Introduction

This paper reports the evaluation results from the first HIV prevention campaign in the U.S. focused on concurrent partnerships and HIV transmission. The project was developed using a community based participatory research (CBPR) framework in Seattle, Washington, and motivated by the need to address disparities in HIV prevalence by race. The disparate burden of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) on different racial/ethnic groups remains one of the most extreme examples of a racial inequality in health among Americans. It is substantial (1), historically persistent, especially among heterosexuals (2), begins early in life (3), and persists through the life course to older adulthood (4). In Seattle and King County, WA, White men who have sex with men (MSM) account for the majority of the HIV/AIDS caseload in total number. However, the trends in new diagnoses reflect a shifting epidemic: non-Hispanic Blacks represented 13% of new diagnoses from 1982–2003, a number that increased to 18% between 2010–2012 (5). Over one-third (39%) of Black people living with HIV in King County are members of groups born in Africa (6, 7), and the share of new cases has been rising: from 9% through 2003 to 27% in 2012 (5).

Our focus on concurrency was informed by a growing body of research findings that suggest concurrent partnerships contribute to racial disparities in HIV prevalence. Empirical studies consistently show that the disproportionate prevalence of HIV and other STIs among Blacks cannot be explained by higher rates of traditional risk behaviors (see (8) for a particularly strong example). These disparities are consistent, however, with the transmission dynamics that emerge when small differences in concurrency (overlapping sexual partnerships) are amplified by clustering in sexual partnership networks (9). Structural factors, including disproportionately high incarceration rates among Blacks in the U.S. and residential segregation establish a context within which the behavioral patterns that give rise to such networks become normative (10–13).

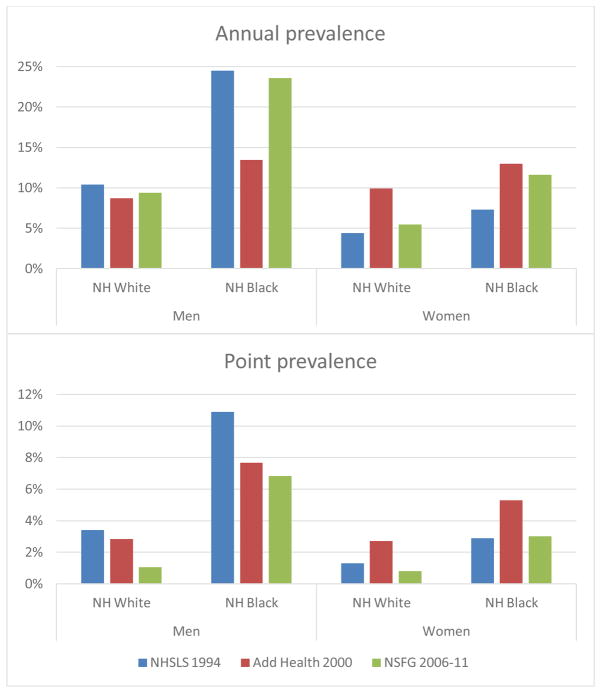

Empirical studies over the past two decades document a small but consistent differential in concurrency by race, as shown in Figure 1, especially among men. The figure shows data from three large, nationally representative surveys: the National Health and Social Life Survey (1994, age range 18–59), the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (2000, age range 18–25) and the National Survey of Family Growth (2006–11, age range 18–45). While the differences in prevalence by race are not large, studies have shown that small differences in the level of concurrency can lead to surprisingly large differences in the connectivity of the corresponding sexual transmission network (14–16). Analysis of the Add Health data has shown that the racial differentials in concurrency shown here, when combined with the observed pattern of within-group partner selection (“assortative mixing”), are sufficient to generate a threefold differential in temporal network connectivity between groups (17). This network connectivity increases the epidemic potential for all STIs, but it has a specific interaction with the infectivity profile of HIV: concurrency increases the probability of exposing another partner during the short acute stage of peak HIV infectivity. Especially in populations with low rates of partner change, a small amount of concurrency becomes the mechanism for pushing a transmission network over the threshold into the region of epidemic persistence (14), and generating a more rapid spread of infection at the outbreak (18).

Figure 1.

Survey estimates of the prevalence of concurrent partnerships by race and sex in the United States.

NH = Non-Hispanic

The data in this figure come from three different nationally representative surveys: The National Health and Social Life Survey (NHSLS, age range 18–59), The National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (Add Health, age range 17–26) and the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG, age range 18–45). Data are restricted to sexually active respondents. The prevalence measure represents the fraction of persons in each demographic subgroup who report at least two sexual partnerships in the last year that overlapped in time (i.e., were concurrent). NOTE: Annual prevalence measures the fraction of respondents who report at least one concurrent partnership in the last 12 months; point prevalence measures the fraction who have at least one concurrent partnership on the day of the interview.

