Abstract

Antagonistic Streptomyces spp. AJ8 was isolated and identified from the Kovalam solar salt works in India. The antimicrobial NRPS cluster gene was characterized by PCR, sequencing and predict the secondary structure analysis. The secondary metabolites will be extracted from different organic solvent extraction and studied the antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral and anticancer activities. In vitro antagonistic activity results revealed that, Streptomyces spp. AJ8 was highly antagonistic against Staphylococcus aureus, Aeromonas hydrophila WPD1 and Candida albicans. The genomic level identification revealed that, the strain was confirmed as Streptomyces spp. AJ8 and submitted the NCBI database (KC603899). The NRPS gene was generated a single gene fragment of 781 bp length (KR491940) and the database analysis revealed that, the closely related to Streptomyces spp. SAUK6068 and S. coeruleoprunus NBRC15400. The secondary metabolites extracted with ethyl acetate was effectively inhibited the bacterial and fungal growth at the ranged between 7 and 19.2 mm of zone of inhibition. The antiviral activity results revealed that, the metabolite was significantly (P < 0.001) controlled the killer shrimp virus white spot syndrome virus at the level of 85 %. The metabolite also suppressed the L929 fibroblast cancer cells at 35.7 % viability in 1000 µg treatment.

Keywords: Antimicrobial, Haloalkaliphils, Non ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS), Streptomyces spp. AJ8

Introduction

Microbes from extreme environments have attracted considerable attention in recent years. This is primarily due to the secret that they hold about the molecular evolution of life and stability of the macromolecules. Majority of the studies on extremophilic organisms, however, have been confined to extremophilic bacteria and actinomycetes are relatively less explored group (Vasavada et al. 2006). Extreme environments are populated by groups of organisms that are specifically adapted to these particular conditions and these types of extreme micro-organisms are usually referred to as alkaliphiles, halophiles, thermophiles and acidophiles, reflecting the particular type of extreme environment which they inhabit (Horikoshi 1991). Study of extremophilic actinomycetes and identification of their metabolic properties are most important tasks in biotechnology (Vinothini et al. 2008).

Solar salterns are unique hypersaline environments, characterized by their high salt concentration and alkaline pH (Zafrilla et al. 2010). They are the important class of microbial resources and important producers of secondary metabolites including antimicrobials. Recent reports have revealed that salt requiring microbes are a robust source of new natural products and serve as model systems in drug discovery (Fencial 1997). Several actinomycetes, found to be proficient to produce antimicrobial compounds and halotolerant enzymes, have been reported from the coastal solar salterns (Vasavada et al. 2006; Aruljose et al. 2011). Actinomycetes are the most economically and biotechnologically valuable prokaryotes (Lam 2006) On the other hand, a great metabolic diversity and biotechnological potential has been found in halophilic and halotolerant microorganisms. Streptomyces are especially prolific and can produce a great many antibiotics (around 80 % of the total antibiotic production) and active secondary metabolites (Remya and Vijayakumar 2008).The past several decades many laboratories have conducted a vast screening effort to isolate secondary metabolites with interesting biological activities (Manivasagan et al. 2013). It is accepted that halophilic actinomycetes will provide a valuable resource for novel products of industrial interest, including antimicrobial, cytotoxic, neurotoxic, antimitotic, antiviral and antineoplastic activities (Cragg and Newman 2005).

In the realm of drug discovery, important new metabolites with biological activities have been and are still being discovered from actinomycetes and many of these are described as being produced by polyketide synthases (PKS) and NRPS. Nonribosomally synthesized peptides represent a large group of structurally complex metabolites that are manufactured from amino, hydroxy and carboxy acid monomers by large multifunctional enzymes, termed NRPS (Mootz and Marahiel 1997). They are modular mega-multifunctional enzymes that synthesize an incredibly diverse set of biological active peptides or cyclic lipopeptides (Schwarzer et al. 2003). They are antibiotics, biosurfactants, siderophores, and immunosuppressant, as well as antitumor and antiviral agents. These valuable biomolecules carry important medical and biotechnological applications (Roongsawang et al. 2005). The present study intends to the identification, NRPS characterization and the pharmacological influence of haloalkaliphilic Streptomyces spp AJ8 which isolated from solar salt works.

Materials and methods

Isolation of haloalkaliphilic Streptomyces

Mud sediments (depth 5 cm; salinity 260 ‰ & pH 10.5) was collected from the condenser pond of the solar salt works of Kovalam, Kanyakumari, Tamilnadu, India (8°05′04.35″N 77°31′17.07″E) during the summer season of May 2013. Ten grams of mud soil samples were suspended in 100 ml of sterile water and 0.1 ml of suspension from this was spread over 10 % NaCl concentration on Knight’s agar media (pH 7.2) and incubated at 28 °C for 2–3 weeks. The isolates was sub-cultured and maintained in slant culture at 4 °C as well as at 20 % (v/v) glycerol stock at −80 °C for future use.

Preliminary in vitro antagonistic activity

Preliminary screenings of antagonistic activity were done by the method described by Shomurat et al. (1979) against pathogenic bacteria and fungi. The haloalkaliphilic actinomycetes strains were spot inoculated in starch casein agar medium for 4 days. After 4 days, then they were overlaid with 5 ml of sloppy agar (0.6 %) layer previously seeded with anyone of the test microbes, bacteria and fungi. Further this was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and the diameter of the incubation zone was recorded in millimetres.

Phenotypic identification and cultural characteristics

Based on the antagonistic activity, the best haloalkaliphilic actinomycetes strain was undergo the biochemical characterization following the International Streptomyces Project (ISP) procedures (Shimizu et al. 2000). The physiological characteristics of the isolates such as, growth at different pH (5.5, 6 0.5, 7.5, 8.5, 9.5 and 10.5), NaCl concentration (2, 4, 6, 8 and 10) were recorded in starch casein broth. A set of cultural characteristics was also examined using media and the ISP procedures recommended by Shirling and Gottlieb (1966). Mature aerial mycelium and substrate mycelium pigmentation were recorded on Starch casein agar media following incubation at 28 °C for 28 days.

Genomic identification

One hundred nanogram of genomic DNA was isolated from Streptomyces spp. AJ8 and amplified by PCR using 16S rRNA universal primers. The PCR product was cloned into the vector pTZ57R and used to transform Escherichia coli DH5α. The transformants were sequenced using an ABI 3700 automated DNA sequencer. Sequences were compared with other 16S rRNAs obtained from GenBank using the BLAST program. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by Geneious 5.4.6 software and evolutionary history was inferred using the UPGMA method. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method (Arif et al. 2011) and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site.

