in order to consider the need for subsequent protocol refinements. The timing of the sessions (3:00–4:00 pm) was reported to be a barrier for some patients, as they were unwilling to miss school to attend the program. Additionally, the interventionists noted that the length of sessions (60 minutes) was too short– there was not enough time to review homework in addition to learning and practicing new material (CBT and exercises). The exercise physiologist made note of modifications made to specific exercises for patients who reported pain/discomfort performing the exercise, and modifications for those patients who had co-occurring joint hypermobility (commonly seen in JFM patients). No safety issues were reported or adverse effects other than the expected temporary muscle soreness after initiating new exercises. The interventionists also felt that the participants needed more instruction on how each exercise was connected to daily activities such as walking up and down stairs, sitting in class or standing for a long period of time. The psychotherapist noted that many participants brought up sleep as a problem area, and there were no specific instructions on sleep hygiene in the CBT protocol. Finally, several participants had difficulty with the translatability of skills to real life, in particular remembering to do homework and increasing physical activity. This feedback was taken into consideration and changes were made (the details of which are offered in the Discussion) iteratively after each group in order to refine the intervention.

Discussion

The results of the current pilot investigation provided initial support for the feasibility and acceptability of an integrative CBT and neuromuscular training program for adolescents with JFM. The primary goal of this investigation was to obtain direct feedback from participants regarding implementation barriers to the behavioral and exercise-based skills taught during the sessions, their comfort with the format and content of the training program, and whether they found it helpful in the management of their symptoms associated with JFM. Information gleaned from individual, semi-structured interviews, along with the feedback from study staff confirmed that this innovative combined intervention was overall very well-received, safe, and potentially efficacious for adolescents with JFM.

Particular strengths of the FIT Teens intervention noted by participants were: 1) the group format – which made participants feel supported and validated in their experiences, 2) the integration of both psychological and physical interventions within the same program, 3) the progressive increase in challenge of the neuromuscular exercises and the education in proper form to exercise safely, 4) the trainers’ ability to modify the exercises to participants’ baseline abilities, and 5) the increased confidence and sense of strength. The trainers also noted that the group format allowed much greater patient engagement and participation and increased participants’ ability to learn from and motivate one another. For example, during the course of treatment patients could assist one another (e.g., working in pairs). Also, a natural tendency to cheer and support the other members or make suggestions about how to improve technique emerged within the group members which would not occur in a one-on-one training environment. Early evidence for the efficacy of the program was suggested by participants’ comments about decreases in pain flares, increased energy, reducing/eliminating naps, and participating in more activities. Interestingly, despite the research showing that isometric exercise can lead to increased pain sensitivity (at least in the short term)[29], this did not appear to hinder patient’s progression through the exercise training. Perhaps the tailoring of the program which allowed for modifications of each exercise to improve tolerability with gradual increase in the level of challenge coupled with the emphasis on use of positive coping strategies and group support were jointly effective in ensuring that initial muscle soreness did not deter patients from engaging in the exercises.

In addition to the positive feedback obtained from participants about the program, this pilot study helped identify potential challenges to feasibility in implementing an intensive behavioral intervention requiring significant time commitment and effort from participants and families. About half of the eligible participants were unable to participate in the intervention and a few dropped out, citing distance from the hospital or difficulty in coming for appointments two times per week. Therefore, only the more motivated families and/or those with adequate time are likely to participate. In this study, participants were reimbursed a modest amount for gas expenses and there was no cost to the patients or their insurance companies for the sessions. Therefore, financial barriers were not a concern in this study but may arise in clinical care. These are realistic challenges in implementing any self-management training program that requires multiple in-person visits. To reduce attrition after starting the treatment, we made adjustments to the inclusion criteria to assess for complex psychiatric needs beyond the scope of the treatment (e.g. suicidal ideation) so that such patients can be referred to more appropriate care. Also, we moved the sessions to after school hours which were preferable to families. Although efforts are being made to make some self-management interventions (e.g., CBT) more accessible in web-based format [49, 50], the neuromuscular training requires close supervision of patients who have poor movement skills to ensure proper form and safety. Also, the integration of CBT with exercise requires in-vivo exposure for maximal effectiveness. We are therefore conducting initial rigorous testing of the FIT Teens intervention as a “proof-of-concept” to develop the manualized protocol which can then be delivered in community settings where physical therapists and trainers are more readily available and can be easily trained in the protocol.