If the small differences in concurrency observed in Figure 1 can have this kind of impact on disease transmission, this also presents an opportunity for prevention: we may be able to leverage equally small reductions in overlapping partnerships to catalyze a large impact on HIV prevention, and HIV disparities. This is the same concept of “herd-immunity” that is leveraged in vaccination campaigns: not everyone has to be vaccinated to end an epidemic, just enough to bring transmission below the threshold of persistence (19). This recognition has led to the development of many innovative HIV prevention media campaigns on concurrency in sub-Saharan Africa (those developed by Population Services International may be viewed here: http://cptoolkit.hivsharespace.net/pages/4-mass-media.html). As described in a previous paper (20) it also inspired the “Community Action Board” (CAB) of the University of Washington (UW) Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) to partner with researchers and local Public Health officials to develop this project to assess the feasibility and acceptability of concurrency messaging for HIV prevention in the Black community in Seattle and King County, Washington. The project piloted a multifaceted grassroots and local media social marketing campaign. The campaign sought to educate Black individuals living in Seattle and King County about local HIV incidence and prevalence, existing HIV disparities, and the link between concurrent sexual partnerships and HIV transmission. It did not seek to prescribe a specific behavioral change, but instead to inform and to start a discussion within the community about the unique risks that concurrency poses for STI and HIV transmission. This article presents the results from the post-campaign evaluation survey on the acceptability of the message, and describes some of the challenges experienced during the process.

Methods

The overall project involved a multi-year CBPR process, though the campaign itself was quite short (3 months). Many aspects of this process have been reported in a previous paper (20), but we summarize them here, as the feasibility and acceptability of this intervention is based on this process.

Community involvement began with a day-long workshop on Racial Disparities in HIV, where members of the UW CFAR CAB heard several scientific presentations that focused on different aspects of the problem (one of these presentations focused on concurrent partnerships) and the local public health department presented local data on HIV prevalence and incidence by race, sex, ethnicity and national origin. The second half of the workshop was devoted to breakout discussions to decide which topics (if any) the CAB wanted to pursue. Enough members were interested in focusing on concurrency that a collaborative working group was formed (including researchers, CAB members, and local Public Health staff). The working group developed a successful NIH R21 grant proposal to establish the feasibility and acceptability of translating the scientific information on concurrency and HIV transmission into a set of culturally sensitive and relevant themes and materials for the local African American and African-Born communities. Local CBOs delegated representatives to work on the project, and half of the grant funding supported their efforts. These representatives were trained in qualitative methods, helped to design and implement a set of focus groups and in-depth interviews to come up with possible message themes, solicited proposals from and selected a media firm to create the message, and refined the materials the firm created.

The campaign was originally conceived as a mass-media campaign, to appear as public service announcements on busses and trains in the area. However, Clear Channel, the advertising company we originally contracted with, controlled those outlets, and they refused to carry the ads the community had designed. The working group then decided on an alternative plan: a three-month grassroots and public media campaign, involving palm cards, flyers in local business windows, ads in ethnic newspapers, and a couple of spots on local public radio and community cable channels. The flyers and palm cards were distributed in predominantly African American neighborhoods with high rates of HIV. These neighborhoods had been selected using U.S. census data to identify zip codes with greater than 3,000 Black residents (19) and Public Health Seattle & King County data (6) to identify zip codes with high HIV incidence and prevalence. In total, 21 zip codes were selected.

This grassroots campaign was implemented from July 2011 through September 2011. One month after the campaign ended, working group members conducted a street intercept survey using a self-administered questionnaire on a handheld personal digital assistant (PDA) to evaluate the reach, acceptability and preliminary efficacy of the campaign.

Street intercept survey design

We used a street intercept survey with a target sample size of 125, stratified by sex, sexual orientation and country of origin (U.S. vs. other). Street intercepts have been shown to be feasible and acceptable in Black communities (21), and they provided this project with a cost-effective method for interviewing a sample of persons who could have been exposed to the materials in the neighborhoods where the campaign was implemented. The community members of the working group were divided into three teams of interviewers and assigned to the campaign neighborhoods to conduct evaluation activities. Two interview teams included one African American and one African-Born person and a field supervisor. One interview team focusing on predominantly African-Born communities included 2 multilingual African-Born persons and a field supervisor. All interview team members had worked on the project from the beginning, so they had received training in the goals of the project, the message, the campaign materials and the research methods.