PCR amplification of biosynthetic cluster gene NRPS

NRPS gene was amplified from the genomic DNA template of Streptomyces spp. AJ8 using the degenerate primer oligonucleotides sets namely A3: (5′GCSTACSYSATSTACACSTCSGG3′) and A7R: (5′SASGTCVCCSGTSCGGTAS3′). PCR reactions were performed in a final volume of 50 µl containing 10 % of extracted DNA, 0.4 µM of each primer, 0.2 mM of each of the four dNTPs, 5 µl extracted DNA, 1 U Taq polymerase with its recommended reaction buffer, and 10 % DMSO. PCR parameters were 95 °C for 5 min of initial denaturation, 95 °C for 30 s of denaturation, 59 °C for 2 min of annealing, 72 °C 4 min and 72 °C of 10 min for final elongation on Eppendorf Mastercycler personal, Germany. The PCR products were resolved in 1 % (w/v) agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide.

Sequencing and database analysis

The PCR product was purified by using gel extraction kit (Medox Biotech India Pvt. Ltd.) and sequenced using an ABI 3700 automated DNA sequencer by M13+ and M13− primers (Sambrook et al. 1989). Sequences were compared with other NRPS gene obtained from GenBank using the BLAST program. Nucleotide sequence alignment and identity was analysed by using Clustal X (1.8.1) software (European Bioinformatics Institute).The phylogenetic tree was constructed by Geneious 5.4.6 software and tree build by using the UPGMA method and the genetic distance calculated using Tamura-Nei method (Sneath and Sokal 1973).

NRPS protein structure prediction analysis

In order to study the secondary structure and functional prediction, Iterative Threading Assembly Refinement (I-TASSER) online bioinformatics software was used. This algorithm modeled and worked based on LOMETS multiple-threading alignment and TASSER iterative simulation. I-TASSER server results predict accurate structure and function base on state-of-the-art algorithm. This server was ranked as No 1 server proved by current CASP7 and CASP8 experiment (Roy et al. 2010; Zhang 2008). After run the sequence in the protein 3D structure was downloaded and visualized using molecular visualization tools of RasMol. Quality of the predicted protein models was estimated using C Score and the calculation is based on Z-Score of threading alignment in LOMETS multiple-threading alignment and cluster density of I-TASSER simulation. TM and C Score were determined the structure similarity and confidence between the predicted protein model and the native protein structure (Barrett 1997). Ligand binding site also determined for binding the drug molecules to bind the cluster.

Extraction of secondary metabolites

The selected haloalkaliphilic actinomycete, Streptomyces spp. AJ8 was inoculated into starch casein broth and incubated at 28 °C on a shaker (200–250 rpm) for 7 days. The culture broth was filtered through 0.45 μm membrane filter (Millipore Millex-HV Hydrophilic PVDF) and the filtrate was extracted with ethyl acetate, chloroform and methanol (1:1v/v) and shaken vigorously for 1 h in a solvent extraction funnel. Solvent and filtrate mixture were stabilized for 24–48 h and separated from aqueous phase. The extracts were concentrated in a rotary evaporator and lyophilized (Al-Hulu et al. 2012).

Pharmacological influence of secondary metabolites

In vitro antibacterial and antifungal activity was performed by the secondary metabolites extracted from different solvents against pathogenic bacteria using agar diffusion following the method described by Holt et al. (1994). Antiviral activity was performed against White Spot Syndrome Virus (WSSV) following the method of Balasubramanian et al. (2006). The secondary metabolite incubated WSSV suspensions (29 °C for 3 h) were injected with intramuscularly to the Indian white shrimp, Fenneropenaeus indicus. Hemolymph was bled from the shrimps after the 3rd day of injection, and extracted the genomic DNA (Chang et al. 1999). Double step diagnostic PCR were performed from the genomic DNA template using the WSSV VP28 primer designed by Namita et al. (2007) and standard PCR protocols were followed (Takahashi et al. 1996). Anticancer activity was performed in L929 fibroblast cell lines treated with different concentrations (100, 500 and 1000 µg) of Streptomyces spp AJ8 yielded secondary metabolites and incubated for 24 h (Freshney 2006).

Data analysis

One way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was carried out using SPSS statistics data package. Means were compared at 0.001 % level.

Results

In vitro antagonistic activity

Among the different Streptomyces spp isolated from the haloalkaliphilic origin, the Streptomyces spp. AJ8 had the potent antagonistic activity against various bacterial and fungal pathogens. The antagonistic activity recorded of 21.1, 14.4, 12.4, 11.1, 11.5 and 9.8 mm of zone of inhibition against the bacterial pathogens, S. aureus, A. hydrophila WPD1, B. subtilis, E. coli and V. harveyi respectively. They also suppressed the fungal sp ranged between 9 to 11.5 mm of zone of inhibition (Table 1).

Table 1.

In vitro antagonistic activity of Streptomyces spp. AJ8 against bacterial and fungal pathogens

| Sl. no | Bacterial/fungal pathogens | Zone of inhibition (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Escherichia coli | 11.1 ± 1.0 |

| 2 | Staphylococcus aureus | 21.1 ± 0.6 |

| 3 | Bacillus subtilus | 12.4 ± 0.4 |

| 4 | Aeromonas hydrophila WPD1 | 14.4 ± 0.4 |

| 5 | Vibrio harveyi | 9.2 ± 0.4 |

| 6 | Aspergillus niger | 9.8 ± 0.3 |

| 7 | Candida albicans | 11.5 ± 0.2 |

| 8 | Pythium spp. | 8.1 ± 0.2 |

Phenotypic identification and cultural characteristics

The morphological, biochemical and physiological confirmative tests revealed that, the Streptomyces spp. AJ8 strain was Gram positive, non motile, MR positive, VP negative, negative for indole production and H2S production etc. They also ferment glucose, sucrose, mannitol, starch and sorbitol etc. Due to the haloalkaliphilic nature, the strain was able to grow well up to 8 % NaCl and 10.5 pH etc (Table 2). Macroscopic observations revealed that, they mostly grow well in starch casein agar, glycerol aspargin agar, nutrient agar, Knight’s agar, yeast extract malt extract agar, actinomycetes agar and tyrosin agar etc. The aerial, substrate mycelium and pigmentations were found brownish colours in all growth media (Table 3).