In response to the feedback from patients and interventionists, several modifications to the protocol were iteratively made. Also, the psychological screening procedures were further refined, including specific assessment of recent or ongoing suicidal ideation which would require intervention outside the scope of this program. After the first group (and implemented in the second group), the duration of each session was increased from 60 to 90 minutes to allow sufficient time to cover the material and discuss home practice, a later start time after school (4:00pm or later) was offered, specific content on sleep hygiene was added, and the protocol was expanded to include written instructions at the end of sessions to address participants’ difficulty remembering homework. For the third group, the exercise physiologist began illustrating the utility of each exercise through pictures demonstrating how each exercise relates to daily physical tasks and including explicit guidelines for gradually increasing moderate-vigorous physical activity at home (i.e., brisk walking, playing a sport, swimming) to emphasize the importance of increased physical activity outside of session. Although participants reported increased participation in physical activity, specific activity goals were added (starting with 5 min of moderate activity of their choice, once a week) and progressively increased to 30 minutes of moderate-vigorous activity at least twice a week by the end of treatment to match the recommended exercise guidelines for patients with fibromyalgia [14].

In conclusion, this study obtained extensive patient-centered information related to the feasibility, acceptability, safety, and content of a new integrative treatment program for adolescents with JFM. The refined FIT Teens protocol incorporates feedback from the teens themselves as well as the trainers and research staff to arrive at a final protocol that is now ready to be tested in a randomized clinical trial. This combined program offers a promising new approach beyond currently available CBT-only programs [12] and exercise-only programs [16]. Although there is evidence from clinical treatment programs that multidisciplinary care is a useful treatment for pediatric chronic pain [51], the innovative FIT Teens program has the advantage of being carefully developed from an evidence-based CBT protocol integrated with a highly novel and specialized approach to the delivery of exercise training (neuromuscular training) that has never been tried in chronic pain populations.

Future goals are to compare the efficacy of FIT Teens to traditional exercise programs such as graded aerobic exercise and to our established CBT intervention in rigorously designed studies to determine whether FIT Teens leads to superior outcomes. Future studies on the specific mechanisms of pain responses to different types of exercise in JFM patients is needed and results could be used to inform more finely tailored programs. If found to be successful, the FIT Teens program will make available an evidence-based treatment manual for CBT and physical exercise (requiring minimal equipment) to be translated into regular clinical care for patients with JFM. The ultimate goal is to develop an integrated evidence-based treatment that can be disseminated widely for the treatment of adolescents and result in long-term pain control and a healthy lifestyle that reduces the likelihood of activity limitations and decreased quality of life due to JFM.

Figure 1.

Participant Flow Chart

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS)/NIH Grants K24AR056687 and R21AR063412 to the first author and support from the Division of Behavioral Medicine and Clinical Psychology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

We would like to thank Drs. Hermine Brunner, Kenneth Goldschneider, Michael Henrickson, Jennifer Huggins, Anne Lynch-Jordan, Esi Morgan-DeWitt, John Rose and Alex Szabova and for assistance with identification of eligible patients for the study. We would also like to thank the patients and families who participated in the study for their time and effort and for providing constructive feedback that was used to improve and refine the intervention program.