Interviews were conducted over a 10-day period in October 2011. Interviewer teams made a minimum of one visit to multiple locations in each of the identified zip codes. Locations and visit times were purposively selected based on the volume of pedestrian traffic. During visits, team members approached Black individuals and conducted a brief eligibility screen. Eligibility criteria included: a) residing in Seattle/King County; b) identifying as Black, African, or African American; c) born in the United States or Africa; and d) 18 years of age or older. Eligible participants were asked if they would like to participate in a 5-minute survey to provide feedback on HIV prevention messages created by and for the Black community and told that they would be paid $20 for their time. Due to the brief nature of street intercepts, written documentation of consent was waived. Information about the study was supplied on the PDA device and either read to or by each participant, after which oral consent was obtained. A hard copy of this study information was also provided to each participant. PDA evaluations were confidential and anonymous with no recording of names or personal identifiers. Human Subjects approval was obtained at the University of Washington (HSD #34436).

Self-administered PDA survey

We chose this technology because it has the dual advantages of collecting potentially sensitive data with consistent fidelity and less social desirability bias (SDB) (22). After obtaining consent from the participant, the community educator demonstrated the correct use of the PDA by assisting with initial demographics questions (i.e., age, race, sex). To ensure confidentiality and decrease SDB, the PDA was then handed to the participant for completion of the remaining demographic questions, which included country of origin, sexual orientation, whether they had sex with men, HIV status, monthly income and current labor force status.

After the collection of demographic information the interviewer asked participants if they remembered seeing any advertising about sexual behavior and HIV in the newspaper or on a flyer or palm card in the community in the last three months. Participants were then shown a campaign palm card (the “campaign materials”) and asked if they had seen any of the campaign materials during the last three months in King County. Participants were shown only the concurrency materials used in this campaign. All participants answered three Likert-scale questions assessing perceptions of HIV as a problem for the local Black community, perceived own STI risk, and feelings of responsibility for the health of one’s community.

Participants who indicated seeing the campaign materials then completed the remaining items in the PDA evaluation. The evaluation components and questions were selected by the working group members, after review and discussion of recently published papers that reported evaluations of health information campaigns focused on smoking, drinking and sexual behavior (23–27). The selected items were designed to assess the reach, acceptability, and impact of the concurrency campaign:

Reach: We examined the overall reach of the campaign, using the answer to the question about exposure to the campaign materials, and source-specific reach. We utilized Hornik and Yanovitzky’s (28) general theory of effects as a guide for assessing the reach of the campaign through direct exposure and social diffusion (social interactions with friends, peers, family, and community members). Four questions assessed participant exposure to the ads, using a prompted list to elicit through what medium, and how often, the participant had seen the messages.

Acceptability: Acceptability was assessed on several dimensions, including the content of the message, and the quality of the campaign materials. Five Likert-scale questions asked participants to rate the ads in terms of visual attractiveness, how interesting they were, the importance of the message to the participant, the importance for the community, and their overall response to the materials.

Impact: As a pilot, this study was not designed to provide an evaluation of efficacy, but we did seek to establish preliminary evidence of efficacy through self-reported impact of the campaign on knowledge, attitudes and behavior. Three Likert-scale questions assessed the self-reported impact of the campaign on concurrency related knowledge (How much did the ad campaign impact your knowledge about concurrency and HIV/AIDS?), attitudes (How did the ads affect your attitude about concurrency?), and behavior change intentions (How likely are you to change your current behavior because of the ads?)

Data Analysis

Responses were analyzed by sample stratification group: a 5 category classification defined by gender (M vs. F), place of birth (U.S. vs. Africa) and MSM status for men. We coded the one participant who chose “Transgender” as MSM based on self-identification as homosexual or gay and having sex with men. For graphical presentation, we collapsed the two lower and the two upper categories of the Likert-scale variables to create a 3 level ordinal variable: negative, moderate/neutral and positive. To facilitate assessment of the significance of differences across evaluation groups, categories were collapsed to create a two-level contrast. Because we were most concerned with negative responses to the campaign, we collapsed the “neutral” category with the two positive categories when possible. For the evaluation questions, however, the number of negative responses in the lower two categories were so few (ranging from 4 to 7 persons) that we needed to collapse the neutral category with the negatives to obtain a sufficient number of cases for testing the cross-group differences. Some cells in the cross-group comparisons still contained less than 5 observations, so we use Fisher’s exact test to assess significance. Descriptive statistics (frequencies and cross-tabulations) were conducted using SPSS; statistical tests were conducted in R. Community members from the working group were involved in reviewing the preliminary results, provided comments, made presentations in various settings, and contributed to this paper.