Table 2.

Biochemical and physiological characteristics of Streptomyces spp. AJ8 isolated from Kovalam solar salt works in comparison with reference Streptomyces strains

| Sl. no | Confirmative tests | AJ8a | Reference strains | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AJ9a | RJ1b | RJ2c | |||

| 1 | Grams staining | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | Motility | Non-motile | Non-motile | Motile | Motile |

| Biochemical tests | |||||

| 3 | Methyl Red (MR) | + | + | + | – |

| 4 | Voges Proskauer (VP) | – | – | – | – |

| 5 | Indole production | – | – | – | – |

| 6 | Nitrate reduction | + | + | + | + |

| 7 | TSI test | + | + | + | + |

| 8 | H2S production | – | – | – | – |

| 9 | Urease activity | – | – | – | – |

| 10 | Starch hydrolysis | + | – | + | – |

| Carbon source (1 % w/v) | |||||

| 11 | Glucose | + | + | + | + |

| 12 | Sucrose | + | + | + | + |

| 13 | Maltose | + | + | + | + |

| 14 | Mannitol | + | + | + | + |

| 15 | Starch | + | + | + | – |

| 16 | Sorbitol | + | + | + | – |

| Nitrogen sources (1 % w/v) | |||||

| 17 | Histidine | ++ | + | + | + |

| 18 | Valine | ++ | + | ++ | + |

| 19 | Alanine | ++ | + | + | + |

| 20 | Methionine | + | + | ++ | + |

| 21 | Tryptophan | + | + | + | + |

| Effect of pH | |||||

| 22 | 5.5 | + | + | + | + |

| 23 | 6.5 | + | + | + | + |

| 24 | 7.5 | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| 25 | 8.5 | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| 26 | 9.5 | +++ | + | – | – |

| 27 | 10.5 | + | – | – | – |

| Effect of NaCl concentration (w/v) | |||||

| 28 | 2 | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| 29 | 4 | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| 30 | 6 | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| 31 | 8 | ++++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| 32 | 10 | ++ | ++ | + | + |

Table 3.

Cultural and morphological characteristics of Streptomyces spp. AJ8 on different media

| Media | Culture characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth | Aerial mycelium | Substrate mycelium | Pigmentation | |

| Starch casein agar | Good | Ash | Dark brown | Brownish red |

| Glycerol Aspargin agar (ISP 5) | Moderate | Brown | Reddish brown | Brown |

| Nutrient agar | Good | Reddish brown | Light ash | Light brown |

| Knight’s agar | Abundant | Brown | Dark brown | Brownish red |

| Yeast extract malt extract agar (ISP2) | Fair | Brown | Light brown | Light brown |

| Actinomycetes isolation agar | Good | Brown | Reddish brown | Dark brown |

| Tyrosin agar (ISP 7) | Fair | Ash | Dark brown | Light brown |

Genomic identification

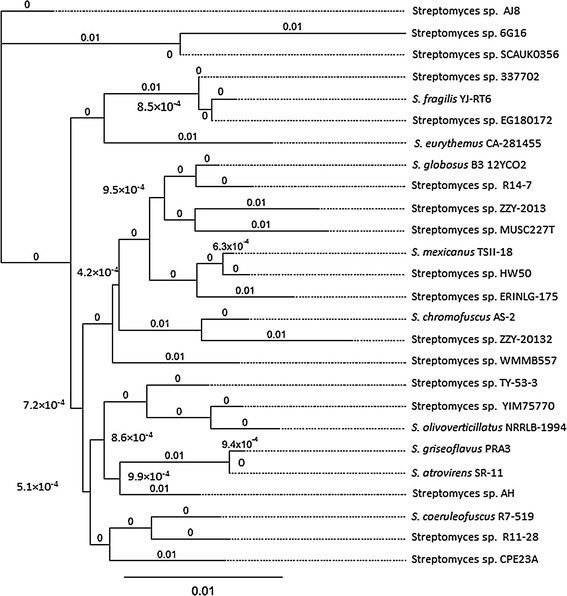

Phylogenetic and evolutionary analysis of the 16S rRNA sequence revealed that, Streptomyces spp. AJ8 shared high similarity to other Streptomyces spp strains including Streptomyces spp. 6G16, Streptomyces spp. SCAUKO356, Streptomyces spp. 337702, S. fragilis YJ-RT6 and Streptomyces spp. EG180172 (Fig. 1). The strain was deposited in NCBI database and the strain name and GenBank accession number are Streptomyces spp. AJ8, KC603899.1 respectively.

Fig. 1.

Graphical phylogenetic tree of halopalkaliphilic Streptomyces spp. AJ8 based on 16S rRNA gene sequence data compare with other Streptomyces spp. The tree was constructed using the HKY genetic distance model with neighbor-joining method