References

- 1.Gedalia A, Press J, Klein M, Buskila D. Joint hypermobility and fibromyalgia in schoolchildren. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52:494–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.7.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerloni V, Ghirardini M, Fantini F. Assessment of nonarticular tenderness and prevalence of primary fibromyalgia syndrome in healthy Italian schoolchildren. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1998;41:1405. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mikkelsson M, Salminen JJ, Kautiainen H. Non-specific musculoskeletal pain in preadolescents. Prevalence and 1-year persistence Pain. 1997;73:29–35. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00073-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sardini S, Ghirardini M, Betelemme L, Arpino C, Fatti F, Zanini F. Epidemiological study of a primary fibromyalgia in pediatric age. Minerva Pediatrica. 1996;48:543–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yunus MB, Masi AT. Juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome. A clinical study of thirty-three patients and matched normal controls. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1985;28:138–45. doi: 10.1002/art.1780280205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kashikar-Zuck S, Allen R, Noll R, Graham T, Ho I, Swain N, Crain B, Mullen S. Anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescents with juvenile fibromyalgia and their mothers. The Journal of Pain. 2005;6:31. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kashikar-Zuck S, Johnston M, Ting TV, Graham BT, Lynch-Jordan AM, Verkamp E, Passo M, Schikler KN, Hashkes PJ, Spalding S, Banez G, Richards MM, Powers SW, Arnold LM, Lovell D. Relationship between school absenteeism and depressive symptoms among adolescents with juvenile fibromyalgia. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35:996–1004. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kashikar-Zuck S, Lynch AM, Graham TB, Swain NF, Mullen SM, Noll RB. Social functioning and peer relationships of adolescents with juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2007;57:474–80. doi: 10.1002/art.22615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kashikar-Zuck S, Lynch AM, Slater S, Graham TB, Swain NF, Noll RB. Family factors, emotional functioning, and functional impairment in juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;59:1392–8. doi: 10.1002/art.24099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kashikar-Zuck S, Parkins IS, Graham TB, Lynch AM, Passo M, Johnston M, Schikler KN, Hashkes PJ, Banez G, Richards MM. Anxiety, mood, and behavioral disorders among pediatric patients with juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2008;24:620–6. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31816d7d23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kashikar-Zuck S, Vaught MH, Goldschneider KR, Graham TB, Miller JC. Depression, coping and functional disability in juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome. Journal of Pain. 2002;3:412–419. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2002.126786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kashikar-Zuck S, Ting TV, Arnold LM, Bean J, Powers SW, Graham TB, Passo MH, Schikler KN, Hashkes PJ, Spalding S, Lynch-Jordan AM, Banez G, Richards MM, Lovell DJ. Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of juvenile fibromyalgia: A multisite, single-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:297–305. doi: 10.1002/art.30644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kashikar-Zuck S, Flowers SR, Strotman D, Sil S, Ting TV, Schikler KN. Physical activity monitoring in adolescents with juvenile fibromyalgia: findings from a clinical trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:398–405. doi: 10.1002/acr.21849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Pain Society. Guideline for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome pain in adults and children. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauser W, Klose P, Langhorst J, Moradi B, Steinbach M, Schiltenwolf M, Busch A. Efficacy of different types of aerobic exercise in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R79. doi: 10.1186/ar3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stephens S, Feldman BM, Bradley N, Schneiderman J, Wright V, Singh-Grewal D, Lefebvre A, Benseler SM, Cameron B, Laxer R, O’Brien C, Schneider R, Silverman E, Spiegel L, Stinson J, Tyrrell PN, Whitney K, Tse SM. Feasibility and effectiveness of an aerobic exercise program in children with fibromyalgia: results of a randomized controlled pilot trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1399–406. doi: 10.1002/art.24115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hooten WM, Qu W, Townsend CO, Judd JW. Effects of strength vs aerobic exercise on pain severity in adults with fibromyalgia: a randomized equivalence trial. Pain. 2012;153:915–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bircan Ç, Karasel SA, Akgün B, El Ö, Alper S. Effects of muscle strengthening versus aerobic exercise program in fibromyalgia. Rheumatology international. 2008;28:527–532. doi: 10.1007/s00296-007-0484-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busch AJ, Barber KA, Overend TJ, Peloso PM, Schachter CL. Exercise for treating fibromyalgia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD003786. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003786.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kashikar-Zuck S, Flowers SR, Verkamp E, Ting TV, Lynch-Jordan AM, Graham TB, Passo M, Schikler KN, Hashkes PJ, Spalding S, Banez G, Richards MM, Powers SW, Arnold LM, Lovell D. Actigraphy-based physical activity monitoring in adolescents with juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome. J Pain. 2010;11:885–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kop WJ, Lyden A, Berlin AA, Ambrose K, Olsen C, Gracely RH, Williams DA, Clauw DJ. Ambulatory monitoring of physical activity and symptoms in fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:296–303. doi: 10.1002/art.20779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korszun A, Young EA, Engleberg NC, Brucksch CB, Greden JF, Crofford LA. Use of actigraphy for monitoring sleep and activity levels in patients with fibromyalgia and depression. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:439–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gowans SE, deHueck A. Effectiveness of exercise in management of fibromyalgia. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16:138–42. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200403000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fontaine KR, Conn L, Clauw DJ. Effects of lifestyle physical activity in adults with fibromyalgia: results at follow-up. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:64–8. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31820e7ea7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabbitts JA, Holley AL, Karlson CW, Palermo TM. Bidirectional associations between pain and physical activity in adolescents. The Clinical journal of pain. 2014;30:251–258. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31829550c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sil S, Thomas S, DiCesare C, Strotman D, Ting TV, Myer G, Kashikar-Zuck S. Preliminary evidence of altered biomechanics in adolescents with Juvenile Fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014 doi: 10.1002/acr.22450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elvin A, Siösteen AK, Nilsson A, Kosek E. Decreased muscle blood flow in fibromyalgia patients during standardised muscle exercise: a contrast media enhanced colour Doppler study. European Journal of Pain. 2006;10:137–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nijs J, Kosek E, Van Oosterwijck J, Meeus M. Dysfunctional endogenous analgesia during exercise in patients with chronic pain: to exercise or not to exercise? Pain Physician. 2012;15:ES205–ES213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staud R, Robinson ME, Price DD. Isometric exercise has opposite effects on central pain mechanisms in fibromyalgia patients compared to normal controls. Pain. 2005;118:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faigenbaum AD, Myer GD. Exercise deficit disorder in youth: Play now or pay later. Current sports medicine reports. 2012;11:196–200. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31825da961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faigenbaum AD, Stracciolini A, Myer GD. Exercise deficit disorder in youth: a hidden truth. Acta Paediatrica. 2011;100:1423–1425. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Stracciolini A, Hewett TE, Micheli LJ, Best TM. Exercise deficit disorder in youth: a paradigm shift toward disease prevention and comprehensive care. Current sports medicine reports. 2013;12:248–255. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31829a74cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simons LE, Kaczynski KJ. The Fear Avoidance model of chronic pain: examination for pediatric application. J Pain. 2012;13:827–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain. 2000;85:317–32. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sil S, Thomas S, DiCesare C, Strotman D, Ting T, Myer G, Kashikar-Zuck S. Preliminary evidence of altered biomechanics in adolescents with Juvenile Fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care & Research. doi: 10.1002/acr.22450. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, Heidt RS, Colosimo AJ, McLean SG, Van den Bogert AJ, Paterno MV, Succop P. Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes A prospective study. The American journal of sports medicine. 2005;33:492–501. doi: 10.1177/0363546504269591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paterno MV, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Rauh MJ, Myer GD, Huang B, Hewett TE. Biomechanical measures during landing and postural stability predict second anterior cruciate ligament injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport. The American journal of sports medicine. 2010;38:1968–1978. doi: 10.1177/0363546510376053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Chu DA, Falkel J, Ford KR, Best TM, Hewett TE. Integrative training for children and adolescents: techniques and practices for reducing sports-related injuries and enhancing athletic performance. Phys Sportsmed. 2011;39:74–84. doi: 10.3810/psm.2011.02.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Ford KR, Best TM, Bergeron MF, Hewett TE. When to initiate integrative neuromuscular training to reduce sports-related injuries and enhance health in youth? Curr Sports Med Rep. 2011;10:155–66. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31821b1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hewett TE, Ford KR, Myer GD. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: Part 2, a meta-analysis of neuromuscular interventions aimed at injury prevention. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:490–8. doi: 10.1177/0363546505282619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Myer GD, Brunner HI, Melson PG, Paterno MV, Ford KR, Hewett TE. Specialized neuromuscular training to improve neuromuscular function and biomechanics in a patient with quiescent juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Phys Ther. 2005;85:791–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Myer GD, Ford KR, Brent JL, Hewett TE. The effects of plyometric vs. dynamic stabilization and balance training on power, balance, and landing force in female athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20:345–53. doi: 10.1519/R-17955.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myer GD, Ford KR, McLean SG, Hewett TE. The effects of plyometric versus dynamic stabilization and balance training on lower extremity biomechanics. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:445–55. doi: 10.1177/0363546505281241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Myer GD, Ford KR, Palumbo JP, Hewett TE. Neuromuscular training improves performance and lower-extremity biomechanics in female athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19:51–60. doi: 10.1519/13643.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kashikar-Zuck S, Flowers SR, Claar RL, Guite JW, Logan DE, Lynch-Jordan AM, Palermo TM, Wilson AC. Clinical utility and validity of the Functional Disability Inventory (FDI) among a multicenter sample of youth with chronic pain. Pain. 2011;152:1600–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas SM, Sil S, Kashikar-Zuck S, Myer GD. Can Modified Neuromuscular Training Support the Treatment of Chronic Pain in Adolescents? Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2013;35:12–26. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holloway I, Todres L. The status of method: flexibility, consistency and coherence. Qualitative research. 2003;3:345–357. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Braun VCV. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palermo TM, Wilson AC, Peters M, Lewandowski A, Somhegyi H. Randomized controlled trial of an Internet-delivered family cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for children and adolescents with chronic pain. Pain. 2009;146:205–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stinson JN, McGrath PJ, Hodnett ED, Feldman BM, Duffy CM, Huber AM, Tucker LB, Hetherington CR, Tse SM, Spiegel LR, Campillo S, Gill NK, White ME. An internet-based self-management program with telephone support for adolescents with arthritis: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1944–52. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.091327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Flor H, Fydrich T, Turk DC. Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centers: a meta-analytic review. Pain. 1992;49:221–30. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]