Results

A total of 129 persons were approached; 116 of these met the eligibility criteria and provided demographic information via the PDA. The characteristics of the sample are shown in Table I. Over 91% of respondents remembered seeing any advertisements about HIV and sexual behavior in the previous three months, and most respondents (82%) reported they had seen the campaign materials when prompted with the campaign flyer and palm cards. There were no statistically significant differences in campaign exposure by evaluation group (shown in Table II).

Table I.

Sample characteristics

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 116 | 100.0 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 74 | 63.8 |

| Female | 39 | 33.6 |

| Other | 3 | 2.6 |

|

| ||

| Age | ||

| 18–24 yrs | 35 | 30.2 |

| 25–29 yrs | 30 | 25.9 |

| 30–39 yrs | 28 | 24.1 |

| >40 yrs | 23 | 19.8 |

|

| ||

| National Origin | ||

| United States | 59 | 50.9 |

| African-born | 57 | 49.1 |

|

| ||

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 86 | 74.1 |

| Homosexual/Gay | 25 | 21.6 |

| Bisexual | 4 | 3.4 |

| Other | 1 | 0.9 |

|

| ||

| Has sex with men | ||

| No | 48 | 41.4 |

| Yes (Men) | 28 | 24.1 |

| Yes (Women) | 40 | 34.5 |

|

| ||

| Monthly Income | ||

| $1,250 or less | 47 | 40.5 |

| $1,251–$2,500 | 34 | 29.3 |

| $2,500+ | 24 | 20.7 |

| Refused/DK | 11 | 9.5 |

|

| ||

| Employment Status | ||

| Full time | 66 | 56.9 |

| Part time | 22 | 19.0 |

| Not working | 28 | 24.1 |

|

| ||

| Student Status | ||

| Full time | 10 | 8.6 |

| Part time | 7 | 6.0 |

| Not a student | 99 | 85.3 |

|

| ||

| Evaluation Group | ||

| Male, Heterosexual, US | 14 | 12.1 |

| Male, Heterosexual, African | 34 | 29.3 |

| Male, MSM, US | 28 | 24.1 |

| Female, US | 17 | 14.7 |

| Female, African | 23 | 19.8 |

|

| ||

| Campaign exposure | ||

| No exposure reported | 10 | 8.6 |

| General exposure | 11 | 9.5 |

| Recognized campaign material | 95 | 81.9 |

Table II.

Campaign results by evaluation group.

| Men | Women | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Heterosexual | MSM

|

African American | African born | Fisher’s exact p-value | |||

|

|

|||||||

| African American | African born | African American | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Saw the campaign materials | 78.6 | 82.4 | 89.3 | 70.6 | 82.6 | 81.9 | 0.609 |

| Agree that: | |||||||

| HIV is a problem for the local Black Community | 78.6 | 78.8 | 88.9 | 80.0 | 87.0 | 83.0 | 0.798 |

| I feel responsible for the health of my community | 78.6 | 100.0 | 85.2 | 66.7 | 95.7 | 88.4 | 0.002 |

| I am likely to get an STI or HIV in the next 6 mos | 28.6 | 33.3 | - | 20.0 | 13.0 | 18.8 | 0.005 |

| Exposed to Campaign Materials (N=95) | |||||||

| Reached at least once by: | |||||||

| Social Network | 63.6 | 100.0 | 64.0 | 83.3 | 78.9 | 80.0 | 0.002 |

| Street Poster | 63.6 | 57.1 | 80.0 | 83.3 | 47.4 | 65.3 | 0.107 |

| Business | 54.5 | 57.1 | 40.0 | 50.0 | 89.5 | 57.9 | 0.015 |

| Newspaper | - | 21.4 | 16.0 | 16.7 | 21.1 | 16.8 | 0.600 |

| TV | 9.1 | - | 4.0 | 16.7 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 0.156 |

| Web | - | 3.6 | 8.0 | 8.3 | - | 4.2 | 0.656 |

| Positive evaluation of: | |||||||

| Visual appeal | 72.7 | 82.1 | 83.3 | 100.0 | 94.7 | 86.0 | 0.281 |

| Interesting | 81.8 | 89.3 | 91.7 | 90.9 | 100.0 | 91.4 | 0.440 |

| Important to you | 81.8 | 82.1 | 95.8 | 100.0 | 94.7 | 90.3 | 0.285 |

| Important to community | 90.9 | 85.7 | 94.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 93.2 | 0.369 |