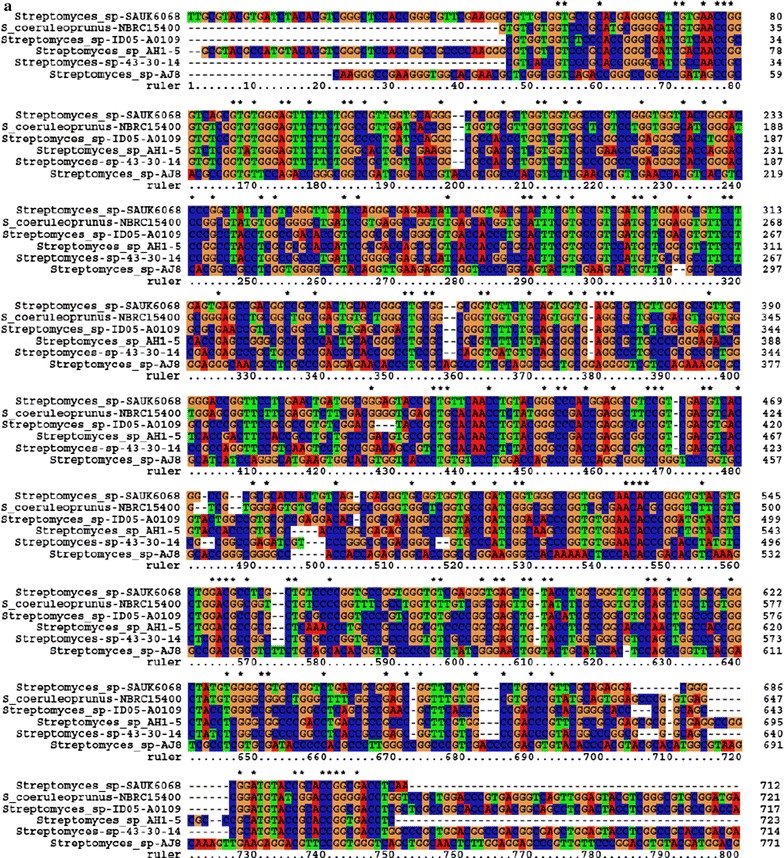

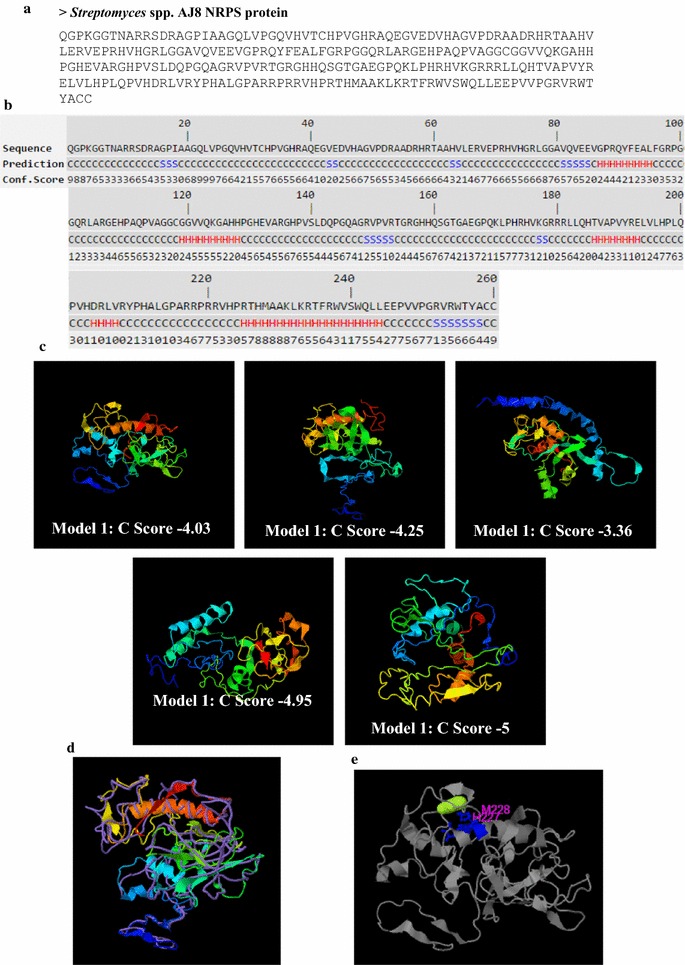

PCR amplification and sequencing of NRPS gene

The NRPS gene specific PCR amplification generated a single gene fragment of 781 bp length and submitted to NCBI database (GenBank: KR491940.1). Multiple sequence alignment analysis revealed that, the NRPS gene of Streptomyces spp. AJ8 was more identical to the other NRPS family in Streptomyces spp. SAUK6068, S. coeruleoprunus NBRC15400, Streptomyces spp. AH1-5 and Streptomyces spp. 43-30-14 (Fig. 2). Phylogenetic and evolutionary analysis of the NRPS gene sequence revealed that, Streptomyces spp. AJ8 shared more than 80 % similarity to other Streptomyces spp. including Streptomyces spp. 35-45-7, Streptomyces spp. SAUK6068, S. coeruleoprunus NBRC15400, Streptomyces spp. NBRC15387 and Kribella spp. ID05-A0415 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Nucleotide alignment identities of NRPS gene of haloalkaliphilic Streptomyces spp. AJ8 with its homologues. Asterisks indicate 100 % similarity among the nucleotide sequences

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of the nucleotide sequence of NRPS gene of haloalkaliphilic Streptomyces spp. AJ8 with that reported in other Streptomyces spp. by Neighbor Joining method using Geneious Pro analysis

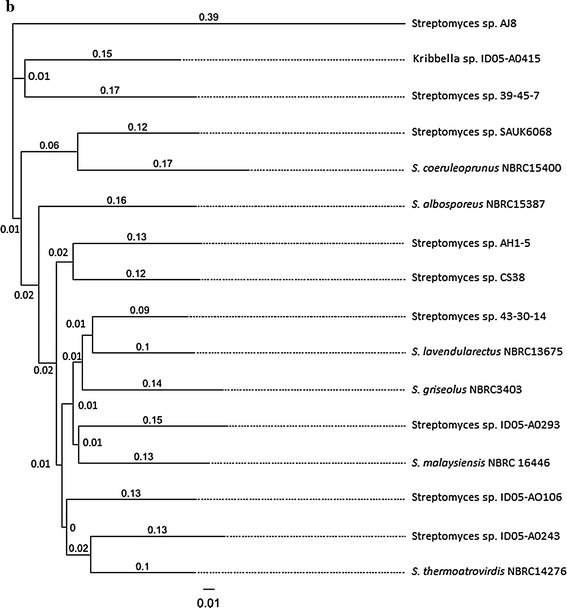

NRPS protein structure prediction analysis

The Fig. 4a, b shows the protein sequence and the predicted secondary structure of NRPS by I-TASSER analysis. The top five models predicted territory structure for NRPS protein by I-TASSER and the C-score were −4.03, −4.25, −3.36, −4095 and −3.36 respectively (Fig. 4c). The estimated TM-score and RMSD observed of 0.28 ± 0.09 and 15.8 ± 3.2 Å respectively. The TM-align structural alignment results revealed that, the top five PDB hits were 4nl6A, 1qonA, 2c3mB, 2fj0A and 1n35A and its TM scores were 0.843, 0.442, 0.432, 0.426 and 0.426 respectively. The five top most aligned proteins among the NRPS were spliceosome, acetylcholinesterase, ferredoxin oxidoreductases (PFOR), esterase and reovirus polymerase etc. (Fig. 4d). The multiple binding site ligands from different PDB hits (1zeiF, 2xmbA, 4ekdA, 3bz1H and 2hi8X) were confirmed as M-Cresol, Beta-l-Fucose, Cobalt (2+), Chlorophyll a and Bromide etc. (Fig. 4e; Table 4). The predicted EC numbers of the PDB hits were given in the Table 5. Based on the results revealed that, the five top most PDB enzyme hits were dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase Dcp, mouse acetylcholinesterase, Cys-418 thiylradical, human acetylcholinesterase and recombinant human butyrylcholinesterase.

Fig. 4.

a FASTA format of NRPS protein query sequence. b Secondary Structure Prediction of the NRPS protein of Streptomyces spp AJ8. (Color indications H Helix; S Strands and C Coil). c The predicted 3D model and the estimated global and local accuracy of the NRPS protein. d The structure alignment of NRPS between the first I-TASSER model and the top 5 most similar structure templates in PDB. e The predicted ligand-binding sites of the NRPS protein. (Fluorescent green yellow colour indicated the predicted ligand binding site)

Table 4.

Showing the ligand binding sites of the NRPS protein of Streptomyces spp AJ8

| Rank | C-score | Cluster size | PDB hit | Ligand name | Downloaded complex | Ligand binding site residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.05 | 3 | 1zeiF | CRS | Rep, Mult | 227, 228 |

| 2 | 0.05 | 3 | 2xmbA | FUL | Rep, Mult | 200, 203, 204, 212, 215 |

| 3 | 0.03 | 2 | 4ekdA | CO | Rep, Mult | 223, 227 |

| 4 | 0.02 | 1 | 3bz1H | CLA | Rep, Mult | 236, 239 |

| 5 | 0.02 | 1 | 2hi8X | BR | N/A | 86, 103, 104 |

Table 5.

The predicted enzyme commission numbers and active sites of the NRPS protein

| Rank | C-scoreEC | PDB hit | TM-score | RMSDEC | IDENEC | Cov | EC number | Active site residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.065 | 1y79A | 0.419 | 6.15 | 0.074 | 0.719 | 3.4.15.5 | NA |

| 2 | 0.065 | 1maaD | 0.404 | 6.29 | 0.048 | 0.704 | 3.1.1.7 | NA |

| 3 | 0.065 | 1h16A | 0.416 | 6.33 | 0.042 | 0.727 | 2.3.1.54 | NA |

| 4 | 0.065 | 1b41A | 0.345 | 6.35 | 0.030 | 0.623 | 3.1.1.7 | NA |

| 5 | 0.065 | 2pm8A | 0.406 | 6.39 | 0.046 | 0.727 | 3.1.1.8 | NA |

EC Enzyme commission

Pharmacological influence of secondary metabolites

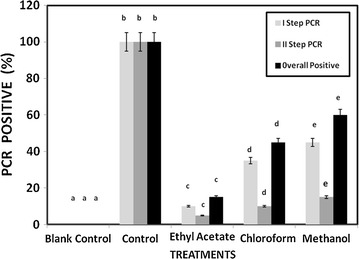

Among the different extractions the secondary metabolites which extracted from ethyl acetate were effectively suppressed the pathogenic bacteria of 19.2, 12.4, 10 mm of zone of inhibition in S. aureus, A. hydrophila WPD1 and E. coli respectively. The same metabolites also effectively suppressed the fungal growth the ranged between 8.5 and 10.3 mm of zone of inhibition against A. niger, C. albicans and Pythium spp. (Table 6). For antiviral activity, 100 % PCR positive signals were observed in the F. indicus when no secondary metabolites incubated WSSV injection given whereas the PCR signal was significantly (P < 0.001) reduced the secondary metabolites incubated WSSV injected shrimps. Among the secondary metabolites extracted from different solvents, ethyl acetate was effectively reduced the WSSV load by reflecting the week PCR signals after double step detection of only 15 %. The extraction also helps to reduce the WSSV load of 85 % from the control group (Fig. 5). Anticancer activity was performed in L929 fibroblast by treating with the secondary metabolites revealed that, the malformed cells seen in the cell culture after 24 h. After different concentration treated with the cancer cells, the secondary metabolites concentrations kill the L929 fibroblast cells at the rate of 75.23, 69.8 and 35.7 % in 100, 500 and 1000 µg/ml respectively and significantly (P < 0.001) differed (Table 7; Fig. 6).

Table 6.

Antimicrobial screening of Streptomyces spp AJ8 secondary metabolites against bacterial and fungal pathogens

| Microbial pathogens | Zone of inhibition (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethyl acetate | Chloroform | Methanol | |

| Escherichia coli | 10.0 ± 0.01 | 7.8 ± 0.01 | 6.1 ± 0.01 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 19.2 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 0.02 | 2.4 ± 0.4 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 5.4 ± 0.01 |

| Aeromonas hydrophila WPD1 | 12.4 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.04 | 5.09 ± 0.05 |

| Vibrio harveyi | 8.2 ± 0.05 | 4.09 ± 0.02 | 3.4 ± 0.4 |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus | 5.06 ± 0.04 | 3.2 ± 0.05 | 2.7 ± 0.03 |

| Aspergillus niger | 8.5 ± 0.5 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 5.2 ± 10 |

| Candida albicans | 10.3 ± 0.02 | – | – |

| Pythium spp. | 7.4 ± 0.9 | – | – |

Fig. 5.

Antiviral activity performed by F. indicus injected with WSSV incubated the secondary metabolites of Streptomyces spp AJ8. Antiviral activity determined by double step diagnostic PCR detection. Means with the same superscripts (a–e) do not differ from each other (P < 0.001): one way ANOVA

Table 7.

In vitro anticancer activity performed by MTT cell viability assay in L 929 cell lines by the applying Streptomyces spp AJ8 secondary metabolites

| Sl. no | Concentration (µg/ml) | OD (540 nm) | % viability |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Control | 0.630 | 100a |

| 2 | 100 | 0.474 | 75.23b |

| 3 | 500 | 0.440 | 69.8c |

| 4 | 1000 | 0.225 | 35.7d |

a–dMeans with the same superscript do not differ from each other (P < 0.001): one way ANOVA

Fig. 6.