| Overall | 81.8 | 85.7 | 91.7 | 90.9 | 100.0 | 90.3 | 0.369 |

| Moderate or larger impact of campaign on: | |||||||

| Knowledge about concurrency | 81.8 | 89.3 | 70.8 | 100.0 | 84.2 | 83.7 | 0.266 |

| Attitude towards concurrency | 63.6 | 78.6 | 66.7 | 100.0 | 84.2 | 77.2 | 0.177 |

| Behavior change intention | 54.5 | 78.6 | 33.3 | 80.0 | 84.2 | 65.2 | 0.002 |

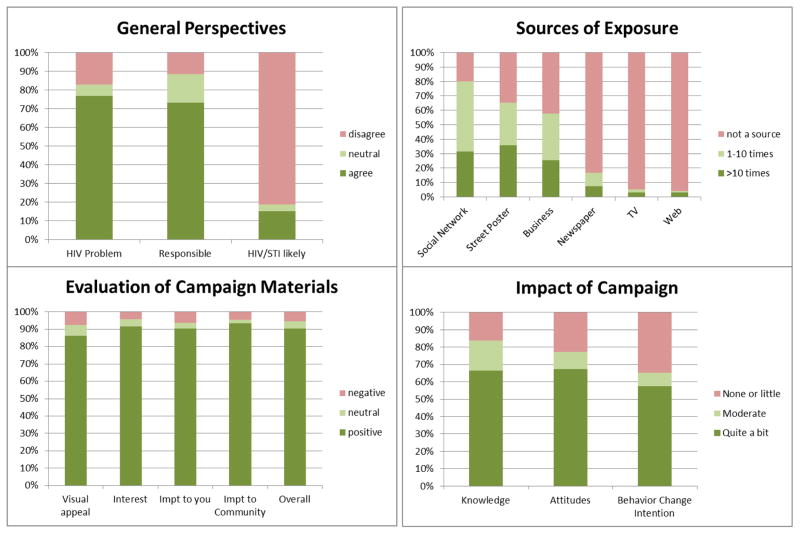

The overall responses to all questions are shown in Figure 2, with subgroup breakdowns in Table II. Over 76% of all respondents agreed that HIV was a problem for the local Black community, with no significant differences between subgroups. About 73% of all respondents said that they felt responsible for the health of their community, but here significant differences emerged. African-Born men and women were most likely to agree with this statement, while African American heterosexual men and women were less likely to agree (p < 0.01). The perception of personal risk was relatively low: only 15% of all respondents reported it likely that they would get an STI or HIV in the next six months. But again there were significant differences by subgroup. None of the African American MSM reported it was likely, compared to 29–33% of heterosexual men, and 13–20% of women (p < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Overall survey responses

Turning now to those who remembered seeing the campaign materials (n=95), there were large differences in the sources of exposure. The single most common source of exposure was social networks: 80% of these respondents reported that they had heard about the campaign from another person in the last month, and 32% of these reported that these discussions were frequent. Almost everyone who reported social network exposure reported discussing the campaign materials with friends (95%); discussions with co-workers (12%) and family members (7%) were much less common. There were significant differences in social network exposure by subgroup, with African-Born men most likely to report any discussions (100%), both groups of African American men least likely (64%), and the two groups of women in between at about 80% (p < 0.01). It is important to note that no African-Born men self-identified as gay or homosexual or reported sex with men. The next most common source of exposure was seeing the flyers in the streets (65%) or in a local business (58%). There were no significant subgroup differences in street exposure, but business exposure did differ: almost 90% of African-Born women reported seeing the campaign materials in a business, compared to 40% of African American MSM (p < 0.05). By contrast, exposure via any of the mass media outlets was much less common: few respondents reported seeing the campaign materials in the newspaper (17%), on the TV (5%) or on the Web (4%). This despite the fact that the study materials had been published repeatedly in community specific papers, the study PI had made numerous appearances on the local African-Born cable TV channels and on an African American morning radio program, and quite a bit of effort had been put into building a website, the url of which was included on all printed materials (www.stopconcurrency.org). During the campaign, the website received 409 visits with 57 (13.9%) return visits. Unfortunately, it is impossible to distinguish visits by community members from those made my individuals associated with the research project.

Evaluation of the campaign materials was strongly and consistently positive, for all aspects, and across all subgroups. Over 85% of respondents found the materials very visually attractive, and over 90% found them very interesting, very important both for themselves and for their community, and had an very positive overall response. There were no significant differences in positive evaluation by subgroup.