In vitro anticancer activity performed by MTT cell viability assay in L929 cell lines by the applying Streptomyces spp AJ8 secondary metabolites extracted from ethyl acetate. Asterisk indicates malformed cells

Discussion

Haloalkaliphilic actinomycetes are a kind of extreme environment actinomycetes, which are highly tolerant to high NaCl concentration, as well as high pH which yielding to valuable industrial products including antimicrobials (Cai et al. 2009). Due to higher stability and tolerance of Streptomyces spp. AJ8 in extreme salinity and pH, their antimicrobial products are very effective against tested pathogens and they inhibit more than 10 mm of zone of inhibition. Streptomyces spp SBU1 isolated from the saltpan regions of Cuddalore, Tamilnadu, India showed most promising antagonistic activity against E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and S. aureus (Sudhakar et al. 2012). Moreover Aruljose et al. (2013) isolated and proved the antagonistic activity of polyketide producing halophilic Streptomyces spp. JAJ06 from the Tuticorin saltpan soils, India.

Halophilic actinomycetes including Streptomyces, Saccharopolyspora, Micromonospora, Nocardia, Nocardiopsis, and Nonomuraea were isolated identified from saltern ponds of Tuticorin, India (Aruljose and Jebakumar 2012). Interestingly some of the halophilic actinomycetes strains had showing optimum growth at 15 % NaCl was also found in salt lakes of Xinjiang, China (Cao et al. 2009). The present study the Streptomyces spp. AJ8 was well grown in the Knight’s agar media containing 10 % NaCl concentration. They also ferment glucose, sucrose, mannitol, starch and sorbitol etc. Two new species of Streptomonospora, named as Streptomonospora amylolytica and S. flavalba were isolated on starch-casein agar medium having 10 % NaCl (Cai et al. 2009). Our earlier study Streptomyces spp. AJ7, AJ9 and AJ10 which isolated from solar salt works were well grown in Starch casein agar, Tryptone yeast extract agar (ISP7) and Knight’s agar and produced the mycelium of light ash to white colour. They were also tolerated the pH of maximum 8.5 and grown well in 4 % NaCl (Jenifer et al. 2013).

The 16S rRNA sequencing has been widely used as a molecular clock to estimate relationships among the microbes, but more recently it has also become important as a means to identify unknown microbes up to the species level (Sacchi et al. 2002). In our study, 16S rRNA sequencing tools helped to identify the Streptomyces spp AJ8 and it was more than 90 % identical to other Streptomyces spp. including Streptomyces spp. 6G16, Streptomyces spp. SCAUKO356, Streptomyces spp 337702 and S. fragilis YJ-RT6. Sadeghi et al. (2014) isolated the salt tolerant Streptomyces spp. C-2012 from the Iranian soil, identified by taxonomic level using 16S rRNA gene sequencing and it revealed that, closely related to S. rimosus JCM 4667T. The sequence data for the 16S rRNA gene is highly conserved for different organisms and has also been shown to be very accurate for genus and species identification of bacteria and actinomycetes. Actinomycetes represent one of the most important sources for the discovery of new metabolites with biological activity; and many of these are described as being produced by polyketide synthases (PKS) and NRPS (Ayuso et al. 2005). In our study, the presence of NRPS gene cluster at the size of around 721 bp in the Streptomyces spp. AJ8, it may have potent antimicrobial and antitumor activities. The gene cluster involved the different pharmacological activities including antimicrobial, anti cancer and other activities proved by many authors. Mo et al. (2011) cloned and characterized a biosynthetic gene cluster, tirandamycin from marine-derived Streptomyces spp. SCSIO1666 with potential bacterial RNA polymerase inhibitory activity. Virginiamycin M (VM), a hybrid polyketide-peptide antibiotic had potent antibacterial activity was characterized from S. virginiae (Pulsawat et al. 2007). Arasu et al. (2012) also identified a polyketide metabolite had the antibacterial, antifungal and anticancer activities isolated from the marine Streptomyces spp. AP-123 isolated from Andra Pradesh, India. Moreover, the acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme binding site was observed in the NRPS gene. The AChE belongs to carboxylesterase family of enzymes that hydrolyzes the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. The AChE inhibitors were characterized from the compounds including arisugacins A and B which obtained from Penicillium sp. FO-4259 (Otogwo et al. 1997).

Our previous study by Jenifer et al. (2013) described that, Nocardiopsis spp. AJ1 and Streptomyces spp. AJ7 isolated from solar salt works had effectively controlled various aquatic and human pathogenic bacteria. Extremophilic actinomycetes are also considered as an unexplored source of antifungal compounds (Wu and Zhang 2007). In our studies, the ethyl acetate extracts were effectively suppressed the bacterial and fungal pathogens due to the antimicrobial compounds present in the metabolites. Due to the mid polarity of the ethyl acetate extraction, most of the polar and mid polar compounds active compounds eluted these solvents. A moderately halophilic Streptomyces spp. JAJ06 producing an antimicrobial compound of polyketide type was isolated from saltpan soil collected at Tuticorin, India (Aruljose et al. 2011). Antifungal secondary metabolites have been isolated from alkaliphilic N. dassonvillei WA52 (Ali et al. 2009), Nocardia spp. ALAA 2000 (El-Gendy et al. 2008) and marine Streptomyces spp. DPTB16 (Dhanasekaran et al. 2008). S. violaceusniger G10 produced antifungal metabolites that effectively inhibited the growth of Fusarium spp. (Getha and Vikineswary 2002). Antiviral activity of halotolerant actinomycetes is also reported against tobacco mosaic tobamovirus and potato Y potyvirus (Mohamed and Galal 2005). In our studies, ethyl acetate was effectively reduced the WSSV load by reflecting the week PCR signals after double step detection of only 15 %. The secondary metabolites of Streptomyces spp. AJ8 was inhibit the transcription and translation of the WSSV leading to arrest the viral multiplication. Serkedjieva et al. (2012) characterized a novel proteinaceous protease inhibitor from S. chromofuscus 34-1 (SS34-1) demonstrated a specific and selective anti-influenza virus effect. Furan-2-yl acetate, an antiviral compound extracted from marine Streptomyces sp VITSDK1 was effectively controlled the fish nodavirus (FNV) (Suthindhiran et al. 2009). The secondary metabolites concentrations kill the L929 fibroblast cells up to 35 % maximum in highest concentrations. The secondary metabolites from Streptomyces spp RJ8 expressed their highest anticancer activity (65 %) at 1000 µg/ml concentration against L 929 Fibroblast cell lines (Remya 2013). Pyrocoll, an antitumour compound was recently detected in novel alkaliphilic Streptomyces strain (Dietera et al. 2003). The moderately halophile Saccharopolyspora salina VITSDK4 produces an extracellular compound with cytotoxicity on HeLa cells that show the IC50 value of 26.2 µg/ml (Du et al. 2012). The secondary metabolites extracted from the Streptomyces spp. AJ8 had the potent antimicrobial and anticancer properties. The metabolites were highly influenced to control various pathogenic bacteria, fungi and the killer shrimp virus WSSV. The cluster gene NRPS was also successfully amplified from the genomic DNA of Streptomyces spp. AJ8 indicated that the NRPS gene responsible for the antimicrobial and anticancer activities. Further study need to sequencing the whole genome of the Streptomyces spp. AJ8 to find out the pharmacological important active compounds.