The self-reported impact of the campaign was also strong and positive. Over 80% of respondents said the campaign had increased their knowledge about concurrency, and over 75% reported that it had changed their attitude towards concurrency. There were no significant differences between the groups, though it is worth noting that 100% of African American women responded that the campaign had increased their knowledge and changed their attitudes. The campaign impact on behavior change intention was somewhat lower, but a respectable 65% of respondents reported they were somewhat to very likely to change their behavior as a result of the campaign. This is the only campaign impact that showed significant differences by subgroup: only one-third of African American MSM said it was likely their behavior would change, compared to 54% of African American heterosexual men, and about 80% of the other three groups (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The posttest survey demonstrated the acceptability of a community-developed concurrency information campaign within African American and African-Born communities of Seattle. The results show that this inexpensive grassroots campaign had remarkably good reach, with 82% of respondents reporting that they remembered seeing the campaign materials, and no significant difference by subgroup. Local community exposure (flyers posted on the streets and in businesses) turned out to be much more effective than the mass media (newspaper, TV and web) in reaching people. Most importantly, however, the campaign moved beyond individual exposure and entered into social networks, with 80% of those who saw the materials reporting that they had heard about and discussed the campaign with their friends, co-workers and family members. All subgroups evaluated the campaign materials positively: as very visually attractive (85%), very interesting (91%) and very important for themselves (90%) and for their community (93%). The self-reported impacts of the campaign were also strong and positive, with 85% saying the campaign had increased their knowledge about concurrency, 77% saying it changed their attitudes, and 65% saying it was likely or very likely that they would change their behavior as a result.

The survey did reveal some heterogeneity by subgroup that was interesting and informative. African-Born community members were most likely to report feeling responsible for the health of their community, and to have discussed the campaign with members of their social network. African American MSM were least likely to perceive themselves at risk for an STI or HIV in the next six months, among the least likely to have discussed the campaign with members of their social network, and the least likely to say that the campaign had influenced them to change behavior. The heterosexual men, both African American and African-Born, were the most likely to perceive themselves at risk for an STI or HIV in the next 6 months. The differences do not consistently line up with sex, sexual orientation, or national origin, but instead cut across these lines for different elements of the response to the campaign. Still, it is worth emphasizing that all groups, without exception, reported very positive evaluations of the campaign.

Limitations

This pilot study was designed primarily to evaluate acceptability of a concurrency information campaign implemented through CBPR, a goal adequately assessed through a simple post-exposure design with a relatively small sample. We did not implement a full pretest-posttest approach to evaluating the campaign impact. The use of a posttest-only design is generally considered to be a weak outcome evaluation design as it does not control for threats to internal validity (29). The threats are not relevant for the evaluation results addressing acceptability and reach, but are for the assessment of impact. Our impact findings can be interpreted as preliminary evidence that a campaign of this sort may be effective in changing knowledge, attitudes and behavioral intentions, but a more rigorous design would be required to demonstrate efficacy. The street intercept quota sample may not be representative, and our small sample size limited our ability to identify significant differences between groups.

Our survey did not ask respondents about their own behavior, or about what type of behavior they intended to change if they said the campaign influenced them to change behavior. Our broad messaging approach focused on raising awareness, not on prescribing a specific behavioral change. Note that there are several possible behavioral responses that would be responsive to a campaign focused on concurrency: not engaging in concurrent partnerships, using condoms in concurrent partnerships, discussing the topic with a partner whose concurrency puts you at risk, and discussing the topic with friends and family to spread the information. To evaluate the efficacy and effectiveness of this type of campaign, future studies should include questions assessing these specific behaviors pre- and post-campaign.

Participant recall bias may have influenced the accuracy of recollections of the campaign materials, and our measure of the overall reach of the campaign. Future studies could include materials that were not part of the actual campaign to assess this. Another potential threat to validity is social desirability bias (SDB): in particular, survey respondents may feel obliged to give positive evaluations to the campaign elements. While there is some danger of this in any survey, we feel the problem is not likely to be large here for two reasons. First, the survey was completed anonymously and confidentially by the respondents on the PDAs as a self-administered questionnaire. This provides a level of privacy that has been shown to reduce SDB (cf. the review in 30). Second, we observed a notable lack of SDB in the measures of campaign impact. Respondents clearly felt comfortable reporting if the campaign did not change their knowledge, attitudes, behavior (16%, 23% and 35% respectively). Perhaps most striking here is the pattern observed for MSM: while they provided slightly more positive evaluations of the campaign elements than the heterosexual men, they were also the least likely to report impact: 29% said it had no impact on their knowledge, 33% no impact on their attitudes, and 67% no impact on their behavioral intentions. There was anecdotal evidence reported by research staff that the absence of perceived STI risk and lower behavior change intentions among MSM reflect their having already adopted safer sexual behaviors. However, what we measured is self-reported perception of risk, not objective risk. In interpreting the behavioral intention results for MSM it is also worth remembering that the herd immunity rationale for focusing on concurrency: not everyone needs to change behavior for the change to be effective. Here, one-third of MSM reported the intention to change behavior. That may not be evidence of high efficacy, but it does indicate a potential for change that could be effective at the population level.