Authors’ contributions

JSCAJ played a major role for sample collection and overall experimental procedures of this study. MMB and SGVP participated in data analysis and drafting of the manuscript. TC involved in the design and organization of the study and interpreted the results. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Department of Science and Technology (DST), New Delhi, Government of India, for its financial support, in the form Research Project [DO NO. SR/SO/HS-0161/2012 dated 28.07.2014].

Compliance with ethical standards

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

John Selesteen Charles Adlin Jenifer, Email: adlinjenifer86@gmail.com.

Mariathason Birdilla Selva Donio, Email: mbirdilla@gmail.com.

Mariavincent Michaelbabu, Email: michaelmsu@live.com.

Samuel Gnana Prakash Vincent, Email: prakashvincent.icn@gmail.com.

Thavasimuthu Citarasu, Email: citarasu@msuniv.ac.in, Email: citarasu@gmail.com.

References

- Al-Hulu SM, Jarallah Alaa EM, Al-Charrakh AH. Extraction and partial purification of antimicrobial gent produced by Streptomyces spp. in Babylon province. J Babylon Univ Pure Appl Sci. 2012;22(1):279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Ali MI, Ahmad MS, Hozzein WN. WA 52—A Macrolide antibiotic produced by alkalophile Nocardiopsis dassonvilleli WA 52. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2009;3:607–616. [Google Scholar]

- Arasu VM, Asha KRT, Duraipandiyan V, Ignachimuthu V, Agastian P. Characterization and phylogenetic analysis on novel polyene type antimicrobial metabolite producing actinomycetes from marine sediments: Bay of Bengal India. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(10):803–810. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60233-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arif IA, Khan HA, Bahkali AH, Al Homaidan AA, Al Farhan AH, Al Sadoon M, Shobrak M. DNA marker technology for wildlife conservation. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2011;18:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruljose P, Jebakumar SRD. Phylogenetic diversity of actinomycetes cultured from coastal multipond solar saltern in Tuticorin, India. Aquat Biosyst. 2012;8:23. doi: 10.1186/2046-9063-8-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruljose P, Santhi VS, Jebakumar SRD. Phylogenetic affiliation, antimicrobial potential and PKS gene sequence analysis of moderately halophilic Streptomyces spp. inhabiting an Indian saltpan. J Basic Microbiol. 2011;51:348–356. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201000253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruljose P, Sivakala KK, Jebakumar SRD. Formulation and statistical optimization of culture medium for improved production of antimicrobial compound by Streptomyces spp. JAJ06. Int J Microbiol. 2013;526260:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2013/526260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayuso A, Clark D, González I, Salazar O, Anderson A, Genilloud O. A novel actinomycete strain de-replication approach based on the diversity of polyketide synthase and nonribosomal peptide synthetase biosynthetic pathways. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;67(6):795–806. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1828-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian G, Sarathi M, Rajesh Kumar S, Sahul Hameed AS. Screening the antiviral activity of Indian medicinal plants against white spot syndrome virus in shrimp. Aquaculture. 2006;263:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.09.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AJ. Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (NC-IUBMB). Enzyme nomenclature. Recommendations 1992. Supplement 4: corrections and additions. Eur J Biochem. 1997;250:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.0269a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Xue Q, Chen Z, Zhang R. Classification and Salt-tolerance of Actinomycetes in the Qinghai Lake Water and Lakeside Saline Soil. J Sustain Dev. 2009;2(1):107–110. doi: 10.5539/jsd.v2n1p107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L, Yun W, Tang S, Zhang P, Mao P, Jing X, Wang C, Lou K. Biodiversity and enzyme screening of actinomycetes from Hami Lake. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao. 2009;49(3):287–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CF, Su MS, Chen HY, Lo CF, Kou GH, Liao IC. Effect of dietary β 1,3-glucan on resistance to white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) in postlarval and juvenile Penaeus monodon. Dis Aquat Org. 1999;36:163–168. doi: 10.3354/dao036163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg GM, Newman DJ. Plants as source of anticancer agents. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;100:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanasekaran D, Thajuddin N, Panneerselvam A. An antifungal compound: 4′phenul-1-napthyl-phenyl acetamide from Streptomyces sp. DPTTB16. Facts Univ Med Biol. 2008;15:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietera A, Hamm A, Fiedler HP, Goodfellow M, Muller WE, Brun R, Bringmann G. Pyrocoll, an antibiotic, antiparasitic and antitumor compound produced by a novel alkaliphilic Streptomyces strain. J Antibiot. 2003;56(7):639–646. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.56.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L, Sänchez C, Chen M, Edwards DJ, Shen B. The biosynthetic gene cluster for the antitumor drug bleomycin from Streptomyces verticillus ATCC15003 supporting functional interactions between nonribosomal peptide synthetases and a polyketide synthase. Chem Biol. 2012;7:623–642. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(00)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Gendy MMA, Hawas UW, Jaspars M. Novel bioactive metabolites from a marine derived bacterium Nocardia sp. ALAA 2000. J Antibiot. 2008;61:379–386. doi: 10.1038/ja.2008.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fencial W. New pharmaceuticals from marine organisms. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15:339–341. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freshney RI. Culture of animal cells: a manual of basic technique. 5. New Jersey: Wiley Liss Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Getha K, Vikineswary S. Antagonistic effects of Streptomyces violaceusniger strain G10 on Fusarium oxysporum sp. cubense race 4: indirect evidence for the role of antibiosis in the antagonistic process. J Indian Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;28:303–310. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.7000247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt JG, Krieg NR, Sheath PHA, Staley JT, Williams ST. Bergey’s Manual of determinative bacteriology. 9. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Horikoshi K (1991) General view of alkaliphiles and thermophiles. In: Horikoshi K, Grant WD (eds) Superbugs: Micro-organisms in Extreme Environments. Springer, Berlin, pp 3–13