One final issue is worth reviewing in some detail: dealing with the potential backlash to a campaign like this. There are sensitivities in any public health campaign that addresses sexual behavior, but the intersection of race, sexual orientation and immigration on top of a sexual theme was a particularly volatile mix. The original implementation design for this study relied entirely on mass-media advertising: primarily ads on local public transit, but also local newspaper, TV and the web. We were unable to place the ads on public transit because Clear Channel, the organization that controls this venue, refused to accept the ads (claiming they were “lewd and lascivious”). This necessitated a change in strategy, and led to the intensive grassroots campaign distributing flyers and palm cards. During the implementation phase of our project, reservations were also voiced by a few community members – some in the local public press (see: http://preview.tinyurl.com/mfkbbov and http://preview.tinyurl.com/kussc4c) and some directly to the study PI via email or phone call. The two main concerns raised were that the campaign was stigmatizing, and that it was imposed in a racially insensitive way by the white community onto various minority communities. The study PI carefully responded to all of these concerns when they arose, and undertook some pro-active efforts in the local media to make it clear that this was a campaign developed by local minority community members, for their communities. The personal interactions were particularly important in gaining acceptance and willingness to host materials by local businesses and community colleges. In retrospect, these issues would probably have been more difficult to defuse had these posters ended up on public transit as originally planned. Given that all of the personal feedback the PI received during implementation was negative, it was profoundly surprising to find the very strong positive evaluation of the campaign materials by the community members who participated in this street intercept survey.

Given these experiences, we believe there are two broader generalizable findings from this study. The first is that there may be a substantial discrepancy between public gatekeepers and community members in the evaluation of a public health message: while both Clear Channel and a few external activists objected to the message of our campaign (publicly and loudly), and some business owners needed to be convinced to post the materials, over 90% of the community it was intended for found the campaign acceptable, interesting and important. The second is that the process is as important as the information. This has important implications for the dissemination of our campaign materials. While our materials can be used as a starting place for a CBPR process in another community, they should probably not be used as a basis for a top-down campaign. It is critical to develop reciprocal relationships between community and academic partners to establish community ownership of the development of a message like this. Our process cannot replace the process that must be undertaken in each community. This extends to the message channel itself: a targeted, low-tech grassroots campaign may be more likely to establish the trust needed to start a productive community conversation than a broadcast media campaign. This is a different avenue of health communication, but an old idea: the medium is (part of) the message.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) grant number 5R21 HD057832-02 (to Dr. Andrasik). This publication resulted in part from research supported by the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI027757), which is supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers (NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NIA). We would like to sincerely thank our community members for their vision, guidance, and contributions. A special thanks to the Center for Multicultural Health for their ongoing partnership and collaboration.

Contributor Information

Michele Peake Andrasik, Email: mpeake@u.washington.edu, Acting Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Washington, Box 358080, Behavioral Scientist, HIV Vaccine Trials Network, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Avenue N, LE-500, Seattle, WA 98109-1024, (206) 667-2074, Fax (206) 667-6366

Rachel Clad, Email: rclad@live.unc.edu, Research Coordinator, Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Joanna Bove, Email: bovej@uw.edu, Sociobehavioral and Prevention Research Core (SPRC) UW/FHCRC Center for AIDS Research, Seattle, WA.

Solomon Tsegaselassie, Email: solomont@cschc.org, Center for Multicultural Health, Seattle, WA.

Martina Morris, Email: morrism@uw.edu, Departments of Sociology and Statistics, University of Washington, Sociobehavioral and Prevention Research Core, UWCF, CSDE, CFAR, Seattle, WA.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disparities in Diagnoses of HIV Infection Between Blacks/African Americans and Other Racial/Ethnic Populations — 37 States, 2005–2008. MMWR. 2011;60(4):93–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) among blacks and Hispanics---United States. MMWR. 1986;35:655–66. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris M, Handcock MS, Miller WC, et al. Prevalence of HIV infection among young adults in the U.S.: Results from the ADD Health study. Amer J Pub Health. 2006 Jun;96(6):1091–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV Infection among Adults Aged 50 Years and Older in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2013;18(3) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Public Health Seattle & King County & Infectious Disease Assessment Unit WSD. HIV AIDS Epidemiology Report. Second Half. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Public Health Seattle & King County. Facts about HIV/AIDS Among Foreign-Born Blacks. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Public Health Seattle & King County. King County data from the National HIV surveillance system. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ, Miller WC, Bauer DJ. Sexual and drug behavior patterns and HIV and STD racial disparities: The need for new directions. Am J Public Health. 2007 Jan;97(1):125–32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris M, Kurth AE, Hamilton DT, Moody J, Wakefield S. Concurrent partnerships and HIV prevalence disparities by race: linking science and public health practice. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):1023–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.147835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adimora A, Schoenbach V, Doherty I. HIV and African Americans in the southern United States: Sexual networks and social context. SexTransm Dis. 2006;33(Supplement 7):S39–S45. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000228298.07826.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adimora A, Schoenbach V. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(Supplement 1):S115–S22. doi: 10.1086/425280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Taylor EM, Khan MR, Schwartz RJ, Miller WC. Sex ratio, poverty, and concurrent partnerships among men and women in the United States: a multilevel analysis. Ann of Epidemiol. 2013 Nov;23(11):716–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan M, Doherty I, Schoenbach V, Taylor E, Epperson M, Adimora A. Incarceration and high-risk sex partnerships among men in the United States. J Urban Health. 2009;86(4):584–601. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9348-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodreau SM, Cassels S, Kasprzyk D, Montano DE, Greek A, Morris M. Concurrent Partnerships, Acute Infection and HIV Epidemic Dynamics Among Young Adults in Zimbabwe. AIDS Behav. 2012 Feb;16(2):312–22. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9858-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris M, Goodreau S, Moody J. Sexual Networks, Concurrency, and STD/HIV. In: Holmes KK, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit JN, Corey L, et al., editors. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 4. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris M, Kretzschmar M. A Micro-simulation study of the effect of concurrent partnerships on HIV spread in Uganda. Math Pop Studies. 2000;8(2):109–33. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodreau S, Kitts J, Morris M. Birds of a Feather, or Friend of a Friend? Using Statistical Network Analysis to Investigate Adolescent Social Networks. Demography. 2009;46(1):103–25. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powers KA, Ghani AC, Miller WC, et al. The role of acute and early HIV infection in the spread of HIV and implications for transmission prevention strategies in Lilongwe, Malawi: a modelling study. Lancet. 2011;378:256–68. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60842-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fine P, Eames K, Heymann DL. “Herd Immunity”: A Rough Guide. Clin Infect Dis 2011. 2011 Apr 1;52(7):911–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrasik M, Chapman C, Clad R, et al. Developing Concurrency Messages for the Black community in Seattle, WA. AIDS Educ Prev. 2012;24(6):527–48. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.6.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller K, Wilder L, Stillman F, Becker D. The feasibility of a street-intercept survey method in an African-American community. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(4):655–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.4.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tourangeau R, Yan T. Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychol Bull. 2007 Sep;133(5):859–83. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Darrow W, Biersteker S. Short-Term Impact Evaluation of a Social Marketing Campaign to Prevent Syphilis Among Men Who Have Sex with Men. Am J Public Health. 2006;98(2):337–43. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.109413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donna M, Vallone JN, Richardson AK, Patwardhan P, Niaura R, Cullen J. A National Mass Media Smoking Cessation Campaign: Effects by Race/Ethnicity and Education. Am J Health Promot. 2011;25(5 Supplement):S38–S50. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.100617-QUAN-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perkins HW, Linkenbach JW, Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Effectiveness of social norms media marketing in reducing drinking and driving: A statewide campaign. Addict Behav. 2010;35:866–74. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertrand JT, Goldman P, Zhivan N, Agyeman Y, Barber E. Evaluation of the “Lose Your Excuse” Public Service Advertising Campaign for Tweens to Save Energy. Eval Rev. 2011;35(5):455–89. doi: 10.1177/0193841X11428489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans WD, Davis KC, Umanzor C, Patel K, Khan M. Evaluation of Sexual Communication Message Strategies. Reprod Health. 2011;8(15) doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hornik R, Yanovitzky I. Using Theory to Design evaluations of communication campaigns: The case of the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign. Commun Theory. 2003;13(2):204–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2003.tb00289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-experimentation: design & analysis issues for field settings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krumpal I. Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: a literature review. Quality & Quantity. 2013 Jun;47(4):2025–47. [Google Scholar]