- Jenifer JA, Donio MBS, Thangaviji V, Velmurugan S, Michaelbabu M, Albindhas S, Citarasu T. Halo-alkaliphilic actinomycetes from solar salt works in India: diversity and antimicrobial activity. Blue Biotechnol J. 2013;2(1):137–151. [Google Scholar]

- Lam KS. Discovery of novel metabolites from marine actinomycetes. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:341–351. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manivasagan P, Venkatesan J, Sivakumar K, Kima S. Marine actinobacterial metabolites: current status and future perspectives. Microbiol Res. 2013;168:311–332. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo X, Wanga Z, Wang B, Ma J, Huang H, Tian X, Zhang S, Zhang C, Ju J. Cloning and characterization of the biosynthetic gene cluster of the bacterial RNA polymerase inhibitor tirandamycin from marine-derived Streptomyces spp. SCSIO1666. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;406:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed SH, Galal AM. Identification and antiviral activities of some halotolerant Streptomyces isolated from Qaroon Lake. Int J Agric Biol. 2005;7(5):747–753. [Google Scholar]

- Mootz HD, Marahiel MA. Biosynthetic systems for nonribosomal peptide antibiotic assembly. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1997;1:543–551. doi: 10.1016/S1367-5931(97)80051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namita R, Kumar S, Jaganmohan S, Murugan V. DNA vaccines encoding viral envelope proteins confer protective immunity against WSSV in black tiger shrimp. Vaccine. 2007;25:2778–2786. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otogwo K, Kuno F, Omura S. Arisugacins, selective Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors of microbial origin. Pharmacol Ther. 1997;76(1–3):45–54. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7258(97)00093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulsawat N, Kitani S, Nihira T (2007) Characterization of biosynthetic gene cluster for the production of virginiamycin M, a streptogramin type A antibiotic, in Streptomyces virginiae. Gene 15: 393(1-2): 31-42 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Remya R (2013) Screening and characterization of biosurfactants from haloalkaliphilic actinomycetes isolated from solar salt works in Kanyakumari district. M. Phil dissertation submitted to Manonmaniam Sundaranar university, Tamilnadu, India

- Remya M, Vijayakumar R. Isolation and characterization of marine antagonistic actinomycetes from west coast of India. Facta Univ Ser Med Biol. 2008;15(1):13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Roongsawang N, Lim SP, Washio K, Takano K, Kanaya S, Morikawa M. Phylogenetic analysis of condensation domains in the nonribosomal peptide synthetases. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;252:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:725–738. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacchi CT, Whitney AM, Mayer LW, Morey R, Steigerwalt A. Sequencing of 16S rRNA Gene: a Rapid Tool for Identification of Bacillus anthracis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;10:1117–1123. doi: 10.3201/eid0810.020391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi A, Soltani BM, Jouzani GS, Karimi E. Taxonomic study of a salt tolerant Streptomyces sp. strain C-2012 and the effect of salt and ectoine on lon expression level. Microbiol Res. 2014;169:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer D, Finking R, Marahiel MA. Nonribosomal peptides: from genes to products. Nat Prod Rep. 2003;20:275–287. doi: 10.1039/b111145k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serkedjieva J, Dalgalarrondo M, Angelova-Duleva L, Ivanova I. Antiviral potential of a proteolytic inhibitor from Streptomyces chromofuscus 34-1. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2012;26(1):2786–2793. doi: 10.5504/BBEQ.2011.0097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M, Nakagawa Y, Sato Y, Furumai T, Igarashi Y, Onaka H, Yoshida R, Kunoh H. Studies on endophytic actinomycetes (I) Streptomyces spp. Isolated from Rhododendron and its antifungal activity. J Gen Plant Pathol. 2000;66:360–366. doi: 10.1007/PL00012978. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shirling EB, Gottlieb D. Methods for characterization of Streptomyces species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1966;16:313–340. doi: 10.1099/00207713-16-3-313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shomurat T, Yoshida J, Amano S, Kojima M, Inouye S, Niida T. Studies on actinomycetales producing antibiotics only on agar culture I. Screening taxonomy and morphology-productivity relationship of Streptomyces halstedii, strain SF-1993. J Antibiot. 1979;32:427–435. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.32.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneath PHA, Sokal RR. Numerical taxonomy. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Sudhakar T, Krishnakumar S, Premkumar J, Rani R. Characterization of halophilic antagonistic Actinomycetes isolated from solar saltpan of Tamilnadu, India. Int J Res Rev Pharm Appl Sci. 2012;2(4):793–802. [Google Scholar]

- Suthindhiran K, Sarath babu V, Ishaq Ahmed VP, Sahul Hameed AS, Kannabiran K. In vitro antiviral activity of furan-2-yl acetate extracted from marine derived Streptomyces spp. against fish nodavirus. New Biotechnol. 2009;25:S82. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2009.06.342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Itami T, Maeda M, Suzuki N, Kasornchandra J, Supamattaya K, Khongpradit R, Boonyaratpalin S, Kondo M, Kawai K, Kusuda R, Hirono I, Aoki T. Polymerase chaln reaction (PCR) amplification of bacilllform virus (RVPJ) DNA in Penaeus japonicus Bate and systemic ectodermal and mesodermal baculovirus (SEMBV) DNA in Penaeus monodon Fabricus. J Fish Dis. 1996;19:399–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.1996.tb00379.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasavada S, Thumar J, Singh SP. Secretion of a potent antibiotic by salt-tolerant and alkaliphilic actinomycete Streptomyces sannanensis strain RJT-1. Curr Sci. 2006;91(10):1393–1397. [Google Scholar]

- Vinothini G, Murugan M, Sivakumar K, Sudha S. Optimization of protease production by an actinomycete strain, PS-18A isolated from an estuarine shrimp pond. Afr J Biotechnol. 2008;18:3225–3230. [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Zhang Y. LOMETS: a local meta-threading-server for protein structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3375–3382. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafrilla B, Martínez-Espinosa RM, Alonso MA, Bonete MJ. Biodiversity of Archaea and floral of two inland saltern ecosystems in the Alto Vinalopó Valley, Spain. Saline Syst. 2010;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1746-1448-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]